History of surgery facts for kids

Surgery is a special part of medicine where doctors use their hands and tools to fix problems inside the body. It helps to find, stop, or cure illnesses. A famous French surgeon named Ambroise Paré once said that surgery is about taking out what's extra, putting back what's moved, separating what's stuck together, joining what's split apart, and fixing nature's mistakes.

People have been using tools for surgery for a very long time. They kept finding better ways to do it. But for many centuries, surgeons faced three big challenges: lots of bleeding, terrible pain, and dangerous infections. After the Industrial Revolution, new discoveries helped overcome these problems. This changed surgery from a risky "art" into a scientific field that can treat many diseases and conditions safely.

Contents

- How Surgery Began

- Ancient Times

- Middle Ages: Learning and Barber-Surgeons

- Early Modern Europe: New Ways of Learning

- Modern Surgery: Science and Safety

- Key Moments in Surgery History

- Important People in Surgery History

- See also

How Surgery Began

The first surgical methods were used to treat injuries. Old discoveries and studies of ancient groups show early ways to stitch cuts, remove badly damaged body parts, and clean or seal open wounds. For example, some Asian tribes used a mix of saltpeter and sulfur to burn and seal wounds. The Dakota people used a feather quill and an animal bladder to suck out pus. Stone Age needles suggest they were used for stitching. The Maasai used acacia needles for the same thing. Tribes in India and South America even used termites or scarabs to bite wound edges, then twisted their necks to leave the heads attached like staples!

Ancient Brain Surgery: Trepanation

The oldest known operation is called trepanation. This is when a hole is drilled or scraped into the skull. It was done to help with head injuries or other brain problems. Doctors would look at the wound and remove bone pieces. They also had ways to prevent infection and help healing.

Evidence of trepanation has been found in very old human remains from about 6500 BCE. Some cave paintings also show it. It was even described by ancient Greek writers like Hippocrates. In one old burial site in France, 40 out of 120 skulls from 6500 BCE had trepanation holes. Some experts believe it was done to cure epileptic seizures, bad migraines, and certain mental disorders.

Many people who had this surgery actually survived! Their skull bones show signs of healing. In some studies, more than half of the people lived through the operation.

Removing Body Parts: Amputation

The oldest known surgical amputation happened in Borneo about 31,000 years ago. A person had the lower part of their left leg removed. They survived and lived for another 6 to 9 years! This is the only known amputation before farming became common. The next oldest was about 7000 years ago in France, where a farmer had their left forearm surgically removed.

Fixing Broken Bones

Archaeologists have found ancient human bones with healed fractures. This suggests that people in prehistoric times knew how to set and splint broken bones.

The Aztecs also had ways to treat broken bones. Spanish writings from the conquest of Mexico say that if a broken bone wasn't fixed by splinting, they would make a cut at the end of the bone. Then, they would insert a branch of fir into the bone's middle part. Modern medicine developed a similar technique in the 20th century called medullary fixation.

Controlling Pain: Anesthesia

For a long time, surgery was incredibly painful. Finding ways to stop pain was a huge step forward.

Bloodletting: An Old Practice

Bloodletting is one of the oldest medical practices. It was used by many ancient groups, including the Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Greeks, Mayans, Indians, and Aztecs. In ancient Greece, doctors like Erasistratus thought many diseases were caused by too much blood. They suggested treating this with exercise, sweating, less food, and vomiting.

Later, bloodletting became very popular in the West. During the Renaissance, people even had calendars that showed the best times to let blood. Books claimed it could cure inflammation, infections, strokes, and even some mental disorders.

Ancient Times

Mesopotamia: Gods and Doctors

The Sumerians believed that sickness was a punishment from demons if someone broke a rule. So, doctors had to learn about 6,000 possible demons! They used methods like watching birds, stars, and animal livers to figure things out. This meant medicine was closely tied to priests, and surgery was seen as less important.

Still, the Sumerians developed important medical tools. In Ninevah, archaeologists found bronze tools that look like modern scalpels, knives, and drills for the skull. The Code of Hammurabi, an early set of laws from Babylon, even had rules for surgeons. It talked about how much doctors should be paid and what would happen if they made mistakes. For example, if a doctor saved an eye, they got paid. But if they caused harm, their hands could be cut off!

Ancient Egypt: Imhotep and Papyrus Scrolls

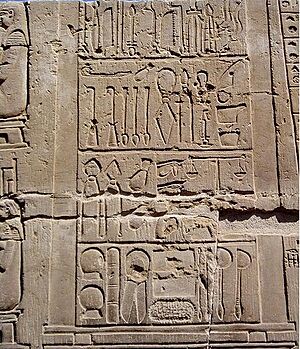

Around 3100 BCE, Egyptian civilization grew strong. Narmer, the first Pharaoh, made Memphis his capital. Like the Sumerians, the Egyptians wrote down their knowledge using hieroglyphics.

The first book on surgery was written around 2700 BCE by Imhotep. He was a very important person: Pharaoh Djoser's advisor, a priest, astronomer, and doctor. He was so famous for his medical skills that he became the Egyptian god of medicine!

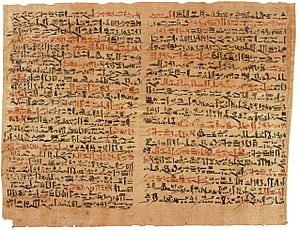

One of the most important discoveries about ancient Egyptian medicine is the Ebers Papyrus. This long scroll, found by Georg Ebers, is one of the oldest medical texts. It's from about 1550 BCE and is 20 meters long! It has recipes, medicines, and descriptions of many diseases and beauty treatments. It even tells how to treat crocodile bites and severe burns. It suggests draining pus from infections but warns against touching certain diseased skin.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is another old scroll, from about 1600 BCE. It's a guide for treating injuries and describes 48 different cases. It explains how to fix a broken nose and use stitches to close wounds. Infections were treated with honey. For example, it gives steps for a dislocated spine:

You should bind it with fresh meat the first day. You should loosen his bandages and apply grease to his head as far as his neck, (and) you should bind it with ymrw. You should treat it afterwards with honey every day, (and) his relief is sitting until he recovers.

India: Early Dental and Plastic Surgery

Mehrgarh: Ancient Dentistry

Teeth found in a very old graveyard in Mehrgarh show signs of drilling. This means people in prehistoric times might have tried to cure toothaches using drills made from flint heads.

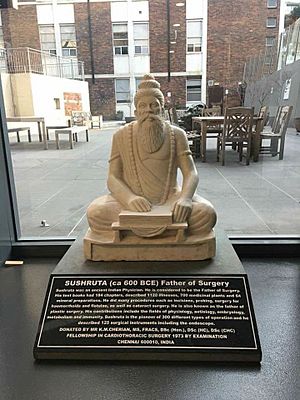

Ayurveda: Sushruta, Father of Surgery

Sushruta (around 600 BCE) is often called the "founding father of surgery." He lived and taught surgery near the Ganges River in Varanasi in Northern India. Much of what we know about him comes from his writings in Sanskrit, called the Sushruta Samhita. This is one of the oldest surgical texts. It describes how to examine, diagnose, treat, and predict the outcome of many illnesses. It also includes detailed procedures for plastic surgery, especially rhinoplasty (nose surgery).

Greece and the Hellenized World

In ancient Greece, doctors were expected to use their hands to do all medical tasks, including treating battlefield wounds and fixing broken bones. This was called χειρουργείν (cheirourgein), which means "working with the hands."

The famous Greek poet Homer wrote about two doctors, Podaleirius and Machaon, in The Iliad. They were sons of Asklepios, the god of medicine.

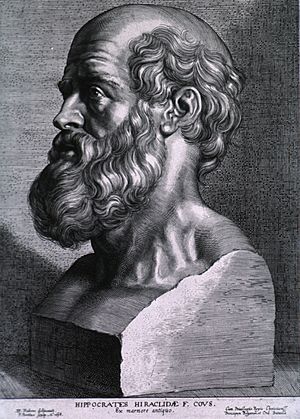

Hippocrates: The Oath and Medical Ethics

The Hippocratic Oath, written in the 5th century BC, set the first rules for how doctors should act. It covered professional behavior and how to treat patients with care and privacy. The many writings of the Hippocratic corpus helped separate proper medical practice from folk medicine, which often involved superstitions. These writings included books on joints, fractures, head injuries, ulcers, and hemorrhoids.

Celsus and Alexandria: New Discoveries

Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos were two important doctors in Alexandria. They helped start the scientific study of how the body works. Surgeons in Alexandria made progress in tying off blood vessels (hemostasis), removing bladder stones (lithotomy), hernia operations, eye surgery, and plastic surgery. They also found ways to fix dislocations and fractures, and even used mandrake as a painkiller. Most of what we know about them comes from Celsus and Galen.

Galen: Experiments and Ligatures

Galen was a very skilled Greek surgeon and doctor in the 2nd century Roman era. He performed complex operations and greatly added to our knowledge of how human and animal bodies work. He was one of the first to use ligatures (tying off blood vessels) in his experiments. Galen is also known as "The king of the catgut suture" because he used catgut for stitches.

China: Anesthesia and Heart Concepts

In China, tools that look like surgical instruments have been found from the Bronze Age. These were used along with herbs for healing.

Hua Tuo: First Anesthesia

Hua Tuo (140–208) was a famous Chinese doctor during the Eastern Han and Three Kingdoms era. He was the first person known to perform surgery using anesthesia. This was about 1600 years before it was used in Europe! Another doctor, Bian Que, was called a "miracle doctor." Some stories even say he performed a heart exchange between people, using general anesthesia. While this story might not be entirely true, it shows that the idea of heart transplantation existed in China around 300 CE.

Middle Ages: Learning and Barber-Surgeons

During the Middle Ages, important medical texts were written and translated. Paul of Aegina's Pragmateia was very influential. Later, Abulcasis from the Islamic Golden Age repeated much of this information.

Many Arab and Persian doctors made big contributions. Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873) translated many Greek medical texts and wrote the first detailed book on ophthalmology (eye care). Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (c. 865–925) helped develop experimental medicine and founded pediatrics (children's medicine). Avicenna (980–1037) wrote The Canon of Medicine, which combined Greek and Arab medicine and was used in Europe for centuries.

In the 9th century, the Medical School of Salerno in Italy became famous, using Arabic texts. Universities like Montpellier, Padua, and Bologna also became known for medicine.

Abulcasis (936–1013) was a great medieval surgeon from Spain. His books on surgery were very important.

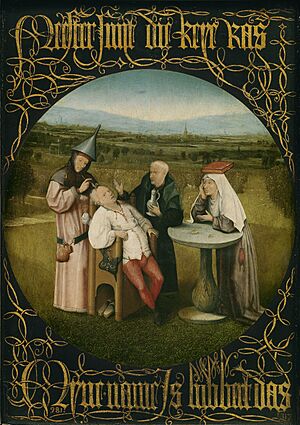

In the 13th century in Europe, skilled workers called barber-surgeons performed operations like amputations and setting broken bones. They had less status than university-trained doctors. They often had little formal training and a poor reputation. This didn't change until academic surgery became a respected medical field in the 18th century.

Guy de Chauliac (1298–1368) was one of the most important surgeons of the Middle Ages. His book Chirurgia Magna (Great Surgery) was a standard text for surgeons for a long time.

Early Modern Europe: New Ways of Learning

This period saw some important steps forward in surgery. Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), a professor of anatomy, changed how people learned about the body. Instead of just reading old texts, he pushed for "hands-on" dissection. His book De humani corporis fabrica showed many mistakes in older anatomy books and said that all surgeons should learn by dissecting bodies themselves.

Another key person was Ambroise Paré (c. 1510 – 1590), a French army surgeon. Before him, doctors used boiling oil to seal gunshot wounds, which was incredibly painful and dangerous. Paré started using a gentler mix of egg yolk, rose oil, and turpentine. He also found better ways to tie off blood vessels during an amputation.

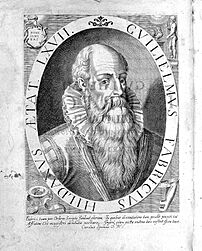

Wilhelm Fabry (1540–1634), known as "the Father of German Surgery," was the first to suggest amputating above the infected area. His wife and assistant, Marie Colinet (1560–1640), improved techniques for Caesarean Sections. In 1624, she was the first to use a magnet to remove metal from a patient's eye.

Modern Surgery: Science and Safety

Scientific Surgery Begins

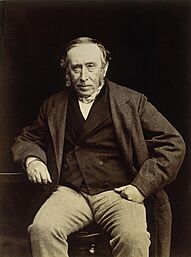

Surgery became a true science during the Age of Enlightenment (1715–90). A very important person was John Hunter (1728–1793), a Scottish surgeon in London. He is often called the father of modern scientific surgery. He brought a scientific, experimental way of thinking to surgery. Hunter didn't just trust old ideas; he did his own experiments to find the truth. He collected over 13,000 body specimens, from plants and animals to humans, to compare and learn from.

Hunter introduced many new surgical methods. These included ways to fix damage to the Achilles tendon and a better way to tie off arteries for an aneurysm. He also understood how important pathology (studying diseases) was. He saw the danger of infection spreading and how inflammation and bone problems could ruin a surgery's success. Because of this, he believed surgery should only be used as a last resort.

Hunter's student, Benjamin Bell (1749–1806), became the first scientific surgeon in Scotland. He suggested using opium to help patients recover after surgery. He also advised surgeons to "save skin" to help wounds heal faster.

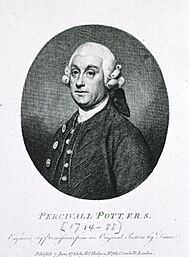

Other important surgeons from the 18th and early 19th centuries include Percival Pott (1714–1788). He first described tuberculosis of the spine. He also showed that cancer could be caused by something in the environment. He noticed that chimney sweeps often got scrotal cancer because of soot. Astley Paston Cooper (1768–1841) was the first to successfully tie off the main artery in the abdomen. James Syme (1799–1870) invented a new type of amputation for the ankle joint. The Dutch surgeon Antonius Mathijsen invented the Plaster of Paris cast in 1851.

Anesthesia: Making Surgery Painless

Starting in the 1840s, surgery changed a lot with the discovery of effective painkillers like ether and chloroform. Ether was first used by American surgeon Crawford Long (1815–1878). Chloroform was discovered by James Young Simpson (1811–1870) and later used by John Snow (1813–1858), who was Queen Victoria's doctor. In 1853, he gave chloroform to Queen Victoria during childbirth.

Anesthesia not only stopped patient suffering but also allowed doctors to perform more complicated operations inside the body. The discovery of muscle relaxants like curare also made surgeries safer. American surgeon J. Marion Sims (1813–83) is known for helping to create gynecology (women's health surgery).

Antiseptic Surgery: Fighting Infection

When anesthesia made more surgeries possible, it also led to more dangerous infections after operations. For a long time, people in Europe didn't understand how infections spread. They thought bad air caused infections in wounds.

The first step in fighting infection in Europe was made in 1847 by Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis. He noticed that medical students who came from dissecting dead bodies were causing more deaths among mothers giving birth compared to midwives. Semmelweis, despite being laughed at, made everyone wash their hands before entering the maternity wards. This led to a big drop in deaths, but his advice was ignored by many.

It wasn't until the work of British surgeon Joseph Lister in the 1860s that big progress was made. Lister learned about the work of French chemist Louis Pasteur. Pasteur showed that tiny living things (micro-organisms) could cause rotting and fermentation. Pasteur suggested three ways to get rid of these micro-organisms: filtering, heating, or using chemical solutions.

Lister used Pasteur's ideas to develop antiseptic techniques for wounds. Since heating or filtering wasn't good for human tissue, Lister tried spraying carbolic acid on his instruments. He found that this greatly reduced a serious infection called gangrene. He published his findings, and his work was groundbreaking. It quickly led to modern antiseptic operating rooms being used everywhere within 50 years.

Lister kept working on better ways to prevent infection. He realized it was best to stop bacteria from getting into wounds in the first place. This led to the idea of sterile surgery. Lister told surgeons to wear clean gloves and wash their hands in a carbolic solution before and after operations. He also introduced the steam sterilizer to make equipment completely clean. His discoveries changed surgery forever, and he is often called the father of modern surgery. These three big steps – a scientific approach, anesthesia, and sterile equipment – created the foundation for today's advanced surgery.

In the late 19th century, William Stewart Halstead (1852–1922) set down basic rules for keeping things sterile, known as Halsteads principles. He also introduced the latex medical glove. He designed rubber gloves that could be dipped in carbolic acid after one of his nurses got skin damage from sterilizing her hands.

X-rays: Seeing Inside the Body

The use of X-rays became a very important tool for doctors after their discovery in 1895 by German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen. He found that these rays could pass through skin. This allowed doctors to see the bones inside the body on a special photographic plate.

Modern Technologies in Surgery

Over the last century, many new technologies have greatly changed surgery. These include Electrosurgery in the early 1900s, practical Endoscopy starting in the 1960s, and Laser surgery, Computer-assisted surgery, and Robotic surgery, which were developed in the 1980s. These tools allow surgeons to perform operations with incredible precision and less invasion.

Key Moments in Surgery History

- 31,000 years ago: The first known amputation. The person lived for many years after.

- 5000 BCE: Early evidence of Trepanation (skull surgery) in France.

- 3300 BCE: Trepanation, broken bone treatments, and wound care in the Indus Valley civilization.

- 1754 BCE: The Code of Hammurabi includes laws about surgeons.

- 1600 BCE: The Edwin Smith Papyrus from Egypt describes 48 cases of injuries and treatments, including stitches and using honey for infections.

- 1550 BCE: The Ebers Papyrus from Egypt lists over 800 medicines and treatments.

- 600 BCE: Sushruta of India, known as the "founding father of surgery."

- 400 BCE: Hippocrates of Cos, "the Founder of Western Medicine," emphasizes scientific methods and cleanliness in surgery.

- 200 CE: Galen pioneers the use of ligatures (tying off blood vessels) in experiments.

- 208 CE: Hua Tuo in China uses wine as an anesthetic for surgery.

- 1162: The Council of Tours bans surgery for breast cancers.

- 1214: Hugh of Lucca discovers that wine can clean wounds.

- 1536: Ambroise Pare finds that cold bandages are better than hot oil for wounds.

- 1543: Andreas Vesalius publishes The Fabric of the Human Body, changing anatomy studies.

- 1735: Claudius Amyand performs the first successful appendectomy.

- 1776: John Hunter pioneers artificial insemination.

- 1842: Crawford Williamson Long pioneers ether for anesthesia.

- 1848: James Young Simpson pioneers chloroform for anesthesia.

- 1851: Antonius Mathijsen invents the Plaster of paris cast.

- 1860s: Joseph Lister introduces antiseptic surgery, greatly reducing infections.

- 1895: Wilhelm Röntgen discovers X-rays, allowing doctors to see inside the body.

- 1901: Karl Landsteiner discovers the basic A-B-AB-O blood types.

- 1914: Blood transfusion is pioneered.

- 1925: The first open heart surgery by English surgeon Henry Souttar.

- 1954: The first successful kidney transplant.

- 1962: The first successful hip replacement surgery.

- 1967: The first successful heart transplant by Christiaan Barnard.

- 1972: The CT scan is perfected.

- 1983: Robot-assisted surgery begins.

- 2000: The da Vinci Surgical System (a robotic surgery system) is approved.

- 2001: The first remote surgery is performed using a robot.

- 2005: The first partial face transplant.

- 2012: The first successful mother-daughter womb transplant.

- 2013: The first virtual surgery using Google Glass.

Important People in Surgery History

- Sushruta (1200–600 BCE)

- Theodoric Borgognoni (1205–1296)

- Guy de Chauliac (c.1300–1368)

- Ambroise Pare (1510–1590)

- William Cheselden (1688–1752)

- Percivall Pott (1714–1789)

- John Hunter (1728–1793)

- Astley Cooper (1768–1843)

- James Marion Sims (1813–1883)

- Joseph Lister (1827–1912)

- Erich Mühe (1938–2005)

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la cirugía para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la cirugía para niños

- History of anatomy

- History of medicine

- Timeline of medicine and medical technology

- History of trauma and orthopaedics

- American Board of Surgery

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |