History of the Cherokee language facts for kids

This article tells the story of the Cherokee language, a special language spoken by the Cherokee people. It's an Iroquoian language, meaning it's part of a family of languages spoken by many Native American groups. In 2019, the leaders of the Cherokee tribes announced that the language was in danger of disappearing. They called for more programs to help bring it back to life.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The Cherokee people call their language Tsalagi (ᏣᎳᎩ) or Tslagi. They call themselves Aniyunwiya (ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ), which means "Principal People." The Iroquois people in New York used to call the Cherokee Oyata’ge’ronoñ, meaning "inhabitants of the cave country."

There are many ideas about where the name "Cherokee" came from, but none are fully proven. One idea is that it came from the Choctaw word Cha-la-kee, meaning "those who live in the mountains." Another Choctaw word, Chi-luk-ik-bi, means "those who live in the cave country." The first time the Spanish wrote down the name in 1755, it was Tchalaquei.

Another idea is that "Cherokee" came from a Lower Creek word, Cvlakke, which means someone who speaks a different language. In the old Lower dialect of ᏣᎳᎩ, spoken in what is now Georgia and South Carolina, the Cherokee called their language jaragi. This dialect had a rolling "r" sound instead of the "l" sound found in other dialects. This might be how the English name for the people came to be.

A researcher named James Mooney studied the origin of "Cherokee" in the 1800s. In his book Myths of the Cherokee (1888), he wrote that the name first appeared as Chalaque in a Portuguese story from 1557. Later, it was Cheraqui in a French paper in 1699, and "Cherokee" in English by 1708. This shows the name has been around for a long time!

Early Cherokee History

There are two main ideas about where the Cherokee people originally came from. Most of what we know about their early history comes from their traditional language.

Where Did They Come From?

One idea is that the Cherokee, who speak an Iroquoian language, arrived in the Southern Appalachia more recently. They might have moved south from northern areas, where other Iroquoian-speaking groups lived, like the Haudenosaunee (Five Nations). In the 1800s, researchers talked to older Cherokee people who shared stories about their ancestors moving south from the Great Lakes area a long, long time ago.

The other idea, which some experts disagree with, is that the Cherokee have been in the Southeast for thousands of years. Before Europeans arrived, the Cherokee were part of a group called the Pisgah phase in Southern Appalachia, which lasted from about 1000 to 1500 AD.

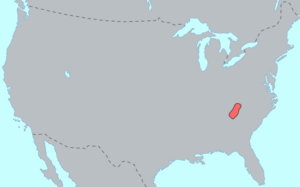

In 1540, the Cherokee claimed a huge area of land – about 40,000 square miles – in what is now the southeastern United States. This included parts of Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Old Cherokee Society

Much of what we know about Cherokee culture before the 1800s comes from the writings of an American writer named John Howard Payne. His papers describe how Cherokee elders talked about an old way of organizing their society. There was a "white" group of elders who represented the seven clans. This group was passed down through families and was in charge of religious activities like healing, cleaning, and praying.

There was also a "red" group of younger men who were responsible for warfare. Fighting was seen as something that made people "unclean," so the religious leaders had to purify the warriors before they could return to normal village life. This old system had disappeared long before the 1700s. People have wondered why it changed, with some saying it was because the Cherokee rebelled against the religious leaders, known as the Ani-kutani.

Cultural researcher James Mooney, who studied the Cherokee in the late 1800s, believed this rebellion led to the decline of the old system. By Mooney's time, Cherokee religious practices were more informal, based on what individuals knew and could do, rather than on family lines.

Another important source of early cultural history comes from writings by didanvwisgi (Cherokee: ᏗᏓᏅᏫᏍᎩ), who were Cherokee medicine men. They wrote these materials in the 1800s after Sequoyah created the Cherokee syllabary in the 1820s. At first, only the didanvwisgi used these writings, which were thought to be very powerful. Later, the Cherokee people widely adopted the writing system.

Unlike most other Native Americans in the American southeast long ago, the Cherokee spoke an Iroquoian language. Since the Great Lakes region was where most Iroquoian languages were spoken, experts think the Cherokee might have moved south from that area. However, some argue that the Iroquois moved north from the southeast, with the Tuscarora separating from them during the journey.

Studying the languages shows a big difference between Cherokee and the northern Iroquoian languages. This suggests they split a very long time ago. Studies of language change suggest this split happened between about 1,500 and 1,800 BC. The ancient village of Kituwa on the Tuckasegee River, now part of Qualla Boundary (the reservation of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians), is often called the original Cherokee settlement in the Southeast.

Contact with Europeans

17th Century: English Arrive

In 1657, there was some trouble in the Virginia Colony when a group called the Rechahecrians or Rickahockans, along with the Siouan Manahoac and Nahyssan, moved into the area near what is now Richmond, Virginia. The next year, English settlers and the Pamunkey people worked together to drive them away. Historians have debated who the Rechahecrians were, with some thinking they might have been parts of the Erie tribe who were forced out of the Lake Erie area by the powerful Iroquois in 1654. However, few historians believe this tribe was Cherokee.

Virginian traders started a small trading system with the Cherokee before the end of the 1600s. The first recorded English trader to live among the Cherokee was Cornelius Dougherty in 1690. The Cherokee traded Native American slaves to the English for use as workers in Virginia and further north.

18th Century: Population Decline

During the 1700s, the number of Cherokee speakers dropped sharply. In the 1730s, the Cherokee population was cut in half because of trade with England. This trade brought diseases like smallpox, which the Native Americans had no protection against. In the 1780s, the Cherokee people faced terrible wars with British settlers, especially the Anglo-Cherokee War, and conflicts with other tribes like the Muscogee.

19th Century: A Time of Change

The Cherokee Syllabary

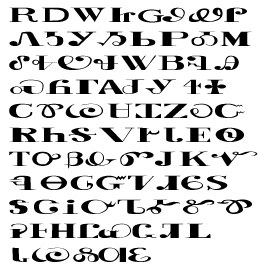

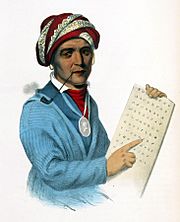

Before the 1820s, Cherokee was only a spoken language. But then, a man named Sequoyah invented the Cherokee syllabary. A syllabary is a writing system where each symbol stands for a whole syllable, not just a single letter sound. Sequoyah's invention was amazing because he couldn't read or write any language himself before he created it!

He first tried to make a symbol for every single word, but that was too hard because there were too many words. He spent a year on this, and his friends and neighbors thought he was crazy. His wife even burned his early work, thinking it was witchcraft. He then tried making a symbol for every idea, but that also didn't work.

Sequoyah finally succeeded when he decided to create a symbol for each syllable in the language. After about a month, he had a system of 86 characters. Some of these symbols looked like letters from the Latin, Greek, or Cyrillic alphabets, but their sounds were completely different in Cherokee. For example, the sound /a/ is written with a letter that looks like a Latin D.

Sequoyah couldn't find adults willing to learn his new writing system, so he taught it to his young daughter, Ayokeh, who was only about six years old. He then traveled to the Arkansaw Territory where some Cherokee had moved. When he tried to show the local leaders how useful the syllabary was, they didn't believe him. They thought the symbols were just random notes. Sequoyah asked each leader to say a word, which he wrote down. Then, he called his daughter in to read the words back. This demonstration convinced the leaders to let him teach the syllabary to a few more people.

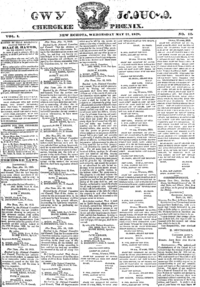

When Sequoyah returned east, he brought a sealed letter from one of the Arkansas Cherokee leaders. By reading this letter, he convinced the eastern Cherokee to learn the system, and it spread very quickly. In 1825, the Cherokee Nation officially adopted the writing system. From 1828 to 1834, American missionaries helped the Cherokee create type characters for Sequoyah's syllabary and print the Cherokee Phoenix. This was the first newspaper of the Cherokee Nation, and it had text in both Cherokee and English.

In 1826, the Cherokee National Council asked George Lowrey and David Brown to translate and print the laws of the Cherokee Nation using Sequoyah's new system.

A scholar named Albert Gallatin thought Sequoyah's syllabary was better than the English alphabet. Even though a Cherokee student had to learn 85 characters instead of 26, they could read right away. Students could learn to read in a few weeks, while English students took two years.

In 1824, the Cherokee leaders gave Sequoyah a large silver medal to honor his invention. It's said that he wore this medal for the rest of his life and it was buried with him.

By 1825, many books and documents were translated into Cherokee, including the Bible, hymns, educational materials, and legal papers. Thousands of Cherokee people learned to read, and the number of Cherokee people who could read their own language was higher than the number of white people who could read English!

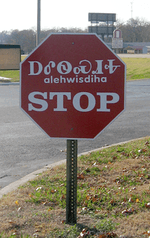

Even though the use of the Cherokee syllabary decreased after many Cherokee were forced to move to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), it has survived. People still use it in private letters, Bible translations, and descriptions of traditional medicine. Today, you can find it in books and on the internet.

The Cherokee Phoenix Newspaper

In 1827, the Cherokee National Council decided to use money to print a newspaper. The printing press and the Cherokee syllabary type were shipped from Boston and then brought by wagon to New Echota, the capital of the Cherokee Nation. The first issue of the newspaper, "Tsa la gi Tsu lehisanunhi" or "Cherokee Phoenix," came out on February 21, 1828. It was printed in both Cherokee and English.

The Cherokee Phoenix (ᏣᎳᎩ ᏧᎴᎯᏌᏅᎯ, Tsalagi Tsulehisanvhi) was the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States, and the first published in a Native American language. It continued until 1834. The Cherokee Phoenix was brought back in the 1900s, and today it publishes online.

The Cherokee Phoenix is now published by the Cherokee Nation as a monthly newspaper in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. It has become modern, publishing on the Web and even being available on the iPhone.

You can find a digital version of the old newspaper online through the University of Georgia Libraries.

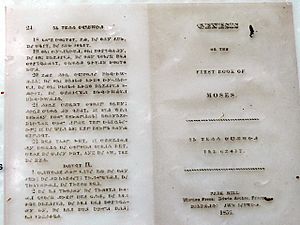

The Cherokee Bible

In 1824, the first part of the Bible was translated into Cherokee. It was John 3, translated by a Cherokee man named At-see (also known as John Arch). People eagerly copied it by hand. He finished the entire Gospel of John by 1824. The complete New Testament was translated in September 1825 by David Brown, another Cherokee man. This was also copied by hand because there wasn't a printing type for the Cherokee syllabary yet. Both Archer and Brown translated the full New Testament into Cherokee.

The very first printed part of the Bible in Cherokee appeared in a missionary magazine in December 1827. It was the first verse of Genesis, translated by Samuel Worcester. In 1828, David Brown and George Lowrey translated Matthew. This was printed in the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper.

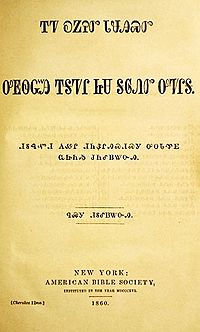

Samuel Worcester and Elias Boudinot, who was the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, published a new translation of Matthew in 1829. This was printed by the Cherokee National Press in New Echota. They continued translating, publishing Acts in 1833 and John in 1838. Worcester, with help from Stephen Foreman, translated many other books of the Bible. The full New Testament was published by the American Bible Society in 1860.

| Translation | John (ᏣᏂ) 3:16 |

|---|---|

| American Bible Society 1860 | ᎾᏍᎩᏰᏃ ᏂᎦᎥᎩ ᎤᏁᎳᏅᎯ ᎤᎨᏳᏒᎩ ᎡᎶᎯ, ᏕᏅᏲᏒᎩ ᎤᏤᎵᎦ ᎤᏪᏥ ᎤᏩᏒᎯᏳ ᎤᏕᏁᎸᎯ, ᎩᎶ ᎾᏍᎩ ᏱᎪᎯᏳᎲᏍᎦ ᎤᏲᎱᎯᏍᏗᏱ ᏂᎨᏒᎾ, ᎬᏂᏛᏉᏍᎩᏂ ᎤᏩᏛᏗ. |

| (Transliteration) | nasgiyeno nigavgi unelanvhi ugeyusvgi elohi, denvyosvgi utseliga uwetsi uwasvhiyu udenelvhi, gilo nasgi yigohiyuhvsga uyohuhisdiyi nigesvna, gvnidvquosgini uwadvdi. |

The Trail of Tears

The Cherokee removal, often called the Trail of Tears, was a sad event where the Cherokee Nation was forced to leave their lands between 1836 and 1839. They were moved from areas in Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Alabama to the Indian Territory (which is now Oklahoma). This forced journey led to the deaths of about 4,000 Cherokee people.

In the Cherokee language, this event is called Nu na da ul tsun yi, which means "the place where they cried." Another term is Tlo va sa, meaning "our removal." However, this second phrase might have come from the Choctaw language. The Cherokee were not the only Native Americans forced to move. Other tribes like the Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Creek Indians also had to leave their homes. The Seminoles in Florida fought against being moved for many years. Some Seminoles stayed in Florida, while others were taken to Indian Territory in chains.

20th Century: Challenges and Resilience

Code Talkers

Native Americans helped the American military by using their languages to send secret messages during wars. The first known use was a group of Cherokee soldiers in September 1918, during World War I. They were part of the American 30th Infantry Division and worked with the British. Their unit realized that the Cherokee language was a perfect way to send messages because the enemy couldn't understand it. Cherokee soldiers also served as code talkers in the 36th Division during World War I. The Cherokee language was later used to send secret messages in the 32nd Infantry Division of the U.S. Army in Normandy, Europe during World War II.

Boarding Schools

During the 1800s and into the 1900s, the United States government set up American Indian boarding schools. The goal of these schools was to make Native Americans adopt Western culture. These schools often discouraged and even banned the use of Native American languages. Students were taught that their tribal identity was not as good as American culture. They were forced to speak and think in English. If they were caught speaking their native language, they were punished, sometimes severely.

A Cherokee Boarding School, started in 1880, also had an English-only rule specifically to get rid of the Cherokee language. The purpose of these schools was to force Cherokee children to become part of mainstream white society. Indigenous children were taken from their homes with the idea of "killing the Indian and saving the man." At these schools, Native American children were given "white" names, clothes, and haircuts, and were forced to speak only English. This school kept its English-only rules until 1933, which had a very negative impact on how many people could speak Cherokee fluently. U.S. policies to make Native Americans adopt American culture lasted into the 1950s.

21st Century: Language Revival

For many years, people wrote Cherokee online by changing the sounds into English letters or by using fonts that didn't work well. However, since the Cherokee syllables were added to Unicode (a system for showing text on computers), the Cherokee language is seeing a comeback on the Internet. The entire New Testament is available online in the Cherokee syllabary. Most Linux computer systems support typing and viewing Cherokee. Windows 8 was the first Windows version to include Cherokee, with almost 180,000 words and phrases in the language. It was the first Windows release in a Native American language.

Starting in 2001, the Cherokee Bible Project began putting the New Testament and parts of Old Testament books online. The New Testament is fully available, as are several Old Testament books like Genesis, Haggai, and Jonah. Cherokee Bible Project

Since 2003, all Apple computers come with a Cherokee font already installed. Cherokee Nation members Joseph L. Erb, Roy Boney, Jr., and Thomas Jeff Edwards worked with Apple to bring official Cherokee language support to the iPhone and iPod Touch in iOS 4.1 (released September 8, 2010) and for the iPad with iOS 4.2.1 (released November 22, 2010). Many apps for learning the Cherokee language are available for Apple devices.

On March 25, 2011, Google announced that you could search in Cherokee. By November 2012, Gmail also supported the Cherokee language.

A video game for learning Cherokee, called "Talking Games," was released in March 2013.

The Cherokee language has also appeared in popular culture, which helps it grow. The theme song "I Will Find You" from the 1992 movie The Last of the Mohicans by the band Clannad features Máire Brennan singing in Cherokee. Cherokee rapper Litefoot includes Cherokee in his songs, as do Rita Coolidge's band Walela and the drum group Feather River Singers.

Books are also helping to expand and develop the Cherokee language. Some books published in Cherokee include:

- Awi Uniyvsdi Kanohelvdi ᎠᏫ ᎤᏂᏴᏍᏗ ᎧᏃᎮᎸᏗ: The Park Hill Tales. (2006)

- Baptism: The Mode

- Cherokee Almanac (1860)

- "Christmas in those Days"

- Cherokee Driver's Manual

- Cherokee Elementary Arithmetic (1870)

- "The Cherokee People Today"

- Cherokee Psalms: A Collection of Hymns in the Cherokee Language (1991)

- Cherokee Spelling Book (1924)

- Cherokee Stories. (1966)

- Cherokee Vision of Elohi (1981 and 1997)

- The Four Gospels and Selected Psalms in Cherokee: A Companion to the Syllabary New Testament (2004)

- Na Tsoi Yona Ꮎ ᏦᎢ ᏲᎾ: The Three Bears. (2007)

- Na Usdi Gigage Agisi Tsitaga Ꮎ ᎤᏍᏗ ᎩᎦᎨ ᎠᎩᏏ: The Little Red Hen. (2007)

The Cherokee Nation now has a radio show called "Cherokee Voices, Cherokee Sounds." It plays songs in Cherokee, interviews Cherokee speakers, and shares news and podcasts in both Cherokee and English. The show has been running since 2004.

Danger of Extinction

In 2019, the Tri-Council of Cherokee tribes announced that the language was in danger of disappearing. They called for more programs to help bring it back to life.

Immersion Education

In 2005, the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Nation started a 10-year plan to save their language. This plan included raising new fluent speakers from childhood through school programs where only Cherokee is spoken. It also involved community efforts to keep using the language at home. The goal was for 80% or more of the Cherokee people to be fluent in the language within 50 years.

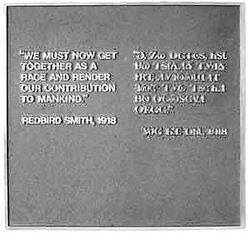

The Cherokee Preservation Foundation has invested $3 million to open schools, train teachers, and create lessons for language education. They also started community gatherings where the language can be actively used. The Kituwah Preservation & Education Program (KPEP), formed in 2006 on the Qualla Boundary, focuses on language immersion programs for children from birth to fifth grade. They also create cultural resources for everyone and community language programs for adults. KPEP runs the New Kituwah Academy, a school where only Cherokee is spoken.

There is also the Cherokee Immersion School in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, which teaches students from pre-school through eighth grade.