Magnus Stenbock facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Magnus Stenbock

|

|

|---|---|

Magnus Stenbock, Georg Engelhard Schröder

|

|

| Born | 22 May 1665 Stockholm, Sweden |

| Died | 23 February 1717 (aged 51) Kastellet, Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Buried |

Uppsala Cathedral, Uppsala, Sweden

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

Swedish Army |

| Years of service | 1685–1717 |

| Rank | Field Marshal (Fältmarskalk) |

| Commands held | Kalmar Regiment Dalarna Regiment |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Eva Magdalena Oxenstierna

(m. 1690) |

Count Magnus Stenbock (born May 22, 1665 – died February 23, 1717) was a Swedish field marshal and Royal Councillor. He was a famous leader in the Carolean Army during the Great Northern War. Magnus was an important member of the Stenbock family.

He studied at Uppsala University and joined the Swedish Army during the Nine Years' War. He fought in the Battle of Fleurus in 1690. After this battle, he became a lieutenant colonel and served in the Holy Roman Empire. He married Eva Magdalena Oxenstierna, whose father was a famous statesman. Later, he returned to Swedish service and became a colonel of different regiments.

During the Great Northern War, Stenbock served under King Charles XII. He helped gather a lot of money and supplies for the Swedish army. King Charles XII really admired him for this. In 1705, he became a general and Governor General of Scania. He showed great skill in managing things and defending Scania against a Danish army. He defeated them at the Battle of Helsingborg in 1710. In 1712, he led a campaign in northern Germany. He defeated a Saxon-Danish army at the Battle of Gadebusch, which made him a field marshal.

His career took a bad turn after he destroyed the city of Altona in 1713. He was surrounded by many enemy troops and had to surrender to King Frederick IV during the siege of Tönning. While he was held captive in Copenhagen, the Danes found out about his secret escape plan. They then imprisoned him in Kastellet. King Frederick IV also started a campaign to make him look bad. Stenbock died in 1717 after years of tough conditions.

Besides being a military leader, Stenbock was also good at speaking, painting, and crafts. His military wins made him a hero in Sweden. Later, during a time when people celebrated national heroes, Swedish historians and artists often praised him. His name is used for streets in many Swedish cities. In 1901, a statue of Stenbock was put up outside the city hall in Helsingborg.

Contents

- Early Life and Family (1665–1680)

- Education and Military Start (1680–1688)

- Nine Years' War (1689–1695)

- Regimental Commander (1695–1700)

- Great Northern War (1700–1713)

- Captivity (1713–1717)

- Death and Burial

- Legacy

- See also

Early Life and Family (1665–1680)

Family Background

Magnus Stenbock was born on May 22, 1665, in Stockholm, Sweden. He was the sixth child of Gustaf Otto Stenbock (1614–1685). His father was a Privy Councillor and a Field Marshal. His mother was Christina Catharina De la Gardie (1632–1704). Her father was the Lord High Constable Jacob De la Gardie.

Magnus was born a count. This is because his father and uncles were made counts by Queen Christina in 1651. The Stenbock family has a long history, going back to the Middle Ages.

Childhood Years

Magnus Stenbock spent most of his childhood with his brothers and sisters. They lived at the pleasure palace Runsa in Uppland. In winter, they moved to Bååtska Palace in Stockholm.

When Magnus was 10, his father, Gustaf Otto, lost his job as Lord High Admiral. He was seen as having failed and had to pay a large fine. This made the Stenbock family's name less respected. Magnus felt this deeply and wanted to bring honor back to his family.

Education and Military Start (1680–1688)

Magnus Stenbock was taught at home starting in 1671. He learned about Christianity, and how to read and write in Swedish and Latin. Later, he had a teacher named Olof Hermelin from 1680 to 1684. Hermelin greatly influenced Magnus's learning.

He taught Magnus about German and French, ancient history, geography, and law. Magnus also learned physical skills like fencing, dancing, and equitation (horse riding). Magnus became very interested in geometry, especially in building forts.

In 1682, Stenbock went to Uppsala University. To finish his studies, he traveled around Western Europe. In 1684, he went to Amsterdam. There, he practiced languages and learned turning (a craft). He also learned to paint realistic birds. Next, he went to Paris and studied mathematics.

In 1685, Stenbock returned to the Netherlands. He got a job as an ensign in a Dutch regiment. This was the start of his military career. In 1687, he served as a captain in Stade, a Swedish area in Germany.

Nine Years' War (1689–1695)

In September 1688, Stenbock became a major in the Swedish army. This army was helping in the Nine Years' War against France. In January 1689, Stenbock was sent to the city of Nijmegen.

Stenbock returned to the front lines in April 1690. On July 1, the big Battle of Fleurus happened. Stenbock was with the Swedish troops on the right side of the army. He saw the army lose badly to the French. During the retreat, Stenbock took command of a Swedish battalion. He managed to lead his troops to safety and even captured some French prisoners.

After the battle, King Charles XI made Stenbock a lieutenant colonel. In 1692, Stenbock was sent to Heidelberg to help German troops. He successfully moved a transport fleet past French artillery. In 1693, he helped defend Heilbronn. Stenbock was appointed colonel in the imperial army in September. He also became an adjutant general in Louis William's army. In 1695, he went to Stockholm to ask for Swedish troops, but the King refused. In 1696, Stenbock left the imperial army.

Marriage and Family Life

In 1686, Stenbock met Eva Magdalena Oxenstierna (1671–1722) in Stockholm. She was the daughter of a powerful statesman. Magnus and Eva wrote many letters to each other. He proposed to her in January 1689.

Their wedding took place on March 23, 1690. Members of the royal family attended. Stenbock became a favorite of King Charles XI and Queen Ulrika Eleonora. His wife's parents helped him in his career.

Magnus and Eva were married for 27 years. But because of Stenbock's military service, they only lived together for seven of those years. They wrote letters often, and Eva visited him in army camps. Stenbock sent money and expensive decorations home. Eva used the money to buy and decorate estates. She managed the family's money and raised their children.

They had eleven children. Five sons and two daughters lived to be adults. Their children later pursued military careers or became judges.

Regimental Commander (1695–1700)

During his military service, Stenbock faced money problems. He had to support his family in Frankfurt. He was offered a job as a colonel for a Hessian regiment, but he turned it down.

In January 1697, Stenbock visited Elector Frederick III in Berlin. He wanted to collect an old debt owed to his father. He got half the money back and sent most of it to his wife.

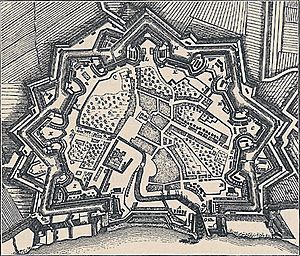

King Charles XI died in April 1697. His son, Charles XII, became the new King. In May 1697, the young King made Stenbock a regimental colonel in Wismar. Stenbock was in charge of repairing Wismar's defenses. He also started writing a war manual called The Swedish Soldier's School. It described different army tactics.

In January 1699, Stenbock became colonel of the Kalmar Regiment. In February 1700, he became colonel of the Dalarna Regiment. This happened thanks to Count Carl Piper and his wife. Before Stenbock could move to his new home, his regiment was ordered to prepare for war. This was the start of the Great Northern War.

Great Northern War (1700–1713)

Early Campaigns in Denmark and the Baltics

The Great Northern War began on February 12, 1700. The King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, August II, attacked Riga. At the same time, King Frederick IV of Denmark invaded Holstein-Gottorp. Russia joined the war in August and attacked Narva.

Stenbock quickly joined his regiment. In July, Swedish troops landed in Zealand, Denmark. Stenbock and his regiment arrived later, making the Swedish force stronger. This forced Frederick IV to sign a peace treaty in August 1700. Stenbock and his regiment then returned to Scania.

In October, Stenbock sailed to Pernau and joined King Charles XII's main army. They marched towards Narva. On November 20, the Swedish army reached Narva. The Russians had built strong defenses. Lieutenant general Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld planned the attack. Stenbock was chosen to lead an advance guard of 516 men.

The Battle of Narva happened on November 20. A heavy snowstorm helped the Swedes. They broke through the Russian defenses, causing panic. The Russian army surrendered. About 9,000 Russian soldiers died, and their leaders were captured. Stenbock was hit in the leg by a musket ball. The Russian army commander surrendered to Stenbock.

Stenbock was in bed for two weeks. King Charles XII visited him and promoted him to major general of infantry. Stenbock became part of the King's inner circle. In December, Stenbock led 600 men into Russian territory. They faced strong Russian troops and a blizzard. Stenbock had to retreat. Only 100 of his 600 men were still able to fight when they returned.

Stenbock continued to impress King Charles XII. He arranged a large feast and a theater show for the King. He also organized a huge snowball fight, like a battle. The King loved these events. He gave Stenbock a horse and made him a general drill instructor. Stenbock's drills helped create new rules for the infantry.

Campaigns in Poland

In June 1701, the Swedish army marched south to fight Augustus II. Stenbock helped build a floating bridge to cross the Daugava river. The crossing was successful.

King Charles XII decided to fight Augustus II in Poland. In January 1702, the Swedish army entered Poland. Stenbock and his regiment were sent to Vilnius. They were ordered to find enemy troops and collect supplies. Vilnius was captured in March. In the Battle of Vilnius on April 6, the Swedish soldiers fought hard and pushed back the attackers.

Stenbock and his troops marched to Warsaw. Stenbock used his engineering skills to build bridges. In July 1702, Charles XII's army met Augustus II at Kliszów. Stenbock's troops joined the main army. On July 9, the battle began. Stenbock fought with the infantry. The Swedes won, forcing Augustus II to retreat. Stenbock later said this was his hardest battle.

After the battle, Charles XII decided to take Kraków. Stenbock was sent to scout the city. After a short fight, Charles XII and Stenbock captured the city. Stenbock was made Commandant of Kraków. He had to collect 60,000 riksdaler from the citizens. He collected the money quickly. Charles XII gave Stenbock 4,000 riksdaler as a gift. Stenbock became the highest Swedish official in Kraków.

Leading the War Commissariat

On August 18, 1702, Stenbock became the director of the General War Commissariat. He was in charge of getting food for the army. He sent officers to each regiment to help collect supplies. In October, Stenbock led 3,000 men to Galicia. His job was to collect money and force local nobles to stop supporting King Augustus.

When some officials failed to collect money, Stenbock took strong action. On October 28, he burned down the city of Pilzno as an example. Other villages were also burned. From Galicia, Stenbock collected over 300,000 riksdaler. He also got food, wagons, and clothes. Stenbock's actions made many Polish nobles angry at the Swedes.

In April 1703, Stenbock fought in the Battle of Pułtusk. In May, Charles XII started the siege of Thorn. Stenbock helped transport cannons for the siege. The city was captured in October.

In 1704, Stenbock created his own dragoon regiment. He also helped the King occupy and plunder Lemberg. Stenbock often led the King's advance troops. He was also in charge of collecting supplies. On November 4, Stenbock was promoted to lieutenant general of infantry. He was very proud of this.

In 1706, Stenbock joined Charles XII in the blockade of Grodno. In August 1706, the Swedish army marched into Saxony. A peace treaty was signed in September. King Augustus II had to give up his claim to the Polish crown.

In July, Stenbock was promoted to general of infantry. On December 25, 1705, he became Governor-General of Scania. In April 1707, he had his last meeting with Charles XII. He then went home to Sweden.

Governor-General of Scania

On June 4, 1707, Stenbock arrived in Malmö. He reunited with his family. He started his job as governor on September 18. Scania was in a difficult situation. It was close to Denmark and had lost many men to the war. Also, the previous governor had managed things poorly.

Stenbock found that the financial records were a mess. He replaced the deputy-governor with his own accountant. In October and November 1707, Stenbock toured Scania. He found that peasants were paying very high taxes. Many villages were empty. Stenbock reported this to the Privy Council in Stockholm. They agreed to investigate, and many corrupt officials were arrested.

Stenbock also worked on other issues. He fought against shifting sand on farms. He put up milestones on roads. He planted trees to help with wood shortages. He also hired land surveyors.

Stenbock spent time with his family at different estates. He used the governor's residence in Malmö for official events. He also spent time at Vapnö Castle, which he inherited. He enjoyed artistic activities there. His wife managed the estates and their horse farm.

In the summer of 1709, Stenbock heard that Denmark was preparing for an invasion. Danish warships were loading troops and supplies.

War in Scania

News spread about Charles XII's terrible defeat at the battle of Poltava in Ukraine in June 1709. The Swedish main army was destroyed. Charles XII escaped to the Ottoman Empire. Denmark and Saxony rejoined the war against Sweden. Danish-Norwegian troops invaded Scania.

Stenbock called a meeting in Malmö. He said the city's defenses needed to be stronger. Malmö was important for defending Scania. Landskrona also needed help. Stenbock asked for more soldiers and supplies. He reinforced the coastal guard. He had few regiments, and most were poorly equipped.

On August 22, Stenbock reported the Danish threat. The Defense Commission sent cavalry regiments to Scania. Stenbock also gathered 3,000 new troops. In September, he told the people of Scania to stay loyal to the King. On September 27, 1709, Stenbock gave a powerful speech in Malmö. He told the citizens not to worry about Poltava. He reminded them of their duty to their King and country. He said he was ready to die with them.

Danish Invasion and Swedish Response

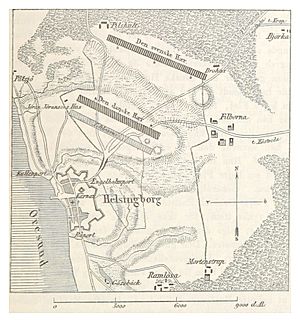

The Danish declaration of war arrived on October 18. Malmö's defenses were ready. On October 31, a large Danish fleet sailed from Copenhagen. The Danish army had 15,000 men. Christian Ditlev Reventlow was their general. Stenbock saw the fleet on November 1. The Danes landed south of Helsingborg. Stenbock decided to retreat, destroying bridges. By November 5, the Danes had taken Helsingborg without a fight.

In November, the Danes occupied central Scania. They blockaded Malmö and Landskrona. Stenbock was ordered to leave Malmö and lead a new Swedish army. He left Malmö on December 1. On December 7, he set up his headquarters in Kristianstad. Stenbock wanted to attack quickly. But he was told to wait for the Swedish army to gather.

On January 3, 1710, Reventlow marched towards Kristianstad. He wanted to capture Karlskrona. Stenbock moved his troops and supplies. He organized defenses in Karlshamn. On January 13, Danish troops attacked at Torsebro. The Swedes had to retreat. Eastern Scania fell to the Danes.

Stenbock gathered his remaining troops. He got permission to recruit more soldiers. On January 20, Stenbock went to Växjö to assemble the field army. More troops arrived over the next few days. By February 11, Stenbock commanded 19 regiments and about 16,000 men.

Swedish Counterattack: Battle of Helsingborg

On February 12, the army marched south. They met a Danish patrol in the forests of Hästveda. The Danes retreated. Reventlow heard about the Swedish advance. He decided to retreat to Helsingborg. On February 17, Reventlow became ill and gave command to Jørgen Rantzau.

On February 18, Stenbock crossed the River Rönne. Rantzau ordered his troops to return to Helsingborg. Stenbock pursued them. On February 24, Stenbock returned to his army with supplies and 24 cannons. He decided to fight the Danes. His troops moved towards the heights north of Helsingborg.

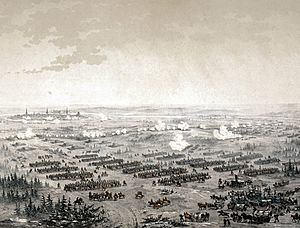

On the morning of February 28, Rantzau's Danish army of 14,000 men was ready. Stenbock's army also had 14,000 men. Stenbock used a clever move to get past the Danish defenses. This forced the Danes to leave their strong position. A fierce cavalry fight began. The Swedish infantry attacked the Danish center. The Danish line broke apart.

The Danes fled to Helsingborg's forts. The battle lasted three hours. The Danes lost 1,500 dead and 3,500 wounded. They also had 2,700 prisoners. The Swedes lost 900 dead and 2,100 wounded. Stenbock hurt his back when he fell from his horse.

The Danes hid in Helsingborg. Stenbock started bombarding the city on March 3. King Frederick IV ordered the city to be evacuated. The Danes burned their wagons and left thousands of dead horses. On March 5, the last Danes left Scania. Stenbock then had farmers clean up the city.

Stenbock's victory at Helsingborg made him a hero in Sweden. He received congratulations from important people. His victory was celebrated across Sweden. In April, Stenbock went to Stockholm. He was cheered by the citizens. On May 21, he was appointed field marshal.

Plague Outbreak and Royal Councillor

In the summer of 1710, Sweden had a bad harvest. Soldiers in Scania stole food from farmers. Stenbock could not control them. At the same time, a serious illness spread in Stockholm. It was the bubonic plague.

Stenbock decided to isolate Scania to stop the plague. Armed guards were placed on major roads. Travelers had to show health papers. Letters were also fumigated. Between 1710 and 1713, 100,000 people in Sweden died from the plague. Thousands died in Scania.

In February 1711, Stenbock received an order from Charles XII. He had to leave his governor post and become a Royal Councillor in Stockholm. Stenbock felt this was a step down. He would get less money. However, he was still in charge of Scania's border defense.

Charles XII wanted to send an army to Pomerania. Stenbock supported this plan. He was given the task of putting together this new army. In April 1711, Stenbock argued for the King's order. Denmark, Russia, and Saxony then attacked Pomerania. King Stanisław Leszczyński, who was protected by Sweden, asked for more troops.

The Privy Council agreed to send 4,000 men to Stralsund. Stenbock helped with the troop transport. The fleet sailed in November. Stenbock returned to Karlskrona. In December, he was ordered to guard the Swedish west coast.

Mobilization for Germany

On May 19, 1712, Stenbock received a new order from Charles XII. He had to immediately send an army to Pomerania. He could do this without the Privy Council's approval. Stenbock also had to work with King Stanisław Leszczyński.

Stenbock needed a lot of money and sailors for the transport. The Privy Council could only give him a quarter of what he asked for. Stenbock then started a campaign to borrow money from wealthy people in Stockholm. He also asked for cargo ships. In a short time, he collected 400,000 daler and nine large ships.

Stenbock said goodbye to his family. In August, a fleet of 27 warships sailed. Stenbock joined the transport fleet. They sailed for Rügen. The next day, the Swedish fleet chased away a Danish fleet.

Campaign in Northern Germany

On August 25, Stenbock landed on Rügen. On September 16, 9,500 men and twenty guns landed. Most troops stayed on Rügen. On September 18, a Danish fleet attacked the transport ships. Over 50 Swedish ships were lost, and many winter supplies.

This was a big loss for Stenbock. He asked the Privy Council for new supplies and more cavalry. Stenbock also started secret talks with the Saxon Field Marshal. The talks did not lead to peace. Stenbock decided to march west to Mecklenburg to find supplies.

On November 1, 16,000 men marched out of Stralsund. They entered Rostock without a fight. Stenbock set up his headquarters in Schwaan. They collected a lot of food and horses in Mecklenburg. Stenbock negotiated a two-week ceasefire. This allowed the Swedes to gather more food. King Stanisław left to tell Charles XII about the talks. Stenbock stayed in Wismar due to illness.

Battle of Gadebusch

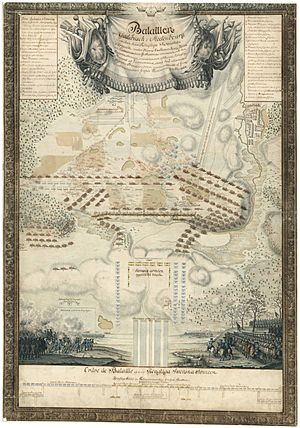

After the ceasefire, Stenbock learned that a large Danish army had entered Mecklenburg. He decided to attack them before they could join other allies. On December 15, the Swedes destroyed bridges to protect their army. On December 19, Stenbock camped near Gadebusch.

On the morning of December 20, the Danes took defensive positions. Saxon troops arrived to reinforce them. Stenbock's army had about 14,000 men. The Danes and Saxons had 19,500 men. Stenbock used his artillery effectively. The Swedish cavalry attacked the Danish left wing. The Danes fled, but Saxon troops stopped the Swedish advance.

The Swedish infantry attacked the Danish center. The Danish line broke apart. The battle ended at dusk. The remaining Danish and Saxon troops retreated. Danish losses were 2,500 dead and injured. Saxon losses were 700-900. The Swedes lost 550 killed and 1,000 injured.

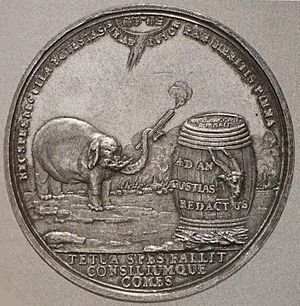

Stenbock's victory was celebrated in Sweden. He received many congratulations. King Louis XIV of France even mentioned him. Charles XII officially made Stenbock a Field Marshal in January 1713.

The Burning of Altona

On December 30, Stenbock marched into Holstein. He demanded money and supplies from the area. He also asked for clothes for his troops. The Governor General, Mauritz Vellingk, wanted to get revenge on the Danes. He told Stenbock to destroy the Danish city of Altona.

On January 7, 1713, Stenbock entered Altona. He arrested the city's leaders. The citizens offered to pay a ransom. Stenbock discussed this with Vellingk. Vellingk insisted that Altona must be burned. He said it was important for the Allies. Stenbock disagreed, saying it would cause revenge attacks. But Vellingk threatened him.

Stenbock returned to Altona. He demanded a huge ransom by midnight. The citizens could not collect the money. Stenbock left Altona and ordered it to be burned.

On the night of January 8-9, Altona was set on fire. Hundreds of citizens died in the flames or froze. Only a few hundred houses survived. Stenbock said he was forced to do it. But the Allies strongly criticized his action. He became known as a cruel arsonist. His actions were called "the Swedish Bonfire."

In mid-January, enemy troops approached Hamburg. Stenbock and his army marched into Schleswig. They camped in Husum. Stenbock decided to occupy the Eiderstedt peninsula. He wanted to use the fortress of Tönning for protection. Stenbock made a secret treaty with Holstein-Gottorp. The Swedes would protect the Duchy, and Tönning would protect them.

Enemy troops crossed the Eider Canal. Stenbock's troops fought Russian troops. Stenbock retreated towards Tönning. He lost cannons and food. The Swedish army entered Tönning on February 14. Stenbock tried to get reinforcements from Sweden, but failed. Half of his cavalry surrendered to the Russians. The rest went back to Tönning.

Surrender at Tönning

Inside Tönning, 12,000 Swedes were crowded. There was not enough firewood, food, or water. The Privy Council in Sweden could not send help. From the sea, Danish warships blocked Tönning. Stenbock could not expect help from Charles XII.

Stenbock became depressed. He argued with the fortress commander. He wrote angry letters to the Privy Council. He blamed others for his problems. He was told that the fortress only had supplies for three months. The enemy troops were getting closer. Stenbock was advised to consider surrendering.

When Stenbock's troops entered Tönning, the Danes saw Holstein-Gottorp as an enemy. Danish troops occupied parts of Schleswig.

A baron named Görtz tried to help Holstein-Gottorp. He convinced Frederick IV that the Duchy was not involved. Görtz got a letter promising Holstein-Gottorp's rights back if the Swedes surrendered. Görtz returned to Tönning on April 16. By then, 2,000 Swedish soldiers had died. Diseases were spreading.

Stenbock and his officers agreed to negotiate. A Swedish group was sent to talk with the Danes. On April 21, the Danes gave an ultimatum. The Swedes had to give up their weapons and cannons. Stenbock refused. But Frederick IV stopped all talks.

Stenbock was invited to Oldenswort for direct talks with Frederick IV. The negotiations lasted over a week. The final agreement still meant the Swedes had to give up their weapons. But they could keep their luggage and uniforms. They would also be sent back to Sweden later. Tönning would stay with the Duchy.

After a final meeting, Stenbock accepted the terms. The surrender agreement was signed on May 16. Stenbock sent a letter to Charles XII about his surrender. On May 20, about 9,000 Swedish soldiers marched out of Tönning. They were taken to Danish prison camps. Stenbock went with Frederick IV as a guest.

Captivity (1713–1717)

Life as a Prisoner

During his captivity, Stenbock paid 8,000 riksdaler for the prisoners' needs. By Christmas 1713, about half of the 10,000 Swedish prisoners had died. Stenbock spent his time on his art. He also wrote defenses, blaming others for his surrender.

In June, some money was sent for the prisoners. But it was not enough to free them. The Privy Council in Sweden gave up hope of releasing the prisoners. They said Sweden's resources were needed for defense.

On November 20, Stenbock was moved to Copenhagen. He lived in the Marsvin Estate. Danish guards watched him closely. Stenbock could move around Copenhagen with his guards. All his letters and books were checked. He started writing another defense, blaming others.

Stenbock's stay attracted people from Copenhagen's rich circles. They wanted to see him. He made contacts who helped him send secret letters. He used fake names in his letters. He exchanged letters with his wife, Eva. She sent him information and gifts.

Escape Plan and Imprisonment

At first, Stenbock did not want to escape. But when release seemed impossible, he changed his mind. On May 1, 1714, he wrote to Charles XII about escaping. He approved a plan to rent a ship to take him to Sweden.

The plan was for a Prussian skipper to smuggle him out of his home. But Stenbock called off the plan on July 13. He thought it was too risky. He also noticed that his guards were stricter. He complained about the strict watch. He burned drafts of his letters.

A few days later, Stenbock was confined to two rooms. More guards were added. The skipper who was supposed to help him escape was arrested. King Frederick IV knew about Stenbock's plan. A spy had been reading his secret letters. The spy also found Stenbock's secret documents in Hamburg. These documents included his treaty with Holstein-Gottorp. This treaty was important evidence against Stenbock.

When Stenbock's servants were questioned, they revealed how they helped him.

On November 17, 1714, Stenbock was moved to Citadellet Frederikshavn. He was told he could no longer talk to the outside world. He lived in the commandant's house. He immediately wrote to Frederick IV, denying he planned to escape. He also wrote secret letters to Charles XII, complaining about the Danes. These letters were found by a guard.

Stenbock was moved to a special prison. It had barred windows. The rooms were dark and damp. Frederick IV started a new investigation against Stenbock. On December 20, 1714, Stenbock was questioned. His escape plan and secret treaty were revealed. Stenbock was very worried about his reputation. He was accused of spying and insulting the Danish King. Stenbock wrote to Frederick IV, begging him not to call him a spy.

It took over a year for Frederick IV to reply. A historian wrote a public accusation against Stenbock. It used Stenbock's own letters to show his escape plan and his complaints about the King. Stenbock's appeals were made to look fake. Stenbock was painted as not being an honorable man.

Stenbock wrote a long defense. He explained his failed campaign in Germany. He said others forced him to burn Altona. He said he was tricked into surrendering Tönning. He also said Frederick IV treated him and other Swedish prisoners unfairly. He expressed sadness for his failures and for not spending enough time with his family. He wrote that he was ready to die.

During his last years, Stenbock's health got worse. He had constant pain. He also started losing his eyesight. He had to fire servants who stole from him. The food he received was bad. In August 1716, Tsar Peter I visited him. Stenbock complained about his captivity. The Tsar told Frederick IV, and Stenbock got better meals. Stenbock also learned that his daughter, Ulrika Magdalena, had died. This made him lose his will to live.

Death and Burial

Stenbock died on February 23, 1717, in his prison cell. The exact cause of death is not known. It was likely due to his long illness and poor health. His defense writings were secretly brought to Sweden.

Frederick IV ordered Stenbock's belongings to be recorded. Stenbock was buried with military honors in Copenhagen. His coffin was later moved to Sweden in November 1719. It was taken to Vapnö Castle Church. He stayed there until his wife died in 1722. Then, Magnus and Eva were buried together in the Oxenstierna family crypt in Uppsala Cathedral.

Legacy

Magnus Stenbock is seen as a hero in Swedish history. He is also part of Swedish folklore. Through his letters and speeches, Stenbock was able to protect his reputation. He became known as a brave military leader. His heroic image grew in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Historians called him "the great Carolean."

Artists and poets also portrayed Stenbock. He appears in historical paintings and poems. However, in other countries, opinions of Stenbock have been less positive. Polish historians called him a war criminal. In Schleswig-Holstein, he was remembered for burning Altona. But Danish historians have written more positively about him.

Stenbock's writings were put together in a book in 1721. Many biographies have been written about him.

An equestrian statue of Magnus Stenbock was unveiled on December 3, 1901, in Helsingborg. It was a big celebration. King Oscar II sent a telegram, praising Stenbock. The statue is one of the few non-royal equestrian statues in Sweden. It was moved in 1959 for traffic reasons. Today, newly graduated students in Helsingborg walk seven laps around the statue every June.

Stenbock is honored in other ways in Helsingborg. A former school, a church, and a mall are named after him. A train in Scania is also named Magnus Stenbock. Streets are named after him in about 30 Swedish cities.

See also

In Spanish: Magnus Stenbock para niños

In Spanish: Magnus Stenbock para niños