Marcellus Formation facts for kids

The Marcellus Formation or Marcellus Shale is a type of sedimentary rock found in eastern North America. It formed during the Devonian Period, about 390 million years ago. This rock unit is named after a special place near the village of Marcellus, New York, where it can be seen clearly. The Marcellus Formation stretches across a large area called the Appalachian Basin.

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) uses both "Marcellus Shale" and "Marcellus Formation." "Marcellus Shale" is often preferred in the Appalachian region. The geologist J. Hall first described and named it "Marcellus shales" in 1839.

Quick facts for kids Marcellus FormationStratigraphic range: Middle Devonian |

|

|---|---|

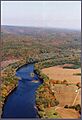

Marcellus shale exposure above Marcellus, N.Y. The vertical joints create sheer cliff faces.

|

|

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Hamilton Group |

| Sub-units | See: Named members |

| Underlies | Mahantango Formation and Millboro Shale |

| Overlies | Huntersville Chert, Needmore Shale, and Onondaga Formation |

| Thickness | up to 900 feet (270 m) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Shale |

| Other | Slate, limestone, sandstone |

| Location | |

| Region | Appalachian Basin of eastern North America |

| Extent | 600 miles (970 km) |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Marcellus, New York |

| Named by | James Hall, 1839 |

Contents

- What is the Marcellus Shale?

- Where is the Marcellus Shale Found?

- How the Marcellus Shale Shapes the Land

- Layers of the Marcellus Shale

- Fossils in the Marcellus Shale

- How Old is the Marcellus Shale?

- What Resources Come from the Marcellus Shale?

- Engineering Challenges with Marcellus Shale

- Images for kids

What is the Marcellus Shale?

The Marcellus Shale is mostly made of dark, black shale. It also contains some layers of limestone and small amounts of iron minerals like pyrite (also known as "fool's gold") and siderite.

How the Shale Breaks

Like most shales, the Marcellus breaks easily into thin, flat pieces. This property is called fissility. When exposed to air, the lighter colored shales on top can break into small, sharp pieces. These pieces might show rust stains because the pyrite reacts with air. You might also see tiny gypsum crystals forming from reactions between pyrite and limestone.

Minerals and Radioactivity

Freshly exposed shale with pyrite can develop orange limonite and pale yellow sulfur on its surface. Pyrite is very common near the bottom of the formation. The Marcellus also contains uranium. The natural breakdown of uranium-238 creates radon gas, which is radioactive.

Organic Content and Energy

The Marcellus Shale has a lot of organic material, from less than 1% to over 11%. This means it has enough carbon to burn. These dark shales are important because they are a "source rock" for petroleum (oil) and natural gas. They filled underground "reservoirs" with oil and gas. The Marcellus is also a source of "shale gas," which is natural gas trapped within the shale itself. It also acts as an "impermeable seal," meaning it's a layer that gas cannot easily pass through, trapping gas in layers below it.

In some western areas, the formation can produce liquid oil. Further north, deep burial and heat over millions of years changed this oil into gas.

Where is the Marcellus Shale Found?

The Marcellus Shale is found across the Allegheny Plateau in the northern Appalachian Basin. In the United States, it runs through New York, Pennsylvania, eastern Ohio, western Maryland, and most of West Virginia. It also extends into western Virginia, a small part of Kentucky, and Tennessee. Under Lake Erie, it crosses into Canada, stretching across southern Ontario.

Marcellus Outcrops in New York

You can see the Marcellus Shale exposed at the surface, called "outcrops," along the northern edge of the formation in central New York. Here, the rock has two sets of cracks, called joints, that are almost at right angles to each other. These joints create smooth, nearly vertical cliffs. When exposed to weather, the rock faces lose most of their dark color, turning from black to a lighter gray.

Early in the 1800s, people dug into Marcellus outcrops in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. They hoped to find coal because some small beds looked like coal. However, this "false coal" was not valuable fuel. It was likely formed from ancient seaweed and marine plants, not land plants, which is what true coal comes from.

The Marcellus bedrock is close to the surface in an east-west band through Syracuse. This area has a higher risk of radon gas as an indoor air pollutant. Further south in Pennsylvania, the formation goes much deeper, more than 2,700 meters (8,858 feet) below the surface.

How the Marcellus Shale Shapes the Land

The Marcellus Shale is easily eroded. It often lies beneath low areas between some Appalachian ridges, forming long, narrow valleys. The soil that forms from the Marcellus and other shales nearby is deep and good for agriculture.

The soft shale also guides the path of streams and rivers, creating straight sections in valleys. For example, the Delaware River follows the Marcellus beds for about 40 kilometers (25 miles) along the Pennsylvania–New Jersey state line. This area is a "buried valley," where the river flows over glacial material that covers the eroded Marcellus bedrock.

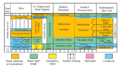

Layers of the Marcellus Shale

Geologists study the layers of rock, which is called stratigraphy. The Marcellus is the lowest unit of the Devonian-age Hamilton Group. It is divided into several smaller units.

In 1839, James Hall named the unit "Marcellus Shale" after the place where it was best seen. He believed that naming rock units after locations was better than naming them after how they looked, because appearances can change. His idea was widely accepted.

Layers Above the Marcellus

Today, the Marcellus Shale is the bottom layer of the Hamilton Group. Above it lies the Mahantango Formation in Pennsylvania and Maryland. In New York, the Mahantango is further divided. The Marcellus is separated from the overlying Skaneateles Formation by a thin layer of limestone called the Stafford or Mottville Limestone.

In West Virginia, the Marcellus might be directly below the younger Harrel Formation. This is due to a disconformity, which means there's a gap in the rock record, perhaps from a period of erosion.

Layers Below the Marcellus

The Marcellus Shale usually sits on top of the Onondaga Formation. The contact between them can be sharp or gradual. In Canada, the Marcellus lies over the Dundee Formation, which is similar to the Onondaga.

In eastern New York, the Marcellus and Onondaga layers blend together. In western New York, the Union Springs member of the Marcellus lies on top of the Seneca member of the Onondaga Limestone. Sometimes, the Cherry Valley Limestone member of the Marcellus sits directly on the Onondaga, meaning the Union Springs shale is missing.

In West Virginia, the Marcellus lies over the Onesquethaw Group, which includes the Needmore Shale and Huntersville Chert. To the south, the Hamilton Group changes into the Millboro Shale in southern West Virginia and Virginia.

Tioga Ash Beds

At the base of the Marcellus in eastern Pennsylvania, there's a special layer about 0.6 meters (2 feet) thick called the Tioga ash beds. These layers are made of volcanic ash from ancient eruptions. Geologists use the Tioga ash beds as a marker to identify the Marcellus and other rock layers.

These ash beds are found across a huge area, more than 265,000 square kilometers (102,000 square miles), from Virginia to New York. Explosive volcanic eruptions in what is now central Virginia released the ash. It was spread by winds across the Appalachian, Michigan, and Illinois Basins. The ash is different from other sediments because its quartz grains are sharp, not rounded by erosion.

The Tioga ash can be gray, brown, black, or olive. It contains mica flakes and coarse crystals. There are eight main ash beds, labeled A (oldest) to H (youngest), plus another called the Tioga middle coarse zone. These ash beds are found in the Marcellus or the layers just below it. This shows that the Marcellus started forming earlier in some areas than others.

How Thick is the Marcellus Shale?

The Marcellus Shale varies in thickness. It can be up to 270 meters (886 feet) thick in New Jersey, but only 12 meters (39 feet) thick in Canada. In West Virginia, it's about 60 meters (197 feet) thick. In eastern Pennsylvania, it's 240 meters (787 feet) thick, but it gets thinner to the west, becoming only 15 meters (49 feet) thick along the Ohio River.

The thinning from east to west happens because the sediments that formed the rock came from the east. The layers eventually "pinch out" (disappear) to the west because a bulge in the Earth, called the Cincinnati Arch, limited how far the sediments could spread. Where the formation is thick, it is divided into several smaller units.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Named Members of the Marcellus

The Marcellus Formation is divided into several named parts, or "members." For example, in eastern Pennsylvania, the Purcell limestone member divides the Marcellus. This layer is similar to the Cherry Valley Limestone member in New York. Other members include the Bakoven Shale, Cardiff Shale, Chittenango shale, Solsville sandstone, Union Springs shale and limestone, and Stony Hollow shale and limestone.

The Union Springs member is rich in organic material and pyrite. To the east, it becomes the Bakoven Member. In western New York, the Union Springs layers thin out.

In Western and central New York, the Oatka Creek shale is the top member. The Chittenango Member is made of dark, black shales that split easily. Further east, the Cardiff member divides into the Bridgewater, Solsville, and Pecksport shale members.

In south central Pennsylvania, the Marcellus has three members: the Mahanoy Member, the Turkey Ridge Member, and the Shamokin Member.

Fossils in the Marcellus Shale

The Marcellus Shale contains fossils of ancient marine animals, even though they are not very common. These fossils are important for understanding ancient life. For example, the Marcellus has the oldest known collection of thin-shelled mollusks with well-preserved shells.

Ancient Sea Creatures

It's also where goniatites, which were ancient shelled creatures similar to squid, first appear in the fossil record. You can find fossils of large, clam-like animals called brachiopods, like Spinocyrtia. Molds of crinoids, which are plant-like animals related to starfish, are also found. Small, cone-shaped tentaculitids are common in the Chittenango Member.

The Solsville member contains well-preserved bivalves (clams), gastropods (snails), and brachiopods. These creatures lived on the seafloor in ancient marine environments. The fossils show that the bottom layers were dominated by "deposit feeders" (animals that eat organic matter from the sediment), while the upper layers had more "filter feeders" (animals that filter food from the water).

Unique Fossil Beds

The Cherry Valley Member is known for its rich collection of nautiloid and goniatite cephalopod fossils. It was even called the Goniatite Limestone because of these fossils. It also contains the "Cephalopod Graveyard" in New York, where many large adult cephalopods gathered and died. This bed lacks young fossils, suggesting it might have been a breeding ground.

How Old is the Marcellus Shale?

On the geological timescale, the Marcellus Formation is from the Middle Devonian epoch. This means it formed about 391.9 to 383.7 million years ago. A sample from Pennsylvania was dated to 384 million years old.

The Union Springs member, at the bottom of the Marcellus in New York, is from the end of the Eifelian stage, which came just before the Middle Devonian. Dark shales in the formation show evidence of the Kačák Event. This was a time when the ocean lacked oxygen, which led to an extinction event for some marine life.

What Resources Come from the Marcellus Shale?

The Marcellus Shale holds large amounts of natural gas that haven't been fully used yet. Because it's close to big cities on the East Coast of the United States, it's an important source for energy.

Natural Gas Production

The Marcellus natural gas area covers 104,000 square miles across Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, and New York. It is the largest source of natural gas in the United States. To get the gas out of the shale, a method called hydraulic fracturing (or "fracking") is used. This involves injecting liquid at high pressure to create cracks in the rock, allowing the gas to flow. Since 2008, drilling in the Marcellus Shale has brought economic benefits but also raised environmental concerns.

Iron Ore

The black shales also contain iron ore, which was used in the past to make iron. At the bottom of the Marcellus, where pyrite, carbonate, and groundwater mixed, a usable brown hematite iron ore formed. This iron ore was mined in south Central Pennsylvania from the late 1700s until the early 1900s.

The ore was easy to find and dig up from shallow pits. However, deeper deposits were often unusable because they still contained pyrite. The iron ore was turned into "pig iron" in stone blast furnaces. Iron products from this area were known as "Juniata Iron." These furnaces were important for the local economy but used a lot of wood from nearby forests, which eventually led to their decline.

The quality of the iron ore from the Marcellus varied. Some ore contained a lot of carbon and sulfur. Sulfur made the iron "red-short," meaning it would crack easily when heated. However, some locations in Pennsylvania had very good quality ore with high iron content and low sulfur.

Iron Pigments

Water reacting with pyrite in the Marcellus also created a type of bog iron near some outcrops. In the 1800s, this iron ore was used as a mineral paint pigment. After being heated and ground, it was mixed with linseed oil to paint barns, bridges, and railroad cars.

Healing Waters

People in the past believed that iron-rich waters from springs near the Marcellus Shale had healing powers. The Bedford Springs Hotel in Pennsylvania was built in 1802 around these "iron springs." These waters contained dissolved iron carbonate, which gave them a slightly "inky taste."

Other Uses of the Shale

The Marcellus Shale has also been used locally for aggregate (material for building) and common fill. However, shales with pyrite are not good for this because they can cause acid drainage and expand in volume. In the 1800s, this shale was used for walkways and roads because its fragments packed tightly and drained well.

The dark, slaty shales were also quarried for low-quality roofing slate and school slates in eastern Pennsylvania during the 1800s.

Scientists are also looking into whether carbon-rich shales like the Marcellus could be used for carbon capture and storage. This would involve injecting carbon dioxide into the formation to help reduce global warming. This process might also help recover more natural gas.

Engineering Challenges with Marcellus Shale

The Marcellus Shale is easily eroded, which creates challenges for civil and environmental engineering projects.

Acid Rock Drainage

When the shale is exposed during road construction, the pyrite in it can react with air and water. This creates acidic surface runoff after rain. This acidic runoff can harm aquatic ecosystems (water environments). Highly acidic soil contaminated by this runoff cannot support plants, which can lead to soil erosion.

Slope Stability and Expansion

The shale naturally breaks down into smaller pieces, which can affect the stability of slopes. This means that construction projects need to create shallower slopes, disturbing more land. The excavated shale cannot be used as fill material under roads or buildings because it expands.

Damage to structures built on Marcellus shale fill has occurred due to expansion. This happens when sulfuric acid from pyrite reacts with calcite in the shale to produce gypsum, which takes up more space. This expansion can create strong pressure, enough to lift building foundations.

Drilling Issues

Drilling through the Marcellus Shale can also be difficult. The shale has a low density and may not react well with some drilling fluids. The shale is also fragile and can fracture under pressure, causing problems with circulating drilling fluid. The formation may also have low pressure, making drilling even more complicated.

Images for kids

-

Fragments below exposure of fissile Marcellus black shale at Marcellus, N.Y.

-

Delaware River above Walpack Bend, where it leaves the buried valley eroded from Marcellus Shale bedrock

-

Bedrock geologic map showing Marcellus bedrock in New York and Pennsylvania

-

Marcellus exposure along Interstate 80 in eastern Pennsylvania where the formation is thickest.

-

Illustration of a Cephalopod (Goniatites vanuxemi) fossil from the Marcellus Formation.

-

Generalized stratigraphic nomenclature for the Middle Devonian strata in the Appalachian Basin.

-

Geologic cross section of upper to middle Devonian strata from Cherry Valley, New York southwest across the Allegheny Plateau and then along the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians to Tennessee. Note the Marcellus grades up to the Milboro and Chattanooga black shales.