Miami people facts for kids

Kee-món-saw, Little Chief, Miami chief, painted by George Catlin, 1830

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,908 (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States Oklahoma and Indiana |

|

| Languages | |

| English, French, Miami–Illinois | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Traditional tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Peoria, Kaskaskia, Piankashaw, Wea, Illinois, and other Algonquian peoples |

The Miami (in their own language, Myaamiaki) are a Native American nation. They originally spoke the Miami–Illinois language, which is part of the Algonquian languages family. The Miami people lived in the Great Lakes region. Their traditional lands were in what is now north-central Indiana, southwest Michigan, and western Ohio.

Historically, the Miami were made up of several groups, like the Piankeshaw and Wea. Today, when people say "Miami," they often mean the Atchakangouen group. By 1846, most Miami people were moved to Indian Territory. This area is now part of Oklahoma. The Miami Tribe of Oklahoma is the official, federally recognized tribe in the United States. Another group, the Miami Nation of Indiana, is made up of Miami descendants who stayed in Indiana. They are still working to get official recognition.

Contents

The Miami People and Their History

What Does "Miami" Mean?

The name "Miami" comes from Myaamia, which is what the tribe called themselves in their own language. This word might mean "downstream people." Some people thought the Miami called themselves Twightwee. This name was thought to sound like the call of their sacred bird, the sandhill crane. However, recent studies show that Twightwee actually came from another tribe's name for the Miami. The Miami also called themselves Mihtohseeniaki, meaning "the people." They still use this name today.

Early History of the Miami Tribe

The early Miami people were part of the Fisher Tradition of the Mississippian culture. These societies grew maize (corn) and had organized communities with leaders. They also traded with other groups. The Miami were skilled hunters, just like other Mississippian peoples.

Written records about the Miami began when missionaries and explorers met them in what is now Wisconsin. From the mid-1600s to the mid-1700s, the Miami moved south and east. They settled along the upper Wabash River and the Maumee River in Indiana and Ohio. According to their oral history, this move was a return to their ancient lands. They had left these lands earlier because of attacks during the Beaver Wars. During these wars, the Iroquois tribe, who had European firearms, tried to control the fur trade in the Ohio Valley. This caused many Algonquin tribes to flee west. Along with warfare, European diseases like measles and smallpox also greatly reduced Native American populations.

Meeting Europeans

When French missionaries first met the Miami in the mid-1600s, the tribe lived near Lake Michigan. The Miami say they moved there a few generations before to escape the Iroquois. The Iroquois were trying to control the fur trade in the Ohio Valley. Early French explorers noticed that the Miami groups were similar in language and culture to the Illiniwek tribes.

Around the early 1700s, the Miami began to move back to their original lands in Indiana and Ohio. French traders from Canada helped them by providing firearms. At this time, the main groups of the Miami included:

- Atchakangouen (or Crane Band): This was the largest Miami group. Their main village was Kekionga (Kiihkayonki), located where the Saint Joseph, Saint Marys, and Maumee Rivers meet in Indiana. Kekionga was also the capital of the Miami confederacy.

- Kilatika (or Eel River Band): Their main village was Kineepikwameekwa ("Snake-Fish-Town") along the Eel River in northern Indiana.

- Pepikokia (or Tippecanoe Band): Their main village, Kithtippecanuck, was along the Tippecanoe River.

- Piankeshaw: These people lived in villages along the White River in western Indiana and the Vermilion River in Illinois.

- Wea: Their main village, Waayaahtanonki, was along the Wabash River.

In 1696, the French leader Comte de Frontenac put Jean Baptiste Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes in charge of French outposts in Indiana and Michigan. Vincennes became friends with the Miami people. He set up a trading post and fort at Kekionga (today's Fort Wayne, Indiana) in 1704. This location was very important because it controlled a land route connecting the Maumee River to the Wabash River.

After the French and Indian War, the British took control of the area. This meant more British people came into Miami lands.

Miami and the United States

The Miami had a complicated relationship with the United States. Some Piankeshaw villages supported the American colonists during the American Revolution. However, Miami villages around Ouiatenon were against the Americans. The Miami of Kekionga were allies of the British.

After the American Revolution, the Treaty of Paris in 1783 gave the United States control over the Northwest Territory. This area included modern-day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. White settlers began moving into the Ohio Valley. This led to conflicts because the tribes saw this land as their own. The Miami invited other tribes, like the Delaware and Shawnee, to settle at Kekionga. Together, they formed the Western Confederacy. They fought against the white settlers to protect their lands. This conflict became known as the Northwest Indian War.

In 1790, the U.S. government ordered an attack on Kekionga. American forces destroyed the village, but Miami warriors fought back. In 1791, another American attack led by Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson captured Miami prisoners, including a daughter of Chief Little Turtle. This raid made the tribes even more determined to fight. Later in 1791, a large American army tried to attack Kekionga again, but the Western Confederacy defeated them. This battle, known as St. Clair's Defeat, was a major loss for the U.S. army.

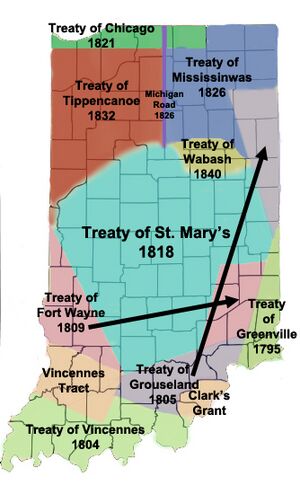

In 1794, a third American force, led by General "Mad" Anthony Wayne, defeated the confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Wayne's forces burned tribal settlements and built Fort Wayne at Kekionga. In 1795, the Treaty of Greenville ended the war. Under this treaty, tribal leaders like Little Turtle agreed to give up most of what is now Ohio, along with other areas like Detroit, Chicago, and Fort Wayne. In return, they received annual payments.

Some Miami people who still resisted the United States gathered around Ouiatenon. There, Shawnee Chief Tecumseh led a new group of Native American nations. In 1811, Governor William Henry Harrison and his forces destroyed Tecumseh's village. During the War of 1812, American forces attacked Miami villages throughout Indiana.

Even though the Treaty of Greenville promised that the remaining tribal land would be theirs forever, this did not happen. White traders often gave the Miami alcohol and goods on credit. The tribes ended up owing more money than their annual payments could cover. U.S. officials used these debts to pressure tribal leaders into signing new treaties. These treaties forced the Miami to give up large parts of their land. As a reward, some chiefs received private land deeds and other benefits. For example, one chief, Jean Baptiste de Richardville, received money to build a mansion.

In 1846, the U.S. government forced most of the Miami tribe to leave Indiana. They were moved first to Kansas, then to Oklahoma. However, some Miami families who owned private property were allowed to stay in Indiana. This caused a deep split within the tribe. In Oklahoma, the Miami were given individual plots of land instead of a reservation. This was part of an effort to make them adopt American ways of life. The U.S. government has recognized the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma as the official tribal government since 1846.

In the 1900s, the Miami in Indiana tried to get separate federal recognition, but they were not successful. Today, the Oklahoma-based Miami tribe has about 5,600 members. Many Indiana-based Miami still feel they are a separate group that should have federal recognition.

Places Named for the Miami

Many places are named after the Miami nation. However, Miami, Florida is not named after this tribe. It is named after the Miami River in Florida, which was named after the unrelated Mayaimi people.

Towns and Cities

CountiesForts

|

Bodies of Water and Geographical Locations

InstitutionsSports Teams

|

Notable Miami People

- Memeskia (Old Briton) (c. 1695–1752), a Miami chief.

- Francis Godfroy (Palawonza) (1788–1840), another Miami Chief.

- Tetinchoua, a powerful Miami chief from the 1600s.

- Little Turtle (Mishikinakwa) (c. 1747–1812), a famous war chief from the 1700s.

- Pacanne (c. 1737–1816), an 18th-century chief.

- Francis La Fontaine (1810–1847), the last main chief of the united Miami tribe.

- Jean Baptiste de Richardville (Peshewa) (c. 1761–1841), a 19th-century chief.

- Frances Slocum (Maconaquah) (1773–1847), a woman adopted into the Miami tribe.

- William Wells (Apekonit), also an adopted member of the Miami tribe.

- Daryl Baldwin (Kinwalaniihsia), recognized for his work in bringing back the Miami language and culture at Miami University.

Images for kids

-

The grave of Miami Chief Francis Godfroy in Miami County, Indiana.

See also

In Spanish: Miami (pueblo amerindio) para niños

In Spanish: Miami (pueblo amerindio) para niños