Science in classical antiquity facts for kids

Science in ancient times means how people in the past tried to understand the world. This included finding ways to solve problems, like making a good calendar or finding cures for sickness. It also involved deep thinking about nature, which was called "natural philosophy."

The "classical antiquity" period lasted a very long time, from about 800 BC to 600 AD. During this time, people's ideas about nature included myths, religion, and early science. The first "scientists" might have seen themselves as thinkers about nature, skilled doctors, or religious healers. Some famous people from this time were Hippocrates, Aristotle, Euclid, Archimedes, Galen, and Ptolemy. Their ideas spread and helped lead to modern science. They studied many things, like mathematics, how the universe works, medicine, and physics.

Contents

Ancient Greece: Seeking Answers

Understanding Why Things Happen

People in ancient Greece first started studying nature to solve everyday problems. For example, they needed a way to keep track of time. Around 700 BC, a poet named Hesiod wrote about a calendar. His calendar used the stars and the Moon's phases to know when to do seasonal tasks. Later, around 450 BC, people made lists of when stars appeared or disappeared. These lists helped Greek cities set their calendars based on what they saw in the sky.

Medicine was another important area. In ancient Greece, there wasn't just one type of doctor. Many different people claimed to be healers, like those following Hippocrates, temple healers, and even gymnastic trainers. They all competed for patients. This competition led to many public discussions about what caused diseases and how to treat them.

For example, a Hippocratic book called On the Sacred Disease talks about epilepsy. The author argued that epilepsy had a natural cause, not a divine one (like being cursed by gods). Even though the author didn't have all the answers, this shows how people started looking for natural explanations for illnesses. People like Aristotle and Theophrastus also studied animals and plants to understand their causes. Theophrastus even tried to classify minerals and rocks, which was a very early step in geology.

Greek science made big steps in learning facts about animals, plants, minerals, and stars. People also started to understand the importance of finding causes for changes and using math to explain nature.

Early Greek Thinkers: The Pre-Socratics

Materialist Philosophers: What is Everything Made Of?

The very first Greek philosophers, called the pre-Socratics, were "materialists." They tried to answer a big question: "How did our ordered universe come to be?" Unlike myths, their answers focused on what things were made of.

Thales (around 600 BC) thought everything came from water. Anaximander (around 600 BC) suggested things came from something he called the "boundless," which was endless and had no specific qualities. Anaximenes (around 500 BC) believed everything came from air, which could change by getting thinner or thicker.

Heraclitus (around 500 BC) thought that change itself was the most important thing, with fire playing a key role. Later, Empedocles (around 400 BC) combined these ideas. He said there were four elements: Earth, Water, Air, and Fire. These elements mixed and separated because of two forces he called Love and Strife.

All these ideas suggested that matter was continuous. But then, Leucippus and Democritus (around 400 BC) came up with the idea of atoms. They believed that everything was made of tiny, indivisible particles called atoms, moving in empty space (the void). These different ideas show that early Greek thinkers debated and criticized each other's theories.

Xenophanes (around 500 BC) even noticed fossils of sea creatures on land. He thought that the Earth and sea would mix and turn into mud over time, which was an early idea related to paleontology and geology.

Pythagorean Philosophy: The Power of Numbers

Some thinkers didn't like the idea that the universe just came together randomly. They believed there must be some ordering principle.

The followers of Pythagoras (around 500 BC) thought that numbers were the basic, unchanging things that made up the universe. Some believed matter was made of points arranged in geometric shapes. Others thought the universe was organized by numbers, ratios, and proportions, much like musical scales. For example, Philolaus believed there were ten heavenly bodies because 1+2+3+4 equals 10, a "perfect" number. The Pythagoreans were among the first to use math to explain the order of the universe, which was a huge step for science.

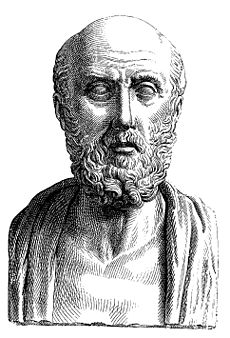

Hippocrates and Medical Writings

Hippocrates of Kos (around 460-370 BC) is often called the "father of medicine." He was known for predicting how diseases would progress, observing patients carefully, and categorizing illnesses. He also developed the idea of humoral theory, which said the body had four main fluids (humors) that needed to be balanced for health. However, many medical writings were later attributed to him, so it's hard to know exactly what he wrote or did.

Even so, the writings linked to Hippocrates greatly influenced medicine in the Islamic world and Europe for over a thousand years.

Schools of Thought: Learning and Debating

Plato's Academy: Ideas and Math

The first major learning center in ancient Greece was founded by Plato (around 427–347 BC). He believed that the universe was ordered by numbers and geometry. It's said that a sign at his school, the Academy, read: "Let no one ignorant of geometry enter." This shows how important math was to Plato.

Plato thought that all physical things were imperfect copies of perfect, unchanging "ideas." Just like a drawing of a circle is never perfect, but the idea of a circle is. Because he believed physical things were imperfect, he thought true knowledge came from thinking and reasoning, like in math, not just from observing the world. He even suggested that astronomy should be studied using abstract math models, not just by looking at the sky.

Aristotle's Lyceum: Observation and Causes

Aristotle (384–322 BC) studied at Plato's Academy but had different ideas. He agreed that truth should be eternal, but he believed we learn about the world through our senses and experience. For Aristotle, real things were what we could observe. Ideas, or "forms," existed within matter, like the "form" of a tree exists in a real tree.

Aristotle's view led to a different way of doing science. He focused on observing physical things. He also thought math was less important for studying nature than Plato did. Aristotle was very interested in how things change. He also identified four causes for everything:

- The material cause: What something is made of (like wood for a table).

- The formal cause: The shape or design of something (the idea of a table).

- The efficient cause: The person or thing that made it (the carpenter).

- The final cause: The purpose for which it was made (to eat on).

Aristotle believed that true scientific knowledge meant knowing these necessary causes. He especially focused on the final cause, or purpose. He saw this in biology, noting that animal organs serve specific functions.

After Plato died, Aristotle started his own school, the Lyceum. He wrote and taught about many scientific topics, including biology, weather, how the mind works, and physics. He developed a theory of physics based on five elements: earth, water, fire, air, and aether. He thought heavy elements (earth and water) naturally moved towards the center of the universe, forming a spherical Earth. Light elements (fire and air) moved away. Since planets and stars moved in circles, he thought they were made of a fifth element, aether.

Aristotle used everyday observations to support his ideas, like a stone falling or flames rising. He also believed that objects in motion would naturally stop unless something kept them moving, and that empty space (a vacuum) was impossible.

Aristotle's student, Theophrastus, wrote important books describing plants and animals. His work helped create the fields of botany (study of plants) and zoology (study of animals). Theophrastus also described minerals and rocks, even noting that the mineral tourmaline could attract things when heated (now called pyroelectricity). Later, Pliny the Elder used Theophrastus's work in his own Natural History. These early writings were key to the development of mineralogy and geology.

Hellenistic Age: Spreading Knowledge

When Alexander the Great conquered many lands, Greek ideas spread to Egypt, Asia Minor, and Persia. This led to new learning centers in cities like Alexandria.

Hellenistic science was different because Greek ideas mixed with those from other cultures. Also, kings and rulers often supported scientific research. The city of Alexandria became a major science hub in the 3rd century BC. The famous Library and Museum were built there. Unlike Plato's and Aristotle's schools, these places were officially supported by the rulers.

Scholars in this period used earlier Greek ideas, like applying math to nature and collecting lots of data. Some historians believe that true scientific methods were born in the 3rd century BC during this time.

Amazing Technology

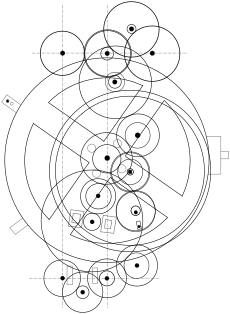

A great example of Hellenistic knowledge and engineering is the Antikythera mechanism (around 150–100 BC). This was a complex mechanical computer with 37 gears! It could calculate the movements of the Sun, Moon, and possibly the five planets known back then. It even predicted eclipses based on knowledge from the Babylonians. This device shows that ancient Greeks had very advanced mechanical skills.

Medical Discoveries

An important medical school developed in Alexandria from the late 300s BC to the 100s BC. Rulers allowed doctors to study human bodies by cutting them open. Herophilos (335–280 BC) and Erasistratus (around 304–250 BC) were pioneers in this. They even performed dissections on criminals who had been sentenced to death.

Herophilos learned a lot about the human body's structure. He showed that the brain, not the heart, was the center of intelligence. He also described the difference between veins and arteries and made many accurate observations about the nervous system. Erasistratus figured out the difference between sensory nerves (for feeling) and motor nerves (for movement) and linked them to the brain. He also described the cerebrum and cerebellum parts of the brain. Because of their work, Herophilos is called the "father of anatomy" and Erasistratus the "founder of physiology."

Advanced Mathematics

Greek mathematics in the Hellenistic period became very advanced. There's also proof that they combined math with great technical skills, like in building huge structures or when Eratosthenes (276–195 BC) measured the distance between the Sun and Earth and the size of the Earth.

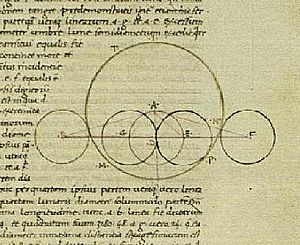

Even though there weren't many Hellenistic mathematicians, they shared their work. Euclid (325–265 BC) wrote the Elements, a series of books on geometry and number theory. This book was the main textbook for math for many centuries, even into the 1900s.

Archimedes (287–212 BC), from Sicily, wrote many important papers. He found the sum of an infinite series, estimated the value of pi (π), and created a way to write very large numbers.

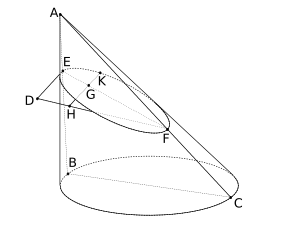

The study of conic sections (shapes like circles, ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas) was a key part of Greek math, mostly developed by Apollonius (262–190 BC).

Astronomy: Looking at the Stars

Mathematical astronomy also made progress. Aristarchus of Samos (310–230 BC) was an astronomer who proposed the first known heliocentric model. This means he thought the Sun was at the center of the universe, with the Earth revolving around it once a year and spinning on its axis once a day. He also estimated the sizes and distances of the Sun and Moon. His idea didn't become popular back then, but it influenced later astronomers like Nicolaus Copernicus.

In the 2nd century BC, Hipparchus discovered precession (a slow wobble of Earth's axis), calculated the Moon's size and distance, and invented early astronomical tools like the astrolabe. Hipparchus also made a detailed catalog of 1020 stars. Many of the constellations we know today come from Greek astronomy.

Roman Era: Organizing Knowledge

Science during the Roman Empire focused on organizing the knowledge gained from the Hellenistic period and the lands the Romans conquered. The works of Roman authors were important because they were passed down to later civilizations.

Even though the Romans ruled, advanced scientific research and teaching mostly continued in Greek. Many Greek and Hellenistic works were kept and developed in the Byzantine Empire and later in the Islamic world. Western Europe only got direct knowledge of most ancient Greek texts much later, starting in the 1100s.

Pliny the Elder: A Natural Historian

Pliny the Elder published his Naturalis Historia in 77 AD. This was a huge collection of information about the natural world that survived into the Middle Ages. Pliny didn't just list things; he also explained phenomena. For example, he correctly described amber as fossilized tree resin, noting insects trapped inside some pieces.

Pliny's work covered plants, animals, and inorganic matter like metals and minerals. He was interested in how humans used (or misused) these things. His descriptions of metals and minerals are very detailed and valuable. Pliny also gave credit to the earlier authors he used, so we know about many lost works from antiquity because he mentioned them. His book was one of the first to be printed in 1489 and became a key reference for scholars for centuries.

Hero of Alexandria: An Inventor

Hero of Alexandria was a Greek-Egyptian mathematician and engineer. He is often seen as the greatest experimenter of ancient times. He invented a windwheel, which was the earliest use of wind power on land. He also described a steam-powered device called an aeolipile, which was the first recorded steam engine.

Galen: A Medical Giant

The most important doctor and philosopher of this era was Galen, active in the 100s AD. About 100 of his works survive, filling 22 modern books! Galen was born in Pergamon (now Turkey). His father, an architect, made sure he got a good education. Galen studied all the major philosophies before his father, inspired by a dream, decided he should study medicine. Galen traveled widely to learn from the best doctors.

Galen collected much of the medical knowledge from earlier times. He also learned more about how organs work by performing dissections on animals like apes, oxen, and pigs. As a chief physician for gladiators, he studied many kinds of wounds. Through his experiments, Galen proved that living arteries contain blood, not air, which was a common belief. However, he mistakenly thought blood flowed back and forth from the heart in a tide-like motion. This idea was accepted for centuries.

Anatomy was a huge part of Galen's medical training and interest. His two main anatomy books became the standard for all doctors for the next 1300 years, until they were challenged in the 1500s.

Ptolemy: Mapping the Cosmos

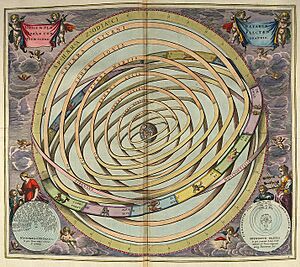

Claudius Ptolemy (around 100–170 AD), who lived near Alexandria, wrote about a dozen books on astronomy, astrology, cartography (map-making), music theory, and optics (light). Many of his complex works have survived. Ptolemy focused on using math to model physical things and visualizing reality.

Ptolemy combined theory with observations. His most famous astronomy book, the Almagest, aimed to improve on earlier works by using strong math and showing how observations fit with theory. In another book, Planetary Hypotheses, he described physical models of his math ideas, probably to help people learn. His Geography focused on drawing accurate maps using astronomical information. His books on music and optics also included instructions on how to build and use instruments to test theories.

Ptolemy was so thorough and good at presenting data (like using many tables) that his work made earlier works on these topics seem outdated. His astronomy work, especially, set the standard for centuries. The Ptolemaic system, which placed Earth at the center of the universe, was the main model for how the heavens moved until the 1600s.

See also

In Spanish: Ciencia en la Edad Antigua para niños

In Spanish: Ciencia en la Edad Antigua para niños

- Ancient Greek technology

- Ancient Greek geography

- Protoscience

- Roman technology

- Obsolete scientific theories

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |