Billy Sunday facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Billy Sunday

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

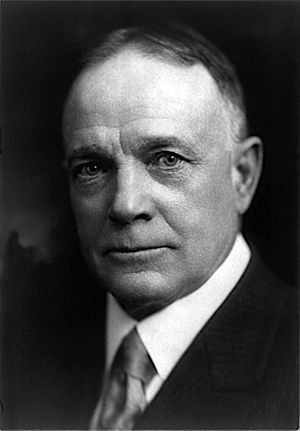

Billy Sunday (1921)

|

|||

| Born |

William Ashley Sunday

November 19, 1862 Story County, Iowa, U.S.

|

||

| Died | November 6, 1935 (aged 72) |

||

| Resting place | Forest Home Cemetery, Forest Park, Illinois | ||

| Occupation | Baseball player Christian evangelist |

||

| Spouse(s) | Helen Thompson Sunday | ||

| Children | 4 | ||

|

Baseball career |

|||

|

|||

| Outfielder | |||

|

|||

| debut | |||

| May 22, 1883, for the Chicago White Stockings | |||

| Last appearance | |||

| October 4, 1890, for the Philadelphia Phillies | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .248 | ||

| Home runs | 12 | ||

| Runs batted in | 170 | ||

| Stolen bases | 246 | ||

| Teams | |||

|

|||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

|

|||

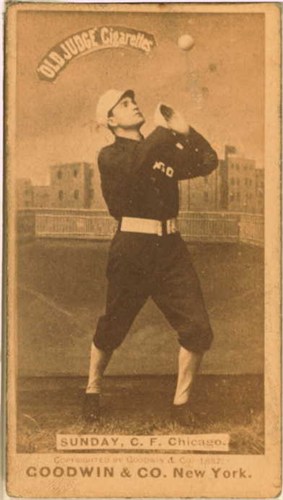

William Ashley "Billy" Sunday (November 19, 1862 – November 6, 1935) was an American outfielder in baseball's National League. He became one of the most famous Christian evangelists in the early 1900s.

Billy Sunday was born into a poor family in Iowa. He spent some years in an orphanage before working odd jobs. He also played for local running and baseball teams. His amazing speed and quickness helped him play baseball in the major leagues for eight years. He was an average hitter but a very good fielder known for his fast base-running.

In the 1880s, Sunday became a Christian. He then left baseball to work in Christian ministry. He slowly became a skilled preacher in the Midwest. In the early 1900s, he became the most famous evangelist in the country. He was known for his everyday language in sermons and his energetic way of speaking. Sunday held large events in America's biggest cities. He drew bigger crowds than any evangelist before electronic sound systems existed. He also earned a lot of money and was welcomed by rich and powerful people. Sunday strongly supported Prohibition, which banned alcohol. His speeches likely helped pass the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919.

Even though people wondered about his money, Billy Sunday never faced any scandals. He was truly devoted to his wife, Helen, who also managed his campaigns. His audiences became smaller in the 1920s as he got older. Also, religious events became less popular, and new forms of entertainment appeared. Still, Sunday continued to preach and share his Christian beliefs until he passed away.

Contents

Early Life and Childhood

Billy Sunday was born near Ames, Iowa. His father, William Sunday, was from a German family. They changed their name from "Sonntag" to "Sunday" when they moved to Pennsylvania. William Sunday was a bricklayer who came to Iowa. There, he married Mary Jane Corey. Her father was a local farmer, miller, blacksmith, and wheelwright.

William Sunday joined the army on August 14, 1862. He died four months later from an illness at an army camp. This happened five weeks after Billy was born. Mary Jane Sunday and her children then lived with her parents for a few years. Young Billy grew very close to his grandparents. Mary Jane Sunday later remarried, but her second husband soon left the family.

When Billy Sunday was ten, his mother, who was very poor, sent him and his older brother to an orphanage. First, they went to the Soldiers' Orphans Home in Glenwood, Iowa. Later, they moved to the Iowa Soldiers' Orphans' Home in Davenport, Iowa. At the orphanage, Sunday learned good habits and received a basic education. He also realized he was a talented athlete.

By age fourteen, Sunday was living on his own. In Nevada, Iowa, he worked for Colonel John Scott, a former lieutenant governor. Billy took care of Shetland ponies and did other farm chores. The Scotts gave Sunday a good home and a chance to attend Nevada High School. Even though Sunday never finished high school, by 1880, he had a better education than many people his age.

In 1880, Sunday moved to Marshalltown, Iowa. He was recruited to join a fire brigade team because of his athletic skills. In Marshalltown, Sunday worked various odd jobs. He also competed in fire brigade tournaments and played for the town's baseball team.

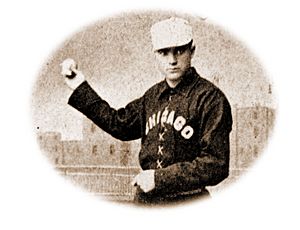

Professional Baseball Career

Billy Sunday's professional baseball career began thanks to Cap Anson. Anson was from Marshalltown and would later become a Hall of Famer. His aunt, who loved the Marshalltown team, told him how good Sunday was. In 1883, Anson suggested Sunday to A.G. Spalding, the president of the Chicago White Stockings. Sunday was then signed to the team, who were the defending National League champions.

In his first game, Sunday struck out four times. It took him three more games and seven more strikeouts to get his first hit. For his first four seasons with Chicago, he was a part-time player. He played right field when Mike "King" Kelly was playing catcher.

Sunday's best skill was his speed. He used it both when running bases and in the outfield. In 1885, the White Stockings set up a race between Sunday and Arlie Latham. Latham was known as the fastest runner in the American Association. Sunday won the hundred-yard dash by about ten feet.

Fans and teammates liked Sunday because of his personality and athletic ability. Manager Cap Anson trusted Sunday enough to make him the team's business manager. This job included handling ticket money and paying for the team's travel.

In 1887, when Kelly was sold to another team, Sunday became Chicago's regular right fielder. However, an injury limited him to playing only fifty games. The next winter, Sunday was sold to the Pittsburgh Alleghenys for the 1888 season. He became their starting center fielder, playing a full season for the first time. The fans in Pittsburgh immediately loved Sunday. One reporter wrote that "the whole town is wild over Sunday." Even though Pittsburgh had losing teams in 1888 and 1889, Sunday played well in center field. He was among the league leaders in stolen bases.

In 1890, a disagreement among players led to a new league being formed. Most of the best players from the National League joined it. Sunday was asked to join the new league. However, his beliefs would not let him break his contract. The "reserve clause" allowed Pittsburgh to keep the rights to Sunday even after his contract ended. Sunday was made team captain and was their star player. But the team had one of the worst seasons in baseball history. By August, the team had no money to pay its players. Sunday was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for two players and $1,000.

The Philadelphia team had a chance to win the National League pennant. The owners hoped that adding Sunday would improve their chances. Sunday played well in his thirty-one games with Philadelphia. However, the team finished in third place.

In March 1891, Sunday asked to be released from his contract with the Philadelphia team, and it was granted. Throughout his career, Sunday was not a great hitter. His batting average was .248 over 499 games. This was about average for the 1880s. In his best season, in 1887, Sunday hit .291, ranking 17th in the league. He was an exciting but sometimes inconsistent fielder. In the days before outfielders wore gloves, Sunday was known for thrilling catches. These included long sprints and athletic dives. But he also made many errors. Sunday was best known as an exciting base-runner. His peers thought he was one of the fastest in the game. However, he never ranked higher than third in the National League in stolen bases.

Sunday remained a big baseball fan throughout his life. He gave interviews and shared his thoughts about baseball with the media. He often umpired minor league and amateur games in the cities where he held his religious events. He also went to baseball games whenever he could. This included a 1935 World Series game just two months before he died.

Becoming an Evangelist

One Sunday afternoon in Chicago, during the 1886 or 1887 baseball season, Sunday and some teammates were out on their day off. They stopped to listen to a group preaching from the Pacific Garden Mission. Sunday was drawn to the hymns, which reminded him of songs his mother sang. He started going to services at the mission. After talking with a woman who worked there, Sunday decided to become a Christian. He began attending the Jefferson Park Presbyterian Church. This church was close to both the baseball park and his rented room.

After his conversion, Sunday stopped drinking, swearing, and gambling. He changed his behavior, and his teammates and fans noticed. Soon after, Sunday began speaking in churches and at YMCAs.

Marriage and Ministry Training

In 1886, Sunday met Helen Amelia "Nell" Thompson at Jefferson Park Presbyterian Church. She was the daughter of a wealthy dairy business owner in Chicago. Sunday was immediately smitten with her. However, both had other serious relationships. Also, Nell came from a much richer background than Sunday. Her father strongly disliked the idea of them dating. He thought all professional baseball players were "unstable and would be misfits once they were too old to play."

Despite this, Sunday pursued Nell and eventually married her. Sunday often said, "She was a Presbyterian, so I am a Presbyterian. Had she been a Catholic, I would have been a Catholic—because I was hot on the trail of Nell." Her mother liked Sunday from the start and supported him. Her father finally agreed. The couple married on September 5, 1888.

In the spring of 1891, Sunday turned down a baseball contract worth $3,500 a year. Instead, he took a job with the Chicago YMCA for $83 a month. Sunday's job title was Assistant Secretary, but it involved a lot of ministry work. This proved to be great training for his future as an evangelist. For three years, Sunday visited sick people, prayed with those in trouble, and went to saloons to invite people to religious meetings.

In 1893, Sunday became the full-time assistant to J. Wilbur Chapman. Chapman was one of the most famous evangelists in the United States at that time. Chapman was well-educated and always dressed neatly. He was a bit shy, like Sunday, but he earned respect when he preached because of his strong voice and refined manner. Sunday's job was to go ahead of Chapman to cities where he was scheduled to preach. He would organize prayer meetings and choirs and handle other important details. When tents were used, Sunday often helped set them up.

By listening to Chapman preach night after night, Sunday learned a lot about giving sermons. Chapman also gave Sunday feedback on his own attempts at preaching. He showed him how to put a good sermon together. Chapman also encouraged Sunday's religious growth. He stressed the importance of prayer and helped strengthen Billy's commitment to traditional Christian beliefs.

A Popular Evangelist Emerges

The Kerosene Circuit

When Chapman unexpectedly returned to being a pastor in 1896, Sunday started his own ministry. He began with meetings in small towns like Garner, Iowa. For the next twelve years, Sunday preached in about seventy communities. Most of these were in Iowa and Illinois. Sunday called these towns the "kerosene circuit." This was because, unlike Chicago, most of them did not yet have electricity. Towns often booked Sunday's meetings informally. Sometimes, a group would go to hear him preach and then send him a telegram while he was speaking somewhere else.

Sunday also used his fame as a baseball player to advertise his meetings. In 1907, in Fairfield, Iowa, Sunday organized local businesses into two baseball teams. He then scheduled a game between them. Sunday came dressed in his professional uniform and played on both sides. While baseball was his main way to get attention, Sunday once hired a circus giant to work as an usher.

When Sunday started attracting crowds too large for rural churches or town halls, he rented canvas tents. Again, Sunday did much of the hard work of setting them up. He would handle ropes during storms and sleep in the tents at night to keep them safe. It wasn't until 1905 that he was wealthy enough to hire his own advance man.

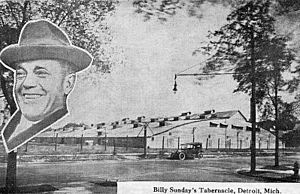

In 1906, a snowstorm in Salida, Colorado, destroyed Sunday's tent. This was a big problem because revivalists were usually paid with a donation at the end of their meetings. After this, he insisted that towns build him temporary wooden buildings called tabernacles at their own expense. These tabernacles were quite expensive to build. However, most of the wood could be saved and sold after the meetings. Local people had to pay for them in advance. This change started to make the money side of Sunday's campaigns more important. At first, building the tabernacles created good public relations. Townspeople worked together in what was like a giant barn-raising. Sunday built good relationships by helping with the process. The tabernacles were also a sign of importance, as they had only been built for major evangelists like Chapman before.

Nell Sunday's Management

After eleven years of Sunday's evangelistic career, both he and his wife were very tired. Being apart for long periods made him feel more inadequate and insecure. Because of his difficult childhood, he relied heavily on his wife's love and support. For her part, Nell found it harder and harder to manage the household, care for four children (including a newborn), and support her husband emotionally from a distance. His ministry was also growing, and he needed someone to manage it. His wife was perfect for the job. In 1908, the Sundays decided to hire a nanny for their children so Nell could manage the revival campaigns.

Nell Sunday changed her husband's informal organization into a "nationally famous event." New staff members were hired. By the New York campaign of 1917, the Sundays had twenty-six paid staff members. There were musicians, caretakers, and advance men. The Sundays also hired Bible teachers, both men and women. These teachers held daytime meetings at schools and shops. They encouraged their audiences to attend the main tabernacle services in the evenings. The most important new staff members were Homer Rodeheaver and Virginia Healey Asher. Rodeheaver was an amazing song leader and music director who worked with the Sundays for almost twenty years starting in 1910. Asher directed the women's ministries, especially reaching out to young working women. She also regularly sang duets with Rodeheaver.

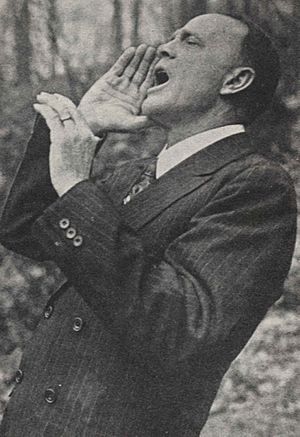

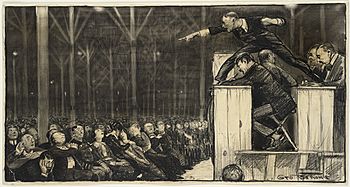

Preaching Style and Impact

With his wife managing the campaigns, Sunday was free to do what he did best: create and deliver his everyday sermons. Usually, Homer Rodeheaver would first get the crowd excited with group singing. This would switch with songs from huge choirs and music played by the staff. When Sunday felt the time was right, he would start his message. Sunday would twist, stand on the pulpit, run from one end of the stage to the other, and dive across the stage, pretending to slide into home plate. Sometimes he even broke chairs to make his points stronger. His sermon notes had to be printed in large letters so he could quickly see them as he ran past the pulpit.

Homer Rodeheaver said that "One of these sermons, until he tempered it down a little, had one ten-minute period in it where from two to twelve men fainted and had to be carried out every time I heard him preach it." Some religious and social leaders criticized Sunday's exaggerated movements. They also disliked the slang and everyday words he used in his sermons. However, audiences clearly enjoyed them.

In 1907, journalist Lindsay Denison wrote that Sunday preached "the old, old doctrine of damnation." Denison said, "In spite of his conviction that the truly religious man should take his religion joyfully, he gets his results by inspiring fear and gloom in the hearts of sinners." He added that Sunday used "the fear of death, with torment beyond it" to make people change. But Sunday himself told reporters that his revivals had "no emotionalism." Caricatures compared him to the wildness of mid-1800s camp meetings. Sunday told one reporter that he believed people could "be converted without any fuss." At Sunday's meetings, there were "few instances of spasm, shakes, or fainting fits caused by hysteria."

Crowd noise, especially coughing and crying babies, made it hard for Sunday to preach. This was because the wooden tabernacles had very lively acoustics. Before the main event, Rodeheaver often told audiences how to quiet their coughs. Nurseries were always provided, and babies were not allowed in the main hall. Sunday sometimes seemed rude in his hurry to remove noisy children who had gotten past the ushers.

Tabernacle floors were covered with sawdust. This was to quiet the sound of shuffling feet. It also smelled nice and kept dust down on dirt floors. Walking to the front when the preacher invited people became known as "hitting the sawdust trail." This term was first used in a Sunday campaign in Bellingham, Washington, in 1910. It seems "hitting the sawdust trail" was first used by loggers in the Pacific Northwest. It meant following a path of sawdust through an uncut forest to get home. Nell Sunday described it as a way of coming from "a lost condition to a saved condition."

By 1910, Sunday began holding meetings (usually longer than a month) in smaller cities. These included Youngstown, Wilkes-Barre, South Bend, and Denver. Then, between 1915 and 1917, he held events in major cities like Philadelphia, Syracuse, Kansas City, Detroit, Boston, Buffalo, and New York City. During the 1910s, Sunday was front-page news in the cities where he held campaigns. Newspapers often printed his sermons completely. During World War I, local news coverage of his campaigns was often bigger than that of the war. Sunday was the subject of over sixty articles in major magazines. He was also a regular topic in religious newspapers, no matter the denomination.

Throughout his career, Sunday likely preached to over one hundred million people face-to-face. For most of them, there was no electronic sound system. Huge numbers of people "hit the sawdust trail." While the usual total given for those who came forward is one million, one modern historian estimates the real number is closer to 1,250,000. Sunday did not preach to a hundred million different people. Instead, many of the same people came repeatedly during a campaign. Before he died, Sunday estimated he had preached nearly 20,000 sermons. This is an average of 42 per month from 1896 to 1935. During his most popular time, when he preached more than twenty times each week, his crowds were often enormous. Even in 1923, when his popularity was declining, 479,300 people attended 79 meetings during the six-week 1923 Columbia, South Carolina, campaign. This was 23 times the white population of Columbia. However, "trail hitters" were not always new Christians. Sometimes, whole groups of club members came forward together at Sunday's urging. By 1927, Rodeheaver was complaining that Sunday's invitations had become so general that they didn't mean much.

Success and Lifestyle

Large crowds and a well-run organization meant that Sunday, who had grown up in an orphanage, soon earned a lot of money. Questions about Sunday's income first came up during the Columbus, Ohio, campaign in late 1912 and early 1913. During the Pittsburgh campaign a year later, Sunday spoke four times a day. He effectively made $217 per sermon, or $870 a day. At that time, the average worker earned $836 per year. The major cities of Chicago, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, and New York City gave Sunday even larger donations. Sunday gave Chicago's donation of $58,000 to Pacific Garden Mission. He gave the $120,500 New York donation to war charities. Still, between 1908 and 1920, the Sundays earned over a million dollars. An average worker during the same time earned less than $14,000.

Sunday was welcomed by important people in society, business, and politics. He knew several famous businessmen. Sunday ate meals with many politicians, including Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. He was also friends with Herbert Hoover and John D. Rockefeller, Jr.. During and after the 1917 Los Angeles campaign, the Sundays visited Hollywood stars. Members of Sunday's organization played a charity baseball game against a team of show business people, including Douglas Fairbanks, Sr.

The Sundays enjoyed dressing well and dressing their children well. The family wore expensive but tasteful coats, boots, and jewelry. Nell Sunday also bought land as an investment. In 1909, the Sundays bought an apple orchard in Hood River, Oregon. They vacationed there for several years. Although the property only had a simple cabin, reporters called it a "ranch." Sunday was generous with money and gave away much of his earnings. Neither of the Sundays spent money extravagantly. Although Sunday enjoyed driving, the couple never owned a car. In 1911, the Sundays moved to Winona Lake, Indiana. They built an American Craftsman-style house, which they called "Mount Hood." This was probably a reminder of their Oregon vacation cabin. The house, furnished in the popular Arts and Crafts style, had two porches and a terraced garden. But it had only nine rooms and about 2,500 square feet (230 m2) of living space, and no garage.

Religious and Social Views

Sunday was a traditional evangelical who believed in fundamentalist teachings. He believed and preached that the Bible was without error. He also believed in the virgin birth of Jesus, that Jesus died for people's sins, and that Jesus physically rose from the dead. He believed in a real devil and hell, and that Jesus Christ would return soon. In the early 1900s, most Protestant church members, no matter their denomination, agreed with these beliefs. Sunday refused to hold meetings in cities where he was not welcomed by most Protestant churches and their leaders.

Sunday was not someone who separated himself from other Christians, as many Protestants of his time were. He made an effort to avoid criticizing the Roman Catholic Church. He even met with Cardinal Gibbons during his 1916 Baltimore campaign. Also, cards filled out by "trail hitters" were faithfully sent to the church or denomination the writers chose. This included Catholic and Unitarian churches.

Although Sunday was ordained by the Presbyterian Church in 1903, his ministry was open to all denominations. He was not a strict Calvinist. He preached that people were, at least in part, responsible for their own salvation. "Trail hitters" received a four-page paper that said, "if you have done your part (i.e. believe that Christ died in your place, and receive Him as your Saviour and Master) God has done HIS part and imparted to you His own nature."

Sunday never went to seminary (a school for religious studies). He did not pretend to be a theologian or an intellectual. However, he knew the Bible very well and read a lot about religious and social issues of his time. His library in Winona Lake, with six hundred books, shows heavy use. There are underlines and notes in his unique all-caps writing. Some of Sunday's books were even from religious opponents. He was once accused of copying a Decoration Day speech given by the famous agnostic Robert Ingersoll.

Sunday's simple preaching style appealed widely to his audiences. They were "entertained, scolded, encouraged, and amazed." Sunday claimed to be "an old-fashioned preacher of the old-time religion." His straightforward sermons spoke of a personal God, salvation through Jesus Christ, and following the moral lessons of the Bible. Sunday's beliefs, though sometimes called too simple, were common among Protestants of his era.

Views on Society and Politics

Sunday was a lifelong Republican. He held common political and social views from his home in the Midwest. These included believing in individual effort, competition, self-control, and being against too much government control. Writers like Sinclair Lewis, Henry M. Tichenor, and John Reed criticized Sunday, saying he was used by big businesses. Poet Carl Sandburg called him a "four-flusher" and a "bunkshooter." However, Sunday agreed with Progressives on some issues. For example, he spoke out against child labor and supported urban improvements and women's suffrage. Sunday criticized business owners "whose private lives are good, but whose public lives are very bad." He also spoke against those "who would not pick the pockets of one man with the fingers of their hand" but who would "without hesitation pick the pockets of eighty million people with fingers of their monopoly or commercial advantage." Even though he always felt sympathy for the poor and tried to bridge differences between races during the time of Jim Crow laws, Sunday did receive donations from members of the Second Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. For instance, in 1927, in Bangor, Maine, Sunday's music director, Homer Rodeheaver, told Klansmen who briefly interrupted the service that "he did not believe that any organization that marched behind the Cross of Christ and the American Flag could be anything but a power for good."

Sunday was a strong supporter of World War I. In 1918, he said, "I tell you it is [Kaiser] Bill against Woodrow, Germany against America, Hell against Heaven." Sunday raised a lot of money for the troops, sold war bonds, and encouraged people to join the military.

Sunday had been a passionate supporter of the temperance movement (which aimed to reduce or stop alcohol use) from his earliest days as an evangelist. Sunday's most famous sermon was "Get on the Water Wagon." He preached it many times with dramatic emotion and a "mountain of economic and moral evidence." Sunday said, "I am the sworn, eternal and uncompromising enemy of the Liquor Traffic. I have been, and will go on, fighting that damnable, dirty, rotten business with all the power at my command." Sunday played a big part in getting public interest in Prohibition and in the passing of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919. When public opinion turned against Prohibition, he continued to support it. After it was repealed in 1933, Sunday called for it to be brought back.

Sunday also opposed eugenics (a belief in improving the human race by controlling who can have children). He also opposed recent immigration from southern and eastern Europe. He was against the teaching of evolution. Furthermore, he criticized popular middle-class pastimes like dancing, playing cards, going to the theater, and reading novels. However, he believed baseball was a healthy and even patriotic form of recreation, as long as it was not played on Sundays.

Later Years and Death

Sunday's popularity decreased after World War I. Many people in his audiences were drawn to radio shows and movies instead. The Sundays' health also declined, even as they continued to push themselves through many revivals. These later revivals were smaller and had fewer staff members to help them.

Sad events marked Sunday's final years. His three sons faced many challenges. In 1930, Nora Lynn, their housekeeper and nanny, who had become like family, passed away. Then, the Sundays' daughter, the only child actually raised by Nell, died in 1932 from what seemed to be multiple sclerosis. Their oldest son, George, who his parents had saved from financial trouble, died in 1933.

Even though the crowds got smaller during the last 15 years of his life, Sunday kept accepting invitations to preach. He continued to speak effectively. In early 1935, he had a mild heart attack. His doctor told him to stop preaching. Sunday did not follow this advice. He died on November 6, a week after giving his last sermon on the topic "What must I do to be saved?"

Images for kids