History of Cyprus facts for kids

Cyprus is an island with a very long history of people living there. Humans first arrived in Cyprus during the Stone Age. Because of its special location in the Eastern Mediterranean, the island has been shaped by many different civilizations over thousands of years.

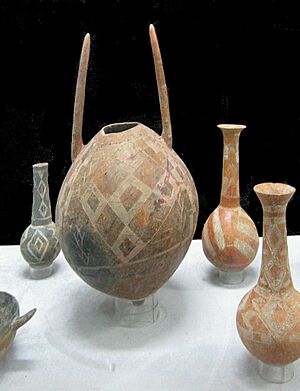

Historians often name periods of Cyprus's history after 1050 BC based on the styles of pottery found. Here are some of these periods:

- Cypro-Geometric I: 1050–950 BC

- Cypro-Geometric II: 950–900 BC

- Cypro-Geometric III: 900–750 BC

- Cypro-Archaic I: 750–600 BC

- Cypro-Archaic II: 600–480 BC

- Cypro-Classical I: 480–400 BC

- Cypro-Classical II: 400–310 BC

Contents

Ancient Life: Prehistoric Cyprus

Before humans came to Cyprus, only a few types of land mammals lived there. These included the Cypriot pygmy hippopotamus and the Cyprus dwarf elephant. These animals were much smaller than their relatives on the mainland. This happened because they lived on an island, a process called insular dwarfism (where animals become smaller over generations on islands). Other animals were the genet Genetta plesictoides and the Cypriot mouse, which still lives today.

The first humans arrived in Cyprus about 13,000 to 12,000 years ago. They were hunter-gatherers, meaning they hunted animals and gathered plants for food. The dwarf hippos and elephants disappeared shortly after humans settled. The hunter-gatherers later brought wild boar to the island, probably as a food source.

Around 8,500 BC, the first Neolithic farming settlements appeared. People started bringing animals like dogs, sheep, goats, and possibly cattle. They also introduced wild animals like foxes and Persian fallow deer. These animals were new to the island. Early settlers built round houses with floors made of a special material called terrazzo. They grew crops like einkorn and emmer.

In the 6th millennium BC, the Khirokitia culture was known for its round houses and stone tools. Their economy relied on sheep, goats, and pigs. They also hunted Persian fallow deer. This culture was followed by the Sotira phase, which used pottery. The Eneolithic era is known for stone figurines with outstretched arms.

Archaeologists have found some of the oldest water wells in the world in western Cyprus. They are 9,000 to 10,500 years old, dating back to the Stone Age. These wells show how clever early settlers were and how much they valued their environment.

In 2004, something amazing was found: the remains of an 8-month-old cat buried with its human owner. This grave is about 9,500 years old. This discovery shows that cats and humans were close much earlier than previously thought, even before Egyptian civilization.

Bronze Age: Cities and Copper Trade

During the Bronze Age, the first cities began to appear in Cyprus, like Enkomi. People started mining copper in a big way, and this valuable metal was traded far and wide. Mycenaean Greeks were living in Cyprus by the late Bronze Age. The Greek name for the island was already used around 1500 BC.

A special writing system called the Cypro-Minoan syllabic script was used in the early part of the late Bronze Age. It was used for about 500 years. We don't know if older languages survived or if a new language, called Eteocypriot, was brought by people from the East.

The period between 1300–1200 BC was a time of great wealth for Cyprus. Cities like Enkomi were rebuilt with straight streets and large buildings. Important buildings made of large, cut stones (called ashlar masonry) show that society was becoming more organized. Some of these buildings were used to process and store olive oil. Temples were also built in places like Myrtou-Pigadhes, Enkomi, Kition, and Kouklia. The way cities were planned and the new building styles were similar to those in Syria, especially in a city called Ugarit.

Writing became more common, and tablets with the Cypro-Minoan script have been found in Ugarit. Texts from Ugarit and Enkomi mention "Ya," which was the Assyrian name for Cyprus. This shows the name was used even in the late Bronze Age.

Copper bars shaped like ox hides have been found in ancient shipwrecks. This proves that copper was traded widely across the sea. Weights shaped like animals found in Enkomi and Kalavassos show that Cyprus traded with many different regions, including Syria, Mesopotamia, and the Aegean Sea.

Late Bronze Age Cyprus was part of the Hittite Empire. However, it was a client state, meaning it was not directly invaded. Instead, it was linked to the empire and mostly left alone.

Even though Achaean Greeks lived in Cyprus from the 14th century BC, most of them settled on the island after the Trojan War. Achaeans continued to settle in Cyprus from 1210 to 1000 BC. Dorian Greeks arrived around 1100 BC. Unlike what happened on the Greek mainland, it seems they settled peacefully in Cyprus.

Another group of Greek settlers arrived in the following century (1100–1050 BC). This is shown by new types of graves and Greek influences in pottery designs.

Alashiya: The Copper Kingdom

Alashiya was a powerful state in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Bronze Age. It was a major source of copper for the region. Most historians believe Alashiya was located in Cyprus or included parts of the island.

Letters between the King of Alashiya and the rulers of Ancient Egypt have been found. These are known as the Amarna letters. There were also letters between the King of Alashiya and the King of Ugarit.

Pottery Styles

In the later part of the late Bronze Age (1200–1100 BC), a lot of 'Mycenaean' IIIC:1b pottery was made right there in Cyprus. New building styles appeared, like cyclopean walls (large walls made of huge, rough stones), which were also found in mainland Greece. Rectangular stepped capitals, a type of column top, were unique to Cyprus.

Many IIIC:1b pottery pieces have also been found in Palestine during this time. While some once thought this meant an invasion by the 'Sea Peoples', it is now seen more as a local development. This was likely caused by more trade with Cyprus and Crete. Evidence of early trade with Crete includes pottery from Kydonia, an important city in ancient Crete, found in Cyprus.

Cypriot City Kingdoms Emerge

Most historians believe that the Cypriot city kingdoms, first mentioned in writings around 800 BC, actually began in the 11th century BC. Other experts think it was a slower process. They believe that small chiefdoms gradually grew more complex between the 12th and 8th centuries.

In the 8th century BC, during the Geometric period, the number of settlements grew sharply. Grand tombs, like the 'Royal' tombs of Salamis, appeared for the first time. This might be a better sign that the Cypriot kingdoms were truly forming.

Early Iron Age: New Influences

The early Iron Age in Cyprus followed the Submycenaean period (1125–1050 BC) of the Late Bronze Age. It is divided into the Geometric (1050–700 BC) and Archaic (700–525 BC) periods.

Ancient writers tell stories that connect the founding of many Cypriot towns to Greek heroes who came after the Trojan war. For example, Teucer, the brother of Aias, was said to have founded Salamis. Also, Agapenor from Arcadia was believed to have replaced the local ruler Kinyras and founded Paphos. Some scholars think these stories are memories of Greek settlement as early as the 11th century BC.

In an 11th-century tomb at Palaepaphos-Skales, three bronze obeloi (spits) with inscriptions in Cypriot syllabic script were found. One of them had the name Opheltas. This is the first sign of the Greek language being used on the island.

Cremation, the practice of burning the dead, is also seen as a Greek custom brought to Cyprus. The first cremation burial in bronze vessels was found at Kourion-Kaloriziki, dating to the early 11th century. This tomb contained valuable items like bronze tripod stands, a shield, and a golden scepter. The scepter's design, with two falcons, shows a strong Egyptian influence.

A group of people living in Amathus during the early Iron Age left writings in the Eteocypriot language. They used the Cypriot syllabary. We don't know if this language was a continuation of a Bronze Age language spoken in Cyprus or if it was related to other languages like Hurrian.

Phoenicians Arrive

Historical writings suggest that Phoenicians were present in Kition very early, under the rule of Tyre in the 10th century BC. Some Phoenician merchants from Tyre settled in the area and helped Kition grow in power. After about 850 BC, the religious sites in Kition were rebuilt and used by the Phoenicians.

The oldest cemetery in Salamis has children's burials in Canaanite jars. This shows that Phoenicians were present as early as the 11th century BC. Similar jar burials have been found in Kourion-Kaloriziki and Palaepaphos-Skales. Many items from the Levant (the region including Phoenicia) and Cypriot copies of Levantine styles have been found in Skales. This suggests Phoenician influence spread even before the end of the 11th century.

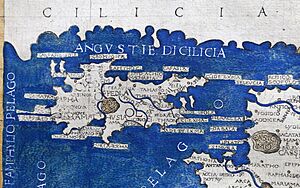

Ancient Cyprus: Empires and Independence

The Assyrians became aware of Cyprus again in the late 8th century BC. However, they did not keep control of the island for long. The Assyrian name for Cyprus, Iadnana, likely meant "island of the Danunians." A stone monument found in Kition celebrates the victory of King Sargon II (721–705 BC) in 709 BC over seven kings in the land of Ia', which was part of Iadnana.

An inscription from Esarhaddon in 673/2 BC lists ten kingdoms in Cyprus. These have been identified as Salamis, Kition, Amathus, Kourion, Paphos, and Soli along the coast. In the island's interior were Tamassos, Ledra, Idalium, and Chytri.

Cyprus gained independence for a short time around 669 BC. But it was then conquered by Egypt under Amasis (570–526/525 BC). The Persians conquered the island around 545 BC. A Persian palace has been found near Soli. The people of Cyprus took part in the Ionian revolt against Persia.

In the early 4th century BC, Euagoras I, the King of Salamis, took control of the entire island. He tried to make Cyprus independent from Persia. Another uprising happened in 350 BC, but it was crushed by Artaxerxes in 344 BC.

During the siege of Tyre, the Cypriot Kings joined forces with Alexander the Great. After Alexander's death, in 321 BC, four Cypriot kings supported Ptolemy I and defended the island against Antigonos. Ptolemy lost Cyprus to Demetrios Poliorketes between 306 and 295 BC. But after that, Cyprus remained under Ptolemaic rule until 58 BC. It was governed by a ruler from Egypt. Sometimes, it even became a smaller Ptolemaic kingdom during power struggles in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. Cyprus developed strong trade links with Athens and Alexandria, two major trade centers of the ancient world.

Cyprus became fully Greek in its culture under Ptolemaic rule. Phoenician customs and the old Cypriot syllabic script disappeared. Several new cities were founded during this time, such as Arsinoe, built by Ptolemy II.

Cyprus became a Roman province in 58 BC. According to Strabo, a Roman writer, this happened because a Roman politician, Publius Clodius Pulcher, held a grudge against the king of Cyprus, Ptolemy of Cyprus. He sent Marcus Cato to conquer the island. Mark Antony later gave the island to Cleopatra VII of Egypt and her sister Arsinoe IV. But after Antony's defeat at the Battle of Actium (31 BC), Cyprus became a Roman province again in 30 BC. From 22 BC, it was a senatorial province, meaning it was governed by the Roman Senate. The island suffered greatly during the Jewish uprising of 115/116 AD.

After the reforms of Diocletian, Cyprus was placed under the control of the Consularis Oriens and governed by a proconsul. Several earthquakes destroyed Salamis in the early 4th century. At the same time, the island faced drought and famine.

Medieval Cyprus: Byzantines, Arabs, and Crusaders

After the Roman Empire split into an eastern and western part, Cyprus came under the rule of the Eastern Roman Empire. At that time, the island's bishop became autocephalous, meaning he could choose his own leader, by the First Council of Ephesus in 431 AD. He was still part of the wider Christian Church.

The Arab Muslims invaded Cyprus in the 650s. But in 688, the Byzantine emperor Justinian II and the Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān made a special agreement. For the next 300 years, Cyprus was ruled jointly by both the Arabs and the Byzantines. This was called a condominium. Even though there was often fighting between the two sides on the mainland, this shared rule in Cyprus continued.

This period lasted until 965 AD, when Niketas Chalkoutzes conquered the island for the Byzantines. In 1185, the last Byzantine governor of Cyprus, Isaac Comnenus of Cyprus, rebelled and tried to take the throne. He failed to become emperor, but he kept control of Cyprus. The Byzantines couldn't defeat him because he had the support of William II of Sicily. The Byzantine emperor had also agreed with the sultan of Egypt to close Cypriot harbors to the Crusaders.

The Third Crusade and Richard the Lionheart

During the Third Crusade, Cyprus became important to the Crusaders in the late 12th century. Richard the Lionheart, the King of England, landed in Limassol on June 1, 1191. He was looking for his sister and his future wife, Berengaria. Their ship had been separated from the fleet in a storm.

Richard's army landed when Isaac Comnenus refused to return the hostages, which included Richard's sister, his bride, and some shipwrecked soldiers. Richard forced Isaac to flee from Limassol. Isaac eventually gave up, handing control of the island to the King of England. Richard married Berengaria in Limassol on May 12, 1192. She was crowned Queen of England there. The Crusader fleet then continued to St. Jean d'Acre on June 5 of the same year.

Richard the Lionheart's army continued to occupy Cyprus and collected taxes. He then sold the island to the Knights Templar. Soon after, a French army led by the House of Lusignan took control of the island. They established the Kingdom of Cyprus in 1192. They made Latin the official language, later changing it to French. Much later, Greek was recognized as a second official language.

In 1196, new church areas (dioceses) for the Latin Church were set up on the island. The Greek Orthodox Cypriot Church faced some religious difficulties from the Latin Catholics. Maronites, a Christian group, also settled in Cyprus during the Crusades and still have some villages in the North today.

Kingdom of Cyprus: French Rule

Amalric I of Cyprus (Aimery de Lusignan) received the title of king from Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor. A small number of Roman Catholic people lived on the island, mostly in coastal cities like Famagusta and the capital, Nicosia. These Roman Catholics held most of the power. Meanwhile, the Greek people lived mostly in the countryside. This was similar to how things were in the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The independent Eastern Orthodox Church of Cyprus, which had its own archbishop and was not controlled by any patriarch, was allowed to stay on the island. However, the Latin Church became more important and owned more property.

After Amalric of Lusignan died, the Kingdom of Cyprus was often ruled by young boys who became king. The Ibelin family, who had been powerful in Jerusalem, acted as regents (people who rule for a young king) during these early years. In 1229, one of the Ibelin regents was forced out by Frederick II, the Holy Roman Emperor. This brought a conflict between two groups, the Guelphs and Ghibellines, to the island.

Frederick's supporters were defeated in Cyprus by 1233. His descendants continued to rule as kings of Jerusalem until 1268. Then, Hugh III of Cyprus (died 1284) from the Lusignan family claimed the title and the territory of Acre for himself. This united the two kingdoms. The land in Palestine was finally lost in 1291, but the kings of Cyprus still claimed the title of King of Jerusalem.

Like Jerusalem, Cyprus had a "Haute Cour" (High Court). However, it was less powerful than the one in Jerusalem. Cyprus was richer and had more feudal lords than Jerusalem. This meant the king had more personal wealth and could sometimes ignore the High Court. The most important noble family was the Ibelin family.

However, the king often had problems with Italian merchants. This was because Cyprus became a major center for European trade with Africa and Asia after the city of Acre fell in 1291.

In the 14th century, the kingdom became more and more controlled by Genoese merchants. Cyprus then supported the Avignon Papacy during the Western Schism (a split in the Catholic Church). They hoped the French would help them get rid of the Italians.

The Mameluks then made the kingdom a state that had to pay tribute in 1426. The remaining kings slowly lost almost all their independence. This continued until 1489, when the last Queen, Catherine Cornaro, was forced to sell the island to Venice. The Ottomans started raiding Cyprus right after this. They finally captured it in 1571.

This historical period is the setting for Shakespeare's play Othello. The main character, Othello, is the commander of the Venetian army defending Cyprus against the Ottomans. {{wide image|Nicosia Venetian walls the Venetians ruled Cyprus from 1489 to 1571.JPG|600px|The Venetian walls of Nicosia, built to protect the city. The Venetians ruled Cyprus from 1489 to 1571.]]

Ottoman Cyprus: A New Era

Cyprus in 1571

In 1571, Cyprus became an Eyalet, which is a province, of the Ottoman Empire. It remained under Ottoman rule until 1878. The Ottoman Turks invaded Cyprus with a large fleet of ships and many soldiers. This was part of the Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573), also known as the War of Cyprus. After the conquest, Turks and Cypriots lived together on the island.

At that time, Cyprus was rich in salt, sugar, cotton, and grains. It was also an important place for trade between Syria and Venice. Because of this, Cyprus was a main trading center in the eastern Mediterranean for Venice.

Even after the Venetians lost control, they continued to trade with Cyprus. Merchants who had been imprisoned during the war were released, and their goods and ships were returned. Trade continued and was only stopped during wars. Venetian consuls were also present in Cyprus to help with trade and protect traders. The government of Cyprus even borrowed money from Venetian merchants in the early 16th century. Trade continued until the end of Ottoman rule.

Religion and Culture Under Ottoman Rule

The Ottoman Empire was mostly Muslim. So, when they conquered Cyprus, there was a mix of cultures and religions. As Cyprus became part of the Ottoman Empire, more Muslims came to the island. They mixed with the Orthodox Christian Greek population.

To keep peace, the Millet System was introduced in Cyprus. This system allowed religious authorities to govern their own religious groups. The Ottoman Empire also tried to spread Muslim culture in Cyprus. This especially affected women, as Islam encouraged them to cover their heads, and most women at the time followed this custom.

Changes in Cyprus's Administration

From 1670 onwards, the Ottomans changed how they governed Cyprus many times. It went from being a sanjak (a sub-province) to a personal property of the Grand vizier, then to an eyalet (a larger province), and back again.

| From | To | Type of Administration |

|---|---|---|

| 1670 | 1703 | A small province of the Archipelago Eyalet |

| 1730 | 1745 | A personal property of the Grand Vizier |

| 1745 | 1748 | A larger province (eyalet) |

| 1748 | 1784 | A personal property of the Grand Vizier |

| 1784 | ... | A small province of the Archipelago Eyalet |

Cyprus in 1878: End of Ottoman Rule

During the Russo-Turkish War, Cyprus prepared for an invasion. This war caused financial problems for the island for many years. Russia had spread ideas in the Mediterranean, encouraging Orthodox Greek Christians to fight against the Ottoman Empire. Cyprus tried to stay neutral, supporting the Ottomans with grain but also trying not to upset Russia.

The Russo-Turkish War ended Ottoman control of Cyprus in 1878. Cyprus then came under the control of the British Empire. This was agreed upon in the Cyprus Convention between the United Kingdom and the Ottoman Empire. However, the Ottoman Empire still officially owned the island until Great Britain took full control in 1914. This happened after Britain declared war on the Ottomans during World War I. After World War I, under the Lausanne Treaty, Turkey gave up all its claims to Cyprus.

Under British rule, people on the island gained more freedom of speech. This allowed Greek Cypriots to further develop their ideas of enosis (unification with Greece).

Modern Cyprus: Independence and Division

In 1878, the United Kingdom took over the government of Cyprus as a protectorate from the Ottoman Empire. In 1914, at the start of World War I, the Ottomans declared war on Britain. This led to Britain officially taking over Cyprus.

The people of Cyprus welcomed the British in 1878. They saw it as the end of long Turkish rule. They also hoped it would be a step towards Cyprus returning to Greece, similar to what happened with the Ionian Islands. In the 1920s, Greek Cypriot leaders decided to change their approach to enosis (union with Greece). Instead of demanding only union, they decided to try and gain some civil liberties for the Cypriot people first. The Political Organization of Cyprus was formed in 1921 for this purpose, but it was later dissolved.

Greek Cypriot representatives repeatedly asked England to unite Cyprus with Greece, but their requests were denied. Greek Cypriots also joined in Greece's national struggles, like the Balkan wars. This showed their belief in a shared history and future with Greece. Greek Cypriot volunteers also fought in World War I, hoping for a "Cypriot share" after the victory. However, at the Paris conference after World War I, Cyprus was not given to Greece.

After the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), Turkey gave up all its rights over Cyprus. This brought new hope that Cyprus would return to Greece. However, in 1925, England did not give Cyprus to Greece. Instead, they made it a Crown Colony, meaning it was directly ruled by the British Crown. British officials made it clear that unification was not going to happen, which disappointed Greek Cypriots.

The National Organization of Cyprus (EOK), founded in 1930 by church leaders, also pushed for enosis. They rejected the idea of autonomy (self-rule) proposed by the British. In 1931, the even more strict National Radical Union of the Center (ΕRΕΚ) was founded. The repeated rejections of Greek Cypriot hopes, along with other political events, led to a big uprising in October 1931, known as the October riots. Cyprus then entered a period of strict rule called Palmerokratia, named after Governor Richmond Palmer. This lasted until the start of World War II.

In January 1950, the Orthodox Church of Cyprus organized a referendum (a public vote) about Enosis. Greek Cypriots, who made up about 80% of the population, voted strongly in favor of joining Greece. However, the international community did not support their request.

Between 1955 and 1959, Greek Cypriots formed the EOKA organization, led by George Grivas. They began a fight for liberation, aiming for enosis. However, the EOKA campaign did not result in union with Greece. Instead, it led to an independent country, the Republic of Cyprus, in 1960.

The 1960 constitution created a power-sharing government. It included special rules for the Turkish Cypriots minority. For example, the vice-president of Cyprus and at least 30% of members of parliament had to be Turkish Cypriots. Archbishop Makarios III became the President, and Dr. Fazıl Küçük became vice president. The constitution also created separate local governments in large towns for Greek and Turkish Cypriots.

Internal conflicts turned into armed fighting between the two communities on the island. This led the United Nations to send peacekeeping forces in 1964. These forces are still there today. In 1974, Greek nationalists carried out a military coup with support from the military government in Greece. Turkey then invaded the northern part of the island. Turkish forces remained after a cease-fire, which led to the division of the island. The violence, the coup, and the invasion caused hundreds of thousands of Cypriots to become displaced from their homes.

The de facto (in reality, but not officially recognized) state of Northern Cyprus was declared in 1975. It was first called the Turkish Federated State of Cyprus. The name was changed to its current form, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, on November 15, 1983. Only Turkey recognizes Northern Cyprus. The international community considers it part of the Republic of Cyprus.

In 2002, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan started new talks to unite the island. In 2004, after long discussions, a plan for unification was created. This plan was supported by the United Nations, the European Union, and the United States. However, nationalists on both sides campaigned against the plan. As a result, Turkish Cypriots accepted the plan, but Greek Cypriots rejected it by a large majority.

After Cyprus joined the European Union in 2004, it adopted the euro as its currency on January 1, 2008. It replaced the Cypriot pound. Northern Cyprus continued to use the Turkish lira.

The political scene in Cyprus is mainly shaped by the communist AKEL, the liberal conservative Democratic Rally, the centrist Democratic Party, and the social-democratic EDEK.

In 2008, Dimitris Christofias became the country's first Communist head of state. He did not run for re-election in 2013 due to his involvement in the 2012–13 Cypriot financial crisis. In the 2013 Presidential election, Democratic Rally candidate Nicos Anastasiades won. He was sworn in on February 28, 2013. Anastasiades was re-elected in the 2018 presidential election. On February 28, 2023, Nikos Christodoulides became the eighth president of the Republic of Cyprus after winning the 2023 presidential election.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Chipre para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Chipre para niños

- Kingdom of Cyprus

- Timeline of Cypriot history

General: