History of Haiti facts for kids

The recorded history of Haiti began on December 5, 1492. This was when the European explorer Christopher Columbus landed on a large island in the Caribbean Sea. This island was home to the Taíno and Arawak people. They called their island Ayiti, Bohio, and Kiskeya. Columbus quickly claimed the island for the Spanish Empire and named it La Isla Española, which later became Hispaniola.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Early History of Hispaniola

Before the Spanish arrived, different groups of Arawak people moved north from South America and settled the Caribbean islands. Around the year 600 AD, the Taíno people, who were part of the Arawak culture, arrived on the island. They organized themselves into cacicazgos, which were like small kingdoms, each led by a cacique or chief.

Spanish Rule (1492–1625)

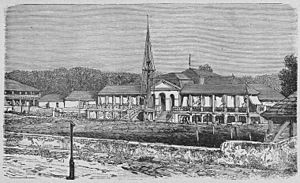

Christopher Columbus built a settlement called La Navidad in December 1492. It was near where the city of Cap-Haïtien is today. He used wood from his wrecked ship, the Santa María, to build it. When he came back in 1493, the settlement was destroyed, and all 39 settlers were gone. Columbus then moved east and started a new settlement called La Isabela in what is now the Dominican Republic. The main city of the Spanish colony later moved to Santo Domingo in 1496.

After the Europeans arrived, the native Taíno population on Hispaniola suffered greatly. Many died, mainly because they had no protection against European diseases. Their population dropped by as much as 95% in just 100 years. Many people believe this was a terrible event, like a genocide.

A small number of Taíno people managed to survive by creating new villages. Spain's interest in Hispaniola lessened in the 1520s. This was because they found more valuable gold and silver in Mexico and South America. So, the Spanish population on Hispaniola grew very slowly.

Spanish settlements in the western part of the island faced attacks from French pirates and English ships. In 1605, Spain was angry that its settlements on the northern and western coasts were trading illegally with the Dutch and English. These countries were enemies of Spain in Europe. So, Spain decided to force the people living there to move closer to Santo Domingo. This action, called the Devastaciones de Osorio, was very bad for the colonists. More than half of them died from hunger or sickness. Many slaves also escaped. Five of the thirteen settlements on the island were destroyed, including La Yaguana and Bayaja in what is now Haiti.

This Spanish action backfired. English, Dutch, and French pirates were now free to set up bases on the abandoned northern and western coasts. There were many wild cattle there for them to use. In 1697, after many years of fighting, Spain gave the western part of the island to the French. The French named their new colony Saint-Domingue.

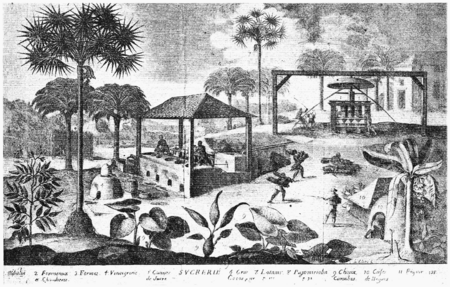

French Saint-Domingue (1625–1789)

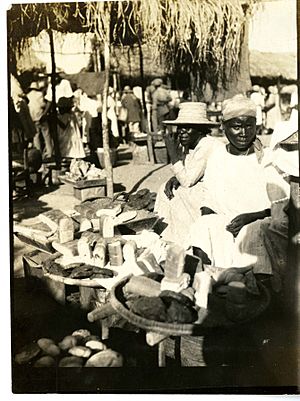

Saint-Domingue became a very rich colony for France. Its economy relied on growing sugar, which needed a lot of workers. So, many African slaves were brought to the island. Meanwhile, the Spanish part of the island became poorer.

The Pearl of the Antilles (1711–1789)

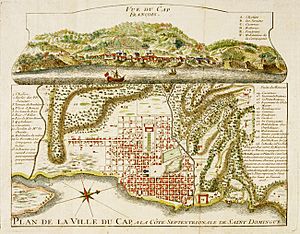

In 1711, the city of Cap-Français was officially started by Louis XIV. It became the new capital of the colony. Later, in 1749, Port-au-Prince was founded on the west coast. It became the capital in 1770, but a big earthquake and tsunami that year destroyed the city.

Before the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), Saint-Domingue's economy grew slowly. Sugar and coffee became important crops to export. After the war, the colony grew very quickly. By 1767, it was exporting huge amounts of sugar, indigo, and cotton. Saint-Domingue became known as the "Pearl of the Antilles". It was the richest colony in the 18th-century French empire. By the 1780s, this one colony produced about 40% of all the sugar and 60% of all the coffee used in Europe.

In the late 1780s, Saint-Domingue was responsible for a third of all the slave trade across the Atlantic Ocean. About 790,000 African slaves were brought to these plantations. Between 1764 and 1771, about 10,000 to 15,000 slaves were brought in each year. By 1787, more than 40,000 slaves arrived annually. However, because of the harsh conditions, the slave population could not grow on its own. So, by 1789, there were 500,000 slaves, ruled by only 32,000 white people. Most slaves were born in Africa.

African culture stayed strong among the slaves. This included the folk-religion of Vodou. It mixed Catholic traditions with beliefs from Africa. Slave traders brought people from many different tribes in Africa. Their languages were often very different.

To control slavery, Louis XIV created the Code Noir in 1685. This code gave some basic rights to slaves and duties to masters. Masters were supposed to feed, clothe, and care for their slaves. But the code also allowed harsh physical punishment. Masters often ignored the rules meant to protect slaves.

Thousands of slaves gained freedom by running away from their masters. They formed communities called maroons and attacked isolated plantations. The most famous maroon leader was François Mackandal. He was a one-armed slave from Guinea who escaped in 1751. He was a Vodou priest (Houngan) and united many maroon groups. For six years, he led successful raids and avoided capture. He was said to have killed over 6,000 people. He preached that white civilization in Saint-Domingue would be destroyed. In 1758, after a failed plan to poison plantation owners' water, he was caught and executed in Cap-Français.

Saint-Domingue also had the largest and richest population of free people of color in the Caribbean. These were called the gens de couleur. In 1789, there were 25,000 mixed-race people in Saint-Domingue. Often, the first gens de couleur were children of French slave owners and African slave women. These children were free and could inherit property. This created a group of mixed-race people who owned property and sometimes had wealthy fathers. This group was in the middle, between African slaves and French colonists. Africans who gained their freedom also became part of the gens de couleur.

As the number of gens de couleur grew, French rulers made unfair laws. These laws stopped gens de couleur from having certain jobs, marrying white people, wearing European clothes, carrying weapons, or going to social events with white people. However, these rules did not stop them from buying land. Many became rich landowners and even slave owners themselves. By 1789, they owned one-third of the plantations and one-quarter of the slaves in Saint-Domingue. The rise of the gens de couleur as planters was helped by the growing importance of coffee. Coffee grew well on the hillside plots they often owned. Most gens de couleur lived in the southern part of the colony.

Haitian Revolution (1789–1804)

The French Revolution in 1789 greatly affected the colony. While French settlers argued about new laws, a civil war started in 1790. Free men of color demanded to be French citizens, based on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. In Paris, a group of wealthy mixed-race men, led by Julien Raimond and Vincent Ogé, asked white planters to support their rights. In March 1790, the French National Assembly gave full civil rights to the gens de couleur.

Ogé's Revolt (1789–1791)

Vincent Ogé went to Saint-Domingue to make sure this new law was put into practice. He arrived near Cap-Français in October 1790 and asked the governor to follow the law. When his requests were refused, he tried to start a revolt among the gens de couleur. Ogé and Jean-Baptiste Chavannes, a soldier from the American Revolution, tried to attack Cap-Français. But the mixed-race rebels refused to arm their slaves or challenge slavery itself. Their attack was defeated by white militias and black volunteers, including Henri Christophe. Ogé and Chavannes fled to the Spanish part of the island. They were captured, returned to the French, and executed in February 1791.

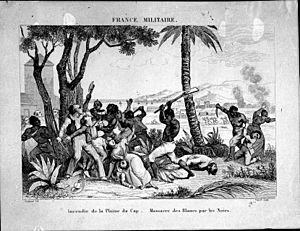

The Slave Uprising (1791–1793)

A Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman (Alligator Woods) on August 14, 1791, is often seen as the start of the Haitian Revolution. A Vodou priest named Dutty Boukman led the ceremony. After this, slaves in the northern part of the colony started a revolt. Even though Boukman was caught and executed, the rebellion quickly spread. In September, about thirteen thousand slaves and rebels in the south, led by Romaine-la-Prophétesse, freed slaves, took supplies, and burned plantations. They eventually took over the two main cities in the area, Léogâne and Jacmel.

In 1792, Léger-Félicité Sonthonax and two other French officials were sent to the colony. Sonthonax wanted to keep French control, make the colony stable, and ensure equal rights for free people of color. In March 1792, a group of whites and conservative free blacks, along with forces led by Edmond de Saint-Léger, stopped Romaine-la-Prophétesse's revolt.

Toussaint Louverture Rises (1793–1802)

On August 29, 1793, Sonthonax took a big step: he declared slaves in the northern province free. By October, this freedom was extended across the whole colony. The French National Convention, the first elected assembly of the French First Republic, officially abolished slavery in France and all its colonies on February 4, 1794.

However, the slaves did not immediately join Sonthonax. Planters who opposed the revolution continued to fight him, with support from the British. Many free men of color also joined them because they were against ending slavery. It was only when news of France's decision to end slavery reached the colony that Toussaint Louverture and his trained former slave soldiers joined the French side in May 1794.

When France declared war on Spain in January 1793, Spain sent its forces from Santo Domingo to fight alongside the slaves. By the end of 1793, Spain controlled most of the north. In 1795, Spain gave Santo Domingo to France, and Spanish attacks on Saint-Domingue stopped.

In the south, the British lost many battles to the mixed-race General André Rigaud. In 1798, after losing land and thousands of men to yellow fever, the British had to leave.

Meanwhile, Rigaud had started a mixed-race group in the south that wanted to be separate. With the British gone, Toussaint attacked Rigaud's strongholds in 1799. Toussaint's forces defeated Rigaud's in 1800.

By 1801, Toussaint controlled all of Hispaniola. He had conquered French Santo Domingo and ended slavery there. However, he did not declare full independence for the country. He believed the French would not bring back slavery.

Napoleon's Defeat (1802–1804)

Toussaint became so independent that in 1802, Napoleon sent a huge invasion force. It was led by his brother-in-law, Charles Leclerc. Leclerc's goal was to increase French control. For a while, Leclerc was successful. He also brought the eastern part of Hispaniola under direct French control. With a large army of 40,000 European soldiers, and help from white colonists and mixed-race forces, the French won some battles.

Two of Toussaint's main leaders, Dessalines and Henri Christophe, saw their situation was difficult. They talked with the French and agreed to switch sides. Leclerc then invited Toussaint to discuss a peace agreement. This was a trick. Toussaint was captured and sent to France. He died in prison in April 1803.

On May 20, 1802, Napoleon signed a law to keep slavery in colonies where it still existed. A secret copy of this law was sent to Leclerc. He was allowed to bring back slavery in Saint-Domingue when the time was right. At the same time, other orders took away the new civil rights of the gens de couleur. None of these orders were made public in Saint-Domingue. But by mid-summer, news reached the colony that the French planned to bring back slavery.

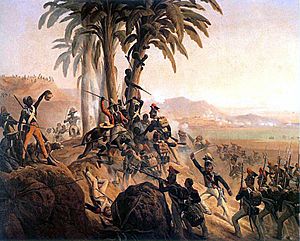

The betrayal of Toussaint and the news from Martinique made leaders like Dessalines, Christophe, and Alexandre Pétion turn against Leclerc again. They believed the same fate awaited Saint-Domingue. The war became a very bloody fight. The rainy season brought yellow fever and malaria, which killed many French soldiers. By November, when Leclerc died of yellow fever, 24,000 French soldiers were dead.

Leclerc was replaced by Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, Vicomte de Rochambeau. Rochambeau wrote to Napoleon that to take back Saint-Domingue, France must "declare the negroes slaves, and destroy at least 30,000 negroes and negresses." Rochambeau's brutal actions helped unite black and mixed-race soldiers against the French.

As the war turned in favor of the former slaves, Napoleon gave up his plans for a French empire in the New World. In 1803, war started again between France and Britain. The British navy controlled the seas, so Rochambeau did not get enough supplies or soldiers. To focus on the war in Europe, Napoleon sold France's North American lands to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase. The Haitian army, now led by Dessalines, defeated Rochambeau and the French army at the Battle of Vertières on November 18, 1803.

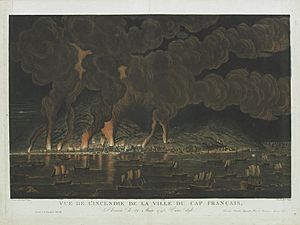

On January 1, 1804, Dessalines declared independence. He renamed the new nation Haiti, using the native Taíno name meaning "Land of Mountains." Most of the remaining French colonists fled. Unlike Toussaint, Dessalines was very harsh towards the white French. In a final act of revenge, the remaining French were killed by Haitian soldiers. About 2,000 Frenchmen were killed in Cap-Français, 900 in Port-au-Prince, and 400 in Jérémie.

One group that was spared were some Poles who had joined the French army. Many Polish soldiers refused to fight against the Haitian forces. They felt a connection to the Haitians because they were also fighting for their own freedom back home in Poland. As a result, many Polish soldiers admired their enemy and decided to join the Haitian slaves. They helped in the revolution. For their loyalty, some Poles became Haitian citizens after Haiti gained independence. Many settled there and never returned to Poland. Today, descendants of these Poles still live in Haiti.

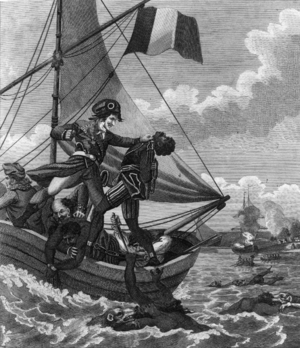

After Haiti became independent, the new nation faced economic struggles. European countries and the United States refused to recognize Haiti as an independent nation. In 1825, the French returned with a fleet of fourteen warships. They demanded a payment of 150 million francs in exchange for recognizing Haiti. Haitian President Jean-Pierre Boyer was forced to agree. To pay this debt, the Haitian government had to take out many high-interest loans from foreign lenders. The debt to France was not fully paid until 1947.

Early Years of Independence (1804–1843)

Haiti Becomes a Black Republic (1804)

Haiti is the world's oldest black republic and one of the oldest republics in the Western Hemisphere. Haiti helped many other Latin American countries gain independence. For example, it helped Simón Bolívar and he promised to free slaves after winning independence from Spain. However, Haiti was not allowed to join the first meeting of independent nations in Panama in 1826. The United States did not recognize Haiti's independence until 1862. This was because Southern slave states in the US feared it would encourage slave revolts.

When General Dessalines took power, he approved the Constitution of 1804. This constitution brought important social freedoms:

- It allowed freedom of religion. (Under Toussaint, Catholicism had been the official religion).

- All citizens of Haiti, no matter their skin color, were to be called "Black." This was an effort to get rid of the old racial system.

- White men were not allowed to own property in Haiti.

- If the French tried to bring back slavery, the constitution said: "At the first shot of the warning gun, the towns shall be destroyed and the nation will rise in arms."

First Haitian Empire (1804–1806)

On September 22, 1804, Dessalines declared himself Emperor Jacques I. But two of his own advisors, Henri Christophe and Alexandre Pétion, helped plan his assassination. He was attacked and killed on October 17, 1806, north of Port-au-Prince.

The country Dessalines created was different from what most Haitians, especially the farmers, wanted. Both the leaders and the people agreed that Haiti should be free and democratic. But they had different ideas about what freedom meant. The leaders wanted a strong economy and military to stay independent from other countries. They believed this would ensure freedom.

However, the Haitian farmers saw freedom as being able to grow their own food on small plots of land. Because of the mountains, many slaves had been able to do this. But the leaders wanted a system of forced farm work to make the country rich. Also, while everyone wanted a black republic, there were disagreements about African culture. Many Haitians wanted to keep their African heritage. But the elites often tried to show that Haitians were sophisticated through literature. Some said African "barbarism" should be removed, while still keeping African roots.

The government was mostly run by the military. This made it hard for ordinary Haitians to take part in government. The state also failed to provide good education, which was badly needed by former slaves who had been denied schooling. This meant they could not participate effectively. Because of these different ideas about freedom, the elites created a state that mostly benefited themselves, not the general population.

Struggle for Unity (1806–1820)

After Dessalines' death, the two main plotters divided the country. Christophe created an authoritarian state in the north, and Pétion, a mixed-race leader, started a republic in the south. Christophe tried to keep a strict system of labor, similar to the old plantations. He made every able man work on farms to produce goods for the country. This system, though harsh, made more money than the southern government.

Pétion, on the other hand, broke up the old plantations and gave small pieces of land to farmers. In Pétion's south, the mixed-race minority led the government. They feared losing public support, so they tried to ease tensions by giving out land. Because of its weak international position and farming policies, Pétion's government was often close to going broke. But for most of its time, it was one of Haiti's most liberal governments. In 1815, Pétion gave Simón Bolívar, a leader fighting for Venezuela's independence, a safe place to stay and provided him with soldiers and supplies.

In 1811, Henri Christophe declared himself King Henri I of the Kingdom of Haiti in the North. He built many impressive buildings and even created a noble class like European kings. But in 1820, weakened by illness and losing support, he died. Immediately after, Pétion's successor, Jean-Pierre Boyer, reunited Haiti using diplomacy. He ruled as president until he was overthrown in 1843.

Boyer Unites Hispaniola (1820–1843)

Almost two years after Boyer took control of western Haiti, Haiti invaded Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic). Boyer occupied the former Spanish colony in January 1822 without any fighting. This united the entire island under Haitian rule, something only Toussaint Louverture had done briefly in 1801. This occupation, however, made the Spanish white elite angry and caused many wealthy families to leave. The whole island stayed under Haitian rule until 1844. Then, a group called La Trinitaria led a revolt in the east, dividing the island into Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

From 1824 to 1826, Boyer encouraged the largest single migration of free black people from the United States to Haiti. More than 6,000 immigrants settled in different parts of the island. Today, some of their descendants live in places like Samaná in the Dominican Republic. The government wanted these immigrants to help build trade with the US and increase the number of skilled workers and farmers in Haiti.

To get diplomatic recognition from France, Boyer was forced to pay a huge amount of money for the French property lost during the revolution. To pay this, he had to take out loans from France, putting Haiti deep in debt. Boyer tried to force people to work on plantations using the Code Rural in 1826. But the farmers, many of whom were former revolutionary soldiers, did not want to return to forced labor. By 1840, Haiti had stopped exporting sugar entirely. However, Haiti continued to export coffee, which needed less work and grew almost wild.

The 1842 Cap-Haïtien earthquake destroyed the city of Cap-Haïtien and the Sans-Souci Palace. It killed 10,000 people. This was the third major earthquake to hit western Hispaniola.

Political Struggles (1843–1915)

In 1843, a revolt led by Charles Rivière-Hérard overthrew Boyer. A short period of parliamentary rule followed. But revolts soon broke out, and the country fell into chaos. There were many short-term presidents until March 1847. Then, General Faustin Soulouque, a former slave who fought in the 1791 rebellion, became president. During this time, Haiti fought unsuccessfully against the Dominican Republic.

In 1849, President Faustin Soulouque declared himself Emperor Faustin I. His strong rule united Haiti for a while. But it ended suddenly in 1859 when General Fabre Geffrard removed him from power.

Geffrard's military government ruled until 1867. He encouraged national peace. In 1860, he made an agreement with the Vatican. This brought official Roman Catholic schools back to Haiti. In 1867, there was an attempt to create a constitutional government. But presidents Sylvain Salnave and Nissage Saget were overthrown in 1869 and 1874. A better constitution was introduced under Michel Domingue in 1874. This led to a long period of peace and development for Haiti. The debt to France was finally paid in 1879. Domingue's government peacefully handed power to Lysius Salomon, one of Haiti's best leaders. Money reforms happened, and Haitian art and culture flourished.

The late 1800s also saw the growth of Haitian intellectual culture. Important history books were published. Haitian thinkers, like Louis-Joseph Janvier and Anténor Firmin, fought against racism that was common at the time.

The Constitution of 1867 brought peaceful changes in government. This greatly improved Haiti's economy and stability. The development of sugar and rum industries near Port-au-Prince made Haiti a model for economic growth in Latin America for a while.

This period of peace and wealth ended in 1911. A revolution broke out, and the country again fell into disorder and debt. From 1911 to 1915, there were six different presidents. Each one was either killed or forced to leave the country. The revolutionary armies were made up of cacos. These were peasant fighters from the northern mountains. They were hired by different political groups with promises of money and a chance to take goods after a successful revolution.

The United States was worried about the German community in Haiti. About 200 Germans lived there in 1910, but they had a lot of economic power. Germans controlled about 80% of Haiti's international trade. They also owned and ran utilities in Cap-Haïtien and Port-au-Prince.

The German community was more willing to become part of Haitian society than other white foreigners. Many married into important mixed-race families, getting around the law that stopped foreigners from owning land. They also lent money to different political groups during the many revolutions, often at high interest rates.

To limit German influence, the US State Department supported American investors in 1910–1911. This group, led by the National City Bank of New York, took control of Haiti's currency. They replaced the old National Bank of Haiti as the country's only commercial bank and keeper of the government's money.

In February 1915, Vilbrun Guillaume Sam became a dictator. But in July, facing a new revolt, he ordered the killing of 167 political prisoners. All of them were from important families. A mob in Port-au-Prince then killed him.

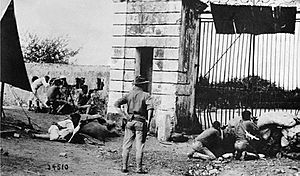

United States Occupation (1915–1934)

In 1915, the United States occupied Haiti. This happened because American banks, to whom Haiti owed a lot of money, complained to President Woodrow Wilson. The occupation lasted until 1934. Haitians did not like the US occupation because they felt they had lost their independence. There were revolts against the US forces. Despite this, some improvements were made.

Under the US Marines' supervision, the Haitian National Assembly elected Philippe Sudré Dartiguenave as president. He signed a treaty that made Haiti a US protectorate. American officials took control of Haiti's finances, customs, police, public works, and health services for ten years. The main tool of American power was the new Gendarmerie d'Haïti, led by American officers. In 1917, at the US's request, the National Assembly was closed. Officials were chosen to write a new constitution, mostly dictated by US officials. This new document removed the ban on foreigners owning land, which was a very important Haitian law. When the new National Assembly refused to pass this and wrote its own version, it was forced to close by the Gendarmerie commander, Smedley Butler. This constitution was approved by a public vote in 1919, but less than 5% of the people voted.

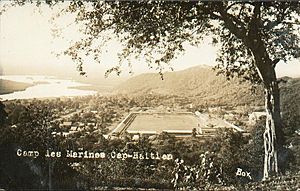

The Marines and Gendarmerie started a large road-building program. This was to help their military and open the country for US businesses. They didn't have enough money, so they brought back an old Haitian law. This law made peasants work on local roads instead of paying a road tax. This system, called the corvée, was like the unpaid labor peasants did for feudal lords in France. In 1915, Haiti had only 3 miles of roads usable by cars outside of towns. By 1918, over 470 miles of roads had been built or fixed using the corvée system. However, Haitians forced to work in these labor groups felt like it was a return to slavery.

In 1919, a new caco uprising began, led by Charlemagne Péralte. He promised to "drive the invaders into the sea and free Haiti." The Cacos attacked Port-au-Prince in October but were pushed back. Later, an American officer and two US Marines killed Péralte. The rebellion continued under Benoît Batraville, but his death in 1920 ended the fighting. During Senate hearings in 1921, it was reported that 2,250 Haitians were killed during the resistance. However, other reports suggested the number was higher.

In 1922, Louis Borno replaced Dartiguenave. He ruled without a legislature until 1930. That same year, General John H. Russell, Jr. was appointed High Commissioner. The Borno-Russel government improved the economy. They built over 1000 miles of roads, set up an automatic telephone system, modernized ports, and created a public health service. Sisal was brought to Haiti, and sugar and cotton became important exports. However, most Haitians still disliked the loss of their independence.

The Great Depression caused the prices of Haiti's exports to crash. In December 1929, Marines in Les Cayes killed ten Haitians during a protest. This led US President Herbert Hoover to send two commissions to Haiti. They criticized the fact that Haitians were not given important jobs in the government and police. In 1930, Sténio Vincent, who had long criticized the occupation, was elected president. The US began to withdraw its forces. The withdrawal was completed in 1934 under US President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Good Neighbor policy". The US kept control of Haiti's finances until 1947.

All three rulers during the occupation were from Haiti's mixed-race minority. At the same time, many in the growing black professional class started to focus on Haiti's African roots, rather than just its French culture.

The government left behind had better infrastructure, public health, education, and farming development. It also had a democratic system. Haiti had fully democratic elections in 1930, won by Sténio Vincent. The police force, now called the Garde, was new. It was mostly made up of black Haitians, with a US-trained black commander. Most of the Garde's officers were mixed-race. The Garde was a national organization. It was supposed to be non-political, maintaining order and supporting an elected government. At first, it did this.

Elections and Changes in Power (1934–1957)

Vincent's Presidency (1934–1941)

President Vincent used the country's stability, kept by a professional military, to gain total power. A public vote allowed him to take all power over economic matters from the legislature. But Vincent wanted even more power. In 1935, he forced a new constitution through the legislature, which was also approved by a public vote. This constitution praised Vincent and gave him huge powers. He could close the legislature, change the courts, appoint many senators, and rule by decree when the legislature was not meeting. Although Vincent improved some infrastructure and services, he harshly stopped his opponents, censored the press, and mostly ruled to benefit himself and a small group of corrupt officials.

Under the police commander Calixte, most police officers had followed the rule of not getting involved in politics. However, over time, Vincent and Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo tried to buy loyalty among the officers. Trujillo wanted to increase his power over all of Hispaniola. In October 1937, he ordered the killing of an estimated 14,000 to 40,000 Haitians on the Dominican side of the border. Some say Trujillo supported a failed attempt by young police officers to overthrow Vincent in December 1937. Vincent fired Calixte and sent him abroad. This attempt to overthrow the government led Vincent to remove any officers he suspected of disloyalty. This marked the end of the military being non-political.

Lescot's Presidency (1941–1946)

In 1941, Vincent wanted to be president for a third term. But after almost ten years, the United States said it would not support this. Vincent agreed and handed power to Élie Lescot.

Lescot was of mixed race and had held many government jobs. He was capable and strong, and many thought he would be a great president. However, like many Haitian presidents before him, he did not live up to his potential. His time in office was similar to Vincent's. Lescot declared himself commander-in-chief of the military. Power was held by a small group that ruled with the quiet support of the police. He stopped his opponents, censored the press, and forced the legislature to give him wide powers. He handled all money matters without the legislature's approval. Lescot often said that Haiti's declaration of war against the Axis powers in World War II justified his harsh actions. Haiti, however, did not play a big role in the war, except for supplying raw materials to the United States.

Besides his authoritarian ways, Lescot had another problem: his relationship with Rafael Trujillo. While serving as Haiti's ambassador to the Dominican Republic, Lescot came under Trujillo's influence and wealth. In fact, it was Trujillo's money that reportedly bought most of the votes that brought Lescot to power. Their secret connection lasted until 1943, when they separated for unknown reasons. Trujillo later made all his letters with Lescot public. This hurt Lescot's already weak public support.

In January 1946, things came to a head when Lescot jailed the Marxist editors of a journal called La Ruche (The Beehive). This caused student strikes and protests by government workers, teachers, and shopkeepers in the capital and other cities. Also, Lescot's rule, which was dominated by mixed-race people, had angered the mostly black police force. His position became impossible, and he resigned on January 11. Radio announcements said that the police had taken power. They would rule through a three-member group.

Revolution of 1946

The Revolution of 1946 was new for Haiti. The police force took power as a group, not just as a tool for one commander. The members of this group, called the Military Executive Committee, were police commander Colonel Franck Lavaud, Major Antoine Levelt, and Major Paul E. Magloire. They understood Haiti's traditional way of ruling, but they didn't fully understand what it would take to switch to an elected civilian government. When they took power, the group promised to hold free elections. Public demand, including demonstrations, eventually forced them to keep their promise.

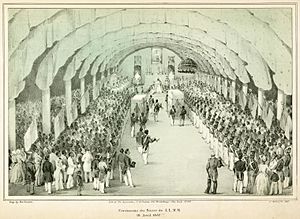

Haiti elected its National Assembly in May 1946. The Assembly set August 16, 1946, as the day it would choose a president. The main candidates were all black. They included Dumarsais Estimé, a former teacher and minister; Félix d'Orléans Juste Constant, leader of the Haitian Communist Party; and former police commander Démosthènes Pétrus Calixte. Estimé was the most moderate. He had support from black people in the north and the growing black middle class. The military leaders also saw Estimé as the safest choice. After two rounds of voting, Estimé became president.

Estimé's Presidency (1946–1950)

Estimé's election was a change in Haiti's politics. Although he was said to have military support, Estimé was a civilian. He came from humble beginnings and was strongly against the elite, especially the mixed-race elite. At first, he genuinely cared about the people's well-being. Under a new constitution from November 1946, Estimé tried to pass Haiti's first social security law, but it never passed. However, he did expand the school system, encourage rural cooperatives, raise civil servants' salaries, and increase the number of middle-class and lower-class black people in public jobs. He also tried to gain the favor of the military by promoting Lavaud to general and seeking US military help.

Estimé eventually fell victim to two common problems in Haitian rule: elite plotting and personal ambition. The elite had many complaints against Estimé. He had mostly kept them out of profitable government jobs. He also created the country's first income tax, supported labor unions, and suggested that Vodou be seen as equal to Catholicism. The Europeanized elite hated this idea. Since they had little direct power, the elite secretly lobbied military officers. Their efforts, along with worsening conditions in the country, led to a coup in May 1950.

Estimé had also caused his own downfall. His nationalization of the banana company reduced its income. He angered workers by making them invest part of their salaries in national defense bonds. The president sealed his fate by trying to change the constitution to stay in office longer. The army used this action and the public unrest it caused to force him to resign on May 10, 1950. The same military group that took power after Lescot's fall returned. Estimé was escorted from the National Palace and sent into exile in Jamaica. The events of May 1946 made a strong impression on François Duvalier, who was then the minister of labor. Duvalier learned that the military could not be trusted. He would act on this lesson when he gained power.

Magloire's Presidency (1950–1956)

The balance of power within the military group changed between 1946 and 1950. Lavaud was the most important member during the first coup, but Magloire, now a colonel, was in charge after Estimé was overthrown. When Haiti announced its first direct elections (all men 21 or older could vote) for October 8, 1950, Magloire resigned from the military group and announced he would run for president. Unlike the chaotic political situation of 1946, the 1950 campaign was understood to mean that only a strong candidate supported by both the army and the elite would be able to take power. Facing little opposition, Magloire won the election and took office on December 6.

Magloire brought the elite back into power. Businesses and the government benefited from good economic conditions until Hurricane Hazel hit the island in 1954. Haiti made some improvements to its infrastructure, but most of these were paid for by foreign loans. By Haitian standards, Magloire's rule was firm but not overly harsh. He jailed political opponents and closed their newspapers when protests grew too loud. But he allowed labor unions to exist, though they couldn't strike. However, Magloire went too far with corruption. The president controlled the sisal, cement, and soap businesses. He and other officials built huge mansions. International hurricane relief money, added to an already corrupt system, increased corruption to levels that upset all Haitians. To make things worse, Magloire tried to stay in office longer than his term allowed. Politicians, labor leaders, and their supporters protested in the streets in May 1956. Although Magloire declared martial law, a general strike shut down Port-au-Prince. Like many before him, Magloire fled to Jamaica, leaving the army to restore order.

The Rise of Duvalier (1956–1957)

The time between Magloire's fall and Duvalier's election in September 1957 was very chaotic, even for Haiti. Three temporary presidents held office during this time. One resigned, and the army removed the other two. Duvalier is said to have been very active behind the scenes, helping himself become the military's favored presidential candidate. The military then guided the campaign and elections to give Duvalier every possible advantage. Most people saw Duvalier, a doctor who had worked in rural health before joining the government, as an honest and modest leader without strong political ideas. When elections were finally held, this time with all men and women aged 21 or over allowed to vote, Duvalier presented himself as the rightful successor to Estimé. This helped him because his only real opponent, Louis Déjoie, was mixed-race and from a prominent family. Duvalier won the election by a large margin. His supporters won two-thirds of the lower house of the legislature and all the seats in the Senate.

The Duvalier Era (1957–1986)

'Papa Doc' (1957–1971)

François Duvalier, known as "Papa Doc", soon became a dictator. His government is seen as one of the most oppressive and corrupt in modern times. He used violence against political opponents and used Vodou to scare most people. Duvalier's special police, called the Tonton Macoutes, carried out political killings, beatings, and intimidation. An estimated 30,000 Haitians were killed by his government. He included many Vodou priests in the Macoutes. His public support of Vodou and his private practice of Vodou rituals, along with his rumored knowledge of magic, made him popular among common people and gave him a strange kind of power.

Duvalier's policies aimed to end the power of the mixed-race elite over the country's economy and politics. This led to many educated people leaving Haiti, making Haiti's economic and social problems worse. However, Duvalier appealed to the black middle class by building roads, providing running water, and modern sewage systems in their neighborhoods, which had not had these before. In 1964, Duvalier declared himself "President for Life."

The Kennedy government stopped aid in 1961. This was after claims that Duvalier had stolen aid money and planned to use a US Marine Corps mission to strengthen his police force. Duvalier also had conflicts with Dominican President Juan Bosch in 1963. Bosch had helped Haitian exiles who wanted to overthrow Duvalier. Duvalier ordered his Presidential Guard to take over the Dominican embassy in Pétion-Ville to catch an officer involved in a plot to kidnap his children. This led Bosch to publicly threaten to invade Haiti. However, the Dominican army did not support an invasion, and the dispute was settled by international groups.

'Baby Doc' (1971–1986)

When Duvalier died in April 1971, his 19-year-old son Jean-Claude Duvalier, known as "Baby Doc", took power. Under Jean-Claude Duvalier, Haiti's economy and political situation continued to get worse. However, some of the scarier parts of his father's rule were removed. Foreign officials and observers seemed more accepting of Baby Doc, especially regarding human rights. Foreign countries also gave him more economic help. The United States restarted its aid program in 1971. In 1974, Baby Doc took over the Freeport Tortuga project, which caused it to fail.

Jean-Claude was happy to let his mother, Simone Ovid Duvalier, handle government matters. He made himself rich through dishonest schemes. Much of the Duvaliers' wealth, hundreds of millions of dollars over the years, came from the Régie du Tabac (Tobacco Administration). This was a tobacco business started by Estimé, which grew to include money from all government businesses. It was used as a secret fund with no records. His marriage in 1980 to a beautiful mixed-race woman, Michèle Bennett, in a $3 million ceremony, caused widespread anger. It was seen as a betrayal of his father's dislike for the mixed-race elite. At Michèle's request, Papa Doc's widow Simone was forced to leave Haiti.

Baby Doc's corrupt rule made the government weak against unexpected problems. These were made worse by widespread poverty. One major problem was the epidemic of African swine fever virus. At the request of US officials, this led to the killing of the creole pigs, which were the main source of income for most Haitians. Another problem was the widely reported outbreak of AIDS in the early 1980s. Widespread unhappiness in Haiti began in 1983 when Pope John Paul II criticized the government during a visit. This finally led to a rebellion. In February 1986, after months of disorder, the army forced Duvalier to resign and go into exile.

Struggle for Democracy (1986–Present)

Transitional Government (1986–1990)

From 1986 to early 1988, Haiti was ruled by a temporary military government under General Namphy. In 1987, a new constitution was approved. It created an elected parliament with two houses, an elected president, and a prime minister and cabinet chosen by the president with parliament's approval. The constitution also allowed for local governments with elected mayors. The November 1987 elections were canceled after soldiers killed many voters on election day. Jimmy Carter later wrote that "Citizens who lined up to vote were mowed down by fusillades of terrorists' bullets." The election was followed by another one in 1988, which most candidates boycotted. Only 4% of people voted.

The 1988 elections led to Leslie Manigat becoming president. But three months later, the military removed him too. More instability followed, with several massacres. During this time, the Haitian National Intelligence Service (SIN) was set up and funded by the US.

The Rise of Aristide (1990–1991)

In December 1990, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a Roman Catholic priest, won 67% of the vote in elections. International observers said these elections were mostly fair. Aristide's popular policies and the violence of his supporters worried many of the country's elite. In September 1991, he was overthrown in a coup. General Raoul Cédras took power. Hundreds of people were killed, and Aristide was forced into exile. His life was saved by international diplomatic help.

Military Rule (1991–1994)

An estimated 3,000–5,000 Haitians were killed during the military rule. The coup caused many refugees to flee to the United States. The United States Coast Guard stopped 41,342 Haitians in 1991 and 1992. Most were not allowed into the US and were sent back to Haiti. Aristide has accused the United States of supporting the 1991 coup. In response to the coup, the United Nations Security Council imposed international penalties and an arms ban on Haiti.

On February 16, 1993, the ferry Neptune sank, and about 700 passengers drowned. This was the worst ferry disaster in Haitian history.

The military government ruled Haiti until 1994. Many attempts to end the crisis and bring back the elected government failed. In July 1994, as the repression in Haiti grew, the United Nations Security Council allowed member states to use all necessary means to remove Haiti's military leaders and restore the elected government.

Aristide Returns (1994–1996)

In mid-September 1994, with US troops ready to enter Haiti by force, President Bill Clinton sent a team led by former president Jimmy Carter. Their goal was to convince the authorities to step down and allow the elected government to return. With troops already in the air, Cédras and other top leaders agreed to leave. In October, Aristide was able to return. The elections in June 1995 saw Aristide's group win a big victory. René Préval, a close ally of Aristide, was elected president with 88% of the vote. When Aristide's term ended in February 1996, this was Haiti's first time having two democratically elected presidents transition power peacefully.

Préval's First Presidency (1996–2001)

In late 1996, Aristide broke with Préval and formed a new political party. This party won elections in April 1997 for some Senate and local assembly seats. However, the government did not accept these results. The split between Aristide and Préval caused a dangerous political standstill. The government could not organize local and parliamentary elections due in late 1998. In January 1999, Préval dismissed lawmakers whose terms had ended. He then ruled by decree.

Aristide's Second Presidency (2001–2004)

In May 2000, elections for the Chamber of Deputies and two-thirds of the Senate took place. Over 60% of voters participated, and Aristide's party won almost all seats. However, the elections were controversial. There were disputes over how votes were counted in the Senate race. The Organization of American States complained and refused to observe the next round of elections. Opposition parties demanded that the elections be canceled. They wanted Préval to step down and be replaced by a temporary government. The opposition announced it would boycott the November presidential and senatorial elections. Haiti's main aid donors threatened to cut off aid. In the November 2000 elections, which the opposition boycotted, Aristide was again elected president with over 90% of the vote. The opposition refused to accept the result or recognize Aristide as president. Because of these events, the European Union and the United States stopped giving aid to Haiti.

Aristide spent years trying to negotiate with the opposition for new elections. But the opposition did not have enough support to win elections, so they rejected every deal. They preferred to call for a US invasion to remove Aristide.

The 2004 Coup d'état

Anti-Aristide protests in January 2004 led to violent clashes in Port-au-Prince, causing several deaths. In February, a revolt started in the city of Gonaïves, which rebels soon controlled. The rebellion spread, and Cap-Haïtien, Haiti's second-largest city, was captured. A group of diplomats offered a plan to reduce Aristide's power while letting him stay in office until his term ended. Although Aristide accepted the plan, the opposition rejected it.

On February 29, 2004, with rebel groups marching towards Port-au-Prince, Aristide left Haiti. Aristide says he was kidnapped by the US. The US State Department says he resigned. Aristide and his wife left Haiti on an American plane, escorted by American diplomats and military. They were flown to Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic.

Many observers believe the US has not given clear answers about the coup. For example, how did the US get Aristide's supposed letter of "resignation"? The letter, translated from Haitian Creole, may not have actually been a resignation.

Aristide has accused the US of removing him from power with the help of the Haitian opposition. He said in a 2006 interview that the US broke promises about privatizing businesses. He claimed they then used a "disinformation campaign" to discredit him.

Political groups and writers, as well as Aristide himself, have suggested that the rebellion was actually a foreign-controlled coup. Caricom, which supported the peace deal, accused the United States, France, and the international community of failing Haiti. They said these countries allowed a controversially elected leader to be violently forced out of office. The international community said the crisis was Aristide's fault and that he was not acting in Haiti's best interest. They argued that his removal was needed for future stability.

Investigators claimed to have found widespread corruption by Aristide. It was said Aristide had stolen millions of dollars from the country. However, none of the claims about Aristide's involvement in corruption could be proven. The criminal case against Aristide was quietly put aside.

The government was taken over by Supreme Court Chief Justice Boniface Alexandre. Alexandre asked the United Nations Security Council for an international peacekeeping force. The Security Council approved the mission the same day. A group of about 1,000 US Marines arrived in Haiti within the day. Canadian and French troops arrived the next morning. On June 1, 2004, the peacekeeping mission was taken over by MINUSTAH. It had 7,000 soldiers led by Brazil and supported by other countries.

In November 2004, the University of Miami School of Law investigated human rights in Haiti. They found serious abuses and stated that "summary executions are a police tactic."

In March 2004, the Haiti Commission of Inquiry said that 200 US special forces had traveled to the Dominican Republic for "military exercises" in February 2003. The commission accused the US of arming and training Haitian rebels there.

On October 15, 2005, Brazil asked for more troops to be sent because the situation in Haiti was getting worse. After Aristide was overthrown, violence continued in Haiti, even with peacekeepers present. Clashes between police and Aristide's supporters were common. Peacekeeping forces were accused of a massacre in Cité Soleil in July 2005. Several protests led to violence and deaths.

Préval's Second Presidency (2006–2011)

Despite the ongoing violence, the temporary government planned elections. After being delayed several times, they were held in February 2006. The elections were won by René Préval, who was popular among the poor, with 51% of the votes. Préval took office in May 2006.

In the spring of 2008, Haitians protested against rising food prices. In some cases, main roads were blocked, and the airport in Port-au-Prince was closed. Protests by Aristide's supporters continued in 2009.

Earthquake of 2010

On January 12, 2010, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, was hit by a terrible earthquake. It had a magnitude of 7.0. The Haitian government estimated the death toll at over 300,000. Other sources estimated it between 50,000 and 220,000. Aftershocks followed, including one of magnitude 5.9. The capital city, Port-au-Prince, was almost completely destroyed. A million Haitians lost their homes, and hundreds of thousands went hungry. The earthquake caused massive damage, with most buildings crumbling, including Haiti's presidential palace. The huge number of deaths made it necessary to bury the dead in mass graves. Most bodies were not identified, making it impossible for families to find their loved ones. The spread of disease was a major problem after the earthquake. Many survivors were treated for injuries in emergency hospitals, but many more died from infections and lack of food.

The Martelly Presidency (2011–2016)

On April 4, 2011, a Haitian official announced that Michel Martelly had won the second round of the election against Mirlande Manigat. The election involved voter suppression and other ways of rigging. Michel Martelly, also known as "Sweet Micky," is a former musician and businessman. Martelly's government faced both anger and praise. He and his associates were accused of money laundering and other crimes, leading to many protests. Many criticized him for the slow progress of rebuilding after the earthquake. Others believed he was the most productive Haitian president since the Duvalier era.

Under his government, most of those left homeless after the earthquake were given new housing. He offered free education programs to many Haitian young people. He also created an income program for Haitian mothers and students. His government started a huge rebuilding program in the main government district, Champs-de-Mars. This program modernized and repaired various government buildings, public places, and parks. Michel Martelly focused on foreign investment and business with his slogan "Haiti is Open for Business." One of the biggest contributions to Haiti's economy was his push for tourism. Tourism increased significantly between 2012 and 2016. On February 8, 2016, Michel Martelly stepped down at the end of his term without a successor.

The Moïse Presidency (2017–2021)

After Hurricane Mathew, Jovenel Moïse was chosen to be president in an election that activists called an "electoral coup d'etat." The election was overseen by the United States, which has a history of interfering with democratic processes in Latin America, including Haiti. He was sworn in on February 7, 2017. He started the "Caravan de Changement" project. This project aimed to improve industries and infrastructure in less popular areas of Haiti. However, the real impact of these efforts is debated. In recent months, Moïse has been accused of stealing money from the PetroCaribe program, as has his predecessor, Martelly.

On July 7, 2018, protests led by opposition politician Jean-Charles Moïse began. They demanded that Jovenel Moïse resign. A Senate investigation from November 2017 looked into the period from 2008-2016. It found that a lot of corruption had been funded with loans from Venezuela through the Petrocaribe program. Big protests broke out in February 2019 after a report from the court investigating the Petrocaribe probe.

New protests started in February 2021 over a disagreement about Moïse's presidential term. Protesters claimed that Moïse's term officially ended on February 7, 2021, and demanded he step down. Moïse, however, claimed he had one more year to serve because of delays in starting his term. Protesters also worried about a public vote proposed by Moïse. This vote would reportedly remove the ban on presidents serving consecutive terms, allowing Moïse to run again.

On July 7, 2021, President Moïse was assassinated. Prime Minister Claude Joseph declared himself interim president.

The Henry Presidency (2021-Present)

Ariel Henry has been the acting prime minister and acting president since July 20, 2021.

2021 Earthquake

On August 14, 2021, a strong 7.2 earthquake hit Haiti. It caused tsunami warnings on the Haitian Coast, but these were later canceled. The earthquake killed 1,419 people by August 15, 2021.

Gang Violence

On July 7, 2022, major clashes between two rival gangs began in Cite Soleil. This is a poor and crowded neighborhood in Port-au-Prince. Thousands of families had to hide in their homes, unable to get food or water. Dozens of residents were killed by stray bullets. A week of gang violence left at least 89 people dead. An oil terminal that supplies the capital and all of northern Haiti is in Cite Soleil. So, the clashes had a terrible effect on the region's economy.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Haití para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Haití para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |