History of Sparta facts for kids

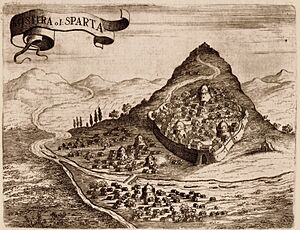

The history of Sparta tells the story of an ancient Greek city-state called Sparta. It was founded by the Dorians, a Greek tribe, and grew to be a very powerful place. This history covers about 1000 years, from its mythical beginnings to when it became part of the Roman Republic in 146 BC. Before the Dorians, other people like the Mycenaeans lived in the Eurotas River valley in Peloponnesus, Greece. Today, Sparta is a region in modern Greece.

Sparta became very strong in the 6th century BC. During the Persian Wars, other Greek city-states saw Sparta as their leader. But after a big earthquake hit Sparta in 464 BC, Athens became suspicious. When Sparta won the Peloponnesian War against Athens, it became the most powerful state in southern Greece. However, Sparta's power was broken after the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC. It never fully got its military strength back and was eventually joined with the Achaean League in the 2nd century BC.

Contents

- Ancient Times in Sparta

- Early Spartan History

- Sparta in the 7th Century BC

- Sparta in the 6th Century BC

- Sparta in the 5th Century BC

- Sparta in the 4th Century BC

- Sparta in the 3rd Century BC

- Sparta Under Rome

- Sparta in Later Periods

- See also

Ancient Times in Sparta

Stone Age Life

The very first signs of people living near Sparta are pieces of pottery from the Middle Neolithic period. These were found about two kilometers southwest of Sparta.

Myths and Legends

According to old myths, the first king of the area, then called Lelegia, was King Lelex. After him came other kings like Eurotas and Lacedaemon. These stories often showed traits that would later be important to Sparta. Famous figures like Helen of Troy and her brothers Castor and Pollux are also part of Sparta's legendary past.

Later, the Achaeans, linked to the Mycenaean civilization, moved in from the north. They took over from the earlier tribes. Eventually, the Heracleidae, often thought to be the Dorians, took control of the land. They founded the city-state of Sparta.

Dorian Arrival

The Mycenaean civilization seemed to decline around the end of the Bronze Age. Then, tribes from the north, called the Dorians, moved into the Peloponnese. They took control of the local tribes and settled there.

Stories say that about 60 years after the Trojan War, the Dorians migrated and led to the rise of classical Sparta. However, these stories were written much later, so some historians doubt how accurate they are.

Sparta's Dark Age

Archaeological finds show that Sparta itself began to be settled around 1000 BC. This was about 200 years after the Mycenaean civilization collapsed. Sparta was made up of four villages. Historians think the two closest to the Acropolis were the first ones. The idea of having two kings might have come from these first two villages joining together.

After the Mycenaean collapse, the population dropped sharply. But then it recovered, especially in Sparta, because it was in a very fertile part of the plain. Between the 8th and 7th centuries BC, Sparta faced a time of disorder and disagreements. Because of this, they made many changes to their society. They believed these changes were started by a wise lawgiver named Lycurgus. These reforms marked the beginning of classical Sparta's history.

Early Spartan History

Lycurgus's Reforms

Most ancient writings say that Lycurgus lived during the reign of King Charillos. Spartans believed their later success came from Lycurgus. He made his reforms when Sparta was weak from internal conflicts and lacked a strong, united community. Some historians even wonder if he was a real person, as his name is linked to the god Apollo.

Some historians suggest that the system of having two kings might have started around this time. This happened when the four villages of Sparta joined together. Other changes, like the creation of the Ephors (officials who watched over the kings), might have been added later but were still credited to Lycurgus.

Sparta Grows in Peloponnesus

The Dorians began expanding Sparta's territory almost as soon as they formed their state. They fought against the Argive Dorians to the east and the Arcadian Achaeans to the northwest. Sparta was naturally protected by its location and was never fortified with walls.

Sparta shared its plain with Amyklai, a strong neighbor to the south. Sparta, under its kings Archelaos and Charillos, moved north to control the upper Eurotas valley. They took over Pharis and Geronthrae. Amyklai probably fell around 750 BC. The people of Geronthrae were likely driven out, while those in Amyklai were simply brought under Spartan rule.

Sparta in the 7th Century BC

The poet Tyrtaeus wrote that the First Messenian War against their western neighbors, the Messenians, lasted 19 years. This war happened around the late 8th or early 7th century BC. For a long time, people doubted if the Second Messenian War really happened, as Herodotus and Thucydides didn't mention it. However, a recently found fragment of Tyrtaeus's writing suggests it did occur, probably in the later 7th century. After this second war, the Messenians were forced into a semi-slave status, becoming helots.

Sparta's control over its eastern regions is less clear. Herodotus said that the Argives once controlled the whole of Cynuria and the island of Cythera. The low population in Cynuria, seen in archaeological findings, suggests that both powers fought over this area. By the end of the Second Messenian War, Sparta had become a major power in the Peloponnesus and the rest of Greece. For centuries after, Sparta's army was known as the best fighting force on land.

Sparta in the 6th Century BC

The Peloponnesian League

In the early 6th century BC, Spartan kings Leon and Agasicles attacked Tegea, a powerful Arcadian city. Sparta didn't succeed at first and lost a battle called the Battle of the Fetters. This defeat changed Sparta's approach. Instead of trying to enslave others, they began building alliances. This led to the creation of the Peloponnesian League. This alliance helped Sparta protect its control over Mesene and gave it freedom to act against Argos.

The Battle of the 300 Champions around 546 BC made Sparta masters of Cynuria, the borderland between Laconia and Argolis. In 494 BC, King Cleomenes I launched a major attack on Argos. Argos didn't fall, but its losses in the Battle of Sepeia weakened its military and caused internal problems. Sparta was now seen as the leading state in Greece and a champion of Greek culture. Many states, including Croesus of Lydia and Plataea, sought Sparta's help or recognized its leadership. When Xerxes invaded, no one questioned Sparta's right to lead the Greek forces on land or sea.

Trips Outside the Peloponnese

At the end of the 6th century BC, Sparta first got involved in affairs north of the Isthmus. In 510 BC, they helped overthrow the Athenian tyrant Hippias. After this, there was disagreement in Athens between Kleisthenes and Isagoras. King Cleomenes I came to Attica with a small army to support Isagoras, who he helped put in power. However, the Athenians soon grew tired of the foreign king and expelled Cleomenes.

Cleomenes then suggested a large expedition of the entire Peloponnesian League to make Isagoras the ruler of Athens. The goals were kept secret, which caused problems. The Corinthians left first, and then a disagreement between Cleomenes and his co-King Demaratos led Demaratos to go home. Because of this failure, Spartans decided not to send both kings with an army in the future. This event also changed the Peloponnesian League. From then on, major decisions were discussed, and Sparta had to get its allies to agree to its plans.

Sparta in the 5th Century BC

The Persian Wars

Battle of Marathon

In 490 BC, Athens asked Sparta for help against the Persians at Marathon. Sparta decided to follow its religious laws and wait until the moon was full to send its army. As a result, Sparta's army arrived at Marathon after the Athenians had already won the battle.

Battle of Thermopylae

Ten years later, in 480 BC, Xerxes led a second Persian invasion. Sparta faced a similar problem. The Persians attacked during the Olympic truce, which Spartans felt they had to respect. Other Greek states were building a large fleet. Sparta decided to send a small force under King Leonidas I to defend Thermopylae. This small group of Spartans, Thespians, and Thebans made a legendary last stand against the huge Persian army. They caused many casualties before being surrounded and defeated.

After Thermopylae, Sparta took a more active role and led the combined Greek forces on land and sea. The important Greek victory at Salamis didn't change Sparta's main problem. They wanted to fight at the Isthmus to avoid their infantry being caught in the open by Persian cavalry.

Battle of Plataea

However, in 479 BC, the remaining Persian forces under Mardonius attacked Attica. Athenian pressure forced Sparta to lead an advance. In the Battle of Plataea, the Greeks, led by the Spartan general Pausanias, defeated the lightly armed Persian infantry. Mardonius was killed. The superior weapons, strategy, and bronze armor of the Greek hoplites and their phalanx proved their worth. Sparta, leading a full Greek alliance, ended Persia's ambition to expand into Europe. Even though this was a pan-Greek victory, Sparta received much credit for its leadership at Thermopylae and Plataea.

Battle of Mycale

In the same year, a united Greek fleet under the Spartan King, Leotychidas, won the Battle of Mycale. This victory led to a revolt of the Ionian Greeks. Sparta did not want them to join the Hellenic alliance. Sparta suggested they leave their homes in Anatolia and settle in cities that had supported the Persians. Athens, however, offered these cities an alliance, which planted the seeds for the Delian League.

In 478 BC, the Greek fleet, led by Pausanias, made moves on Cyprus and Byzantium. But his arrogant behavior led to his recall. Pausanias had upset the Ionians so much that they refused to accept Dorcis, the successor Sparta sent. Instead, those newly freed from Persia turned to Athens. Sources disagree on how Sparta reacted to Athens' growing power. This might show that there were different opinions within Sparta itself. Some Spartans were happy to let Athens take the risk of fighting Persia, while others resented Athens challenging their leadership in Greece.

Later, in classical times, Sparta, along with Athens, Thebes, and Persia, were the main powers fighting for control. After the Peloponnesian War, Sparta, which was traditionally a land power, became a naval power. At its peak, Sparta controlled many key Greek states and even defeated the strong Athenian navy. By the end of the 5th century BC, Sparta had defeated the Athenian Empire and invaded Persian lands in Anatolia. This period is known as the Spartan hegemony.

The Great Sparta Earthquake of 464 BC

The Sparta earthquake in 464 BC caused huge damage to the city. Some historical records say up to 20,000 people died, though modern experts think this number might be too high. The earthquake caused the helots, who were slaves in Spartan society, to revolt.

Events around this revolt increased tension between Sparta and Athens. A treaty between them was even canceled. When Athenian troops sent to help Sparta were sent back, Athenian democracy shifted towards policies that were more against Sparta. This earthquake is seen as a key event that led to the First Peloponnesian War.

Growing Tension with Athens

At this time, Sparta was busy with problems closer to home, like the revolt of Tegea (around 473–471 BC), which was made worse by Argos joining in. But the most serious crisis was the earthquake in 464 BC, which devastated Sparta and killed many people.

Right after the earthquake, the helots saw a chance to rebel. They fortified Ithome and Sparta had to lay siege to it. Cimon, an Athenian who supported Sparta, convinced Athens to send help to put down the rebellion. However, this backfired for the pro-Sparta group in Athens. The Athenian soldiers, who were well-off citizens, were shocked to find that the rebels were Greeks just like them. Sparta began to worry that the Athenian troops might join the rebels. So, the Spartans sent the Athenians home. They said they didn't need Athenian help for a blockade, which was now required. In Athens, this insult led to Athens breaking its alliance with Sparta and instead allying with Sparta's enemy, Argos. Further problems arose as Athenian democracy grew stronger under Ephialtes and Pericles.

Some historians believe that the helot revolt led Spartans to change their army. They started including non-citizens, called perioeci, in their citizen soldier groups. This was unusual for Greece. However, others doubt that Sparta ever only used citizens as soldiers.

The Peloponnesian Wars

The Peloponnesian Wars were long conflicts fought on land and sea in the last half of the 5th century BC. They were between the Delian League, led by Athens, and the Peloponnesian League, led by Sparta. Both sides wanted control over other Greek city-states. The Delian League is often called "the Athenian Empire" by scholars. The Peloponnesian League believed it was defending itself against Athens' growing power.

The war often had ethnic differences: the Delian League included Athenians and Ionians, while the Peloponnesian League was mostly Dorians. However, the Boeotians, a third power, sided with the Peloponnesian League but were never fully trusted by Sparta. The reasons for the war were complex, including local politics and wealth. In the end, Sparta won, but its power soon declined. It then got into wars with Boeotia and Persia, until it was finally defeated by Macedon.

First Peloponnesian War

When the First Peloponnesian War started, Sparta was still busy putting down the helot revolt. So, its involvement was not very strong. It mostly involved small expeditions, like helping to defeat the Athenians at the Battle of Tanagra in 457 BC in Boeotia. However, Sparta then went home, giving Athens a chance to defeat the Boeotians at the battle of Oenophyta and take control of Boeotia.

When the helot revolt finally ended, Sparta needed a break. They sought and got a five-year truce with Athens. But Sparta also made a thirty-year peace with Argos to ensure they could fight Athens without problems. So, Sparta was able to take full advantage when Megara, Boeotia, and Euboea revolted, sending an army into Attica. The war ended with Athens losing its mainland lands but keeping its large Aegean Empire. Both of Sparta's Kings were exiled for letting Athens regain Euboea, and Sparta agreed to a Thirty Year Peace. But this treaty was broken when Sparta went to war with Euboea.

Second Peloponnesian War

Within six years, Sparta suggested to its allies that they go to war with Athens to support a rebellion in Samos. This time, Corinth successfully argued against Sparta, and the idea was voted down. When the Peloponnesian War finally started in 431 BC, the main public complaint against Athens was its alliance with Corinth's enemy Korkyra and Athens' treatment of Potidea. However, according to Thucydides, the real reason for the war was Sparta's fear of Athens' growing power. The Second Peloponnesian War, fought from 431–404 BC, became the longest and most costly war in Greek history.

Archidamian War

Sparta entered the war saying its goal was to "free the Greeks." This meant completely defeating Athens. Their plan was to invade Attica hoping to make Athens come out and fight. Athens, however, planned a defensive war. Athenians would stay inside their strong walls and use their powerful navy to attack the Spartan coast. In 425 BC, a group of Spartans surrendered to the Athenians at Pylos, which made people doubt Sparta's ability to win. This was helped by Brasidas's trip to Thrace, an area where Athens' lands could be reached by land. This led to a compromise in 421 BC called the Peace of Nicias. The war between 431 and 421 BC is called the "Archidamian War" after the Spartan king who invaded Attica at the start, Archidamus II.

The Sicilian Expedition

The war started again in 415 BC and lasted until 404 BC. In 415 BC, Athens decided to capture Syracuse, a colony of Dorian Corinth. The Athenian assembly believed it would be a profitable possession and make their empire stronger. They spent a lot of state money on a military expedition. But one of their commanders, Alcibiades, was called back on a false charge of disrespecting religion. He faced the death penalty. He escaped on his ship and went to Sparta. He was found guilty without being present and sentenced to death.

At first, Sparta hesitated to start fighting again. In 414 BC, a combined force of Athenians and Argives attacked the Laconian coast. After this, Sparta began to follow Alcibiades' advice. Sparta's success and the eventual capture of Athens in 404 BC were partly due to his advice. He convinced Sparta to send Gylippus to defend Syracuse, to fortify Decelea in northern Attica, and to actively help Athenian allies revolt. The next year, Spartans marched north, fortified Deceleia, cut down all the olive groves (Athens' main cash crop), and stopped Athenians from using the countryside. Athens now depended completely on its fleet, which was stronger than Sparta's navy at the time. Spartan generals, however, were not good at naval warfare and were often unskilled or cruel.

Gylippus did not arrive alone at Syracuse. He gathered a large force from Sicily and Spartan soldiers serving overseas and took command of the defense. The first Athenian force under Nicias had sailed bravely into the Great Harbor of Syracuse to set up camp. Gylippus gathered an international army of pro-Spartan groups from many parts of the eastern Mediterranean. He said they were fighting to free Greece from Athens' control. The Athenian force was not big enough to properly besiege the city. They tried to build a wall around the city but were stopped by a counter-wall. A second army under Demosthenes arrived. Finally, the Athenian commanders risked everything on one attack against a weak point, but they were pushed back with heavy losses. They were about to leave for Athens when an eclipse of the full moon made their religious advisors insist they stay for nine more days. This was just enough time for the Syracusans to prepare a fleet to block the harbor mouth.

Events quickly turned into a disaster for the Athenians. They tried to break out of the harbor but were defeated in a naval battle. The admiral, Eurymedon, was killed. Losing hope, they abandoned their remaining ships and the wounded and tried to march out by land. The route was blocked at every crossing by Syracusans. The Athenian army marched under a rain of attacks. When Nicias accidentally marched ahead of Demosthenes, the Syracusans surrounded Demosthenes and forced him to surrender. Nicias soon surrendered too. Both leaders were executed, even though Gylippus wanted to take them back to Sparta. Thousands of prisoners were held in quarries without basic needs or removal of the dead. After several months, the remaining Athenians were ransomed. The failure of this expedition in 413 BC was a huge loss for Athens, but the war continued for another ten years.

Persian Help

Sparta's weaknesses at sea were clear by this time, especially with Alcibiades' teaching. Persia helped Sparta by providing large amounts of money, which was crucial for Sparta's navy. In 412 BC, agents of Tissaphernes, the Persian governor, approached Sparta with a deal. The Persian king would give money for the Spartan fleet if Sparta promised him the lands he considered his ancestors' – the coast of Asia Minor with the Ionian cities. An agreement was made. A Spartan fleet and a negotiator, Alcibiades, were sent to Asia Minor. Alcibiades was no longer welcome in Sparta because of his new mistress, the wife of King Agis. After becoming friends with Tissaphernes, Alcibiades was secretly offered an honorable return to Athens if he would influence Tissaphernes on Athens' behalf. He was a double agent from 411–407 BC. The Spartans received little money or good advice.

By 408 BC, the Persian king realized the agreement with Sparta was not being followed. He sent his brother, Cyrus the younger, to take over from Tissaphernes in Lydia. Tissaphernes was moved to Caria. Alcibiades, now exposed, left for Athens in 407 BC. In his place, Sparta sent a skilled agent, Lysander, a friend of King Agis. Lysander was an excellent diplomat and organizer, though he was also arrogant and dishonest. He and Cyrus got along well. The Spartan fleet quickly improved. In 406 BC, Alcibiades returned as commander of an Athenian squadron, hoping to destroy the new Spartan fleet, but it was too late. Lysander defeated him at the Battle of Notium. The suspicious Athenian government rejected its agreement with Alcibiades. He went into exile again, living in a remote villa in the Aegean, now without a country.

Lysander's time as naval commander ended. He was replaced by Callicratidas, but Cyrus now limited his payments for the Spartan fleet. The money from the Persian king had run out. After Callicratides' defeat and death at the Battle of Arginusae, the Spartans offered peace on generous terms. The Delian League would remain. Athens would still be allowed to collect tribute for its defense. However, the war party in Athens did not trust Sparta. One of its leaders, Cleophon, demanded that the Spartans withdraw from all cities they held as a condition for peace. The assembly rejected the Spartan offer. Athens then launched a new attack against Spartan allies in the Aegean.

In the winter of 406/405 BC, those allies met with Cyrus at Ephesus. Together, they asked Sparta to send Lysander for a second term. Spartan rules and their constitution should have prevented this, but after the new Spartan defeat, a way around it was found. Lysander would be the secretary of a nominal naval commander, Aracus, with the rank of vice-admiral. Lysander was again given all the resources needed to maintain and operate the Spartan fleet. Cyrus provided the funds from his own money. The Persian king then called Cyrus back to answer for executing some members of the royal family. Cyrus appointed Lysander governor in his place, giving him the right to collect taxes. This trust was justified in 404 BC when Lysander destroyed the Athenian fleet at the Battle of Aegospotami.

Lysander then sailed easily to Athens to blockade it. If he met a state from the Delian League on his way, he gave the Athenian garrison the option to withdraw to Athens. If they refused, they were treated harshly. He replaced democracies with pro-Spartan governments of 10 men, led by a Spartan governor.

Athens Surrenders

After the Battle of Aegospotami, the Spartan navy sailed wherever it wanted without opposition. A fleet of 150 ships entered the Saronic Gulf to blockade Piraeus, Athens' port. Athens was cut off. In the winter of 404 BC, the Athenians sent a group to King Agis at Deceleia. They offered to become a Spartan ally if they could keep their city walls. He sent them to Sparta. The Spartan officials, called ephors, turned the group back, saying they should return with better terms.

The Athenians then chose Theramenes to talk with Lysander, but Lysander made himself unavailable. Theramenes found him, probably on Samos. After waiting three months, he returned to Athens, saying Lysander had delayed him and that he had to negotiate directly with Sparta. A group of nine delegates was chosen to go with Theramenes to Sparta. This time, the group was allowed to pass.

The fate of Athens was then discussed in the Spartan assembly. This assembly could debate, veto, and propose new ideas. The people in the assembly had the final say. Corinth and Thebes suggested that Athens be destroyed and its land turned into pasture for sheep. Agis, supported by Lysander, also recommended destroying the city. But the assembly refused. They said they would not destroy a city that had helped Greece so much in the past, referring to Athens' role in defeating the Persians.

Instead, the Athenians were offered terms of unconditional surrender: the long walls must be torn down, Athens must leave all states of the Delian League, and Athenian exiles must be allowed to return. The Athenians could keep their own land. The returning delegates found the people of Athens starving. The surrender was accepted in April 404 BC, 27 years after the war began, with little opposition. A few weeks later, Lysander arrived with a Spartan army. They began to tear down the walls to the sound of pipes played by young female musicians. Lysander reported to the ephors that "Athens is taken." The ephors complained that he used too many words, saying "taken" would have been enough.

Some modern historians suggest a less kind reason for Sparta's mercy: they needed Athens as a balance against Thebes. However, some historians doubt that Spartans could have predicted Thebes would become a serious threat later. Lysander's political rivals might have defended Athens not out of gratitude, but because they feared making Lysander too powerful.

The Thirty Tyrants

In the spring of 404 BC, the surrender terms required Athenians to tear down the long walls between the city and the port of Piraeus. When internal disagreements stopped Athenians from forming a government, Lysander ended the democracy. He set up a government of 30 oligarchs, who became known as the Thirty Tyrants. These men supported Sparta. They were initially voted into power to write down laws, but they immediately asked the Spartan army to arrest their enemies. They killed people who supported democracy and took their property.

Sparta's allies in the Peloponnesian League were uneasy. Boeotia, Elis, and Corinth defied Sparta by offering refuge to those who opposed the Thirty. Lysander left Athens to set up similar governments of 10 men in other parts of the former Athenian Empire. He left the Spartan army in Athens under the command of the Thirty. Taking advantage of general anger against Sparta and a change to an anti-Spartan government in Boeotia, exiles and non-Athenian supporters (who were promised citizenship) attacked Athens from Boeotia under Thrasybulus. In the Battle of Phyle, followed by the Battle of Munichia and the Battle of Piraeus, they defeated the Athenian supporters of the Thirty. The Spartan army regained partial control of Athens and set up a government of 10 men.

Athens was on the edge of civil war. Both sides sent representatives to present their case to King Pausanias. The Thirty spoke first. They complained that Piraeus was controlled by a Boeotian puppet government. Pausanias immediately appointed Lysander as governor, with the approval of the ephors. He ordered Lysander to Sparta with his brother, who had been made naval commander over 40 ships. They were to put down the rebellion and expel the foreigners.

After the Ten had been fully heard, Pausanias, with the agreement of three out of five ephors, went to Athens himself. He brought a force including men from all allies except Boeotia and Corinth, who were suspected. He met and took over from Lysander on the road. A battle followed against Thrasybulus. His forces killed two Spartan commanders but were eventually driven into a marsh and trapped. Pausanias stopped the fighting. He set up a board of 15 peace commissioners that had been sent with him by the Spartan assembly and invited both sides to a meeting. The final agreement restored democracy to Athens. The Thirty held Eleusis, as they had previously killed everyone there. It was made independent of Athens as a safe place for supporters of the Thirty. A general pardon was declared. The Spartans ended their occupation.

The former oligarchs rejected the peace. After failing to get help from other Greek states, they tried a coup. Facing the new Athenian state with overwhelming odds, they were tricked into a meeting, captured, and executed. Eleusis returned to Athens. Sparta refused further involvement. Meanwhile, Lysander, who had been called back to Sparta, with the help of King Agis, accused Pausanias of being too lenient with the Athenians. Not only was Pausanias found innocent by a large majority of the judges (except for Agis's supporters), including all five ephors, but the Spartan government also rejected all the governments of 10 men that Lysander had set up in former Athenian Empire states and ordered the old governments restored.

Sparta in the 4th Century BC

Spartan Power

In the 5th century BC, Athens and Sparta were the two main powers in the eastern Mediterranean. Sparta's victory over Athens led to Sparta being the most powerful state in the early 4th century BC.

Failed Persian Intervention

Sparta had a close relationship with Cyrus the Younger. They secretly supported his attempt to take the Persian throne. After Cyrus was killed at the Battle of Cunaxa, Sparta briefly tried to be friendly with Artaxerxes II, the Persian king. However, in late 401 BC, Sparta decided to help several Ionian cities and sent an army to Anatolia. Although the war was fought for Greek freedom, Sparta's defeat at the Battle of Cnidus in 394 BC was welcomed by many Greek cities in the region. Even though Persian rule meant paying taxes, it seemed better than Spartan rule.

The King's Peace

At the end of 397 BC, Persia sent an agent from Rhodes with gifts to Sparta's opponents in mainland Greece. These gifts mainly encouraged those who already resented Sparta. Sparta made the first aggressive move, using Boeotia's support for its ally Locris against Sparta's ally Phocis as an excuse. An army under Lysander and Pausanias was sent. Lysander went ahead and was killed at the Battle of Haliartus. When Pausanias arrived, instead of avenging the defeat, he simply asked for a truce to bury the bodies. For this, Pausanias was put on trial and went into exile.

At the Battle of Coronea, Agesilaus I, the new king of Sparta, had a slight advantage over the Boeotians. At Corinth, the Spartans kept their position. However, they felt they needed to end Persian hostility and use Persian power to strengthen their own position at home. So, they made the humiliating Peace of Antalcidas with Artaxerxes II in 387 BC. By this treaty, they gave the Greek cities on the Asia Minor coast and Cyprus back to the Persian King. The treaty also stated that all other Greek cities should be independent. Finally, Sparta and Persia were given the right to make war on those who did not respect the terms. Sparta enforced a very one-sided interpretation of independence. The Boeotian League was broken up, but the Spartan-controlled Peloponnesian League was not. Also, Sparta did not think independence meant a city could choose democracy over Sparta's preferred government. In 383 BC, a request from two cities in Chalkidike and the King of Macedon gave Sparta an excuse to break up the Chalkidian League led by Olynthus. After several years of fighting, Olynthus was defeated, and the cities of Chalkidike joined the Peloponnesian League. Looking back, the real winner of this conflict was Philip II of Macedon.

A New Civil War

During the Corinthian War, Sparta faced a group of leading Greek states: Thebes, Athens, Corinth, and Argos. Persia initially supported this alliance because Sparta had invaded its lands in Anatolia and Persia feared further Spartan expansion. Sparta won several land battles, but many of its ships were destroyed at the battle of Cnidus by a Greek-Phoenician mercenary fleet provided by Persia to Athens. This severely damaged Sparta's naval power but did not end its hopes of invading Persia further, until Conon the Athenian attacked the Spartan coast and brought back the old Spartan fear of a helot revolt.

After a few more years of fighting, the Peace of Antalcidas was established in 387 BC. This treaty stated that all Greek cities in Ionia would return to Persian control, and Persia's Asian border would be free from the Spartan threat. The war's effects were to confirm Persia's ability to successfully interfere in Greek politics and to show Sparta's weakened leading position in the Greek political system.

In 382 BC, Phoebidas, leading a Spartan army north against Olynthus, took a detour to Thebes and seized the Kadmeia, the citadel of Thebes. The leader of the anti-Spartan group was executed after a quick trial, and a small group of pro-Spartan supporters was put in power in Thebes and other Boeotian cities. This was a clear violation of the Peace of Antalcidas. Seizing the Kadmeia led to the Theban rebellion and the start of the Boeotian War. Sparta started this war with the advantage, but failed to achieve its goals. Early on, a failed attack on Piraeus by the Spartan commander Sphodrias weakened Sparta's position by pushing Athens into an alliance with Thebes. Sparta then lost battles at sea (the Battle of Naxos) and on land (the Battle of Tegyra) and could not stop the re-establishment of the Boeotian League and the creation of the Second Athenian League.

The Peace of Callias

In 371 BC, a new peace meeting was called in Sparta to approve the Peace of Callias. Again, the Thebans refused to give up their control over Boeotia. So, the Spartans sent a force under King Cleombrotus to try and make Thebes accept. When the Thebans fought at Leuctra, it was more out of brave desperation than hope. However, Sparta was defeated, and King Cleombrotus was killed. This was a huge blow to Sparta's military reputation. The result of the battle was that power shifted from Sparta to Thebes.

Fewer Citizens

Because Spartan citizenship was passed down through families, Sparta faced a growing problem: the helot population greatly outnumbered its citizens. The worrying decrease in Spartan citizens was noted by Aristotle, who saw it as a sudden event. While some researchers think it was due to war deaths, it seems the number of citizens steadily dropped by 50% every fifty years, regardless of battles. This was likely due to wealth shifting among citizens, which became clear when laws allowed citizens to give away their land.

Facing Theban Power

Sparta never fully recovered from its losses at Leuctra in 371 BC and the helot revolts that followed. Still, it remained a regional power for over two centuries. Neither Philip II nor his son Alexander the Great tried to conquer Sparta itself.

By the winter of late 370 BC, King Agesilaus went to battle, not against Thebes, but to try and keep some influence for Sparta in Arkadia. This backfired when Arkadians asked Boeotia for help. Boeotia responded by sending a large army, led by Epaminondas. This army first marched on Sparta itself and then moved to Messenia, where the helots had already rebelled. Epaminondas made that rebellion permanent by fortifying the city of Messene.

The final major battle was in 362 BC. By this time, some of Boeotia's former allies, like Mantinea and Elis, had joined Sparta. Athens also fought with Sparta. Boeotia and its allies won the Battle of Mantinea, but Epaminondas was killed during the victory. After the battle, both Sparta's enemies and allies agreed to a common peace. Only Sparta refused because it would not accept Messenia's independence.

Facing Macedon

Sparta had neither the men nor the money to regain its lost power. The continued existence of independent Messenia and Arcadia on its borders kept Sparta constantly worried for its own safety. Sparta did join Athens and Achaea in 353 BC to stop Philip II of Macedon from passing Thermopylae and entering Phocis. But beyond this, Sparta did not take part in Greece's struggle with the new power that had grown on its northern borders. The final showdown saw Philip fighting Athens and Thebes at Chaeronea. Sparta was held back at home by Macedonian allies like Messene and Argos and did not participate.

After the Battle of Chaeronea, Philip II of Macedon entered the Peloponnese. Sparta alone refused to join Philip's "Corinthian League." But Philip arranged for some border areas to be given to the neighboring states of Argos, Arcadia, and Messenia.

During Alexander's campaigns in the east, the Spartan king, Agis III, sent a force to Crete in 333 BC to secure the island for Sparta. Agis then took command of allied Greek forces against Macedon. He had early successes before besieging Megalopolis in 331 BC. A large Macedonian army under general Antipater marched to relieve it and defeated the Spartan-led force in a major battle. More than 5,300 Spartans and their allies were killed, and 3,500 of Antipater's troops. Agis, wounded and unable to stand, ordered his men to leave him behind to face the advancing Macedonian army. He wanted to buy them time to retreat. On his knees, the Spartan king killed several enemy soldiers before finally being killed. Alexander was merciful and only forced the Spartans to join the League of Corinth, which they had previously refused.

The memory of this defeat was still fresh in Spartan minds when the general revolt against Macedonian rule, known as the Lamian War, broke out. Because of this, Sparta stayed neutral.

Even as it declined, Sparta never forgot its claim to be the "defender of Hellenism" and its famous Laconic wit. One story says that when Philip II sent a message to Sparta saying, "If I invade Laconia, I shall turn you out," the Spartans replied with the single, short answer: αἴκα, meaning "if."

When Philip created the league of the Greeks to unite Greece against Persia, the Spartans chose not to join. They were not interested in joining a pan-Greek expedition if it wasn't under Spartan leadership. So, after conquering Persia, Alexander the Great sent 300 suits of Persian armor to Athens with this inscription: "Alexander, son of Philip, and all the Greeks except the Spartans, give these offerings taken from the foreigners who live in Asia. "

Sparta in the 3rd Century BC

During Demetrius Poliorcetes’ campaign to conquer the Peloponnese in 294 BC, the Spartans, led by Archidamus IV, tried to resist but were defeated in two battles. If Demetrius hadn't decided to focus on Macedonia, the city would have fallen. In 293 BC, a Spartan force under Cleonymus encouraged Boeotia to challenge Demetrius, but Cleonymus soon left, leaving Thebes in trouble. In 280 BC, a Spartan army, led by King Areus, marched north again. This time, they claimed to be saving sacred land near Delphi from the Aetolians. However, they damaged their moral standing by looting the area. It was then that the Aetolians caught and defeated them.

In 272 BC, Cleonymus of Sparta (who had been replaced as King by Areus) convinced Pyrrhus to invade the Peloponnese. Pyrrhus laid siege to Sparta, confident he could easily take the city. However, the Spartans, with even the women helping in the defense, managed to fight off Pyrrhus's attacks. At this point, Pyrrhus received a request from an opposing Argive group for support against the pro-Gonatas ruler of Argos, and he withdrew from Sparta. In 264 BC, Sparta formed an alliance with Athens and Ptolomeic Egypt (along with several smaller Greek cities) to try and break free from Macedon. During the resulting Chremonidean War, the Spartan King Areus led two expeditions to the Isthmus, where Corinth was guarded by Macedonia. He was killed in the second. When the Achaean League expected an attack from Aetolia, Sparta sent an army under Agis to help defend the Isthmus. But the Spartans were sent home when it seemed no attack would happen. Around 244 BC, an Aetolian army raided Laconia, reportedly taking 50,000 captives, though this is likely an exaggeration.

During the 3rd century BC, a social crisis slowly appeared. Wealth became concentrated among about 100 families. The number of equal citizens (who formed the backbone of the Spartan army) fell to 700. This was less than a tenth of its peak of 9000 in the 7th century BC. Agis IV was the first Spartan king to try reforms. His plan included canceling debts and changing land ownership. Opposition from King Leonidas was removed when he was deposed on shaky grounds. However, Agis IV's opponents took advantage of a time when he was away from Sparta. When he returned, he faced a very unfair trial.

The next attempt at reform came from Cleomenes III, King Leonidas's son. In 229 BC, Cleomenes attacked Megalopolis, starting a war with Achaea. Aratus, who led the Achaean League forces, used a very cautious strategy, even though he had 20,000 men to Cleomenes' 5,000. Cleomenes faced obstacles from the Ephors, which probably showed a general lack of enthusiasm among Sparta's citizens. Nevertheless, he defeated Aratus. With this success, he left the citizen troops in the field and, with mercenaries, marched on Sparta to stage a coup. The ephorate was abolished; indeed, four out of five of them had been killed during Cleomenes' takeover. Land was redistributed, allowing more people to become citizens. Debts were canceled. Cleomenes gave Sphaerus, his Stoic advisor, the job of bringing back the old strict training and simple life. Historian Peter Green notes that giving such a responsibility to a non-Spartan showed how much Sparta had lost its Lycurgian traditions. These reforms angered the wealthy people of the Peloponnese, who feared social revolution. For others, especially the poor, Cleomenes brought hope. This hope quickly faded when Cleomenes started taking cities, and it became clear that social reform outside Sparta was not his main goal.

Cleomenes' reforms aimed to restore Spartan power. Initially, Cleomenes was successful, taking cities that had been part of the Achaean League and getting financial support from Egypt. However, Aratus, the leader of the Achaean League, decided to ally with Achaea's enemy, Macedonia. With Egypt cutting financial aid, Cleomenes decided to risk everything on one battle. In the resulting Battle of Sellasia in 222 BC, Cleomenes was defeated by the Achaeans and Macedonia. Antigonus III Doson, the king of Macedon, formally entered Sparta with his army, something Sparta had never experienced before. The ephors were restored, while the kingship was suspended.

At the beginning of the Social War in 220 BC, envoys from Achaea unsuccessfully tried to convince Sparta to fight against Aetolia. Aetolian envoys were also unsuccessful at first. But their presence was used as an excuse by Spartan royalists who staged a coup that brought back the dual kingship. Sparta then immediately entered the war on Aetolia's side.

Sparta Under Rome

The information about Nabis, who took power in 207 BC, is very negative. So, it's hard to know today if the accusations against him are true. People said his reforms were only for his own benefit. His reforms certainly went much deeper than those of Cleomenes, who had freed 6,000 helots only as an emergency measure.

The Encyclopædia Britannica says:

Historian W.G. Forest accepts these accusations, including that Nabis murdered his ward and was involved in state-sponsored piracy and banditry. But he doesn't believe Nabis's motives were entirely selfish. He sees Nabis as a ruthless version of Cleomenes, genuinely trying to solve Sparta's social crisis. Nabis started building Sparta's first walls, which were about 6 miles long.

At this point, Achaea switched its alliance from Macedon to Rome. Since Achaea was Sparta's main rival, Nabis leaned towards Macedonia. It was becoming harder for Macedonia to hold Argos, so Philip V of Macedon decided to give Argos to Sparta. This increased tension with the Achaean League. Still, he was careful not to break his alliance with Rome. After the wars with Philip V ended, Sparta's control of Argos went against Rome's official policy of freedom for the Greeks. So, Titus Quinctius Flamininus organized a large army and invaded Laconia, besieging Sparta. Nabis was forced to give up. He had to leave all his possessions outside Laconia, surrender the Laconian seaports and his navy, and pay a large fine of 500 talents. Freed slaves were returned to their former masters.

Even though the territory he controlled was now only the city of Sparta and its immediate surroundings, Nabis still hoped to regain his former power. In 192 BC, seeing that the Romans and their Achaean allies were busy with an upcoming war with King Antiochus III of Syria and the Aetolian League, Nabis tried to recapture the harbor city of Gythium and the Laconian coastline. At first, he succeeded, capturing Gythium and defeating the Achaean League in a small naval battle. Soon after, however, his army was defeated by the Achaean general Philopoemen and trapped within Sparta's walls. After damaging the surrounding countryside, Philopoemen returned home.

Within a few months, Nabis asked the Aetolian League to send troops to protect his territory against the Romans and the Achaean League. The Aetolians sent an army to Sparta. Once there, however, the Aetolians betrayed Nabis, killing him while he was training his army outside the city. The Aetolians then tried to take control of the city, but were stopped by an uprising of the citizens. The Achaeans, wanting to take advantage of the chaos, sent Philopoemen to Sparta with a large army. Once there, he forced the Spartans to join the Achaean League, ending their independence.

Sparta did not actively participate in the Achaean War in 146 BC, when the Achaean League was defeated by the Roman general Lucius Mummius. Afterward, Sparta became a free city in the Roman sense. Some of Lycurgus's institutions were restored, and the city became a tourist attraction for wealthy Romans who came to see exotic Spartan customs. The former Perioeci communities were not returned to Sparta. Some of them were organized as the "League of Free Laconians".

After 146 BC, information about Spartan history is somewhat scattered. Pliny said its freedom was empty, though Chrimes argues that while this might be true for foreign relations, Sparta kept a high level of independence in internal matters.

A passage in Suetonius shows that the Spartans were allies of the powerful patrician family of the Claudii. Octavian's wife Livia was a member of the Claudii. This might explain why Sparta was one of the few Greek cities that supported Octavian first in the war against Brutus and Cassius in 42 BC, and then in the war against Mark Antony in 30 BC.

During the late 1st century BC and much of the 1st century AD, Sparta was controlled by the powerful Euryclids family. They acted like a "client-dynasty" for the Romans. After the Euryclids lost favor during the reign of Nero, the city was ruled by republican institutions, and civic life seemed to thrive. In the 2nd century AD, a 12-kilometer-long aqueduct was built.

The Romans used Spartan auxiliary troops in their wars against the Parthians under emperors Lucius Verus and Caracalla. It is likely that the Romans wanted to use the legend of Spartan bravery. After an economic decline in the 3rd century, urban prosperity returned in the 4th century. Sparta even became a small center for higher learning, as shown in some letters by Libanius.

Sparta in Later Periods

Sparta During the Migration Period

In 396 AD, Alaric attacked Sparta. Although it was rebuilt, the revived city was much smaller. The city was finally abandoned during this period when many towns in the Peloponnese were raided by an Avaro-Slav army. Some Proto-Slavic tribes settled around this time. The extent of Slavic invasions and settlement in the late 6th and especially 7th centuries is still debated. The Slavs occupied most of the Peloponnese, except for the eastern coast, which remained under Byzantine control.

Under Nikephoros I, after a Slavic revolt and attack on Patras, a strong effort was made to make the region more Greek. According to the Chronicle of Monemvasia, in 805, the Byzantine governor of Corinth fought the Slavs, defeated them, and allowed the original inhabitants to reclaim their lands. They regained control of Patras, and the peninsula was resettled with Greeks. Many Slavs were moved to Asia Minor, and many Greeks from Asia, Sicily, and Calabria were resettled in the Peloponnese. The entire peninsula became the new thema of Peloponnesos, with its capital at Corinth. There was also a continuous Greek population in the Peloponnese. With this re-Hellenization, the Slavs likely became a minority among the Greeks. By the end of the 9th century, the Peloponnese was culturally and administratively Greek again, except for a few small Slavic tribes in the mountains.

According to Byzantine sources, the Mani Peninsula in southern Laconia remained pagan until well into the 10th century. Emperor Constantine Porphyrogennetos also claimed that the Maniots kept their independence during the Slavic invasion and that they are descended from the ancient Greeks. Doric-speaking people still live in Tsakonia today. During the Middle Ages, the political and cultural center of Laconia moved to the nearby settlement of Mystras.

Sparta in the Late Middle Ages

When the Frankish Crusaders arrived in Morea, they found a fortified city called Lacedaemonia (Sparta) on part of the ancient Sparta site. This city continued to exist, though with fewer people, even after the Prince of Achaea William II Villehardouin founded the fortress and city of Mystras in 1249. Mystras was on a spur of Taygetus, about 3 miles northwest of Sparta.

Mystras soon fell into the hands of the Byzantines and became the center of the Despotate of the Morea. This lasted until the Ottoman Turks under Mehmed II captured it in 1460. In 1687, it came into the possession of the Venetians. The Turks took it back in 1715. So, for nearly six centuries, Mystras, not Sparta, was the main focus of Laconian history.

In 1777, after the Orlov events, some people from Sparta with the name "Karagiannakos" (Greek: Καραγιάννακος) moved to Koldere, near Magnesia.

The Mani Peninsula region of Laconia kept some independence during the Ottoman period. It played an important role in the Greek War of Independence.

Modern Sparta

Until modern times, the site of ancient Sparta was a small town with a few thousand people. They lived among the ruins, overshadowed by Mystras, a more important medieval Greek settlement nearby. The Palaiologos family (the last Byzantine Greek imperial dynasty) also lived in Mystras. In 1834, after the Greek War of Independence, King Otto of Greece ordered that the town be expanded into a city.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Esparta para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Esparta para niños

- List of Kings of Sparta

- Spartan army

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |