History of Toulouse facts for kids

Toulouse is a city in southern France with a very long and interesting history. It's located in a region called Occitania. The city's story goes back to ancient times, even before the Romans arrived. After the powerful Roman Empire, Toulouse was ruled by the Visigoths and then by different groups of Franks, including the Merovingian and Carolingian families. During the Middle Ages, Toulouse was the capital of the County of Toulouse. Today, it is an important city and the capital of the Midi-Pyrénées region.

Contents

- Early Settlements: Before Roman Times

- Roman Rule: From 118 BC to AD 418

- Visigothic Kingdom: From 418 to 508

- Frankish Rule: From 508 to 768

- Carolingian Franks: From 768 to 877

- Rise of the County of Toulouse: From 877 to 10th Century

- Toulouse in the 11th Century

- Toulouse in the 12th Century

- Toulouse in the 13th Century

- Toulouse in the 13th to 14th Centuries

- Toulouse in the 15th to 16th Centuries

- Toulouse in the 17th Century

- Toulouse in the 18th Century

- Toulouse in the 19th Century

- Toulouse in the 21st Century

- See also

Early Settlements: Before Roman Times

Archaeologists have found signs that people lived in Toulouse as early as 800 BC. The city's location was perfect! The Garonne River makes a bend here, making it easy to cross. People settled on hills overlooking the river, in a place now called Vieille-Toulouse (which means "Old-Toulouse"). This spot was great for farming and became a busy trading center. Goods moved between the Pyrenees mountains, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Atlantic Ocean.

The city's old name, Tolosa, has stayed almost the same for centuries. This is quite rare for a French city, even after many invasions! The first people living here were likely the Aquitani. Later, Iberians came from the south. Around 300 BC, a Gallic tribe called the Volcae Tectosages arrived. They settled in Tolosa and mixed with the local people. By 200 BC, Tolosa was known as an important capital. Experts believe it was one of the richest cities in Gaul before the Romans. Gold and silver mines were nearby, and its temples collected a lot of wealth.

Roman Rule: From 118 BC to AD 418

The Romans started taking over southern Gaul around 125 BC. In 118 BC, they founded a new city called Narbo Martius (Narbonne). They soon met the people of Tolosa, who were known for their wealth and good trading location. Tolosa became an ally of the Romans. The Romans built a fort nearby but mostly left Tolosa to manage itself.

Around 109 BC, a Germanic tribe called the Cimbri invaded. The Tolosates rebelled against Rome. But Rome soon recovered and defeated the invaders. In 106 BC, a Roman general named Quintus Servilius Caepio recaptured Tolosa. He took the city's wealth from its temples.

Tolosa then became part of the Roman province called Provincia. At first, it was a military outpost. But after Julius Caesar conquered all of Gaul, Tolosa was no longer just a military base. It became a busy trading hub between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, and it grew quickly.

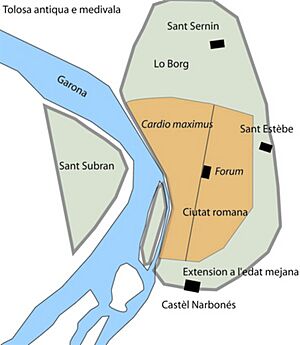

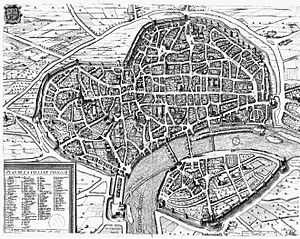

A big change happened when the city moved north of the hills. A new Roman city, with straight streets, was built around 10–30 AD. Everyone had to move to this new city, also called Tolosa. Walls were built around it, showing its importance. Tolosa became a major city in the Roman Empire.

During a civil war after Emperor Nero's death, a man from Tolosa, M. Antonius Primus, helped a new emperor, Vespasian, come to power. Because of this, Emperor Domitian gave Tolosa the special title of "Roman colony." He also called it "Palladia" after Pallas Athena, the goddess of arts and knowledge.

Palladia Tolosa was a grand Roman city. It had aqueducts, a circus, theaters, public baths (thermae), a forum, and a good sewage system. It was safe from invasions in the 3rd century. Toulouse became the fourth-largest city in the western Roman Empire. Around this time, Christianity arrived. Saint Saturnin, the first bishop of Toulouse, was martyred around 250 AD. In 313, Christians gained religious freedom. The Saint-Sernin basilica opened in 403 to honor Saint Saturnin.

In 406, tribes crossed the Rhine River. In 407, the Vandals besieged Toulouse. But under its bishop, Saint Exuperius, the city held strong. The Vandals left. In 413, the Visigoths captured Toulouse but soon left. In 418, the Roman Emperor Honorius gave the Visigoths Aquitania and Toulouse. The Visigoths chose Palladia Tolosa as their capital, ending Roman rule.

Visigothic Kingdom: From 418 to 508

The Visigothic kings of Toulouse were allies of the Roman Empire. They started to take over nearby lands. They helped defeat other Germanic invaders in Spain and expanded their territory. In 451, the Visigoths helped Rome defeat the Huns. In 455, a Roman official named Avitus was declared the new Roman emperor in Toulouse by his Visigothic friends. His rule was short, which made the Visigoths angry. They fought Rome, and a weaker Rome gave in.

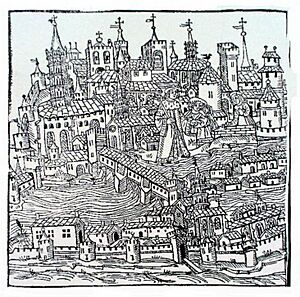

King Euric (466–484) was an enemy of Rome. In 475, he declared his kingdom independent, just a year before the Western Roman Empire fell. Toulouse became the capital of a growing Gothic kingdom. By the end of the 5th century, this kingdom stretched from the Loire Valley in the north to the Strait of Gibraltar in the south. It was the largest area ever controlled from Toulouse.

Unlike many cities in western Europe, Toulouse stayed rich and busy during this time. The Visigoths were Arian Christians, which was different from the local Gallo-Roman people. But they were generally well-liked because they brought protection and wealth. The city kept its old walls, which was unusual for the time. The Visigoths mixed Roman and Gothic cultures. They even kept Roman law in their kingdom. Their government was more organized than the Frankish kingdom to the north.

Under Clovis, the Franks became Catholic. They got support from bishops who didn't like the Visigoths' Arianism. War broke out, and the Frankish king Clovis defeated the Visigothic king Alaric II in 507. The Franks then conquered Aquitania and captured Toulouse in 508. The Visigoths moved their capital to Toledo in Spain. Toulouse became a smaller city in the Frankish kingdom.

Frankish Rule: From 508 to 768

After the Frankish conquest, Toulouse went through a tough time. There was bad weather, plagues, and a decline in education. After Clovis died in 511, his kingdom was divided among his sons. Aquitaine was loosely controlled by Frankish kings, who appointed dukes to rule for them. In 680, the Duchy of Vasconia and Aquitaine joined together under Duke Felix. The Frankish kings were weak, and independent dukes started to rule Aquitaine from Toulouse.

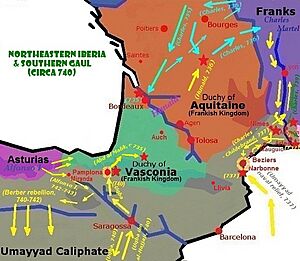

In the early 8th century, Arabs from Spain arrived. They captured Narbonne in 719. Al-Samh, the governor of Muslim Spain, gathered a large army to conquer Aquitaine. He besieged Toulouse. After three months, just as the city was about to give up, Duke Odo of Aquitaine returned with an army. He defeated the Arabs in the Battle of Toulouse in 721. This was a huge defeat for the Arabs and stopped their expansion westward.

Around 730, Duke Odo made an alliance with a Muslim ruler in Catalonia. This helped him focus on the Frankish threat from the north. But in 731, the Muslim ruler rebelled, and the new governor of Spain, Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi, attacked Aquitaine. He defeated Odo's army in Bordeaux and moved north. Odo asked the Frankish leader Charles Martel for help. In 732, at the Battle of Poitiers, Charles Martel defeated the Arabs.

After this battle, Odo had to accept Frankish authority. He died in 735. His son, Duke Hunald I of Aquitaine, rebelled against the Franks. Charles Martel sent troops and captured Bordeaux. Hunald was forced to accept Frankish rule. Later, Charles Martel's son, Pippin the Short, became king of the Franks. He spent eight years conquering Aquitaine, Toulouse, and Gascony. In 768, the last resistance ended.

Carolingian Franks: From 768 to 877

Toulouse, Aquitaine, and Gascony were now fully part of the Frankish kingdom. After Pippin the Short died in 768, his son Charlemagne became the sole ruler. In 778, Charlemagne led his army into Spain. On his way back, his army was attacked by Basque warriors. Realizing that the local people were not fully loyal, Charlemagne reorganized the region. He appointed Frankish counts (officials) to rule cities like Toulouse.

In 781, Charlemagne created the Kingdom of Aquitaine. He gave the crown to his three-year-old son, Louis. This was done to ensure the loyalty of the local people. Toulouse became a major military base against Muslim Spain. Military campaigns were launched from the city almost every year. In 801, Barcelona and much of Catalonia were conquered, forming the southern border of the Frankish empire.

In 814, Charlemagne died. His son Louis became Emperor. The Kingdom of Aquitaine was given to Louis's second son, Pippin. But Louis had another son, Charles the Bald, and his mother wanted him to inherit land too. This caused fights among Louis's sons, which weakened the Frankish empire.

In 838, Pippin I of Aquitaine died. Louis the Pious made Charles the Bald king of Aquitaine. After Louis the Pious died in 840, a war broke out among his sons. In 843, they signed the Treaty of Verdun, dividing the empire into three parts. Charles the Bald received the western part, which would become France.

These family fights made the empire weak, and the Vikings took advantage. In 844, the Vikings sailed up the Garonne River, captured Bordeaux, and plundered the area around Toulouse. They did not attack Toulouse itself.

In 845, Charles the Bald made a treaty with Pippin II of Aquitaine. But the people of Aquitaine soon became unhappy with Pippin. In 849, Charles received Toulouse from its count, Frédelon. Charles then confirmed Frédelon as the count of Toulouse. This started the dynasty of the counts of Toulouse.

In 855, Charles the Bald recreated the kingdom of Aquitaine and gave the crown to his son, Charles the Child. Pippin II escaped from a monastery and tried to start a rebellion. He even asked the Vikings for help. In 864, he led a Viking army to besiege Toulouse, but they failed.

By 866, the central government in France was losing power. Local counts became very powerful and started their own family dynasties. Wars between counts and the central government weakened defenses against the Vikings. Western Europe entered a new difficult period.

In 877, Charles the Bald signed a document that allowed counts to pass their titles to their sons. This helped create the feudal system in Europe. Charles died soon after. His son, Louis the Stammerer, became king of France. He did not choose a new king for Aquitaine, ending that kingdom. By the late 9th century, the counts in southern France, including Toulouse, became very independent.

Rise of the County of Toulouse: From 877 to 10th Century

By the end of the 9th century, Toulouse was the capital of the County of Toulouse. It was ruled by an independent family founded by Frédelon. The counts of Toulouse faced challenges from other powerful counts. But they survived and even gained more land. In 918, the county acquired Gothia, which doubled its size. This reunited Toulouse with the Mediterranean coast. The County of Toulouse became a large region, which would later be known as the province of Languedoc. Toulouse would never again be part of Aquitaine, whose capital moved to other cities.

The French king's power became very weak. Local rulers, like the counts of Toulouse, became almost like kings in their own areas. By the end of the 10th century, France was ruled by thousands of local lords. The counts of Toulouse gradually lost direct control over many areas. By 1000, they only ruled a few scattered lands. The city of Toulouse itself was ruled by a viscount, who was independent of the counts.

During this time, invasions continued. In the 920s, an army from Muslim Spain crossed the Pyrenees and reached Toulouse, but did not capture it. Four years later, the Magyars also reached Toulouse before being defeated. The wars and invasions left the county in disarray. Many farms were abandoned. However, Toulouse's closeness to Muslim Spain meant it received new knowledge and culture from places like Córdoba. It kept more of its Roman heritage than northern France.

Toulouse in the 11th Century

At the start of the new millennium, the church in Toulouse needed reforms. Important churches like Saint-Sernin, the Daurade basilica, and the Saint-Étienne cathedral were not well-maintained. Bishop Isarn, with help from Pope Gregory VII, gave the Daurade Basilica to the Cluniac abbots in 1077. At Saint-Sernin, a provost named Raimond Gayrard wanted to build a new basilica. He got permission from Pope Urban II to dedicate the basilica in 1096.

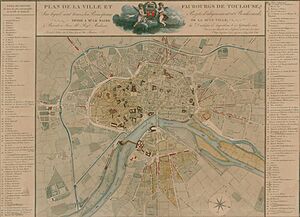

During this period, Toulouse developed better farming methods. New neighborhoods like Saint-Michel and Saint-Cyprien were built. The Daurade bridge, connecting Saint-Cyprien to the city, was built in 1181.

Toulouse in the 12th Century

The end of the 11th century saw Count Raymond IV leave for the Crusades. This led to wars over who would rule Toulouse. The city was besieged several times. In 1119, the people of Toulouse declared Alphonse Jourdain their count. In return, Jourdain lowered their taxes.

When Jourdain died, a new government of eight "capitulaires" was created. These officials, later called capitouls, managed trade and enforced laws. The first official acts of the city's consuls date back to 1152.

By 1176, the city council had 12 members, each representing a district. The consuls often disagreed with Count Raimond V. The city was divided, but after 10 years of fighting, the count gave in to the town council in 1189.

Construction of the Capitole de Toulouse began in 1190. The capitouls, now with 24 members, gained rights to law enforcement, trade, and taxation. The capitouls gave Toulouse a lot of independence for almost 600 years, until the French Revolution.

Toulouse in the 13th Century

Catharism was a Christian movement that believed in separating the material and spiritual worlds. It was popular in southern France. The Cathars were accused of heresy. Simon de Montfort tried to eliminate them.

Bishop Foulques fought against the Cathar heresy. He supported the Albigensian Crusade and rebuilt the Toulouse Cathedral. This new style of church architecture was designed to preach and restore the image of the Catholic Church. The city's consuls, however, did not want to divide the city. They refused to identify the "heretics." Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, a Catholic who had been excommunicated, felt sympathy for the Cathars after a violent event at Béziers.

Simon de Montfort's first siege of Toulouse in 1211 failed. But two years later, he defeated the city's army. He entered the city in 1216 and declared himself count. De Montfort was killed during the Siege of Toulouse in 1218. In 1219, Raymond VI, seeing the support from the people, gave his remaining powers to the Capitouls.

Toulouse in the 13th to 14th Centuries

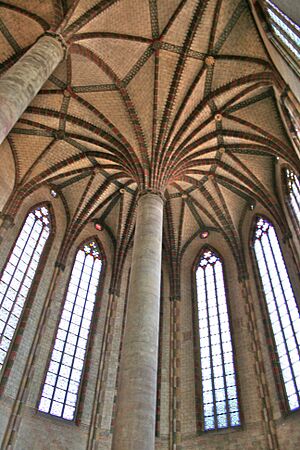

The fight against Catharism had big effects on Toulouse. In 1215, Saint Dominic founded the Order of Preachers there. The 1229 Treaty of Paris created the University of Toulouse. Its main goal was to teach theology and philosophy to fight heresy. This also started a nearly four-century period of inquisition, where suspected people faced harsh penalties or were forced to convert.

Count Raimond VII died in 1249 without an heir. The county then passed to the King of France, and the Capitouls' power weakened. In 1321, the Jews of Toulouse faced a violent event during the Shepherds' Crusade. Homes were ransacked, and those who refused to be baptized were killed. In 1323, the Consistori del Gay Saber was founded in Toulouse to preserve the lyric art of the troubadours. Toulouse became a center for Occitan literature for the next hundred years.

The city grew richer through trade in Bordeaux wine, grains, and textiles with England. But Toulouse also suffered from the inquisition, plague, fires, floods, and the Hundred Years' War. The city's population dropped significantly, even with new people moving in.

In 1368, Pope Urban V ordered that the remains of the famous philosopher Thomas Aquinas be moved to the Church of the Jacobins in Toulouse. This church was considered the main church of the Dominican Order.

Toulouse in the 15th to 16th Centuries

The 15th century began with King Charles VII creating the Parlement of Toulouse. This made Toulouse the main judicial center for much of southern France until the French Revolution. The king offered tax exemptions, increasing his influence and challenging the Capitouls.

There were many food shortages during this time. Roads were not safe, and Toulouse had a major fire in 1463. Many buildings were destroyed. The city's population grew, leading to a housing shortage.

Starting in 1463, trade in blue dye (woad) boomed. This dye, called "pastel," brought great wealth to Toulouse. The city used its new money to build beautiful homes and public buildings that are still seen today.

But in 1562, the French Wars of Religion began, disrupting trade. Also, woad was replaced by indigo from India, which made a darker blue.

In the mid-16th century, the University of Toulouse had nearly 10,000 students. It was a center for new ideas, even as the inquisition continued to punish people severely. During the 1562 Riots of Toulouse, battles between Huguenots (Protestants) and Catholics led to over 3,000 deaths and many homes being burned.

Toulouse in the 17th Century

When Henry IV became king, the disorder in Toulouse ended. The parlement recognized the king, and the Edict of Nantes (which granted rights to Protestants) was accepted in 1600. The Capitouls lost their remaining power. A more serious threat than political unrest reached Toulouse in 1629 and 1652: the plague.

For the first time, the city and the local parlement worked together to help those affected. Most of the wealthy people and clergy left the city. But doctors were required to stay. The remaining Capitouls prevented butchers and bakers from leaving to ensure food supply.

La Grave Hospital took in plague patients and quarantined them. Other places also cared for many patients in difficult conditions. Before closing its gates, the city attracted poor people because it offered more medical help than the countryside.

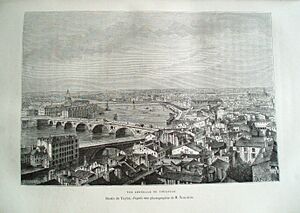

In 1654, when the second plague ended, the city was devastated. However, during the times without plague, two major projects were finished: the Pont-Neuf bridge in 1632 and the Canal du Midi in 1682. A famine also occurred in 1693.

Toulouse in the 18th Century

Louis de Mondran, inspired by his time in Paris, became the new city planner. Important projects during this period included the Grand Rond park, the Cours Dillon, and the beautiful facade of the Capitole.

In 1770, the first stone was laid for the channel named after Cardinal de Brienne. This channel connected the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean, linking the Canal du Midi to the Canal Lateral à la Garonne. It was finished six years later. Their meeting point is known as Ponts-Jumeaux.

Wealth differences grew, but there was work for local architects and sculptors. The Reynerie was the summer home of the husband of the Comtesse du Barry.

At the end of the century, the Blue Penitents worshipped at the Saint-Jérome church. The local parlement condemned Protestants, using its power in cases like the trial and execution of Jean Calas. Toulouse's population supported the parlement when it felt threatened by the monarchy. The eight Capitouls were now chosen by the parlement.

Toulouse in the 19th Century

The French Revolution completely changed Toulouse's role and its political and social structure. The city saw looting as the Parisian movement spread. Five months later, when the old system was abolished, the parlement and the Capitouls had little public support.

Toulouse's regional influence was reduced to just the department of Haute-Garonne. Clergy were required to follow new rules set by the National Assembly. A new archbishop was named, despite objections. The Capitouls were abolished on December 14, 1789. Joseph de Rigaud became Toulouse's first mayor on February 28, 1790.

In 1793, during the Paris Commune, Toulouse refused to join federalists in Paris. The possibility of war against Austria and internal resistance led to the Reign of Terror. In 1799, the fortified city resisted an attack by British and Spanish royalist armies in the first battle of Toulouse. Napoleon visited the city in 1808.

In 1814, during the Battle of Toulouse, the British army entered the city. The French imperial army had left it. This was the last battle of Napoleon's Empire, as he had given up his power eight days earlier. The French commander had not been told. Wellington's army was welcomed by royalists, preparing Toulouse for the return of King Louis XVIII.

Toulouse in the 21st Century

The AZF chemical plant in Toulouse had a large explosion on September 21, 2001. The explosion destroyed the plant, which was about 8 kilometers (5 miles) from the city center. It also damaged many homes (over 20,000 apartments), schools, churches, monuments, and shops. Twenty-nine people died, and thousands were injured. The explosion started in a building that contained ammonium nitrate.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Toulouse para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Toulouse para niños

- Counts of Toulouse

- Timeline of Toulouse

- Handwritten Annals of the City of Toulouse

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |