History of the Church of England facts for kids

The story of the Church of England officially begins with Saint Augustine of Canterbury's journey to England in AD 597. His mission helped bring Christianity to England under the Pope's authority. However, in 1534, King Henry VIII declared himself the head of the Church of England. This caused a big split with the Pope. Because of this split, some people believe the Church of England only truly started in the 1500s.

Christianity first arrived in the British Isles around AD 47, during the time of the Roman Empire. Bishops from Britain even attended important church meetings in the 300s. Christianity grew in Sub-Roman Britain, and later in Ireland, Scotland, and Pictland. But then, the Anglo-Saxons, who were pagans, took over much of Britain. Missionaries from Augustine's group and from Scotland helped bring Christianity back to the Anglo-Saxons. The church in Wales stayed separate for a long time.

The Church of England became the official church through an Act of Parliament called the Act of Supremacy. This started a period known as the English Reformation. When Queen Mary I and King Philip ruled, the church rejoined Rome in 1555. But when Queen Elizabeth I became queen, she again rejected the Pope's power. This led to the Elizabethan Religious Settlement in 1558. This settlement decided that the church would be both Catholic (meaning universal) and Reformed (meaning it had changed some things).

Contents

Early Christianity in Britain

Some old stories say Christianity came to Britain in the 1st or 2nd century. But these stories are probably not true. The first real proof of Christians among the native Britons comes from the early 200s. The first Christian groups likely formed a few decades before that.

We know that three bishops from Roman Britain attended a church meeting in Arles in 314. Other bishops went to meetings in Sardica in 347 and Ariminum in 360. Many writings from the 300s also mention the church in Roman Britain. Britain was also home to Pelagius, a monk who disagreed with Augustine of Hippo about original sin. The first known Christian martyr in Britain, St Alban, probably lived in the early 300s. Many churches are named after him.

Irish Anglicans believe their church started with St Patrick, who was a Roman Briton. He lived before Anglo-Saxon Christianity. Anglicans also see Celtic Christianity as an early form of their church. This is because Irish and Scottish missionaries, like St Patrick and St Columba, helped bring Christianity back to parts of Britain in the 500s.

Augustine and the Anglo-Saxon Period

Anglicans often say their church began when St Augustine arrived in the Kingdom of Kent in the late 500s. He led a mission from Pope Gregory I to the pagan Anglo-Saxons. But Christianity had been in the British Isles even before that.

Æthelberht of Kent's queen, Bertha, was a Christian. She had a chaplain with her and had restored an old Roman church. This church, Saint Martin's, is the oldest church in England still used today. Æthelberht, though pagan, let his wife worship freely. He later asked Pope Gregory I to send missionaries. In 596, the Pope sent Augustine and a group of monks.

Augustine and his followers landed on the Island of Thanet in 597. Æthelberht allowed them to settle and preach in Canterbury. By the end of that year, the king himself became a Christian. Augustine was made a bishop. At Christmas, 10,000 of the king's people were baptized.

Augustine sent a report to Pope Gregory. In 601, others brought the Pope's replies and gifts. Gregory wanted Augustine to appoint twelve bishops and send one to York. Augustine did not fully follow this plan. He did make Mellitus bishop of London and Justus bishop of Rochester.

Pope Gregory also gave advice on pagan temples. He wanted them to be used for Christian services. He asked Augustine to change pagan practices into Christian ceremonies. He said, "he who would climb to a lofty height must go up by steps, not leaps."

Augustine rebuilt an old church in Canterbury as his cathedral. He also founded a monastery. He died before finishing the monastery. He is buried in the Church of St Peter and St Paul.

In 616, King Æthelberht died. Kent and other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms went back to paganism for a few decades. Over the next 50 years, Celtic missionaries from Northumbria and Lindisfarne helped spread Christianity again. Mercia and Sussex were some of the last kingdoms to become Christian.

The Synod of Whitby in 664 was a very important meeting. King Oswiu of Northumbria decided to follow Roman Christian practices instead of Celtic ones. This meeting set the Roman date for Easter and the Roman style of monastic haircuts in Britain. King Oswiu led the meeting and made the final decision.

Later, Theodore of Tarsus, an archbishop of Canterbury, helped organize the church in England even more.

Medieval Church Growth

In medieval Europe, there was often tension between kings and the Pope. They disagreed about laws for church leaders, church wealth, and who could appoint bishops. This happened a lot during the reigns of Henry II and John. England became a united country earlier than others in Europe. This meant that church and government areas were quite large. England was divided into two main church areas: the Province of Canterbury and the Province of York, each led by an archbishop.

After the Viking attacks in the 800s, many English monasteries stopped working. Cathedrals were often run by small groups of married priests. King Edgar and Archbishop Dunstan started a big reform in 970. They decided that bishops should set up monasteries in their cathedrals, following the Benedictine rule.

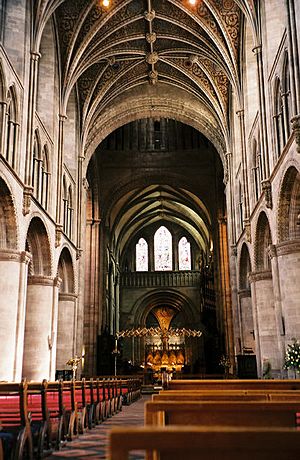

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, William the Conqueror and Archbishop Lanfranc continued these reforms. Some cathedrals became Benedictine monasteries. However, many bishops preferred secular cathedrals (not run by monks) because it was easier to manage their money. Bishops of monastic cathedrals often had legal problems with the monks. They also started living elsewhere, like in London or York.

An important part of medieval Christianity was honoring saints. People would go on pilgrimages to places where a saint's relics (remains) were kept. Having a popular saint's relics brought money to the church. People would donate hoping for spiritual help or healing. Famous churches that benefited included St. Alban's Abbey, Durham, Ely, Westminster Abbey, and Chichester. But the most famous was Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury. He was killed by King Henry II's men in 1170. Canterbury became a very popular pilgrimage site, second only to Santiago de Compostela in the 1200s.

Breaking Away from the Pope

John Wycliffe (around 1320 – 1384) was an English theologian. He was an early critic of the Roman Catholic Church in the 1300s. He started the Lollard movement, which disagreed with many church practices. He also opposed the Pope's power over kings. Wycliffe said that the Church in Rome was not the head of all churches. He also believed that the Bible alone was enough for Christians to live by. The Lollard movement continued to spread his ideas, even when they were persecuted.

The first break with Rome happened when Pope Clement VII refused to cancel King Henry VIII's marriage to Catherine of Aragon. The Pope was afraid of Catherine's nephew, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Henry first asked for an annulment in 1527. He then put pressure on Rome. In 1529, he argued that the king should have spiritual power, not the Pope. In 1531, Henry demanded money from the clergy (church leaders). He also demanded they recognize him as their supreme head. The church in England agreed on February 11, 1531. But Henry still tried to make a deal with the Pope, which failed.

In May 1532, the Church of England agreed to give up its law-making power to the king. In 1533, the Statute in Restraint of Appeals stopped English people from appealing to Rome on marriage or church money matters. This gave power to the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. This allowed Thomas Cranmer, the new Archbishop of Canterbury, to annul Henry's marriage. Henry then married Anne Boleyn. Pope Clement VII excommunicated Henry VIII in 1533.

In 1534, the Act of Submission of the Clergy removed all appeals to Rome. This ended the Pope's influence. The first Act of Supremacy in 1536 confirmed Henry as the Supreme Head of the Church of England. (Later, this title changed to "Supreme Governor of the Church of England," which the monarch still holds today.)

These changes allowed Henry to annul his marriage and gain control of the church's great wealth. Thomas Cromwell led an investigation into church property in 1535. This led to the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536–1540). Huge amounts of church land and property went to the Crown and then to English nobles. This removed the main supporters of the Pope and gave people a reason to support a separate English church under the king.

The Reformation Begins

Many Roman Catholics believe the Church of England truly began in 1534 when it split from Rome. Anglicans, however, believe their church continued from the time of St. Augustine in 597. They see Henry VIII's rejection of papal authority as making the Church of England a separate church, but still connected to its past. The Church of England had its own organization by 672-673. Henry's laws declared the English crown as the "only Supreme Head in earth of the Church of England."

The Thirty-Nine Articles and the Acts of Uniformity led to the Elizabethan Religious Settlement. By the late 1600s, the English church called itself both Catholic and Reformed. The English monarch was its Supreme Governor.

King Henry VIII's Role

The English Reformation started because Henry VIII wanted a male heir. He found it useful to replace the Pope's authority with his own power. Early laws focused on who had supreme power. The Institution of the Christian Man (1537) was written by bishops to teach people church doctrine. The Great Bible in 1538 brought an English Bible into churches. The Dissolution of the Monasteries by 1540 gave the Crown vast church lands. This removed centers of loyalty to the Pope and gave nobles a reason to support the new church.

Cranmer, Parker, and Hooker

By 1549, the church reform gained speed with the first English prayer book, the Book of Common Prayer. This book made English the language of public worship. Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote much of the first prayer book. Others like Matthew Parker and Richard Hooker continued to shape Anglican beliefs. Cranmer knew about the ideas of other Reformers in Europe.

During the short rule of Edward VI, Henry's son, Cranmer moved the Church of England more towards Protestant ideas. This was seen in the second prayer book (1552) and the Forty-Two Articles. But this reform was quickly undone when Queen Mary, a Roman Catholic, became queen in 1553. She brought the church back under Rome.

In the 1500s, religion was very important for society and political power. Religious differences could cause unrest and even war. When Queen Elizabeth came to the throne in 1558, she tried to find a solution. The Elizabethan Religious Settlement tried to satisfy both Catholic and Protestant groups within one national church. This was done through the 1559 Book of Common Prayer, the Thirty-Nine Articles, and other works. These became the basis of Anglican beliefs.

The new prayer book was similar to Cranmer's earlier versions. The Thirty-Nine Articles were based on Cranmer's Forty-Two Articles. Most people accepted Elizabeth's religious settlement, though some were more enthusiastic than others. It was made law, but Catholic bishops in Parliament voted against it. Protestants who wanted more reform, called Puritans, also opposed it. Both groups faced punishments.

Even after separating from Rome, the Church of England under Henry VIII remained mostly Catholic. Pope Leo X had even called Henry "defender of the faith" for attacking Lutheranism. Some Protestant changes under Henry included removing some religious images, ending pilgrimages, and closing shrines. But Henry kept the Six Articles of 1539, which confirmed the church's Catholic nature.

All this happened during a time of big religious change in Europe, known as the Protestant Reformation. Once the split happened, some reform was probably unavoidable.

Only under Henry's son, Edward VI (ruled 1547–1553), did major changes happen in local churches. The church liturgy was translated and revised to be more Protestant. The Book of Common Prayer, published in 1549 and revised in 1552, became official.

Reunion with Rome

After Edward died, his half-sister, the Roman Catholic Mary I (ruled 1553–1558), became queen. She reversed Henry's and Edward's changes. She first undid her brother's reforms, then brought the church back together with Rome. The Marian Persecutions of Protestants happened during her rule. Many people were executed for their faith. This led to her being called "Bloody Mary." This view was spread by Foxe's Book of Martyrs, published during Elizabeth I's reign.

Historians estimate that 274 religious executions happened in Mary's last three years. This was more than in any Catholic country in Europe at that time.

The Second Split

The second split, which led to the current Church of England, happened later. After Mary died in 1558, her half-sister Elizabeth I (ruled 1558–1603) became queen. Elizabeth strongly opposed papal control and brought back the idea of a separate English church. In 1559, Parliament recognized Elizabeth as the Church's supreme governor. A new Act of Supremacy also removed anti-Protestant laws. A new Book of Common Prayer came out that same year. Elizabeth oversaw the "Elizabethan Religious Settlement," trying to unite Puritans and Catholics within one national church. Elizabeth was excommunicated by Pope Pius V on February 25, 1570. This finally broke the connection between Rome and the Anglican Church.

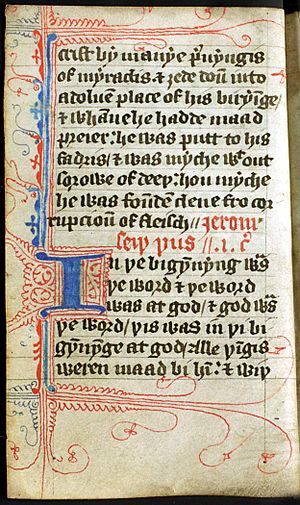

The King James Bible

Shortly after becoming king, James I wanted to unite the Church of England. He set up a group of scholars from all church views to create a new, unified Bible translation. This translation would be free of extreme Protestant or Catholic influences. The project started in 1604 and finished in 1611. It became the Authorised Version for the Church of England and other Anglican churches.

The New Testament was translated from the Textus Receptus (Received Text) Greek texts. The Old Testament was translated from the Masoretic Hebrew text. The Apocrypha was translated from the Greek Septuagint. Forty-seven scholars worked in six groups in Oxford, Cambridge, and Westminster. They worked on different parts, then compared and revised their drafts.

This translation had a huge impact on English literature. Famous writers like John Milton and William Wordsworth were inspired by it.

The Authorised Version is often called the King James Version, especially in the United States. King James himself wasn't involved in the translation. But his permission was needed, and he set rules for the process. For example, he banned footnotes and made sure Anglican views were included. A dedication to James is still found in modern editions.

English Civil War

For the next century, under James I and Charles I, there were big shifts between two groups. The Puritans wanted more changes, while conservatives wanted to stay closer to old traditions. The failure to meet Puritan demands was a cause of the English Civil War. The war led to the death of King Charles I and Archbishop William Laud. For about ten years (1647–1660), Christmas and other church feasts were even banned to remove signs of "Popishness." During the Commonwealth of England, Anglicanism was no longer the official church. The Book of Common Prayer was replaced.

Despite this, about a quarter of English clergy refused to change. The 1600s became a "Golden Age" for Anglicanism. The Caroline Divines, like Andrewes and Laud, rejected Roman claims. They also refused to adopt the ways of Continental Protestants. They believed truth was in the Bible and the bishops, following the early church. They also valued reason in theology.

Restoration and Beyond

With the Restoration of Charles II, Anglicanism was brought back. It was similar to the Elizabethan version. But the idea of everyone in England belonging to one church had to be given up. The 1662 revision of the Book of Common Prayer became the main text for the church after the civil war.

When King Charles II returned in 1660, he appointed his supporters to church positions. He wanted to bring back the power of bishops. He also wanted to include "moderate dissenters" to unite Protestants.

Glorious Revolution and Toleration

James II was overthrown in 1688 by William of Orange. The new king quickly eased religious tensions. Many of his supporters were Nonconformist Protestants. The Act of Toleration, passed on May 24, 1689, gave Nonconformists freedom of worship. This meant Protestants who disagreed with the Church of England, like Baptists and Quakers, could have their own places of worship and teachers. However, this did not apply to Catholics or Unitarians. Nonconformists still faced social and political limits, like being excluded from government jobs.

The religious settlement of 1689 shaped policy until the 1830s. The Church of England was dominant. It kept outsiders from important roles in government, business, and education. But old tensions lessened, and a new spirit of tolerance grew. Restrictions on Nonconformists were mostly ignored or slowly removed. The Toleration Act of 1689 allowed nonconformists to have their own chapels and preachers. The religious landscape of England took its current shape. The Anglican church was in the middle, and Roman Catholics and Puritans who disagreed with the official church continued outside it.

18th Century

Anglicanism Spreads Outside England

Since the 1600s, Anglicanism has spread widely. It has grown in different places and cultures. This has led to different ways of worship and beliefs.

At the same time as the English Reformation, the Church of Ireland also separated from Rome. It adopted beliefs similar to England's. But unlike in England, the Anglican church in Ireland never gained the loyalty of most people, who remained Roman Catholic. In 1582, the Scottish Episcopal Church was formed when James VI of Scotland tried to bring back bishops. The Church of Scotland had become fully Presbyterian.

The Scottish Episcopal Church helped create the Episcopal Church in the United States of America after the American Revolution. They consecrated the first American bishop, Samuel Seabury. English bishops had refused to do this because he could not swear loyalty to the English crown. The Scottish and American churches have different ways of governing themselves. They are led by a presiding bishop or primus, not a metropolitan or archbishop. The names of these churches led to the term Episcopalian for Anglicans in some parts of the world.

The four (now six) Welsh dioceses were part of the Province of Canterbury during the English Reformation. They stayed that way until 1920, when the Church in Wales became its own province. Welsh people in the 1700s and 1800s were very interested in Christianity. But in the 1500s, most Welsh people accepted the church's reformation because the English government was strong enough to make them.

Anglicanism spread outside the British Isles through people moving and through missionary work. In 1609, a shipwreck led to the settlement of Bermuda. This became official in 1612. St Peter's Church in St George's, Bermuda, is the oldest Anglican church outside Britain and Ireland. It is also the oldest non-Roman Catholic church in the New World. It was part of the Church of England until 1978. The Church of England was the official religion in Bermuda. People were required by law to attend Church of England services in the 1600s.

English missionary groups like USPG and the Church Missionary Society (CMS) were formed in the 1600s and 1700s. They aimed to bring Anglican Christianity to British colonies. By the 1800s, these missions spread to other parts of the world. These groups had different ideas about worship and beliefs. For example, the SPG was influenced by the Catholic Revival, while the CMS was influenced by Evangelicalism. So, the churches they started reflected these different ideas.

19th Century and After

1801–1914

The Plymouth Brethren left the established church in the 1820s. During this time, the church was affected by the Evangelical revival and the growth of industrial towns. Various Nonconformist churches, especially Methodism, grew. From the 1830s, the Oxford Movement became important. It led to the revival of Anglo-Catholicism. From 1801, the Church of England and the Church of Ireland were united. This lasted until the Irish church became separate in 1871.

The growth of the Evangelical and Catholic "revivals" in the 1800s greatly influenced Anglicanism. The Evangelical Revival led to important social movements. These included the abolition of slavery, child welfare laws, and the development of public health and public education. It also led to the creation of the Church Army, a group focused on evangelism and social welfare.

The Catholic Revival had a deeper impact on Anglican worship. It made the Eucharist the main act of worship. It brought back the use of special clothes (vestments), ceremonies, and acts of devotion that had been banned. It also influenced Anglican theology through figures like John Henry Newman. Many churches were rebuilt in a more medieval, Gothic style. Both revivals led to significant missionary efforts in the British Empire.

Prime Ministers and the Queen

Prime ministers continued to play a big role in church appointments. William Ewart Gladstone paid a lot of attention to church vacancies. He annoyed Queen Victoria by making appointments she disliked. He tried to match candidates' skills to church needs. He also favored Liberals who supported his politics. Disraeli, his rival, also favored Conservative bishops but tried to balance different church groups. He sometimes chose more qualified candidates over party advantage. Disraeli and Queen Victoria often disagreed on church nominations because she disliked high churchmen.

1914–1970

The modern military chaplain role comes from the First World War. A chaplain provides spiritual support to soldiers. The Army Chaplains Department was given the title "Royal" for their wartime service.

An attempt to revise the Book of Common Prayer in 1928 failed in Parliament.

During the Second World War, the head of chaplaincy in the British Army was an Anglican chaplain-general.

A movement to unite with the Methodist Church in the 1960s failed. It was rejected by the General Synod in 1972. Methodists started the idea, and Anglicans welcomed it, but they couldn't agree on all points.

1970–Present

The Church Assembly was replaced by the General Synod in 1970.

On March 12, 1994, the Church of England ordained its first female priests. On July 11, 2005, the General Synod voted to allow women to become bishops. Some people in the church opposed these changes. Adjustments were made for parishes that did not want to accept women priests.

The first black archbishop of the Church of England, John Sentamu, was made Archbishop of York on November 30, 2005. He was originally from Uganda.

In 2006, the Church of England's General Synod publicly apologized for its historical role in owning slave plantations. A charitable gift in 1710 meant that thousands of slaves on sugar plantations in Barbados and Barbuda were treated terribly and branded as property of the "society."

In 2010, for the first time, more women than men were ordained as priests in the Church of England (290 women and 273 men).

Images for kids

-

The square tower of St Peter's Church, Barton-upon-Humber (around 990) is an example of late Anglo-Saxon church architecture.

-

King Henry VIII was responsible for the Church of England's independence from the Roman Catholic Church (portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1540).

-

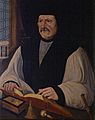

Thomas Cranmer (1489–1556), Archbishop of Canterbury and main compiler of the first two versions of the Book of Common Prayer.

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |