Mesa Verde National Park facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mesa Verde National Park |

|

|---|---|

|

IUCN Category II (National Park)

|

|

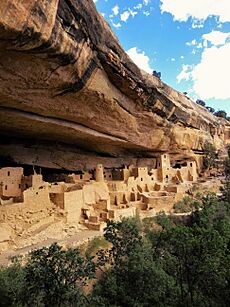

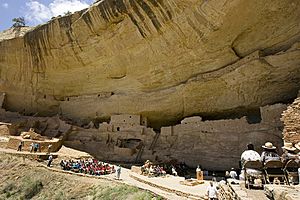

Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde

|

|

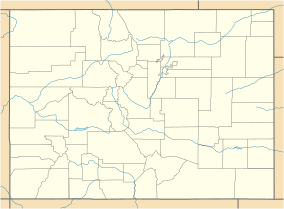

| Location | Montezuma County, Colorado, United States, North America |

| Nearest city | Cortez, Colorado |

| Area | 52,485 acres (212.40 km2) |

| Established | June 29, 1906 |

| Visitors | 563,420 (in 2018) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Mesa Verde National Park |

| Type: | Cultural |

| Criteria: | iii |

| Designated: | 1978 (2nd session) |

| Reference #: | 27 |

| Region: | Europe and North America |

| Designated: | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference #: | 66000251 |

Mesa Verde National Park is a special national park in the United States. It is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. You can find it in Montezuma County, Colorado. This park protects some of the best-preserved ancient homes of the Ancestral Pueblo people.

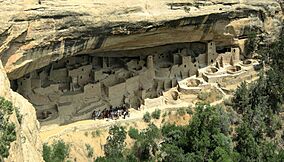

The park was created in 1906 by the U.S. Congress and President Theodore Roosevelt. It covers about 52,485 acres (212 square kilometers). This area is close to the Four Corners region of the American Southwest. Mesa Verde has over 5,000 ancient sites. This includes 600 cliff dwellings. It is the largest place in the U.S. that protects archaeological sites. Mesa Verde means "green table" in Spanish. It is famous for amazing structures like Cliff Palace. This is one of the biggest cliff dwellings in North America.

Around 7500 BC, nomadic groups called the Foothills Mountain Complex lived here seasonally. Later, Archaic people built simple shelters. By 1000 BC, the Basketmaker culture appeared. Then, around 750 AD, the Ancestral Puebloans developed from them.

The Pueblo people hunted, gathered, and farmed. They grew corn, beans, and squash, known as the "Three Sisters". They built the first pueblos after 650 AD. By the late 1100s, they started building the huge cliff dwellings. These are what the park is most famous for. Around 1285, after a time of hardship and long droughts, they moved south. They went to places in Arizona and New Mexico.

Contents

- Who Lived at Mesa Verde?

- Early People: Paleo-Indians

- Archaic Period: Settling Down

- Basketmaker Culture: Farmers and Weavers

- Ancestral Puebloans: Building Cliff Dwellings

- Pueblo I Period: 750 to 900 AD

- Pueblo II Period: 900 to 1150 AD

- Pueblo III Period: 1150 to 1300 AD

- Conflict and Change

- Leaving Mesa Verde: The Great Migration

- How Communities Were Organized

- Amazing Architecture

- Star Gazing: Astronomy

- Farming and Water Systems

- Hunting and Gathering Food

- Pottery: Art and Tools

- Rock Art and Murals

- Mesa Verde's Climate

- Nature and Landscape

- How Mesa Verde Was Formed

- Rediscovering Mesa Verde

- Mesa Verde Becomes a National Park

- Key Sites to See

- Images for kids

- See also

Who Lived at Mesa Verde?

Early People: Paleo-Indians

The first people in the Mesa Verde region were nomadic Paleo-Indians. They arrived around 9500 BC. They followed large animals and camped near rivers. The climate became warmer and drier after 9600 BC. Pine forests grew, bringing new animals. More Paleo-Indians started living on the mesa around 7500 BC. They used a tool called an atlatl to hunt smaller animals. This was important as larger animals disappeared.

Archaic Period: Settling Down

The Archaic period in North America began around 6000 BC. Archaeologists believe these people grew from local Paleo-Indians. But they also learned from groups in other areas. These early Archaic people used the atlatl. They gathered more types of plants and hunted more animals. They still moved around a lot. They lived in rock shelters and made rock art.

By the late Archaic period, more people lived in semi-permanent rock shelters. These shelters kept things like baskets and sandals safe. They also started making small twig figures of animals. Trade became more common. They traded for things like obsidian and turquoise. People also started building simple houses from mud and wood. Their early farming efforts led to the end of the Archaic period around 1000 BC.

Basketmaker Culture: Farmers and Weavers

Around 1000 BC, corn came to the Mesa Verde area. People started to settle down in pithouse villages. This led to the Basketmaker culture. The Basketmaker II people were good at both gathering food and farming. They still used the atlatl. They made beautiful woven baskets, but no pottery yet. By 300 AD, corn was their main food. They relied less on wild foods.

Basketmaker II people made many household items. These included sandals, robes, and blankets. They also made clay pipes. Their skeletons show they worked hard and traveled a lot. They buried their dead near their homes. They often included special items as gifts. This might show that some people had higher social status. Their unique rock art can be found all over Mesa Verde. They often drew animals and people. A common figure was the hunchbacked flute player, called Kokopelli by the Hopi.

By 500 AD, people started using bows and arrows instead of atlatls. Pottery began to replace baskets. This marked the start of the Basketmaker III Era. Clay pots were much better for storing water and cooking. They also protected seeds from mold and insects. By 600 AD, people were cooking soups in clay pots. Year-round villages started to appear. The population grew a lot in the early 600s. By 675 AD, about 1,000 to 1,500 people lived in Mesa Verde.

Beans and new types of corn arrived around 700 AD. By 775 AD, some villages had over a hundred people. They started building large storage buildings above ground. Basketmakers tried to store enough food for a year. But they could still move if food became scarce. By the late 700s, small villages were replaced by larger ones. These larger villages were lived in for many years. Basketmaker III people also started holding big ceremonies. These often happened near community pit structures.

Ancestral Puebloans: Building Cliff Dwellings

Pueblo I Period: 750 to 900 AD

The Pueblo I period began around 750 AD. This time brought big changes in how buildings were designed. People built connected, year-round homes called pueblos. Many daily activities moved from underground pit-houses to these new homes. Pit-houses then became mostly for community ceremonies. But large families still used them, especially in winter. By the late 700s, Pueblo people built square pit structures. Archaeologists call these protokivas. They were usually 3 to 4 feet (0.9 to 1.2 meters) deep. They were also 12 to 20 feet (3.7 to 6.1 meters) wide.

The first pueblos appeared after 650 AD. By 850 AD, over half of Pueblo people lived in them. As more people lived together, hunting and gathering became harder. They relied more on farmed corn. This change to a settled life changed Pueblo society forever. Villages grew from 1-3 families to 15-20 families. Populations reached about two hundred people. This brought more safety and cooperation. It also helped trade and marriage between groups. By the late 700s, four different cultural groups lived in the same villages.

Large Pueblo I settlements used resources from 15 to 30 square miles (39 to 78 square kilometers). They were often grouped in threes, about 1 mile (1.6 km) apart. By 860 AD, about 8,000 people lived in Mesa Verde. In larger villages, people dug huge pit structures. These were 800 square feet (74 square meters) and became central gathering places. These structures were early forms of the Pueblo II Era great houses of Chaco Canyon.

Even with growth, rainfall was unpredictable. This led to many villages being left after less than 40 years. By 880 AD, Mesa Verde's population started to shrink. By the early 900s, many people left the region. They moved south to Chaco Canyon. They hoped to find more reliable rain for farming. As people moved south, Chaco Canyon became more important. By 950 AD, Chaco was the main cultural center.

Pueblo II Period: 900 to 1150 AD

The Pueblo II Period saw the growth of communities around the great houses of Chaco Canyon. Pueblo people kept their own culture. But they also blended new ideas with old traditions. This led to new building styles. Droughts in the late 800s made dry farming difficult. So, for 150 years, people only farmed near water sources. By the early 1000s, crop yields improved. By 1050 AD, the population grew again. More people moved to Mesa Verde from the south.

Pueblo farmers used masonry reservoirs more often. In the 1000s, they built check dams and terraces. These helped save soil and water runoff. These smaller fields helped prevent crop failures. By the mid-900s and early 1000s, protokivas became smaller, round structures called kivas. These were usually 12 to 15 feet (3.7 to 4.6 meters) across. Mesa Verde kivas included a sipapu. This is a hole that symbolized where the Ancestral Puebloans came from. At this time, people started building with stone. Before, they used post and mud buildings. Stone building became common in the 1000s and 1100s.

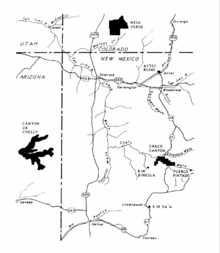

Chacoan influence spread to Mesa Verde. This was seen in the Chaco-style masonry great houses. These became important centers in many Pueblo villages after 1075 AD. Far View House is the largest of these. It was likely built between 1075 and 1125 AD. During the early 1100s, control shifted from Chaco to Aztec, New Mexico. By 1150 AD, another drought hit. This stopped great house building at Mesa Verde for a while.

Pueblo III Period: 1150 to 1300 AD

A severe drought from 1130 to 1180 AD caused many people to leave Chaco Canyon. More people moved to Mesa Verde. This caused a big population increase. Settlements grew to 600 to 800 people. This meant people moved less often. They had to farm more to feed everyone. More tree cutting also happened. This reduced places for wild plants and animals. So, people relied even more on farmed crops. These crops were easily affected by drought.

The Chacoan system brought many goods to Mesa Verde. These included pottery, shells, and turquoise. But by the late 1100s, this system fell apart. Fewer goods came to Mesa Verde. The area became more isolated. For about 600 years, most farmers lived in small homes on mesa tops. These were near their fields and water. This continued into the late 1100s. But by the early 1200s, people started living in canyons. These places were close to water and fields.

Ancestral Pueblo villages thrived in the mid-Pueblo III Era. Architects built huge, multi-story buildings. Artists made pottery with complex designs. Buildings from this time are amazing archaeological treasures. Pueblo III stone buildings lasted about 50 years. Some were used for 200 years or more. New features like towers and multi-walled buildings appeared. Mesa Verde's population stayed steady during the 1100s drought. By the early 1200s, about 22,000 people lived there. The population grew even more from 1225 to 1260 AD. Most people lived west of the mesa. Others built large multi-family homes in canyons. By 1260 AD, most Puebloans lived in big pueblos. These housed many families and over a hundred people.

The 1200s had 69 years of less rainfall in Mesa Verde. After 1270, it also got very cold. The last tree cut for building was in 1281. Fewer ceramic goods were brought in. But local pottery making stayed steady. Despite hard times, people farmed until a very dry period from 1276 to 1299. This "Great Drought" ended 700 years of people living in Mesa Verde. The last people left around 1285 AD.

Conflict and Change

During the Pueblo III period (1150 to 1300 AD), Puebloans built many stone towers. These were likely for defense. They often had hidden tunnels connecting them to kivas. People used hunting tools for conflict, like bows, arrows, and stone axes. They also made shields from hide and baskets. There was conflict on the mesa throughout the 1200s. Leaders might have gained power by sharing food during droughts. This system likely broke down during the "Great Drought." This led to more conflict between different groups.

Evidence of violence has been found in central Mesa Verde. Most of this violence happened between 1275 and 1285 AD. It is thought to be mostly conflicts among Puebloans. But evidence at Sand Canyon Pueblo suggests conflicts with people from outside the region too. These attacks happened around 1280 AD. They effectively ended centuries of Puebloan life at those sites. Many victims had skull fractures. This suggests they were hit with small stone axes. Records show that conflict was widespread in North America in the late 1200s. This was likely made worse by climate changes affecting food.

Leaving Mesa Verde: The Great Migration

The early 1200s brought cold and dry weather to Mesa Verde. This might have caused people to move there from other places. The extra people put a strain on the environment. This made farming harder during the drought. The usual rain and snow patterns failed after 1250 AD. After 1260 AD, Mesa Verde quickly lost its population. Many people moved away or died from hunger. Other small communities in the Four Corners region were also left empty.

The Ancestral Puebloans had moved before when times were hard. But the move from Mesa Verde in the late 1200s was different. The area became almost completely empty. No descendants returned to build permanent homes. Drought, lack of resources, and too many people all caused problems. But relying too much on corn was seen as a "fatal flaw" in their way of life.

The people who left Mesa Verde left few direct clues about their journey. But they left behind household items. This made archaeologists think the move was sudden. About 20,000 people lived there in the 1200s. But by the early 1300s, the area was almost empty. Many survivors may have moved to southern Arizona and New Mexico. Areas like Rio Chama and Pajarito Plateau saw more people. This matches the time of migration from Mesa Verde. Archaeologists believe the Puebloans who settled near the Rio Grande were welcomed. They were likely related to the families they joined. This migration is seen as a continuation of their society, not an end. Many others moved to the Little Colorado River. This was in western New Mexico and eastern Arizona.

While "push" factors like drought made them leave, "pull" factors also drew them away. Warmer weather, better farming, more timber, and bison herds were attractive. Today, descendants of the Puebloans live in pueblos. These include Acoma, Zuni, Jemez, and Laguna.

How Communities Were Organized

Chaco Canyon might have had some control over Mesa Verde in the late 1000s and early 1100s. But most archaeologists see Mesa Verde as many smaller communities. These were based around central sites. They were not fully part of one big government. Several ancient roads have been found. They are 15 to 45 feet (4.6 to 13.7 meters) wide. They were lined with earthen berms. Most roads connected communities and special places. Others went around great house sites. It's not clear how big the road network was. No roads have been found leading to the Chacoan Great North Road. Also, none directly connect Mesa Verde and Chacoan sites.

Special shrines, called herraduras, have been found near roads. Their purpose is not fully known. But some C-shaped herraduras have been dug up. They are thought to have been "directional shrines." They might have shown the way to great houses.

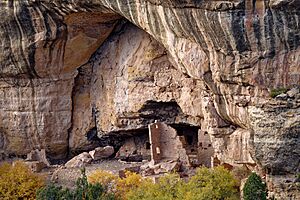

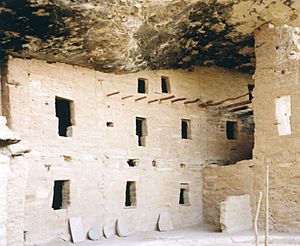

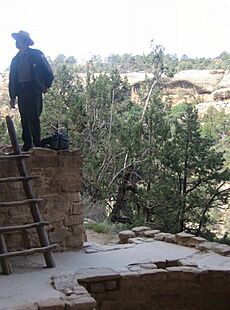

Amazing Architecture

Mesa Verde is famous for its many well-preserved cliff dwellings. These are houses built in natural rock overhangs along canyon walls. The buildings were made mostly of hard sandstone. They were held together with adobe mortar. Each building was unique because of the shape of its alcove. Unlike earlier villages on top of the mesas, cliff dwellings were very crowded. This showed a trend of people gathering into close, easy-to-defend places in the 1200s.

Pueblo buildings were made of stone. They had windows facing south. They were built in U, E, and L shapes. Buildings were closer together. This showed a deeper focus on religious ceremonies. Towers were built near kivas. They were likely used as lookouts. Pottery became more varied. It included pitchers, ladles, bowls, and jars. White pottery with black designs appeared. The colors came from plants. People also developed ways to manage water. They used reservoirs and dams to save soil and water.

The stone buildings, both on the surface and in cliffs, had T-shaped windows and doors. Some archaeologists think this shows the continued influence of the Chacoan system. Others believe these features were just part of a general Puebloan style. Or they had a spiritual meaning.

The cliff dwellings were very crowded. Mug House, a typical cliff dwelling, housed about 100 people. They shared 94 small rooms and eight kivas. The rooms were built right next to each other. Builders used every possible space.

Star Gazing: Astronomy

The Pueblo people watched the stars to plan their farming and ceremonies. They used natural land features and special buildings. Several great houses were built facing the cardinal directions (north, south, east, west). Windows, doors, and walls were lined up with the sun's path. This helped them know when seasons changed. Mesa Verde's Sun Temple is thought to have been an observatory.

The temple is D-shaped. Its alignment is slightly off true east-west. Its location shows that builders understood the sun and moon cycles. It lines up with the major lunar standstill. This happens every 18.6 years. It also lines up with the sunset during the winter solstice. You can see the sun set over the temple from Cliff Palace. At the bottom of the canyon is the Sun Temple fire pit. The first rays of the rising sun hit it during the winter solstice. Sun Temple is one of the largest ceremonial buildings built by the Ancestral Puebloans.

Farming and Water Systems

Starting in the 500s AD, farmers in Mesa Verde grew corn, beans, squash, and gourds. Corn and beans together gave them all the necessary proteins. When conditions were good, 3 or 4 acres (1.2 to 1.6 hectares) of land could feed a family of three or four for a year. This was if they also hunted and gathered wild plants. As corn became more important, good harvests were vital. The mesa slopes slightly south. This gave it more sun exposure. Before pottery, foods were baked or roasted. Hot rocks could boil water briefly. But beans need to boil for an hour or more. So, beans became common after pottery spread around 600 AD. Pottery made cooking beans much easier. This gave them a lot of protein and reduced the need for hunting. Beans also helped corn grow better. Legumes add nutrients to the soil. This likely increased corn yields.

Most Pueblo people used dry farming. This meant they relied on rain for their crops. But some used runoff, springs, and natural pools. Starting in the 800s, they dug and kept up reservoirs. These collected runoff from summer rains and melting snow. Some crops were watered by hand. Archaeologists think that before the 1200s, water sources were shared. But as people moved into bigger pueblos near water, control became private. It was limited to the local community.

Between 750 and 800 AD, Puebloans built two large water storage places. These were the Morefield and Box Elder reservoirs. Soon after, they built two more: the Far View and Sagebrush reservoirs. These were about 90 feet (27 meters) across. They were built on the mesa top. The reservoirs are in a line that runs for about 6 miles (9.7 km). This suggests a central plan for the system. In 2004, these four structures were named National Civil Engineering Historic Landmarks. Some recent studies suggest the Far View Reservoir was a ceremonial space, not for water.

Hunting and Gathering Food

Puebloans usually hunted small local animals. But sometimes they went on long hunting trips. Their main animal protein came from mule deer and rabbits. They also hunted Bighorn sheep, antelope, and elk. They started raising turkeys around 1000 AD. By the 1200s, turkey meat was a main food source. It replaced deer at many sites. These turkeys ate a lot of corn. This made people rely even more on corn. Puebloans wove blankets from turkey feathers and rabbit fur. They made tools like awls and needles from turkey and deer bones. Even though fish were in the rivers, they rarely ate them.

Puebloans also gathered seeds and fruits from wild plants. They searched large areas for these foods. Depending on the season, they collected piñon nuts, juniper berries, and other plants. Prickly pear fruits gave them a rare source of natural sugar. Wild seeds were cooked and ground into porridge. They used sagebrush and mountain mahogany for firewood. They also smoked wild tobacco. The Ancestral Puebloans thought all materials used and discarded were sacred. So, their trash piles were respected. Starting around 700 AD, Puebloans often buried their dead in these mounds.

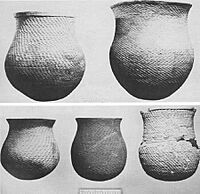

Pottery: Art and Tools

Experts disagree on whether pottery was invented in the Four Corners region. Or if it came from the south. Some clay bowls found at Canyon de Chelly suggest it started from using clay bowls to parch seeds. Repeated use made these bowls hard and waterproof. This might be the first fired pottery. Another idea is that pottery came from the Mogollon Rim area to the south. Others think it came from Mexico around 300 AD. There is no sign of ancient pottery markets. But archaeologists think potters traded decorative items between families. Cooking pots made with crushed igneous rock were stronger. Puebloans traded for them from places like Ute Mountain.

Studies show that much of the black-on-white pottery at Mesa Verde was made locally. Clays from the Dakota and Menefee Formations were used for black-on-white pottery. Mancos Formation clays were used for corrugated jars. Pottery of both types moved between different places. This suggests groups of potters interacted. Or they might have shared raw materials. Mesa Verde black-on-white pottery was made at three places: Sand Canyon, Castle Rock, and Mesa Verde. Evidence shows almost every household had someone who made pottery. Trench kilns were built away from pueblos. They were closer to firewood. Their sizes varied. Larger ones were up to 24 feet (7.3 meters) long. These might have been shared by several families. Designs were added with a Yucca-leaf brush. Paints were made from iron, manganese, beeplant, and tansy mustard.

Most pottery in 800s pueblos was for individuals or small families. But as community ceremonies grew in the 1200s, larger feast-sized pots were made. Corrugated designs appeared on Mesa Verde grey pottery after 700 AD. By 1000 AD, whole pots were made this way. This technique made a rough surface. It was easier to hold than smooth grey pottery. By the 1000s, these corrugated pots were common. They released heat better than smoother ones. This kept them from boiling over. Corrugation likely started as potters tried to copy woven baskets. Corrugated pots used different clays than other styles. Potters also chose clays and firing methods for specific colors. Mancos shale pots turned grey when fired. Morrison Formation clay pots turned white. Clays from southeastern Utah turned red when fired with lots of oxygen.

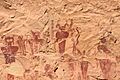

Rock Art and Murals

Rock art is found throughout the Mesa Verde region. But it's not everywhere. Some places have many examples, others none. And some periods saw lots of art, others little. Styles also changed over time. There are few examples on Mesa Verde itself. But there are many in the middle San Juan River area. This might mean the river was an important travel route and water source. Common designs in rock art include human-like figures, handprints, animal tracks, spirals, and hunting scenes. As the population dropped in the late 1200s, rock art showed more shields, warriors, and battle scenes. Modern Hopi people believe the petroglyphs at Mesa Verde's Petroglyph Point show different clans.

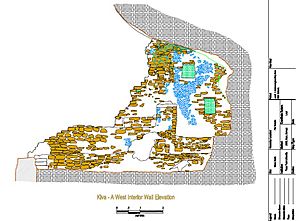

Starting in the late Pueblo II period (1020 AD) and through Pueblo III (1300 AD), Ancestral Puebloans made plaster murals. These were in their great houses, especially in kivas. The murals had painted and carved images. They showed animals, people, and designs from textiles and pottery. Some showed triangles and mounds. These might represent mountains and hills. The murals were usually on the kiva bench and went around the room. Geometric patterns like those on pottery were common. Zigzags that looked like basket stitches were also seen. The painted murals used red, green, yellow, white, brown, and blue colors. These designs were still used by the Hopi in the 1400s and 1500s.

Mesa Verde's Climate

Mesa Verde National Park has a climate with dry summers and cold winters. The average lowest temperature is about -0.1°F (-17.8°C).

The region gets rain in spring and summer. It gets snow in winter and autumn. This helps with farming and provides drinking water. The middle mesa areas are about 10°F (5°C) cooler than the mesa top. This means less water is needed for farming. The cliff dwellings were built to use the sun's energy. In winter, the sun warmed the stone buildings. Warm breezes came from the valley. The air in the canyon alcoves was 10 to 20°F (5-10°C) warmer than on the mesa top. In summer, the high cliffs protected much of the village from direct sunlight.

Nature and Landscape

The way humans affected animals and plants in the ecosystem is called anthropogenic ecology. A shift from hunting large animals like deer to smaller ones like rabbits and turkeys might mean that Puebloan hunting changed animal populations on the mesa. Studies of pack rat middens (old nests) show that plants and animals have stayed mostly the same for 4,000 years. Only a few new species like tumbleweed have appeared.

Mesa Verde National Park has Juniper and Pinyon trees. It is a mix of low desert plateaus and the Rocky Mountains.

Mesa Verde's canyons were formed by streams. These streams wore away the hard sandstone. Park elevations range from about 6,000 to 8,572 feet (1,829 to 2,613 meters) at Park Point.

How Mesa Verde Was Formed

Even though its name means "green table," Mesa Verde is not perfectly flat. It actually slopes to the south. Geologists call this a cuesta, not a mesa. This slope helped create the alcoves where the cliff dwellings are found.

Millions of years ago, layers of rock were deposited. The Mancos Shale was laid down in a deep sea. It has a lot of clay, which makes it expand when wet. This causes the ground to slide. On top of this shale are three more rock layers. The first is the Point Lookout Sandstone. This formed in shallow water as the sea pulled back. It is strong and has layers that show ancient waves.

Next is the Menefee Formation. This middle layer has coal, silt, and sandstone. It formed in swampy areas. The top of this layer is met by the Cliff House Sandstone.

The Cliff House Sandstone is the youngest rock layer. It formed after the sea was completely gone. It has a lot of sand from beaches and dunes. This gives the canyon walls their yellow color. This layer also has many fossils of shells and fish teeth. The softer shale zones in this layer are where the alcoves formed. This is where the Ancestral Puebloans built their homes.

Later, the land was pushed up. This formed the Colorado Plateau and mountains. Erosion then shaped Mesa Verde. Small streams cut into the rock, forming the deep canyons we see today. Now, the climate is drier, so these changes happen more slowly.

Rediscovering Mesa Verde

In 1776, Spanish missionaries Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante explored the Mesa Verde region. They named it for its green, tree-covered plateaus. But they never got close enough to see the ancient stone villages. They were the first Europeans to travel through much of this area.

The Utes had lived in the Mesa Verde region for a long time. A treaty in 1868 gave them ownership of all Colorado land west of the Continental Divide. Later, in 1873, a new treaty gave the Ute a strip of land in southwestern Colorado. Most of Mesa Verde is in this strip. The Ute used Mesa Verde for winter shelter. They believed the cliff dwellings were sacred ancestral sites. So, they did not live in them.

Some trappers and prospectors visited the area. John Moss, a prospector, shared his observations in 1873. The next year, Moss led photographer William Henry Jackson through Mancos Canyon. Jackson photographed a stone cliff dwelling. Geologist William H. Holmes followed Jackson's route in 1875. Reports by Jackson and Holmes were in the 1876 Hayden Survey report. These reports led to calls for studying Southwestern archaeological sites.

Virginia McClurg, a journalist, visited Mesa Verde in 1882 and 1885. She was looking for Ancestral Puebloan settlements. Her group found Echo Cliff House, Three Tier House, and Balcony House in 1885. These trips inspired her to protect the dwellings and artifacts.

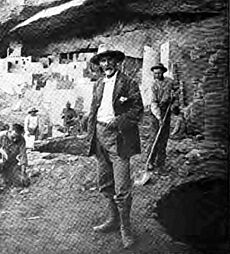

The Wetherill Family

A family of cattle ranchers, the Wetherills, became friends with members of the Ute tribe. The Ute allowed the Wetherills to bring cattle into the warmer plateaus of the Ute reservation in winter. Acowitz, a Ute member, told the Wetherills about a special cliff dwelling. He said it was "bigger than all the others." Utes did not go there because it was a sacred place.

On December 18, 1888, Richard Wetherill and cowboy Charlie Mason found Cliff Palace. They saw the ruins from the top of Mesa Verde. Wetherill gave it its name. Richard Wetherill, his family, and friends explored the ruins. They collected artifacts. Some were sold to the Historical Society of Colorado. Many were kept by the family. Frederick H. Chapin, a mountaineer and photographer, visited the Wetherills in 1889 and 1890. He wrote about the ruins in an 1890 article and a 1892 book, The Land of the Cliff-Dwellers. He included maps and photos.

Gustaf Nordenskiöld's Work

The Wetherills also hosted Gustaf Nordenskiöld in 1891. He was the son of a famous explorer. Nordenskiöld was a trained mineralogist. He used scientific methods to collect artifacts. He recorded where things were found and took many photos. He drew diagrams of sites. He also compared his findings with existing archaeological writings. He learned from the Wetherills' local knowledge. He sent many artifacts to Sweden. They are now in the National Museum of Finland. In 1893, Nordenskiöld published The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde. When he shipped his collection, it raised concerns about protecting Mesa Verde's land and resources.

Mesa Verde Becomes a National Park

In 1889, Goodman Point Pueblo became the first ancient site in Mesa Verde to be protected by the government. It was the first such site protected in the U.S. Virginia McClurg worked hard from 1887 to 1906. She told people in the U.S. and Europe how important it was to protect Mesa Verde. She got support from 250,000 women through the General Federation of Women's Clubs. She wrote poems and gave speeches. She also started the Colorado Cliff Dwellers Association.

The Colorado Cliff Dwellers wanted to protect the cliff dwellings. They aimed to get back original artifacts. They also wanted to share information about the people who lived there. Lucy Evelyn Peabody also worked to protect Mesa Verde. She met with members of Congress in Washington, D.C. Former park superintendent Robert Heyder believed the park would be more significant if Nordenskiöld had not taken so many artifacts.

By the late 1800s, it was clear Mesa Verde needed protection. People were coming and taking or selling artifacts. In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt approved the creation of Mesa Verde National Park. He also approved the Federal Antiquities Act of 1906. This park was the first created to protect a place of cultural importance. It was named "green table" because of its juniper and piñon trees.

In 1976, 8,500 acres (3,440 hectares) were made a wilderness area. These three small areas protect the Native American sites. Unlike most wilderness areas, visitors cannot access the Mesa Verde Wilderness.

Studying and Protecting the Sites

From 1908 to 1922, Spruce Tree House, Cliff Palace, and Sun Temple were made stable. Jesse Walter Fewkes led most of these early efforts. In the 1930s and 40s, Civilian Conservation Corps workers helped a lot. They dug up sites, built trails and roads, and created museum exhibits. From 1958 to 1965, the Wetherill Mesa Archaeological Project took place. This included digging, stabilizing sites, and surveys. It was the largest archaeological effort in the U.S. They dug up Long House and Mug House.

In 1966, Mesa Verde was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1987, the Mesa Verde Administrative District was also listed. It became a World Heritage Site in 1978. Sunset magazine named Mesa Verde National Park "the best cultural attraction" in the Western United States in 2015.

Working with Local Tribes

There were discussions between environmental groups and local tribes about the ruins. These started even before the park was officially created. In 1911, the U.S. government wanted more land for the park. This land belonged to the Ute Indians. The Utes did not want to trade their best land. Frederick Abbott, working with an Indian Office official, said the "government was stronger than the Utes." He said the government had the right to take land with old ruins for public use. The Utes felt they had no choice. They agreed to trade 10,000 acres (4,047 hectares) on Chapin Mesa for 19,500 acres (7,891 hectares) on Ute Mountain.

The Utes continued to work with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. They wanted to prevent more Ute land from becoming part of the park. In 1935, the BIA tried to get back some of the land traded in 1911. Later, park superintendent Jesse L. Nusbaum admitted that the Ute Mountain land traded in 1911 already belonged to the tribe. This meant the government had traded land they didn't own.

Other issues came up because of park activities. In the 1920s, the park started "Indian ceremony" performances for tourists. However, these ceremonies did not truly show the traditions of the Ancient Puebloans. They also did not show the traditions of the modern Ute people. Navajo day laborers performed these rituals. This led to questions about cultural accuracy. There were also questions about fair pay for the Navajo dancers. And why local American Indians were not hired for other jobs in the park. The Ute Mountain Ute tribe also received little money from the park. This was despite their land trade making much of the park possible.

Park Services for Visitors

The entrance to Mesa Verde National Park is on U.S. Route 160. It is about 9 miles (14 km) east of Cortez. The park covers 52,485 acres (21,240 hectares). It has 4,372 recorded sites. This includes over 600 cliff dwellings. It is the largest archaeological preserve in the U.S. It protects some of the most important ancient sites in the country. The park started a program in 1995 to conserve archaeological sites. It studies how sites were built and used.

The Mesa Verde Visitor and Research Center opened in December 2012. It is just off Highway 160. Chapin Mesa is the most popular area. It is 20 miles (32 km) past the visitor center. Mesa Verde National Park is a federal area. So, federal National Park Service Law Enforcement Rangers handle all law enforcement, medical, and fire duties. The park's post office has the ZIP code 81330.

Access to park facilities changes with the seasons. Three cliff dwellings on Chapin Mesa are open to the public. The Chapin Mesa Museum is open all year. Spruce Tree House is closed due to rockfall danger. Balcony House, Long House, and Cliff Palace require tickets for ranger-guided tours. Many other dwellings can be seen from the road but are not open to visitors. The park has hiking trails and a campground. During busy season, there are places for food, fuel, and lodging. These are not available in winter.

The park's early buildings on Chapin Mesa are important for their architecture. Built in the 1920s, the Mesa Verde administrative complex was one of the first examples of the Park Service using designs that fit the local culture. This area was named a National Historic Landmark District in 1987.

Wildfires and Their Impact

From 1996 to 2003, the park had several wildfires. Many were started by lightning during droughts. These fires burned 28,340 acres (11,469 hectares) of forest. This is more than half the park. The fires also damaged many archaeological sites and park buildings. Some fires were Chapin V (1996), Bircher and Pony (2000), Long Mesa (2002), and the Balcony House Complex fires (2003). The Chapin V and Pony fires destroyed two rock art sites. The Long Mesa fire almost destroyed the museum and Spruce Tree House. Spruce Tree House is the third largest cliff dwelling.

Before these fires, archaeologists had surveyed about 90% of the park. Thick plants and trees hid many ancient sites. But after the fires, 593 new sites were found. Most of these date to the Basketmaker III and Pueblo I periods. The fires also revealed many water systems. These included 1,189 check dams, 344 terraces, and five reservoirs. These date to the Pueblo II and III periods. In 2008, the Colorado Historical Society invested money in a project. This project studied culturally modified trees in the park.

Ute Mountain Tribal Park

The Ute Mountain Tribal Park is next to Mesa Verde National Park. It covers about 125,000 acres (50,586 hectares) along the Mancos River. Hundreds of ancient sites are preserved here. These include cliff dwellings, petroglyphs, and wall paintings. They show Ancestral Puebloan and Ute cultures. Native American Ute tour guides share information about the people, culture, and history of the park. National Geographic Traveler named it one of "80 World Destinations for Travel in the 21st Century." It was one of only nine places chosen in the U.S.

Key Sites to See

Besides the famous cliff dwellings, Mesa Verde has many ruins on top of the mesas. Some you can visit include the Far View Complex and Cedar Tree Tower on Chapin Mesa. Also, the Badger House Community on Wetherill Mesa.

Balcony House

Balcony House is on a high ledge facing east. Its 45 rooms and 2 kivas would have been cold in winter. Visitors on ranger-guided tours climb a 32-foot (9.8-meter) ladder. Then they crawl through a small 12-foot (3.7-meter) tunnel. The exit is a series of toe-holds in the cliff. This was likely the only way in and out for the ancient people. This made the village easy to defend. One log was dated to 1278 AD. So, it was likely built not long before people left Mesa Verde. Jesse L. Nusbaum officially dug up the site in 1910. He was the first National Park Service Archeologist. Visitors can only enter Balcony House with a ranger-guided tour. This tour involves climbing ladders and crawling through a tunnel.

Cliff Palace

This multi-story ruin is the most famous cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde. It is in the largest alcove in the center of the Great Mesa. It faces south and southwest. This gave it more warmth from the sun in winter. The dwelling is over 700 years old. It is built of sandstone, wooden beams, and mortar. Many rooms were painted brightly. Cliff Palace was home to about 125 people. It was likely an important part of a larger community. This community had sixty nearby pueblos. They housed 600 or more people combined. Cliff Palace has 23 kivas and 150 rooms. It is the largest cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde National Park.

Long House

Long House is on Wetherill Mesa. It is the second-largest Puebloan village. About 150 people lived there. The site was dug up from 1959 to 1961. This was part of the Wetherhill Mesa Archaeological Project. Long House was built around 1200 AD. It was lived in until 1280 AD. The cliff dwelling has 150 rooms, a kiva, a tower, and a central plaza. Its rooms are not clustered like other cliff dwellings. Stones were used without shaping. Two ledges above have storage space for grain. One ledge seems to have a lookout with small holes. A spring is nearby. Seeps are at the back of the village.

Other Important Houses

- Mug House is on Wetherill Mesa. It has 94 rooms and a large kiva. A reservoir is nearby. It got its name from four mugs found there.

- Oak Tree House and nearby Fire Temple can be visited on a 2-hour ranger-guided hike.

- Spruce Tree House is the third-largest village. It is near a spring. It had 130 rooms and eight kivas. It was built between 1211 and 1278 AD. About 60 to 80 people lived there. It is well preserved because of its protected location. The short trail to Spruce Tree House starts at the Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum.

- Square Tower House is on the Mesa Top Loop Road driving tour. Its tower is the tallest structure in Mesa Verde.

Images for kids

-

Archaic pictographs, around 2500 BC, Sego Canyon, Utah

See also

In Spanish: Parque nacional Mesa Verde para niños

In Spanish: Parque nacional Mesa Verde para niños