Royal Scots Greys facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Royal Regiment of Scots DragoonsRoyal North British Dragoons Royal Scots Greys |

|

|---|---|

Cap badge of the Scots Greys

|

|

| Active | 1678–1971 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Line Cavalry |

| Role | Armoured |

| Size | Regiment |

| Part of | Royal Armoured Corps |

| Garrison/HQ | Redford Barracks, Edinburgh |

| Nickname(s) | "Birdcatchers" "The Bubbly Jocks" |

| Motto(s) | Nemo me impune lacessit (Nobody touches me with impunity) Second to None |

| Colours | Blue facings with gold lace (for officers) or yellow lace (for other ranks) |

| March | Quick (band) – Hielan' Laddie Slow (band) – The Garb of Old Gaul; (pipes & drums) – My Home |

| Insignia | |

| Tartan |  |

The Royal Scots Greys was a famous cavalry regiment in the British Army. They served from 1707 until 1971. Then, they joined with another regiment, the 3rd Carabiniers (Prince of Wales's Dragoon Guards). Together, they formed the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

The regiment started in 1678 with three small groups of Scottish soldiers on horseback. In 1681, these groups became one unit called The Royal Regiment of Scots Dragoons. By 1694, they were known as the 4th Dragoons. They already rode grey horses and people called them the Grey Dragoons. In 1707, their name changed to The Royal North British Dragoons. But everyone still called them the Scots Greys. In 1713, they became the 2nd Dragoons as the English and Scottish armies joined. Their nickname became official in 1877 as the 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys). In 1921, this was changed to The Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons). They kept this name until July 2, 1971, when they joined with the 3rd Carabiniers.

Contents

- How the Scots Greys Began

- Grey Horses, Red Coats, and European Wars (1693–1714)

- Keeping Order and Fighting Jacobites (1715–1741)

- Home Service and Waterloo (1764–1815)

- Peace and the Crimean War (1816–1856)

- Home Service, Egypt, and Boer War (1857–1905)

- The Great War (1914–1918)

- Second World War (1939–1945)

- Post-War and Amalgamation (1946–1971)

- Regimental Traditions

- Battle Honours

- Images for kids

How the Scots Greys Began

The Royal Scots Greys started as three groups of dragoons. Dragoons were soldiers who rode horses but fought like infantry. They used muskets, and their officers carried swords or spears called partisans. The first uniform was a grey coat. But there's no record that their horses had to be grey at first.

On May 21, 1678, the first two groups were formed. A third group joined on September 23. These were the first mounted soldiers in Scotland for the King. They were used to keep order and stop certain religious meetings. In June 1679, some people fought back. This led to the Battle of Bothwell Bridge.

In 1681, three more groups were added. This created the Royal Regiment of Scots Dragoons. Back then, regiments often belonged to their colonel. So, their names changed when a new colonel took over.

King Charles II's commander in Scotland, Thomas Dalziel, became their first Colonel. In 1685, the regiment fought against a Scottish uprising called Argyll's Rising. Later that year, Charles Murray became the Colonel.

Before the Glorious Revolution in 1688, Scotland was restless. The regiment tried to stop the rebellion. They were in London when William of Orange arrived. In December, Sir Thomas Livingstone became the new Colonel. The regiment, now called Livingstone's Regiment of Dragoons, supported William's new government. They fought against those still loyal to the old king. In 1692, William III officially named them 'Royal' and ranked them as the 4th Dragoons.

Grey Horses, Red Coats, and European Wars (1693–1714)

In 1693, King William III saw the regiment. He noticed they all rode grey horses. Some think these horses came from a Dutch cavalry unit. Their original grey coats were changed to red, or scarlet, with blue trim. This showed their "Royal" status.

In 1694, they moved to the Netherlands for the Nine Years' War. They scouted for information but didn't fight in any major battles. After the war ended in 1697, they returned to Scotland. When the War of the Spanish Succession began, they went back to Flanders in 1702. They were part of Marlborough's army. They fought actively in 1702 and 1703. They even captured a large shipment of gold in 1703.

During Marlborough's march in 1704, the Scots Greys were part of a dragoon brigade. They fought on foot at the Battle of Schellenberg. Then, they fought at the Battle of Blenheim on July 2, 1704. Even though they were in heavy fighting, no one died, but many were wounded.

At the Battle of Elixheim in 1705, the Scots Greys joined a huge cavalry charge. This charge broke through the French lines. At Ramillies in May 1706, they captured the flags of an elite French regiment.

They were renamed the Royal North British Dragoons. Their next big fight was the Battle of Oudenarde. At the Battle of Malplaquet in September 1709, they captured the flag of the French Household Cavalry. This was their last major battle before the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713.

After the Acts of Union in 1707, the English and Scottish armies combined. There were debates about which regiments were older. The Scots Greys were supposed to be the first dragoon regiment. But this caused protests. So, a deal was made. An English dragoon regiment became first, and the Scots Greys became the 2nd Royal North British Dragoons. This is where their motto Second to None came from.

Keeping Order and Fighting Jacobites (1715–1741)

Back in Britain, the Scots Greys helped police the countryside in Scotland. In 1715, the Earl of Mar started the Jacobite rising. He supported the "Old Pretender," James Stuart. The Scots Greys stayed loyal to the King. They helped put down the uprising. They fought at the Battle of Sheriffmuir on November 13, 1715.

At Sheriffmuir, the Scots Greys were on the right side of the King's army. They attacked the left side of the Jacobite army. They surprised the Highlanders by going around a swamp. The Scots Greys charged repeatedly into the confused Jacobite soldiers. They chased the fleeing Jacobites for almost two miles. The Jacobites were trapped by the river Allan. The Scots Greys gave them little mercy. It's said the Duke of Argyll told them to "Spare the poor blue bonnets!" But the Scots Greys kept fighting. The rest of the King's army didn't do as well. The battle ended in a draw.

Even though the battle was undecided, it stopped the Jacobite advance. For the next four years, the Scots Greys continued to fight Jacobite supporters in Scotland. After the uprising ended in 1719, the Scots Greys went back to policing Scotland. The next 23 years were quiet for the regiment.

War in Europe: Austrian Succession (1740–1748)

From 1740 to 1748, the War of the Austrian Succession took place. The Scots Greys moved to Flanders in 1742. They protected the area around Ghent. The regiment fought at Dettingen in June 1743. This was the last time a British king led troops in battle. In May 1745, they fought at the Battle of Fontenoy. The cavalry didn't do much, except cover the army's retreat.

When the 1745 Rising began, many British units went back to Scotland. But the Scots Greys stayed in Flanders. They fought at the Battle of Rocoux on October 11, 1746. After the Battle of Culloden, British units returned to Europe.

The French won another battle at Lauffeld on July 2. The Scots Greys took part in a famous cavalry charge. This charge helped the rest of the army retreat. But the Scots Greys lost almost 40% of their men. By the time they were back to full strength, the war ended in 1748. The Scots Greys then returned to Britain.

Seven Years' War (1756–1763)

The Scots Greys spent seven quiet years in Britain. A big change happened in 1755. A "light company" was added to the regiment. These soldiers were on lighter, faster horses.

Soon after, Britain joined the Seven Years' War. The light company was separated from the Scots Greys. It joined other light cavalry units to raid the French coast. One famous raid was on St. Malo in June 1758. They destroyed ships there.

The rest of the regiment went to Germany in 1758. They joined an army led by Prince Ferdinand. The Scots Greys fought at the Battle of Bergen on April 13, 1759. The British and their allies lost. The cavalry, including the Scots Greys, covered the retreat.

After the defeat, the British army regrouped. They met the French army at the Battle of Minden on August 1, 1759. The Scots Greys were held back at first. But when the French started to retreat, the Scots Greys and other cavalry chased them.

The next year, 1760, the British cavalry was led more bravely. At the Battle of Warburg on July 31, the Scots Greys charged. They broke the French left side. Three weeks later, the Scots Greys and another regiment defeated French cavalry near Zierenberg.

In 1761, the Scots Greys patrolled and fought small battles. They were with the main army at the Battle of Villinghausen in July.

In 1762, the Scots Greys continued to raid French troops. The two armies met at the Battle of Wilhelmsthal on July 24. The Scots Greys helped chase the French. They captured many prisoners and supplies.

This was the Scots Greys' last major battle of the war. The war ended in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris. The Scots Greys returned home to Britain.

Home Service and Waterloo (1764–1815)

Between 1764 and 1815, the Scots Greys stayed in Britain. They didn't fight in the American Revolutionary War. Except for a short time in Flanders (1793–94), they didn't see action in the French Revolutionary or Napoleonic Wars until 1815.

During this time, the regiment changed. They started to look more like cavalry, not mounted infantry. Drummers were replaced with trumpeters in 1766. Two years later, they got the tall bearskin hat that stayed part of their uniform until 1971. They also added a light dragoon section. But this was later removed to form a new regiment in 1779.

Fighting in the Low Countries (1793–1795)

With the French Revolution in 1789, tensions grew. The Scots Greys added four new troops, making nine troops of 54 men each, in 1792. Four troops went to Europe in 1793. They joined the Duke of York's army in the Low Countries. They helped in the siege of Valenciennes. Then, they were part of the failed siege of Dunkirk.

After Dunkirk, the Scots Greys screened the Duke of York's army. Their next big fight was at Willems on May 10, 1794. The Scots Greys, with other regiments, charged the French infantry. The French formed squares to defend themselves. But the Scots Greys charged right into one square and broke it. This was amazing! It made the other French soldiers lose courage. The Scots Greys helped defeat three French battalions and capture 13 cannons. This was the last time British cavalry broke an infantry square without artillery support until 1812.

Despite this victory, the Allied Army lost the Battle of Tourcoing on May 18, 1794. The British Army then retreated. The Scots Greys helped cover the retreat through the Low Countries. By spring 1795, they returned to England. The nine troops were reunited, and one troop was disbanded.

Even though they fought bravely, the Scots Greys didn't see action again until 1815.

The Battle of Waterloo (1815)

This changed when Napoleon escaped from Elba. The Scots Greys grew to 10 troops, with 946 officers and men. This was their largest size ever. Six troops went to Europe. They joined the Duke of Wellington's army. The Scots Greys were part of the Union Brigade. This brigade included the Royal Dragoons and the Inniskillings Dragoons.

The Scots Greys missed the Battle of Quatre Bras after a long ride. They arrived as the French were retreating.

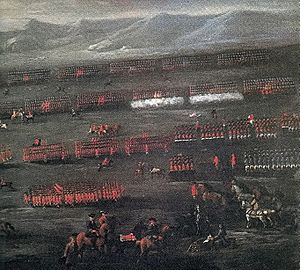

On the morning of June 18, 1815, the Scots Greys were on the left side of Wellington's army. The cavalry commander, the Earl of Uxbridge, held them back. But the French infantry was attacking hard. Uxbridge ordered the Household and Union Brigades to attack. The Scots Greys were told to stay in reserve at first.

As the other British cavalry attacked, Lieutenant-Colonel Hamilton saw British soldiers falling back. On his own, he ordered his regiment forward. The ground was muddy and uneven, so they walked at first. They passed through their own soldiers. The Scots Greys' arrival helped rally the other soldiers, who then attacked the French. Even without a full gallop, the Scots Greys' charge was too strong for the French. A soldier who was there wrote, "the Scots Greys actually walked over this column."

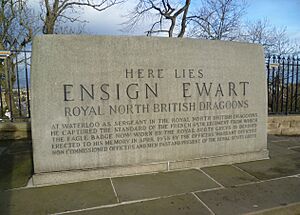

As the Scots Greys fought through the French, Sergeant Charles Ewart saw the eagle (battle standard) of a French regiment. He captured it! Sergeant Ewart was ordered to take the eagle away so the French couldn't get it back. For his bravery, he was promoted.

After defeating the French column, the Scots Greys were disorganized. Their commanders couldn't get them back in order. Instead of regrouping, the Scots Greys kept going. They galloped towards another French division. Some French soldiers had time to form squares. Musket fire hit the Scots Greys as they swept around the French. They couldn't break these squares. But by turning to face the Scots Greys, the French exposed themselves to the 1st Royal Dragoons. The Royal Dragoons attacked and captured or routed many French soldiers.

The Scots Greys were tired and disorganized. They found themselves in front of the main French lines. Their horses were exhausted. French cavalry then counter-attacked.

As their commander tried to rally his men, he was attacked and captured. Some Scots Greys tried to rescue him. But the French soldier killed him and three of the Scots Greys. The French cavalry drove the Union Brigade back. French artillery also fired on them.

The remaining Scots Greys retreated to the British lines. They reformed and helped by firing their carbines. In total, the Scots Greys lost 104 dead, 97 wounded, and 228 horses. They could only form two weak squadrons.

After Waterloo, the Scots Greys chased the French army. They stayed in Europe until 1816 as part of the army occupying France.

Peace and the Crimean War (1816–1856)

Between 1816 and 1854, the Scots Greys stayed in Britain. They moved from place to place, sometimes helping local police.

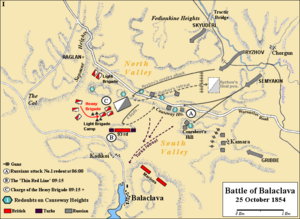

This peaceful time ended with the war with Russia. Britain, France, and Sardinia sent forces to the Black Sea. Their goal was to capture Sevastopol in Crimea. The Scots Greys arrived in Crimea in 1854. They were part of the Heavy Brigade.

On October 25, 1854, the Heavy Brigade supported the siege of Sevastopol. Russian forces attacked to disrupt the siege and threaten the supply base at Balaclava. The Russians had about 25,000 men. The British had only about 4,500.

As the Russians attacked, the Scots Greys watched. They saw the Russian force charge the 93rd Highlanders. But the Highlanders held their ground, forming a "thin red streak tipped with a line of steel".

The Scots Greys' commander, Scarlett, ordered his brigade to form two columns. The Scots Greys were in the left column. As they moved, Scarlett learned of more Russian cavalry. He ordered his brigade to turn around. The Scots Greys ended up in the front line. Even with the Russians coming, Scarlett waited for his men to form up.

The Russian cavalry on the hills numbered about 3,000. The Scots Greys and other British dragoons at the bottom had about 800 men. When ready, Scarlett ordered the advance. The Scots Greys had to pick their way through an abandoned camp. They sped up to catch Scarlett. For some reason, the Russian commander stopped his cavalry on the hill.

Scarlett and his small group were the first to reach the Russian cavalry. The rest of the brigade followed. As they got closer, they were fired upon. The Scots Greys' commander was killed. The Scots Greys finally caught up with the other regiments just before the Russians. They began to gallop. As one regiment shouted their battle cry, observers said the Scots Greys made an "eerie, growling moan." The Scots Greys charged through the Russian cavalry.

Both sides were disorganized. The Scots Greys' adjutant realized they needed to regroup. They reformed and charged again into the Russians. Other British regiments arrived and helped push the Russians back. The Russian cavalry had enough and retreated up the hill.

The whole fight lasted about 10 minutes. The Heavy Brigade had 78 casualties. They caused 270 casualties to the Russians. More importantly, the Scots Greys helped defeat a Russian cavalry division. This ended the threat to the British supply base. The Scots Greys then watched as the Light Brigade made their ill-fated charge. As the Scots Greys returned, Colonel Campbell of the Highlanders praised them. He said he would be proud to serve in their ranks. Two Scots Greys, Sergeant Major John Grieve and Private Henry Ramage, were among the first to receive the Victoria Cross for their bravery. For the rest of the war, the Scots Greys had little to do.

Home Service, Egypt, and Boer War (1857–1905)

By 1857, the regiment was back in Britain. They spent the next fifty years on peaceful duties. In 1877, their nickname became official. They were called the 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys).

Some individual Scots Greys served in other units. A large group of two officers and 44 men joined the Heavy Camel Regiment. They went to relieve Gordon at Khartoum. They fought at the Battle of Abu Klea. Thirteen of them were killed, and three died of disease.

In 1899, the Second Anglo-Boer War began. The Scots Greys were sent to Cape Town. Much had changed in warfare. They no longer wore red coats and bearskin hats. They now fought in khaki. They even dyed their grey horses khaki to blend in with the landscape.

The regiment arrived in December 1899. They guarded British supply lines. When Lord Roberts began his advance, the Scots Greys joined the 1st Cavalry Brigade. They were joined by two squadrons of Australian horsemen.

The Scots Greys helped relieve Kimberly. They also fought during the advance to Bloemfontein and later Pretoria. This included the Battle of Diamond Hill.

After Pretoria was captured, the Scots Greys went to free British prisoners. The prisoners were at Waterval POW camp. As the Scots Greys approached, the prisoners saw them. The British prisoners overpowered their guards. They rushed out to meet the Scots Greys. A Boer commander, Koos de la Rey, tried to stop the rescue. But he decided to retreat rather than fight over the prison camp.

The fall of Pretoria marked the end of the second phase of the war. The third phase was a guerrilla campaign by the Boers. The Scots Greys were constantly on the move.

One squadron was left at Uitval. They were joined by other soldiers. The Scots Greys came under a new commander. He reduced the guards. This allowed Boer commandos to attack on July 10, 1900. Most of the squadron was captured.

After this disaster, the Scots Greys rejoined the 1st Cavalry Brigade. From February to April 1901, they swept through the Transvaal. They captured or destroyed many Boer supplies. Then, they swept for guerrillas in the Vaal River valley. They heard about a British defeat at Battle of Bakenlaagte. The Scots Greys and other units chased the Boers. They killed many who had fought at Bakenlaagte.

The Scots Greys continued to fight the guerrilla campaign. They captured Commandant Danie Malan. Finally, the last of the Boers agreed to peace on May 31, 1902. The Scots Greys stayed for three more years. They helped guard the colony from Stellenbosch. They returned to Britain in 1905.

The Great War (1914–1918)

Between the Boer War and World War I, the Scots Greys were updated. They got new rifles and swords. The British Army debated what cavalry would do in the next war. In 1914, the Scots Greys had three squadrons. Each squadron had four troops with 33 men. When war began in August 1914, the Scots Greys joined the 5th Cavalry Brigade.

At first, the 5th Cavalry Brigade worked on its own. But on September 6, 1914, it joined a larger command. This command became the 2nd Cavalry Division. The Scots Greys stayed with this division for the rest of the war.

First Contact and Retreat (1914)

The regiment arrived in France on August 17, 1914. Soon after, they were told to dye their horses. Their grey horses were too easy to spot. Also, the grey horses made the regiment too easy to identify. For the rest of the war, their grey horses were dyed dark chestnut.

They first met the German army on August 22, 1914, near Mons. The Scots Greys fought on foot and pushed back a German unit. The Germans thought they had met a whole brigade. As the British army had to retreat, the Scots Greys became part of the rear guard. They protected the retreating troops. After the Battle of Le Cateau, the Scots Greys helped stop the German chase on August 28.

Once the British army reorganized, they fought in the Battle of the Marne in September 1914. The Scots Greys went from covering a retreat to screening an advance. The British advance stopped at the Battle of Aisne. British and German forces fought to a standstill.

Race to the Sea and Ypres (1914)

After leaving the trenches at the Aisne, the Scots Greys went north to Belgium. They were part of the lead units as the British and Germans raced to outflank each other. The Scots Greys joined the newly formed 2nd Cavalry Division.

As the front lines became stuck, more riflemen were needed. The Scots Greys were used mostly as infantry. They fought in the Battles of Messines and Ypres. The regiment was almost always fighting from the start of the First Battle of Ypres until it ended.

Trench Warfare (1915–1916)

The Scots Greys returned to the trenches in 1915. Because there weren't enough infantry soldiers, the regiment continued to fight on foot. They stayed on the front line for almost all of the Second Battle of Ypres. Their losses in that battle forced them into reserve for the rest of the year. Scottish newspapers reported that the horses were painted khaki because their grey coats were too visible to German gunners.

By January 1916, the Scots Greys were back in action. They contributed a troop to the front line. This troop raided and countered German raids.

When new armies arrived, the Scots Greys gathered for the summer offensive. They were held in reserve for a breakthrough that never came during the Battle of the Somme.

As the war continued, more mobile firepower was needed. The Scots Greys added a machine gun squadron.

Arras and Cambrai (1917)

British generals still hoped to use cavalry in their traditional roles. The Battle of Arras showed this was difficult.

Starting in April, the Scots Greys fought near Wancourt. In three days of fighting, they suffered heavy losses of men and horses. After resting, the Greys raided German positions at Guillermont Farm. The raid succeeded. The Scots Greys killed 56 and captured 14 Germans with few losses.

In November 1917, the Scots Greys supported the tank attack at the Battle of Cambrai. They were meant to exploit a breakthrough. But the breakthrough didn't happen. The Scots Greys found themselves fighting on foot again. A bridge needed for their advance was accidentally destroyed by a tank. So, they fought as infantry.

St. Quentin and Final Offensive (1918)

After the battles of 1917, the Scots Greys were near the St. Quentin canal. They saw the German offensive push across the canal. The Scots Greys held their ground but were in danger of being surrounded. The German attacks were very fast. In the confusion, parts of the Scots Greys got lost. They fought with other regiments, covering the retreat. When the German attacks slowed down in April, the Scots Greys were pulled back to regroup.

From May to June 1918, the Scots Greys were in reserve. In August, they moved forward for the Battle of Amiens. They supported the Canadian Corps' attack.

With the victory at Amiens, the British army began its final offensive. In August and September 1918, the Scots Greys often worked in small groups. They scouted, delivered messages, and patrolled. As the army neared the Sambre river, the Scots Greys checked river crossings. But many soldiers got sick with the influenza. In a few days, only one small company of men was healthy enough to fight.

At the time of the Armistice, the Scots Greys were at Avesnes. To enforce the peace, they crossed into Germany on December 1, 1918. But they were almost immediately dismounted. By early 1919, the Scots Greys had only 7 officers and 126 other ranks. This was about the size of one of their pre-war squadrons. After almost five years, the Scots Greys returned to Britain on March 21, 1919.

Between the Wars (1919–1939)

For the next year, the Scots Greys stayed in Britain. They were renamed "The Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons)". Even though tanks were used in World War I, many officers still believed horses had a place in battle. So, the Scots Greys kept their horses when they went to India in 1922. They served there for six years.

Back in Britain, the Scots Greys faced budget problems. In 1933, they marched through Scotland to get publicity. They even crossed the Cairngorm Mountains. Despite low budgets, the Scots Greys, like other cavalry regiments, were finally re-equipped. Each troop now had an automatic weapons section.

Still on horses, the Scots Greys went to Palestine in October 1938. They helped stop the Arab Revolt. Most of the time, they kept peace between Jewish settlers and Arabs.

Second World War (1939–1945)

Palestine and Syria (1939–1941)

Still in Palestine, the Scots Greys were brought to full strength when war was declared against Germany. Even though German attacks showed tanks were powerful, the Scots Greys still had horses.

As the British army fought in France in 1940, the Scots Greys stayed in the Middle East. They policed the area. In February 1940, the regiment made its last mounted cavalry charge on horseback. They were called to stop Arab rioters.

First, the Scots Greys became a motorized regiment, using wheeled vehicles. Parts of the Scots Greys and another regiment formed a combined cavalry unit. They reinforced the invasion of Vichy French-held Syria and Lebanon. The rest of the regiment stayed near Jerusalem. The combined regiment fought in most of the battles, including the Battle of Kissoué. There, they held off a French tank counter-attack.

After the campaign, the Scots Greys had a final review as a cavalry regiment. Soon after, their horses were replaced. The soldiers, who had been dragoons, were retrained. They became drivers, loaders, and gunners for tanks. They became an armoured regiment. In September 1941, they received their first tanks, the Stuart tank.

Egypt, Libya, Tunisia (1942–1943)

After becoming an armoured unit, the Scots Greys joined the Eighth Army in Egypt. Their Stuart tanks were taken away, and they learned to use the Grant tank.

The Scots Greys were ready for combat but didn't fight around Tobruk in 1942. Many other tank units were damaged. So, the Scots Greys had to give their tanks to other units. In July 1942, the Scots Greys finally fought. They had a mix of Grant and Stuart tanks. They were temporarily attached to another brigade. They were held in reserve. The Scots Greys counter-attacked German forces. They fought the German Panzer IV tanks and drove them back.

A month later, the Scots Greys fought at the Second Battle of El Alamein. They were part of the 7th Armoured Division. They took part in a diversionary attack. This attack pinned down German and Italian tank divisions. This allowed other parts of the Eighth Army to attack elsewhere. The Scots Greys helped destroy an Italian division on November 4, 1942. At Fuka, the Scots Greys found the division's artillery. They charged forward as if still on horses. They captured eleven cannons and about 300 prisoners. They only lost one tank.

The Scots Greys chased Rommel's army for the next month and a half. Their main problem was the condition of their tanks. Some could be repaired, others had to be replaced. By the end of the month, they had a mix of Grant, Sherman, and Stuart tanks. In December, the Eighth Army fought the Battle of El Agheila. On December 15, 1942, the Scots Greys fought German tanks near Nofilia. They had fewer tanks due to breakdowns and losses. They entered the village, capturing 250 German soldiers. They then met about 30 German tanks. The tank battle was undecided. Each side lost 4 tanks, but the Scots Greys recovered 2 of theirs. The Germans retreated.

As the chase continued, the Scots Greys saw little tank-on-tank action. Rommel's army retreated into Tunisia. By January 1943, the Scots Greys were pulled from the front to refit.

Italy (1943)

The Royal Scots Greys were re-equipped with Sherman II tanks. They continued to train during the short Sicilian campaign. They didn't see action until the Salerno landings (Operation Avalanche) in September 1943. This was part of the Italian Campaign. The regiment was assigned to the 23rd Armoured Brigade.

Soon after landing, the Royal Scots Greys fought German forces during the advance to Naples. The regiment's three squadrons were split up. They supported three infantry brigades. The Scots Greys helped defeat German counter-attacks. On September 16, the Scots Greys fought as a full regiment. They helped stop and push back a German tank division. This allowed the British X Corps to advance. The regiment continued to push north until they stopped at the Garigliano River. In January 1944, the regiment gave its tanks to other units. They were transferred back to England.

North-West Europe (1944–1945)

The regiment spent the first half of 1944 training for the invasion of Europe. On June 7, 1944, the first three tanks of the regiment landed on Juno Beach. As part of the Battle of Caen, the Scots Greys fought for Hill 112. During this fighting, the Scots Greys realized their Sherman II tanks were not as good as the new German Panthers. In one case, a Sherman hit a Panther four times from 800 yards. All four shots bounced off the Panther's front armour.

Once the breakthrough happened, the Scots Greys chased the retreating German forces. They fought at the Falaise pocket. They crossed the Seine River. They were one of the first regiments to cross the Somme River in early September 1944. After crossing the Somme, they moved north into Belgium.

In mid-September, the Scots Greys took part in Operation Market-Garden. They fought around Eindhoven, where the 101st Airborne landed. The Scots Greys operated in the Low Countries for the rest of the year. They helped capture Nijmegen Island. They cleared German resistance along the Lower Rhine. This secured the Allied flank for the drive into Germany.

After almost six months of fighting, the Scots Greys entered Germany. This was part of Montgomery's Operation Plunder offensive. On February 26, they crossed into Germany. A little over a month later, they helped capture Bremen. On April 3, 1945, the Scots Greys supported another division. They helped them cross the Dortmund-Ems Canal. They continued to support this division as they moved across Germany towards Bremen.

As Germany collapsed, Allied commanders worried about how far the Red Army was advancing. To prevent claims over Denmark, the Scots Greys and another division were tasked with extending east past Lübeck. Even after three months of fighting, the Scots Greys covered 60 miles in eight hours. They captured the city of Wismar on May 1, 1945. They captured the town just hours before meeting the Red Army.

The final surrender by Nazi officials on May 5, 1945, ended the war for the Scots Greys. With no more fighting, the Scots Greys immediately started collecting horses. They wanted to set up a regimental riding school in Wismar.

Post-War and Amalgamation (1946–1971)

After Japan surrendered, the Scots Greys took on garrison duty. From 1945 to 1952, they stayed in the British sector of Germany. In 1952, the regiment went to Libya. They returned to Britain in 1955. They moved between barracks in Britain and Ireland. Then, they returned to Germany in 1958.

In 1962, the Scots Greys moved again. This time, they went to help with the Aden Emergency. They stayed in Aden until 1963, guarding the border with Yemen. After a year, they returned to Germany. They stayed there until 1969.

In 1969, the Scots Greys returned home to Scotland for the last time as a separate unit. Due to army reductions, the Royal Scots Greys were scheduled to join with the 3rd Carabiniers (Prince of Wales's Dragoon Guards). They joined together on July 2, 1971, at Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh. The new unit was named The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards (Carabiniers and Greys).

Regimental Traditions

Regimental Museum

The regiment's collection is kept at the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards Museum. This museum is located in Edinburgh Castle.

Scots Greys Band

The Scots Greys were unique among British cavalry regiments because they had bagpipers. These pipers were not officially authorized by the army. But the regiment paid for them. At different times, the regiment had pipers, but they were unofficial. In the 1920s, while in India, they had their first mounted pipers. After World War II, the British Army was shrinking. Some Scottish soldiers joined other units. The Scots Greys received a small pipe band from one of these units. King George VI was very interested in the Scots Greys' pipe band. He even helped design their uniform. He gave them the right to wear the Royal Stuart tartan.

The Scots Greys band developed its own traditions. While the rest of the regiment wore black bearskin hats, the kettle drummers wore white bearskins. This tradition may have started in 1887. A common story is that it came from Tsar Nicholas II, who became their Colonel-in-Chief in 1894. But pictures show white bearskins were used before this. The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards also say this story is not true. A tradition in the regiment was for the band to play the Russian national anthem in the officers' mess. This was in honor of Tsar Nicholas II.

The Scots Greys band also had special rights. They could fly the King's personal pipe banner. The pipe major carried it when the King was present.

An album called Last of The Greys was released by the Royal Scots Greys regimental band in 1972. The song Amazing Grace from this album became a number one hit in the UK and the US. The regiments that followed the Scots Greys still release albums today.

Nicknames

Until at least World War II, the Greys had a popular nickname: "The Bird Catchers." This came from their cap badge and capturing the French Eagle at Waterloo. Another nickname was "The Bubbly Jocks," which is a Scottish term for "turkey cock."

Anniversaries and Loyal Toast

Most British Army regiments celebrate special anniversaries. These usually mark a battle where the regiment did very well. The Scots Greys celebrated their part in the Battle of Waterloo every year on June 18.

The Scots Greys, like some other British regiments, had a unique way of doing the loyal toast. Since the Glorious Revolution, officers had to toast the King. Usually, this meant standing up. But the Scots Greys did not stand for the toast. It's said this tradition started during the reign of George III. He often ate with the regiment. Because of his health, he couldn't stand for toasts. So, he allowed the officers to remain seated.

Motto

The Scots Greys had the motto "Second to none." This showed their high rank in the British Army and their fighting skill. Their official motto was from the Order of the Thistle: Nemo Me Impune Lacessit (No one provokes me with impunity).

Uniform

The British Army's heavy cavalry wore similar uniforms. But each regiment had its own unique details. The Scots Greys were different. Their most noticeable uniform feature was the bearskin cap. They were the only British heavy cavalry regiment to wear this fur hat. Before the bearskin, they were also unique. They wore a mitre cap instead of the cocked hat or tricorn worn by other cavalry regiments. The mitre cap was given to them by Queen Anne after the Battle of Ramillies in 1706. An early version of the bearskin was adopted in 1768.

Other special uniform details included a black and white zigzag band on their caps. They also wore a metal badge of the White Horse of Hanover on the back of their bearskin. And they had a silver eagle badge to remember capturing the French standard at Waterloo.

Alliances

The Scots Greys had connections with these units:

Canada—2nd Dragoons

Canada—2nd Dragoons Canada—New Brunswick Dragoons

Canada—New Brunswick Dragoons Australia—12th Light Horse

Australia—12th Light Horse New Zealand—North Auckland Mounted Rifles

New Zealand—North Auckland Mounted Rifles New Zealand—New Zealand Scottish Regiment

New Zealand—New Zealand Scottish Regiment

Battle Honours

The Scots Greys earned many battle honours for their bravery:

- War of Spanish Succession: Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, Malplaquet

- War of Austrian Succession: Dettingen

- Seven Years' War: Warburg, Willems

- Napoleonic Wars: Waterloo

- Crimean War: Balaclava, Sevastopol

- Second Boer War: South Africa 1899–1902, Relief of Kimberley, Paardeberg

- First World War: Retreat from Mons; Marne 1914; Aisne 1914; Ypres 1914, 1915; Arras 1917; Amiens; Somme 1918; Hindenburg Line; Pursuit to Mons; France and Flanders 1914–18. Mons; Messines 1914; Gheluvelt; Neuve Chapelle; St Julien; Bellewaarde; Scarpe 1917; Cambrai 1917, 1918; Lys; Hazebrouck; Albert 1918; Bapaume 1918; St Quentin Canal; Beaurevoir.

- Second World War: Hill 112; Falaise; Hochwald; Aller; Bremen; Merjayun; Alam el Halfa; El Alamein; Nofilia; Salerno; Italy 1943; Caen; Venlo Pocket; North-West Europe 1944-5; Syria 1941; El Agheila; Advance on Tripoli; North Africa 1942-3; Battipaglia; Volturno Crossing.

Images for kids

-

The Royal Scots Greys Monument in the shadow of Edinburgh Castle

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |