Suleiman the Magnificent facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Suleiman the Magnificent |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ottoman Caliph Amir al-Mu'minin Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques Kayser-i Rûm Khagan |

|||||

Portrait of Suleiman by Titian c. 1530

|

|||||

| Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Padishah) | |||||

| Reign | 30 September 1520 – 6 September 1566 | ||||

| Sword girding | 30 September 1520 | ||||

| Predecessor | Selim I | ||||

| Successor | Selim II | ||||

| Born | 6 November 1494 Trabzon, Ottoman Empire |

||||

| Died | 6 September 1566 (aged 71) Szigetvár, Kingdom of Hungary, Habsburg monarchy |

||||

| Burial | Organs buried at Turbék, Szigetvár, Hungary Body buried at Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey |

||||

| Spouse |

Mahidevran Hatun (1514; sep 1553) concubine |

||||

| Issue |

|

||||

|

|||||

| Dynasty | Ottoman | ||||

| Father | Selim I | ||||

| Mother | Hafsa Sultan | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

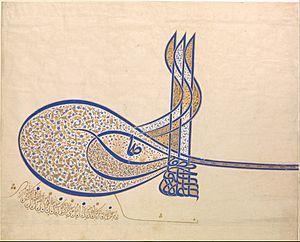

| Tughra |  |

||||

Suleiman I (born November 6, 1494 – died September 6, 1566) was the tenth and longest-reigning Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. In the West, he is known as Suleiman the Magnificent. In his own lands, he was called Suleiman the Lawgiver because he made many important changes to the laws.

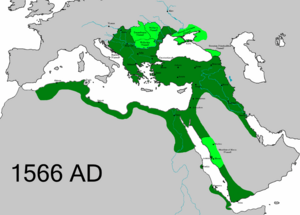

Suleiman became sultan on September 30, 1520, after his father, Selim I, passed away. During his time as ruler, the Ottoman Empire grew very large, controlling over 25 million people. He led his armies in many battles, expanding the empire's power in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.

Beyond his military achievements, Suleiman was also a great leader who improved the laws, education, and taxes in his empire. He loved art and culture, and his reign is often called the "Golden Age" of the Ottoman Empire. He was also a talented poet and a skilled goldsmith.

Suleiman broke with old traditions by marrying Hürrem Sultan, a woman from his royal harem. Their son, Selim II, became the next sultan after Suleiman's death in 1566, after 46 years of rule.

Contents

Who Was Suleiman the Magnificent?

Suleiman I is known by different names. In the West, he was called "Suleiman the Magnificent" (Muḥteşem Süleymān). In his own empire, he was known as "Suleiman the Lawgiver" (Ḳānūnī Sulṭān Süleymān). This name came from his important work in changing and improving the Ottoman legal system.

The name "Kanunî" (the Lawgiver) might have started being used for Suleiman around the early 1700s. Some people in the West mistakenly called him "Suleiman II," but this was based on a misunderstanding about an earlier prince named Süleyman Çelebi.

Early Life and Becoming Sultan

Suleiman was born in Trabzon, a city on the southern coast of the Black Sea. He was born on November 6, 1494, though the exact date is not fully certain. His mother was Hafsa Sultan, who had converted to Islam and passed away in 1534.

When he was seven years old, Suleiman began his education at the imperial Topkapı Palace in Constantinople. He studied many subjects, including science, history, literature, religion, and military strategies. As a young man, he became good friends with Pargalı Ibrahim, who was a Greek slave. Ibrahim later became one of Suleiman's most trusted advisors. At age seventeen, Suleiman became a governor in different cities like Kaffa and Manisa.

Becoming the Sultan

After his father, Selim I, died in 1520, Suleiman went to Constantinople and became the tenth Ottoman Sultan. A visitor from Venice, Bartolomeo Contarini, described Suleiman shortly after he became sultan:

The sultan is only twenty-five years [actually 26] old, tall and slender but tough, with a thin and bony face. Facial hair is evident, but only barely. The sultan appears friendly and in good humor. Rumor has it that Suleiman is aptly named, enjoys reading, is knowledgeable and shows good judgment."

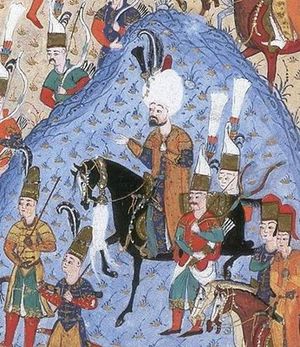

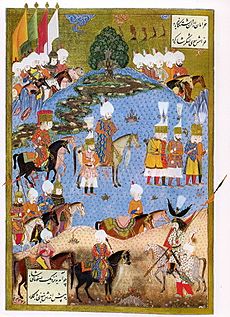

Military Campaigns and Empire Growth

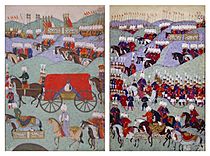

Suleiman started his reign with many military campaigns. He aimed to expand the Ottoman Empire's control.

Conquering Europe

In 1521, Suleiman planned to conquer Belgrade from the Kingdom of Hungary. This was a city his great-grandfather, Mehmed II, had tried and failed to capture. Taking Belgrade was important because the Hungarians and Croats were the last strong force blocking Ottoman expansion into Europe. Suleiman's army surrounded Belgrade and attacked it heavily. Belgrade, with only 700 defenders and no help from Hungary, fell in August 1521.

After Belgrade, Suleiman turned his attention to the island of Rhodes in the Eastern Mediterranean. Rhodes was the home base of the Knights Hospitaller. Suleiman built a large fort, Marmaris Castle, to support his navy. After a five-month Siege of Rhodes (1522), the Knights surrendered, and Suleiman allowed them to leave. This victory cost the Ottomans many soldiers due to fighting and sickness.

In 1526, Suleiman continued his campaigns in Central Europe. On August 29, 1526, he defeated King Louis II of Hungary at the Battle of Mohács. After the battle, Suleiman reportedly felt sad upon finding King Louis's body, saying he didn't wish for him to die so young.

Some Hungarian nobles wanted Ferdinand of Austria to be their king. Other nobles supported John Zápolya, who was backed by Suleiman. The Habsburgs (Ferdinand's family) took control of Hungary. In response, Suleiman marched his army through the Danube valley in 1529 and took back control of Buda. That autumn, his forces laid siege to Vienna. This was the Ottoman Empire's biggest push into the West. However, the Austrian defenders, with 16,000 soldiers, defeated Suleiman. This battle started a long rivalry between the Ottomans and the Habsburgs. His second attempt to conquer Vienna in 1532 also failed, partly due to bad weather and long supply lines.

In the 1540s, fighting in Hungary started again. In 1541, the Habsburgs tried to besiege Buda but were pushed back. The Ottomans captured more Habsburg forts. This forced Ferdinand and Charles V to sign a five-year treaty with Suleiman. Ferdinand gave up his claim to Hungary and agreed to pay Suleiman a yearly sum for the Hungarian lands he still controlled. The treaty also called Charles V "King of Spain" instead of "Emperor," showing Suleiman saw himself as the true "Caesar."

In 1552, Suleiman's forces besieged Eger, a city in northern Hungary. However, the defenders, led by István Dobó, successfully defended the Eger Castle.

Battles in the Middle East

Suleiman's father had wanted to fight Persia. At first, Suleiman focused on Europe. But after securing his European borders, he turned his attention to Persia, which followed a different branch of Islam, Shi'a. The Safavid dynasty of Persia became a major enemy.

In 1533, Suleiman sent his trusted advisor, Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha, to lead an army into eastern Asia Minor. They took back Bitlis and occupied Tabriz without a fight. Suleiman joined Ibrahim in 1534. They marched towards Persia, but the Shah avoided direct battle. Instead, the Shah used a "scorched earth" tactic, burning everything so the Ottoman army couldn't find supplies. In 1535, Suleiman made a grand entrance into Baghdad. He gained local support by restoring the tomb of Abu Hanifa, an important Islamic scholar.

Suleiman launched a second campaign against Persia in 1548–1549. Again, the Shah avoided battle and used scorched earth tactics, making it hard for the Ottoman army in the harsh winter of the Caucasus. Suleiman ended the campaign with some gains in Tabriz and the Urmia region.

In 1553, Suleiman began his third and final campaign against the Shah. After losing some land to the Shah's son, Suleiman fought back, recapturing Erzurum and destroying parts of Persia. The Shah's army continued to avoid direct fighting, leading to a stalemate. In 1555, they signed the Peace of Amasya, which set the borders between the two empires. This treaty divided Armenia and Georgia between them and gave the Ottoman Empire most of Iraq, including Baghdad.

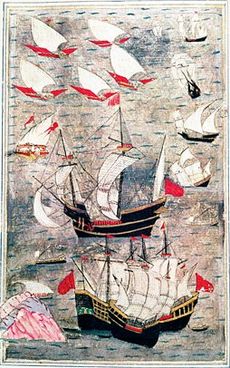

Campaigns in the Indian Ocean

Ottoman ships had been sailing in the Indian Ocean since 1518. Ottoman admirals like Hadim Suleiman Pasha traveled to ports in the Mughal Empire (modern-day India). Emperor Akbar the Great of the Mughal Empire even exchanged letters with Suleiman.

Suleiman led several naval campaigns against the Portuguese. He wanted to remove them from trade routes and restart trade with the Mughal Empire. In 1538, the Ottomans captured Aden in Yemen. This became an Ottoman base for attacks against Portuguese areas on the western coast of the Mughal Empire. The Ottomans failed to defeat the Portuguese at the siege of Diu in 1538, but they returned to Aden and made it a strong fort. From there, Sulayman Pasha took control of all of Yemen.

With strong control of the Red Sea, Suleiman successfully challenged the Portuguese over trade routes. He kept up a good level of trade with the Mughal Empire throughout the 1500s.

From 1526 to 1543, Suleiman sent over 900 Turkish soldiers to help the Somali Adal Sultanate fight during the Conquest of Abyssinia. After a war with the Portuguese, the weakened Adal Sultanate became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1559. This expanded Ottoman rule in Somalia and the Horn of Africa. It also increased their influence in the Indian Ocean, competing with the Portuguese Empire and their ally, the Ajuran Empire.

In 1564, Suleiman received a request for help from Aceh (a sultanate in modern Indonesia), who wanted Ottoman support against the Portuguese. As a result, an Ottoman expedition to Aceh was sent, providing important military help to Aceh.

The discovery of new sea trade routes by Western European countries allowed them to avoid the Ottoman trade monopoly. The Portuguese finding the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 led to a series of Ottoman-Portuguese naval wars in the Indian Ocean during the 16th century. The Ajuran Sultanate, allied with the Ottomans, challenged the Portuguese trade control by using new coins similar to Ottoman ones, showing their economic independence.

Mediterranean and North Africa

After securing his land conquests, Suleiman heard that the fortress of Koroni in Greece had been lost to Charles V's admiral, Andrea Doria. Suleiman was worried about the Spanish presence in the Eastern Mediterranean. To regain control of the seas, Suleiman appointed a skilled naval commander, Khair ad Din, known in Europe as Barbarossa. Barbarossa was tasked with rebuilding the Ottoman fleet.

In 1535, Charles V led a large army and won against the Ottomans at Tunis. This, along with a war against Venice, made Suleiman accept an offer from Francis I of France to form an alliance against Charles. Large Muslim territories in North Africa were added to the empire. The piracy by the Barbary pirates of North Africa can be seen as part of these wars against Spain.

In 1541, the Spanish led an unsuccessful expedition to Algiers. In 1542, Francis I of France wanted to renew the alliance with the Ottomans against their common enemy, the Habsburgs. In 1542, they agreed that the Ottoman Empire would send 60,000 troops and 150 ships against Charles, while France would attack Flanders and send 40 ships to help the Ottomans.

In August 1551, Ottoman naval commander Turgut Reis attacked and captured Tripoli, which had been held by the Knights of Malta since 1530. In 1553, Suleiman made Turgut Reis the commander of Tripoli. This made the city an important base for pirate raids in the Mediterranean and the capital of the Ottoman province of Tripolitania. In 1560, a strong naval force was sent to recapture Tripoli, but it was defeated in the Battle of Djerba.

Elsewhere in the Mediterranean, the Knights of Malta were attacking Muslim ships. This angered the Ottomans, who gathered another huge army to remove the Knights from Malta. The Ottomans invaded Malta in 1565, starting the Great Siege of Malta on May 18. It lasted until September 8. At first, it looked like a repeat of the battle on Rhodes, with many cities destroyed and half the Knights killed. But a relief force from Spain arrived, leading to the loss of 10,000 Ottoman troops and a victory for the Maltese people.

Legal and Government Reforms

While Suleiman was known as "the Magnificent" in the West, his own people called him Kanuni Suleiman, or "The Lawgiver." The main law of the empire was the Shari'ah, or Sacred Law, which came from Islam and could not be changed by the Sultan. However, there was another set of laws called Kanuns (canonical legislation) that Suleiman could change. These laws covered things like criminal behavior, land ownership, and taxes.

Suleiman gathered all the legal decisions made by the nine Ottoman Sultans before him. He removed repeated laws and chose between conflicting ones. Then, he created a single legal code, making sure it followed the basic laws of Islam. Suleiman, with the help of his chief legal official Ebussuud Efendi, updated these laws to fit the changing empire. When the Kanun laws were finalized, they became known as the kanun‐i Osmani, or the "Ottoman laws." Suleiman's legal code was used for over three hundred years.

The Sultan also helped protect the Jewish people in his empire. In 1553 or 1554, he issued a firman (a royal decree) that officially spoke out against false accusations of blood libels against Jews. Suleiman also created new laws for crimes and policing, setting specific fines for different offenses. For taxes, he collected money on various goods, animals, mines, trade profits, and import/export duties.

Higher medreses (schools) provided education similar to universities. Graduates from these schools became imams (religious leaders) or teachers. Educational centers were often part of larger complexes around mosques, which also included libraries, baths, soup kitchens, homes, and hospitals for the public.

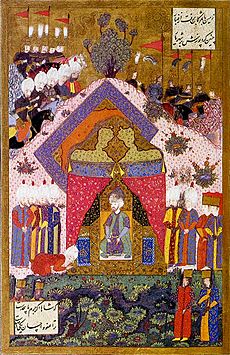

Arts and Culture Under Suleiman

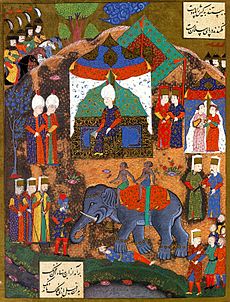

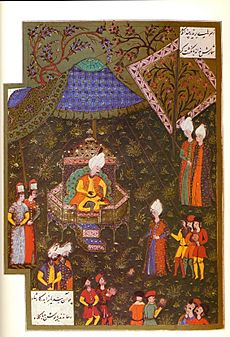

Under Suleiman's support, the Ottoman Empire entered a "golden age" of cultural development. Hundreds of imperial artistic groups, called the Ehl-i Hiref ("Community of the Craftsmen"), worked at the Imperial palace, the Topkapı Palace. After training, artists and craftsmen could move up in rank and were paid regularly. Records from 1526 show that there were 40 groups with over 600 members.

The Ehl-i Hiref attracted the most talented artists from both the Islamic world and newly conquered European lands. This led to a mix of Arabic, Turkish, and European cultures in their art. Artists working for the court included painters, book binders, furriers, jewelers, and goldsmiths. While earlier rulers were influenced by Persian culture, Suleiman's support for the arts helped the Ottoman Empire create its own unique artistic style.

Suleiman himself was a skilled poet. He wrote in Persian and Turkish using the pen name Muhibbi ("Lover"). Some of his poems have become Turkish proverbs. When his young son Mehmed died in 1543, Suleiman wrote a touching poem to remember the year. Many other great writers, like Fuzûlî and Bâkî, also created wonderful literary works during his rule. A historian noted that "at no time, even in Turkey, was greater encouragement given to poetry than during the reign of this Sultan." Suleiman's most famous poem says:

The people think of wealth and power as the greatest fate,

But in this world a spell of health is the best state.

What men call sovereignty is a worldly strife and constant war;

Worship of God is the highest throne, the happiest of all estates.

Suleiman also became famous for supporting many grand architectural projects across his empire. He wanted to make Constantinople the center of Islamic civilization. He built bridges, mosques, palaces, and various public buildings. The greatest of these were designed by his chief architect, Mimar Sinan. Sinan's work marked the peak of Ottoman architecture. He built over three hundred monuments, including his two masterpieces: the Süleymaniye Mosque and the Selimiye Mosque (finished during his son's reign). Suleiman also restored the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Walls of Jerusalem, renovated the Kaaba in Mecca, and built a complex in Damascus.

Tulips

Suleiman loved gardens. It is said that his shaykh grew a white tulip in one of the palace gardens. Nobles at court saw it and started growing their own tulips too. Soon, images of tulips were used in rugs and ceramics. Suleiman is known for growing tulips on a large scale, and it is believed that tulips spread across Europe because of him. Diplomats visiting his court were often given these flowers as gifts.

Family Life

Suleiman had two main partners: Mahidevran Hatun and Hürrem Sultan.

His Children

Suleiman I had eight sons:

- Şehzade Mahmud (1512–1520)

- Şehzade Mustafa (1515–1553), son with Mahidevran.

- Şehzade Murad (1519–1520)

- Şehzade Mehmed (1521–1543), son with Hürrem.

- Sultan Selim II (1524–1574), son with Hürrem.

- Şehzade Abdullah (c.1525–c.1528), son with Hürrem.

- Şehzade Bayezid (1527–1561), son with Hürrem.

- Şehzade Cihangir (1531–1553), son with Hürrem.

He also had two daughters:

- Raziye Sultan (c.1517–1520)

- Mihrimah Sultan (1522–1578), daughter with Hürrem. She married Rüstem Pasha in 1539 and had a daughter and a son.

His Relationship with Hürrem Sultan

Suleiman was very devoted to Hurrem Sultan. She was a woman from his harem who came from Ruthenia (part of modern-day Ukraine). Western visitors called her "Roxelana" because of her Ruthenian background and red hair. She was the daughter of an Orthodox priest, captured by Tatars, and sold as a slave in Constantinople. She rose through the ranks of the Harem to become Suleiman's favorite.

Hürrem, who was once a concubine, became Suleiman's legal wife. This was very surprising to people in the palace and the city, as it broke with Ottoman tradition. Suleiman also allowed Hürrem Sultan to stay with him at court for her entire life. This was another break from tradition, as usually, when royal heirs grew up, they and their mothers were sent to govern distant provinces and would not return unless the son became sultan.

Sultan Suleiman wrote this poem for Hürrem Sultan, using his pen name, Muhibbi:

Throne of my lonely niche, my wealth, my love, my moonlight.

My most sincere friend, my confidant, my very existence, my Sultan, my one and only love.

The most beautiful among the beautiful ...

My springtime, my merry faced love, my daytime, my sweetheart, laughing leaf ...

My plants, my sweet, my rose, the one only who does not distress me in this room ...

My Istanbul, my karaman, the earth of my Anatolia

My Badakhshan, my Baghdad and Khorasan

My woman of the beautiful hair, my love of the slanted brow, my love of eyes full of misery ...

I'll sing your praises always

I, lover of the tormented heart, Muhibbi of the eyes full of tears, I am happy.

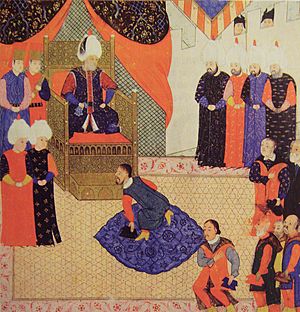

Grand Vizier Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha

Before his downfall, Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha was a very close friend and trusted advisor to Suleiman. Historians often describe their strong bond. Ibrahim was originally a Christian from Parga (in Greece). He was captured during a war and given as a slave to Suleiman around 1514. Ibrahim converted to Islam, and Suleiman quickly promoted him. He became the royal falconer, then the first officer of the Royal Bedchamber. It was said they were very close. The sultan even built Ibrahim a grand palace in Istanbul.

Ibrahim Pasha became the Grand Vizier (the highest minister) in 1523 and the commander-in-chief of all armies. Suleiman also gave Ibrahim Pasha the title of beylerbey of Rumelia, which meant he had authority over all Ottoman lands in Europe and commanded troops there during wartime. At this time, Ibrahim was only about thirty years old and didn't have much military experience. This quick rise to power was very unusual.

During his thirteen years as Grand Vizier, Ibrahim's rapid rise and great wealth made him many enemies at the Sultan's court. Suleiman's trust in Ibrahim began to weaken, especially after a disagreement between Ibrahim and the finance secretary. Ibrahim also supported Suleiman's son, Şehzade Mustafa, to be the next sultan. This caused problems with Hürrem Sultan, who wanted her own sons to inherit the throne. Eventually, Ibrahim lost the Sultan's favor. Suleiman consulted his religious judge, who suggested that Ibrahim should be put to death. The Sultan ordered assassins to kill Ibrahim in his sleep.

Who Would Be the Next Sultan?

Sultan Suleiman had six sons who lived past their childhood, four of whom were still alive in the 1550s: Mustafa, Selim, Bayezid, and Cihangir. Mustafa was the eldest, but he was not Hürrem's son. The Ottoman Empire did not have a clear rule for choosing the next sultan. This often led to princes fighting each other to prevent civil unrest.

In 1552, during a military campaign against Persia, rumors began to spread about Mustafa. The Grand Vizier, Rüstem Pasha, sent a trusted man to tell Suleiman that soldiers believed it was time for a younger prince to take the throne, and that Mustafa seemed open to this idea. Suleiman became angry, believing Mustafa was planning to take the throne. The next summer, after returning from his campaign, Suleiman called Mustafa to his tent. When Mustafa entered, Suleiman's guards attacked him, and after a struggle, they killed him.

It is said that Cihangir, another of Suleiman's sons, died of sadness a few months after hearing about his half-brother Mustafa's death. The two remaining brothers, Selim and Bayezid, were given command in different parts of the empire. However, a few years later, a civil war broke out between them, with each brother supported by his own loyal forces. With the help of his father's army, Selim defeated Bayezid in Konya in 1559. Bayezid then sought safety with the Safavids in Persia, along with his four sons. After diplomatic talks, Suleiman demanded that the Safavid Shah either send Bayezid back or execute him. For a large amount of gold, the Shah allowed a Turkish executioner to kill Bayezid and his four sons in 1561. This cleared the way for Selim to become sultan five years later.

Death of Suleiman

On September 6, 1566, Suleiman passed away during a military expedition to Hungary. He was 71 years old. His death happened just before an Ottoman victory at the Siege of Szigetvár. His Grand Vizier, Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, kept his death a secret during the army's retreat so that Selim II could become the new sultan without problems.

Suleiman's body was taken back to Istanbul for burial. However, his heart, liver, and some other organs were buried in Turbék, outside Szigetvár. A special building was built over this burial site, which became a holy place and a site for pilgrimages. Later, a mosque and a Sufi center were built nearby, and the site was protected by soldiers.

Suleiman's Legacy

Suleiman's legacy began even before he died. During his reign, many writers praised him, creating an image of him as an ideal ruler. Later Ottoman writers used this image to advise future sultans to follow Suleiman's example. For a long time, Western historians believed that the Ottoman Empire declined after Suleiman's death. However, modern scholars now largely disagree with this idea, calling it an "untrue myth."

Suleiman's conquests brought many important Muslim cities (like Baghdad), many Balkan regions (reaching modern-day Croatia and Hungary), and most of North Africa under Ottoman control. His expansion into Europe gave the Ottoman Turks a strong role in European power. The threat of the Ottoman Empire under Suleiman was so great that Austria's ambassador, Busbecq, warned that Europe might soon be conquered.

Suleiman's legacy was not just in military power. A French traveler, Jean de Thévenot, wrote a century later about the "strong agricultural base of the country, the well being of the peasantry, the abundance of staple foods and the pre-eminence of organization in Suleiman's government."

Even thirty years after his death, the English playwright William Shakespeare mentioned "Sultan Solyman" as a great military leader in his play The Merchant of Venice.

Through his support for the arts, Suleiman oversaw a Golden Age in Ottoman culture. There were huge achievements in architecture, literature, art, and philosophy. Today, the skyline of the Bosphorus and many cities in modern Turkey still feature the amazing buildings of Mimar Sinan. One of these, the Süleymaniye Mosque, is Suleiman's final resting place. He is buried in a domed tomb attached to the mosque.

It's important to remember that Suleiman's achievements were not just his own. Many talented people served him, such as his grand viziers Ibrahim Pasha and Rüstem Pasha, the chief legal official Ebussuud Efendi (who helped with legal reforms), and the chronicler Celalzade Mustafa (who helped expand the government and shape Suleiman's image).

Suleiman is honored with a marble portrait in the House Chamber of the United States Capitol. He is one of 23 historical figures recognized for their contributions to the principles of American law.

See also

In Spanish: Solimán el Magnífico para niños

In Spanish: Solimán el Magnífico para niños

- List of revolts during Suleiman's reign

- Muhteşem Yüzyıl