Andrei Sakharov facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Andrei Sakharov

|

|

|---|---|

| Андрей Сахаров | |

Sakharov at a conference of the USSR Academy of Sciences on 1 March 1989

|

|

| Born | 21 May 1921 |

| Died | 14 December 1989 (aged 68) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union

|

| Resting place | Vostryakovskoye Cemetery |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Nuclear physics, physical cosmology |

| Thesis | Теория ядерных переходов типа 0→0 (1947) |

| Doctoral advisor | Igor Tamm |

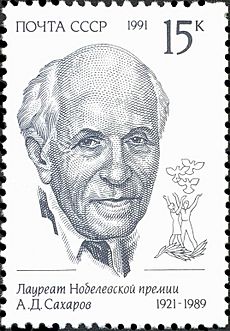

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov (Russian: Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров; 21 May 1921 – 14 December 1989) was a famous Soviet nuclear physicist. He was also a dissident, meaning he spoke out against the government. Sakharov won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work. He was a strong supporter of nuclear disarmament, peace, and human rights.

Sakharov became well-known for designing the Soviet Union's RDS-37. This was a secret name for the Soviet Union's thermonuclear weapons (hydrogen bombs). Later, Sakharov became a champion for civil liberties and reforms in the Soviet Union. Because of this, the government treated him badly. His efforts earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975. The Sakharov Prize is named after him. It is given every year by the European Parliament to people and groups who work for human rights and freedoms.

Biography

Early Life and Education

Andrei Sakharov was born in Moscow, Russia, on May 21, 1921. His father, Dmitri Ivanovich Sakharov, was a physics professor and a talented pianist. Andrei's grandfather, Ivan, was a respected lawyer. He believed in social fairness and human rights, even arguing against the death penalty. These ideas later influenced Andrei.

Andrei's mother was Yekaterina Alekseevna Sofiano. His parents and grandmother helped shape his personality. While his mother and grandmother were religious, his father was not. Andrei realized he didn't believe in God around age thirteen. However, he did believe in a "guiding principle" that was beyond physical laws.

Sakharov started studying physics at Moscow State University in 1938. During World War II, he had to move because of the war. He graduated in 1941 in Aşgabat, which is now in Turkmenistan. After graduating, he worked in a laboratory in Ulyanovsk. In 1943, he married Klavdia Alekseyevna Vikhireva. They had two daughters and a son. Klavdia passed away in 1969. In 1945, Sakharov returned to Moscow. He studied at the FIAN, part of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. He earned his Ph.D. in 1947.

Developing Nuclear Weapons

After World War II, Sakharov studied cosmic rays. In 1948, he joined the Soviet atomic bomb project. He worked with famous scientists like Igor Kurchatov and Igor Tamm. Sakharov's team came up with a new idea for a bomb in 1948. They suggested adding a layer of natural uranium around the deuterium (a type of hydrogen). This would make the bomb more powerful. This idea of a layered bomb was called the sloika, or "layered cake."

The first Soviet atomic bomb was tested on August 29, 1949. In 1950, Sakharov moved to Sarov. There, he played a key role in creating the first Soviet hydrogen bomb. This bomb used a design known in Russia as Sakharov's Third Idea. In the United States, a similar design was called the Teller–Ulam design.

Sakharov's idea was first tested as RDS-37 in 1955. He also worked on an even bigger version of this design. This was the 50-megaton Tsar Bomba, detonated in October 1961. It was the most powerful nuclear device ever exploded.

Sakharov felt his situation was similar to that of J. Robert Oppenheimer and Edward Teller in the US. He believed both deserved respect. They each thought they were right and had to follow their beliefs. Sakharov disagreed with Teller about nuclear testing in the atmosphere. However, he understood why Teller pushed for the H-bomb for the US. Sakharov never felt that creating nuclear weapons was a "sin," as Oppenheimer once said.

Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy

In 1950, Sakharov suggested an idea for a controlled nuclear fusion reactor. This was called the tokamak. Today, the tokamak design is still used for most research in this area. Sakharov and Tamm proposed using magnetic fields to hold very hot plasma inside a donut-shaped (torus) device. This would help control thermonuclear fusion reactions.

Magneto-Implosive Generators

In 1951, Sakharov invented and tested the first explosively pumped flux compression generators. These devices use explosives to squeeze magnetic fields. He called them MK (for MagnetoKumulative) generators. The MK-1 created a strong pulsed magnetic field. The MK-2, built in 1953, generated a huge electric current.

Sakharov also tested a "plasma cannon" using these generators. It could make a small aluminum ring turn into a stable, self-contained toroidal plasmoid and speed it up to 100 kilometers per second.

Particle Physics and Cosmology

After 1965, Sakharov went back to studying fundamental science. He began working on particle physics and physical cosmology.

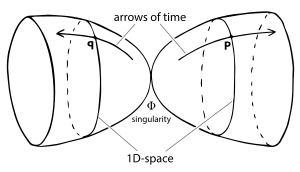

He tried to explain why there is more matter than antimatter in the universe. This is called baryon asymmetry. He was the first to suggest a reason for proton decay. Proton decay means that protons, which are usually stable, might eventually break down. Sakharov also thought about events happening before the Big Bang. His ideas led to the famous Sakharov conditions. These conditions describe what is needed for the universe to have more matter than antimatter.

Sakharov also wondered why the universe's curve is so small. This led him to think about cyclic models of the universe. In these models, the universe expands and contracts over and over. He also explored the idea of a "reversal of the time arrow." This means that time might flow differently before the Big Bang. Sakharov also suggested the idea of induced gravity. This was an alternative theory for how quantum gravity works.

Becoming an Activist

By the late 1950s, Sakharov started to worry about the moral and political effects of his work. He became politically active in the 1960s. Sakharov was against nuclear proliferation, which is when more countries get nuclear weapons. He pushed for an end to nuclear tests in the atmosphere. He played a role in the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, signed in Moscow.

In 1964, Sakharov spoke out against Nikolai Nuzhdin becoming a full member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Nuzhdin supported Lysenkoism, a discredited anti-genetics campaign. Sakharov publicly blamed Nuzhdin for harming many real scientists. Nuzhdin was not elected. This event made the government, led by Nikita Khrushchev, start gathering negative information about Sakharov.

A big change in Sakharov's political views happened in 1967. Anti-ballistic missile (ABM) defense became a major issue between the US and the Soviet Union. Sakharov wrote a secret letter to Soviet leaders on July 21, 1967. He explained that both countries should agree to stop developing ABM defenses. He warned that an arms race in this new technology would make nuclear war more likely. He also asked to publish his ideas in a newspaper. The government ignored his letter and would not let him discuss ABMs publicly.

After the Six-Day War in 1967, Sakharov actively supported Israel. He also kept in touch with refuseniks, who were people denied permission to leave the Soviet Union.

In May 1968, Sakharov finished an essay called "Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom." In it, he said that anti-ballistic missile defense was a huge threat to world nuclear war. This essay was secretly passed around in the Soviet Union (called samizdat). It was then published outside the country. Because of this, Sakharov was banned from doing any military research. He returned to FIAN to study basic theoretical physics.

For 12 years, Sakharov became a well-known and open dissident in Moscow. He stood outside courtrooms to support those on trial. He wrote appeals for over 200 prisoners. He also kept writing essays about the need for democracy.

In 1970, Sakharov helped start the Committee on Human Rights in the USSR. This group wrote appeals and gathered signatures for petitions. They also connected with international human rights groups. The KGB (Soviet secret police) watched their work closely. This put more pressure on Sakharov from the government.

Sakharov married Yelena Bonner, another human rights activist, in 1972.

By 1973, Sakharov often met with Western reporters. He held press conferences in his apartment. He asked the US Congress to pass the 1974 Jackson-Vanik Amendment. This law linked trade with the Soviet Union to whether they allowed people to leave the country more freely.

Attacked by the Soviet Government

Starting in 1972, Sakharov faced constant pressure from other scientists and the Soviet press. The famous writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn spoke up to defend him. In 1973 and 1974, the Soviet media kept attacking Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn. They were criticized for having pro-Western, anti-socialist views.

Sakharov later said it took him "years" to understand how much "deceit" there was in Soviet ideals. At first, he thought the Soviet State was a step into the future. But then he came to believe that "all governments and regimes... are bad, all peoples are oppressed."

Sakharov's ideas led him to believe that human rights should be the basis of all politics. He said that "what is not prohibited is allowed" should be taken literally. He challenged the unwritten rules the Communist Party put on society, even though the Soviet Constitution (1936) was supposed to be democratic.

From exile, he wrote to a fellow physicist. He said, "Fortunately, the future is unpredictable and also – because of quantum effects – uncertain." For Sakharov, this uncertainty meant he had a personal duty to shape the future.

Nobel Peace Prize (1975)

In 1973, Sakharov was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1974, he received the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca.

Sakharov was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975. The Norwegian Nobel Committee called him "a spokesman for the conscience of mankind." They said Sakharov showed that human rights are the only strong basis for true international cooperation.

Sakharov was not allowed to leave the Soviet Union to get his prize. His wife, Yelena Bonner, read his speech at the ceremony in Oslo, Norway. On the day the prize was given, Sakharov was in Vilnius. He was there for the trial of human rights activist Sergei Kovalev. In his Nobel speech, Sakharov called for an end to the arms race. He also asked for more respect for the environment, international cooperation, and human rights for everyone. He listed prisoners of conscience and political prisoners in the Soviet Union. He said he shared the prize with them.

By 1976, the head of the KGB, Yuri Andropov, called Sakharov "Domestic Enemy Number One."

Internal Exile (1980–1986)

Sakharov was arrested on January 22, 1980. This happened after he publicly protested against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. He was sent to the city of Gorky, which is now Nizhny Novgorod. This city was closed to foreigners.

From 1980 to 1986, Soviet police watched Sakharov closely. In his writings, he said his apartment in Gorky was searched and robbed many times. In 1980, the American Humanist Association named Sakharov the Humanist of the Year.

In May 1984, Sakharov's wife, Yelena Bonner, was arrested. Sakharov then started a hunger strike. He demanded that his wife be allowed to travel to the United States for heart surgery. He was forced into a hospital and force-fed. He was kept alone for four months. In August 1984, a court sentenced Bonner to five years of exile in Gorky.

In April 1985, Sakharov began another hunger strike for his wife's medical treatment abroad. Again, he was taken to a hospital and force-fed. In August, Soviet leaders discussed what to do about Sakharov. He stayed in the hospital until October 1985. Then, his wife was finally allowed to travel to the United States. She had heart surgery and returned to Gorky in June 1986.

In December 1985, the European Parliament created the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought. This prize is given every year for great work in human rights.

On December 19, 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev called Sakharov. Gorbachev had started new policies called perestroika and glasnost. He told Sakharov and his wife that they could return to Moscow.

Political Leader

In 1988, Sakharov received the International Humanist Award. He helped start the first independent political groups in the Soviet Union. He became a leading figure in the growing opposition to the government. In March 1989, Sakharov was elected to the new parliament. This was the All-Union Congress of People's Deputies. He helped lead the democratic opposition group. In November, the head of the KGB reported to Gorbachev that Sakharov was supporting a coal miners' strike.

In December 1988, Sakharov visited Armenia and Azerbaijan. He was on a mission to learn about the conflict there. He concluded that for Azerbaijan, the issue of Karabakh was about pride. But for the Armenians living in Karabakh, it was a matter of life and death.

Death

Soon after 9 p.m. on December 14, 1989, Sakharov went to his study to rest. He was preparing an important speech for the next day. His wife went to wake him at 11 p.m. as he had asked. She found Sakharov dead on the floor. It is believed he died from a heart arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat). This was likely caused by a heart condition called dilated cardiomyopathy. He was 68 years old. He was buried in the Vostryakovskoye Cemetery in Moscow.

Influence

Memorial Prizes

The Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought was created in 1988. The European Parliament established it in his honor. It is the highest award for human rights efforts given by the European Union. It is awarded every year to people who, like Sakharov, work peacefully for human rights.

The Andrei Sakharov prize is also given by the American Physical Society. It is awarded every two years since 2006. It recognizes scientists who show great leadership and achievements in supporting human rights.

The Andrei Sakharov Prize for Writer's Civic Courage was created in October 1990.

In 2004, an annual Sakharov Prize for journalism was started in Russia. Yelena Bonner approved this prize. It is funded by Pyotr Vins, a former Soviet dissident. The prize is given for "journalism as an act of conscience." Famous journalists like Anna Politkovskaya have won it.

Andrei Sakharov Archives and Human Rights Center

The Andrei Sakharov Archives and Human Rights Center was started in 1993. It is now located at Harvard University. Documents from this archive were published in 2005. These documents are available online. Most of them are letters from the head of the KGB to the Central Committee. They discuss the activities of Soviet dissidents and how newspapers should report on them. These documents show Sakharov's work, other dissidents' activities, and the actions of top Soviet officials and the KGB.

Legacy and Remembrance

Places Named After Him

- In Moscow, there is Academician Sakharov Avenue and the Sakharov Center.

- In the 1980s, a street in Washington, D.C., in front of the Soviet embassy, was renamed "Andrei Sakharov Plaza." This was a protest against his arrest in 1980.

- In Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, Sakharov Square is named after him.

- The Sakharov Gardens (started 1990) are at the entrance to Jerusalem, Israel. There is also a street named after him in Haifa.

- In Nizhny Novgorod, there is a Sakharov Museum]. It is in the apartment where the Sakharov family lived for seven years. A monument to him was built near the house in 2014.

- In Saint Petersburg, his monument stands in Sakharov Square. There is also a Sakharov Park.

- In 1979, an asteroid, 1979 Sakharov, was named after him.

- A public square in Vilnius, Lithuania, in front of the Press House, is named after Sakharov.

- Andreja Saharova iela in Riga, Latvia, is named after Sakharov.

- Andreij-Sacharow-Platz in downtown Nuremberg, Germany, is named in his honor.

- In Belarus, International Sakharov Environmental University was named after him.

- An intersection in Studio City, Los Angeles, is named Andrei Sakharov Square.

- In Arnhem, Netherlands, the bridge over the Nederrijn is called the Andrej Sacharovbrug.

- The Andrej Sacharovweg is a street in Assen, Netherlands. Other Dutch cities like Amsterdam and Utrecht also have streets named after him.

- There is a street in Copenhagen, Denmark, named after him.

- Quai Andreï Sakharov in Tournai, Belgium, is named in his honor.

- In Poland, streets in Warsaw, Łódź, and Kraków are named after him.

- Andreï Sakharov Boulevard in Sofia, Bulgaria, is named after him.

- In New York, a street sign at Third Avenue and 67th Street reads Sakharov-Bonner Corner. This honors Sakharov and his wife, Yelena Bonner. This corner was often used for anti-Soviet protests.

- In Chisinau, Moldova, there is Academician Andrei Sakharov street.

Media

- In the 1984 TV movie Sakharov, Jason Robards played him.

- In the TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation, one of the Enterprise-D's Shuttlecraft is named after Sakharov. This follows the tradition of naming shuttlecraft after famous scientists.

- The spaceship Cosmonaut Alexei Leonov in the novel 2010: Odyssey Two by Arthur C. Clarke uses a "Sakharov drive." The book was published in 1982, when Sakharov was in exile. It was dedicated to both Sakharov and Alexei Leonov.

- Russian singer Alexander Gradsky wrote a song called "In memory of Andrei Sakharov."

- In the PC game S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl, a scientist character is named Professor Sakharov.

Honours and Awards

- Hero of Socialist Labour (three times: 1953, 1956, 1962).

- Four Orders of Lenin.

- Lenin Prize (1956).

- Stalin Prize (1953).

- Elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1969).

- Elected member of the National Academy of Sciences (1973).

In 1980, Sakharov lost all his Soviet awards. This was for his "anti-Soviet activities." Later, during glasnost, he refused to have his awards returned. So, Mikhail Gorbachev did not sign the order to give them back.

- Prix mondial Cino Del Duca (1974).

- Nobel Peace Prize (1975).

- Elected member of the American Philosophical Society (1978).

- Laurea Honoris Causa (honorary degree) from the Sapienza University of Rome (1980).

- Grand Cross of Order of the Cross of Vytis (given after his death on January 8, 2003).

See Also

In Spanish: Andréi Sájarov para niños

In Spanish: Andréi Sájarov para niños

- Sakharov conditions

- Sakharov Prize

- List of peace activists

- Natan Sharansky

- Stanislaw Ulam

- Omid Kokabee

- Mordechai Vanunu

Images for kids