Carlism facts for kids

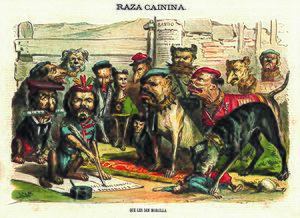

Carlism

Carlism is a political movement in Spain. It wanted a different branch of the Bourbon royal family to rule Spain. This branch came from Don Carlos (1788–1855).

The movement started in the early 1800s because of a disagreement over who should be the next king or queen of Spain. Many people were also unhappy with the main Bourbon line. Carlism became a big part of Spanish conservatism, fighting against new liberal ideas. This often led to wars, known as the Carlist Wars.

Carlism was strongest in the 1830s. It became important again after Spain lost its last major overseas lands like the Philippines, Cuba, Guam, and Puerto Rico to the United States in 1898.

Carlism played a role in the Spanish Civil War in the 1900s. After the war, it was part of the government under Francisco Franco. When Spain became a democracy again in 1975, Carlism became a very small political group.

Carlism is a political movement. It began with a royal flag that said it was "legitimate." It started when King Ferdinand VII died in 1833. It had strong support from many people. Carlism has three main ideas:

a) A royal flag: showing its claim to the throne.

b) A long history: linked to the different regions of Spain.

c) A political belief: traditionalism.

How Carlism Started

The Royal Family Problem

Rules for Who Becomes King or Queen

For a long time, most Spanish kingdoms allowed daughters to inherit the throne if there were no sons. This was called male-preference primogeniture. However, the kingdom of Aragon sometimes preferred a system where women could only inherit if all male relatives died out.

In 1700, a French prince, Philip V, became King of Spain. In France, a rule called Salic law meant women could not inherit the throne. So, Spain adopted a similar rule. This new rule meant women could not become queen unless all male descendants of Philip V died out. This change might have been pushed by other countries. They worried about France and Spain becoming too powerful if their royal families united.

The Spanish government tried to go back to the old rules several times. For example, Charles IV of Spain tried in 1789. But the issue became urgent in 1830. King Ferdinand VII was sick and had no children, but his wife was pregnant. He decided to bring back the 1789 law. This meant his unborn child would inherit the crown, even if it was a girl. This placed his daughter, Princess Isabel, ahead of his brother, Infante Carlos. Until then, Infante Carlos was next in line for the throne.

Many people, including the King's brother, thought this change was against the law. They formed the Carlist party. They believed the semi-Salic law was the correct one. This law would have made Infante Carlos king instead of Ferdinand's daughter, Isabella II.

Important Dates

- 13 May 1713: Philip V and the Spanish parliament (Cortes) changed the rules for who inherits the crown. They switched to a semi-Salic law. This meant women could only become queen if all male descendants of Philip V died out.

- 1789: During the rule of Charles IV, the Cortes agreed to go back to the old rules. But the law was not officially announced. This was partly because other Bourbon family branches protested. They felt it would reduce their rights to the throne.

- 1812: A new Spanish constitution set out rules for succession based on the older system.

- 31 March 1830: Ferdinand VII announced the 1789 law. This brought back the old rules for who inherits the throne.

- 10 October 1830: Isabella II was born to Ferdinand VII. After some disagreements, the new law was approved in 1832. Ferdinand's brother, Infante Don Carlos, felt his rights were taken away. He left for Portugal.

- 1833–1876: The Carlist Wars began.

Spain After King Ferdinand VII Died (1833)

After Napoleon's army occupied Spain, the country's leaders were divided. Some were "absolutists" who wanted to keep the old system. Others were "Liberals" who liked the ideas of the French Revolution.

The long war against Napoleon left many experienced guerrilla fighters. It also left many military officers who were mostly Liberals. The success of the 1808 uprising against Napoleon made many believe in the right to rebel. This had a lasting effect on Spanish politics for many years.

The rule of King Ferdinand VII could not fix the political divisions. The "Liberal Triennium" (1820–1823) brought back the 1812 constitution after a military uprising. But this was followed by the "Ominous Decade" (1823–1833). These were ten years of the king's absolute rule, which left bad memories of persecution for both sides.

Both groups had moderate and radical parts. The radical absolutists, called Apostólicos, saw Don Carlos as their leader. He was very religious and strongly against liberal ideas.

In 1827, Catalonia had a rebellion by the Agreujats ("the Aggrieved"). This was an ultra-absolutist movement that controlled large parts of the region for a while. Don Carlos was hailed as king for the first time, but he said he was not involved.

The last years of King Ferdinand's rule saw political changes because of the problems with his succession. In October 1832, the King formed a moderate government. This government almost stopped the Apostolic party. It also tried to get liberal support for Isabella's right to rule under her mother, Maria Christina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, as regent. The Liberals accepted Princess Isabella to get rid of Don Carlos.

Also, the early 1830s were affected by the end of Bourbon rule in France. There was also a civil war in Portugal between those who supported the legitimate king and those who supported liberal ideas.

Social and Economic Reasons

Before the Carlist wars, Spain faced a deep economic crisis. This was partly due to losing its lands in America and the government going bankrupt. The bankruptcy led to higher taxes, which made people even more unhappy.

Some economic plans by the Liberals, like the Desamortización, threatened many small farms. This plan involved taking over and selling common lands and Church property. Farmers relied on these common lands to feed their animals for free. This led to widespread poverty and the closure of many hospitals, schools, and charities.

Religion was another important issue. Radical Liberals became more and more against the Church. They were suspected of being involved with Freemasonry. This policy made many deeply Catholic Spanish people, especially in rural areas, turn against them.

The only institution abolished during the "Liberal Triennium" that King Ferdinand VII did not bring back was the Inquisition. One demand of the radical absolutist party was to bring it back. Liberals, when in power, pushed for central control and uniform administration.

Besides the Basque Country, many regions in Spain had strong local feelings. These feelings were hurt by the Liberals' centralizing policies. This anti-uniform localism, especially the defense of the fueros, became a key part of Carlism. This helped Carlism gain support in the Basque territories (Navarre, Gipuzkoa, Biscay and Araba). It also gained support in the old kingdoms of the Crown of Aragon (Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia). These areas disliked the loss of their old self-government rights due to the Nueva Planta Decrees.

History of Carlism

The history of Carlism can be divided into four main periods:

- 1833–1876: Carlists mainly tried to gain power through military actions.

- 1876–1936: Carlism became a peaceful political movement.

- 1936–1975: During the Spanish Civil War, Carlists joined Francisco Franco's side. Under Franco, some Carlists were in the government, but the movement slowly lost its power.

- 1975–present: After Franco's death, Carlism became much less important.

The Carlist Wars (1833–1876)

The period of the Carlist Wars was when the Carlists tried to take power by fighting. This time was important for Carlism. It shaped the movement's culture and beliefs for over a hundred years.

Key events from this time include:

- The First Carlist War (1833–1840): This was a civil war in Spain. It was fought over who should be the next ruler and what kind of monarchy Spain should have. Supporters of Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies, who was ruling for Isabella II of Spain, fought against supporters of Carlos de Borbón. Carlists wanted to bring back an absolute monarchy. Portugal, France, and the United Kingdom supported Maria Christina and sent troops to help.

- The Affair of the Spanish Marriages (1846): This involved secret plans between France, Spain, and the United Kingdom about the marriages of Queen Isabella II and her sister Luisa Fernanda.

- The Second Carlist War (1847–1849): This was a smaller uprising in Catalonia. The rebels tried to put Carlos VI on the throne. The war was supposedly to arrange a marriage between Isabella II and the Carlist claimant, Carlos de Borbón. But Isabella II married Francisco de Borbón instead.

- The 1860 expedition: The Count of Montemolín tried to take power through a military uprising. He landed in Sant Carles de la Ràpita, but was quickly captured. He was forced to give up his claim to the throne. This event almost ended Carlism. It was saved by his stepmother, Maria Theresa of Braganza.

- The "Glorious Revolution" (1868): Isabella II made many people unhappy and was forced out of Spain. Carlism, under its new leader Carlos VII, became a rallying point for many Catholics and conservatives. It became the main right-wing group against the new governments. After four years, Carlists tried fighting again in the:

- Third Carlist War (1872–1876).

Common Patterns in the Wars

All three wars followed a similar pattern:

- First, there was guerrilla fighting across Spain.

- Second, Carlists created areas of resistance with regular army units. The 1847 war did not go beyond this stage.

- Third, Carlists achieved stable control over some areas and set up their own government structures. No Carlist war went further than this.

At the start of each war, no regular army units were on the Carlist side. Only the third war was the result of a planned uprising.

The first war was very harsh on both sides. The Liberal army treated the local people badly, often suspecting them of supporting Carlists. Carlists often treated Liberals just as harshly. This led international powers to force both sides to follow some rules of war, like the "Lord Eliot Convention". But harshness did not disappear completely.

The areas where Carlism gained control during the first war were Navarre, Rioja, the rural Basque Country, inner Catalonia, and northern Valencia. These areas remained strongholds for Carlism throughout its history. Carlism had active supporters in other parts of Spain too. In Navarre, Asturias, and parts of the Basque Provinces, Carlism remained a significant political force until the late 1960s.

Carlist Military Leaders

Carlists in Peaceful Times (1868–1936)

When Isabella II lost power in 1868, and with strong support from Pope Pius IX, many former conservative Catholics joined the Carlist cause. For a while, Carlism became the most important right-wing opposition group. It had about 90 members in parliament in 1871.

After their defeat, a group led by Alejandro Pidal left Carlism. They formed a moderate Catholic party, which later joined with other conservatives.

In 1879, Cándido Nocedal was put in charge of reorganizing the party. He used a very aggressive press. Pope Leo XIII even published a letter in 1883 trying to calm things down. Nocedal insisted on sticking strictly to Carlist political and religious beliefs. This led to a very radical group, which was expelled in 1888. This group formed the small but influential Integrist Party.

Meanwhile, Marquis de Cerralbo built a modern mass party. It was based on local groups called "Círculos," which had social programs. Carlism actively opposed the political system of the time. They even joined large groups, like "Solidaritat Catalana" in 1907, with regionalists and republicans. Carlists had little success in elections, except in Navarre.

From 1893 to 1918, Juan Vázquez de Mella was their most important leader and thinker. He was supported by Víctor Pradera, who influenced many Spanish conservative thinkers.

World War I affected Carlism. The Carlist claimant, Jaime, Duke of Madrid, had ties to the Russian Imperial Family. He was also held under house arrest in Austria. He supported the Allies. When the war ended and Don Jaime could communicate freely, a crisis happened. Vázquez de Mella and others had to leave the party leadership.

In 1920, Carlism helped start the "Sindicatos Libres" (Catholic Labour Unions). This was to counter the growing influence of leftist unions. Carlism tried to balance workers' demands with the interests of the upper class, to whom they were connected.

Miguel Primo de Rivera's dictatorship (1923–1930) was opposed by Carlism, but they viewed it with mixed feelings. Like most parties, Carlism became less active. It only became active again with the start of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931. Before the Republic was announced, Carlists joined with the Basque Nationalist Party. They formed the Coalición Católico Fuerista in the main Carlist areas. This group supported the old local laws, called charters.

In October 1931, the Carlist claimant Duke Jaime died. He was succeeded by the 82-year-old Alfonso Carlos de Borbón. He brought together the integrists and the "Mellists." They believed in a Spanish nationalism based on regions and strongly linked Spain with Catholicism. The new Carlist party, Comunión Tradicionalista, chose to openly oppose the Republic. The Republic wanted a secular government, separating Church and state, and allowing freedom of religion. Traditionalists could not accept this.

The Comunión Tradicionalista (1932) was very Catholic and against secularism. They planned a military takeover. They believed in a final fight against forces they saw as anti-Christian.

In Navarre, the main Carlist area, the movement focused on the newspaper El Pensamiento Navarro. This paper was mostly read by clergy. The paramilitary group Requeté was reactivated. As early as May 1931, young Carlists organized arms smuggling. They distributed weapons among "defense" groups called Decurias. Wealthy people helped fund this. In 1932, the first attempt to overthrow the Republic happened, called the Sanjurjada, with Carlist support.

The October 1934 Revolution led to the death of Carlist deputy Marcelino Oreja Elósegui. Manuel Fal Condé then took over from young Carlists who wanted to overthrow the Republic. Carlists began preparing for an armed conflict with the Republic and its leftist groups. The Requeté grew from defensive groups in Navarre to a well-trained and strong paramilitary group. It had 30,000 "red berets" (8,000 in Navarre and 22,000 in Andalusia).

Spanish Civil War and Franco's Rule (1936–1975)

During the War (1936–1939)

The Carlist militia, the Requetés, had military training during the Second Spanish Republic. But they had different ideas from many of the generals planning the uprising. When the July 1936 revolt and the Spanish Civil War began, Carlists naturally joined the Nationalist rebels, though not always easily. General Mola was known for his tough methods. He had been moved to Pamplona by the Republican government, which was ironically the center of the far-right rebellion.

In May 1936, General Mola met with Ignacio Baleztena, a Carlist leader in Navarre. Baleztena offered 8,400 volunteers from the Requetés to support the uprising. There were big differences between Manuel Fal Conde (Carlist) and Mola (a Falangist). This almost broke the agreement for Carlist support on July 4, 1936. However, Tomás Domínguez Arévalo helped restore their cooperation against the Republican government.

The highest Carlist leader, Duke Alfonso Carlos, did not approve the agreement. But Mola was already negotiating directly with the Carlist Navarre Council. This council decided to support the uprising. On July 19, war was declared in Pamplona. The Carlist troops in the city took control. In a few days, almost all of Navarre was taken by the military and the Requetés. There was no battle front there.

Immediately, the rebels, with the help of the Requetés and the clergy, began harsh actions to stop any opposition. This affected many people who were progressive or Basque nationalists. Many people were killed without trial, with numbers ranging from 2,857 to 4,000. Those who survived faced social humiliation and control.

Carlists did not do well in Gipuzkoa and Biscay. The military uprising failed there. Carlist units were overcome by forces loyal to the Republic, including leftist groups and Basque nationalists. Many Carlists crossed the front line to safety in the rebel zone. They joined Carlist regiments in Álava and Navarre. Pamplona became the starting point for the War in the North.

On December 8, 1936, Fal Conde had to leave for Portugal after a major disagreement with Franco. On April 19, 1937, the Carlist political group was forced to join with the Falange. This created a pro-Franco nationalist party called Falange Española Tradicionalista de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista or FET de las JONS. The new Carlist claimant, Javier, prince de Borbón-Parma, was unhappy with the merger. He condemned Carlists who joined the new party.

He was expelled from the country. Fal Conde was not allowed to return to Spain until after the war. Most lower-level Carlists, except those in Navarre, generally stayed away from the new party. Many never joined at all.

Franco's Spain

After this, the main Carlists held an uneasy minority position within Franco's government. They often disagreed with official policies. However, the justice ministry was given three times to a loyal "Carlist." This person was then expelled from the Traditionalist Communion. This time was also marked by problems with who would succeed Franco and internal disagreements about Franco's rule.

Carlist ministers in Franco's August 1939 government included General José Enrique Varela (army) and Esteban Bilbao (justice). Also, two of nine seats in the Junta Política were given to Carlists. Seven Carlists held seats on the hundred-member National Council of the FET.

Carlists continued to clash with Falangists. A notable incident happened at Bilbao's Basilica of Begoña on August 16, 1942. During a Carlist rally, two grenades were thrown by Falangists. The incident led to changes in Franco's government. Six Falangists were found guilty, and one was executed.

In 1955, Fal Conde resigned as leader of the movement. He was replaced by José María Valiente. This change marked a shift from opposing Franco to working with him. This cooperation ended in 1968 when Valiente left office.

Franco recognized royal titles from both the Carlist and the main Bourbon branches. When Franco died, the movement was deeply divided. It could not gain much public attention again.

In 1971, Don Carlos Hugo, prince de Borbón-Parma founded the new Carlist Party. This party focused on a confederal vision for Spain and socialist self-management. At Montejurra, on May 9, 1976, supporters of the old and new Carlism fought. Two of Hugo's supporters were killed by far-right militants. The Carlist Party accused Hugo's younger brother, Don Sixto Enrique de Borbón-Parma, of helping the militants. The Traditionalist Communion denies this.

After Franco (1975–Present)

In the first democratic elections on June 15, 1977, only one Carlist senator was elected. This was Fidel Carazo from Soria, who ran as an independent. In the 1979 elections, right-wing Carlists joined a far-right group called Unión Nacional. This group won a seat in parliament for Madrid, but the elected person was not a Carlist. Since then, Carlists have not been in parliament. They have only won seats on town councils.

In 2002, Carlos Hugo gave the family's historical papers to the Archivo Histórico Nacional. His brother Don Sixto Enrique and all Carlist groups protested this.

Today, three political groups claim to be Carlist:

- Comunión Tradicionalista (led by José Miguel Gambra Gutiérrez)

- Comunión Tradicionalista Carlista (led by Telmo Aldaz de la Quadra-Salcedo)

- Partido Carlista (led by Jesús María Aragón Samanes)

Carlist Claimants to the Throne

The numbers used for the kings are those used by their supporters. Even though they were not officially crowned kings, they used some titles linked to the Spanish throne.

| Claimant | Portrait | Birth | Marriages | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carlos, Count of Molina (Carlos V) (English: Charles V) 1833–1845 |

|

29 March 1788, Aranjuez son of Carlos IV and Maria Luisa of Parma |

Maria Francisca of Portugal September 1816 3 children Maria Teresa, Princess of Beira 1838 No children |

10 March 1855 Trieste aged 66 |

| Carlos, Count of Montemolin (Carlos VI) (English: Charles VI) 1845–1861 |

|

31 January 1818, Madrid son of Carlos, Count of Molina and Maria Francisca of Portugal |

Maria Carolina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies 10 July 1850 No children |

31 January 1861 Trieste aged 43 |

| Juan, Count of Montizón (Juan III) (English: John III) 1860–1868 |

|

15 May 1822, Aranjuez son of Carlos, Count of Molina and Maria Francisca of Portugal |

Beatrix of Austria-Este 6 February 1847 2 children Ellen Sarah Carter ? 2 children |

21 November 1887 Hove aged 65 |

| Carlos, Duke of Madrid (Carlos VII) (English: Charles VII) 1868–1909 |

|

30 March 1848, Ljubljana son of Juan, Count of Montizón and Beatrix of Austria-Este |

Margarita of Bourbon-Parma 4 February 1867 5 children Berthe de Rohan 28 April 1894 No children |

18 July 1909 Varese aged 61 |

| Jaime, Duke of Madrid (Jaime III) (English: James III) 1909–1931 |

|

27 June 1870, Vevey son of Carlos, Duke of Madrid and Margarita of Bourbon-Parma |

never married | 2 October 1931 Paris aged 61 |

| Alfonso Carlos, Duke of San Jaime (Alfonso Carlos I) (English: Alphonse Charles I) 1931–1936 |

|

12 September 1849 London son of Juan, Count of Montizón and Beatrix of Austria-Este |

Maria das Neves of Portugal 26 April 1871 1 child |

29 September 1936 Vienna aged 87 |

Who Came After Alfonso Carlos?

When Alfonso Carlos died in 1936, most Carlists supported Prince Xavier of Bourbon-Parma. Alfonso Carlos had named him as the leader of the Carlist Communion.

A small number of Carlists supported Archduke Karl Pius of Austria, Prince of Tuscany. He was a grandson of Carlos VII through a female line.

A very small group of Carlists supported Alfonso XIII. He was the exiled king of Spain. Most Carlists, however, believed Alfonso was not eligible. They thought his ancestors had acted against the king. Also, many believed his family line was not legitimate.

Most of the following events happened under the rule of Francisco Franco. He cleverly played different groups against each other.

Borbón-Parma Claim

- Francisco Javier I

Prince Xavier of Bourbon-Parma (1889–1977), known as Don Javier de Borbón, was named leader by Alfonso Carlos in 1936. He was the closest Bourbon family member who shared Carlist ideas.

During World War II, Prince Xavier served in the Belgian army. He later joined the French resistance. The Nazis captured him and sent him to concentration camps. American troops freed him in 1945. In 1952, Javier was declared King of Spain. He claimed this based on Carlist rules. After Alfonso Carlos died, a successor had to be found. This meant tracing the male line of Philip V to the oldest descendant not excluded by law. In 1952, Don Javier was seen as the rightful claimant. He was raised as a Carlist and named regent in 1936. His claim as king was seen as a result of royal legitimacy, not just politics. He remained the Carlist claimant until he gave up his claim in 1975.

Changes in the Carlist movement divided Javier's supporters. This happened between his two sons, Carlos Hugo and Sixto Enrique, in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Carlos Hugo changed Carlism into a socialist movement. His brother Sixto Enrique, supported by his mother, followed a far-right path.

In 1977, Sixto Enrique's supporters published a statement from Javier condemning Carlos Hugo. A few days later, Carlos Hugo's supporters published a statement from Javier recognizing Carlos Hugo as his heir.

- Carlos Hugo I

Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma (1930–2010) was Xavier's older son. He was the Carlist claimant from 1977 until his death. After trying to get close to Franco (1965–1967), Carlos Hugo changed to a leftist, socialist movement. In 1979, he accepted Spanish citizenship from King Juan Carlos I. In 1980, he left the Carlist Party, which he had created. Carlos Hugo had the support of a minority of Carlists. He also excluded the Luxembourg branch of the family from Carlist succession. This was because of unequal marriages by princes of that branch.

- Carlos Javier I

Prince Carlos, Duke of Parma (born 1970) is Carlos Hugo's older son. He inherited the Carlist claim when his father died in 2010. Carlos has the support of a minority of Carlists, including the Carlist Party.

- Sixto Enrique

Prince Sixto Enrique of Bourbon-Parma (born 1940) claims to be the current leader of the Carlist Communion. He is known as the Duke of Aranjuez.

Sixto Enrique is supported by the minority Comunión Tradicionalista. Some others believe his older brother Carlos Hugo was the rightful heir but was not eligible because of his socialist views. Sixto Enrique has never claimed to be Carlist king. He hopes one of his nephews will one day accept traditional Carlist values.

Habsburgo-Borbón Claim

The oldest daughter of Carlos, Duke of Madrid was Bianca de Borbón y Borbón-Parma (1868–1949). She married Archduke Leopold Salvator of Austria. In 1943, one of their sons claimed to be the Carlist claimant. This claim came through a female line, so most Carlists rejected it.

- Archduke Karl Pius of Austria, Prince of Tuscany was a Carlist claimant from 1943 to 1953. Some of General Franco's officials supported him. Since he used the title "King Carlos VIII," the movement that supports this family branch is called Carloctavismo.

- Archduke Anton of Austria was Karl Pius's brother. He was Carlist claimant (Carlos IX) from 1953 to 1961.

- Archduke Franz Josef of Austria was the brother of Karl Pius and Anton. He was Carlist claimant (Francisco I) from 1961 to 1975.

- Archduke Dominic of Austria is Anton's son. He has been Carlist claimant (Domingo I) since 1975.

In 2012, Senator Iñaki Anasagasti suggested creating a united Basque-Navarrese-Catalan monarchy with Archduke Dominic of Austria as its king.

Borbón Claim

- Alfonso de Borbón

Alfonso XIII became the senior male descendant of the House of Bourbon when Alfonso Carlos died in 1936. He had been the constitutional king of Spain until his exile in 1931. He was the son of King Alfonso XII. Alfonso XII was the son of Francisco de Asis de Borbón, who was the son of Infante Francisco de Paula. Francisco de Paula was the younger brother of Charles V. A small number of Carlists recognized Alfonso XIII as their claimant. They saw his death as a chance to unite Spanish monarchists. However, many Carlists considered Francisco de Paula and his descendants legally and morally excluded. They believed they had acted against the king, according to Spanish succession laws from 1833. In 1941, Alfonso gave up his claim; he died two months later.

Alfonso's oldest son had died in 1938. His second son Infante Jaime, Duke of Segovia had been pressured to give up his rights to the constitutional succession in 1933. Both had married in a way that was not considered equal for royal succession. King Alfonso's third son, Don Juan, Count of Barcelona was his chosen successor.

- Juan de Borbón Claim

- Infante Don Juan, Count of Barcelona (1913–1993) was Alfonso XIII's third son. He was claimant to the Spanish throne from 1941 until he gave up his claim in 1977. In 1957, some Carlists recognized him as their leader.

- King Juan Carlos I is the surviving son of Don Juan. He was the King of Spain from 1975 until he stepped down in 2014.

- King Felipe VI is Juan Carlos I's only son. He is the current king of Spain since 2014, as confirmed by the Spanish Constitution of 1978.

- Jaime de Borbón Claim

- Infante Jaime, Duke of Segovia was Alfonso XIII's second son. He was the older brother of Juan. Even though he gave up his claim to the Spanish throne in 1933, Jaime announced in 1960 that he was the Carlist claimant. He sometimes used the title Duke of Madrid. He remained a claimant until his death in 1975. He had only a few Carlist supporters. Among them was Alicia de Borbón y de Borbón-Parma, the only surviving daughter of a previous Carlist claimant, Carlos, Duke of Madrid. Jaime also became the Legitimist claimant to the French throne.

- Alfonso, Duke of Anjou and Cádiz was Jaime's son. He did not claim the Carlist succession between 1975 and his death in 1989.

- Louis Alphonse, Duke of Anjou is Alfonso's son. He has never claimed the Carlist succession.

What Carlism Believes In

Carlism can be described as a movement that reacted against the ideas of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution of 1789. It was against ideas like separating church and state, individualism, equality for all, and rationalism. It is similar to French Reactionaries who wanted to go back to older ways.

It is hard to fully describe Carlist beliefs for a few reasons:

- Carlists were traditionalists. They did not trust new political ideas. They believed in a "historical constitution" based on history and Church teachings, not a "philosophical" one based on new ideas.

- Carlism has been active for over 170 years. It attracted many different kinds of people, making it hard to put into one category.

- There was almost never just one way of thinking within Carlism.

- Carlism shared some of its ideas with other political groups. For example, some conservative and Catholic groups in Spain were influenced by Carlism's ideas about fueros and regional self-government.

Carlism and Falangism had some things in common, like being socially conservative, Catholic, and against Communism. But they also had big differences. Falangism wanted a very strong central Spanish government. Carlism, however, supported the fueros, which meant preserving local culture and regional self-rule. This was one of their main beliefs.

Carlism also supported the Salic Law for royal succession, meaning they were legitimist monarchists.

God, Fatherland, Local Rule, King

These four words (Dios, Patria, Fueros, Rey) were the motto and core beliefs of Carlism:

- Dios (God): Carlism believed the Catholic Faith was central to Spain. They felt they must actively defend it in politics.

- Patria (Fatherland): Carlism was very patriotic. They saw the Fatherland as a collection of communities (local, regional, and Spain as a whole) united.

- Fueros (local laws/charters): This meant limiting the king's power by recognizing local and regional self-rule. It also included other community types, especially the Church. This idea came from Spain's history. It also matched the idea of subsidiarity in Catholic social thought. Some versions of the motto do not include "Fueros."

- Rey (King): Carlism rejected the idea of national sovereignty (where the people rule). They believed power belonged to the king. This king had to be legitimate by birth and by his actions. But his power was limited by the teachings of the Church and the laws and customs of the Kingdom. It was also limited by councils, traditional parliaments (Cortes), and independent groups. The King also had to protect the poor and uphold justice.

Supporters

Carlism was a true "mass movement." It had supporters from all social classes, with most being peasants and working-class people. Because of this, Carlism was involved in creating Catholic trade unions.

Other Groups and Influence

- Cultural and political regionalism in Spain (not to be confused with regional nationalism) largely came from Carlism. The ideas of Carlist thinker Juan Vázquez de Mella still influence this area today.

- One of the founders of Basque nationalism, Sabino Arana, came from a Carlist background. For many years, he tried to gain support from the same group: deeply Catholic Basques. Basque nationalism was shaped by the Liberal Engracio de Aranzadi. Carlists and Nationalists wrote the first Basque Statute of Autonomy. But Carlists fought and defeated Basque nationalists in the 1936–1937.

- Fuerismo was a belief common in the Basque provinces. It supported the main monarchy but wanted to keep the local self-rule of the provinces.

- Catholic politics are very important for Carlism. They often used the slogan Christus Rex (Christ the King).

- Victor Pradera's ideas were very influential in Spanish authoritarian thinking in the 1930s and 1940s, through the group Acción Española.

- Fernando Sebastián Aguilar, Archbishop of Pamplona and Tudela, caused discussion in 2007. He publicly said that the Traditionalist Carlist Communion was worthy of consideration and electoral support.

Symbols

- Motto: God, Fatherland, Local Rule, King (Dios, Patria, Fueros, Rey)

- Flag: A red cross of Burgundy on a white background.

- The red beret. In Basque, Carlist soldiers were called txapelgorri. The red beret was worn by Carlist soldiers in the First Carlist War. It later became a symbol for Carlists in general, often with a yellow pom pom or tassel.

- Anthem: Oriamendi

Names and Terms

The term "carlistas" (Carlists) for followers of Carlos Maria Isidro appeared in the mid-1820s. After the First Carlist War began in 1833, the liberal press used the name often. Carlists themselves slowly started to accept the name in the 1840s. Over time, "Carlism" became a common term. From 1909 to 1931, the movement was often called "Jaimismo" or "Jaimistas." This was because the claimant, Don Jaime, did not have the name Carlos.

In the late 1800s, the term "tradicionalistas" (traditionalists) also became common. It was used for the movement in general or for some of its groups. However, "carlistas" was used much more often in the press until 1931. During the time of the Republic (1931–1936), "tradicionalistas" was used more often. In the Franco era (1939–1975), "carlistas" was slightly more common. Today, historians disagree on how "traditionalism" and "Carlism" relate to each other.

Until the late 1860s, the Carlist movement did not have a formal structure. Before the Third Carlist War, the first Carlist political group appeared. Over the next 160 years, the main movement was part of different political groups. These groups sometimes had different names. Carlists saw themselves as a broad social movement, not just a political party. This led to confusion in names. For example, in the early 1900s, many different names were used in the press for the Carlist party. In the mid-1930s, the claimant Alfonso Carlos tried to make one official name, "Comunión Tradicionalista Carlista." But he later used other names himself.

| period | CCM | CJ | CL | CT | CTC | PC | PCM | PJ | PT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1860–1879 | 242 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 6807 | 117 | 0 | 143 |

| 1880–1899 | 686 | 0 | 3 | 1449 | 0 | 9947 | 82 | 3 | 2348 |

| 1900–1919 | 210 | 227 | 183 | 1390 | 0 | 5260 | 21 | 1601 | 1958 |

| 1920–1939 | 210 | 24 | 44 | 2671 | 7 | 362 | 5 | 257 | 1114 |

| 1940–1959 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 179 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 16 |

| 1960–1979 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 954 | 68 | 3726 | 4 | 1 | 17 |

| total | 1355 | 251 | 235 | 6646 | 76 | 26109 | 231 | 1864 | 5686 |

Related Words

- Estella-Lizarra was where the Carlist court was located.

- Bergara/Vergara was the place of the Abrazo de Vergara. This event ended the First Carlist War in the North.

- Brigadas de Navarra were army units. They were mostly made up of Requeté forces from Navarre at the start of the Spanish Civil War. They fought a lot during the War.

- Detente bala ("Stop bullet!") was a small patch with an image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Most requetés wore it on their uniform over their heart.

- Margaritas. This was a Carlist women's organization. They often worked as war nurses.

- Ojalateros were people who said, Ojalá nos ataquen y ganemos ("Wish they would attack us and we won"). But they did nothing to help win. The name sounds like "tinkerer."

- Requetés were the armed Carlist militias.

- Trágala, an expression meaning to force ideas on opponents. It was also a Liberal fighting song.

See also

In Spanish: Carlismo para niños

In Spanish: Carlismo para niños

- Carloctavismo

- Historiography on Carlism during the Francoist era

- Integrism (Spain)

- Juan Vázquez de Mella

- Legitimist

- Loyalism

- Mellismo

- Miguelist

- Order of Prohibited Legitimacy

- Parties and factions in Isabelline Spain

- Reactionary

- Restoration (disambiguation)

- Royalism

- Traditionalism (Spain)

- War of succession

- List of movements that dispute the legitimacy of a reigning monarch