Esopus Creek facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Esopus Creek |

|

|---|---|

Anglers in the Esopus near Phoenicia, with Mount Tremper in the background, 2020

|

|

Map of Esopus Creek and its watershed

|

|

| Native name | Atkarkaton, Atkankarten |

| Other name(s) | Esopus Kill, Saugerties Creek |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| Region | Catskills, Hudson Valley |

| County | Ulster |

| Towns | Shandaken, Olive, Marbletown, Hurley, Ulster, Saugerties (also Phoenicia, Kingston and the village of Saugerties) |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Winnisook Lake Shandaken 2,660 ft (810 m) 42°0′55″N 74°24′45″W / 42.01528°N 74.41250°W |

| River mouth | Hudson River at Saugerties 1–4 ft (0.30–1.22 m) 42°4′17″N 73°55′45″W / 42.07139°N 73.92917°W |

| Length | 65.4 mi (105.3 km) |

| Discharge (location 2) |

|

| Basin features | |

| River system | Hudson River |

| Basin size | 425 sq mi (1,100 km2) |

| Tributaries |

|

| Waterfalls | Otter Falls, Parker Falls, Blossom Falls, Glenerie Falls, Cantine Falls |

The Esopus Creek is a 65.4-mile-long (105.3 km) river in New York State. It flows from the Catskill Mountains to the Hudson River. The creek starts at Winnisook Lake on Slide Mountain, which is the highest peak in the Catskills. It then flows through Ulster County and empties into the Hudson River at Saugerties.

Many smaller streams flow into the Esopus, making its watershed (the area of land that drains into the river) quite large. Part of the creek is blocked by a dam at Olive Bridge. This creates the Ashokan Reservoir, which is an important part of New York City's water supply system. Water from another reservoir, Schoharie Reservoir, is also sent into the Esopus through the Shandaken Tunnel.

The creek was originally called Atkarkaton or Atkankarten by the Native Americans. Dutch settlers later called it the "Esopus Kill". The name "Esopus" comes from the Esopus tribe of the Lenape people. They lived along the lower part of the creek when the Dutch first arrived in the 1600s. The wide valley of the Esopus Creek was a good trading route for the Lenape, who traded beaver furs with the Europeans.

Later, the Esopus area became important for logging, tanning, and making charcoal. These industries slowed down in the late 1800s. After that, the region became popular for resorts and outdoor activities, especially trout fishing. Today, the Esopus Creek is divided into two main parts by the Ashokan Reservoir. The upper part is a wild mountain stream, while the lower part is closer to the Hudson River and becomes more like an estuary (where fresh and saltwater mix).

The upper Esopus is known as one of the best trout streams in the Northeast. Many fly fishermen visit to catch trout. Canoeists and kayakers enjoy its whitewater. In the summer, tubing is also very popular. The lower Esopus is important for its natural beauty and environment. The estuary near Saugerties is a good spot for bass fishing.

Contents

- What's in a Name? The Esopus Creek's History

- The Creek's Journey: Upper and Lower Esopus

- The Esopus Watershed: A Natural Home

- A Look Back: History of Esopus Creek

- Fun on the Esopus: Recreation

- Caring for the Esopus: Conservation and Management

- Tributaries: Streams that Feed the Esopus

- Images for kids

What's in a Name? The Esopus Creek's History

Historians believe that the first Dutch settlers named the creek after the Lenape tribe who lived along its banks. The Lenape might have called it Atkarkarton or Atkankarten, which means "smooth land" in their language. This probably referred to a flat area near Kingston.

By the mid-1600s, the name Esopus was commonly used. It is thought to come from seepus, a word meaning "river" in the Delaware languages. Some people think Esopus means "little river" because of a small part of the name. Another idea is that it means "high banks," referring to how the river often floods.

The Creek's Journey: Upper and Lower Esopus

The Esopus Creek is often thought of as two different streams: the upper part and the lower part. The Ashokan Reservoir divides them.

The upper part of the creek is like a mountain stream. It is shallow, rocky, and flows quickly. This is where most people go to fish for trout. The upper part is also split into a "small" and "big" stream by the water coming from the Shandaken Tunnel.

Below the reservoir, the creek starts again. It becomes flatter, deeper, and flows slower until it reaches its short estuary near the Hudson River.

Small Upper Esopus: From Winnisook Lake to Big Indian

The Esopus Creek begins at Winnisook Lake. This lake is 2,660 feet (810 m) above sea level, making it the highest lake in the Catskills. It's located on the slopes of Slide Mountain in the town of Shandaken. The creek flows north from here, dropping quickly through its first few miles. This section is narrow and rocky. You can find three waterfalls here: Otter Falls, Parker Falls, and Blossom Falls.

As the creek flows, it forms part of the edge of the Big Indian Wilderness Area. It also meets other streams like Giant Ledge Stream and Hanging Birds Nest Brook. The valley starts to open up, and you'll see some cleared land. The Esopus then flows past the small area of Oliverea.

Big Upper Esopus: From Big Indian to the Reservoir

After flowing through Big Indian Hollow, the Esopus reaches the small community of Big Indian. Here, it turns east and flows alongside New York State Route 28 all the way to the Ashokan Reservoir. The valley becomes wider, with more open areas and forests.

The creek receives water from Birch Creek and other smaller streams. It then flows past the town of Shandaken. A very important point along the creek is the Shandaken Tunnel outlet, also known as the Portal. This tunnel brings extra water from the Schoharie Reservoir into the Esopus, making its flow much stronger.

South of the Portal, the Esopus turns southeast. It flows past Woodland Creek, its largest tributary from the right. Then it reaches Phoenicia, a larger town along its path. Here, Stony Clove Creek joins the Esopus from the north. The creek gets wider but stays shallow.

The Esopus continues south, passing Mount Tremper and Romer Mountain. It flows through Mount Pleasant and Mount Tremper. Finally, it enters the town of Olive and flows into the Ashokan Reservoir. This marks the end of the upper section of the creek.

Lower Esopus: From Ashokan Reservoir to Saugerties

The Esopus Creek flows out of the Ashokan Reservoir's spillway near Olive Bridge. As it leaves the reservoir, the creek drops in elevation. It flows through a wide, forested area. It then enters the town of Marbletown and leaves the Catskill Park.

In Marbletown, the creek flows through a narrow gorge before widening. It then flows south, passing farms and open fields. The Esopus reaches its southernmost point in Marbletown before turning northeast. It flows past Hurley and then reaches the city of Kingston, the largest town along the creek.

The creek continues past Kingston, flowing under the New York State Thruway. It receives water from Tannery Brook and the Saw Kill. The area along the river becomes more developed with homes and docks.

About a mile north of the Saw Kill, the Esopus flows over a small dam. It then reaches the town of Saugerties. Here, its last major tributary, Plattekill Creek, joins it. The creek then goes down Glenerie Falls, a series of five waterfalls.

Below Glenerie Falls, the Esopus flows north through a narrow valley. It passes the Esopus Bend Nature Preserve, which protects the land along the creek. Finally, the Esopus turns east, enters the village of Saugerties, and flows over Cantine Dam, creating Cantine Falls. After about 1.3 miles (2.1 km), the Esopus Creek empties into the Hudson River at Saugerties Light.

The Esopus Watershed: A Natural Home

The Esopus Creek's watershed covers 425 square miles (1,100 km2). Most of this area is in Ulster County, but parts also reach into Greene County and a small bit of Delaware County. The upper watershed, above the reservoir, is 256 square miles (660 km2), and the lower watershed is 169 square miles (440 km2).

The upper Esopus watershed is very rugged and almost entirely covered in forests (95 percent). Over half of this land is part of the "forever wild" Forest Preserve, which means it is protected from most logging or clearing. There are different types of forests, including spruce-fir trees on high mountain tops and beech-birch-maple trees on the slopes.

Downstream of the reservoir, the forests change. The flat areas along the river are a mix of silver maple and elm trees. There are also some rare pine and scrub oak areas. While there are some small towns along the creek, there isn't much farming in the upper watershed.

The Esopus watershed includes many mountains, with 21 peaks over 3,000 ft (910 m) high. This includes parts of 16 of the 35 Catskill High Peaks (mountains over 3,500 ft (1,100 m)). Slide Mountain, the highest peak in the Catskills, is also the highest point in the Esopus watershed.

Below the reservoir, the lower Esopus is also surrounded by forests at first. Further downstream, the flat areas become heavily farmed, with over 2,000 acres (810 ha) of farmland next to the creek.

A Look Back: History of Esopus Creek

The history of the Esopus Creek and its valley has several interesting periods.

Natural History: How the Creek Was Formed

The path of the upper Esopus Creek was shaped about 375 million years ago. At that time, the Catskills were a river delta with shallow channels leading to a large inland sea. A meteor hit the area, creating a 6 miles (9.7 km) wide impact crater. The walls of this crater match the paths of the upper Esopus and Woodland Creek today.

Over time, the crater filled with silt and became a lake. As the land rose, the stream began to form along weaker rock layers. This process created the deep and wide valley of the Esopus. About 12,000 years ago, the Wisconsin glaciation (a period when glaciers covered the land) filled the valley. The glaciers carved the slopes and left behind a lot of clay, which still makes the water cloudy during floods. When the glaciers melted, they also created glacial lakes, like the one that used to be at Shokan, which is now the Ashokan Reservoir.

Early Days: Native Americans and European Settlers

People have lived or used the lower parts of the Esopus Creek for at least 4,000 years. Native Americans used the flat areas along the lower Esopus for growing corn. They also had apple orchards in the area now covered by the reservoir. They mostly hunted in the higher parts of the valley.

The Esopus Creek was important for early European settlers. The creek is named after the Lenape tribe who lived there. In 1609, Henry Hudson explored the river, and European traders soon followed, looking for beaver furs. The Dutch built a settlement called Wiltwyck (now Kingston) in 1649. This location was perfect for trading with the Native Americans.

Growth and Industry: 1704–1885

In the early 1700s, a large land grant called the Hardenbugh Patent was made. This grant covered much of the Catskills, including the Esopus Valley. This led to some land disputes that lasted for many years.

Permanent settlements in the Esopus valley began in the mid-1700s. These communities often relied on forest products. Loggers cut down trees for sawmills, and furniture makers set up shops. A road, the Ulster, Delaware and Dutchess Turnpike, was built along the valley. Later, the Ulster and Delaware Railroad followed the same path.

Besides timber, other industries thrived. Tanners used hemlock bark to treat cowhides. Many charcoal kilns (ovens for making charcoal) were also in the Esopus Valley. Bluestone (a type of rock) was quarried from the hills and even from the creek bed.

By the late 1800s, these industries started to decline as most easily accessible forests had been cut down.

New Beginnings: Recreation and Water Supply (1885–1973)

In 1885, the Forest Preserve was created to protect forests in New York, including the Catskills. This meant the land had to be kept "forever wild." As industries declined, a new one grew: mountain tourism. People from cities came to the Catskills to enjoy nature and escape the summer heat.

Fishing became very popular. Early anglers preferred the smaller streams for brook trout. However, in the 1880s, rainbow trout were introduced to the Esopus. These fish could handle warmer water and soon became the main fish in the creek. The Esopus became a famous fishing spot.

One special place was Winnisook Lake, the source of the Esopus. In 1887, Alton B. Parker and his friends bought land there and created the lake for their private enjoyment.

In the early 1900s, New York City needed more water. After much discussion, the state allowed the city to build reservoirs in the Esopus and Schoharie watersheds. Local residents tried to stop the project because it would force people to move and change the landscape. However, the city went ahead, and the Ashokan Reservoir was finished in 1913. It started sending water to the city in 1915 through the Catskill Aqueduct.

The reservoir was designed with two parts to help clear the water. Water from the upper Esopus flows into the western part, where mud and silt can settle. The cleaner water then flows into the eastern part, which feeds the aqueduct.

The water released from the Shandaken Tunnel (the Portal) made parts of the Esopus a whitewater stream. This led to whitewater slalom races and, later, a popular tubing industry in the summer.

Modern Challenges: Floods and Water Management (1974–Present)

In recent decades, the population in the upper Esopus valley has grown. This has led to some disagreements between homeowners, people who use the creek for fun, and New York City. These groups now work together to manage the creek.

In the 1970s, anglers (fishermen) and the city argued about how much water was released from the Portal. Fishermen said the city's releases were harming trout. In 1976, a state law was passed allowing the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to control water releases from the reservoirs.

Large floods have also been a problem. In 1980, a big storm caused severe flooding in the upper Esopus, damaging roads and bridges. In 1996, another flood caused a lot of mud and clay to wash into the Schoharie Reservoir. This muddy water was then released into the Esopus through the tunnel, making the creek very cloudy for years. Fishermen were upset because the mud affected trout fishing. In 2003, a judge fined New York City for muddying the creek and ordered it to get a state permit for its discharges.

In 2005, another heavy rain caused the third-worst flood in the creek's recorded history. Roads were closed, and many homes were damaged. In 2010, the city started releasing muddy water from the reservoir into the lower Esopus to clear the reservoir. This caused more complaints from local communities.

The worst flood happened in August 2011 when Hurricane Irene hit the Catskills. Record amounts of rain fell, causing huge floods. Homes and businesses were severely damaged, and many roads and bridges were washed away. Two weeks later, Tropical Storm Lee brought even more rain and flooding.

Farmers along the lower Esopus were especially affected, with some fields under 10 feet (3.0 m) of water. The creek remained muddy for months as the city continued to release water from the reservoir. Local officials criticized the city, saying it should manage the reservoir better to prevent flooding downstream. The city argued it had to choose between "mud or flood."

Today, the city continues to work with local communities to manage the creek. They are trying to balance the city's water needs with the well-being of the local environment and residents.

Fun on the Esopus: Recreation

The Esopus Creek offers many ways to enjoy the outdoors.

Fishing for Trout and Bass

Fishing has been popular on the Esopus for a long time. In the 1800s, people started coming from outside the area just to fish here.

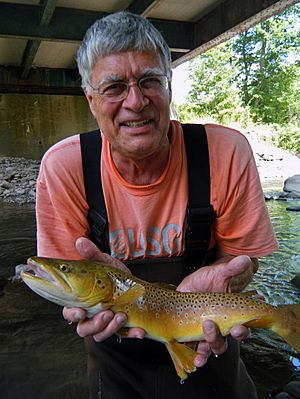

Today, the upper Esopus is a famous spot for anglers who fly-fish for trout. Much of the land along the creek is public, making it easy to access. The Esopus was one of the first places in the Catskills where rainbow trout were successfully introduced. Now, it's known as one of the best wild-trout streams in the Northeast. The state also adds brown trout to the creek. Because brown trout spawn later, the fishing season on the Esopus lasts until November 30, longer than most other streams.

The Esopus is special because it has no minimum size limit for trout. Most fish caught are less than 12 inches (30 cm) long. However, a very large brown trout, weighing 19 pounds 4 ounces (8.7 kg), was caught here in 1923, setting a state record that lasted for 30 years!

Anglers often divide the upper Esopus into four sections for fishing:

- The small Esopus (from Winnisook Lake to Big Indian)

- The big Esopus (from Big Indian to the Portal)

- The big Esopus (from the Portal to Phoenicia)

- The big Esopus (from Phoenicia to the reservoir)

You can also fish for trout, walleye, bass, and crappie in the Ashokan Reservoir. You need a permit from the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and a state fishing license. Only unpowered boats are allowed on the reservoir.

The creek's estuary (where it meets the Hudson) near Saugerties is a popular spot for bass fishing. Both largemouth and smallmouths are caught here. Striped bass from the Hudson River also come to the estuarine Esopus to spawn.

Boating Adventures

Canoeists and kayakers enjoy the stretch of the Esopus from Allaben (above the Portal) to Boiceville (above the reservoir). They usually go when the water levels are high enough, often after heavy rains or when water is released from the Portal. This section has whitewater rapids that are Class II or III on the International scale of river difficulty. It's great for both experienced and new paddlers.

The Kayak and Canoe Club of New York holds an annual whitewater slalom race here. The American Canoe Association also hosts its Atlantic Division Championships on the Esopus every fall.

The lower Esopus is good for those who prefer calm, flatwater boating. Marinas in Saugerties offer places to keep boats used on the Hudson River.

Tubing the Esopus near Phoenicia is very popular, with about 15,000 people doing it each year. Local businesses rent tubes to visitors, making it a big summer attraction. You can choose between a wilder, more challenging section north of Phoenicia (not for kids) or a calmer section below it. If you take the calmer option, you can ride the Catskill Mountain Railroad back! Tubes are rented only when the water level is safe.

Caring for the Esopus: Conservation and Management

The upper and lower parts of the Esopus Creek have different conservation needs because of the reservoir. The upper stream is managed more closely because it's a major source of New York City's drinking water and an important place for recreation. The lower stream is not a drinking water source, and its surrounding land is more farmed. Conservation efforts there focus on its natural beauty and environment.

Upper Esopus: Protecting a Water Source

The upper Esopus is in both the Catskill Park and the New York City watershed. It's closely watched by the state DEC and the city DEP. Most of the land in the upper watershed is forested. Trout fishermen also work to keep the water clean.

A management plan for the upper Esopus focuses on keeping the water quality good. People who own property along the creek are concerned about flooding and erosion. The plan suggests avoiding new buildings on the flood plain and improving flood control systems.

The Shandaken Tunnel's effect on fishing is still a topic of discussion. Some fishermen believe the muddy and warm water from the tunnel has harmed the rainbow trout population. Environmental groups have suggested that the city should be able to take water from different depths of the Schoharie Reservoir to get cleaner water.

Boaters and tubers rely on the water releases from the Portal to make their activities possible. Sometimes, large pieces of wood (like trees or branches) fall into the stream during floods. These can create good homes for fish but can be dangerous for boats.

Riparian buffers (areas of plants along the riverbanks) are also important. Most of the upper Esopus has good buffers, but some parts have very little. These buffers help control erosion and provide shade.

Dealing with Invasive Species

In recent years, Japanese knotweed, an invasive species, has been found along the creek banks. This plant is bad for the stream because it doesn't provide much shade, isn't good at stopping erosion, and blocks access to the water. Oriental bittersweet, another invasive vine, also harms trees in the buffer forests. Plans are being made to control these species.

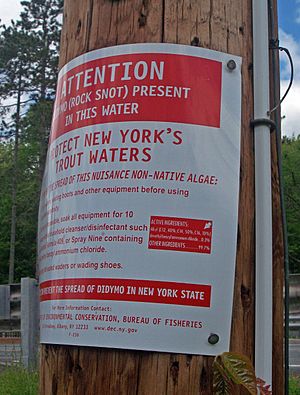

In 2009, "rock snot" (Didymosphenia geminata), a type of algae, was found in the creek. This algae can clog water pipes but isn't harmful to people. However, it can cover the river bottom, harming insects that trout eat. There's no way to get rid of it, so fishermen are advised to clean their waders carefully to prevent its spread. Studies have shown that the algae hasn't significantly harmed the fish population in the Esopus, possibly because of the mud and other substances in the water.

Lower Esopus: Local Efforts

Conservation efforts for the lower Esopus are mainly led by local towns. After the 2005 flood, towns along the lower Esopus and the city of Kingston started holding an annual conference to discuss the watershed.

Farmers in Marbletown were hit hard by the 2005 flood. Silt and mud covered their fields. Marbletown plans to work with farmers to protect land outside the flood plain and preserve rare plants and animals.

Concerns about flooding have also led to criticism of the DEP. Some people believe the reservoir is kept too full, causing more water to be released during heavy rains and making floods worse. The city has started using new software to monitor water levels more closely.

In Saugerties, the Esopus Creek Conservancy works to protect the land and ecosystems around the creek. They created the 161-acre (65 ha) Esopus Bend Nature Preserve, which protects a long stretch of important habitat. Trails in the preserve offer great views of the creek.

In 2007, the Lower Esopus Watershed Partnership (LEWP) was formed. This group of towns works together to help people appreciate and care for the lower Esopus watershed.

Tributaries: Streams that Feed the Esopus

Many smaller streams flow into the Esopus Creek, adding to its water and shaping its path. Here are some of them:

- Birch Creek

- Bushnellsville Creek

- Elk Bushkill

- Fox Hollow Brook

- Giant Ledge Stream

- Hanging Birds Nest Brook

- Hatchery Hollow Brook

- Seneca Hollow Stream

- Maben Hollow Brook

- McKenley Hollow Brook

- Lost Clove Creek

- Shandaken Tunnel

- Peck Hollow Creek

- Broadstreet Hollow Creek

- Woodland Creek

- Stony Clove Creek

- Beaver Kill

- Little Beaver Kill

- Bush Kill

- Saw Kill

- Plattekill Creek

- Tannery Brook (Saugerties)

- Tannery Brook (Kingston)

- Stony Creek

Images for kids

-

Ashokan Reservoir from Overlook Mountain

-

Oak-hickory Southern hardwood forest alongside Esopus at Beechford

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |