Common starling facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Common starling |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Sturnidae |

| Genus: | Sturnus |

| Species: |

S. vulgaris

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sturnus vulgaris |

|

|

|

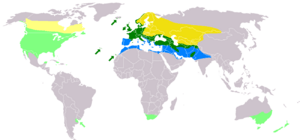

| Native: Summer visitor Resident Winter visitor

Introduced: Summer visitor Resident |

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The common starling or European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) is a medium-sized bird from the starling family. In Great Britain and Ireland, it is often just called the starling. This bird is about 20 cm (8 in) long. It has shiny black feathers that look purple or green in the light. In some seasons, its feathers are speckled with white spots.

Its legs are pink, and its beak changes color: it's black in winter and yellow in summer. Young starlings have browner feathers than adult birds. Starlings are known for being noisy, especially when they gather in large groups. Their song is not very musical, but it is very varied. They are also great at copying sounds. Famous writers like William Shakespeare have even mentioned this ability.

Common starlings have about 12 different types of subspecies. They live in open areas across Europe and Asia, all the way to Mongolia. They have also been brought to many other places like Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, and South Africa. Some starlings stay in one place all year, especially in western and southern Europe. But others, from colder northern areas, fly south and west for the winter.

The common starling builds a messy nest in holes in trees or buildings. Females lay four or five glossy, pale blue eggs. These eggs hatch in about two weeks, and the young birds stay in the nest for another three weeks. Starlings usually have one or two families of chicks each year. These birds eat many different things, including invertebrates (like insects and worms), as well as seeds and fruit. They are hunted by various mammals and birds of prey. They can also have many tiny parasites living on or inside them.

Large groups of starlings can help farmers by eating insect pests. However, starlings can also be pests themselves if they eat fruit or young crops. Their large roosts in cities can also cause problems with noise and mess. In places where they were introduced, people have tried different ways to control their numbers, like culling (killing them). But these efforts have not been very successful, except in stopping them from spreading to Western Australia.

Since the 1980s, the number of common starlings has gone down in parts of northern and western Europe. This is because there are fewer insects in grasslands for their chicks to eat. Even so, there are still a huge number of starlings worldwide. Their total population is not dropping much, so the International Union for the Conservation of Nature says the common starling is a species of Least Concern, meaning it's not currently at risk of disappearing.

Contents

Starling Names and Family

The common starling was first described by a scientist named Carl Linnaeus in 1758. He gave it the scientific name Sturnus vulgaris. Sturnus is Latin for "starling," and vulgaris means "common." The word "starling" has been used for a long time, since the 11th century.

The starling family, called Sturnidae, mostly lives in the Old World (Europe, Asia, and Africa). The common starling's closest relative is the spotless starling. Some scientists think the spotless starling might even be a type of common starling.

Different Types of Starlings

There are several different types, or subspecies, of the common starling. They vary a bit in size and the color of their feathers. These differences change gradually across their habitats. Because of this, scientists sometimes disagree on how many subspecies there are.

- Subspecies

-

S. v. tauricus in Ukraine

-

S. v. faroensis in the Faroe Islands

-

S. v. vulgaris in Germany

| Subspecies | Scientist | Where it lives | What makes it special |

|---|---|---|---|

| European starling (S. v. vulgaris) |

Linnaeus, 1758 | Most of Europe, plus Iceland and the Canary Islands | This is the most common type. |

| Faroe starling (S. v. faroensis) |

Feilden, 1872 | the Faroe Islands | A bit bigger than the common type, especially its beak and feet. Its green feathers are darker and duller. |

| Shetland starling (S. v. zetlandicus) |

Hartert, 1918. | the Shetland Islands | Similar to the Faroe starling, but in between the Faroe and common types in size. |

| Azores starling (S. v. granti) |

Hartert, 1903 | the Azores | Smaller than the common type, especially its feet. Often has a strong purple shine on its back. |

| Siberian starling (S. v. poltaratskyi) |

(Finsch, 1878) | Eastern Russia, through the Ural Mountains to Mongolia | Its head is mostly purple, its back is green, and its sides are usually bluish-purple. |

| Black Sea starling (S. v. tauricus) |

Buturlin, 1904 | Around the Black Sea coast, from Crimea to western Asia Minor | Has longer wings. Its head is green, and its body is bronze-purple. |

| Eastern Turkey starling (S. v. purpurascens) |

Gould, 1868 | Eastern Turkey to Lake Sevan | Has longer wings. Green shine is only on its ear-coverts, neck, and upper chest. |

| Caucasian starling (S. v. caucasicus) |

Lorenz, 1887 | the Volga Delta and eastern Caucasus | Green shine on its head and back, purple shine on its neck and belly. |

| Central Asian starling (S. v. porphyronotus) |

(Sharpe, 1888) | Western Central Asia | Very similar to tauricus, but smaller. |

| Hume's starling or Afghan starling (S. v. nobilior) |

(Hume, 1879) | Afghanistan, southeastern Turkmenistan to eastern Iran | Similar to purpurascens, but smaller with shorter wings. |

| Himalayan starling (S. v. humii) |

(Brooks, 1876) | Kashmir to Nepal | Small. Purple shine is mostly on its neck, otherwise it's green. |

| Sindh starling (S. v. minor) |

(Hume, 1873) | Pakistan | Small. Green shine is on its head, lower belly, and back, otherwise it's purple. |

What Starlings Look Like

The common starling is about 19 to 23 cm (7.5 to 9 in) long. Its wingspan is 31 to 44 cm (12 to 17 in), and it weighs between 58 and 101 g (2.0 to 3.6 oz). Its feathers are shiny black, with purple or green colors that shimmer in the light. In winter, it has white spots. Male starlings have fewer spots on their bellies than females. The throat feathers of males are long and loose, which they use to show off. Female throat feathers are smaller.

Their legs are strong and pinkish-red. Their beak is thin and pointed. In winter, it's brownish-black. In summer, females have bright yellow beaks, while males have yellow beaks with blue-grey bases. Starlings change their feathers once a year in late summer. New feathers have white or buff tips, making the bird look speckled. These tips wear off by the breeding season, making the bird look less spotted.

Young starlings are grey-brown. By their first winter, they look like adults, but might still have some brown feathers, especially on their heads. You can often tell if a starling is male or female by its eyes. Males have rich brown irises, while females have mouse-brown or grey ones.

Starlings are easy to spot because of their short tails, sharp beaks, round bodies, and strong, reddish legs. When they fly, their pointed wings and dark color stand out. On the ground, they have a unique, waddling walk. They are different from the spotless starling because adult common starlings have iridescent spots, while spotless starlings do not.

Like most starlings, they walk or run instead of hopping. Their flight is strong and direct. Their triangular wings beat very fast, and they often glide for short distances. When many starlings fly together, they move as one big group, changing direction at the same time. This is called a "murmuration." Starlings can fly very fast when migrating, up to 80 km/h (50 mph), and can travel up to 1,500 km (930 mi).

Common starlings have special skulls and muscles that help them find food. They can stick their beak into the ground and open it wide to search for hidden insects. This skill has helped them spread to many places.

Starling Sounds

The common starling is a very noisy bird. Its song is a mix of musical and mechanical sounds. Male starlings sing for a minute or more, especially when trying to attract a mate. Their songs often include sounds copied from other birds or even human-made noises. They are so good at copying sounds that they might mimic a sound they've only heard once! Each starling has its own collection of songs and clicks.

Males sing a lot before the breeding season. Once they find a mate, they sing less often. If a female is nearby, a male might fly to his nest and sing from the entrance to invite her in. Older starlings usually have more songs in their collection than younger ones. Males who sing longer and have more complex songs tend to find mates earlier and have more success raising chicks. Females seem to like complex songs, perhaps because it shows the male is experienced. A complex song also helps a male defend his territory.

Male starlings have a much larger voice box (called a syrinx) than females. This helps them sing their complex songs.

Starlings also sing outside the breeding season, except when they are changing their feathers. This singing is usually done by males, but females sometimes sing too. The reason for this out-of-season singing is not fully understood. Starlings also have many other calls, like flock calls, threat calls, and alarm calls. When they are looking for food together, they squabble a lot. They also chatter loudly when roosting or bathing, which can annoy people living nearby. When a large flock flies together, the sound of their wings makes a distinct whooshing noise that can be heard far away.

How Starlings Live

Common starlings are very social birds, especially in autumn and winter. They form huge, noisy groups called "murmurations" near their roosting spots. These dense groups are thought to protect them from birds of prey like peregrine falcons. The flocks fly in a tight, sphere-like shape, constantly expanding, shrinking, and changing form. It looks like there's no leader, but each bird changes its path based on its closest neighbors.

Very large roosts, with up to 1.5 million birds, can form in cities, forests, and reedbeds. Their droppings can cause problems, sometimes piling up to 30 cm (12 in) deep and harming trees. In smaller amounts, the droppings act as fertilizer.

Huge flocks of starlings, sometimes over a million birds, can be seen just before sunset in Denmark. This happens in spring when birds gather before flying to their breeding grounds. Their group flying creates amazing shapes against the sky, a sight known as sort sol ("black sun"). In the UK, flocks of five to fifty thousand starlings form in mid-winter, also called murmurations.

What Starlings Eat

Common starlings mostly eat insects and other small creatures. Their diet includes spiders, crane flies, moths, beetles, bees, wasps, and ants. They eat both adult insects and their larvae. Starlings also eat earthworms, snails, small amphibians, and lizards. Eating insects is very important for them to successfully raise their young.

However, starlings are omnivores, meaning they eat both plants and animals. They can also eat grains, seeds, fruits, nectar, and food waste if they find it. Starlings have trouble digesting some sugary fruits, but they can eat grapes and cherries. The starlings on the Azores islands even eat the eggs of the endangered roseate tern. People are trying to control starling numbers there to protect the terns.

Starlings use several ways to find food. Most of the time, they look for food close to the ground, picking up insects from the surface or just below it. They prefer to search in short grass and often feed near grazing animals or even perch on their backs to eat parasites. In large flocks, birds at the back will fly to the front where the food is best. This is called "roller-feeding."

One common way starlings find food is called "probing." They stick their beak into the ground repeatedly until they find an insect. They might also open their beak in the soil to make a hole bigger. Young starlings take time to learn this skill, so their diet might have fewer insects. Starlings also catch flying insects in the air ("hawking") or lunge forward to catch moving insects on the ground. They pull earthworms out of the soil. If starlings don't have enough food, they can gain weight by storing fat in their bodies.

Building a Nest

Male starlings find a good hole and start building a nest to attract females. They often decorate the nest with flowers and fresh green plants. The female might take these decorations apart after she accepts him as a mate. The smell of plants like yarrow seems to help attract females.

Males sing a lot while building the nest and even more when a female comes near. Nests can be in any type of hole, like hollow trees, buildings, tree stumps, or nest boxes. Nests are usually made of straw, dry grass, and twigs, with a soft lining of feathers, wool, and leaves. Building the nest usually takes four or five days and can continue even after the eggs are laid.

Common starlings can be monogamous (one male, one female) or polygamous (one male, multiple females). Usually, one male and one female raise the chicks, but sometimes another bird might help. Starlings can live in colonies, with many nests in the same or nearby trees. A male might mate with a second female while the first one is still on the nest. However, the chicks from the second nest usually don't do as well as those from the first.

Raising Young Starlings

Starlings breed in spring and summer. The female lays one egg each day for several days. If an egg is lost, she will lay another to replace it. There are usually four or five eggs. They are oval-shaped, pale blue or sometimes white, and often look shiny. The eggs are about 26.5 to 34.5 mm (1.04 to 1.36 in) long and 20.0 to 22.5 mm (0.79 to 0.89 in) wide.

The eggs hatch in about 13 days. Both parents take turns sitting on the eggs, but the female spends more time incubating them, especially at night. The young chicks are born blind and without feathers. They grow soft downy feathers within seven days and can see within nine days. Once the chicks can control their body temperature (about six days after hatching), the adults stop removing their droppings from the nest. This is because the droppings would make the chicks and nest wet, which could make them cold.

The chicks stay in the nest for three weeks, and both parents feed them constantly. After they leave the nest, the parents continue to feed them for another one or two weeks. A pair can raise up to three families of chicks per year, often reusing the same nest. However, two families are more common, and only one in colder northern areas. Within two months, most young starlings will have changed their feathers and gained their first adult-like plumage. They get their full adult feathers the next year. Like other birds, starlings keep their nests clean by removing the chicks' waste.

Sometimes, other female starlings (who don't have a mate) will lay their eggs in another pair's nest. This is called "brood parasitism." Common starling nests have a 48% to 79% success rate for chicks leaving the nest. However, only about 20% of these young birds survive to become adults and breed. Adult starlings have a better survival rate, around 60%. Starlings usually live for about 2 to 3 years, but one lived for almost 23 years!

Dangers and Health

Most animals that hunt starlings are other birds. When starlings are in a group, they often fly away in wavy, agile patterns to escape. Their flying skills are hard for birds of prey to match. Adult starlings are hunted by hawks like the northern goshawk and Eurasian sparrowhawk, and falcons like the peregrine falcon and common kestrel. Slower birds of prey, like black and red kites, tend to catch younger or less experienced starlings. At night, when starlings are roosting in groups, they can be caught by owls.

More than twenty types of hawks, owls, and falcons are known to hunt starlings in North America. The most common predators of adult starlings in cities are likely peregrine falcons. Mammals that can climb, like stoats, raccoons, and squirrels, might raid nests. Cats can also catch starlings that are not careful.

Common starlings can have many different parasites. One study found that all starlings had at least one type of parasite. Most had external parasites like fleas, mites, or ticks, and many had internal parasites like worms.

The hen flea is the most common flea found in starling nests. Other tiny creatures like lice and mites can also live on starlings. Some flying insects, like louse-flies, also parasitize starlings. Larvae of certain moths can live in nests and eat waste or dead chicks. Starlings can also get tiny blood parasites and a bright red worm called a gapeworm. This worm moves to the windpipe and can make it hard for the bird to breathe.

Starlings can also get diseases like avian tuberculosis and avian malaria.

Where Starlings Live Around the World

In 2004, there were an estimated 310 million common starlings worldwide. They live across a huge area of 8.87 million square kilometers (3.42 million square miles). They are native to Europe and Asia, found throughout Europe, northern Africa, India, Nepal, the Middle East, and northwestern China.

Starlings in southern and western Europe usually stay in one place. But populations from colder northern areas, where winters are harsh and food is scarce, migrate south or southwest. In autumn, many starlings from northern Europe, Russia, and Ukraine fly south. At the same time, many starlings from Britain fly to Spain and North Africa. Starlings have also been seen in Japan and Hong Kong, but it's not clear where they came from. In North America, northern starlings also migrate, leaving Canada in winter and flying south.

Common starlings prefer cities or suburbs where buildings and trees offer good places to nest and roost. They also like reedbeds for roosting. They often feed in grassy areas like farms, pastures, playing fields, and golf courses, where short grass makes it easy to find food. They can live in open forests and shrubby areas. Starlings rarely live in dense, wet forests. They are also found in coastal areas, nesting on cliffs and feeding among seaweed. Their ability to live in many different places has helped them spread around the world, from coastal wetlands to mountain forests high above sea level.

Starlings in New Places

The common starling has been introduced to and successfully settled in New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, North America, Fiji, and several Caribbean islands. From these places, they have also spread to Thailand, Southeast Asia, and New Guinea.

South America

In 1987, a small group of starlings was seen nesting in gardens in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Since then, they have been spreading their breeding area by about 7.5 km (4.7 mi) each year. In Argentina, they use many natural and man-made nesting spots, especially holes made by woodpeckers.

Australia

Common starlings were brought to Australia to eat insect pests on farms. Early settlers thought starlings would also help pollinate flax, an important crop. Nest boxes were even put out for them. Starlings were introduced to Melbourne in 1857 and Sydney twenty years later. By the 1880s, they were well-established in the southeast. But by the 1920s, they were seen as pests. Even though starlings were first seen in Western Australia in 1917, they have mostly been stopped from spreading there. The wide, dry Nullarbor Plain acts as a natural barrier, and control efforts have killed many birds. Starlings have also settled on several Australian islands.

New Zealand

Early settlers in New Zealand cleared forests, and their new crops were attacked by many insects. Native birds were not used to living near people, so starlings were brought from Europe to control the pests. They were first brought in 1862, and more followed. The birds quickly settled and are now found all over New Zealand, including distant islands.

North America

After two tries, about 60 common starlings were released in 1890 in New York's Central Park. This was done by Eugene Schieffelin, who reportedly wanted to introduce every bird mentioned in William Shakespeare's plays to North America. Around the same time, 35 pairs were released in Portland, Oregon, but they disappeared later. Starlings reappeared in the Pacific Northwest in the 1940s, likely from the Central Park birds. The original 60 birds have now grown to 150 million, spreading from southern Canada to Central America.

Polynesia

The common starling seems to have arrived in Fiji in 1925. It might have come from New Zealand. Its spread in Fiji has been limited. Tonga was settled around the same time, and the birds there have been slowly spreading north.

South Africa

In South Africa, the common starling was introduced in 1897 by Cecil Rhodes. It spread slowly and is now common in the southern Cape region. It lives in areas with people and farms, especially where there is irrigated land. It avoids dry areas where it can't find insects. Starlings might compete with native birds for nesting holes, but native birds are probably more affected by habitat loss. They breed from September to December. Outside breeding season, they gather in large flocks, often roosting in reedbeds. They are the most common bird in urban and farming areas.

West Indies

In 1901, people in Saint Kitts asked for starlings to help with a grasshopper problem that was damaging their crops. The common starling was brought to Jamaica in 1903. The Bahamas and Cuba were naturally settled by starlings from the US. This bird is quite common in Jamaica, Grand Bahama, and Bimini, but rare in other parts of the Bahamas and eastern Cuba.

Starling Numbers

The total number of common starlings worldwide is estimated to be over 310 million. Their numbers are not thought to be dropping much, so the International Union for the Conservation of Nature lists them as being of Least Concern. This means they are not currently at risk of disappearing.

From the 1800s to the 1950s and 60s, starling numbers increased greatly across Europe. They spread into Ireland and parts of Scotland where they hadn't lived before. They also started breeding in northern Sweden from 1850 and in Iceland from 1935. Their breeding range expanded through southern France to northeastern Spain, and into Italy, Austria, and Finland. They began breeding in Spain in 1960.

However, since 1980, there have been big drops in starling numbers in Sweden, Finland, northern Russia, and the Baltic states. Smaller drops have happened in other parts of northern and central Europe. In these areas, intensive farming has harmed the birds. In several countries, starlings are now on "red lists" because their populations have dropped by more than 50%. In the United Kingdom, numbers fell by over 80% between 1966 and 2004. This decline seems to be because young birds are not surviving as well, possibly due to changes in farming. Modern farming methods in northern Europe mean there are fewer grasslands and meadows, which means less food (insects) for young starlings.

Starlings and People

Good and Bad Sides

Since common starlings eat insect pests like wireworms, they are seen as helpful in northern Europe and Asia. This was one reason they were brought to other places. In the former Soviet Union, about 25 million nest boxes were put up for starlings. In New Zealand, starlings were good at controlling a type of grass grub. Even in the US, where starlings are considered pests, the government admits that starlings eat huge numbers of insects.

When starlings are introduced to new places, they can cause problems for native birds by competing for nesting holes. In North America, they might affect chickadees, nuthatches, woodpeckers, and swallows. In Australia, they compete with parrots for nesting sites. Because of their role in harming native species and damaging farms, the common starling is on a list of the world's 100 worst invasive species.

European starlings can live in many different places and use many food sources and nesting spots. They live easily with humans, which helps them take over from other native birds, especially woodpeckers. Starlings are aggressive omnivores and use a special "bill probing" technique (described earlier) to find food, which gives them an advantage over birds that only eat fruit. Their aggressive behavior when it comes to food helps them outcompete native species. Starlings are also aggressive when making their nests. They often take over a nest site, like a tree hole, and quickly fill it with nesting material, unlike other birds that use little or no bedding.

Common starlings can eat and damage fruit in orchards, such as grapes, peaches, olives, and tomatoes. They can also dig up newly planted grain and young crops. They might also eat animal feed and spread weed seeds through their droppings. In eastern Australia, weeds like bridal creeper are thought to have been spread by starlings. Damage to farms in the US is estimated to cost about US$800 million each year.

The large size of starling flocks can also cause problems. Starlings can be sucked into airplane jet engines. One of the worst incidents happened in Boston in 1960, when 62 people died after an airliner flew into a flock and crashed into the sea. Large starling roosts are a safety risk for aircraft because they can clog engines and cause planes to fall. From 1990 to 2001, there were 852 reports of starlings causing problems for aircraft, with 39 strikes causing major damage.

Starling droppings can contain a fungus called Histoplasma capsulatum, which can cause a disease called histoplasmosis in humans. This fungus can grow well in large piles of droppings at roosting sites. Starlings can also potentially spread other infectious diseases to humans and livestock. For example, the spread of Histoplasmosis from starlings was reported to cause the loss of 10,000 pigs at a farm.

Controlling Starlings

Because starlings can damage crops, people have tried to control their numbers. In some places, like Spain, starlings are hunted for food during certain times of the year. In France, they are considered pests and can be killed for most of the year. In Great Britain, starlings are protected by law, making it illegal to intentionally kill them or destroy their nests. However, in Northern Ireland, people can get a license to control starlings if they are causing serious damage to farms or public safety. Since starlings migrate, birds involved in control efforts might come from far away, so breeding populations might not be affected much. Non-lethal methods, like using loud noises or visual devices to scare them, only work for a short time.

Huge starling roosts in cities can cause problems with noise, mess, and the smell of droppings. In 1949, so many starlings landed on the clock hands of London's Big Ben that it stopped! People tried to get rid of the roosts using nets, chemicals, and playing starling alarm calls, but it didn't work very well.

In places where starlings have been introduced, there are no laws protecting them, and big control plans might be started. You can stop starlings from using nest boxes by making sure the entrance holes are smaller than 3.8 cm (1.5 in), which is the size they need. Removing perches can also discourage them from visiting bird feeders.

Western Australia banned the import of starlings in 1895. New flocks arriving from the east are regularly shot, and younger starlings are trapped. New methods are being developed, like tagging one bird and tracking it to find where the flock roosts. By 2009, only 300 common starlings were left in Western Australia, and the state continued its efforts to get rid of them.

In the United States, common starlings are not protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. This means no permit is needed to remove their nests and eggs or to kill young or adult starlings. In 2008, the US government poisoned, shot, or trapped 1.7 million starlings, more than any other pest species. In 2005, there were an estimated 140 million starlings in the United States, which was about 45% of the total world population.

One way to control starlings on farms is to use a special poison called Starlicide. This has been found to reduce the spread of certain diseases in livestock. Another idea is to use types of animal feed that starlings don't like as much, such as larger pieces of food. Keeping livestock feeding areas away from starling roosts can also help. Starlings are more likely to visit feeding operations in colder weather or after snowstorms.

Starlings in Science and Art

Common starlings can be kept as pets or used in labs for studies. The famous animal scientist Konrad Lorenz called them "the poor man's dog" because young starlings are easy to get and care for. They adapt well to being kept in cages and eat regular bird food and mealworms. Several starlings can be kept in the same cage, and they are curious, making them easy to train or study. The only downsides are their messy droppings and the need to be careful about diseases they might spread to humans. In labs, starlings are second only to domestic pigeons in how many are used.

The common starling's ability to copy sounds has been known for a long time. In an old Welsh story, a queen named Branwen trained a starling to speak words and sent it with a message across the sea. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder said that starlings could be taught to speak whole sentences in Latin and Greek. In one of William Shakespeare's plays, a character named Hotspur says he will get a starling to say nothing but "Mortimer" to annoy the king.

The famous composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart had a pet common starling that could sing part of one of his piano concertos. He bought it after hearing it sing a tune he had written six weeks earlier, which hadn't even been performed yet! He loved the bird very much and held a special funeral for it when it died. Some people think one of his funny musical pieces might have been inspired by the starling's varied calls. Other people who have owned starlings say how good they are at picking up phrases and words. The words don't mean anything to the starling, so they often mix them up or use them at strange times in their songs. Their mimicry is so good that people sometimes look for a human they think they just heard speaking!

In some Arab countries, starlings are trapped for food. Their meat is tough and not very good quality, so it's usually stewed or made into a paste. Even when cooked properly, some people might still find it an acquired taste.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Estornino pinto para niños

In Spanish: Estornino pinto para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |