History of Belize facts for kids

The history of Belize is a really old story, going back thousands of years! Long, long ago, the amazing Maya civilization lived in the area we now call Belize. They were here from about 1500 BC to 1200 BC and were very powerful until around 1000 AD.

You can still see signs of their advanced culture today. Places like Cahal Pech, Caracol, Lamanai, Lubaantun, Altun Ha, and Xunantunich are ancient Maya cities. They show us how many people lived here and how smart they were.

Later, in the 1500s, European explorers and missionaries from Spain arrived. They were the first Europeans to visit this region. One big reason people came here was for a special tree called logwood. The British also came for this wood and started to settle.

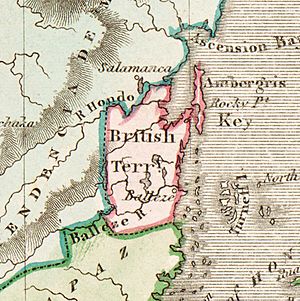

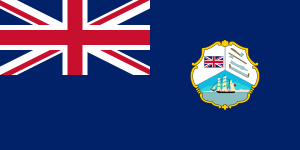

Belize wasn't officially called the "Colony of British Honduras" until 1862. It became a "crown colony" in 1871, which meant it was directly ruled by the British King or Queen. Over time, Belize gained more power to govern itself. It became internally self-governing in January 1964. The name changed from British Honduras to Belize in June 1973. Finally, Belize became a fully independent country on 21 September 1981.

Contents

Ancient Maya Civilization: A Look Back

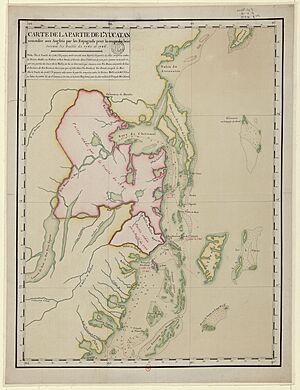

The Maya civilization started more than 3,000 years ago. It grew in areas like the Yucatán Peninsula and southern highlands. This includes parts of what is now southeastern Mexico, Guatemala, western Honduras, and Belize. Even after nearly 500 years of European influence, many parts of their culture still exist.

Early Maya Life: Farmers and Villages

Before about 2500 BC, some groups of hunters and gatherers began to settle down. They started small farming villages. They learned to grow important crops like corn, beans, squash, and chili peppers. Over time, many different languages and cultures developed within the Maya world.

The Rise of Maya Cities

Between about 2500 BC and 250 AD, the main parts of Maya civilization began to form. The best time for this civilization was during the Classic Period, which started around 250 AD.

In the southern and central parts of Belize, the city of Caracol was very important. The writings on its monuments were in a special language called Classic Ch'olti'an. North of the Maya Mountains, the language at Lamanai was Yucatecan by 625 AD. The last date written in Ch'olti'an in Belize was in 859 AD at Caracol. The Yucatec culture in Lamanai lasted even longer.

Maya Skills and Achievements

Maya farmers used different ways to grow food. This included systems with irrigated fields and also "slash-and-burn" farming. Their food fed many people: skilled craft makers, traders, warriors, and priest-astronomers. These priests studied the sun, moon, planets, and stars. They created a complex math system and a calendar. They used these to plan farming and religious events. They also recorded important events on carved stone monuments called stelae.

The Maya were very good artists. They made pottery, carved beautiful jade, shaped flint tools, and created amazing costumes with feathers. Their buildings included temples and palaces, often built around open plazas. These structures were made of cut stone, covered with stucco, and decorated with carvings and paintings.

Important Maya Sites in Belize

Belize has some of the oldest Maya settlements. It also has grand ruins from the Classic Period and examples of later buildings.

- Cuello, near Orange Walk, is a very old site, possibly from 2,500 BC. Pottery found there is some of the oldest in Mexico and Central America.

- Cerros, on Chetumal Bay, was a busy trading and religious center between 300 BC and 100 AD.

- One of the most famous jade carvings, a head thought to be the sun god Kinich Ahau, was found at Altún Ha. This site is near Belize City.

- Other important Maya centers in Belize include Xunantunich and Baking Pot in Cayo District, Lubaantún and Nimli Punit in Toledo District, and Lamanai in Orange Walk District.

The Decline of Maya Civilization

During the late Classic Period, it's thought that between 400,000 and 1,000,000 people lived in the area that is now Belize. People settled almost everywhere they could farm. But in the 900s AD, Maya society faced big problems. Building new public structures stopped. The main cities lost their power. The population went down as their social and economic systems fell apart.

Some people still lived in or returned to sites like Altun Ha, Xunantunich, and Lamanai. But these places were no longer important centers for ceremonies or government. Why the Maya civilization declined is still a mystery. Many experts now believe it wasn't one single reason. Instead, it was a mix of complex problems that happened at different times in different areas.

European Arrival and Early Colonial Times

Many Maya people were still living in Belize when Europeans arrived in the 1500s and 1600s. Old records and archaeological finds show that several Maya groups lived here then. Their lands didn't match today's country borders.

Spain quickly sent explorers to Guatemala and Honduras. The conquest of Yucatán (a region north of Belize) began in 1527. The Maya fought hard against the Spanish. But diseases brought by the Spanish made many Maya sick and weak. This made it harder for them to resist. In the 1600s, Spanish missionaries built churches in Maya villages.

Pirates and Logwood Cutters

During this time, Piracy became common along the coast. In 1642 and 1648, pirates attacked Salamanca de Bacalar, a Spanish town in southern Yucatán. When Bacalar was abandoned, Spain lost control over the Maya areas of Chetumal and Dzuluinicob. Bacalar wasn't rebuilt until 1729.

Between 1638 and 1695, the Maya in Tipu lived freely from Spanish rule. But in 1696, Spanish soldiers used Tipu as a base to control the area. They also supported missionaries. In 1697, the Spanish conquered the Itzá Maya. In 1707, the Spanish forced the people of Tipu to move near Lake Petén Itzá. The Maya's political center in Dzuluinicob disappeared just as British settlers became more interested in the area.

Britain and Spain: A Rivalry for Control

In the 1500s and 1600s, Spain tried to control all trade and settlement in its New World colonies. But other European countries, like the Dutch, English, and French, wanted to trade and settle there too. They used smuggling, piracy, and war to challenge Spain's control.

In the early 1600s, English buccaneers (a type of pirate) started cutting logwood in southeastern Mexico and the Yucatán Peninsula. This wood was used to make a special dye for clothes. English buccaneers also used the coast as a base to attack Spanish ships. By the 1650s and 1660s, they stopped robbing Spanish logwood ships and started cutting their own wood. A treaty in 1667, which aimed to stop piracy, encouraged this change.

The first lasting British settlement in what is now Belize started in the late 1710s. This happened after the Spanish destroyed earlier British logging camps. Famous pirate Blackbeard even sailed in the Bay of Honduras in 1717–1718.

Britain and Spain kept fighting over Britain's right to cut logwood and settle in the region. Throughout the 1700s, Spain attacked the British settlers whenever they were at war. However, Spain never truly settled the area. The British always came back and expanded their trade. The 1763 Treaty of Paris allowed Britain to cut logwood but said Spain still owned the land. When war started again in 1779, the British settlement was left empty. The Treaty of Versailles in 1783 again allowed the British to cut logwood. By then, logwood trade was less important. Honduras Mahogany became the main export.

The British didn't want to set up a formal government. They feared it would anger the Spanish. But settlers started electing magistrates (local officials) to create their own laws as early as 1738. In 1765, these rules were written down as Burnaby's Code. When settlers returned in 1784, Colonel Edward Marcus Despard was made superintendent. He oversaw the Settlement of Belize. The 1786 Convention of London allowed British settlers to cut and export timber. But it said they couldn't build forts, set up a government, or start large farms. Spain still owned the land.

The last Spanish attack on the British settlement was the Battle of St. George's Caye. This happened in 1798. The British fought off the Spanish. This was Spain's last try to control the area.

Even though treaties banned local government and large farms, both grew. By the late 1700s, a small group of rich settlers controlled the area's economy. They owned most of the land and about half of all slaves. They also controlled trade and taxes. They elected magistrates from their own group, who made laws and acted as judges. These landowners didn't want anyone to challenge their power.

Things changed when the Spanish lands around Belize became independent countries: Mexico and the Federal Republic of Central America. In 1825, Britain officially recognized Mexico. In 1826, Mexico gave up its claims to Belize. Later, the local leaders in Belize made up a story about a Scottish buccaneer named Peter Wallace. They said he settled there in 1638 and gave his name to the Belize River. This story helped them claim a longer British history.

Slavery in Belize: 1794–1838

The first mention of African slaves in the British settlement was in 1724. A Spanish missionary said the British were bringing them from Jamaica, Bermuda, and other British colonies. A hundred years later, there were about 2,300 slaves. Most were born in Africa. Many kept their African cultures at first. But slowly, a new Kriol culture formed.

Slavery in Belize was mostly for cutting timber. Treaties didn't allow large farms. Settlers needed only a few slaves for logwood. But when they switched to mahogany in the late 1700s, they needed more money, land, and slaves for bigger operations. Other slaves worked as house helpers, sailors, blacksmiths, nurses, and bakers. Even though it was different from farm slavery, it was still very harsh. A report in 1820 said slaves often faced "extreme inhumanity." Many slaves escaped to Yucatán in the 1700s. In the early 1800s, many ran away to Guatemala and Honduras.

The small group of settlers kept control by dividing slaves from the growing number of free Kriol people. Free Kriols had some limited rights. But their economic activities and voting rights were restricted. Still, these limited rights made many free Black people show loyalty to British ways.

The law to end slavery in British colonies was passed in 1833. It aimed to make changes slowly over five years. It used a system called "apprenticeship" to keep masters in control of former slaves. Former slave owners were also paid for their loss of property. After 1838, the old masters still controlled the country for over a century. They did this by not letting freed people own land and limiting their economic freedom.

The Garifuna People Arrive

As slavery ended, a new group, the Garifuna, arrived. In the early 1800s, the Garifuna came to Belize. They were descendants of Caribs from the Lesser Antilles and Africans who had escaped slavery. The Garifuna had fought against British and French rule in the Lesser Antilles. But they were defeated by the British in 1796. After a big rebellion on Saint Vincent, the British moved between 1,700 and 5,000 Garifuna across the Caribbean. They went to the Bay Islands (now Islas de la Bahía) off Honduras. From there, they moved to the coasts of Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and southern Belize. By 1802, about 150 Garifuna had settled in the Stann Creek area (now Dangriga). They fished and farmed.

More Garifuna came to Belize after a civil war in Honduras in 1832. Many Garifuna men soon found work cutting mahogany alongside slaves. By 1841, Dangriga, the largest Garifuna settlement, was a busy village. An American traveler named John Stephens said Punta Gorda had 500 people and grew many fruits and vegetables.

The British saw the Garifuna as people who were settling on land without permission. In 1857, the British told the Garifuna they had to get leases from the government. If not, they could lose their land and homes. The 1872 Crown Lands Ordinance created special areas for the Garifuna and Maya. The British stopped both groups from owning land. They saw them as a source of cheap labor.

Changes in Government: 1850–1862

In the 1850s, a power struggle happened between the superintendent and the landowners. This, along with international events, led to big changes in government. In the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty of 1850, Britain and the United States agreed to help build a canal across Central America. They also agreed not to colonize any part of Central America. Britain said this only applied to future settlements. But the United States said Britain had to leave the area. This was especially true after 1853, when President Franklin Pierce's government emphasized the Monroe Doctrine. Britain gave up the Bay Islands and the Mosquito Coast in Nicaragua.

But in 1854, Britain created a formal government for its settlement in Belize. This new Legislative Assembly had eighteen elected members. Each had to own property worth at least £400. It also had three official members chosen by the superintendent. Only people with a certain income could vote. This made the legislature very limited. The superintendent could delay or close the assembly. He could also start new laws and approve or reject bills. This meant the legislature was more for talking than making decisions. The Colonial Office in London became the real power. This shift became stronger in 1862. The Settlement of Belize was declared a British colony called British Honduras. The British representative was made a lieutenant governor, under the governor of Jamaica.

The Clayton–Bulwer Treaty of 1850 said neither the US nor Britain should control or colonize Central America. It was unclear if this included Belize. In 1853, a new American government tried to make Britain leave Belize. In 1856, the Dallas-Clarendon Treaty recognized Belize as British territory. The Sarstoon River was set as the southern border with Guatemala. The Anglo-Guatemalan Treaty of 1859 set the western border. This temporarily settled Guatemala's claim. Only the northern border with Mexico was still undecided.

British Honduras: 1862–1981

As the British settled more and went deeper into the country for mahogany, the Maya resisted. But in the second half of the 1800s, things changed for the Maya. During the Caste War in Yucatán (1847-1855), thousands of refugees fled to British Honduras. Many were small farmers. Even though the Maya weren't allowed to own land, they grew a lot of crops by the mid-1800s.

Maya Resistance and New Settlements

In 1866, a Maya group led by Marcos Canul attacked a mahogany camp. British troops sent to San Pedro were defeated by the Maya later that year. In early 1867, British troops destroyed Maya villages to drive them out. But the Maya returned. In April 1870, Canul and his men took over Corozal. An attack by the Maya on Orange Walk in 1872 was the last serious attack on the British colony.

In the 1880s and 1890s, Mopan and Kekchí Maya escaped forced labor in Guatemala. They settled in villages in southern British Honduras. The British used a system called "indirect rule" with elected alcaldes (mayors). This linked the Maya to the colonial government. But because their settlements were far away, the Mopan and Kekchí Maya didn't become as much a part of the colony as the Maya in the north. In the north, a Mestizo culture (mixed Maya and Spanish) grew. By the end of the 1800s, the different ethnic groups were set:

- Protestants, mostly of African descent, speaking English or Creole, living in Belize Town.

- Roman Catholic Maya and Mestizos, speaking Spanish, living mainly in the north and west.

- Roman Catholic Garifuna, speaking English, Spanish, or Garifuna, settled on the southern coast.

The Colony Takes Shape: 1862–1871

The military trips against the Maya were expensive. This increased the costs of running the new colony of British Honduras. At the same time, the economy was very bad. Rich landowners and merchants controlled the Legislative Assembly. This assembly managed the colony's money. Some landowners were also involved in trade, but their interests were different from other merchants in Belize Town. Landowners didn't want land taxes and wanted higher import taxes. Merchants wanted the opposite.

Also, the town merchants felt safe from Maya attacks. They didn't want to pay to protect mahogany camps. Landowners felt they shouldn't pay taxes if their lands weren't protected. These disagreements stopped the Legislative Assembly from raising enough money. Since they couldn't agree, the members of the Legislative Assembly gave up their power. They asked for direct British rule. They wanted the greater security of being a "crown colony". The new government started in April 1871. The new law-making body became the Legislative Council.

Since 1854, the richest people had elected an Assembly. This was replaced in 1962 by a Legislative Council chosen by the British monarchy.

Under the new 1871 government, the lieutenant governor and the Legislative Council ruled British Honduras. The Council had five "official" members (government workers) and four "unofficial" members (chosen by the governor). This change meant that power shifted from the old local leaders to British companies and the Colonial Office in London.

Life Under Colonial Rule: 1871–1931

The timber industry controlled most of the land. It also had a lot of say in colonial decisions. This slowed down the growth of farming and other types of businesses. Even though British Honduras had huge areas of empty land, a small group of Europeans owned most of it. This stopped former slaves from becoming landowners. However, there were exceptions, like Isaiah Emmanuel Morter, who was the son of former slaves and owned large banana and coconut farms.

Land ownership became even more concentrated during the economic downturn in the mid-1800s. This led to the decline of the old settler class. It also meant more money was controlled by fewer people, and British land ownership grew. The British Honduras Company (later the Belize Estate and Produce Company) became the biggest landowner. It owned about half of all private land in the colony. This new company was the main power in British Honduras's economy for over a century.

This meant that decisions about the colony's economy were mostly made in London. It also signaled the end of the old local elite. By about 1890, most trade in British Honduras was controlled by a small group of Scottish and German merchants, many of whom were new to the area. This European minority had a lot of power in the colony's politics. This was partly because they were guaranteed spots on the Legislative Council. In 1892, the governor appointed some Creole members, but white members were still the majority.

The colony's economy and society were mostly stagnant for many years before the 1930s. But changes were slowly happening. The mahogany trade was still slow. Attempts to start large farms failed. The timber industry had a short boost in the early 1900s because the United States needed more forest products. Exports of chicle, a gum from the sapodilla tree used for chewing gum, helped the economy from the 1880s. There was a brief boom in mahogany around 1900 due to US demand. But cutting trees without replanting them quickly used up the resources.

Creoles who had connections with businesses in the United States started to challenge the old ties with Britain. This was because trade with the US grew stronger. In 1927, Creole merchants and professionals replaced the British landowners' representatives on the Legislative Council. This showed that social changes were happening, even though the economy was slow.

An agreement between Mexico and Britain in 1893 set the border along the Rio Hondo. The treaty was finalized in 1897.

The Start of Modern Politics: 1931–1954

The Great Depression badly hurt the colony's economy. Unemployment rose quickly. On top of this, the worst hurricane in recent history hit Belize Town on 10 September 1931. More than 1,000 people died. The British help was slow and not enough. The British government used this chance to control the colony more tightly. They gave the governor power to make laws in emergencies. The Belize Estate and Produce Company survived the depression because of its special connections in British Honduras and London.

Meanwhile, workers in mahogany camps were treated almost like slaves. A law from 1883, the Masters and Servants Act, made it a crime for a worker to break a contract. In 1931, Governor Sir John Burdon said no to ideas for legalizing trade unions, setting a minimum wage, or having sickness insurance.

The poor people responded in 1934 with protests, strikes, and riots. This marked the beginning of modern politics and the independence movement. Riots had happened before. But the events of the 1930s were different. They led to groups with clear goals for workers and politics. Antonio Soberanis Gómez and his group, the Labourers and Unemployed Association (LUA), criticized the governor, rich merchants, and the Belize Estate and Produce Company. They used strong words that helped create a new nationalistic and democratic political culture.

The labor protests quickly led to relief work. The governor saw this as a way to avoid more unrest. But the biggest achievements were the labor reforms passed between 1941 and 1943. Trade unions became legal in 1941. A 1943 law removed breaking a labor contract from the criminal code. The General Workers' Union (GWU), started in 1943, quickly grew across the country. It gave important support to The Nationalist Movement (Belize) that began with the formation of the People's United Party (PUP) in 1950.

So, the 1930s were a key time for Belizean politics. It was when old ways of unfair labor and colonial rule started to change. New labor and political groups and systems began. During this time, more people could vote. In 1945, only 822 voters were registered out of over 63,000 people. But by 1954, all adults who could read could vote in British Honduras. Credit unions and cooperatives started after 1942, thanks to the work of Fr. Marion M. Ganey S.J. This slowly increased the economic and political power of the Maya and poorer people.

In December 1949, the governor lowered the value of the British Honduras dollar. He did this against the wishes of the Legislative Council. This act started Belize's independence movement. The governor's action angered nationalists. It showed how limited the legislature was and how much power the colonial government had. The devaluation also angered workers. It protected big international companies but made goods more expensive for working people. So, the devaluation brought together workers, nationalists, and the middle class against the colonial government. The night the governor announced the devaluation, the People's Committee was formed. The independence movement quickly grew stronger.

Between 1950 and 1954, the PUP, formed after the People's Committee ended on 29 September 1950, grew its organization. It built its support among the people and stated its main goals. By January 1950, the GWU and the People's Committee held public meetings together. They talked about devaluation, labor laws, the idea of a West Indies Federation, and government reform. However, as political leaders took control of the union in the 1950s to use its power, the union movement itself became weaker.

The PUP focused on pushing for government reforms. These included:

- All adults being able to vote, even if they couldn't read.

- A Legislative Council where all members were elected.

- An Executive Council chosen by the leader of the party with the most votes.

- A system with ministers (like government departments).

- Ending the governor's special powers.

In short, the PUP wanted a government that truly represented the people and was responsible to them.

The colonial government, worried about the PUP's growing support, tried to attack the party. They targeted two of the PUP's main public platforms: the Belize City Council and the PUP itself. In 1952, George Price easily won the Belize City Council elections. In just two years, despite problems and disagreements, the PUP became a powerful political force. George Price clearly became the party's leader.

The colonial government and the National Party (made of loyal members of the Legislative Council) tried to say the PUP was pro-Guatemalan or even communist. But the PUP leaders saw British Honduras as belonging to neither Britain nor Guatemala. The governor and the National Party failed to make the PUP look bad because of its contacts with Guatemala. At that time, Guatemala was led by the democratic government of President Jacobo Arbenz.

When people voted on 28 April 1954, in the first election where all literate adults could vote, the main issue was clear: colonialism. A vote for the PUP was a vote for self-government. Almost 70 percent of voters participated. The PUP won 66.3 percent of the votes and took eight of the nine elected seats in the new Legislative Assembly. More government reform was definitely going to happen.

Becoming Independent: The Border Dispute with Guatemala

British Honduras faced two main challenges to becoming independent: 1. Britain was slow to let its citizens govern themselves until the early 1960s. 2. Guatemala had a long-standing claim to all of Belize. Guatemala had often threatened to use force to take over British Honduras.

By 1961, Britain was ready to let the colony become independent. Talks between Britain and Guatemala started again in 1961. But the elected leaders of British Honduras had no say in these talks. George Price refused an offer to make British Honduras an "associated state" of Guatemala. He repeated his goal of leading the colony to full independence.

In 1963, Guatemala stopped talks and ended diplomatic relations with Britain. Talks between Guatemala and British Honduras started and stopped many times in the late 1960s and early 1970s. From 1964, Britain only controlled Belize's defense, foreign affairs, internal security, and public service rules. In 1973, the colony's name was changed to Belize, getting ready for independence.

By 1975, the Belizean and British governments were tired of dealing with Guatemala's military governments. They agreed on a new plan: take Belize's case for self-determination to international groups. The Belize government felt that getting international support would make its position stronger. It would weaken Guatemala's claims and make it harder for Britain to give in. Belize argued that Guatemala was stopping its rightful wish for independence. Belize said Guatemala was pushing an old claim and hiding its own desire to colonize by saying it was trying to get back land lost to a colonial power.

Between 1975 and 1981, Belizean leaders presented their case for self-determination at meetings of the Commonwealth of Nations, the Nonaligned Movement, and the United Nations (UN). At first, Latin American governments supported Guatemala. But between 1975 and 1979, Belize gained the support of Cuba, Mexico, Panama, and Nicaragua. Finally, in November 1980, with Guatemala completely alone, the UN passed a resolution demanding Belize's independence.

A final attempt was made to reach an agreement with Guatemala before Belize became independent. The Belizean representatives in the talks made no compromises. A proposal, called the Heads of Agreement, was signed on 11 March 1981. However, extreme political groups in Guatemala called the agreement a sellout. The Guatemalan government refused to approve it and left the talks. Meanwhile, the opposition in Belize held violent protests against the Heads of Agreement. A state of emergency was declared. But the opposition had no real other plans. With independence celebrations coming, the opposition's spirits fell. Belize became independent on 21 September 1981, after the Belize Act 1981, without reaching a full agreement with Guatemala.

Independence: Belize Today

With George Price as leader, the PUP won all elections until 1984. In that election, the first national election after independence, the PUP lost to the United Democratic Party (UDP). UDP leader Manuel Esquivel became prime minister instead of Price. Price returned to power after elections in 1989.

Guatemala's president officially recognized Belize's independence in 1992. The next year, the United Kingdom said it would end its military presence in Belize. All British soldiers left in 1994, except for a small group who stayed to train Belizean troops.

The UDP won power again in the 1993 national election. Esquivel became prime minister for a second time. Soon after, Esquivel announced he was stopping a deal made with Guatemala during Price's time. He claimed Price had given too many concessions to get Guatemala's recognition. This deal would have solved the 130-year-old border dispute. Border tensions continued into the early 2000s, even though the two countries worked together in other areas.

The PUP won a huge victory in the 1998 national elections. PUP leader Said Musa became prime minister. In the 2003 elections, the PUP kept its majority, and Musa continued as prime minister. He promised to improve conditions in the less developed southern part of Belize.

In 2005, Belize had unrest because people were unhappy with the People's United Party government. This included tax increases in the national budget. On 8 February 2008, Dean Barrow of the United Democratic Party (UDP) became Belize's first Black prime minister.

Throughout Belize's history, Guatemala has claimed ownership of all or part of the territory. This claim sometimes appears on maps showing Belize as Guatemala's twenty-third province. As of March 2007, the border dispute with Guatemala is still not solved and is quite sensitive. At different times, the United Kingdom, Caribbean Community leaders, the Organisation of American States, and the United States have had to help mediate. In December 2008, Belize and Guatemala signed an agreement to take their border issues to the International Court of Justice. This would happen after referendums in both countries (which had not taken place as of March 2019). Both Guatemala and Belize are working on measures approved by the OAS, like the Guatemala-Belize Language Exchange Project.

Since independence, a British garrison (military base) has stayed in Belize at the request of the Belizean government.

The Conservative United Democratic Party led Belize for 12 years under Prime Minister Dean Barrow. But in the general election in November 2020, the opposition center-left PUP party won. The leader of the People’s United Party (PUP), Johnny Briceño, who was a former deputy prime minister, became the new Prime Minister of Belize on 13 November 2020.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Belice para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Belice para niños

- History of the British West Indies

- History of Central America

- History of the Caribbean

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Postage stamps and postal history of Belize

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |