History of Cologne facts for kids

The History of Cologne spans over 2000 years, making it a very old city! In the year 50 AD, Cologne became an official Roman city called "Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium." Later, under Frankish rule, it became known as Cologne. Because it was located right on the Rhine river, Cologne grew into an important trading hub in the early Middle Ages. Merchants from Cologne controlled goods moving from northern Italy all the way to England. The archbishops, who were powerful church leaders, helped make Cologne known as "Holy Cologne." They built a large city wall and the famous Gothic Cologne Cathedral to show their power.

In the 1400s, Cologne gained independence from the archbishops and became a Free Imperial City. This meant the citizens had more control, and the city became very grand, known for its art like the Cologne School of Painting. After the Thirty Years' War, Cologne's growth slowed down. But when it became part of Prussia in 1815, the city grew rapidly thanks to industrialization. The Cologne Cathedral was finally finished in 1880, becoming a symbol of German unity and the city's most famous landmark.

During World War II, Cologne was heavily damaged. The city spent decades rebuilding to restore its beautiful look on the Rhine. Today, Cologne is Germany's fourth-largest city with over a million people. It's famous for events, especially the lively Cologne Carnival, which attracts many tourists.

Contents

- How Cologne Grew

- Early History

- Cologne in the Holy Roman Empire

- Cologne as a Free Imperial City

- Trade with England

- Emperors and Kings Visit

- City Leaders and Changes

- Cathedral Work Stops

- Silk Production in Cologne

- Rich Families Show Off

- Books Printed in Cologne

- Religious Debates

- Efforts to Avoid Religious Conflict

- Trade Routes to Flanders

- Renaissance in Cologne

- Efforts for Cologne's Trade

- Royal Coronations Move to Frankfurt

- Managing the Rhine River

- City Maps for Administration

- Failed Peace Efforts

- Early Modern Period

- Modern History

- See also

How Cologne Grew

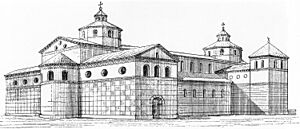

In ancient Roman times, cities like Trier and Cologne were important centers in Europe. Cologne was special because five Roman roads met there, and the Rhine river was a major transport route. After the Roman Empire declined, many towns disappeared, but Cologne, Trier, and Mainz continued to be inhabited, though with fewer people. Around the year 700, Cologne had about 3,000 residents.

Over the next few centuries, Cologne grew a lot because of its busy trade on the Rhine and because it became the home of an important archbishop. By the year 1000, Cologne had 10,000 people, making it one of the largest cities in northwestern Europe. Between 1000 and 1200, its population quadrupled to 40,000! This growth led to many churches being built in the Romanesque style.

For a long time, Cologne was one of the 30 biggest cities in Western Europe. This shows how important it was as a trading center. Around 1200, with 40,000 people, Cologne was as big as London and Paris, ranking among the top 10 cities in Western Europe.

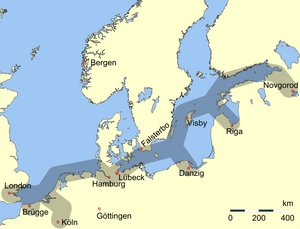

Cologne's merchants built a strong trading network that connected to cities all over Europe, from the Hanseatic towns in the Baltic Sea to London, Bruges, Milan, and Venice. However, Cologne's population stayed around 45,000 until the late 1700s, while other cities like Ghent, Paris, and Milan grew much larger.

By the end of the 1400s, when Cologne became a Free Imperial City, it was the largest city in the Holy Roman Empire. But trade routes started shifting away from the Rhine to sea routes in the mid-1500s, which made Cologne less important in long-distance trade. Still, Cologne managed to keep its population of around 40,000 until the 1700s, even through wars and diseases.

The Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) actually helped Cologne because it was seen as a safe city and benefited from selling weapons. However, Cologne didn't join the new Atlantic trade routes that made cities like Amsterdam and Hamburg very rich. By 1700, Cologne was no longer among the top 30 largest cities in Western Europe.

With the start of the Industrial Revolution, Cologne's population doubled from 45,000 in 1810 to 90,000 in 1846. By 1850, it was the sixth-largest city in Central Europe. The city continued to grow, reaching 650,000 people by World War I. After the war, it was one of the four largest cities in Germany. Even after the massive destruction of World War II, Cologne recovered and grew to over a million inhabitants by 2000, becoming Germany's fourth-largest city.

Early History

Roman Times

Around 39 BC, a Germanic tribe called the Ubii made a deal with the Romans and settled on the left bank of the Rhine. Their main settlement, Oppidum Ubiorum, was also an important Roman military base. In 50 AD, Agrippina the Younger, who was born in Cologne and was the wife of Emperor Claudius, asked for her hometown to become a colonia. This meant it would be a city under Roman law. It was then renamed Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensis.

In 80 AD, the Eifel Aqueduct was built. This was one of the longest aqueducts in the Roman Empire, bringing 20,000 cubic meters of water to the city every day! Ten years later, Cologne became the capital of the Roman province of Lower Germany, Germania Inferior.

In 260 AD, Postumus made Cologne the capital of the Gallic Empire, which was a separate empire for a short time. By the 3rd century, about 20,000 people lived in and around the town. In 310 AD, Emperor Constantine I built a bridge over the Rhine, protected by a fort called castellum Divitia. This fort later became part of Cologne and is now known as Deutz.

The presence of Jews in Cologne was first recorded in 321 AD. The Jewish community in Cologne claims to be the oldest north of the Alps. Emperor Constantine even allowed Jews to be elected to the City Council.

Frankish Rule

The Franks attacked and looted Cologne several times in the 4th century. In 355 AD, the Alemanni tribes besieged the town for 10 months before taking and plundering it. The Romans, led by Julian, took the city back a few months later. However, Cologne finally fell to the Ripuarian Franks in 462 AD.

Cologne became a base for the Carolingians to spread Christianity to the Saxons and Frisians. In 795, Charlemagne's chaplain, Hildebold, became the first archbishop of Cologne. After Charlemagne's death, Cologne became part of Middle Francia. In 873, Archbishop Wilbert consecrated the "Old Cathedral," which was the building before the current Cologne Cathedral. In 876, Cologne became part of East Francia. The city was burned down by Vikings in the winter of 881/882.

In the early 900s, Cologne became a permanent part of the Holy Roman Empire (and eventually Germany).

Cologne in the Holy Roman Empire

Later Middle Ages

Cologne's first Christian bishop was Maternus, who helped build the first cathedral in the early 4th century. In 794, Hildebald was the first Bishop of Cologne to be made an archbishop. Bruno I (925–965), the younger brother of Emperor Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, founded several monasteries in the city.

The archbishops of Cologne became very powerful, advising emperors and even holding the office of Arch-Chancellor of Italy from 1031. Their power reached its peak under Archbishop Engelbert II of Berg, who fought to establish the archdiocese of Cologne as both a church authority and a secular territory. He was murdered in 1225.

Construction of the famous Gothic cathedral began in 1248 under Konrad von Hochstaden. The eastern part was finished and consecrated in 1322. Work on the western part stopped in 1475 and wasn't finished until 1880.

In 1074, the city formed a commune, giving citizens more say. By the 1200s, the relationship between the city and its archbishop became difficult. After the Battle of Worringen in 1288, the citizens of Cologne captured Archbishop Siegfried of Westerburg. This led to the city gaining almost complete freedom. The archbishop had to recognize Cologne's political independence, though he kept some rights, like administering justice.

Long-distance trade in the Baltic Sea became very active as major trading towns joined the Hanseatic League, led by Lübeck. This League was a business alliance of trading cities that controlled trade in Northern Europe from the 1200s to the 1500s. Cologne was a leading member, especially because of its trade with England. The Hanseatic League gave merchants special rights in member cities. Cologne's central location on the Rhine, connecting major trade routes, was key to its growth. Its economy relied on its large harbor, its role as a transport hub, and its skilled merchants who built connections with other Hanseatic cities.

Cologne became a free city after 1288, and in 1475, it was officially made a free imperial city. This status lasted until France took it over in 1796. The Archbishopric of Cologne was a state itself, but the city of Cologne was independent. The archbishops usually lived in Bonn or Brühl because they weren't allowed to enter the city.

The Cologne Cathedral held sacred relics, making it a popular destination for pilgrims. With the bishop living outside, the city was run by wealthy merchants called patricians. Craftsmen formed guilds, which were groups that controlled different trades. Society was divided into clear classes: clergy, doctors, merchants, and various artisan guilds. Poor people could not be full citizens. There were often arguments about taxes, public spending, business rules, and how much control the guilds had.

The first attack against the Jews of Cologne happened in 1349, when they were blamed for the Black Death. In 1424, they were forced to leave the city. They were allowed back in 1798.

Cologne as a Free Imperial City

Trade with England

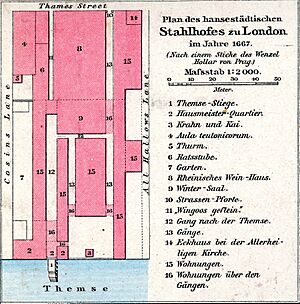

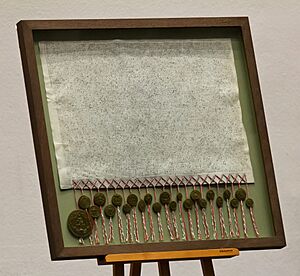

A very important trading post for Cologne was the Steelyard (Stalhof) in London. This special trading center, with its unique rights, allowed Cologne merchants to control English trade along the Rhine. The importance of the Steelyard even led to the Anglo-Hanseatic War in 1469. Cologne stayed neutral during this war because of its special relationship with London. It was even kicked out of the Hanseatic League in 1471! But after the League won the war, Cologne was let back in, and its old trading rights were renewed.

Trade with England remained very important for Cologne until the mid-1500s. Cologne merchants were especially good at selling English tin and dominating the trade of weapons like swords and armor. Cologne thrived as a merchant city, controlling the flow of goods across the Rhine from London to Italy, and connecting to east-west trade routes to Frankfurt and Leipzig. Cologne merchants could be found in all major European trading centers. The importance of Cologne's trade was also shown when the Cologne Mark became the official currency standard for the Holy Roman Empire in 1524.

Emperors and Kings Visit

Between 1484 and 1531, emperors and kings often visited Cologne. This brought the city's wealthy families closer to the powerful House of Habsburg. For example, in 1484, Maximilian of Austria was crowned German king in Cologne, making the city feel like a Habsburg capital. He even appointed a Cologne merchant, Nicasius Hackeney, as his chief financial advisor.

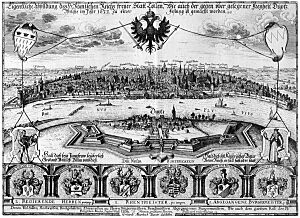

The Imperial Diet (a big meeting of rulers) was held in Cologne in 1505, which was a highlight of Maximilian's rule. Another diet finished in Cologne in 1512. When Charles V was crowned Roman-German king in 1520 and Ferdinand I in 1531, the ceremonies involved the Cologne archbishop and a grand procession to Cologne to honor the Shrine of the Three Kings in the Cologne Cathedral. The final celebrations were held with great splendor in Cologne. For the 1531 celebration, the Cologne Council even had a detailed city map made by Anton Woensam to show off Cologne's greatness to the new king.

City Leaders and Changes

After Cologne became a Free Imperial City in 1475, it faced big financial problems. Wealthy merchants, who were also the city's main lenders, controlled the council. They tried to solve the money problems by raising taxes on food and wine, which made many citizens unhappy.

A small group of very rich families, known as the Cologne patricians, dominated the city council. This led to a system where corruption and favoritism, known as "Kölscher Klüngel" (Cologne cronyism), became common. A secret group of councilmen, called krensgin, made most important decisions without consulting others. This lack of transparency and high taxes caused ongoing disputes.

In 1481, Werner von Lyskirchen tried to lead a revolt, but it was quickly stopped, and he was executed. The powerful families remained in control. However, in 1512, a riot broke out, and citizens organized in guilds took power. Ten former councilmen were punished, and new elections were held. New rules were written in December 1513, called the "Transfixbrief," to prevent corruption and protect citizens' rights, including their personal freedom and homes.

Cathedral Work Stops

In 1474, when Cologne needed to prepare for war against the Duke of Burgundy, construction on the Cologne Cathedral had to stop. The craftsmen were needed to strengthen the city's defenses. After the war, Archbishop Hermann IV of Hesse didn't continue building for about 30 years because the church was deeply in debt. He used donations to fix the church's finances.

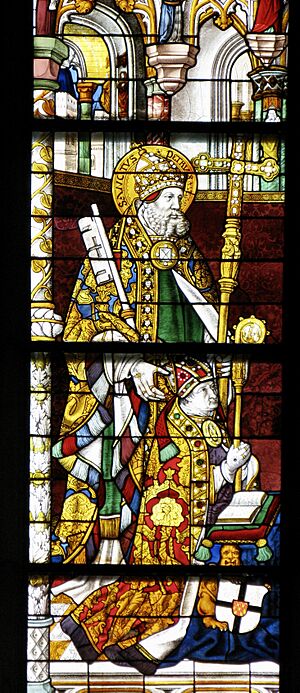

It wasn't until his successor, Archbishop Philip II of Daun-Oberstein, that work on the cathedral restarted. Beautiful late Gothic stained glass windows were installed in 1508, designed by famous artists from the Cologne School of Painting. However, regular construction stopped again after 1525 because a major way of funding, selling indulgences, dried up due to the Reformation. By 1560, cathedral construction completely stopped and didn't resume until 1823!

Silk Production in Cologne

Silk production had been important in Cologne since the early Middle Ages. It reached its peak in the mid-1500s. Cologne, along with Paris, was one of the biggest silk production centers north of the Alps. Around 1500, silk cloth was probably Cologne's most successful export.

The silk business was controlled by the Silk Office (Seidenamt), a guild where mostly women worked. This was unusual and allowed many female guild masters to become very wealthy. For daughters of wealthy families, working in the silk business was a respected career. The most famous female silk entrepreneur was Fygen Lutzenkirchen, who was one of Cologne's richest citizens around 1498.

Silk production depended on importing raw silk from northern Italy, usually through Venice and Milan. The weaving and crafting of silk were often done by women working from home, with wholesalers providing the raw materials. Cologne's silk products were mainly sold to the local clergy and exported to cities like Frankfurt, Strasbourg, and Leipzig. By 1560, Cologne had 60 to 70 silk merchants who processed 700 bales of silk each year.

Rich Families Show Off

From the late 1400s, Cologne's wealthy families wanted to show off their status. They became generous donors, ordering large altarpieces and funding entire chapels or church decorations. This is why, by the late 1700s, Cologne had "more medieval works of art than anywhere else in the world."

Some families built grand homes in the city. Nicasius Hackeney, who was close to Emperor Maximilian, built the Hackeney'schen Hof around 1505, which the emperor also used as a city palace. Johann Rinck, from a family of influential merchants, built the Rinkenhof at the same time. These palaces had tall, polygonal stair towers, which became a symbol of importance.

The building of chapels was not just for showing off, but also to help the donors' souls. In 1493, Mayor Johann von Hirtz donated a chapel in St. Maria im Kapitol. In 1510, Johannes Hardenrath and his wife funded the New Sacristy at the Kartäuserkirche (Carthusian Church) St. Barbara, which features beautiful late Gothic architecture.

The demand for impressive art benefited the many artists of the Cologne School of Painting. Famous painters like the Master of the Holy Kinship and the Master of the Saint Bartholomew Altarpiece created large altarpieces in the unique Cologne style. The beautiful rood screen in St. Pantaleon Church, created around 1502, shows the amazing skill of Cologne's late Gothic sculptors.

Books Printed in Cologne

The new technology of letterpress printing quickly came to Cologne. As early as 1464, Ulrich Zell printed the first book. By the end of the 1400s, Cologne had 20 printing presses, producing over 1200 different books. This made Cologne one of Europe's leading book printing centers, after Venice, Paris, and Rome. Families involved in printing, like the Quentel, Birckmann, and Gymnich, became very successful.

Peter Quentel, a busy printer, was even elected as a Cologne councilman for many years. In 1524, he published a Low German version of Luther's New Testament. However, from the late 1520s, the Cologne Council banned the printing of Lutheran books. Peter Quentel then published the first complete German translation of the Bible by Johann Dietenberger, which became an important Catholic version.

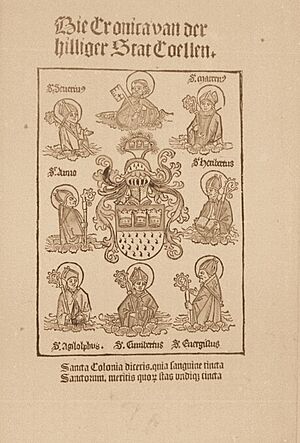

Cologne became a top place for printing Latin works, especially religious, scientific, and humanist books. It was a leading center for publishing the writings of the humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam. Cologne was also the only major imperial city to remain Catholic, so it offered many books supporting the Counter-Reformation in Latin. The most famous book from Cologne's printing industry is the Koelhoff Chronicle, published in 1499. Written in the local Cologne dialect, it's considered a highlight of late medieval Cologne city history.

Religious Debates

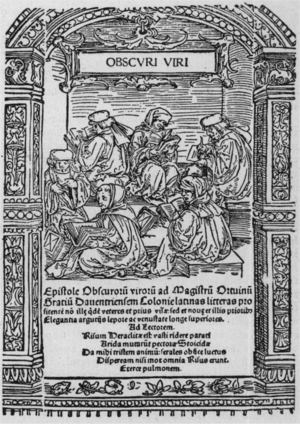

In the early 1500s, a big debate spread from Cologne across the empire: should Jewish books, especially the Talmud, be confiscated and burned to suppress the Jewish faith? This anti-Jewish movement was led by Johannes Pfefferkorn, a Jewish convert to Catholic Christianity, supported by the Cologne Dominican Order. The Dominican theologian Jacob van Hoogstraaten, a papal inquisitor, published opinions and pamphlets against Johannes Reuchlin, a leading humanist who defended Jewish texts. This anti-Jewish view was also shown in the Cologne Cathedral through stone reliefs donated by Victor von Carben, a former Jew, illustrating the change from Judaism to Christianity.

This controversy involved many Humanists and Emperor Maximilian. Van Hoogstraaten and the Cologne University were ridiculed in the "Letters of Obscure Men" written by humanists, which made Cologne's conservative theology look bad for decades. The debate eventually faded with the start of the Reformation.

Efforts to Avoid Religious Conflict

Martin Luther's ideas caused ongoing debates in Cologne about church reform. In 1520, during the coronation of Emperor Charles V, Luther's writings were publicly burned in the cathedral courtyard as heresy. In 1527, the city council decided to ban all Lutherans from the city, but they also claimed to seek reconciliation.

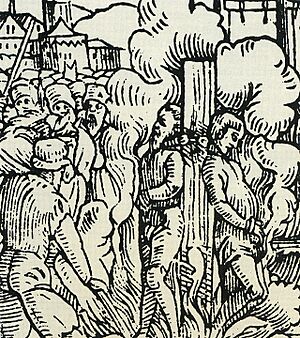

People who openly supported Reformation ideas, like preachers Adolf Clarenbach and Peter Fliesteden, were handed over by the council to the archbishop's authority. Archbishop Hermann V. von Wied sentenced them to death by burning at the stake. However, Hermann, who disliked church corruption, later tried to reform the Archbishopric. He even invited reform theologians Martin Bucer and Philipp Melanchthon to Cologne, who wrote a paper called "Simple-minded Apprehension" for him.

The Catholic leaders in the archdiocese and Cologne city council became suspicious of Hermann. In 1547, Emperor Charles V forced the archbishop to resign. This attempt to bridge the religious divide failed. The next archbishops, Adolf and Anton of Schaumburg, brought the archbishopric back to a strict Catholic path.

Trade Routes to Flanders

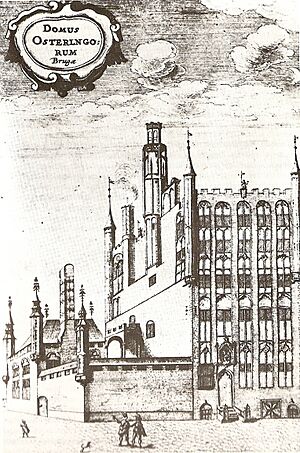

Trade with Flanders and the North Sea was very important for Cologne. In the 1500s, trade shifted from Bruges to Antwerp, which became Europe's economic center. By 1526, Antwerp had more people than Cologne, and by 1560, its population had doubled. Meanwhile, the importance of the Hanseatic trading post in Bruges declined because its harbor became too shallow for large ships.

Antwerp benefited from overseas trade, becoming a hub for imports like sugar and pepper. The Hanseatic League moved its trading post to Antwerp in 1545. Cologne merchants found it harder to compete. To avoid religious unrest, Portuguese, Italian, and Flemish merchants even settled directly in Cologne, importing goods like grain, furs, cloth, and silk, which competed with Cologne's own products. At times, these non-Cologne merchants handled a third of Cologne's long-distance trade.

Renaissance in Cologne

In the 1500s, Cologne's wealthy families started to bring Renaissance art styles they saw on their trade journeys, especially in Flanders, into their own commissions. In 1517, several Cologne families donated a rood screen (a screen separating the altar from the nave) for St. Maria im Kapitol. This elaborate work was ordered from an artist in Mechelen, introducing the Flemish Renaissance style to Cologne.

The extension of the town hall, called Löwenhof (Lion's Courtyard), was built in 1540, mixing late Gothic and Renaissance styles. Cornelis Floris, from Antwerp, was hired in 1561 to create the epitaphs (memorials) for two archbishops in the Cologne Cathedral. His style became known as the Floris style in Cologne. Floris also designed the city hall loggia, built from 1567. The most sought-after Cologne Renaissance painter was Barthel Bruyn the Elder, who developed his own style for portraits. Wealthy families sometimes even hired the royal court painter Hans Holbein the Younger in London to paint their portraits.

-

Floris style: epitaph in Cologne Cathedral

Efforts for Cologne's Trade

By the 1550s, it was clear that international trade was changing. Old trading posts with special rights were losing their power as new overseas routes were discovered, shifting long-distance trade away from the Rhine to the North Sea. Antwerp became Europe's economic center, growing to over 100,000 people by 1560, and outcompeting Cologne.

Cologne's wealthy merchants, who controlled the city council, tried to strengthen Cologne's position. In 1553, they founded the Cologne commodity exchange, inspired by Antwerp, to allow trading of commodity contracts. The bill of exchange business also grew in Cologne. To boost its traditional wine and cloth trades, Cologne became very involved in the Hanseatic League. In 1556, they created the role of a syndic (like a secretary-general) and gave it to Heinrich Sudermann of Cologne. He tried to use diplomacy to keep the old trading rights, but after Elizabeth I became queen of England in 1558, she didn't continue the privileges for the Stalhof in London.

After the Hanseatic trading post in Flanders moved to Antwerp, Sudermann tried to make it more important, but without much success. More successful was the Cologne Council's initiative to strengthen trade on the Rhine by building a new stacking house (Stapelhaus) from 1558 to 1561. This building helped handle the fish trade more effectively, and Cologne still benefited greatly from its Stapelrecht (staple right), which forced merchants to offer their goods for sale in the city.

Royal Coronations Move to Frankfurt

Maximilian II was crowned German king in November 1562 in Frankfurt am Main, not in Aachen as his ancestors had been for centuries. This meant the traditional procession from Aachen to Cologne to visit the Shrine of the Three Kings was skipped. The king no longer paid homage to the Magi in Cologne. The coronation festivities, which had brought Cologne close to the imperial power for centuries, were now held in Frankfurt.

This was a setback for Cologne. It happened because Archbishop Frederick IV of Wied had not yet been officially confirmed by the Pope at the time of the coronation. Also, the great leaders of the Empire avoided the long journey to Aachen and Cologne in autumn. The king also favored Protestant ideas and found relic homages outdated. All future imperial coronations also took place in Frankfurt, with the archbishop of Mainz becoming the coronator. This change hurt the long-standing idea of "Holy Cologne." Not surprisingly, from 1567, Cologne councilors built a new city hall loggia in Renaissance style, deliberately recalling Roman triumphal arches to remind people of Cologne's historical greatness.

Managing the Rhine River

Since the Middle Ages, people in Cologne had worried that the Rhine river was shifting its course on the right bank near Poll. Floods and ice flows made this worse. To prevent the Rhine from breaking through between Poll and Deutz, Cologne planned to strengthen the bank with structures called “Poll Heads.” It took until 1557 for the council and the archbishop to agree on these measures.

The large project started in 1560 and continued for over 250 years. Three heavy headlands were built as shore fortifications. Hundreds of ships were sunk, and willow trees and groynes (structures built out into the water) were used to prevent the river from changing course. Iron-reinforced oak logs, weighted with basalt boulders and connected by heavy crossbeams, were driven into the river bottom. The northern headland was said to be 1500 meters long.

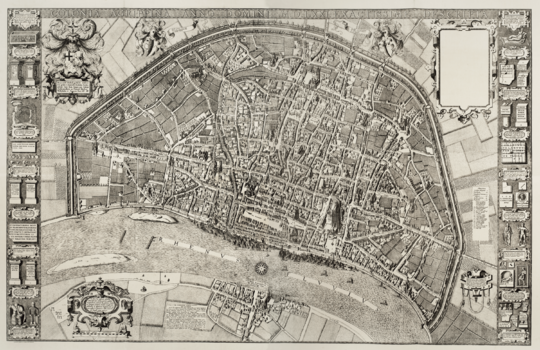

City Maps for Administration

The religious and economic unrest in the Spanish Netherlands from 1566 onwards worried Cologne. The Spanish general Duke of Alba was sent to Brussels in 1567 to stop the Flemish unrest with harsh military force. Many refugees left Antwerp and settled in Cologne, including Jan Rubens, father of the famous painter Peter Paul, and Anna of Saxony, wife of William of Orange. Duke Alba pressured Cologne to keep refugees out and to secure military routes to Spanish territories.

The Cologne Council tried to meet Spanish demands for better city administration and a strict approach to refugees. As a modern administrative step, the council had a detailed Bird's-eye view map of the city drawn to better track residents and immigrants. The cartographer Arnold Mercator created the map at a scale of 1:2450, aiming for scientific accuracy. It was based on a precise survey of the city's layout and showed buildings in a way that created a spatial effect. This "Mercator Plan" is considered the first reliable city plan of Cologne and one of the first accurate city maps ever made.

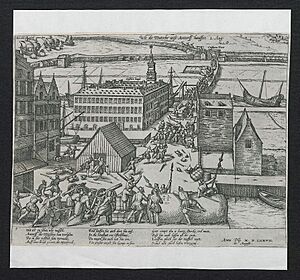

Failed Peace Efforts

The Spanish Netherlands, which was so important for Cologne's economy, remained unstable in the 1570s. In 1575, the Spanish king Philipp II went bankrupt, and his troops in the Netherlands were not paid. In 1576, they looted Antwerp, causing widespread horror known as the Spanish Fury. This strengthened the resistance of the Flemings and Dutch against Spain. The newly built Hanseatic Kontor in Antwerp was also looted several times. Cologne merchants tried to get compensation for the damage, but the Kontor lost its economic importance.

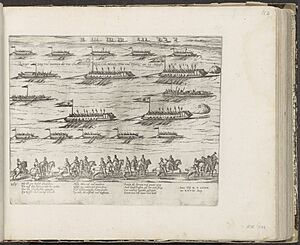

The Union of Arras and the Union of Utrecht in 1579 marked the beginning of the separation of the Spanish Netherlands, which eventually led to the independent states of the Netherlands and Belgium. Emperor Rudolf II tried to negotiate a peace settlement. A "Pacification Day" was held in Cologne from April to November 1579 because the city was a neutral and strategically important location with the necessary facilities for delegations. The negotiations took place in the Gürzenich, but they ended without any agreement.

Today, Cologne's Pacification Day is seen as the starting point for the creation of an independent Dutch state. The Dutch conflicts greatly affected Cologne's interests. In 1580, Dutch warships even came up the Rhine as far as Cologne, but a fleet of Rhenish electors quickly drove them off. The unrest disrupted Cologne's trade routes to Flanders and the Dutch controlled sea access to the Rhine, almost stopping Cologne's trade with England.

Early Modern Period

In the early modern period, the Reformation continued to influence Cologne's leaders. In 1582, Archbishop Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg converted to the Reformed faith and tried to change church practices in the city. The powerful Wittelsbach family strongly opposed this, leading to the Cologne War. Most of Cologne's population, following the cathedral clergy, preferred the Pope's influence over the Archbishop's. So, the city was spared the worst destruction that hit surrounding towns.

From 1583 to 1761, all ruling archbishops came from the Wittelsbach family. These powerful electors often challenged Cologne's free status in the 1600s and 1700s. These legal disputes were usually resolved in the city's favor through diplomacy.

During the period of witch persecutions (1435–1655), 37 people were executed in Cologne, mostly between 1626 and 1631 under Archbishop Ferdinand of Bavaria. One of the executed was Katharina Henot, Germany's first known female postmaster and an influential citizen. She was likely a victim of a conspiracy by her enemies among city officials.

Modern History

French and Prussian Rule

The French Revolutionary Wars led to the occupation of Cologne and the Rhineland in 1794. The French strengthened their control, and in 1798, Cologne became part of the new Département de la Roer. In the same year, the University of Cologne was closed. By 1801, all citizens of Cologne were granted French citizenship. In 1804, Napoléon Bonaparte visited the city with his wife Joséphine de Beauharnais. The French occupation ended in 1814 when Prussian and Russian troops took over Cologne. In 1815, Cologne and the Rhineland became part of Prussia.

Weimar Republic

After World War I, Cologne was occupied by the British Army of the Rhine until 1926, as part of the armistice and the Peace Treaty of Versailles.

Unlike the French, the British were more careful with the local people. Konrad Adenauer, who was mayor of Cologne from 1917 to 1933 and later became a West German chancellor, recognized that the British opposed French plans for a permanent occupation of the Rhineland.

The demilitarization of the Rhineland meant that the city's fortifications had to be taken down. This was a chance to create two "green belts" (Grüngürtel) around the city by turning the old fortifications and the clear areas around them into large public parks. This project was finished in 1933.

In 1919, Cologne University, which the French had closed in 1798, was reopened. It was seen as a replacement for the German University of Strasbourg, which became part of France. Cologne thrived during the Weimar Republic, making progress in city planning and social welfare. Its social housing projects were considered excellent and copied by other German cities.

Cologne even competed to host the Olympics, leading to the construction of a modern sports stadium at Müngersdorf. In the early 1920s, civil aviation was allowed again, and Cologne Butzweilerhof Airport quickly became a major hub for national and international air travel in Germany.

Nazi Germany

At the start of Nazi Germany, Cologne was seen as a difficult city by the Nazis because of strong communist and Catholic influences. The Nazis struggled to gain full control of the city.

In local elections on March 13, 1933, the Nazi Party won 39.6% of the vote. The Catholic Zentrum Party got 28.3%, the Social Democratic Party of Germany 13.2%, and the Communist Party of Germany 11.1%. The very next day, Nazi supporters took over the city hall. Communist and Social Democratic city assembly members were imprisoned, and Mayor Adenauer was dismissed.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, about 20,000 Jewish people lived in Cologne. By 1939, 40% had left the city. Most of those who remained were sent to concentration camps by 1941. The trade fair grounds near Deutz train station were used to gather Jewish people for deportation to death camps. On Kristallnacht in 1938, Cologne's synagogues were attacked or burned.

The Nazis planned to rebuild much of the inner city, including a main road connecting the Deutz station and the main station (which was to be moved). A huge field for rallies, the Maifeld, was planned. Only the Maifeld, between the campus and the Aachener Weiher lake, was built before the war. After the war, the Maifeld was covered with rubble from bombed buildings and turned into a park. In 2004, it was named Hiroshima-Nagasaki-Park to remember the victims of the nuclear bombs. A small memorial to the victims of the Nazi regime is on one of the hills.

On the night of May 30–31, 1942, Cologne was the target of the first 1,000 bomber raid of the war. Between 469 and 486 people, mostly civilians, were killed, over 5,000 were injured, and more than 45,000 lost their homes. Up to 150,000 of Cologne's 700,000 residents left the city after this raid. By the end of World War II, 90% of Cologne's buildings had been destroyed by Allied aerial bombing raids.

The bombings continued, and people kept moving out. By May 1945, only 20,000 residents remained out of 770,000.

US troops reached the outskirts of Cologne on March 4, 1945. The inner city on the left bank of the Rhine was captured quickly on March 6, 1945. Because the Hohenzollernbrücke bridge was destroyed by retreating German soldiers, the areas on the right bank remained under German control until mid-April 1945.

Postwar Cologne

Even though Cologne was larger than its neighbors, Düsseldorf was chosen as the political capital of the new Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia, and Bonn became the temporary capital of West Germany. Cologne benefited from being between these two important political centers by becoming home to many federal agencies and organizations. After Germany reunited in 1990, Cologne adjusted its role with the new federal capital, Berlin.

In 1945, architect Rudolf Schwarz called Cologne the "world's greatest heap of debris." Schwarz designed the 1947 reconstruction plan, which included building several new main roads through the city center, like the Nord-Süd-Fahrt (North-South-Drive). This plan considered the expected increase in car traffic after the war. The destruction of the famous twelve Romanesque churches, including St. Gereon's Basilica, Great St. Martin, and St. Maria im Kapitol, was a huge cultural loss. Rebuilding these churches and other landmarks like the Gürzenich was debated, but in most cases, the public desire to rebuild prevailed. The reconstruction lasted until the 1990s, when the Romanesque church of St. Kunibert was finished.

It took time to rebuild the city. In 1959, Cologne's population reached its pre-war numbers again. The city grew steadily, and in 1975, its population briefly exceeded one million. It stayed just under a million for the next 35 years before surpassing the million mark again in 2010.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Cologne's economy grew thanks to two main factors. First, the steady increase in media companies, both private and public. The new Media Park was developed to serve these companies, creating a striking visual center in downtown Cologne, including the KölnTurm (Cologne Tower), one of the city's tallest buildings. Second, improvements in traffic infrastructure made Cologne one of the most easily accessible metropolitan areas in Central Europe.

Due to the success of the Cologne Trade Fair, the city greatly expanded the fair site in 2005. The original buildings, from the 1920s, are now rented to RTL, Germany's largest private broadcaster, for their new headquarters.

The Cologne City Archive, which was the largest in Germany, is very important for Cologne's history. Its building collapsed on March 3, 2009, during the construction of an underground railway extension.

See also

- Timeline of Cologne

- Coat of arms of Cologne

- History of the Jews in Cologne

- Cologne colonial history

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |