History of Norfolk facts for kids

Norfolk is a county in the East of England known for its countryside. People have lived in Norfolk since the last Ice Age. Tools, coins, and hidden treasures found here show that many busy communities once lived in this area.

Before the Roman conquest of Britain in 43 AD, the Iceni tribe lived in Norfolk. After the Romans arrived, they built roads, forts, large houses called villas, and towns. The famous Iceni queen, Boudica, led a rebellion in 60 AD against the Romans. After her revolt, there was a time of peace until the Roman armies left Britain in 410 AD. When the Anglo-Saxons arrived, much of the Roman and British culture in Norfolk was lost. By about 800 AD, Anglo-Saxons had settled all of Norfolk, and the first towns began to appear. Norfolk was the northern part of the Kingdom of East Anglia, ruled by the Anglo-Saxon Wuffing family.

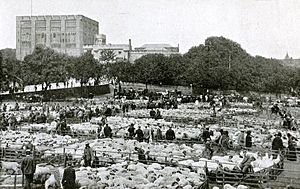

During the time of the Normans, Norwich became the most important city in the region. It grew steadily and had strong connections with other countries, making it a major mediaeval city. However, it faced problems like arguments among people, unhealthy conditions, and terrible fires. Mediaeval Norfolk was the most crowded and productive farming area in England. Farmers grew many crops, and the wool trade was big, supported by huge flocks of sheep. Other industries, like digging for peat, were also important. Norfolk was a rich county with many monasteries and parish churches.

Contents

What Does "Norfolk" Mean?

The name "Norfolk" comes from old words meaning "the northern people." It was first written down in Anglo-Saxon wills between 1043 and 1045. Later, it appeared as Norðfolc in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and as Nordfolc in the Domesday Book. Some people also think the name might come from the words 'Norse' and 'Folk'.

Norfolk's Ancient History

Early Stone Age to Copper Age

Lower Paleolithic (Old Stone Age)

(2,500,000 to 300,000 BC) In 2005, scientists found some of the oldest signs of human life in Europe right here in Norfolk. They discovered flint tools, which are like very old stone knives. Some tools found at Happisburgh are about 900,000 years old! They also found ancient footprints and the oldest hand axe in north-west Europe.

Middle Paleolithic (Middle Stone Age)

(300,000 to 30,000 BC) A big discovery was made in 2002 in Thetford Forest at Lynford. It was one of the most important sites for Neanderthal people, dating back to around 58,000 BC. Archaeologists found a well-preserved hand axe and 30 more like it. They also found reindeer bones with cut marks, showing that Neanderthals might have hunted and butchered animals here. Animals like woolly mammoths, woolly rhinoceros, and spotted hyenas lived in Norfolk back then. Even with these exotic animals, it was still very cold, like an Ice Age, with average summer temperatures around 13 °C.

Upper Paleolithic (Late Stone Age)

(40,000 to 10,000 BC) During the last Ice Age, about 22,000 to 17,000 years ago, all of Britain was covered in ice or was a polar desert. This meant no humans lived here. But about 15,000 years ago, new groups of people started to return to Britain.

Neolithic (New Stone Age) and Chalcolithic (Copper Age)

(9500 to 3000 BC) This time period shows how people changed from using stone tools to starting to use metals. The Copper Age was when people first learned to work with simple metals like copper, silver, tin, and gold. This came before the Bronze Age, when people learned to mix metals to make stronger materials like bronze.

Bronze Age (3000 to 600 BC)

Norfolk was a major place for working with metals during the Late Bronze Age. In 1998, a special discovery was made near Holme-next-the-Sea. A ring of wooden timbers was found, with an upside-down tree stump in the middle. This site, called Seahenge, was built around 2049 BC.

Many other Bronze Age items have been found, including 141 axe heads at Foulsham and pottery from the Witton Wood barrow.

Grimes Graves is a large and well-preserved group of Neolithic flint mines near Brandon. There are 400 pits where people dug for flint over 5,000 years ago. The Anglo-Saxons later named the site Grim's Graves.

Iron Age

Evidence shows that people farmed much of Norfolk very intensely during the Late Iron Age. The Cenimagni tribe, who gave up to Caesar in 54 BC, lived in Norfolk at this time. They might have been based in north-west Norfolk, where treasures like the Snettisham coins and torcs (necklaces) were found. Coins found in the south of the county suggest the Iceni tribe might have been centered around Thetford by the mid-1st century AD.

Roman Norfolk

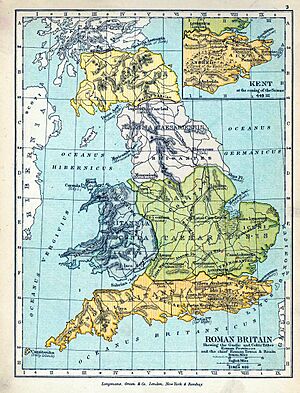

Norfolk's coastline looked very different when the Romans first arrived. The northern coast has worn away over the last two thousand years. The eastern coast had a huge estuary (where a river meets the sea). The Wash was much bigger, and the area now called the Fens was a huge, difficult-to-cross marsh with islands.

After the Romans took over Britain in 43 AD, they built forts and roads in Norfolk. Important Roman roads included the Peddars Way and Pye Road. After a small rebellion by the Iceni in 47 AD, King Prasutagus was allowed to rule his people as a client king (meaning he ruled under Roman control). When he died in 60 AD, the Romans took full control. His wife, Boudica, was not allowed to become queen because Roman law only allowed men to inherit a client king's title. After Boudica was insulted, she led a rebellion where she attacked and destroyed the towns of Colchester, London, and St. Albans.

After Boudica's defeat, the Romans brought order back to the region. They set up a main center at Venta Icenorum (now Caistor St. Edmund), a small town at Brampton, and other settlements near river crossings or road junctions. Most people lived in small farms, villages, or richer Roman villas. The sea level dropped during Roman times, and the swamps in western Norfolk slowly dried out. This land became fertile farmland, good for raising sheep and salt production.

The Saxon Shore forts were built by the Romans in the 3rd century AD to defend against raiders from the sea. In Norfolk, you can still see the ruins of the fort at Burgh Castle (Roman Gariannonum). This fort guarded the estuary. There is little left of the forts at Brancaster and Caister-on-Sea. After the last Roman armies left in 410 AD, most of the Roman buildings slowly disappeared.

Anglo-Saxon Norfolk

New People and Settlements

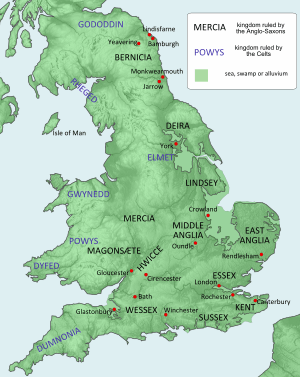

During the 4th century, fewer people lived in the area, possibly because of raids from Saxons and Picts. Around 410 AD, people who spoke Germanic languages started arriving from north-west Europe. This means the first Anglo-Saxon settlements in Norfolk happened even before the famous landing of Hengist and Horsa in Kent in 449. Many new settlers came, but they didn't arrive as one big group. The idea of people in this region being called Angles probably came later.

The new Anglo-Saxon culture replaced the Roman and ancient British ways of life. There are very few British place names left in this area. Most of the place names in Norfolk were created much earlier, even though they were first written down in the 11th-century Domesday Book. Places in Norfolk with names ending in -ham (like Dereham) are usually found near rivers or good soil. These places grew from large villages into the market towns we know today. Smaller settlements often ended with -ton, -wick, or -stead.

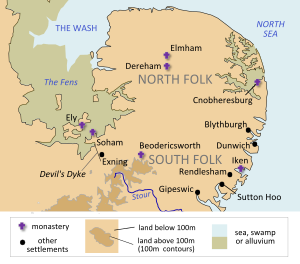

Digs and place names show that early Anglo-Saxons (before 800 AD) settled most densely in the south and south-west of Norfolk, especially along rivers. A settlement and a cemetery at Spong Hill is one of the earliest Anglo-Saxon sites found in Norfolk. In the 7th century, East Anglia became Christian, and the custom of burying grave goods (items with the dead) stopped. We know about early Anglo-Saxon settlement from pottery and coins found from that time.

The Anglo-Saxons eventually spread across all of Norfolk. By 850 AD, most of the county's current place names (before the Danes arrived) had been created. Evidence of important trading towns like Thetford and Norwich is still being found. Many other sites in the county show Anglo-Saxon settlement, such as North Elmham (with timber buildings and roads) and Bawsey (with pottery, coins, and metalwork). Six beautiful late Anglo-Saxon silver brooches were found at Pentney in 1978.

Some historians think that more Britons continued to live in the Fenlands. In that area, you can find some place names that might have Celtic (British) origins, like King's Lynn.

The Kingdom of the East Angles

Norfolk was part of the kingdom of the East Angles for much of the Anglo-Saxon period. We don't know much about its history from this time, as many old records are lost. The history of Norfolk, the northern part of the kingdom, is hard to tell apart from the rest of East Anglia during this period.

East Anglia was first ruled by kings from the Wuffings family. The most important historical source, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, mentions kings like Rædwald of East Anglia and Edmund the Martyr. Another important source is Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, which describes events during the reigns of several East Anglian kings.

The Vikings attacked Norfolk in 865. Four years later, they killed Edmund, the last king of the East Angles. Villages on the former island of Flegg, like Scratby, Hemsby, and Filby, show signs of Viking settlement. Other Viking place names are found around Norfolk. Viking settlement is thought to have helped towns like Norwich and Thetford grow. After Edward the Elder conquered East Anglia and ended Viking rule around 917, the region became part of the kingdom of England.

Mediaeval Norfolk

When the Norman Conquest happened in 1066, Norfolk was part of the land owned by Harold I of England. Norfolk did not fight against William the Conqueror. William gave the land to Ralph de Gael. After Ralph rebelled in 1075, his lands were taken away and given to Roger Bigod.

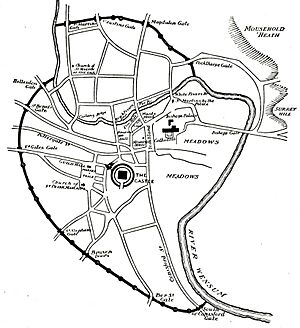

Mediaeval Norwich

When the Normans arrived in 1066, much of Anglo-Saxon Norwich was destroyed. After Ralph de Gael rebelled, the Normans burned a large part of the town. Then, they began to make Norwich a busy international port and a center of Norman power. Norwich Castle was built by 1075. It was first a wooden motte and bailey castle, then rebuilt in stone before 1200. Work on Norwich Cathedral began in 1096. A large part of the town became a building site for the cathedral, a fortified bishop's palace, and other monastic buildings.

Early mediaeval Norwich grew into a city with people from many places. It expanded around the waterfront and westwards. In the 12th century, there was a thriving Jewish community, but they were not popular with the Christian population.

Between 1297 and 1344, a new defensive wall was built around the city. This wall replaced older wooden fences and gates. The area inside the walls was the largest for any city in England. Even so, there was still a lot of open land inside, which was slowly filled with new monasteries, houses, markets, and workshops. By 1400, Norwich had grown into a major city with perhaps 10,000 people.

The Black Death (a terrible plague) may have killed two-fifths of the city's population. This led to efforts to make the city cleaner, but they didn't help much. People soon moved in from the countryside, and the population returned to its previous numbers, partly because of the growing textile industry. The city's increasing wealth and pride were shown in new large buildings like the Guildhall, built from 1407 to 1453. Later in the mediaeval period, Norwich's fortunes declined. Fires in 1412 and 1413 destroyed many buildings, and the Wars of the Roses also contributed to its decline. This period saw a growing gap between the rich and the poor in Norwich.

Life in Rural Norfolk During the Middle Ages

In the 14th century, Norfolk was the most crowded and most intensely farmed region in England. Most of the land was used for growing crops, much more than in earlier centuries. Where land was hard to plough, it was used as pasture for animals. Many of Norfolk's woodlands were cleared during mediaeval times. The soils in the county varied, from light to heavy, with the most valuable being moderately heavy soils in central and eastern parts. Farmers grew crops like barley (for making beer), rye, oats, and peas. Horses were used for farming earlier in Norfolk than elsewhere, and crop rotation helped farmers grow more.

Like the rest of the country, the Church was very important in mediaeval Norfolk. More mediaeval parish churches were built here than in any other English county. Norwich alone once had sixty-two churches! Over time, the number has slowly gone down. Many new monastic communities were started during the Middle Ages. You can still see large remains of several religious houses around Norfolk, such as at North Creake, Binham, Little Walsingham, Castle Acre, and Thetford Priory.

Over twenty castles were built in Norfolk during the Middle Ages. The most impressive is Norwich Castle, built soon after the Norman Conquest. Many castles, like those at Great Yarmouth and Lynn, no longer exist. Most early castles were small and made of timber. The remains of stone castles in Norfolk include those at Castle Rising, Castle Acre, and Buckenham. Many examples of earthwork remains (mounds and ditches) still exist.

The Norfolk Broads were created because people dug out huge amounts of peat and clay during the Middle Ages. These were once deep pits, up to 15 feet deep. Digging for peat might have started in the Anglo-Saxon period, but the first records are from mediaeval abbey documents. Flooding caused by the sea breaking through the coast made the peat pits fill with water. Over time, these pits became permanently flooded, and people forgot how the new 'broads' were formed.

In the wars between King John and his barons, Roger Bigod defended Norwich Castle against the king.

The story of Julian of Norwich (1342 – c. 1429) also comes from this time. She is famous for being the first woman to write a book in English.

The Battle of North Walsham happened on June 25 or 26, 1381. It marked the end of fighting in Norfolk during the Peasants' Revolt. The rebels, led by Geoffrey Litster, were defeated by a force led by Henry le Despenser, the Bishop of Norwich. This site is one of only five known battlefields in Norfolk.

Another legend from Norfolk from this period is the Pedlar of Swaffham. You can still see parts of this story in the church choir area. There are two wooden pews: one has carvings of a pedlar and his dog, and the other shows a woman looking over a shop door.

Norfolk During the Tudor and Stuart Times

Kett's Rebellion (1549)

After local landowners' enclosed lands were destroyed, thousands of people joined Robert Kett in a march on Norwich. They set up a large, organized camp at Mousehold Heath in July 1549. The rebellion was mainly because of land enclosure, the theft of shared resources, and the unfair use of power by the rich. The authorities tried to stop them by offering a pardon, but it failed. Norwich's city gates were closed to the rebels, but they still managed to break through and take over the city.

In London, the government sent the Marquess of Northampton to take back Norwich. He entered the city without a fight at first, but the rebels forced him and his army to retreat to Cambridge.

From this point, Kett was less successful. He failed to spread the rebellion to Great Yarmouth. The Earl of Warwick reached Norwich and entered the city with a large force. Even though they were outnumbered, Kett's men refused a pardon. After intense street fighting, they were forced to return to Mousehold Heath. Kett tried to recapture the city, but more mercenaries arrived to support Warwick, forcing Kett to abandon his camp. In a fierce battle outside the city on August 27, 1549, the rebels were defeated, and Kett was captured. He was later found guilty of treason and hanged.

Norfolk During the English Civil War

Norfolk supported Parliament during the English Civil War, though some people still supported the King. The defenses of Norwich and the main ports were made stronger. In December 1642, the Eastern Association was formed to prepare the region for war. However, little fighting happened in Norfolk, as Parliament controlled it throughout the war. In September 1643, a mob against Catholics caused a lot of damage to Norwich Cathedral, which was then taken over by soldiers the next year.

The only serious fighting in Norfolk during the Civil War was at King's Lynn, where support for the King was strongest. In April 1643, Parliament investigated King's Lynn and ordered the arrest of the town's main Royalists. That August, believing the King's forces would arrive soon, the town openly declared its support for the King. The town was attacked by the Earl of Manchester and damaged by bombs. However, Parliament had trouble gathering enough forces, and the town only surrendered after Manchester threatened to storm the defenses on September 16. Any hopes Royalists had of helping the King in Norfolk ended.

In 1646, a series of events led to a notable disaster in Norfolk. Tensions were rising in the county due to higher taxes and rising grain prices. Also, the central government was getting more involved in local affairs. This led to many acts of resistance across the county in 1646, including riots in Norfolk and King's Lynn. Norwich, the county's largest city, was divided between people who liked traditional culture and those who were Puritans. In 1647, the citizens elected John Utting, which angered local Puritans. Utting supported traditional entertainment like taverns and plays, and he didn't want to ban holidays like Christmas, which many apprentices supported but infuriated the Puritans.

When a Parliament representative tried to arrest Utting, the situation became explosive. On April 24, 1648, angry townspeople in Norwich rioted and attacked the homes of important Puritans. News of troops arriving to restore order made people even angrier. In their search for weapons, they stormed the County Committee headquarters. During this confusing time, rioters who had taken weapons from the armory accidentally set off barrels of gunpowder. This caused a huge explosion, known as "The Great Blow," which destroyed much of the city and caused many deaths. This explosion brought the rioting in the city to a sudden stop.

Norfolk in the 18th Century

In 1785 and 1786, the first hot air balloon flights happened in Norfolk. Several manned gas balloon flights took off from Quantrell's Gardens in Norwich.

Norfolk in the 19th Century

In the mid-19th century, over a hundred Norfolk families owned large estates bigger than 2,000 acres. There were also many smaller landowners. After 1875, a long period of economic difficulty in English farming and industry began. This reduced the income from estates and put great pressure on their owners. Debts and high spending, often over many generations, made things worse. The introduction of Death Duties in 1894 also added to their problems.

Landowners who were in debt had to sell their property, rent out their estates for shooting, reduce staff, or move elsewhere. Estates were neglected as owners tried to save money. Many estates disappeared as farms, parks, and woodlands were sold off, and large houses were left to decay. After 1880, many larger estates changed hands, were broken up, or became smaller as farmers and business people from outside the county bought land. A housing boom in the 1890s, caused by a big increase in Norfolk's population, allowed some landowners near towns and coastal resorts to make money from selling their land.

Norfolk in the 20th Century

The First World War was very important for Norfolk. Many men of fighting age were called to join local regiments and fight in France. Almost every village in Norfolk has a war memorial listing the names of those who died.

The war was the first time that a lot of aviation (flying) activity happened across the county. Many airfields and landing grounds were built. Notably, Pulham Market in the south of the county was one of the few places where airships were based. Companies like Boulton and Paul in Norwich and Savages of Kings Lynn were involved in building hundreds of aircraft for the war effort. Boulton and Paul still exist today as a joinery company and were involved in aviation until the 1960s.

Another company, Lawrence Scott & Electromotors, also helped with the war effort by making shells and electrical motors for the Navy.

Norfolk was one of the first places on Earth to be bombed from the air when German Zeppelin airships raided the county several times. Late in the war, Zeppelin L70 was shot down off the Norfolk Coast by Major Egbert Cadbury of the Royal Air Force. The commander of the German Naval Airship Service, Peter Strasser, was on board the Zeppelin, and everyone on board died. Some of the men were buried in churchyards along the coast.

See also

- Catch-land

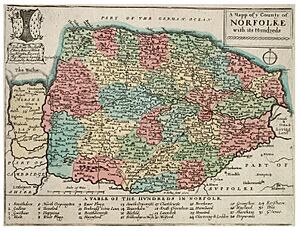

- Hundreds of Norfolk

- Iceni

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |