History of U.S. foreign policy, 1776–1801 facts for kids

The history of how the United States dealt with other countries from 1776 to 1801 is a story of a new nation finding its way in the world. For the first part of this time, the U.S. foreign policy was guided by the Second Continental Congress and the Congress of the Confederation. After the U.S. Constitution was approved in 1788, foreign policy was handled by Presidents George Washington and John Adams. When Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801, a new chapter in U.S. foreign policy began.

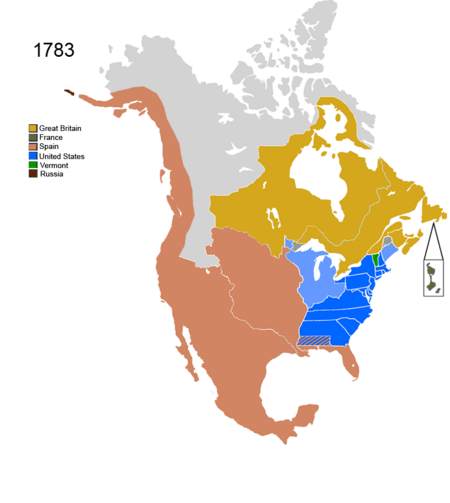

After the American Revolution started in 1775, the United States looked for help from European countries in its fight against Great Britain. Benjamin Franklin helped create an alliance with France in 1778. France played a huge part in America winning the war. Spain and the Dutch Republic also helped the U.S. Other European countries joined the First League of Armed Neutrality to protect their ships from the Royal Navy. The war ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. This treaty gave the United States control of land all the way to the Mississippi River.

In the years after the war, relations with Great Britain and Spain were very important. Both countries made it hard for Americans to settle in the west. They controlled key areas and made friends with Native American tribes. The U.S. also started trading more with different countries. Because the U.S. government was not very strong at first, it couldn't make a trade deal with Great Britain or fight back against high British taxes on goods.

When the U.S. Constitution was approved, George Washington became president in 1789. That same year, the French Revolution began. This led to many years of war between France, Britain, and other European powers, which lasted until 1815. The French Revolution caused a big split in the United States. Some, like Thomas Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans, supported France. Others, like Alexander Hamilton and the Federalists, disliked the revolution and favored Britain.

As a neutral country, the United States wanted to trade with both France and Britain. But ships from both countries attacked American ships that were trading with their enemies. President Washington wanted to stay out of foreign conflicts. He issued the Proclamation of Neutrality in 1793. In 1795, Washington's government made the Jay Treaty with Britain. Under this treaty, Britain agreed to open some ports to U.S. trade and leave their forts in U.S. territory in the west. That same year, the Washington administration made the Treaty of San Lorenzo with Spain. This treaty settled border disputes and allowed American ships to use the Mississippi River freely.

In 1798, an undeclared naval war with France, called the Quasi-War, started after France attacked more American ships. The war ended with the Convention of 1800. However, attacks on American ships by France and Britain would start again in the 1800s.

Contents

Leading the Nation's Foreign Policy

Second Continental Congress (1775–1781)

The Second Continental Congress was the main government of the United States. It led the country from the start of the American Revolutionary War in 1775 until the Articles of Confederation were approved in 1781.

Congress of the Confederation (1781–1789)

In 1776, Congress created a plan for the new nation's government. This plan became the Articles of Confederation. It set up a weak national government that had little power over the states. Under the Articles, states could not make deals with other countries or have their own armies without Congress's permission. But most other powers belonged to the states. Congress could not collect taxes or tariffs. It also couldn't make states follow its laws. Because of this, Congress relied heavily on the states to cooperate.

In 1781, Congress created departments for foreign affairs, the military, and money. Robert Morris, who was in charge of money, made big changes. He helped create the Bank of North America. Morris became a very powerful person in the government. Robert Livingston was the Secretary of Foreign Affairs from 1781 to 1783. He was followed by John Jay, who led the nation's diplomacy from 1784 to 1789. In 1776, the Continental Congress had written the Model Treaty. This treaty guided U.S. foreign policy in the 1780s. It aimed to remove trade barriers like tariffs and avoid getting involved in political or military conflicts.

Washington Administration (1789–1797)

George Washington became president in 1789. The new Constitution allowed the president to choose leaders for government departments with the Senate's approval. These leaders, called the cabinet, included the Secretary of War, Secretary of State, Secretary of Treasury, and Attorney General. Washington held regular cabinet meetings.

Washington first offered the Secretary of State job to John Jay. But Jay preferred a court position. So, Washington chose Thomas Jefferson as the first Secretary of State. For the important job of Secretary of the Treasury, which handled money matters, Washington picked Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton and Jefferson had very different ideas. Their disagreements often shaped cabinet discussions.

Washington saw himself as an expert in foreign affairs and military matters. He was often his own Foreign Secretary and War Secretary. Jefferson left the cabinet in 1793. He was replaced by Edmund Randolph. Randolph, like Jefferson, often favored France in foreign policy. But he didn't have much power in the cabinet. Other cabinet members also left during Washington's second term. Timothy Pickering became Secretary of State in 1795.

Adams Administration (1797–1801)

John Adams became president in 1797. Instead of choosing his own team, Adams kept Washington's cabinet members. However, many of these cabinet members, like Timothy Pickering, James McHenry, and Oliver Wolcott Jr., were loyal to Hamilton. They often asked Hamilton for advice and worked against Adams's ideas.

As Adams and Hamilton's supporters grew apart, Adams relied less on these cabinet members. When Adams realized Hamilton was secretly influencing his cabinet, he fired Pickering and McHenry in 1800. He replaced them with John Marshall and Samuel Dexter.

American Revolution Diplomacy

The American Revolutionary War against British rule began in April 1775. The Second Continental Congress met in May 1775. They created an army led by George Washington. On July 4, 1776, Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence. Britain struggled with diplomacy during the war. Most of Europe stayed neutral, but many people and leaders favored the American Patriots.

France

In 1776, Silas Deane was sent to France by Congress. His goal was to get financial help from the French government. In Paris, Deane talked with French officials and got many weapons and supplies shipped to America. He also helped recruit European soldiers like Lafayette and Baron von Steuben.

Arthur Lee was sent to Spain and Prussia to get their support. King Frederick the Great of Prussia disliked the British. He quietly made it harder for Britain to fight, like blocking German soldiers from passing through his land. But he stayed officially neutral because trade with Britain was too important. Spain wanted to fight Britain but was worried about the idea of a republic like the U.S. It feared this idea could threaten its own colonies in Latin America.

In December 1776, Benjamin Franklin went to France. Franklin used his charm to get more French support, beyond secret loans and volunteers. After the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga, France officially became an ally against Britain. The alliance was signed on February 6, 1778. It was a defensive agreement where both sides promised to help each other if Britain attacked. Neither country would make a separate peace with London until the Thirteen Colonies' independence was recognized. French help was key to America winning the Revolutionary War.

Spain

Spain was not an official ally of the United States. But they had an informal alliance with Bernardo de Gálvez, the Spanish governor of Louisiana. In 1779, Spain signed the Treaty of Aranjuez with France. France agreed to help Spain capture Gibraltar, Florida, and Menorca. On June 21, 1779, Spain declared war on England.

Spain's economy depended on its colonies in the Americas. They worried about the United States expanding its territory. Because of these concerns, Spain kept rejecting John Jay's attempts to set up diplomatic relations. Spain was one of the last countries to recognize the United States' independence, on February 3, 1783. Britain recognized U.S. independence in the Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783. The U.S. set up diplomatic relations with London in 1785. John Adams was the first American representative to Great Britain.

The Dutch Republic

In 1776, the United Provinces was the first country to salute the Flag of the United States. This made Britain suspicious of the Dutch. In 1778, the Dutch refused to join Britain in the war against France. The Dutch were major suppliers to the Americans. For example, from 1778 to 1779, over 3,000 ships sailed from the island of Sint Eustatius in the West Indies. When the British started searching all Dutch ships for weapons for the rebels, the Dutch officially adopted a policy of armed neutrality. Britain declared war in December 1780. This led to the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, which used up British resources but also showed the decline of the Dutch Republic.

In 1782, John Adams arranged loans of $2 million from Dutch bankers for war supplies. On March 28, 1782, after Adams and Dutch politician Joan van der Capellen campaigned for the American cause, the United Netherlands recognized American independence. They then signed a treaty of commerce and friendship.

Neutrals

The First League of Armed Neutrality was an alliance of smaller European naval powers from 1780 to 1783. Its goal was to protect neutral shipping from the British Royal Navy. The British often searched neutral ships for French goods during the war. Empress Catherine II of Russia started the League in March 1780. She said neutral countries had the right to trade by sea with warring countries without problems, except for weapons. Russia would only recognize blockades of individual ports, not whole coasts, and only if a warship was actually there.

The Russian navy sent ships to the Mediterranean, Atlantic, and North Sea to enforce this rule. Denmark and Sweden joined Russia, adopting the same policy. The three countries signed the agreement forming the League. They stayed out of the war but threatened to fight back if their ships were searched. By the time the Treaty of Paris ended the war in 1783, many other countries had joined the League. Even though the British Navy was much larger, the alliance had diplomatic power. France and the United States quickly supported the idea of free neutral trade.

Treaty of Paris (1783)

After the American victory at the Battle of Yorktown in September 1781, and the British Prime Minister Lord North's government fell in March 1782, both sides wanted peace. The American Revolutionary War ended with the signing of the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

The treaty gave the United States independence. It also gave the U.S. control of a huge area south of the Great Lakes. This land stretched from the Appalachian Mountains west to the Mississippi River. Some Americans had hoped to get Florida, but that land went back to Spain. The British successfully kept Canada.

Many historians say Britain's land concessions were very generous. They believe Britain wanted to have strong economic ties with the U.S. The treaty aimed to help the American population grow and create good markets for British merchants. This would happen without military or administrative costs for Britain. As the French foreign minister Vergennes said, "The English buy peace rather than make it."

The treaty also dealt with other issues. The United States agreed to pay back debts from before 1775. The British agreed to remove their soldiers from American land. Americans lost special trading rights they had as part of the British Empire. This included protection from pirates in the Mediterranean Sea. Neither side fully honored these extra parts of the treaty. Some states ignored their duties by not returning property taken from Loyalists. The British often ignored the part about removing slaves.

Western Settlement in the 1780s

Before the Revolutionary War, only a few Americans lived west of the Appalachian Mountains. The war removed barriers to settlement. By 1782, about 25,000 Americans had moved to this western area. After the war, more Americans continued to settle there. Life was hard, but western settlement offered the chance to own land, which was difficult for some in the East.

Southern leaders and many nationalists supported the settlers. But most Northern leaders cared more about trade than western settlement. The weak national government couldn't force other countries to make concessions. In 1784, Spain closed the Mississippi River. This stopped western farmers from shipping their goods to the sea, making it very hard to settle the West. Spain also gave weapons to Native Americans.

In western territories, mainly in present-day Wisconsin and Michigan, the British kept control of several forts. They also continued to make friends with Native Americans. These actions slowed U.S. settlement. They also allowed Britain to profit from the valuable fur trade. The British said they stayed in the forts because Americans had blocked the collection of pre-war debts owed to British citizens.

Between 1783 and 1787, hundreds of settlers died in small conflicts with Native Americans. These conflicts discouraged more settlement. Congress gave little military support against the Native Americans. Most of the fighting was done by the settlers themselves. By the end of the 1780s, the frontier was involved in the Northwest Indian War. This was against a group of Native American tribes called the Northwestern Confederacy. These Native Americans wanted to create an independent Indian barrier state with British support. This was a big foreign policy challenge for the United States.

Economy and Trade in the 1780s

A short economic downturn followed the war, but good times returned by 1786. Trade with Britain started again. The amount of British goods imported after the war was the same as before the war. But American exports dropped sharply. John Adams, who was the ambassador to Britain, asked for a retaliatory tax on British goods. He hoped this would force Britain to make a trade treaty, especially about access to Caribbean markets.

However, Congress didn't have the power to control foreign trade. It also couldn't make the states follow a single trade policy. So, Britain was unwilling to negotiate. While trade with the British didn't fully recover, the U.S. traded more with France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and other European countries. Despite these good economic conditions, many traders complained about the high taxes each state put on goods. This limited trade between states. Many lenders also suffered because state governments failed to pay back debts from the war. Even though the 1780s saw some economic growth, many people felt worried about money. Congress often got the blame for not creating a stronger economy.

French Revolution (1789-1796)

Public Debate

When the Storming of the Bastille happened on July 14, 1789, the French Revolution began. Most Americans were excited. They remembered France's help during the Revolutionary War. They hoped for democratic changes that would strengthen the Franco-American alliance. They also hoped France would become a republic like the U.S.

Soon after the Bastille fell, the main prison key was given to Marquis de Lafayette. Lafayette was a Frenchman who had fought with Washington in the American Revolution. He sent the key to Washington as a sign of hope for the revolution. Washington proudly displayed it in his home.

In the Caribbean, the revolution caused problems in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). The government split into royalist and revolutionary groups. People there started demanding civil rights. Seeing an opportunity, the slaves in northern Saint-Domingue planned a huge rebellion. It began on August 22, 1791. Their successful revolution led to the creation of the second independent country in the Americas (after the United States). Soon after the revolt, Washington's government sent money, weapons, and supplies to Saint-Domingue. This was at France's request, to help the colonists. Many Southerners feared that a successful slave revolt in Haiti would lead to a big race war in America. American aid to Saint-Domingue was part of the U.S. repayment of Revolutionary War loans. It totaled about $400,000 and 1,000 military weapons.

From 1790 to 1794, the French Revolution became more extreme. In 1792, the revolutionary government declared war on several European nations, including Great Britain. This started the War of the First Coalition. In late summer, bloody massacres spread through Paris and other cities. More than a thousand people died. On September 21, 1792, France declared itself a republic. King Louis XVI was executed on January 21, 1793. Then came a period called the "Reign of Terror" (1793-1794). During this time, over 16,000 people accused of being enemies of the revolution were executed. Some who had helped the American rebels, like navy commander Comte D'Estaing, were killed. Lafayette fled France and was imprisoned in Austria. Thomas Paine, who was in France to support the revolutionaries, was also imprisoned.

Most Americans initially supported the revolution. But the debate in the U.S. about the revolution's nature soon made existing political divisions worse. It led to political leaders taking sides: pro-French or pro-British. Thomas Jefferson led the pro-French group. They celebrated the revolution's republican ideals. Alexander Hamilton, though initially supportive, soon led the group that doubted the revolution. They believed "absolute liberty would lead to absolute tyranny." They wanted to keep trade ties with Great Britain.

When news reached America that France had declared war on Britain, people were divided on whether the U.S. should join France. Jefferson and his group wanted to help the French. Hamilton and his followers supported neutrality. Jefferson's supporters called Hamilton, Vice President Adams, and even the president "friends of Britain" and "enemies of republican values." Hamilton's supporters warned that Jefferson's Republicans would bring the terrors of the French revolution to America. They feared "crowd rule" and the destruction of "all order and rank in society and government."

Genet Affair and Neutrality (1793)

President Washington wanted to avoid foreign conflicts. But many Americans were ready to help the French fight for "liberty, equality, and fraternity." After Washington's second inauguration, France sent diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt, known as "Citizen Genêt," to America. Genêt's job was to gather support for France. He gave permission to 80 American merchant ships to capture British merchant ships. He held big, excited rallies where Americans cheered for France and booed President Washington. He argued against neutrality and created groups called Democratic-Republican Societies in major cities.

Washington was very annoyed by Genêt's interference. When Genêt allowed a French warship to sail from Philadelphia against direct presidential orders, Washington demanded that France recall Genêt. Jefferson agreed. By this time, the revolution in France had become more violent. Genêt would have been executed if he returned to France. Washington allowed him to stay, making him the first political refugee in the United States.

Washington, after talking with his cabinet, issued a Proclamation of Neutrality on April 22, 1793. In it, he declared the United States neutral in the war between Great Britain and France. He also threatened legal action against any American who helped any of the warring countries. Washington realized that supporting either Great Britain or France was a bad idea. He would do neither, protecting the young U.S. from harm. The Proclamation became law with the Neutrality Act of 1794.

The public had mixed feelings about Washington's Proclamation of Neutrality. Genêt had stirred up many Americans, making foreign policy a big issue. Jefferson's supporters generally opposed Britain and supported the French Revolution. They welcomed an old nation gaining freedom from tyranny. However, merchants worried that supporting France would ruin their trade with the British. This economic reason was why many Federalist supporters wanted to avoid more conflict with the British. Meanwhile, Hamilton used the public's reaction against Genêt to build support for his anti-French Federalist group. These events were known as the Genet Affair or the French Neutrality Crisis.

British Seizures

When Britain went to war against France, the Royal Navy started stopping ships from neutral countries heading to French ports. The French imported a lot of American food. The British hoped to starve the French into defeat by stopping these shipments. In November 1793, the British government expanded these seizures. They included any neutral ships trading with the French West Indies, even American ones. By March, over 250 U.S. merchant ships had been seized.

Americans were furious. Angry protests broke out in several cities. Many Jeffersonians in Congress demanded a declaration of war. But Congressman James Madison instead called for strong economic action, like stopping all trade with Britain. While this was being debated, news arrived that the Governor General of British North America, Lord Dorchester, had made a speech that encouraged Native tribes in the Northwest Territory against the Americans. This made anti-British feelings in Congress even stronger.

Congress responded by passing a 30-day ban on all shipping in American harbors. Meanwhile, the British government had partly canceled its November order. This change in policy didn't stop the whole movement for trade retaliation, but it calmed things down a bit. The ban was extended for a second month, but then allowed to expire. In response to Britain's more peaceful policies, Washington sent Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay as a special envoy to Great Britain to avoid war. This appointment angered Jeffersonians. Even though the Senate approved it (18–8), the debate was harsh.

Jay Treaty (1796)

Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to London in 1794 to negotiate a treaty with Britain. Hamilton told Jay to seek payment for seized American ships. He also wanted Jay to clarify the rules for British seizure of neutral ships. Jay was also to insist that the British leave their forts in the Northwest. In return, the U.S. would take responsibility for pre-Revolution debts owed to British merchants. Jay also asked, if possible, for limited access for American ships to the British West Indies.

Jay and the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Grenville, started talks on July 30, 1794. The treaty that came out weeks later, known as the Jay Treaty, was, in Jay's words, "equal and fair." Both sides achieved many goals. Several issues were sent to arbitration. For the British, America stayed neutral and grew closer economically to Britain. Americans also promised good treatment for British imports. In return, the British agreed to leave the western forts, which they were supposed to do by 1783. They also agreed to open their West Indies ports to smaller American ships. They allowed small vessels to trade with the French West Indies. They set up a commission to decide American claims against Britain for seized ships. They also set up a commission for British claims against Americans for debts from before 1775. Since the treaty didn't include agreements on impressment (forcing sailors into service) or rights for American sailors, another commission was later set up for those issues and boundary disputes.

When the treaty arrived in Philadelphia in March 1795, Washington had doubts about its terms. He kept its contents secret until June, when the Senate met to approve it. Washington faced a tough choice. If he supported the treaty, his government might fall apart due to political anger. If he put the treaty aside to silence critics, there would likely be war with Great Britain, which could also destroy the government. The debate on the treaty's 27 articles was secret and lasted over two weeks. Republican senators, who wanted to push Britain to the edge of war, called the Jay Treaty an insult to American honor. They said it rejected the 1778 treaty with France. On June 24, the Senate approved the treaty by a vote of 20–10. This was the exact two-thirds majority needed for approval.

The Senate hoped to keep the treaty secret until Washington signed it. But it was leaked to a Philadelphia editor who printed it in full on June 30. Within days, the whole country knew the terms. Many people were outraged, saying Jay had "betrayed his country." The reaction was most negative in the South. Southern planters, who owed pre-Revolution debts to the British and wouldn't get paid for lost slaves, felt insulted. As a result, Federalists lost most of their support among planters. Republicans organized protests, including petitions, angry pamphlets, and public meetings in big cities. Each meeting sent a message to the president.

As protests grew, Washington's neutral stance shifted to strong support for the treaty. Hamilton's detailed analysis and newspaper essays promoting it helped. The British, to encourage the treaty's signing, delivered a letter that showed Edmund Randolph had taken bribes from the French. Randolph was forced to resign from the cabinet, and his opposition to the treaty became useless. On August 24, Washington signed the treaty.

The anger over the Jay Treaty calmed down for a while. By late 1796, Federalists had gathered twice as many signatures in favor of the treaty as against it. Public opinion had shifted to support the treaty. The next year, the debate flared up again when the House of Representatives got involved. The new debate was not just about the treaty's merits. It was also about whether the House had the power to refuse to provide money for a treaty already approved by the Senate and signed by the president.

The House asked the president to hand over all documents related to the treaty. Washington refused, using what became known as executive privilege. He insisted the House did not have the power to block treaties. A heated debate followed. Washington's strongest opponents in the House publicly called for his impeachment. Through it all, Washington used his influence and political skills to gain public support for his position. Federalists strongly pushed for the treaty's passage. On April 30, the House voted 51–48 to approve the necessary funding for the treaty. Jefferson's supporters continued their campaign against the treaty and "pro-British Federalist policies" in the 1796 elections. The treaty pushed the new nation away from France and towards Great Britain. The French government believed it violated the 1778 Franco-American treaty. They also thought the U.S. government accepted the treaty despite strong public opposition.

Conflict with France

Adams's time as president was marked by arguments about America's role in the growing conflict in Europe. Britain and France were at war. In the 1796 elections, the French supported Jefferson for president. They became even more aggressive when he lost. Still, when Adams took office, many Americans still felt strongly positive about France. This was because France had helped during the Revolutionary War.

Adams hoped to keep good relations with France. He sent a group to Paris, including John Marshall, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, and Elbridge Gerry. They were to ask for payment for French attacks on American ships. When the envoys arrived in October 1797, they waited for days. Then, they had only a 15-minute meeting with French Foreign Minister Talleyrand. After this, three of Talleyrand's agents met the diplomats. Each agent refused to talk about diplomacy unless the United States paid huge bribes. One bribe was for Talleyrand personally, and another for France. The Americans refused to negotiate under these terms. Marshall and Pinckney went home, while Gerry stayed.

In April 1798, Adams publicly revealed Talleyrand's schemes to Congress. This sparked public anger at the French. Democratic-Republicans doubted the government's story of what became known as the "XYZ affair." Many of Jefferson's supporters tried to undermine Adams's efforts to defend against the French. Their main fear was that war with France would lead to an alliance with England. This, they thought, could allow Adams to push his domestic agenda, which they saw as leaning towards monarchy. Many Federalists, especially the very conservative ones, deeply feared the extreme influence of the French Revolution. Money also caused division between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Federalists wanted financial ties with England, while many Democratic-Republicans feared the power of English lenders.

Quasi-War (1798-1800)

President Adams saw no benefit in joining the British-led alliance against France. So, he chose a strategy where American ships would harass French ships. This was enough to stop French attacks on American interests. This started an undeclared naval war known as the Quasi-War.

Facing the threat of invasion from stronger French forces, Adams asked Congress to allow a major expansion of the navy and the creation of a 25,000-man army. Congress approved a 10,000-man army and a moderate expansion of the navy. At the time, the navy had only one unarmed customs boat. Washington was made the senior officer of the army. Adams reluctantly agreed to Washington's request that Hamilton be the army's second-in-command. It became clear that Hamilton was truly in charge due to Washington's old age. Adams was angry, saying Hamilton was "a proud Spirited, conceited, aspiring Mortal always pretending to Morality." Because of his support for expanding the navy and creating the United States Department of the Navy, Adams is often called "the father of the American Navy."

Led by Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert, the navy had several successes in the Quasi-War. This included capturing L'Insurgente, a powerful French warship. The navy also opened trade with Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), a rebellious French colony in the Caribbean. Adams resisted making the war bigger, even against the wishes of many in his own party. His continued support for Elbridge Gerry, a Democratic-Republican he had sent to France, frustrated many Federalists. Hamilton's influence in the War Department also widened the gap between Adams's and Hamilton's Federalist supporters. At the same time, creating a large standing army worried many people. This played into the hands of the Democratic-Republicans.

In February 1799, Adams surprised many by announcing he would send diplomat William Vans Murray on a peace mission to France. Adams delayed sending a group while he waited for several U.S. warships to be built. He hoped this would change the balance of power in the Caribbean. To the dismay of Hamilton and other extreme Federalists, the group was finally sent in November 1799. The president's decision to send a second group to France caused a bitter split in the Federalist Party. Some Federalist leaders began looking for someone other than Adams for the 1800 presidential election.

The chances for peace between the U.S. and France improved with the rise of Napoleon in November 1799. Napoleon saw the Quasi-War as a distraction from the ongoing war in Europe. In the spring of 1800, the group sent by Adams began talking with the French group, led by Joseph Bonaparte.

The war ended in September when both sides signed the Convention of 1800. But the French refused to recognize the end of the Treaty of Alliance of 1778, which had created a Franco-American alliance. The United States gained little from the agreement other than stopping fighting with the French. But the timing of the agreement was lucky for the U.S. The French would get a temporary break from war with Britain in the 1802 Treaty of Amiens. News of the agreement did not reach the United States until after the election. Adams was able to get the Senate to approve the agreement in February 1801, overcoming opposition from some Federalists. After the war ended, Adams sent the emergency army home.

Disputes with Spain

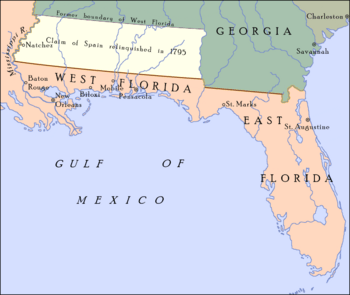

Spain fought the British as an ally of France during the Revolutionary War. But it did not trust the idea of republicanism and was not officially an ally of the United States. Spain controlled Florida and Louisiana, which were south and west of the United States. Americans had long known how important navigation rights on the Mississippi River were. It was the only realistic way for many settlers in the trans-Appalachian lands to ship their goods to other markets, including the Eastern Seaboard of the United States.

Even though they fought a common enemy in the Revolutionary War, Spain saw American expansion as a threat to its empire. To stop American settlement of the Old Southwest, Spain denied the U.S. navigation rights on the Mississippi River. It also gave weapons to Native Americans. Spain also tried to get friendly American settlers to move to the sparsely populated areas of Florida and Louisiana. Spain worked with Alexander McGillivray and signed treaties with the Creeks, Chickasaws, and Choctaws. These treaties aimed to make peace among the tribes and ally them with Spain. But the pan-Indian alliance was not stable. Spain also bribed American General James Wilkinson in a plan to make much of the southwestern United States break away. But nothing came of it.

In the late 1780s, Georgia wanted to secure its land claim west of the Appalachians. It also wanted to meet citizen demands to develop the land. The territory claimed by Georgia, called the "Yazoo lands," stretched west from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River. It included most of present-day Alabama and Mississippi. The southern part of this region was also claimed by Spain as part of Spanish Florida. One of Georgia's efforts to achieve its goals was a 1794 plan developed by Governor George Mathews and the Georgia General Assembly. This soon became a major political scandal, known as the Yazoo land scandal.

After Washington issued his 1793 Proclamation of Neutrality, he worried that Spain might work with Britain to cause trouble in the Yazoo lands against the U.S. They might use the opening of trade on the Mississippi as a lure. At the same time, in mid-1794, Spain was trying to get out of its alliance with the British and make peace with France. As Spain's prime minister, Manuel de Godoy, was trying to do this, he learned of John Jay's mission to London. He became concerned that those talks would lead to a British-American alliance and an invasion of Spanish lands in North America. Feeling the need for better relations, Godoy asked the U.S. government for a representative to negotiate a new treaty. Washington sent Thomas Pinckney to Spain in June 1795.

Eleven months after the Jay Treaty was signed, the United States and Spain agreed to the Treaty of San Lorenzo, also known as Pinckney's Treaty. Signed on October 27, 1795, the treaty aimed for peace and friendship between the U.S. and Spain. It set the southern border of the U.S. with the Spanish colonies of East Florida and West Florida. Spain gave up its claim to the part of West Florida north of the 31st parallel. It also set the western U.S. border along the Mississippi River from the northern U.S. to the 31st parallel.

Perhaps most importantly, Pinckney's Treaty gave both Spanish and American ships unrestricted navigation rights along the entire Mississippi River. It also allowed American ships to transport goods through the Spanish port of New Orleans without paying duties. This opened up much of the Ohio River basin for settlement and trade. Farm products could now flow on flatboats down the Ohio River to the Mississippi and on to New Orleans. From there, the goods could be shipped around the world. Spain and the United States also agreed to protect each other's ships anywhere within their control. They also agreed not to detain or stop each other's citizens or vessels.

The final treaty also canceled Spanish promises of military support to Native Americans in the disputed regions. This greatly weakened the tribes' ability to resist people moving onto their lands. The treaty was a major victory for the Washington administration. It also calmed many critics of the Jay Treaty. It encouraged American settlers to continue moving west by making the frontier areas more attractive and profitable. The region Spain gave up its claim to was organized by Congress as the Mississippi Territory on April 7, 1798.

As war between France and the United States seemed possible, Spain was slow to put the terms of the Treaty of San Lorenzo into action. Shortly after Adams became president, Senator William Blount's plans to drive the Spanish out of Louisiana and Florida became public. This made relations between the U.S. and Spain worse. Francisco de Miranda, a Venezuelan patriot, also tried to get support for an American attack against Spain, possibly with British help. Adams rejected Hamilton's ideas for taking Spanish territory and refused to meet with Miranda, stopping the plot. Having avoided war with both France and Spain, the Adams administration oversaw the carrying out of the Treaty of San Lorenzo.

Barbary Pirates

After the Revolutionary War ended, the ships of the Continental Navy were gradually sold off, and their crews were sent home. The frigate Alliance, which fired the last shots of the war in 1783, was also the last ship in the Navy. Many in the Continental Congress wanted to keep the ship in service. But a lack of money for repairs and a change in national priorities eventually won out. The ship was sold in August 1785, and the navy was disbanded.

Around the same time, American merchant ships in the Western Mediterranean Sea and Southeastern North Atlantic started having problems with pirates. These pirates operated from ports along North Africa's so-called Barbary Coast (Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis). In 1784–85, Algerian pirate ships seized two American ships (Maria and Dauphin) and held their crews for ransom. Thomas Jefferson, who was then the Minister to France, suggested an American naval force to protect American shipping in the Mediterranean. But his ideas were initially ignored. Later suggestions from John Jay to build five 40-gun warships were also met with indifference.

Starting in late 1786, the Portuguese Navy began blocking Algerian ships from entering the Atlantic Ocean through the Strait of Gibraltar. This gave temporary protection for American merchant ships. However, in 1793, the Barbary pirates began to roam the Atlantic. They soon captured 11 American vessels and over a hundred sailors.

In response to continued attacks on American shipping, Washington asked Congress to create a permanent navy. After a strong debate, Congress passed the Naval Armament Act on March 27, 1794. This law allowed the building of six frigates. These ships were the first ships of what eventually became the present-day United States Navy. Soon after, Congress also approved money to make a treaty with Algiers and to pay ransom for Americans held captive. At that time, 199 Americans were alive, including a few survivors from the Maria and the Dauphin. The final cost for the return of the captives and peace with Algiers was $642,000, plus $21,000 in annual tribute. The president was not happy with the agreement, but he knew the U.S. had little choice. Treaties were also made with Tripoli in 1796 and Tunis in 1797. Each treaty required an annual U.S. payment for protection from attack. The new Navy would not be used until after Washington left office. The first two frigates completed were: United States, launched May 10, 1797; and Constitution, launched October 21, 1797.

Images for kids

-

President George Washington directed U.S. foreign policy from 1789 to 1797

-

The storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, marked the beginning of the French Revolution. Washington kept the United States neutral during the conflict.

-

Scene depicting the February 9, 1799 engagement between the USS Constellation (left) and the L'Insurgente (right) during the Quasi-War.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |