History of early Islamic Tunisia facts for kids

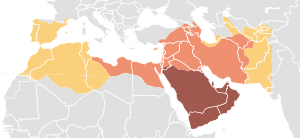

The History of early Islamic Tunisia tells the story of how the Arabs arrived in North Africa, bringing their language and the religion of Islam. This happened as the Umayyad Caliphate expanded its power, especially against the Byzantine Empire. The local Berbers eventually became Muslims. They might have felt a connection with the Arabs because of similar ways of life, like herding animals.

The first local Islamic rulers in Tunisia were the Aghlabids. They were mostly from an Arab tribe. During their time, important parts of Islamic civilization were set up. Even though many Berbers accepted Islam, they often didn't want to be ruled by Arabs. This led to the creation of the Rustamid kingdom after a big revolt by a group called the Kharijites. Later, the Fatimids, a Shia Muslim group, rose to power in Tunisia. They were inspired by people from the east but were mostly made up of local Berbers. The Fatimids then conquered Egypt and other lands to the east, creating their own caliphate there.

Contents

Umayyad Caliphate in Ifriqiya

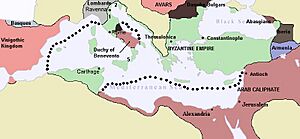

After the first four rightly-guided caliphs (leaders after the Prophet Muhammad), the Umayyad family took control of the new Muslim state. The Umayyad Caliphate (661-750) ruled from Damascus. Their first Caliph, Mu'awiya, led Muslim armies in their ongoing fight with the Byzantine Empire. Years before, the Byzantine lands of Syria and Egypt had already been taken by Muslim forces. Under Mu'awiya, the Umayyads saw that the lands west of Egypt were important for their military plans. This is how the long effort to conquer North Africa began.

Islamic Conquest of North Africa

In 670, an Arab Muslim army led by Uqba ibn Nafi entered the region of Ifriqiya. This was a new Arabic name for the old Roman Province of Africa. The Arabs marched inland, avoiding the strong Byzantine forts along the coast. In the drier southern part of Ifriqiya, they built their main base, the city of Kairouan. They also started building its famous Mosque.

From 675 to 682, Dinar ibn Abu al-Muhadjir took over the invasion. The main resistance came from armed Berber forces. These Berbers were mostly Christian farmers, led by Kusaila. In the late 670s, the Arab armies defeated them and captured Kusaila.

In 682, Uqba ibn Nafi returned as commander. He defeated another group of Berbers near Tahirt (in modern Algeria). Then he marched west, winning many battles, until he reached the Atlantic coast. It is said he wished there were more lands to conquer for Islam. Stories from Uqba's campaigns became famous throughout the Maghreb.

However, Kusaila, the captured Berber leader, escaped. He then led a new Berber uprising. This stopped the conquest and led to the death of Uqba. Kusaila then formed a larger Berber kingdom. But Zuhair b. Qais, Uqba's deputy, gathered Zanata Berber tribes from Cyrenaica to fight for Islam. In 686, he defeated and ended Kusaila's new kingdom.

Under Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (685-705), who ruled from Damascus, the Umayyad conquest of North Africa was almost finished. A new army of 40,000 soldiers was put together in Egypt, led by Hassan ibn al-Nu'man. The Byzantines, who were weaker, had managed to strengthen their positions a bit. The Arab Muslim army crossed Cyrene and Tripoli easily. Then they quickly attacked and captured Carthage.

But the Berbers continued to fight hard. They were now led by a woman from the Jarawa tribe, whom the Muslims called "the prophetess" (al-Kahina). Her real name was Damiya. Near the Nini river, an alliance of Berbers under Damiya strongly defeated the Muslim armies led by al-Nu'man. He escaped back east to Cyrenaica. The Byzantines used this Berber victory to take back Carthage.

Unlike the Berber leader Kusaila ten years earlier, Damiya did not create a large state. She seemed happy to rule only her own Jawara tribe. Some people think that Damiya believed the Arabs were mainly interested in taking treasure. So, she started to destroy and loot the region herself. This was probably to make it seem less attractive to raiders looking for war spoils. Of course, this also made her forces very unpopular with the local people. But she did not attack the Muslim base at Kairouan.

From Egypt in 698, Caliph 'Abdul-Malik sent more soldiers to al-Nu'man, who then re-entered Ifriqiya. Damiya told her two sons to join the Arabs, but she continued to fight. She lost the battle, and al-Nu'man won. It is said that Damiya was killed at Bir al-Kahina (well of the prophetess) in the Auras mountains.

In 705, Hassan b. al-Nu'man attacked Carthage. He defeated and destroyed it. The nearby city of Utica suffered a similar fate. At Tunis, a small town from the Punic era near the ruins of Carthage, al-Nu'man built a naval base. Muslim warships began to control the nearby Mediterranean coast. Because of this, the Byzantines finally left North Africa. The Arabs called the region al-Maghrib, meaning "the sunset land" or "the west."

Al-Nu'man was then replaced by Musa ibn Nusair, who mostly finished the conquest of al-Maghrib. Ibn Nusair took the city of Tangier on the Atlantic coast. He appointed the Berber leader Tariq Abu Zara as its governor. Tariq would later lead the Muslim conquest of Hispania (Spain), which began in 711.

Berber Role in the Conquest

The Berbers, also called the Amazigh, became Muslims in large numbers. They also started to be treated equally with the Arabs under Islamic law. Historians say that the Berbers played a very important role in the west, similar to how Arabs played a role elsewhere in the Islamic world. For centuries, Berbers lived as semi-nomadic people in or near dry lands, keeping their unique identity, much like the Arabs.

Some historians argue that the Berbers at first just joined the successful Arab Muslim armies. They believe the Berbers should have chosen a more unique path for themselves. However, Professor Abdallah Laroui believes that the Berbers did create an independent role for themselves. He says that from the first century BC to the eighth century AD, the Berbers always tried to rebuild their own kingdoms, like those from the Carthaginian period. He sees this as a success. Laroui compares ancient Berber kings like Masinissa to later Berber kingdoms like the Rustamids, Almoravids, Almohads, Zirids, and Hafsids.

By choosing to ally with the newcomers from Arabia, instead of with nearby Europe (which they remembered from Roman times), the Berbers made a clear decision about their future. Their hearts were open to Islam because they saw it as a way to gain freedom and independence for their land.

The languages spoken by the Semitic Arabs and the Berbers are both part of the same world language family, the Afro-Asiatic family. This shared language background might have helped them connect.

Long before and after the Islamic conquest, there was a popular idea of a strong cultural link between Berbers and the Semitic people of the Levant (Middle East). This idea might have made it easier for Berbers to demand equal treatment with the Arab invaders within Islam. Later, in the medieval Maghrib, people even made up fake family trees claiming that Berbers came from ancient Yemen. But these fake origins were later dismissed by famous scholars like Ibn Hazm and Ibn Khaldun.

From Cyrenaica to al-Andalus (Spain), the Berbers, who had adopted some Arab ways, stayed in touch with each other for centuries. They shared a common culture. For example, while most Muslim scholars elsewhere followed the Hanafi or Shafi'i schools of law, some Berbers in the west chose the Maliki madhhab (school of law) and developed it in their own way. Other Berbers chose the revolutionary Kharijite branch of Islam and used it to end Umayyad Arab rule in the Berber lands. As Berbers became Muslims, the Arab settlers among them also adopted some Berber customs.

Another reason Berbers converted was that early Islamic rules were not too strict. Also, they could join the armies of conquest and share in the spoils of war. A few years later, in 711, the Berber leader Tariq ibn Ziyad led the Muslim invasion of the Visigothic Kingdom in Spain. Many Arabs who settled in al-Maghrib were also religious and political rebels. They were often Kharijites who opposed the Umayyad rulers in Damascus. They believed in equality, which was popular among North African Berbers who disliked Arabs acting superior.

The Arab conquest and the Berbers becoming Muslim happened after centuries of religious conflict in the old Roman Empire's Africa Province. The Donatist split within Christianity had caused divisions, often between rural Berbers and the more urban Roman church. Also, the Vandal Kingdom (439-534), who took over from the Romans, also caused religious division by trying to force their Arian form of Christianity on others.

After the conquest and widespread conversion, Ifriqiya became a natural center for an Arab-Berber Islamic government in North Africa. It was a hub for culture and society. Ifriqiya had the most developed cities, trade, and farming, which were essential for the new Islamic project.

Aghlabid Emirate under Abbasids

How the Aghlabids Started

Just before the Umayyad Caliphate in Damascus fell (661-750), revolts by Kharijite Berbers in Morocco caused problems across the entire Maghrib (739-772). The Kharijites didn't create strong, lasting governments. However, the small Rustamid kingdom did survive (controlling southern Ifriqiya). The Berber Kharijite revolt changed the political situation. It became impossible for the Caliphs in the East to directly rule Ifriqiya, even after the new Abbasid Caliphate was quickly set up in Baghdad in 750. Also, after a few generations, a local Arab-speaking upper class grew in Ifriqiya. They didn't like the distant caliphate interfering in their local matters.

The Arab Muhallabids (771-793) were given a lot of freedom by the Abbasids to govern Ifriqiya. One of these governors was al-Aghlab ibn Salim (ruled 765-767), who was an ancestor of the Aghlabids. Decades later, Muhallabid rule ended. A small rebellion in Tunis grew bigger and spread to Kairouan. The Caliph's governor couldn't restore order.

Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab, a local leader and son of al-Aghlab ibn Salim, led a well-trained army. He managed to bring back stability in 797. Later, he asked the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid if he could rule Ifriqiya as his own land, passed down through his family, with the title of amir (prince). The caliph agreed in 800. After that, the Abbasid caliphs received money each year, and their authority was mentioned in Friday prayers. But their control was mostly symbolic. For example, in 864, the Caliph al-Mu'tasim "required" a new part to be added to the Zaituna Mosque near Tunis.

Aghlabid Rule and Society

Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab (ruled 800-812) and his family, known as the Aghlabids (800-909), ruled Ifriqiya. The Aghlabids were mainly from an Arab tribe called the Bani Tamim. At that time, there were about 100,000 Arabs in Ifriqiya, but the Berbers were the large majority. The Aghlabid army was made up of: (a) Arab warriors who had recently arrived or were descendants of earlier invaders, (b) local people who had become Muslim and spoke both Arabic and local languages (called Afariq), most of whom were Berbers, and (c) black slave soldiers from the south. The black soldiers were the ruler's last line of defense.

The Aghlabids came to power by using force and negotiation to control the people and keep order after a time of trouble. In theory, they ruled for the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad. The Caliphate's good name helped the Aghlabids gain authority among the people of Ifriqiya. However, the Aghlabid government was not popular. Even though they brought peace, stability, and economic growth, and built impressive public projects, there was a lot of political disagreement. This wasn't just among Berbers. Many in the Arab-speaking upper class disliked the Aghlabids for several reasons.

First, Arab officers in the army were unhappy with the government's right to rule. Or they used this as an excuse to be disloyal. This general lack of obedience meant that arguments within the military sometimes turned into public fights. Their hidden dislike also showed when army groups started demanding money directly from the people. A dangerous revolt within the Arab army (the jund) broke out near Tunis and lasted from 824 to 826. The Aghlabids had to retreat south towards the Sahara. They were only saved by getting help from the Kharijite Berbers of the Jarid region. Later, another revolt in 893 (said to be caused by the cruelty of Ibrahim II Ibn Ahmad, the ninth Aghlabid amir) was put down by the black soldiers.

Second, Muslim scholars (ulema or clerics) disapproved of the Aghlabid rulers. Religious people were upset by the rulers' un-Islamic way of life. The Aghlabids often lived lives of pleasure, ignoring the strong religious feelings of many in the new Muslim community. This was especially important because their rivals, the Rustamid kingdom (mostly Berber), often criticized the Aghlabids for not being strict enough in their Islamic practices. Another problem was that Aghlabid tax policies were not approved by the main Maliki school of law. Opponents also criticized how the Aghlabids treated Berbers who had become Muslim (called mawali), as if they were still non-believers. The Islamic idea of equality for all, regardless of race (Arab or Berber), became a key principle of the mainstream Sunni movement in the Maghrib. This was developed in Kairouan by the Maliki school of law. These Islamic principles were at the heart of the dislike many people in Ifriqiya felt towards any rule by the Caliph from the East. They also helped fuel anti-Aghlabid feelings.

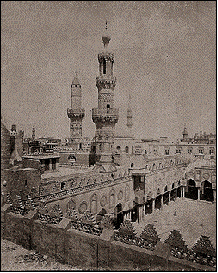

To make up for their actions, the Aghlabid rulers made sure mosques were built or improved. For example, in Tunis, they worked on the Al-Zaytuna Mosque (Mosque of the Olive), which later became home to its famous university. They also built mosques in Kairouan and Sfax. A well-known ribat (a fortified military monastery) was built at Monastir, and another at Susa (in 821 by Ziyadat Allah I). Here, Islamic warriors were trained.

In 831, Ziyadat Allah I (ruled 817-838), son of the founder Ibrahim, launched an invasion of Sicily. The commander was Asad ibn al-Furat, a religious judge (qadi). This military adventure was called a jihad (holy war). It was successful, and Palermo became the capital of the captured region. Later, raids were made against the Italian peninsula. In 846, Rome was attacked, and the Basilica of St. Peter was looted. By planning the invasion of Sicily, the Aghlabid rulers managed to unite two rebellious groups (the army and the clergy) in a common effort against outsiders. Later Islamic rulers in Sicily broke away from Ifriqiya. Their own Sicilian Kalbid dynasty (948-1053) ruled the now independent Emirate.

The invasion of Sicily helped stabilize the political situation in Ifriqiya. The region was relatively peaceful during its middle period. However, in its final years, the dynasty destroyed itself. The eleventh and last amir, Ziyadat Allah III (ruled 902-909), felt unsafe after his father's murder. He ordered his rival brothers and uncles to be killed. This happened during attacks by the newly powerful Fatimids (see below) against the Aghlabid lands.

Aghlabid Government and Economy

In the Aghlabid government, important positions were usually given to "princes of the blood," who could be trusted. The job of Qadi (religious judge) of Kairouan was given "only to outstanding people known for their carefulness even more than their knowledge." However, the administrative staff were made up of loyal helpers (mostly recent Arab and Persian immigrants) and the local bilingual Afariq (mostly Berbers, including many Christians). The Islamic state in Ifriqiya was similar in many ways to the government structure in Abbasid Baghdad. Aghlabid officials included the vizier (prime minister), the hajib (chamberlain), the sahib al-barid (master of posts and intelligence), and many kuttab (secretaries) for things like taxes, money, the army, and letters. Leading Jews formed a small, important group. Like in earlier times (for example, under Byzantine rule), most of the people were rural Berbers. They were not fully trusted because of their Kharajite or similar rebel tendencies.

Kairouan (or Qayrawan) became the cultural center not only of Ifriqiya but of the entire Maghrib. A type of book popular then, called tabaqat (about handling documents), gives us a glimpse into the lives of the elite in Aghlabid Ifriqiya. One such book was Tabaqat 'ulama' Ifriqiya (Classes of Scholars of Ifriqiya) by Abu al-'Arab. Among the Sunni Muslim scholars (ulema), two learned jobs became very important: (a) the faqih (plural fuqaha) or legal expert; and (b) the ābid or religious ascetics.

The fuqaha gathered in Kairouan, which was the legal center for all of al-Maghrib. At first, the more open Hanafi school of Muslim law was common in Ifriqiya. But soon, a strict form of the Maliki school became dominant. In fact, it became the only widespread madhhab (school of law), not just in Kairouan, but throughout North Africa. The Maliki school of law continued to be the legal standard throughout the Maghrib (despite some big interruptions) and still is today.

The Maliki madhhab was brought to Ifriqiya by the legal expert Asad ibn al-Furat (759-829). However, he was known to switch between the Hanafi and Maliki schools. An important law book called Mudawanna, written by his student Sahnun ('Abd al-Salam b. Sa'id) (776-854), provided a simple version of North African Malikism for practical use. This happened during the time when Maliki legal ideas won out against its rival, the Hanafi. Abu Hanifa (700-767), who started the Hanafi school, created laws that were perhaps better suited for Baghdad, a big imperial capital. On the other hand, Malik ibn Anas (716-795) started the school named after him in the smaller, rural city of Medina. By choosing the then less common Maliki school, the legal experts of Kairouan probably gained more freedom in shaping the legal culture of the Maghrib.

The Maliki legal experts often disagreed with the Aghlabids. They were unhappy with the Arab rulers' poor personal moral behavior. They also disagreed about taxes on farming (a new fixed cash tax instead of the traditional tithe, which was a share of the crops). The offensive cash tax on crops was introduced by the second amir, 'Abdullah ibn Ibrahim (812-817). Furthermore, the Maliki fuqaha were generally seen as supporting local independence. This meant they were in favor of the Berbers' interests by blocking possible interference in Ifriqiya's affairs and filtering out foreign influence that might come from the central Arab power in the East.

Besides legal experts, there was another group of Muslim scholars (ulema), who were scholars and ascetics. The most famous of these ābid was Buhlul b. Rashid (died 799). He was said to dislike money and refused the job of grand judge. His fame spread throughout the Islamic world. Because of their piety and independence, the ābid gained social respect and a voice in politics. Some scholars would speak for the cities, criticizing the government's financial and trade decisions. Although very different, the status of the ābid is somewhat related to the much later figure of the Maghribi saint, the wali. These saints were believed to have baraka (spiritual power) and became objects of worship. Their tombs were places of pilgrimage.

Economically, Ifriqiya did very well under Aghlabid rule. Many improvements were made to existing water systems to help grow olive trees and other crops (oils and grains were exported). They also irrigated royal gardens and provided water for livestock. Roman aqueducts that supplied towns with water were rebuilt under Abu Ibrahim Ahmad, the sixth amir. In the Kairouan region, hundreds of basins were built to store water for raising horses.

Trade started again under the new Islamic government. For example, by sea, especially to the east, with the Egyptian port of Alexandria as a main destination. Also, better trade routes connected Ifriqiya with the inner parts of the continent, the Sahara and the Sudan. These regions were regularly included in Mediterranean trade for the first time during this period. It seems that camels were not widely used in these dry regions until the fourth century. It wasn't until several centuries later that their use in the Saharan trade became common. Now, this long-distance overland trade truly began. The desert city of Sijilmasa near the Atlas mountains in the far west served as a main trading point for things like salt and gold. For Ifriqiya, Wargla was the main desert contact for Gafsa and the more distant Kairouan. In addition, Ghadames, Ghat, and Tuat were stops for the Saharan trade to Aghlabid Ifriqiya.

A strong economy allowed for a fancy and luxurious court life. New palace cities like al-'Abbasiya (809) and Raqada (877) were built. These were the new homes of the ruling amir. The architecture of Ifriqiya was later copied further west in Fez, Tlemcen, and Bougie. The Aghlabid government purposely placed these palace cities outside the influence of Kairouan. Kairouan had become controlled by Muslim religious institutions, which were independent of the amir's power. However, Ifriqiya generally kept its leading role in the region during the Aghlabid Dynasty (799-909). This was due to its peace, stability, recognized cultural achievements, and wealth.

Independent Berber Islam

The Kharijite Revolt

The Rustamid state started because of the Berber Kharijite (Arabic: Khawarij) revolt (739-772). This revolt was against the new Arab Sunni Muslim power that was being set up across North Africa after the Islamic conquest. The Kharijite movement began in Mesopotamia. It was a protest against the fourth caliph Ali, who agreed to negotiate during a Muslim civil war (656-661) even though his army was winning. As a result, some of his soldiers left his camp, which is why they were called Khawarij ("those who go out").

Originally, they were very strict. They believed that being part of the Muslim community (ummah) meant having a perfect soul. If someone sinned, it caused a split from other believers, and the sinner became an apostate (someone who leaves their religion). Their leader had to be perfect and could be non-Arab. The Kharijite movement never achieved lasting success, but it kept fighting. Today, only its Ibadi branch remains, with small groups in isolated places throughout the Muslim world. The Ibadis are the main group in Oman.

In the Maghrib, the new Arab Islamic government placed un-Islamic taxes on Muslim Berbers. They charged the kharaj (land tax) and the jizya (poll tax), which were only meant for non-Muslims. This caused widespread armed resistance, led by Kharijite Berbers. This widespread fight included victories, such as the "battle of the nobles" in 740. Later, the Kharijites became divided and were eventually defeated after several decades. Arab historians say that the 772 defeat of the Kharijite Berbers by an Abbasid army near Tripoli was "the last of 375 battles" the Berbers had fought for their rights against armies from the East. Yet, the Kharijites continued under the Rustamids. Even today, small communities of this religious minority still exist across North Africa.

The Rustamid Kingdom

A group of Kharijites who survived established a state (776–909) under the Rustamids. Their capital was at Tahert (located in the mountains southwest of modern Algiers). Besides the lands around Tahert, Rustamid territory mostly included the high, dry plains or "pre-Sahara." This area forms the border between the wetter coastal regions of the Maghrib and the dry Sahara desert. Their territory stretched in a narrow strip eastward as far as Tripolitania and Jebel Nefusa (in modern Libya). In between lay southern Ifriqiya, where Rustamid lands included the oases of the Djerid, with its salt lakes (chotts), and the island of Djerba. This long, narrow geography worked because the Rustamid government was very open-minded. The leader (Imam) didn't so much rule the surrounding tribes as he oversaw them. His authority was recognized rather than forced, and people willingly asked him to help settle disputes. So, this Rustamid territory ran from Tlemcen in the west to Jebel Nefusa in the east.

The people of this pre-Sahara region were called Arzuges in the 3rd century by the Roman army. The Roman military kept Arzugitana separate from the rule of the coastal cities. The fall of Rome "offered new chances for the communities of the pre-Sahara zone and their leaders. It can be seen as a time of rebirth in the region, at least politically." The Arzuges managed to regain their independence.

The Arab Aghlabid emirate in Ifriqiya remained the most powerful state in the region and the Rustamids' neighbors. However, the Aghlabids could not get rid of these remaining Kharijites. Soon, they had to accept Rustamid rule in the pre-Sahara region of the eastern Maghrib. In Hispania, which was now al-Andalus, the Emirs of Córdoba welcomed the Rustamid Berbers. They saw them as natural allies against the Aghlabids, whom Umayyad Córdoba considered agents of the Abbasids.

Tahert was in a good economic location. It was a trading center for goods moving between the Mediterranean coast and the Sahara. During the summer, Tahert became a marketplace where desert and steppe herders traded their animal products for grains grown by local farmers. As the most important Kharijite center, it attracted people from all over the Islamic world, including Persia, where its founder came from. Christians were also welcome. However, tolerance for certain behaviors was low. "Life at Tahert was lived in a constant state of religious excitement."

The founder Ibn Rustam (ruled 776–784) took the title of Imam. While in theory elected by elders, in practice the Imam's position was passed down through the family. The government was based on religious law. The Imam was both a political and a religious leader. Islamic law was strictly followed. The Imam managed the state, law, justice, prayers, and charity. He collected zakah (alms) at harvest time and gave it to the poor and for public works. He appointed the qadi (judge), the treasurer, and the police chief. The Imam was expected to live a simple life and be a skilled religious scholar. He also had to be smart, as disagreements among citizens could turn into religious splits. However, opposing parties in disputes often agreed to mediation. The Khawarij remained tolerant towards "unbelievers."

The remaining Christians in the region (called Afariqa or Ajam by Muslim Arabs) found a tolerant home in Rustamid Tahert. Their community was known as the Majjana. This acceptance "might explain why Ibadi communities grew in areas where there is also evidence that Christianity continued to exist." However, given the ongoing defense of Rustamid independence against "the attacks of the central power" (the Aghlabids), the choice to become Muslim was sometimes "as much a political act as a religious one."

The Rustamids lasted about as long as the Aghlabid emirate. Both states declined and fell to the Fatimids in 909. Kharijites who survived from the Rustamid era eventually became Ibadis. For the most part, they now live in the Djebel Nefousa (western Libya), in the Mzab and at Wargla (eastern Algeria), and on Djerba island in Tunisia.

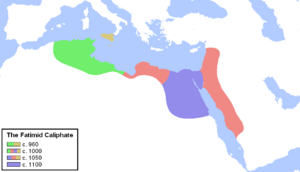

Fatimids: Shi'a Caliphate

In the far west of Ifriqiya, the new Fatimid movement grew stronger. The Fatimids then began to frequently attack the Aghlabid government. This aggressive behavior caused general unrest and made the Aghlabids' political situation even more unstable. The Fatimids eventually captured Kairouan in 909, forcing the last Aghlabid ruler, Ziyadat Allah III, to leave his palace at Raqadda. At the same time, the Rustamid state was overthrown. On the east coast of Ifriqiya, facing Egypt, the Fatimids built a new capital on top of ancient ruins. They named the seaport Mahdiya after their mahdi.

Fatimids' Origins in the Maghrib

The Fatimid movement started locally in al-Maghrib. It was based on the strength of the Kotama Berbers in Kabylia (Setif, south of Bougie, eastern Algeria). The two founders of the movement were recent immigrants from the Islamic east: Abu 'Abdulla ash-Shi'i, originally from San'a in Yemen; and 'Ubaidalla Sa'id, who came from Salamiyah in Syria. These two were religious rebels who came west to al-Maghrib specifically to spread their beliefs. The latter, 'Ubaidalla Sa'id, claimed to be a descendant of Fatimah, the daughter of Muhammad. He would later declare himself the Fatimid Mahdi. Their religious group was the Ismaili branch of the Shia.

By agreement, the first of the two founders to arrive (around 893) was Abu 'Abdulla ash-Shi'i, the Ismaili Da'i (propagandist). He found support among the Kotama Berbers, who disliked the Caliphate in Baghdad. After successfully recruiting and building his organization, Abu 'Abdulla was ready in 902 to send for 'Ubaidalla Sa'ed. After some adventures and being imprisoned by the Aghlabids in Sijilmasa, 'Ubaidalla Sa'ed arrived in 910. 'Ubaidalla Sa'ed then declared himself Mahdi, which means "the guided one." This is an important Islamic title of supreme command. He took the name Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi Billah. He took over leadership of the movement. Later, Abu 'Abdulla was killed in a fight over control.

From the beginning, the Shi'a Fatimid movement wanted to expand eastward towards the heartland of Islam. Soon, the new Mahdi ordered an attack on Egypt by a Fatimid army of Kotama Berbers led by his son al-Qa'im. This happened once in 914 and again in 919. The Fatimids quickly took Alexandria, but both times they lost it to the Sunni Abbasids. Looking for weaknesses, the Mahdi then sent an invasion westward, but his forces had mixed results. Many Sunnis, including the Umayyad Caliph of al-Andalus and the Zenata Berber kingdom in Morocco, strongly opposed him because of his Ismaili Shi'a beliefs. The Mahdi did not follow Maliki law, and he taxed people harshly, causing more resentment. His capital Mahdiya was more of a fort than a grand city. The Maghrib was in chaos, with the Zenata in the west fighting the Sanhaja who supported the Fatimids. Yet, Fatimid authority eventually spread to most of al-Maghrib.

After the Mahdi's death, there was a popular Kharijite revolt in 935, led by Abu Yazid (nicknamed Abu Himara, "the man on a donkey"). Abu Yazid was known to ride around in simple clothes, with his wife and four sons. This Berber revolt, which focused on social justice and Kharijite ideals, gained many followers. By 943, it was causing widespread confusion. The Mahdi's son, the Fatimid caliph al-Qa'im, was besieged in his capital Mahdiya. The situation seemed hopeless until a relief force led by Ziri ibn Manad broke through the siege, bringing supplies and reinforcements for the Fatimids. Eventually, Abu Yazid lost many of his followers and was defeated in battle in 946. This was done by al-Qa'im's son, the next Fatimid caliph, Ishmail, who then took the title Mansur, meaning "the victor." Mansur then moved his home and government to Kairouan. Fatimid rule continued to be attacked by Sunni powers to the west, like the Umayyad Caliphate in Al-Andalus. Nevertheless, the Fatimids prospered.

Conquest of Egypt

In 969, the Fatimid caliph al-Mu'izz sent his best general, Jawhar al-Rumi, to Egypt. Jawhar led a Kotama Berber army. Egypt was then officially under the Abbasid Caliphate. However, since 856, Egypt had been ruled by Turks, specifically the Turkish Ikhshidid dynasty. But the real power had been in the strong hands of the Ethiopian eunuch Abu-l-Misk Kafur for 22 years. When Kafur died in 968, Egypt's leadership became weak and confused. The Fatimids in Ifriqiya, carefully watching these conditions in Misr (Egypt), took the chance to conquer.

Jawhar al-Rumi managed the military conquest without much difficulty. The Shi'a Fatimids then founded al-Qahira (Cairo) ["the victorious" or the "city of Mars"]. In 970, the Fatimids also founded the world-famous al-Azhar mosque, which later became the leading Sunni religious center. Three years later, al-Mu'izz, the Fatimid caliph, decided to leave Ifriqiya for Egypt. He took everything: "his treasures, his administrative staff, and the coffins of his predecessors." This al-Mu'izz was very educated. He wrote Arabic poetry, spoke Berber, studied Greek, and loved literature. He was also a very capable ruler, and he was the one who established Fatimid power in Egypt. Once based there, the Fatimids expanded their lands further, northeast to Syria and southeast to Mecca and Medina. They kept control of North Africa until the late 11th century. From Cairo, the Fatimids had good success, even after losing Ifriqiya, and reigned until 1171. For a time, they became the most powerful force in Islam. They never returned to Ifriqiya. Meanwhile, the Kotama Berbers, tired from their fights for the Fatimids, disappeared from the streets of al-Qahira and later from the life of al-Maghrib.

The Fatimids' western lands were given to Berber rulers who continued to rule in the name of the Shi'a caliphate. The first chosen ruler was Buluggin ibn Ziri, son of Ziri ibn Manad (died 971). Ziri ibn Manad was the Sanhaja Berber chieftain who had saved the Fatimids when they were under siege in Mahdiya by Abu Yazid (see above). The Zirid dynasty would eventually become the independent rulers in Ifriqiya.

|

See also