Jean Batten facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean Batten

|

|

|---|---|

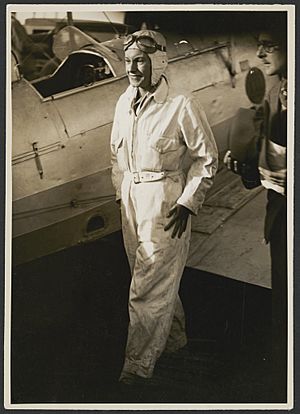

Batten in 1937

|

|

| Born | 15 September 1909 Rotorua, New Zealand

|

| Died | 22 November 1982 (aged 73) Palma, Majorca, Spain

|

| Known for | Record breaking trans-world flights |

| Awards | Commander of the Order of the British Empire Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (France) Order of the Southern Cross (Brazil) |

Jean Gardner Batten CBE OSC (15 September 1909 – 22 November 1982) was a famous New Zealand aviator. Born in Rotorua, she became one of the most famous New Zealanders in the 1930s. She broke many records with her amazing solo flights around the world. In 1936, she made history by flying solo from England all the way to New Zealand for the first time.

Contents

- Jean Batten's Early Life

- Learning to Fly

- Record Flights to Australia

- Touring Australia and New Zealand

- Return to England

- England to Brazil Flight

- Between Flights

- England to New Zealand Flight

- Public Appearances

- Australia to England Flight

- Later Life and Legacy

- Jean Batten's Legacy

- Major Flights and Records

- Images for kids

- See also

Jean Batten's Early Life

Jean Gardner Batten was born on 15 September 1909 in Rotorua, New Zealand. Her father, Frederick Batten, was a dentist, and her mother was Ellen Batten. Jean was the only daughter in the family and had two older brothers.

In 1913, her family moved to Auckland. Jean started school at a private school, but in 1917, she moved to a state school. During the First World War, her father joined the army, and the family had less money. Jean's mother encouraged her to try activities that were often seen as for boys. She took Jean to Kohimarama to watch flying boats at a flight school. Jean later wrote that these visits made her want to fly.

In 1920, Jean's parents separated. This event affected Jean deeply, and she later said she would never get married. After her parents separated, Jean lived with her mother in Howick. In 1922, Jean went to Ladies' College, a boarding school for girls in Remuera. She finished school at the end of 1924. After school, she studied music and ballet, hoping to become a professional pianist or dancer. She even became an assistant teacher at the ballet school.

Learning to Fly

In May 1927, Jean read about Charles Lindbergh's amazing non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean. This made her childhood interest in aviation grow stronger. The next year, Australian pilot Charles Kingsford Smith flew from Australia to New Zealand in his plane, the Southern Cross. Jean's father took her to meet Kingsford Smith in Auckland. When she met him, she told him she wanted to learn to fly, but he didn't take her seriously. Jean felt embarrassed and promised her mother she would learn to fly.

In 1929, she took a flight with Kingsford Smith while on holiday in Sydney. When she returned to Auckland, she told her father she wanted to become a pilot. Her father did not approve, as he thought it was not a suitable job for a woman. He refused to pay for her flying lessons.

Jean, with her mother's encouragement, decided to go to England to learn to fly. She sold her piano to help pay for the trip for herself and her mother. Jean and her mother left New Zealand in early 1930 and traveled to England.

In London, Jean joined the London Aeroplane Club (LAC) at Stag Lane Aerodrome. She felt she had a natural talent for flying. However, she crashed her plane during an early solo flight, though she never spoke about it later. In May, Amy Johnson, another pilot from the LAC, completed the first solo flight by a woman from England to Australia. Jean wanted to beat Johnson's record.

Jean earned her pilot's A licence on 5 December 1930. She didn't have much money, so she could only fly for short periods a few times a week. Her father found out she was flying and stopped sending her money. Despite this, Jean was still determined to beat Amy Johnson's record. She returned to New Zealand in January 1931, hoping her family would help her get money for her flying dreams.

Back in New Zealand, Jean started flying lessons again at the Auckland Aero Club. She soon got her New Zealand A pilot's licence. She also became friends with Fred Truman, a pilot in the Royal Air Force (RAF). He helped her with navigation lessons.

Jean still wanted to make a record flight and looked for someone to sponsor her. In July, she returned to England to get her B licence, which would allow her to become a commercial pilot. This would make her more believable to sponsors. Fred Truman lent her £500 to pay for her training. Jean got her B licence in December 1932.

Record Flights to Australia

Jean learned how to fix planes and their engines, which was very useful. She met Victor Dorée, who bought her a Gipsy Moth plane. Jean planned to use this plane to beat Amy Johnson's record for flying from England to Australia solo.

First Attempt

Jean started her flight to Australia, a trip of about 10,500 miles (16,900 km), on 9 April 1933, from Lympne Aerodrome. She had prepared well, getting visas and planning her stops for fuel. Her departure was widely reported in the news.

Her first flight was ten hours to Rome. She then flew to Naples and then to Athens. On 11 April, she flew to Aleppo, in Syria, facing strong winds and clouds. Later that day, flying to Baghdad, in Iraq, she flew into a sandstorm. She had to land her plane in a brief break in the storm. After an hour, she continued to Baghdad.

Jean flew on to Basra and then Bushehr, in Iran. She continued to Jask and then to Karachi. After leaving Jask, she ran into another sandstorm. Her Gipsy Moth got stuck in mud when she had to land. With help from villagers, the plane was pulled out, but the propeller was damaged. She traveled to Karachi to get a new propeller. The next day, she took the new propeller back to her plane. After fixing it, she took off for Karachi.

Before reaching Karachi, her engine broke down. A part called a conrod had snapped. She landed safely on a road, but the plane's wings hit a marker, and it flipped over. Luckily, Jean was wearing her harness and was not hurt.

The Castrol oil company helped Jean. Their chairman, Charles Wakefield, paid for her and the damaged plane to return to England.

Second Attempt

Jean still wanted to make her record flight. After looking for sponsors for months, she finally got £400 from Castrol. She bought a second-hand Gipsy Moth plane for £240.

In early 1934, at Brooklands aerodrome, she met Edward Walter, a stockbroker and pilot. They got engaged within a few weeks. Jean started her second attempt on 21 April from Lympne Aerodrome. She flew to Marseilles and then tried to fly to Rome. However, she ran out of fuel over Rome and had to glide to a forced landing. The landing damaged her plane and cut her face.

It took over a week to repair her plane. Walter sent her a propeller from his own plane, and she borrowed a wing from an Italian pilot. Ten days after the crash, Jean flew her repaired plane back to England. She decided to make a third attempt instead of continuing that flight.

Third Attempt

Jean arrived back at Brooklands on 6 May and quickly got ready for her next flight. Walter wanted her to give up, but she convinced him to lend her parts from his plane. Her plane was ready in just two days, and she left on 8 May. She aimed to reach Australia in 14 days.

Jean flew from Lympne Aerodrome to Marseilles, then Rome, and on to Athens. On the third day, she flew to Cyprus. On day four, she planned to fly to Baghdad but ran into sandstorms and had to land at Rutbah Wells. The next day, she flew to Basra, stopping in Baghdad.

The 700-mile (1,100 km) flight from Jask to Karachi on day seven went smoothly. Jean then flew to Calcutta, stopping at Jodphur and Allahabad. At Allahabad, a mechanic didn't properly secure an oil filter, causing her engine to lose oil.

On day ten, she flew to Rangoon. The next day, flying towards Victoria Point, she flew through a heavy storm with strong rain and turbulence. She had to fly using only her instruments because she couldn't see. After nine and a half hours, she landed at Victoria Point, completely soaked.

The rain meant she couldn't continue that day. The next day, she flew to Alor Star and then to Singapore. She was two days ahead of Amy Johnson's record, and the media was very interested in her flight.

The next flight was across the equator to Batavia, in the Dutch East Indies. Her departure the next day was delayed by fog. She refueled at Surabaya and flew to Rambang on Lombok Island. Day 14 involved a two-hour flight to Timor. She had to deal with ash from a volcanic eruption on Flores Island. When she landed at Kupang, she was only 530 miles (850 km) from Australia. Her trip was now front-page news in London.

On 23 May 1934, Jean flew the final part of her journey across the Timor Sea to Darwin. She landed at Darwin's aerodrome at 1:30pm. Her trip time was 14 days, 22 hours, and 30 minutes, beating Amy Johnson's record by over four days.

Jean's record-breaking flight was news all over the world. People were especially interested because of her beauty and charm. After staying the night in Darwin, Jean flew to Sydney, a journey that took a week. At each stop, she was greeted by crowds and received many messages. She announced her engagement to Edward Walter during this trip. Castrol, her sponsor, encouraged her to stay in the public eye.

When Jean flew into Sydney on 30 May, many planes met her over the city's harbor. A crowd of 5,000 people greeted her at the airport. She had many public events for the next four weeks, paid for by the Australian Government. Charles Wakefield of Castrol gave her £1,000.

Touring Australia and New Zealand

Jean traveled to New Zealand by ship because her plane couldn't cross the Tasman Sea. Her plane was shipped over for free. Just like in Australia, large crowds came to greet her in New Zealand. She was honored at many events and received £500 from the New Zealand Government. She toured the country, offering short flights in her plane and giving paid talks. In her hometown of Rotorua, the local Māori tribe, Te Arawa, made her an honorary rangitane (chieftainess).

Jean always praised her mother in her public appearances. When she arrived in Darwin, her first message was to her mother: "Darling, we've done it. The aeroplane, you, me." Her mother soon joined her on the tour of New Zealand.

By the end of her visit to New Zealand in September 1934, Jean had become known as a very skilled and brave pilot. She was a hero and a source of pride for New Zealand. She earned a lot of money from the tour, about £2,500.

Jean returned to Australia and worked as a radio commentator for the MacRobertson Air Race. She had hoped to enter the race herself but couldn't get to England in time. She also published a book about her flight called Solo Flight. While in Sydney, she met Beverly Shepherd, a 23-year-old pilot, and they started a relationship. By March 1935, her engagement to Edward Walter was called off.

Return to England

In April 1935, Jean prepared to fly her Gipsy Moth back to England. She hoped to set a new record for the flight from Australia to England. Beverly Shepherd flew with her part of the way to Darwin. About halfway across the Timor Sea, her engine stopped, and she almost crashed into the sea before restarting it. The engine continued to have problems for the rest of her journey.

Jean mostly followed the same route back to England. She arrived at Croydon, in England, after 17 days and 16 hours. She was the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia and back again. Her return was widely reported. She received the Challenge Trophy for 1934 from the Women's International Association of Aeronautics in the United States.

England to Brazil Flight

Jean wanted to make a record flight from England to South America. No woman had flown solo across the South Atlantic before. The record for the fastest flight from England to Brazil was held by Jim Mollison, at three days and ten hours. Jean decided to try to beat this record.

Jean bought a Percival Gull Six monoplane, which was much faster than her old plane. It had a powerful engine and could fly 2,000 miles (3,200 km) without refueling. She received the plane on her birthday, 15 September.

Jean planned to fly to Casablanca, then to Dakar, in West Africa, and then 1,900 miles (3,100 km) across the South Atlantic to Port Natal in Brazil. She left on 11 November 1935. She made it to Casablanca without any problems. The next day, she flew to Thies, where she had to wait for her fuel to arrive.

After a short nap, Jean left Thies at 4:45am on 13 November. She flew through bad weather and had to fly blind for some time. Her compass was affected by a magnetic disturbance. Despite these problems, she reached the Brazilian coast after 12 and a half hours of flying. She landed at Port Natal after 13 hours and 15 minutes, breaking the solo South Atlantic crossing record by three hours. It took her two days, 13 hours, and 15 minutes to fly from England to Brazil, beating Mollison's record by almost 24 hours. She also set the fastest overall flight time for crossing the Atlantic.

The next day, Jean flew towards Rio de Janeiro. Her plane had a fuel leak, and she had to land on a beach. She found shelter in a nearby village. Search and rescue planes were sent out to find her. After a few hours, she and her plane were found. The Brazilian Air Force helped her with fuel and repaired her propeller. She then continued to Rio.

Jean stayed a week in Rio, attending many events. She was given £500 and made an honorary officer in the Brazilian Air Force. The Brazilian President gave her the Order of the Southern Cross. She then flew to Argentina and Uruguay for more events. She returned to England on 23 December.

Between Flights

After Christmas, Jean flew her Gull back to Hatfield aerodrome. During the flight, she crashed her plane. She blamed an engine failure that forced her to land on South Downs. She got a cut on her head and a concussion, and her plane was damaged. The Gull was taken for repairs. While it was being fixed, she went to Paris and received a gold medal. The French Government also announced they would give her the Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur.

She received more awards, including the Britannia Trophy for the best flight by a British person in 1935, and the Harmon Trophy, which she shared with Amelia Earhart.

Once her Gull was repaired, Jean took her mother on a flying holiday to Spain and Morocco. Back in England, she often attended public events. In June 1936, Jean was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for her services to aviation. King Edward VIII presented her with the award on 14 July.

England to New Zealand Flight

Jean began preparing for another world record flight: from England to New Zealand. She also wanted to beat the men's record for the England-Australia flight. She and her mother went on a long walking trip to get fit, and Jean got all the necessary permits and maps for her route.

Jean left Lympne Aerodrome on the morning of 5 October 1936. She flew to Karachi in two and a half days, making quick stops along the way. She then flew to Akyab, in Burma, and the next day, 9 October, she left early for Alor Star, in British Malaya. She faced bad weather and had to land at Penang instead. The heavy rain was damaging her plane's wings, which needed repairs. She then flew to Singapore. By this time, her total flight time was four days, 17 hours.

She left for Rambang, on Lombok, that night and then to Kupang in Timor. Here, she found that her plane's tailwheel had a flat tire. It took several hours to fix, so she had to delay her flight to Darwin. She left Kupang at dawn on 11 October and arrived at Darwin after four hours of flying. A large crowd was waiting for her. She had some trouble landing, as one of her brakes failed. Her total trip time from England to Australia was five days, 21 hours, setting a new record for a solo flight. Jean's achievement was front-page news around the world.

Delay in Australia

Jean knew she needed to continue to Auckland, New Zealand, which was still about 3,700 miles (6,000 km) away. From Darwin, she flew to Longreach in Queensland, where she spent the night. She then flew to Sydney. She was delayed in Sydney for two days because of bad weather over the Tasman Sea. There was also some concern about her flying a single-engine plane across the Tasman, which was known for difficult weather.

The Australian aviation authorities were worried about her plane's weight with all the fuel needed for the Tasman crossing. However, Jean had a special permit from the British authorities that allowed her plane to carry extra weight.

During the delay, Jean made herself available to the media. She earned £600 for a radio interview and signed deals with newspapers and film companies. She also spent some time with Beverly Shepherd, who was now an airline captain.

Crossing the Tasman Sea

On 16 October, Jean left for New Zealand from the Royal Australian Air Force's airbase at Richmond. The longer runway helped her heavily loaded plane take off. The weather forecast was not perfect. Instead of flying directly to Auckland, she decided to aim for New Plymouth, a slightly shorter distance over the sea, and then fly north to Auckland. Before she left, she told everyone that if she crashed in the Tasman Sea, no one should be sent to look for her. She didn't want anyone else's life to be at risk.

The flight to New Plymouth took nine and a half hours, setting a record for the Trans-Tasman crossing. She flew low to see her direction because of rain clouds. Although there was a crowd at New Plymouth airfield, she didn't land there. Instead, she flew past and continued north to Auckland. She landed just after 5:00pm in front of about 6,000 people. She had set a record of 11 days, 45 minutes for a direct flight from England to New Zealand. This record stood for 44 years. She also set a record of ten and a half hours for the crossing from Sydney to Auckland. Jean later said the cheers from the crowd at Auckland were the "greatest moment in my life."

Jean's amazing flight was reported all over the world. Many people compared her to other famous female pilots like Amy Johnson and Amelia Earhart. She received about 1,700 telegrams from overseas. At a reception in Auckland, the city's mayor announced that a place would be named "Jean Batten Place" in her honor.

Public Appearances

Jean started a publicity tour to earn money. She wanted to cover her flight expenses and save for future flights. On the day she arrived in Auckland, she collected some of the fees from car parking at the airport. Her plane was later displayed in a shop in Auckland, where people paid to see it. She also charged a shilling for her autograph. People raised over £2,000 for her.

However, her tour faced problems because of the exclusive deals she had made with the media in Sydney. This affected public interest and attendance at her talks. Jean also had a disagreement with Fred Truman, who had lent her £500 years earlier. Jean's father helped arrange a meeting where she paid back £250, but the rest was never repaid.

By the time Jean arrived in Christchurch, she was tired and sad because of the low attendance at her talks. She took a rest on medical advice, and the rest of her tour was canceled. She spent most of November resting in the South Island. Her spirits improved when she heard about more honors she would receive. She was awarded the Royal Aero Club's Britannia Trophy again, the Harmon Trophy, and the Segrave Trophy.

At the end of November, Jean traveled to Sydney to meet her mother. While waiting, she reunited with Beverly Shepherd. Once her mother arrived, they returned to New Zealand for three months. Her father also joined them for a time, creating the image of a united family. They spent Christmas in Rotorua, where local Māori honored her again. She was given a chief's kahu huruhuru (feather cloak) and called Hine-o-te-Rangi – "Daughter of the Skies."

In February 1937, Jean and her mother traveled to Sydney to meet Shepherd. Jean wanted to marry Shepherd, but he went missing. The passenger plane he was co-piloting failed to arrive. Jean was involved in the search for the missing aircraft. The wreck was found on 28 February, and Shepherd was among those who had died.

Jean was very sad about Shepherd's death. She stayed out of public life for eight months. In September, she learned that another pilot, Jimmy Broadbent, was going to try to break her record for the England-Australia flight. Jean then announced she would try to break Broadbent's record for the Australia-England flight.

Australia to England Flight

Jean planned to use her Percival Gull for the attempt and had its engine checked. She also exercised to get fit. Her mother went to England to greet her when she arrived. Jean got sponsorship from Frank Packer, a media owner, who agreed to pay her for daily reports. Newspapers called the event a "duel" between Batten and Broadbent. Jean noted that flying from Australia to England was harder because of headwinds.

After a weather delay, Jean started her record attempt from Darwin on 19 October. She flew to Rambang on Lombok Island, refueled, and then flew to Batavia to end her first day. She had flown almost 1,800 miles (2,900 km). She started early the next day, flying to Alor Star. She faced thunderstorms and had to fly using only her instruments. After a short stop, she flew to Rangoon, arriving just 36 hours after starting. She had already flown 3,700 miles (6,000 km).

The next day, she flew 2,150 miles (3,460 km) to Karachi, stopping for fuel at Allahabad. She flew low to avoid headwinds. She was the first solo pilot to fly from Rangoon to Karachi in one day. After a four-hour rest, she continued to Basra, then Damascus, and on to Athens. As she crossed the Mediterranean, she flew through a major storm.

The next flight was planned for Rome, but low clouds forced her to land at Naples instead, where she spent the night. She was so tired that she had to be helped out of her plane. The next morning, 24 October, despite bad weather forecasts, she left for Marseilles. She avoided some storms and landed at Marseilles, then continued to England, landing at Lympne aerodrome in the afternoon. A small, excited crowd cheered her arrival.

Jean completed the flight in 5 days, 19 hours, and 15 minutes. She beat Broadbent's record by more than half a day. She also became the first person to hold the solo record for both the outward (England to Australia) and inward (Australia to England) flights at the same time. This was Jean Batten's last long-distance flight.

Later Life and Legacy

After her last record flight, Jean was celebrated in London. She gave a press conference and was interviewed by BBC television and radio. She attended many banquets and receptions. Madame Tussauds made a wax figure of her, and she met the King and Queen at Buckingham Palace. She was living with her mother in Kensington.

In early 1938, she received the medal of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, which is aviation's highest honor. She was the first woman to receive it. Her autobiography, My Life, was published later that year. She toured continental Europe with her Percival Gull, visiting Paris, Brussels, and Stockholm. In early 1939, she gave talks in Scandinavia and the Baltic States.

With her mother, Jean went on a cruise in the Caribbean. She also took a holiday to Sweden. Just before the start of the Second World War, she was advised not to fly over German airspace when returning to England. She got special permission to fly her Percival Gull back over the North Sea. She arrived back in England on 27 August 1939. This was the last time she flew herself.

During the Second World War, Jean offered her services as a pilot to the Royal Air Force (RAF). She hoped to join the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), which used experienced pilots to move planes. However, she did not join the ATA. Her plane was later taken for war service.

Jean instead became a driver for the Anglo-French Ambulance Corps for a few months. She then worked at a munitions factory in Poole, Dorset. In 1943, she moved to London and worked for the National Savings Committee, encouraging people to donate to the war effort.

After the war, Jean and her mother moved to Jamaica in November 1946. They bought land and built a house called 'Blue Horizon'. They met other famous people there, like Ian Fleming and Noël Coward.

By 1953, Jean and her mother wanted to return to England. They sold their house and land in Jamaica and traveled to Europe. They toured Europe for seven years, staying in budget hotels. They later bought and sold land in Jamaica for a good profit, which helped fund their travels. As her mother got older, they spent more time in the south of Spain. In 1960, they bought a villa in the Costa de Sol.

Jean's mother died on 19 July 1966 on the island of Tenerife. Jean arranged for her mother to be buried in an Anglican cemetery. Jean was very sad after her mother's death and became a recluse for three years. Her father died in July 1967, but it did not affect her as much as her mother's death.

In 1969, Jean returned to public life when she was invited to an air race from England to Australia. She changed her look and attended many events in London. She was happy that no one broke her record for the England-Australia flight. She was reunited with her Percival Gull, which was in a collection, and gave interviews for BBC radio and television.

She visited Australia and New Zealand in early 1970. She met some of her family after they found out she was there. She attended some events, including the opening of a school named after her in Mangere. She became a patron of the New Zealand Airwoman's Association.

In 1977, she was honored at the opening of the Aviation Pioneers Pavilion at Auckland's Museum of Transport and Technology. She then returned to her home in Spain. In 1982, she was bitten by a dog on the island of Majorca. She refused treatment, and the wound became infected. She died alone in a hotel on Majorca and was buried in a simple grave in 1983. Her death was not discovered until September 1987.

Jean Batten's Legacy

Many school houses in New Zealand are named after Jean Batten, including at Macleans College and Westlake Girls High School. A primary school in Mangere is named after her, as are streets in Auckland, Christchurch, Mount Maunganui, Wellington, and Rotorua. The historic Jean Batten building in Auckland is now part of the new Bank of New Zealand head office.

The Auckland Airport International Terminal is also named after her. Her Percival Gull G-ADPR, the plane she used for her record-breaking flights, is displayed in the Jean Batten International Terminal. In 1990, she was added to the New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame for her aviation achievements.

In 1939, a 1,971-meter (6,467 ft) peak in the Ailsa Mountains of Fiordland was named after her.

A bronze statue of Jean Batten is in the main terminal of Rotorua Regional Airport, and memorial panels are also there. A small park in Rotorua city is named after her, and the Jean Batten Memorial is located there.

In September 2009, a Qantas Boeing 737 plane was named after Jean Batten. Also in September 2009, a street in Palma, where Batten died, was renamed Carrer de Jean Batten (Jean Batten St.).

Major Flights and Records

- 8 May to 23 May 1934 – England to Australia: She flew 10,500 miles (16,900 km) in 14 days, 22 hours, and 30 minutes. This set a new solo women's record, beating Amy Johnson's record by over four days.

- 8 April to 29 April 1935 – Australia to England: She flew in 17 days, 16 hours, and 15 minutes. She was the first woman ever to make a return flight.

- 11 November to 13 November 1935 – England to Brazil: She flew 5,000 miles (8,000 km) in 61 hours and 15 minutes, setting a world record for any type of airplane. She also made the fastest crossing of the South Atlantic Ocean (13 hours, 15 minutes) and was the first woman to fly from England to South America.

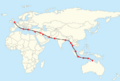

- 5 October to 16 October 1936 – England to New Zealand: She flew 14,224 miles (22,891 km) in 11 days and 45 minutes, including a two-day stop in Sydney. This was a world record for any type of plane.

- 19 October to 24 October 1937 – Australia to England: She flew in 5 days, 18 hours, and 15 minutes. This gave her solo records for both directions at the same time. This was her last long-distance flight.

Images for kids

-

A Britannia Airways Boeing 737, which the airline named "Jean Batten". She was at the naming ceremony in London in 1981.

See also

In Spanish: Jean Batten para niños

In Spanish: Jean Batten para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |