John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Duke of Northumberland

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 1504 London |

| Died | 22 August 1553 (aged 48–49) Tower Hill, London |

| Cause of death | Beheaded |

| Resting place | Chapel Royal of St. Peter ad Vincula, Tower of London |

| Tenure | 1551–1553 |

| Other titles | Viscount Lisle Earl of Warwick |

| Known for | De facto ruling England, 1550–1553 |

| Nationality | English |

| Residence | Ely Place, London Durham House, London Dudley Castle, West Midlands |

| Locality | West Midlands |

| Wars and battles | Italian War of 1521–26 Italian War of 1542–46 • Siege of Boulogne • Battle of the Solent The Rough Wooing • Battle of Pinkie Cleugh Kett's Rebellion Campaign against Mary Tudor, 1553 |

| Offices | Vice-Admiral Lord Admiral Governor of Boulogne Lord Great Chamberlain Grand Master of the Royal Household Lord President of the Council Warden General of the Scottish Marches Earl Marshal of England |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Issue |

|

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (born 1504 – died 22 August 1553) was an important English general, admiral, and politician. He led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 to 1553. After the King's death, he tried to make Lady Jane Grey the Queen of England, but he was not successful.

John Dudley was the son of Edmund Dudley, a minister who worked for King Henry VII. His father was executed by Henry VIII. When John was seven, he became the ward (meaning he was placed under the care of a guardian) of Sir Edward Guildford. John grew up in Guildford's home with his future wife, Jane, who was Guildford's daughter. They had 13 children together.

Dudley served as Vice-Admiral and then Lord Admiral from 1537 to 1547. During this time, he greatly improved how the navy was organized and was a very creative commander at sea. He was also very interested in exploring new lands. Dudley fought in wars in Scotland and France in 1544. He was one of King Henry VIII's closest friends in the King's final years. He also helped lead the religious reform movement at court.

In 1547, Dudley was given the title Earl of Warwick. He fought bravely in the war against Scotland at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh. In 1549, when there were many uprisings across England, Dudley stopped Kett's Rebellion in Norfolk. He believed the Duke of Somerset, who was the Lord Protector, was not doing a good job. So, in October 1549, Dudley and other important advisors removed Somerset from power.

By early 1550, Dudley became the main leader for the 12-year-old King Edward VI. He made peace with Somerset, but Somerset soon started to plot against him. Somerset was later executed based on charges that were mostly made up. Three months before this, in October 1551, Dudley was given the higher title of Dukedom of Northumberland.

As Lord President of the Council, Dudley led a government where many advisors worked together. He tried to involve the young King in government decisions. He took over a government that was almost out of money. He ended the expensive wars with France and Scotland and improved the country's finances, which helped the economy recover. To prevent more uprisings, he set up a system of local policing across the country. He appointed lord-lieutenants who stayed in close contact with the central government. Dudley's religious policies followed King Edward's strong Protestant beliefs. He pushed for the English Reformation and promoted radical reformers to important Church positions.

In early 1553, the 15-year-old King became very sick. He decided to remove his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, from the line of succession. He believed they were not legitimate heirs. As he was dying, Edward changed his will so that his Protestant cousin, Jane Grey, who was Northumberland's daughter-in-law, could become Queen.

It's not fully clear how much Dudley influenced this plan. Some historians believe it was Dudley's idea to keep his power by putting his family on the throne. Others think it was truly Edward's plan, which Dudley then carried out after the King's death. Dudley did not prepare well for this event. He marched to East Anglia to capture Mary, but he surrendered when he heard that the Privy Council had changed their minds and declared Mary Queen.

Dudley was found guilty of treason. Before his execution, he returned to Catholicism and gave up his Protestant faith. He was disliked by both religious groups and became a popular scapegoat, known as the "wicked Duke." Only since the 1970s have historians also seen him as a loyal servant of the House of Tudor. They now see him as a skilled statesman who worked well during difficult times.

Contents

Dudley's Early Life and Career

John Dudley was the oldest of three sons. His father, Edmund Dudley, was an advisor to King Henry VII. His mother was Elizabeth Grey, 6th Baroness Lisle. In 1510, his father was accused of high treason and executed. This happened because the new king, Henry VIII, needed someone to blame for his father's unpopular money policies.

In 1512, when John was seven, he became the ward of Sir Edward Guildford. This meant he lived in Guildford's household. At the same time, his father's treason charge was removed, and John Dudley's family name and rights were restored. The King hoped John Dudley would serve him well in the future.

Around age 15, John Dudley likely went with his guardian to Pale of Calais (an English territory in France) to serve there for several years. He joined important diplomatic trips in 1521 and 1527. He was knighted in 1523 during his first major military experience, an invasion of France. By 1524, Dudley was a "Knight of the Body," a personal attendant to the King. From 1534, he was in charge of the King's body armor as the Master of the Tower Armoury.

He was known for being very skilled in sports, especially wrestling, archery, and royal tournaments. A French report in 1546 called him "the most skilful of his generation, both on foot and on horseback."

In 1525, Dudley married Jane Guildford, who was four years younger than him and had been his classmate. The Dudleys were part of the new Protestant movement in the early 1530s. Their 13 children were educated in Renaissance humanism (a focus on human values and achievements) and science.

In 1534, Sir Edward Guildford died without a will. His only son had died before him. Guildford's nephew claimed he should inherit everything. Dudley and his wife disagreed. They went to court, and Dudley won the case with the help of Thomas Cromwell, a powerful minister.

Dudley was present when Henry VIII met with Francis I of France in Calais in 1532. Anne Boleyn, who would soon be queen, was also there. Dudley attended the christenings of the King's children, Elizabeth and Edward. In 1537, he traveled to Spain to announce Prince Edward's birth to the Emperor. He served as a Member of Parliament for Kent from 1534 to 1536. He also led troops against the Pilgrimage of Grace, a rebellion in late 1536.

In January 1537, Dudley became Vice-Admiral and started focusing on naval matters. He was Master of the Horse (in charge of the royal stables) for Anne of Cleves and Katherine Howard. In 1542, he returned to the House of Commons as an MP for Staffordshire. Soon after, on March 12, 1542, he was promoted to the House of Lords. He became Viscount Lisle after his stepfather died, inheriting the title through his mother. As a peer, Dudley became Lord Admiral and a Knight of the Garter in 1543. He also joined the Privy Council, a group of the King's closest advisors.

After the Battle of Solway Moss in 1542, he served as Warden of the Scottish Marches (border areas). In the 1544 war, an English fleet led by Dudley supported the land army. Dudley helped destroy Edinburgh after breaking down the main gate with a large cannon. In late 1544, he became Governor of Boulogne, a French town that England had captured. His oldest son, Henry, died during the siege of Boulogne. Dudley's job was to rebuild the town's defenses and protect it from French attacks.

As Lord Admiral, Dudley created the Council for Marine Causes. This group was the first to coordinate all the tasks needed to keep the navy running. This made English naval administration the most efficient in Europe. At sea, Dudley's fighting orders were very advanced. He organized ships into squadrons based on their size and firepower. These squadrons would move together in formation and use coordinated gunfire. These were all new ideas for the English navy.

In 1545, he led the fleet's operations during and after the Battle of the Solent. He hosted King Henry on his flagship, the Henri Grace a Dieu. Sadly, the Mary Rose sank during this time, with 500 men on board. In 1546, John Dudley went to France for peace talks. He suspected the French admiral was trying to restart the war. So, Dudley suddenly sailed his fleet out to show English strength, then returned to the negotiating table. He then traveled to Fontainebleau, where the English delegates were entertained by the French King Francis and his son. In the Peace of Camp, the French king recognized Henry VIII's title as "Supreme Head of the Church of England and Ireland." This was a big success for England and its Lord Admiral.

John Dudley was popular and highly respected by King Henry as a general. He became a close friend of the King and played cards with the ailing monarch. Along with Edward Seymour, the King's uncle, Dudley was a leader of the Protestant reform party at court. Both their wives were friends with Anne Askew, a Protestant who was executed in 1546. In September, Dudley hit Bishop Gardiner during a council meeting. This was a serious offense, and he was lucky to only be sent away from court for a month. In the last weeks of Henry VIII's reign, Seymour and Dudley helped the King act against the conservative House of Howard. This cleared the way for a Protestant government to rule during the young King Edward's childhood. People saw them as the likely leaders of the upcoming regency (a period when a country is ruled by someone acting as a regent because the monarch is too young or ill).

From Earl of Warwick to Duke of Northumberland

King Henry VIII's will named 16 executors who would form a council to rule while Edward VI was a child. This new Council agreed to make Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, the Lord Protector with full powers, almost like a king. At the same time, the Council gave themselves promotions, as Henry VIII had wished. The Earl of Hertford became the Duke of Somerset, and John Dudley was made Earl of Warwick. The new Earl had to give his job as Lord Admiral to Somerset's brother, Thomas Seymour. However, Dudley was promoted to Lord Great Chamberlain, a very important position. He was seen as the most important person after the Protector. He was friendly with Somerset, who soon restarted the war with Scotland. Dudley went with him as second-in-command and enjoyed fighting. In one battle, he fought his way out of an ambush and chased a Scottish leader for about 250 meters with a spear. In the Battle of Pinkie, Dudley led the front lines and was key to the English victory.

The Protector's policies about farming and his public announcements were influenced by thinkers who criticized landowners. This made many common people believe that enclosures (fencing off common land) were against the law. As a major landowner himself, Dudley soon worried this would cause big problems. He quietly tried to warn Somerset. By the summer of 1549, there were widespread protests and rebellions across England. The Marquess of Northampton could not restore order near Norwich. So, John Dudley was sent to deal with Kett's Rebellion. Dudley offered the rebel leader, Robert Kett, a pardon if his peasant army would leave immediately. Kett refused. The next night, Dudley stormed the city with a small group of hired soldiers and drove the rebels out after fierce street fighting. He immediately hanged 49 prisoners. Two days later, Kett's main camp outside the city fought the royal army. Over 2,000 peasants were killed. In the following weeks, Dudley held military trials and executed many rebels, perhaps up to 300. The local gentry, who were angry and humiliated, still wanted more punishment. Dudley warned them: "Is there no place for pardon? ... What shall we then do? Shall we hold the plough ourselves, play the carters and labour the ground with our own hands?"

The Lord Protector, Somerset, often appealed to the common people in his announcements. To his colleagues, whom he rarely consulted, he seemed very bossy. By autumn 1549, the same advisors who had made him Protector believed he had failed to rule properly and would not listen to good advice. Dudley still had the troops from the Norfolk campaign. In October 1549, he joined other important advisors to remove the Protector from office. They met in Dudley's home. Both sides accused the other of treason and claimed to be protecting the King. Somerset tried to gather support from the people and hid with the King at Windsor Castle. Using military force near the King was unthinkable. Dudley and Archbishop Cranmer made a deal with Somerset, who then surrendered. To keep up appearances, the 12-year-old King personally ordered his uncle's arrest. For a short time, some people hoped for a return to conservative religious policies. However, Dudley and Cranmer ensured the Protestant reforms continued. They persuaded Edward to appoint more Protestant-minded members to the Council. In December 1549, one advisor tried to accuse Dudley of treason, saying he had been an ally of the Protector. This plan failed when Dudley invited the council to his house. He surprised the plotters by putting his hand on his sword and saying, "my lord, you seek his [Somerset's] blood and he that seeketh his blood would have mine also."

Dudley gained more power through changes in government. By January 1550, he was effectively the new regent. On February 2, 1550, he became Lord President of the Council. This allowed him to remove advisors from the council and appoint new ones. He removed conservative members but arranged for Somerset's release and his return to the Privy Council. In June 1550, Dudley's son John married Somerset's daughter Anne as a sign of peace. However, Somerset soon gathered political supporters and hoped to regain power by getting rid of Dudley. He admitted later that he thought about arresting and executing the Lord President. Somerset used his popularity to campaign against Dudley's policies. His actions threatened the unity needed in a government led by a child king. Dudley would not take any chances. He also wanted to become a duke. He needed to show his power and impress his supporters. Like Somerset, he had to represent the King's honor. He was made Duke of Northumberland on October 11, 1551, with the Duke of Somerset taking part in the ceremony. Five days later, Somerset was arrested. Rumors spread that Somerset had planned a "banquet massacre" to attack the council and kill Dudley. Somerset was found not guilty of treason but guilty of a lesser crime for raising armed men without permission. He was executed on January 22, 1552. While these events were technically legal, they made Northumberland very unpopular. Dudley himself later confessed that "nothing had pressed so injuriously upon his conscience as the fraudulent scheme against the Duke of Somerset."

Leading England

Instead of taking the title of Lord Protector, John Dudley aimed to rule as "first among equals." The government under him was more cooperative and less bossy than under Somerset. The new Lord President of the Council changed some high-ranking jobs. He became Grand Master of the Household himself and gave Somerset's old job of Lord Treasurer to William Paulet, 1st Marquess of Winchester. The Grand Master job meant overseeing the Royal Household, which allowed Dudley to control the King's personal staff and surroundings. He did this through his trusted friends, Sir John Gates and Lord Thomas Darcy. Dudley also placed his son-in-law Sir Henry Sidney and his brother Sir Andrew Dudley close to the King. William Cecil was working for the Duke of Somerset but slowly became loyal to John Dudley. Dudley made him Secretary of State and considered him a very loyal and wise advisor. In this role, Cecil was Dudley's trusted helper. He prepared the Privy Council meetings according to Dudley's wishes. Cecil also had close contact with the King, as Edward worked closely with the secretaries of state.

Dudley organized Edward's political education so that the King would be interested in government matters and at least appear to make decisions. He wanted the King to take over his authority as smoothly as possible. This would reduce conflicts when Edward became an adult ruler. It would also give Dudley a good chance to continue as the main minister. From about age 14, Edward's signature on documents no longer needed the council's approval. The King regularly met with a council of his own choosing, which included the main administrators and the Duke of Northumberland. Dudley had a warm but respectful relationship with the teenager. The Imperial ambassador said Edward "loved and feared" him. At one dinner, Edward talked with the ambassador for a long time until Northumberland quietly signaled to the King that he had said enough. However, the Duke did not always get his way. In 1552–1553, the King's decisions sometimes went against Dudley's wishes. At court, many different people influenced the King, and Edward listened to more than one voice.

Social and Economic Changes

Dudley wanted to make the government more efficient and keep public order to prevent more rebellions like those in 1549. He used a new law "for the punishment of unlawful assemblies." He created a united front of landowners and the Privy Council. The government would step in locally at any sign of trouble. He brought back the old practice of allowing nobles to keep armed followers. He also appointed lord-lieutenants who represented the central government and kept small groups of cavalry ready. These actions worked well, and the country remained calm for the rest of Edward's reign. In fact, in the summer of 1552, a year before the succession crisis, the cavalry groups were disbanded to save money.

John Dudley also tried to improve the lives of ordinary people. The 1547 law that said any unemployed man found wandering could be branded and made a slave was removed in 1550 because it was too harsh. In 1552, Northumberland passed a new Poor Law through parliament. This law arranged for weekly collections in each parish to help the poor. Parishes were supposed to record their needy residents and how much people agreed to donate for them. If people were unwilling to contribute, the local priest and, if needed, the bishop would try to persuade them. The years 1549–1551 had bad harvests, which caused food prices to rise sharply. Dudley tried to stop dishonest middlemen by ordering official searches for hidden grain and by setting maximum prices for food. However, the prices were so low that farmers stopped selling their produce in the open market, and the rules had to be canceled. The government's farming policy gave landowners a lot of freedom to enclose common land. But it also started to prosecute landowners who made illegal enclosures.

The previous government had left huge debts and a currency that had been made much less valuable (debased). On his second day as Lord President of the Council, Dudley began to fix the problems with the mint (where coins are made). He set up a committee to investigate dishonest practices by mint officers. In 1551, the government tried to make money and restore trust in the currency by issuing even more debased coins and then immediately reducing their value. This caused panic and confusion. To fix the situation, a coin with 92.3% silver content (compared to 25% in the last debasement) was issued within months. However, the bad coins were still preferred because people had lost trust. Northumberland admitted defeat and hired a financial expert, Thomas Gresham. After the first good harvest in four years, by late 1552, the currency was stable, food prices had dropped, and the economy was ready to recover. A process to centralize how the Crown's money was managed was underway, and foreign debt had been paid off.

Religious Changes

The use of the Book of Common Prayer became law in 1549. King Edward's half-sister, Mary Tudor, was allowed to continue attending mass privately. As soon as he was in power, Dudley pressured her to stop her entire household and many visitors from attending mass. Mary, who did not allow the Book of Common Prayer in any of her homes, refused to compromise. She planned to flee the country but changed her mind at the last minute. Mary blamed John Dudley entirely for her problems, denying that Edward had any personal interest in the issue. After a meeting with the King and Council, where she was told that her disobedience to the law was the problem, not her faith, she sent the Imperial ambassador to threaten war on England. The English government could not accept a war threat from an ambassador who had overstepped his authority. But they also did not want to risk important trade with the Habsburg Netherlands. So, an embassy was sent to Brussels, and some of Mary's household officers were arrested. On his next visit to the council, the ambassador was told by the Earl of Warwick that the King of England had as much authority at 14 as he would at 40. Dudley was referring to Mary's refusal to accept Edward's demands because of his young age. In the end, a quiet agreement was reached: Mary continued to attend mass more privately, while also gaining more land from the Crown.

John Dudley became the main supporter of Protestant clergy, promoting several to important Church positions, such as John Hooper and John Ponet. The English Reformation continued quickly, even though it was not very popular. The 1552 revised Book of Common Prayer rejected the idea of transubstantiation (the belief that bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ). The Forty-two Articles, issued in June 1553, stated that salvation comes through faith alone and denied the existence of purgatory. Even though these were important projects for Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, he was unhappy with how the government handled them. By 1552, the relationship between the Archbishop and the Duke was very cold. To prevent the Church from becoming independent of the state, Dudley was against Cranmer's plan to reform canon law (Church law). He even recruited the Scottish reformer John Knox to "sharpen the Bishop of Canterbury," as Northumberland put it. Knox refused to cooperate but joined other reformers in speaking out against greedy people in high places. Cranmer's canon law reforms were finally stopped by Northumberland's angry intervention in the spring parliament of 1553. On a personal level, however, the Duke was happy to help create a cathechism (a book of religious instruction) for schoolchildren in Latin and English. In June 1553, he supported the Privy Council's invitation for Philip Melanchthon, a famous German reformer, to become a professor at Cambridge University. If the King had not died, Melanchthon would have come to England.

A major problem between Northumberland and the Church leaders was the Church's wealth. The government and its officials had profited from taking Church property ever since the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The most radical preachers believed that bishops, if needed at all, should not have noble titles or wealth. This idea appealed to Dudley because it allowed him to fill the royal treasury or give rewards using Church property. When new bishops were appointed, they often had to give up large amounts of land to the Crown and were left with much less income. The Crown's financial problems led the Council to take even more Church property in 1552–1553, targeting lands and silver items from churches. At the time, and since, the breaking up and reorganization of the Prince-Bishopric of Durham was seen as Dudley's attempt to create his own special territory. However, all the money from Durham was given to the two new bishoprics and the nearby border army post. Dudley received the management of the new "King's County Palatine" in the North (worth £50 a year), but he gained no further personal wealth from it. Overall, Northumberland's plans for reorganized dioceses (Church districts) show he wanted to ensure that "the preaching of the gospel" had enough money. Still, taking Church property and the government's control over Church affairs made the Duke disliked by clergy, both Protestant and conservative. His relations with them were at their worst when King Edward's final illness began.

Peace and Overseas Interests

The war policy from 1547–1549 had cost about £350,000 a year, while the Crown's regular income was only £150,000 a year. This could not continue. Dudley quickly negotiated the withdrawal of the English soldiers from Boulogne, which was under siege. This saved the high costs of the soldiers, and the French payments of about £180,000 were a very welcome cash income. Peace with France was made in the Treaty of Boulogne in March 1550. There was both public celebration and anger at the time. Some historians have called this peace a shameful surrender of English territory. A year later, it was agreed that King Edward would marry a French princess, the six-year-old Elisabeth of Valois. The threat of war with Scotland was also removed. England gave up some isolated military posts in exchange. In the peace treaty with Scotland in June 1551, a joint group, one of the first of its kind, was set up to agree on the exact border between the two countries. This was settled in August 1552 with French help. Even though fighting stopped, English defenses remained strong. Nearly £200,000 a year was spent on the navy and the military posts at Calais and on the Scottish border. As Warden-General of the Scottish Marches, Northumberland arranged for a new Italian-style fortress to be built at Berwick-upon-Tweed.

The war between France and the Emperor started again in September 1551. Northumberland refused requests for English help from both sides. He pursued a policy of neutrality, trying to balance relations between the two great powers. In late 1552, he tried to bring about peace in Europe through English mediation. These efforts were taken seriously by the ambassadors, but the warring countries ended them in June 1553, as continuing the war was more beneficial to them.

John Dudley got back the job of Lord Admiral immediately after the Protector's fall in October 1549. He had given the job to Edward Lord Clinton in May 1550, but he never lost his strong interest in sea matters. Henry VIII had greatly changed the English navy, mainly for military purposes. Dudley encouraged English ships to sail to distant coasts, ignoring Spanish threats. He even thought about raiding Peru with Sebastian Cabot in 1551. Expeditions to Morocco and the Guinea coast in 1551 and 1552 actually happened. A planned voyage to China through the Northeast Passage under Hugh Willoughby sailed in May 1553. King Edward watched them leave from his window. Northumberland was at the center of a "maritime revolution," a policy where the English Crown directly supported long-distance trade more and more.

The Year 1553: Changing the Succession

The 15-year-old King Edward VI became very ill in February 1553. His sister Mary was invited to visit him, and the Council treated her "as if she had been Queen of England." The King got a little better, and in April, Northumberland restored Mary's full title and rights as Princess of England, which she had lost in the 1530s. He also kept her informed about Edward's health. Around this time, some long marriage negotiations were finished. On May 21, 1553, Guildford Dudley, Northumberland's second youngest son, married Lady Jane Grey. She was the very Protestant daughter of the Duke of Suffolk and a grandniece of Henry VIII through her mother. Her sister Catherine was married to the heir of the Earl of Pembroke. Another Katherine, Guildford's younger sister, was promised to Henry Hastings, heir of the Earl of Huntingdon. Within a month, the first of these marriages became very important. Although they were celebrated with grand parties, at the time, these marriages were not seen as politically important, not even by the Imperial ambassador, who was usually very suspicious. Often seen as proof of a plot to put the Dudley family on the throne, they have also been described as normal marriages between noble families.

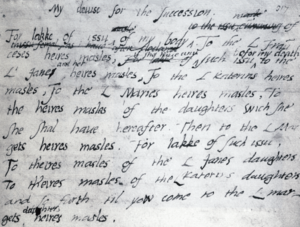

At some point during his illness, Edward wrote a document titled "My devise for the Succession." Because he was a strong Protestant, Edward did not want his Catholic sister Mary to become queen. He was also concerned about male succession and legitimacy, which was questionable for Mary and Elizabeth due to Henry VIII's laws. In the first version of his "devise," written before he knew he was dying, Edward skipped his half-sisters and planned for only male heirs to succeed. Around late May or early June, Edward's condition worsened greatly. He changed his draft so that Lady Jane Grey herself, not just her possible sons, could inherit the Crown. It is unclear how much Edward's document—especially this last change—was influenced by Northumberland, his trusted friend John Gates, or other members of the Privy Chamber like Edward's tutor John Cheke or Secretary William Petre.

Edward fully supported the plan. He personally oversaw the copying of his will and twice called lawyers to his bedside to give them instructions. On the second occasion, June 15, Northumberland watched closely. Days before, the Duke had intimidated the judges who had legal objections to the "devise." The next step was a promise to carry out the King's will after his death. This was signed in Edward's presence by Northumberland and 23 others. Finally, the King's official "declaration," issued as letters patent, was signed by 102 important people, including the entire Privy Council, nobles, bishops, judges, and London officials. Edward also announced that it would be passed in parliament in September, and the necessary legal documents were prepared.

It was now widely known that Edward was dying. The Imperial ambassador had been convinced for years that Dudley was involved in some "mighty plot" to put his own family on the throne. However, as late as June 12, he still knew nothing specific, even though he had inside information about Edward's sickness. France, which did not want the Emperor's cousin on the English throne, hinted at supporting Northumberland. Since the Duke did not rule out an armed attack from Charles V, he accepted the French offer after the King's death. He sent a secret mission to King Henry II without making any firm promises. After Jane became queen in July, the ambassadors of both France and the Emperor believed she would succeed, although they knew that ordinary people supported Mary. The French ambassador wrote about Guildford Dudley as "the new King." The Emperor told his envoys to work with the Duke and to discourage Mary from doing anything dangerous.

Whether changing the succession was Edward's own idea or not, he was determined to exclude his half-sisters. He wanted to protect what he saw as his threatened legacy. The original parts of the "devise" have been called strange and obsessive, typical of a teenager, but not fitting for a practical politician. Mary becoming queen could cost Northumberland his life, but not necessarily. He tried hard to please her in 1553 and may have thought she would become queen as late as early June. Faced with Edward's clear royal will and determination, John Dudley followed his master's wishes. He either saw a chance to keep his power after the King's death or acted out of loyalty.

Dudley's Downfall

King Edward VI died on July 6, 1553. The next morning, Northumberland sent his son Robert with 300 men to capture Mary Tudor in Hertfordshire. Knowing about her half-brother's condition, Mary had moved to East Anglia just days before, where she owned the most land. She began to gather armed followers and sent a letter to the council, demanding to be recognized as queen. It arrived on July 10, the day Jane Grey was proclaimed queen. The Duke of Northumberland's speech to Jane the day before did not convince her to accept the Crown; her parents' help was needed for that. Dudley had not prepared for Mary's strong actions and needed a week to build a larger army. He faced a problem: who should lead the troops? He was the most experienced general in the kingdom, but he did not want to leave the government in the hands of his colleagues, some of whom he did not trust much. Queen Jane decided the issue by demanding that her father, the Duke of Suffolk, stay with her and the council. On July 14, Northumberland headed for Cambridge with 1,500 troops and some artillery. He reminded his colleagues of the seriousness of their cause, saying, "whatever chance of disagreement might grow amongst you in my absence."

Mary's military camp in East Anglia was growing stronger every day, supported by local nobles and landowners. By chance, she also got powerful artillery from the royal navy. Given the situation, the Duke thought fighting was hopeless. His army moved from Cambridge to Bury St Edmunds and then retreated back to Cambridge. On July 20, a letter arrived from the Council in London. It declared that they had proclaimed Mary Queen and ordered Northumberland to disband his army and wait. Dudley did not resist. He explained to his fellow commanders that they had always acted on the council's orders. He said he did not want "to combat the Council's decisions, supposing that they have been moved by good reasons ... and I beg your lordships to do the same." He proclaimed Mary Tudor queen in the market square, threw his cap in the air, and "so laughed that the tears ran down his cheeks for grief." The next morning, the Earl of Arundel arrived to arrest him. A week earlier, Arundel had told Northumberland he would gladly spill his blood for him. Now, Dudley knelt as soon as he saw Arundel.

Northumberland rode through the City of London to the Tower on July 25. His guards struggled to protect him from the angry crowd. A pamphlet published shortly after his arrest showed the general hatred for him: "the great devil Dudley ruleth, Duke I should have said." People commonly believed he had poisoned King Edward, while Mary "would have been as glad of her brother's life, as the ragged bear is glad of his death." The French ambassador was shocked by how quickly things changed. He wrote, "I have witnessed the most sudden change believable in men, and I believe that God alone worked it."

Trial and Execution

Northumberland was tried on August 18, 1553, in Westminster Hall. The jury and judges were mostly his former colleagues. Dudley suggested that he had acted under the authority of the King and Council and with the official Great Seal. He was told that the Great Seal of a usurper (someone who takes power illegally) was worth nothing. He then asked "whether any such persons as were equally culpable of that crime ... might be his judges." After he was sentenced, he begged the Queen for mercy for his five sons. His oldest son was condemned with him, and the others were waiting for their trials. He also asked to "confess to a learned divine" (a religious scholar). Bishop Stephen Gardiner, who had spent most of Edward's reign in the Tower and was now Mary's Lord Chancellor, visited him. Dudley's execution was planned for August 21 at eight in the morning. However, it was suddenly canceled. Instead, Northumberland was taken to St Peter ad Vincula, where he took Catholic communion. He stated that "the plagues that is upon the realm and upon us now is that we have erred from the faith these sixteen years." This was a big propaganda victory for the new government. Dudley's words were officially shared, especially in the lands of the Emperor Charles V. In the evening, the Duke learned "that I must prepare myself against tomorrow to receive my deadly stroke," as he wrote in a desperate plea to the Earl of Arundel: "O my good lord remember how sweet life is, and how bitter ye contrary."

How History Remembers John Dudley

Historical Reputation

A negative story about the Duke of Northumberland began even while he was still in power, and it grew stronger after his fall. People claimed that from the last days of Henry VIII, he had planned for years to destroy both of King Edward's Seymour uncles (Lord Thomas and the Protector) as well as Edward himself. He also served as a convenient scapegoat. It was easiest for Queen Mary to believe that Dudley had acted alone, and no one had a reason to doubt it. Further questions were not welcome, as the Emperor Charles V's ambassadors found out: "it was thought best not to inquire too closely into what had happened, so as to make no discoveries that might prejudice those [who tried the duke]." By giving up the Protestant faith he had so clearly supported, Northumberland lost all respect. He could not be seen in a good light in a world where people thought in terms of religious groups. Protestant writers focused on the achievements of the religious King Edward and made Somerset into the "good Duke." This meant there had to be a "wicked Duke" too. This idea was strengthened by later historians who saw Somerset as a hero of freedom whose desire "to do good" was stopped by, as one historian put it, "the subtlest intriguer in English History."

Even as late as 1968/1970, one historian used this good duke/bad duke idea in a study of Edward VI's reign. However, he believed the King was about to take full power in early 1553 (with Dudley thinking about retiring). He thought the change in succession was Edward's decision, and Northumberland played the part of a loyal and tragic enforcer, rather than the original planner. Many historians since then have seen the "devise" as Edward's own project. Others, while noting how poorly the plan was carried out, still believe Northumberland was behind the scheme, but that he agreed with Edward's beliefs. They suggest the Duke acted out of desperation to survive, or to save political and religious reforms and protect England from being controlled by the Habsburg family.

Since the 1970s, new studies of the Duke of Somerset's policies and leadership style have led to the recognition that Northumberland improved and reformed the Privy Council as a key part of the government. Historians now say he "took the necessary but unpopular steps to hold the minority regime together." Stability and rebuilding are seen as the main features of most of his policies. His motivations range from "determined ambition" to "idealism of a sort." One historian concluded in 1980: "given the circumstances which he inherited in 1549, the duke of Northumberland appears to have been one of the most remarkably able governors of any European state during the sixteenth century."

Personality

John Dudley's decision to give up his Protestant faith before his execution pleased Queen Mary and angered Lady Jane. Most people, especially Protestants, thought he was trying to get a pardon by doing this. Historians have often believed he had no real faith and was just a cynic. Other explanations, both from his time and now, suggest that Northumberland tried to save his family from execution. Or that, facing disaster, he found comfort in the Church of his childhood. Or that he saw God's will in Mary's success. Although he supported the Reformation from at least the mid-1530s, Dudley may not have understood complex religious ideas, being a "simple man in such matters." The Duke was upset by a very direct letter he received from John Knox, whom he had invited to preach before the King and had unsuccessfully offered a bishopric.

Northumberland was not like the old-style nobles, despite his noble family and life as a great lord. He bought, sold, and traded lands, but he never tried to build a large power base of land or a big armed force of followers (which ended up being a fatal mistake). His highest income from land was £4,300 a year, plus £2,000 a year from other payments. This was suitable for his rank but much less than the £5,333 a year the Duke of Somerset had given himself, reaching an income of over £10,000 a year while in office. John Dudley was a typical servant of the Tudor Crown. He was self-interested but completely loyal to the current ruler. The monarch's every wish was law to him. This unquestioning loyalty may have played a key role in Northumberland's decision to carry out Edward's succession plan, just as it did in his attitude towards Mary when she became queen. Dudley constantly feared that his service might not be good enough or might not be recognized by the monarch. He was also very sensitive about what he called "estimation," meaning his status. His father, Edmund Dudley, was not forgotten. Nine months before his own death, the Duke wrote to Cecil: "my poor father's fate who, after his master was gone, suffered death for doing his master's commandments."

John Dudley was an impressive person with a strong personality. He could also charm people with his politeness and graceful presence. He was a family man, an understanding father and husband who was passionately loved by his wife. He often had periods of illness, partly due to a stomach problem. These caused long absences from court but did not reduce the large amount of paperwork he handled. They may also have included some hypochondria (imagining illnesses). The English diplomat Richard Morrison wrote about his former boss: "This Earl had such a head that he seldom went about anything but he had three or four purposes beforehand." A French observer in 1553 described him as "an intelligent man who could explain his ideas and who displayed an impressive dignity. Others, who did not know him, would have considered him worthy of a kingdom."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: John Dudley para niños

In Spanish: John Dudley para niños