Manuel I Komnenos facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Manuel I Komnenos |

|

|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |

Manuscript miniature of Manuel I (part of double portrait with Maria of Antioch, Vatican Library, Rome)

|

|

| Byzantine emperor | |

| Reign | 8 April 1143 – 24 September 1180 |

| Predecessor | John II Komnenos |

| Successor | Alexios II Komnenos |

| Born | 28 November 1118 |

| Died | 24 September 1180 (aged 61) |

| Spouse | Bertha of Sulzbach Maria of Antioch |

| Issue | Maria Komnene Alexios II Komnenos |

| House | Komnenian dynasty |

| Father | John II Komnenos |

| Mother | Irene of Hungary |

| Religion | Greek Orthodox |

Manuel I Komnenos (born November 28, 1118 – died September 24, 1180) was a powerful Byzantine emperor in the 12th century. He was also called Porphyrogennetos, which means "born in the purple". This title was given to children born to a reigning emperor in a special room of the palace.

Manuel's time as emperor was a very important period for the Byzantine Empire. Under his rule, the empire became strong again, both in its military and its economy. It also saw a rebirth of its culture. Manuel wanted to make his empire as powerful as the old Roman Empire. He worked hard to achieve this goal.

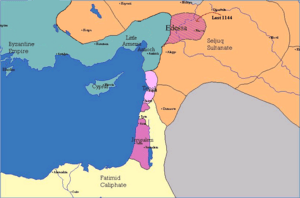

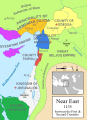

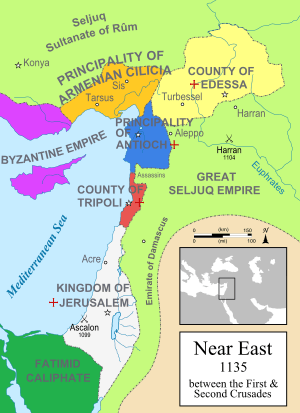

He made alliances with leaders in Western Europe, like Pope Adrian IV. He even tried to take back land in Italy from the Normans, but he wasn't successful. Manuel also cleverly managed the Second Crusade as it passed through his lands. He made the Crusader states in the Middle East, like Antioch, agree to be protected by the Byzantine Empire.

Manuel also fought against Muslim armies in the Holy Land. He joined forces with the Kingdom of Jerusalem to invade Fatimid Egypt. He changed the political map of the Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean. He made countries like Hungary and the Crusader states accept Byzantine leadership. He also fought aggressively against his neighbors in both the west and the east.

However, near the end of his rule, Manuel suffered a big defeat at the Battle of Myriokephalon. This loss happened because he was too confident when attacking a strong Seljuk position. Even though the Byzantines recovered later, Myriokephalon was the last major attempt to take back central Anatolia from the Turks.

The Greeks called Manuel ho Megas, meaning "the Great". People who served him were very loyal. He was also seen as a great emperor in parts of the Western world. Some historians today believe that his power came more from his family, the Komnenian dynasty, than from his own actions. They also point out that the Byzantine Empire declined quickly after his death.

Contents

- Becoming Emperor: Manuel's Rise to Power

- The Second Crusade and Antioch

- Campaigns in Italy

- Protecting the Balkan Borders

- Relations with Kievan Rus' (Russia)

- Invading Egypt

- Kilij Arslan II and the Seljuk Turks

- Manuel's Chivalric Side

- Manuel's Family

- Manuel's Impact and Legacy

- Images for kids

- See also

Becoming Emperor: Manuel's Rise to Power

Manuel Komnenos was born on November 28, 1118. He was the fourth son of John II Komnenos and Irene of Hungary. Because he had older brothers, it seemed unlikely he would become emperor. His grandfather was Saint Ladislaus.

Manuel impressed his father with his bravery during a siege against the Danishmendid Turks in 1140. In 1143, his father, John II, was dying from a wound. On his deathbed, John chose Manuel to be his successor. He picked Manuel over his older brother, Isaac. John said Manuel was brave and willing to listen to advice, unlike Isaac, who was proud and stubborn.

After John II died on April 8, 1143, the army declared Manuel emperor. But his position was not yet secure. His father's army was far away in Cilicia, so Manuel knew he had to return to the capital, Constantinople, quickly. He also had to arrange his father's funeral and build a monastery where his father died.

Manuel quickly sent his trusted general, John Axouch, ahead of him. Axouch's orders were to arrest Isaac, Manuel's most dangerous rival. Isaac was living in the Great Palace and had access to the imperial treasury. Axouch reached Constantinople before news of the emperor's death. He quickly secured the city's loyalty.

When Manuel arrived in Constantinople in August 1143, the new patriarch, Michael II Kourkouas, crowned him. A few days later, with his position secure, Manuel released Isaac. He then gave two gold coins to every household in Constantinople. He also gave 200 pounds of gold to the Byzantine Church.

The empire Manuel inherited was more stable than it had been a century earlier. His grandfather and father had worked hard to fix the problems the empire faced. However, big challenges remained. The Normans in Sicily had taken Italy from Byzantine control. The Seljuk Turks had taken central Anatolia. And new Crusader states in the Levant created new problems for the empire. The emperor's job was very difficult.

The Second Crusade and Antioch

Dealing with Antioch's Prince

Manuel's first big challenge came in 1144. Raymond, the ruler of Antioch, demanded that Manuel give him land in Cilicia. However, later that year, the Crusader state of County of Edessa was attacked by Imad ad-Din Zengi, a powerful Muslim leader.

Raymond realized he couldn't get help from Western Europe. With this new threat, he had no choice but to visit Manuel in Constantinople. He humbled himself and asked for protection. Manuel promised him support, and Raymond agreed to be loyal to the Byzantine Empire.

Campaign Against Konya

In 1146, Manuel gathered his army at Lopadion. He launched an attack against Mas'ud, the Sultan of Rûm. Mas'ud had been constantly attacking the empire's borders in western Anatolia and Cilicia.

Manuel's goal was not to conquer land. Instead, he wanted to punish the Turks. His army defeated the Turks at Acroënus. They then captured and destroyed the town of Philomelion, moving its Christian people to safety. The Byzantine forces reached Mas'ud's capital, Konya, and damaged the area around it. However, they could not break through the city's walls. Manuel also wanted to show Western leaders that he was actively fighting for the Christian cause.

While on this campaign, Manuel received a letter from Louis VII of France. Louis announced that he planned to lead an army to help the Crusader states.

Crusaders Arrive in Constantinople

Events in the Balkans forced Manuel to stop his campaign against the Turks. In 1147, he allowed two armies of the Second Crusade to pass through his lands. These armies were led by Conrad III of Germany and Louis VII of France. Many Byzantines remembered the First Crusade and feared the new one.

The Crusaders often damaged property and stole things as they marched. Byzantine troops followed them to keep order. More troops were gathered in Constantinople to protect the capital. Manuel also repaired the city walls. He made the two kings promise to respect his territory.

Conrad's army entered Byzantine land first in the summer of 1147. Byzantine records suggest they caused more trouble. The historian Kinnamos describes a battle between a Byzantine force and part of Conrad's army outside Constantinople. The Byzantines won, and Conrad agreed to have his army quickly moved across the Bosphorus to Asia.

After 1147, Manuel and Conrad became friends. By 1148, Manuel saw the benefit of an alliance with Conrad. Manuel had married Conrad's sister-in-law, Bertha of Sulzbach, earlier. He convinced Conrad to renew their alliance against Roger II of Sicily. Sadly for Manuel, Conrad died in 1152. Manuel tried many times to make an agreement with Conrad's successor, Frederick Barbarossa, but he failed.

Cyprus is Attacked

Manuel's attention turned to Antioch again in 1156. Raynald of Châtillon, the new Prince of Antioch, claimed Manuel had not paid him money he promised. Raynald then attacked the Byzantine province of Cyprus. He arrested the island's governor, John Komnenos, who was Manuel's nephew.

The historian William of Tyre criticized Raynald's actions against fellow Christians. He described the terrible things Raynald's men did. Manuel responded quickly and strongly. In the winter of 1158–59, he marched to Cilicia with a huge army. He moved so fast that he surprised Thoros of Cilicia, who had helped attack Cyprus. Thoros fled, and Cilicia quickly fell to Manuel.

Manuel's Power in Antioch

News of the Byzantine army's advance reached Antioch. Raynald knew he couldn't defeat the emperor. He also knew he couldn't get help from King Baldwin III of Jerusalem. Baldwin did not approve of Raynald's attack on Cyprus and had already made a deal with Manuel.

Alone and without allies, Raynald decided his only hope was to surrender completely. He appeared dressed in a sack with a rope around his neck, begging for forgiveness. Manuel ignored him at first, talking with his officials. William of Tyre said this humiliating scene lasted so long that everyone present was "disgusted."

Finally, Manuel forgave Raynald. But Raynald had to become a vassal of the Empire. This meant Antioch lost its independence and became part of the Byzantine sphere of influence.

With peace restored, a grand parade was held on April 12, 1159. The Byzantine army entered Antioch triumphantly. Manuel rode through the streets on horseback, while the Prince of Antioch and the King of Jerusalem followed on foot. Manuel gave justice to the people and held games and tournaments.

In May, Manuel led a united Christian army towards Edessa. But he stopped the campaign when Nur ad-Din, the ruler of Syria, released 6,000 Christian prisoners. Even though the expedition ended gloriously, some modern scholars believe Manuel didn't achieve as much as he wanted in restoring the empire.

On their way back to Constantinople, Manuel's troops were surprised by Turks. Despite this, they won a complete victory, defeating the enemy and causing heavy losses. The next year, Manuel drove the Turks out of Isauria.

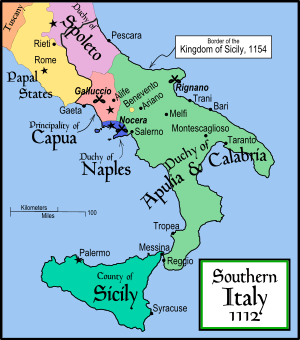

Campaigns in Italy

War with Roger II of Sicily

In 1147, Manuel faced war with Roger II of Sicily. Roger's fleet captured the Byzantine island of Corfu and looted Thebes and Corinth. Manuel was busy with an attack in the Balkans, but in 1148, he allied with Conrad III of Germany. He also got help from the Venetians, whose strong fleet quickly defeated Roger.

In 1149, Manuel took back Corfu. He then prepared to attack the Normans. Roger II sent a fleet of 40 ships to attack Constantinople's suburbs. Manuel had already agreed with Conrad to invade and divide southern Italy and Sicily. This alliance with Germany was a main part of Manuel's foreign policy for the rest of his reign.

Roger died in February 1154. His son, William I, took over. William faced many rebellions in Sicily and Apulia. Many Apulian refugees came to the Byzantine court. Conrad's successor, Frederick Barbarossa, also launched a campaign against the Normans, but it stalled.

These events encouraged Manuel to take advantage of the problems in Italy. In 1155, he sent generals Michael Palaiologos and John Doukas with Byzantine troops, ships, and gold to invade Apulia. They were told to get Frederick's support, but he refused. Frederick's army wanted to return home.

However, with help from local lords who disliked William I, Manuel's expedition made fast progress. All of southern Italy rebelled against the Sicilian king. Many strongholds were captured by force or by offering gold.

Alliance with the Pope

The city of Bari, which had been a Byzantine capital for centuries, opened its gates to Manuel's army. The happy citizens tore down the Norman fortress. After Bari fell, cities like Trani, Giovinazzo, Andria, Taranto and Brindisi were also captured. William arrived with his army, but he was heavily defeated.

Manuel was encouraged by this success. He dreamed of restoring the Roman Empire. He also hoped to unite the Orthodox and Catholic Church. This was a good time for such a union. The Papacy (the Pope's office) usually had problems with the Normans. Having the Byzantines as neighbors was much better for the Pope than dealing with the troublesome Normans.

Pope Adrian IV wanted to make a deal. It would greatly increase his influence over all Christians. Manuel offered the Pope a lot of money for troops. He asked the Pope to give him control of three coastal cities in return for helping to expel William from Sicily. Manuel also promised to pay 5,000 pounds of gold to the Pope. Negotiations happened quickly, and Manuel and Hadrian formed an alliance.

At this point, when the war seemed won, things turned against Manuel. The Byzantine commander Michael Palaiologos upset his allies, slowing the campaign. He was soon called back to Constantinople, which was a big loss. The turning point was the Battle of Brindisi. The Normans launched a major counter-attack by land and sea.

When the enemy approached, the mercenaries hired by Manuel demanded huge pay increases. When refused, they deserted. Even the local lords left, leaving John Doukas outnumbered. The arrival of Alexios Komnenos Bryennios with some ships didn't help. The naval battle was won by the Normans. John Doukas and Alexios Bryennios were captured.

Manuel then sent Alexios Axouch to Ancona to raise another army. But by then, William had already retaken all the Byzantine conquests in Apulia. The defeat at Brindisi ended the Byzantine presence in Italy. In 1158, the Byzantine army left Italy and never returned.

Historians Nicetas Choniates and Kinnamos agree that the peace terms Axouch secured allowed Manuel to leave the war with dignity. This was despite a devastating Norman raid on Euboea and Almira in 1156.

Church Union Fails

During and after the Italian campaign, Manuel tried to convince the popes to unite the Eastern and Western churches. In 1155, Pope Adrian IV wanted to unite the churches. However, hopes for a lasting alliance failed.

Adrian IV and later popes demanded that their religious authority be recognized over all Christians. They wanted to be superior to the Byzantine emperor. Manuel, on the other hand, wanted official recognition of his power over both East and West. Neither side would accept these conditions. Even if Manuel, who was friendly to the West, had agreed, the Greek people of the empire would have rejected it.

Despite his friendly relations with the Roman Church and the popes, Manuel was never given the title of augustus by the popes. He sent envoys to Pope Alexander III twice, offering to reunite the churches. But Alexander refused, saying it would cause too many problems.

The Italian campaign brought limited benefits to the Empire. The city of Ancona became a Byzantine base in Italy. The Normans of Sicily were weakened and made peace with the Empire. This peace lasted for the rest of Manuel's reign. The Empire showed it could get involved in Italian affairs.

However, the huge amount of gold spent on the project (over 2.16 million hyperpyra) showed the limits of what money and diplomacy alone could achieve.

Byzantine Policy in Italy After 1158

After 1158, Byzantine policy changed. Manuel decided to oppose the Hohenstaufen dynasty's goal of taking over Italy. When war started between Frederick Barbarossa and the northern Italian communes, Manuel actively supported the Lombard League. He gave them money, agents, and sometimes troops. The walls of Milan, which the Germans had destroyed, were rebuilt with Manuel's help.

Ancona remained an important center of Byzantine influence in Italy. The people of Ancona willingly submitted to Manuel, and Byzantium kept representatives in the city. Frederick's defeat at the Battle of Legnano on May 29, 1176, seemed to improve Manuel's position in Italy.

According to Kinnamos, cities like Cremona, Pavia, and others joined Manuel. He also had good relations with Genoa and Pisa, but not with Venice. In March 1171, Manuel suddenly broke with Venice. He ordered all 20,000 Venetians in his territory to be arrested and their property taken. Venice was angry and sent a fleet of 120 ships against Byzantium. Due to disease, and being chased by 150 Byzantine ships, the Venetian fleet had to return without much success. Friendly relations between Byzantium and Venice were likely not restored during Manuel's lifetime.

Protecting the Balkan Borders

Manuel worked hard to keep the lands in the Balkans that Basil II had conquered over a hundred years earlier. Problems on his northern border kept Manuel from his main goal of defeating the Normans of Sicily. Relations with the Serbs and Hungarians had been good since 1129, so a Serb rebellion came as a surprise. The Serbs of Rascia, encouraged by Roger II of Sicily, invaded Byzantine territory in 1149.

Manuel forced the rebellious Serbs and their leader, Uroš II, to become his vassals (1150–1152). He then repeatedly attacked the Hungarians to take their land along the Sava River. In wars from 1151–1153 and 1163–1168, Manuel led his troops into Hungary. A spectacular raid deep into enemy land brought back a lot of war treasures.

In 1167, Manuel sent 15,000 men under Andronikos Kontostephanos against the Hungarians. They won a decisive victory at the Battle of Sirmium. This allowed the Empire to make a very good peace treaty with the Kingdom of Hungary. Syrmia, Bosnia, and Dalmatia were given to the Empire. By 1168, almost the entire eastern Adriatic coast was under Manuel's control.

Manuel also tried to unite Hungary with the Empire through diplomacy. The Hungarian heir, Béla, who was the younger brother of King Stephen III, was sent to Constantinople. He was educated at the emperor's court. Manuel planned for Béla to marry his daughter, Maria, and become his heir. This would unite Hungary with the Empire. At court, Béla took the name Alexius and received the title of despot, a high title usually only for the emperor.

However, two unexpected family events changed everything. In 1169, Manuel's young wife gave birth to a son. This meant Béla was no longer the heir to the Byzantine throne. Then, in 1172, Stephen died without children, and Béla went home to become king. Before leaving Constantinople, he promised Manuel that he would always "keep in mind the interests of the emperor and of the Romans." Béla III kept his word. As long as Manuel lived, he did not try to take back the Croatian lands that Manuel had taken from Hungary. He only did so after Manuel's death.

Relations with Kievan Rus' (Russia)

Manuel Komnenos tried to get the Russian princes to join his diplomatic efforts against Hungary and Sicily. This divided the Russian princes into groups that were either pro-Byzantine or anti-Byzantine. In the late 1140s, three princes were fighting for power in Russia. Prince Iziaslav II of Kiev was related to Géza II of Hungary and was against Byzantium. Prince Yuri Dolgoruki of Suzdal was Manuel's ally. Vladimirko of Galicia was described as Manuel's vassal. Galicia was important because it was on Hungary's northern border, which was key in the Byzantine-Hungarian conflicts.

After Iziaslav and Vladimirko died, the situation changed. Yuri of Suzdal, Manuel's ally, took over Kiev. But Yaroslav, the new ruler of Galicia, became pro-Hungarian.

In 1164–65, Manuel's cousin Andronikos, who would later become emperor, escaped from Byzantine captivity. He fled to Yaroslav's court in Galicia. This was alarming because Andronikos might try to take Manuel's throne with support from Galicia and Hungary. This made the Byzantines act quickly. Manuel forgave Andronikos and convinced him to return to Constantinople in 1165.

A mission to Kiev, then ruled by Prince Rostislav, resulted in a good treaty. Rostislav promised to send troops to help the Empire. Yaroslav of Galicia was also convinced to end his ties with Hungary and fully rejoin the imperial side. Even as late as 1200, the princes of Galicia were helping the Empire against its enemies, the Cumans.

The improved relations with Galicia helped Manuel immediately. In 1166, he sent two armies to attack the eastern parts of Hungary. One army crossed the Walachian Plain and entered Hungary through the Transylvanian Alps. The other army went a long way around to Galicia. With Galician help, it crossed the Carpathian Mountains. Most Hungarian forces were on the Sirmium and Belgrade border, so they were surprised by the Byzantine invasion. This led to the Hungarian province of Transylvania being severely damaged by the Byzantine armies.

Invading Egypt

Alliance with Jerusalem

Controlling Egypt had been a long-held dream for the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Its king, Amalric I, needed all the military and financial help he could get for his planned campaign. Amalric also realized that if he wanted to conquer Egypt, he might have to let Manuel have more influence over Antioch. Manuel had paid 100,000 dinars to release Bohemond III.

In 1165, Amalric sent envoys to the Byzantine court to arrange a marriage alliance. Manuel had already married Amalric's cousin, Maria of Antioch, in 1161. After two years, Amalric married Manuel's grandniece, Maria Komnene, in 1167. He also promised to uphold all agreements his brother Baldwin had made.

A formal alliance was made in 1168. The two rulers planned to conquer and divide Egypt. Manuel would take the coastal area, and Amalric would take the interior. In the autumn of 1169, Manuel sent a joint expedition with Amalric to Egypt. A Byzantine army and a naval force of 20 large warships, 150 galleys, and 60 transport ships, led by Andronikos Kontostephanos, joined Amalric at Ascalon. William of Tyre, who helped arrange the alliance, was especially impressed by the large ships used to carry the cavalry.

Attacking a distant state like Egypt was unusual for the Empire. The last time they tried something similar was over 120 years earlier in Sicily. But Manuel's foreign policy was to use the Latins to help the Empire survive. He believed that controlling Egypt would be key in the larger struggle between the Crusader states and the Islamic powers. It was clear that the weak Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt held the key to the Crusader states' future. If Egypt joined forces with the Muslims under Nur ad-Din, the Crusaders would be in trouble.

A successful invasion of Egypt would also benefit the Byzantine Empire. Egypt was a rich province. In Roman times, it supplied much of Constantinople's grain before it was lost to the Arabs in the 7th century. The Empire would gain a lot of money from conquering Egypt, even if they had to share it with the Crusaders. Manuel also wanted to encourage Amalric's plans to keep the Latins from focusing on Antioch. This would also create new chances for joint military actions, keeping the King of Jerusalem in Manuel's debt and allowing the Empire to share in new lands.

The Expedition Fails

The combined forces of Manuel and Amalric besieged Damietta on October 27, 1169. But the siege failed because the Crusaders and Byzantines did not fully cooperate. Byzantine forces claimed Amalric, wanting to keep all the profits, delayed the operation. This caused the emperor's men to run out of supplies and suffer from hunger. Amalric then launched an attack but quickly stopped it by making a truce with the defenders. On the other hand, William of Tyre said the Greeks were also partly to blame.

Whatever the truth, when the rains came, both the Latin army and the Byzantine fleet returned home. Half of the Byzantine fleet was lost in a sudden storm.

Despite the bad feelings from Damietta, Amalric still wanted to conquer Egypt. He continued to seek good relations with the Byzantines for another joint attack, but it never happened. In 1171, Amalric came to Constantinople himself after Egypt fell to Saladin. Manuel held a grand reception that honored Amalric but also showed his dependence. For the rest of Amalric's reign, Jerusalem was like a Byzantine satellite state. Manuel became a protector of the Holy Places and gained more influence in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. In 1177, Manuel sent a fleet of 150 ships to invade Egypt. But it returned home after reaching Acre because Philip of Flanders and many important nobles of the Kingdom of Jerusalem refused to help.

Kilij Arslan II and the Seljuk Turks

Between 1158 and 1162, the Byzantines fought several campaigns against the Seljuk Turks of the Sultanate of Rûm. This led to a treaty that favored the Empire. The agreement stated that certain border regions, including the city of Sivas, should be given to Manuel. It also required the Seljuk Sultan Kilij Arslan II to recognize Manuel as his overlord.

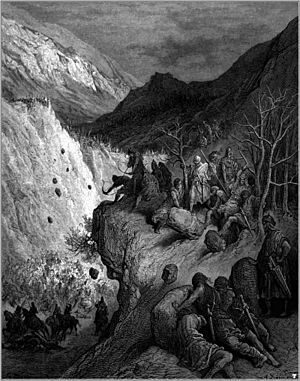

Kilij Arslan II used the peace with Byzantium to his advantage. After Nur ad-Din Zangi, the ruler of Syria, died in 1174, Kilij Arslan took land from the Danishmends. He refused to give some of this land to the Byzantines, even though his treaty required it. Manuel decided it was time to deal with the Turks once and for all. He gathered his entire imperial army and marched towards the Seljuk capital, Iconium (Konya). Manuel's plan was to set up advanced bases at Dorylaeum and Sublaeum. From there, he would quickly attack Iconium.

Manuel's army of 35,000 men was very large and difficult to move. According to a letter Manuel sent to King Henry II of England, the marching column was 10 miles long. Manuel marched towards Iconium through several towns. Just before entering the pass at Myriokephalon, Turkish ambassadors met Manuel. They offered generous peace terms. Most of Manuel's generals and experienced advisors urged him to accept the offer. However, the younger, more aggressive members of his court told him to attack. Manuel took their advice and continued his advance.

Manuel made serious mistakes. For example, he failed to properly scout the path ahead. These mistakes led his forces straight into a classic ambush. On September 17, 1176, Manuel was defeated by Seljuk Sultan Kilij Arslan II at the Battle of Myriokephalon. His army was ambushed while marching through a narrow mountain pass. The Byzantines were trapped by the narrowness of the pass. This allowed the Seljuks to focus their attacks on parts of the Byzantine army, especially the baggage and siege equipment.

The army's siege equipment was quickly destroyed. Manuel was forced to retreat because without siege engines, conquering Iconium was impossible. According to Byzantine sources, Manuel lost his confidence during and after the battle. He was never the same again.

Kilij Arslan II allowed Manuel and his army to leave on the condition that he remove his forts and armies at Dorylaeum and Sublaeum. However, since the Sultan had not kept his part of an earlier treaty, Manuel only ordered the fortifications of Sublaeum to be dismantled, not Dorylaeum.

The defeat at Myriokephalon was embarrassing for Manuel and his empire. The Komnenian emperors had worked hard since the Battle of Manzikert 105 years earlier to restore the empire's reputation. But because of his over-confidence, Manuel showed the world that Byzantium still could not decisively defeat the Seljuks. In Western Europe, Myriokephalon made Manuel seem less powerful.

The defeat at Myriokephalon is often seen as a disaster where the entire Byzantine army was destroyed. Manuel himself compared it to Manzikert. In reality, it was a defeat, but not too costly. It did not greatly weaken the Byzantine army. Most of the losses were among the right wing, which was mostly allied troops, and the baggage train, which was the main target of the Turkish ambush.

The losses to native Byzantine troops were quickly replaced. The next year, Manuel's forces defeated a force of "picked Turks." John Komnenos Vatatzes, sent by the Emperor to stop the Turkish invasion, brought troops from the capital and gathered an army along the way. Vatatzes ambushed the Turks as they crossed the Meander River. The resulting Battle of Hyelion and Leimocheir effectively destroyed them as a fighting force. This showed that the Byzantine army was still strong.

After the victory on the Meander, Manuel himself advanced with a small army to drive the Turks from Panasium. In 1178, a Byzantine army retreated after meeting a Turkish force at Charax. This allowed the Turks to capture many livestock. The city of Claudiopolis in Bithynia was besieged by the Turks in 1179. Manuel had to lead a small cavalry force to save the city. Even as late as 1180, the Byzantines won a victory over the Turks.

The constant warfare affected Manuel's health. He became ill and died in 1180 from a slow fever. Like Manzikert, Myriokephalon caused the balance of power to shift. Manuel never attacked the Turks again. After his death, they began to move further west into Byzantine territory.

Manuel's Chivalric Side

Manuel was a new kind of Byzantine ruler. He was influenced by his interactions with Western Crusaders. He organized jousting matches and even participated in them. This was unusual for Byzantines. He was very strong and brave. Stories say he was so strong that Raymond of Antioch couldn't even lift his lance and shield.

In one famous tournament, he is said to have ridden a fiery horse and knocked down two of the strongest Italian knights. It is also said that in one day, he killed forty Turks with his own hands. In a battle against the Hungarians, he supposedly grabbed a banner and was the first to cross a bridge, almost alone, that separated his army from the enemy. Another story says he fought his way through 500 Turks without getting hurt.

Manuel's Family

Manuel had two wives. His first marriage, in 1146, was to Bertha of Sulzbach. She was the sister-in-law of Conrad III of Germany. Bertha died in 1159. They had two children:

- Maria Komnene (1152–1182), who married Renier of Montferrat.

- Anna Komnene (1154–1158).

Manuel's second marriage was to Maria of Antioch (also called Xene). She was the daughter of Raymond and Constance of Antioch. They married in 1161. They had one son:

- Alexios II Komnenos, who became emperor in 1180.

Manuel also had several children outside of marriage:

- By Theodora Vatatzina:

- Alexios Komnenos (born in the early 1160s). He was recognized as the emperor's son and given a title. He was briefly married to Eirene Komnene, the illegitimate daughter of Andronikos I Komnenos. He was blinded by his father-in-law but lived until at least 1191.

- By Maria Taronitissa:

- Alexios Komnenos, a "cupbearer." He fled Constantinople in 1184 and was involved in the Norman invasion and the siege of Thessalonica in 1185.

- By other women:

- A daughter (name unknown), born around 1150. She married Theodore Maurozomes. Her son was Manuel Maurozomes. His daughter married Kaykhusraw I, the Seljuk Sultan. Her descendants ruled the sultanate from 1220–1246.

- A daughter (name unknown), born around 1155. She was the grandmother of the writer Demetrios Tornikes.

Manuel's Impact and Legacy

Military and Foreign Policy

When he was young, Manuel wanted to restore the Byzantine Empire's power in the Mediterranean by force. By the time he died in 1180, 37 years had passed since he became emperor. During these years, Manuel was involved in conflicts with all his neighbors. Manuel's father and grandfather had worked hard to fix the damage from the Battle of Manzikert. Thanks to them, the empire Manuel inherited was stronger than it had been in a century. Manuel used these strengths fully.

Manuel was an energetic emperor who saw opportunities everywhere. His hopeful attitude shaped his foreign policy. However, despite his military skill, Manuel only partly achieved his goal of restoring the Byzantine Empire. Some people criticize his goals as unrealistic, especially his expeditions to Egypt. His biggest military campaign, against the Turkish Sultanate of Iconium, ended in a humiliating defeat. His biggest diplomatic effort also failed when Pope Alexander III made peace with the German emperor Frederick Barbarossa.

Historian Mark C. Bartusis argues that Manuel tried to rebuild a national army, but his changes were not enough for his goals or needs. The defeat at Myriokephalon showed the weakness of his policies. According to Edward Gibbon, Manuel's victories did not lead to any lasting or useful conquests.

Life Inside the Empire

The historian Choniates criticized Manuel for raising taxes. He said Manuel's reign was a time of too much spending. According to Choniates, the money was spent lavishly, harming his citizens. Whether you read Greek or Latin sources, they all agree that Manuel spent a lot of money. He rarely saved money in one area to develop another. Manuel spent a lot on the army, navy, diplomacy, ceremonies, palace building, his family, and others seeking favors. A lot of this spending was a financial loss to the Empire. This includes the money poured into Italy and the Crusader states, and the sums spent on failed expeditions.

The problems this created were balanced by his successes, especially in the Balkans. Manuel expanded the empire's borders in the Balkan region. This made all of Greece and Bulgaria secure. If he had been more successful in all his ventures, he would have controlled the most productive farmland around the Eastern Mediterranean and Adriatic seas. He would also have controlled all the trade in the area. Even if he didn't reach all his ambitious goals, his wars against Hungary gave him control of the Dalmatian coast, the rich farming region of Sirmium, and the Danube trade route. His Balkan expeditions brought back many slaves and livestock.

This allowed the Western provinces to thrive in an economic revival. This revival had started during his grandfather Alexios I's time and continued until the end of the century. Some argue that Byzantium in the 12th century was richer and more prosperous than at any time in 500 years. There is good evidence of new buildings and churches, even in remote areas. This suggests that wealth was widespread.

Trade was also booming. The population of Constantinople, the empire's biggest commercial center, was between half a million and one million during Manuel's reign. This made it by far the largest city in Europe. A major source of Manuel's wealth was the kommerkion, a customs duty on all imports and exports in Constantinople. The kommerkion was said to collect 20,000 hyperpyra each day.

Constantinople was also growing. Italian merchants and Crusaders on their way to the Holy Land made the city more diverse. The Venetians, Genoese, and others opened the ports of the Aegean Sea to trade. They shipped goods from the Crusader kingdoms and Egypt to the west. They also traded with Byzantium through Constantinople. These traders increased demand in the towns and cities of Greece, Macedonia, and the Greek Islands. This created new sources of wealth in an economy that was mostly based on farming. Thessaloniki, the empire's second city, hosted a famous summer fair. It attracted traders from across the Balkans to its busy markets. In Corinth, silk production fueled a thriving economy. All this shows how successful the Komnenian Emperors were in creating a period of peace and stability in these core territories.

Manuel's Lasting Impact

To the writers at his court, Manuel was the "divine emperor." A generation after his death, Choniates called him "the most blessed among emperors." A century later, John Stavrakios described him as "great in fine deeds." John Phokas, a soldier in Manuel's army, called him the "world saving" and glorious emperor.

Manuel was remembered in France, Italy, and the Crusader states as the most powerful ruler in the world. A Genoese writer noted that with the death of "Lord Manuel of divine memory, the most blessed emperor of Constantinople... all Christendom suffered great ruin and harm." William of Tyre called Manuel "a wise and discreet prince of great magnificence, worthy of praise in every respect," and "a great-souled man of incomparable energy," whose "memory will ever be held in blessing." Manuel was also praised by Robert of Clari as "a right worthy man, [...] and richest of all the Christians who ever were, and the most bountiful."

A clear sign of Manuel's influence in the Crusader states can still be seen in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. In the 1160s, the church's main hall was redecorated with mosaics showing church councils. Manuel helped pay for this work. On the south wall, a Greek inscription reads: "the present work was finished by Ephraim the monk, painter and mosaicist, in the reign of the great emperor Manuel Porphyrogennetos Komnenos and in the time of the great king of Jerusalem, Amalric." Manuel's name was placed first, showing public recognition of his leadership in the Christian world.

Manuel's role as a protector of Orthodox Christians and holy places is also clear. He successfully gained rights over the Holy Land. Manuel helped build and decorate many churches and Greek monasteries in the Holy Land. This included the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Thanks to his efforts, Byzantine clergy were allowed to perform the Greek church service there every day. All this strengthened his position as overlord of the Crusader states. His leadership over Antioch and Jerusalem was secured by agreements with Raynald, Prince of Antioch, and Amalric, King of Jerusalem. Manuel was also the last Byzantine emperor who, thanks to his military and diplomatic success in the Balkans, could call himself "ruler of Dalmatia, Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia, Bulgaria and Hungary."

Manuel died on September 24, 1180. He had just celebrated the engagement of his son Alexios II to the daughter of the King of France. He was buried next to his father in the Pantokrator Monastery in Constantinople. Thanks to the diplomacy and campaigns of Alexios, John, and Manuel, the empire was a great power. It was economically prosperous and secure on its borders. But there were serious problems too.

Inside the empire, the Byzantine court needed a strong leader to keep it together. After Manuel's death, stability was greatly threatened from within. Some of the empire's enemies were waiting for a chance to attack. These included the Turks in Anatolia, whom Manuel had failed to defeat, and the Normans in Sicily, who had tried to invade the empire several times. Even the Venetians, Byzantium's most important Western ally, had poor relations with the empire when Manuel died in 1180.

Given this situation, a strong emperor was needed to protect the Empire from foreign threats and to rebuild the imperial treasury. But Manuel's son was a minor (too young to rule). His unpopular government, led by others, was overthrown in a violent takeover. This troubled succession weakened the family line and unity that the Byzantine state had come to rely on.

Images for kids

-

Letter by Manuel I Komnenos to Pope Eugene III on the issue of the crusades (Constantinople, 1146, Vatican Secret Archives): with this document, the Emperor answers a previous papal letter asking Louis VII of France to free the Holy Land and reconquer Edessa. Manuel answers that he is willing to receive the French army and to support it, but he complains about receiving the letter from an envoy of the King of France and not from an ambassador sent by the Pope.

See also

In Spanish: Manuel I Comneno para niños

In Spanish: Manuel I Comneno para niños