Paleontology in Wyoming facts for kids

Paleontology in Wyoming is all about discovering and studying the amazing ancient life that once lived in the state of Wyoming. It also includes the work done by scientists and museums in Wyoming who study fossils found in other places.

Wyoming is a super cool place for finding fossils! You can find traces of ancient life from billions of years ago, all the way up to more recent times. In fact, Wyoming has so many fossils that one author, Marian Murray, said in 1974 that big museums always send their teams there to look for more. She also mentioned that almost every famous fossil expert in the U.S. has collected fossils in Wyoming. It's a major spot for dinosaur fossils, and these dinosaur bones are now displayed in museums all over the world.

Imagine Wyoming long, long ago. During the Precambrian time, it was covered by a shallow sea. Tiny bacteria lived there, forming dome-shaped structures called stromatolites. This sea stayed for a long time, and later, creatures like brachiopods (shellfish), ostracoderms (armored fish), and trilobites (ancient sea bugs) swam in it. Then, during the Silurian period, the sea dried up, leaving a gap in the rock layers. But it came back during the Devonian and stayed until the Permian, when it started to disappear again.

By the Triassic period, Wyoming had turned into a coastal plain with rivers. Dinosaurs roamed here, leaving their footprints in the mud, which later turned into fossils. In the Jurassic period, parts of the state were covered in sand dunes. Later, during the Late Cretaceous, a huge inland sea called the Western Interior Seaway covered most of Wyoming.

After the dinosaurs, in the early Cenozoic era, Wyoming had big lakes filled with fish like Knightia and thick forests. On land, you would have seen ancient camelids, meat-eating carnivorans, strange creodonts, a seven-foot-tall flightless bird called Gastornis, elephant-like creatures called proboscideans, early equids (horses), primates, rodents, and the massive Uintatherium. During the Ice Age, glaciers carved out parts of Wyoming. Long before scientists arrived, Native Americans knew about these fossils. They used them for practical things and even had myths to explain them. Wyoming became a famous place for dinosaur hunting in the 1870s, especially with discoveries in the Morrison Formation. By the early 1900s, tons of dinosaur fossils had been dug up from Wyoming. Today, the Knightia fish from the Eocene is Wyoming's state fossil, and Triceratops is the state's official state dinosaur.

Contents

Ancient Wyoming: A Journey Through Time

Life in Ancient Seas

During the Precambrian time, Wyoming was covered by a shallow sea. In this sea, tiny living things called stromatolites formed dome-shaped structures. You can still see some of these ancient stromatolites preserved in the Medicine Bow Mountains. Some rock formations might even show traces of other creatures that lived in this sea.

In the early Paleozoic era, Wyoming was still mostly covered by a shallow sea. This sea was home to creatures like brachiopods, which looked a bit like clams, and trilobites, which were ancient arthropods. By the Late Cambrian period, a type of calcareous algae grew in great masses in the sea. Their fossils are preserved in the Gros Ventre Formation. The area where the Bighorn Mountains are now was also a marine environment during the Ordovician period. Armored fish called ostracoderms swam in this sea.

During the Silurian period, the sea left Wyoming, and some of the older rock layers were worn away. But the sea returned during the Devonian period and stayed until the Permian, when it started to slowly disappear again.

Dinosaurs and Ancient Landscapes

As the sea continued to shrink during the Triassic period, much of Wyoming became a coastal plain with rivers flowing through it. In the Late Triassic, dinosaurs left small footprints in western Wyoming. These tracks, called Agialopus wyomingensis, later turned into fossils. Some Triassic red rocks in Wyoming also have strange "scrape marks." These were likely made by a swimming animal, possibly an ancient turtle, similar to tracks found in France.

Moving into the Jurassic period, much of Wyoming was covered in sand dunes. Sea levels changed again, and the sea was home to creatures like belemnites (ancient squid-like animals) and oysters. On land, dinosaurs left many footprints across the floodplains. In the Jurassic, the area now called Dinosaur Canyon was home to early relatives of modern crocodilians and mammals. Flying reptiles called Pterosaurs might have made footprints found in rocks from the Sundance Formation. These tracks are known as Pteraichnus.

During the Cretaceous period, mountains began to form in Wyoming in an event called the Laramide Orogeny. Most of Wyoming was covered by the Western Interior Seaway. A common fish in this sea was Enchodus, a relative of modern salmon. Its long fangs earned it the nickname "the sabre-toothed herring"! These fangs were probably used to catch small prey. Enchodus was so common that about a quarter of the fossils in Wyoming's Pierre Shale are from this fish.

Enchodus was often hunted by Cimolichthys. This fish was also related to salmon but looked more like a barracuda or pike. Cimolichthys was a fierce hunter that went after big prey. Sometimes, trying to swallow something too big was its downfall! One Cimolichthys suffocated when it tried to eat a huge squid called Tusoteuthis longa, which was too big and blocked its gills. A scientist named Michael J. Everhart called this fossil "[o]ne of the strangest 'death by gluttony' occurrences in the fossil record."

The plesiosaur Dolichorhynchops osborni, a long-necked marine reptile, also lived in Wyoming's Cretaceous sea. Its fossils are found more often here than in Kansas. The sea turtle Toxochelys latiremis was also present. One fossil turtle was found with fossilized poop that had fish bones inside. If this poop really belonged to the Toxochelys, it would mean these ancient turtles ate fish, which no modern sea turtles do!

During the Cretaceous, mammals were common in Wyoming, and dinosaurs nested near Powell. It's interesting that Late Cretaceous dinosaur footprints are quite rare in Wyoming compared to other western states. This might be because the ancient environments weren't good for preserving tracks, or maybe scientists just haven't looked in the right places yet.

Wyoming After the Dinosaurs

In the early Cenozoic era, Wyoming was covered in thick forests. The plants from these forests later formed large coal deposits. Huge lakes also appeared in the low areas between the mountains. One fish that lived in these lakes, Knightia eocaena, is now Wyoming's state fossil. The Rocky Mountains were still forming, and this movement of the Earth's crust caused volcanic eruptions.

During the Paleocene period, the Big Horn Basin had a unique group of mammals. In the Eocene period, Wyoming had many large freshwater lakes. A type of blue-green algae called Chlorellopsis grew in these lakes. Its fossils are found in deposits around the lake shores. The Green River area has some of the best-preserved freshwater fish fossils in the world, not far from Bridger.

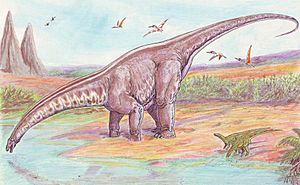

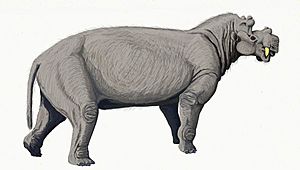

On land, the seven-foot-tall flightless bird Gastornis roamed. Other land animals in Eocene Wyoming included creodonts (ancient meat-eaters) and many different insects. Their remains were found near Henry's Fork, close to the border with Utah. The Bridger Basin was home to creatures like relatives of camels, carnivorans, elephants, horses, primates, rodents, the huge Uintatherium, and even whales! During the Quaternary period, volcanoes continued to be active, and glaciers left large deposits in the western part of the state.

Discovering Wyoming's Past: Scientific Research

One of the first fossil hunting trips to Wyoming happened in 1870. O. C. Marsh led an expedition for Yale University. But it wasn't until 1877 that Wyoming's amazing dinosaur fossils really caught the attention of scientists. Three men were key to this discovery: Arthur Lakes, a professor; O. Lucas, a teacher; and William H. Reed, a foreman for the Union Pacific Railroad.

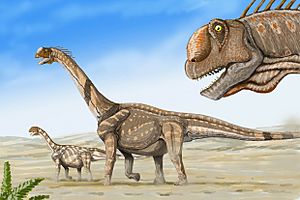

In March 1877, William Reed found fossil bones at Como Bluff while hunting. He was joined by the railroad station's agent, William E. Carlin. They spent weeks collecting fossils but kept their discovery a secret for months. In July, O. C. Marsh heard about their finds. Marsh hired both Reed and Carlin to collect more fossils for him. For the rest of 1877 and early 1878, Reed and Carlin worked at four quarries. They found several Camarasaurus specimens, including a new species called Camarasaurus grandis.

In May 1878, they found a new site for a fifth quarry. There, they discovered the first Jurassic pterosaur (flying reptile) found in North America. They also found a new type of plant-eating dinosaur, Dryosaurus altus. Nearby, they made another important find: Dryolestes priscus, the first Jurassic mammal found in North America. Around this time, Princeton also sent a large expedition to Wyoming, and Samuel W. Williston began his own digs.

Late in 1877, Marsh's scientific rival, Edward Drinker Cope, heard about the fossils at Como Bluff. He quickly sent his own fossil hunters to the area. Reed wrote to Marsh about his struggles to keep Cope's men away from his digging sites. William Carlin even quit working for Marsh and joined Cope's team! Since Carlin was in charge of the railway station, he used his power to make things difficult for Reed. Reed was often "stuck boxing his material for shipment to Marsh outside in the cold." Marsh sent more help, but no one stayed long. By spring 1879, Reed was mostly on his own, working hard to dig up fossils before Cope's men could get them.

In mid-May 1879, Marsh told Arthur Lakes to leave Colorado and help Reed at Como Bluff. This partnership was very successful that year. They found a seventh quarry and dug up a small ornithopod skeleton. In early July, they found a ninth site that became one of the best places on Earth for Jurassic mammal fossils. Quarry 9 produced more fossils than any other site in the Morrison Formation.

In September, they made another big discovery. By the end of the month, they had found a new species of sauropod (long-necked dinosaur), Brontosaurus excelsus. This dinosaur's skeleton was later put on display at the Yale Peabody Museum. This species is now known as Apatosaurus excelsus. In August, William Reed's assistant, E. G. Ashley, found a twelfth quarry site. There, they discovered fossils of a new Stegosaurus species, S. ungulatus. In September, they found a thirteenth quarry that had more dinosaur skeletons than any other. Camptosaurus and Stegosaurus were the most common. New dinosaurs found here included Camarasaurus lentus, Camptosaurus dispar, and Coelurus fragilis.

The next year, Marsh's team focused on quarries nine and thirteen. Later that year, Arthur Lakes quit. The following year, Reed's brother visited but sadly died while swimming. After this tragedy, Reed lost his passion for working at Como Bluff and quit in spring 1883. After that, Marsh's work at Como Bluff was led by E. G. Kennedy and Fred Brown. They continued to focus on quarries 9 and 13. By June 1889, after twelve years, the fieldwork at Como Bluff ended. Marsh's work there uncovered the largest collection of Jurassic fossils known in the world at that time. By 1918, when Samuel W. Williston finished his work in Wyoming, hundreds of tons of dinosaur bones had been found in the state's rocks.

Another important discovery in Wyoming paleontology happened in 1932. Edward Branson and Maurice Mehl reported finding fossil footprints in Wyoming's Tensleep Sandstone. These tracks were named Steganoposaurus belli. They were probably made by a web-footed animal about three feet long. Later research suggested these footprints were left by reptiles similar to Hylonomus, not amphibians, because the toes were pointed like a reptile's. Small dinosaur footprints from the Late Triassic were also found in western Wyoming during the 1930s. They were formally described as Agialopus wyomingensis.

In 1940, C. L. Gazin led an expedition for the Smithsonian Institution into Wyoming. Their biggest find was a nearly complete skeleton of Uintatherium. While Uintatherium fossils are somewhat common, the one Gazin's team found was incredibly complete and well-preserved. Only a few parts were missing. The fossil was on a steep hillside. To get it out, the team had to drive a truck up a dry creek bed and drag the remains out on canvas. The fossils were so many and so big that they filled four crates, each weighing 500 pounds! The bones were then shipped to Washington, D.C..

In 1953, C. L. Gazin led another Smithsonian expedition to Wyoming. Their digs in the Bison Basin uncovered jaws and teeth from at least four species of plesiadapids, which were early primates related to modern lemurs. Pronothodectes was the largest and most ancient plesiadapid they found. They also found fossils of early "sub-ungulates" (hoofed animals) and plant-eating condylarths. One of these, Phenacodus, was over four feet long, which was unusually large for its group. Finally, the expedition also found fossils of meat-eating creodonts and bear-like clenodonts.

More recently, in 1977, Terry Logue reported finding possible fossil pterosaur footprints in the Sundance Formation in Wyoming. Later, on February 18, 1987, the Eocene fish Knightia was named the Wyoming state fossil. In 1994, Triceratops was chosen as the state dinosaur of Wyoming.

Places to Visit: Protected Areas

Famous Paleontologists from Wyoming

Walter W. Granger, a famous paleontologist, passed away in Lusk on September 6, 1941, at the age of 68.

Explore More: Natural History Museums

- Paleon Museum, Glenrock, Wyoming

- Tate Geological Museum, Casper

- Draper Museum of Natural History, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody

- Natural History Museum of Western Wyoming College, Rock Springs

- University of Wyoming Geological Museum, Laramie

- Wyoming Dinosaur Center, Thermopolis, Wyoming

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |