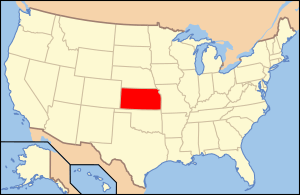

Paleontology in Kansas facts for kids

Paleontology in Kansas is all about studying the amazing fossils found in the U.S. state of Kansas. Kansas has given us some of the most incredible fossil discoveries in American history. The fossil record in Kansas covers a huge amount of time, from the Cambrian period to the Pleistocene Ice Age.

For a long time, from the Cambrian to the Devonian periods, Kansas was covered by a shallow sea. Later, during the Carboniferous period, the sea level went up and down. When the sea was low, Kansas had rich, green swamps where early amphibians and reptiles lived. Seas covered most of the state again during the Permian period. On land, thousands of different insect species thrived. The famous flying reptile, Pteranodon, is best known from fossils found here.

In the early part of the Cenozoic era, Kansas became a savannah (a grassy plain). Later, during the Ice Age, glaciers briefly touched the state. At that time, Kansas was home to camels, mammoths, mastodons, and saber-toothed cats. Some local fossils might have even inspired Native Americans to think certain hills were home to sacred spirit animals. Big scientific discoveries in Kansas include the pterosaur Pteranodon and a fossil of the fish Xiphactinus that died while swallowing another fish!

Contents

Ancient Life in Kansas

Kansas has no fossils from the Precambrian era, so its fossil story starts in the Paleozoic era. From the Cambrian to the Devonian periods, Kansas was under a shallow sea. Not many fossils from Cambrian life in Kansas have been found.

During the Carboniferous period, sea levels in Kansas changed a lot. When the sea was present, it was full of many different kinds of marine (sea) invertebrates (animals without backbones). In the later part of the Carboniferous, called the Pennsylvanian, nautiloids (like modern squid with shells) lived in Franklin County. Other marine invertebrates were found in Anderson County.

Paleoniscid fishes swam in the waters of Douglas County. Some of their fossils even show their soft body parts! Fish fossils from this time were also found in Anderson County. During drier times, Kansas had huge coastal swamps filled with many plants, like ferns and scale trees. These swamps created large coal deposits. Plant fossils were also found in southern Labette County and Montgomery County. The plant Walchia grew in Anderson County, but its fossils are rare.

On land, Kansas was home to invertebrates like scorpions. It also had amphibians and early reptiles. These ancient four-legged animals left behind footprints that turned into fossils. Some of these tracks belong to the Limnopus group. Other tracks, called Wakarusopus, were found in Douglas County. They were made by a giant amphibian that would have weighed hundreds of pounds! Pennsylvanian amphibian fossils were also found in Anderson County. Primitive reptiles left fossils near Garnett in Anderson County.

Most of the Permian rocks in Kansas were formed in marine environments. This sea was home to algae, brachiopods (shellfish), bryozoans (tiny colonial animals), fusulinids (single-celled organisms), ostracods (small crustaceans), pelecypods (clams), and trilobites (ancient arthropods). The brachiopod Chonotes was very common. On land, the area around Elmo in Dickinson County had more than ten thousand species of insects! They lived among conifers (cone-bearing trees) that left fossils in the Garnett area.

For the last 70 million years of the Cretaceous period, Kansas was covered by a shallow sea called the Western Interior Sea. The seafloor was flat and probably never deeper than 600 feet. Many different invertebrates lived on the bottom and in the water. These included ammonites (shelled creatures like squid), giant clams, crinoids (sea lilies), rudists (another type of clam), and squid. Vertebrates included bony fishes, mosasaurs (marine reptiles), plesiosaurs (long-necked marine reptiles), sharks, and turtles. Even dinosaurs like Niobrarasaurus coleii sometimes floated hundreds of miles into the sea after they died, becoming fossils. Cretaceous plants left fossil leaves in Ellsworth County. Flying above the sea was the huge pterosaur Pteranodon, which might have flown across the entire sea.

During the Tertiary period, Kansas was a savannah with more rain and a milder climate. Later in the Cenozoic era, during the Quaternary period, glaciers briefly moved into the northeastern part of the state. Much of Kansas during the Quaternary was covered in pine forests and savannahs. These places were home to creatures like camels, saber-toothed cats, Ground Sloths, mammoths, and mastodons. Other animals from the Pleistocene in Kansas included bison, horses, and peccaries (pig-like animals). Their fossils were found in the western half of the state.

Discovering Kansas Fossils

Scientific Research

In 1859, Joseph Leidy reported finding two shark teeth and a dorsal fin spine from three different kinds of sharks in Carboniferous rocks in Kansas. These were the first vertebrate (backboned animal) fossils from the state to be written about in scientific papers. Later, in 1865, Judge E. P. West found many fossil plants in Ellsworth County. Each fossil was a leaf preserved inside a round ironstone rock. After West's discovery, Charles H. Sternberg worked in the area for several years, finding hundreds of these fossil rocks.

In 1867, a U.S. Army surgeon named Dr. Theophilus Turner found a nearly complete plesiosaur skeleton in what is now Logan County. He was stationed at Fort Wallace. This was the first plesiosaur fossil of its kind found in all of North America! Dr. Turner gave some of the bones to John LeConte, who was part of a railroad survey. LeConte then gave the bones to paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope. Cope realized they were from a very large plesiosaur. He wrote to Dr. Turner asking for the rest of the skeleton. Turner sent the fossils, and in March 1868, Cope received them. Just two weeks later, Cope presented his findings. He named the creature Elasmosaurus platyurus. However, in his rush, he famously put the head on the end of the tail instead of the neck!

In 1870, O. C. Marsh led a fossil hunting trip for Yale University. In November, they visited the area around Fort Wallace. They spent days looking for fossils in modern Wallace and Logan Counties, near the Smoky Hill River. Despite the cold, they found several important fossils. One was a nearly complete skeleton of the mosasaur Clidastes, which took four days to dig out. Marsh's team also found parts of two pterosaur wing bones. These were the first scientifically recorded fossils of the pterosaur that would later be named Pteranodon in 1876.

In 1877, Benjamin Franklin Mudge was one of the first researchers to confirm the presence of fossil "shark mummies" from the Cretaceous shark Cretoxyrhina. One such fossil was found in Gove County at Hackberry Creek in 1891 by George Hazelius Sternberg. Later, his son George F. Sternberg found another shark mummy in the same area.

In 1894, Othniel Charles Marsh named the fossil footprint group Limnopus for tracks found in a Carboniferous-aged coal deposit.

Early in the 1900s, the sixth discovery of a labyrinthodont amphibian was made somewhere in Kansas. The fossil included part of a skull and jaws with fourteen teeth. A new genus and species, Erpetosuchus kansensis, was named for it. The fossils were said to be from Washington County, but the rocks there don't match where such a fossil would be found. The true origin of these fossils remains a mystery. In early 1962, reports came out about two new places in Kansas and Oklahoma rich in fossil insects. The older Kansas site was called Wellington XVIII and was in Sumner County.

In 1940, R. W. Brown first reported finding fossil pearls in the Niobrara and Benton Formations in Kansas. Many of these were first collected by George F. Sternberg west of Hays. The fossil pearls have lost their shiny outer layer, called nacre, making them dull gray or brown. Sternberg donated 50 of these pearls to the Smithsonian Institution.

In spring 1952, a team from the American Museum of Natural History was working with George Sternberg in Gove County. A team member named Walter Sorenson found a fossil tail fin from the fish Xiphactinus audax sticking out of the rock. The museum workers didn't have time to dig it out, so they left it for Sternberg and his team. Sternberg and others finished uncovering the Xiphactinus. They found it was one of the best-preserved ever! Even better, the 13-foot-long Xiphactinus had an entire 6-foot Gillicus arcuatus inside its ribcage. The Gillicus was not digested, meaning the Xiphactinus must have died very quickly after eating its last meal. It might have died from internal injuries because its prey was so big, or from the struggles of the Gillicus. This fossil is now famous as the "fish-in-a-fish" specimen. It is kept at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History as FHSM VP-333 (Xiphactinus) and FHSM VP-334 (Gillicus).

In 1956, Kansas fossil hunter Marion Charles Bonner donated a nearly complete fossil of the short-necked plesiosaur Dolichorhynchops osborni to the Sternberg Museum of Natural History. It is cataloged as FHSM VP-404.

In 1963, George Sternberg found a fossil in Trego County northwest of WaKeeney. This fossil, FHSM VP-401, is the most complete skeleton known of the mosasaur Ectenosaurus clidastoides. Only the tail and back flippers were missing. What's really cool is that this fossil even preserved actual impressions of the animal's skin!

People Who Studied Fossils in Kansas

Births

- Barnum Brown was born in Carbondale on February 12, 1873.

- Carl Owen Dunbar was born in Hallowell on January 1, 1891.

- Leo George Hertlein was born in Pratt County in 1898.

- Claude W. Hibbard was born in Toronto on March 21, 1905.

- Charles Mortram Sternberg was born in Lawrence in 1885.

Deaths

- Benjamin Franklin Mudge died in Manhattan on November 21, 1879 at age 62.

- Elmer S. Riggs died in Sedan on March 25, 1963 at age 94.

Natural History Museums in Kansas

- Fick Fossil & History Museum, Oakley

- Johnston Geology Museum, Emporia

- Sternberg Museum of Natural History, Hays

- McPherson Museum, McPherson

- Museum at Prairiefire, Overland Park

- University of Kansas Natural History Museum, Lawrence