Textile manufacture during the British Industrial Revolution facts for kids

The textile industry was a huge part of the Industrial Revolution in Britain. This big change happened mostly in places like Lancashire and the towns around the Pennines mountains. The main things that drove the Industrial Revolution were making textiles, working with iron, using steam power, and later, new things like electricity and the telegraph. These inventions made workers much more productive. They also made life better by making travel, transport, and communication much faster.

Before the 1700s, people made cloth by hand in their homes. They used packhorses or canals to move goods around the country. In the mid-1700s, skilled workers started inventing new ways to make things faster. Fabrics like silk, wool, and linen were popular. But then, cotton became the most important textile.

New machines for carding (preparing fibers) and spinning (making thread) were invented. These machines, like the spinning mule and water frame, were made possible by new ways of working with cast iron. The first machines were put in mills powered by water from streams. As more power was needed, people started using steam engines. These engines powered machines on every floor of the mill. More power also led to better power looms for weaving cloth in special buildings called weaving sheds. The huge amount of cloth made in towns around Manchester created a need for big markets and warehouses. This new technology was also used in mills that made wool.

Contents

- What Started the Industrial Revolution?

- How Did Industry and Inventions Change Things?

- Early Inventions and Their Impact

- Working in the Mills

- A Look at an Early Spinning Mill (1771)

- A Look at a Mid-Century Spinning Mill (1840)

- How Technology Spread to Other Countries

- Art and Literature About the Revolution

- Images for kids

What Started the Industrial Revolution?

The start of the Industrial Revolution is linked to a few key inventions from the late 1700s:

- John Kay's Flying Shuttle (1733): This invention made it possible to weave cloth much faster and wider. It also helped make weaving a machine-driven process later on.

- Cotton Spinning Machines:

- Richard Arkwright invented the water frame.

- James Hargreaves invented the Spinning jenny.

- Samuel Crompton combined these two to create the Spinning mule. This invention was patented in 1769. After the patent ended in 1783, many cotton mills were built quickly. Similar machines were later used for spinning wool and flax (for linen).

- James Watt's Improved Steam Engine (1775): At first, this engine was mainly used to pump water out of mines or for water supply. But from the 1780s, it was used to power machines in factories. This allowed factories to grow quickly in places without waterpower. Early steam engines had problems with speed control, which could break threads. But this was solved by using the engine to pump water over a water wheel, which then drove the machines.

- Changes in the Iron Industry: Coke (a type of fuel made from coal) started to replace charcoal in all steps of making iron. This had already happened for lead and copper. But now it was used for making wrought iron. Steam engines also helped the iron industry by powering air blasts for furnaces, making them hotter. This meant more lime could be used to remove sulfur from coal or coke. Iron production greatly increased after the 1750s.

These three areas – textiles, steam power, and iron – were the main "leading sectors" that helped the Industrial Revolution take off. Later inventions, like the power loom and Richard Trevithick's high-pressure steam engine, were also very important. Using steam engines meant factories could be built where it was most convenient, not just where there was water for a watermill.

How Did Industry and Inventions Change Things?

Before the 1760s, making textiles was a "cottage industry." This meant people worked from their homes, mostly with flax and wool. A typical family might have one handloom, operated by the man and a boy. The women and girls would make enough yarn for that loom.

People had known how to make textiles for centuries. India had a cotton industry and made cotton textiles. When raw cotton was sent to Europe, it was used to make a fabric called fustian.

Two main types of spinning wheels were used: the simple wheel and the more advanced Saxony wheel. These worked well for handlooms. But after John Kay invented the flying shuttle in 1734, looms could make cloth twice as fast. This meant spinners couldn't make thread fast enough!

Cloth production then moved out of homes and into "manufactories" or mills. Spinning was the first part of the process to move into mills. Weaving moved later. By the 1820s, all cotton, wool, and worsted (a type of wool yarn) were spun in mills. But the yarn was still sent to weavers who worked from their homes. A mill just for weaving was called a weaving shed.

Early Inventions and Their Impact

The East India Company's Role

In the late 1600s, the East India Company started making a lot of finished cotton goods in South Asia for the British market. These imported fabrics, like Calico and chintz, were cheaper than British wool and linen. This made local weavers and farmers upset. They asked Parliament to ban these imports.

Parliament passed the Calico Acts in 1700 and 1721. These laws banned the import and sale of pure cotton cloth. But they did not stop the import of raw cotton or the sale of Fustian (a mix of cotton and linen).

Because raw cotton was allowed, two thousand bales of cotton were imported each year from Asia and the Americas. This started a new British textile industry, first making fustian. More importantly, it led to the invention of many new machines for spinning and weaving cotton. This machine-based production grew in new cotton mills. By the 1770s, seven thousand bales of cotton were imported yearly. New mill owners then pushed Parliament to allow them to make and sell pure cotton cloth, so they could compete with imports from the East India Company.

Indian cotton textiles, especially from Bengal, were still better and cheaper than British ones until the 1800s. To compete, British merchants invested in machines that saved labor. The British government also used "protectionist" policies, like bans and tariffs (taxes on imports), to limit Indian goods. At the same time, the East India Company's rule in India led to its "deindustrialization" (loss of its own industries). This opened up India as a market for British goods. The money made in Bengal after 1757 was used by the East India Company to invest in British industries, like textile manufacturing. This greatly helped the Industrial Revolution. Britain eventually became the world's top cotton textile maker in the 1800s.

Britain's Own Innovations

In the 1700s and 1800s, much of the imported cotton came from plantations in the American South. But during times of trouble, like the American Revolutionary War and the American Civil War, Britain relied more on cotton from India. Ports on Britain's west coast, like Liverpool, Bristol, and Glasgow, became important centers for the cotton industry.

Lancashire became a hub for the new cotton industry because its damp climate was good for spinning yarn. At first, cotton thread wasn't strong enough for the "warp" (the lengthwise threads in weaving), so wool or linen had to be used. Lancashire already had a wool industry. Glasgow also benefited from the damp climate.

Early weaving improvements were held back because there wasn't enough thread. Spinning was slow, and weavers needed more cotton and wool thread than their families could make. In the 1760s, James Hargreaves improved thread production with his Spinning Jenny. By the end of the decade, Richard Arkwright developed the water frame. This invention had two big effects: it made stronger thread, so the cotton industry no longer needed wool or linen for warp. It also moved spinning out of homes and into special places with fast-flowing streams to power the bigger machines. The Western Pennines in Lancashire became the center for cotton. Soon after, Samuel Crompton combined the Spinning Jenny and Water Frame to make his Spinning Mule. This machine made even stronger and finer cotton thread.

The textile industry also benefited from other inventions. In 1691, Thomas Savery made a vacuum steam engine. His design was improved by Thomas Newcomen in 1698. In 1765, James Watt made Newcomen's engine even better, creating an external condenser steam engine. Watt kept improving his design, and in 1775, he partnered with businessman Matthew Boulton. Together, they made steam engines that industries could use.

Before the 1780s, most fine cotton muslin in Britain came from India. But by the late 1700s, British "mull muslin" could compete in quality with Indian muslin due to new techniques.

Timeline of Important Inventions

- 1734: In Bury, Lancashire, John Kay invented the flying shuttle. This was one of the first inventions for the cotton industry. It made it possible for one weaver to make wider cloth much faster on a loom. Workers worried about losing their jobs, so this technology wasn't used everywhere right away. But the faster production meant more demand for spun cotton.

- 1738: Lewis Paul and John Wyatt patented the Roller Spinning machine. This machine used two sets of rollers moving at different speeds to twist and spin yarn quickly and efficiently. This was later used in the first cotton spinning mill during the Industrial Revolution.

- 1742: Paul and Wyatt opened a mill in Birmingham using their new machine, powered by a donkey. It didn't make money and closed soon.

- 1743: A factory in Northampton opened, using 50 spindles on five of Paul and Wyatt's machines. This one was more successful and ran until 1764.

- 1748: Lewis Paul invented the hand-driven carding machine. This machine had wire slips around a cylinder. Richard Arkwright and Samuel Crompton later improved his invention.

- 1758: Paul and Wyatt improved their roller spinning machine and got a second patent. Richard Arkwright later used this as a model for his water frame.

The Revolution Begins

- 1761: The Duke of Bridgewater's canal opened, connecting Manchester to the coal fields of Worsley. This helped cotton mills get coal and move goods.

- 1762: Matthew Boulton opened the Soho Foundry engineering works in Handsworth, Birmingham. These events helped build cotton mills and move production out of homes.

- 1764: Thorp Mill in Royton, Lancashire, became the world's first water-powered cotton mill. It was used for carding cotton.

- 1764: The multiple-spindle Spinning Jenny was invented by James Hargreaves. This machine greatly increased how much thread one worker could produce. Other people used his idea without permission since he didn't patent it until 1770. By the time he died, over 20,000 spinning jennies were in use.

- 1771: Richard Arkwright built his first spinning mill, Cromford Mill, in Derbyshire. It used his invention, the water frame, powered by waterwheels. This meant mills needed to be near a good water supply. Arkwright built homes for his workers, creating a large industrial community. He protected his inventions and expanded his business.

- 1775: Matthew Boulton and James Watt started making the more efficient Watt steam engine, which used a separate condenser.

- 1779: Samuel Crompton of Bolton combined parts of the spinning jenny and water frame to create the spinning mule. This machine made stronger thread than the water frame. Early mules were great for making yarn for muslin. Like Kay and Hargreaves, Crompton didn't make much money from his invention and died poor.

- 1783: A mill was built in Manchester at Shudehill, powered by a large waterwheel. A steam pump returned water to the higher reservoir to keep the wheel turning.

- 1784: Edmund Cartwright invented the power loom. His first attempt to use this technology failed, but others improved on his ideas.

- 1790s: Industrialists like John Marshall in Leeds started applying cotton techniques to other materials, like flax.

- 1803: William Radcliffe invented the dressing frame, which helped power looms work continuously.

Later Developments

With the Cartwright Loom, the Spinning Mule, and the Boulton & Watt steam engine, the main parts for a machine-driven textile industry were in place. After this, there weren't many new inventions, but constant improvements to make things cheaper and better. Better transport, like canals and later railways, made it easier to bring in raw materials and send out finished cloth.

Water power was first helped by steam-driven pumps, then completely replaced by steam engines. For example, Quarry Bank Mill in Cheshire was first powered by a water wheel. But in 1810, they added steam engines. In 1830, the average mill engine was 48 horsepower, but Quarry Bank Mill installed a new 100-horsepower water wheel. This changed again in 1836 when a mill in Preston got a 160-horsepower engine. William Fairbairn improved how power was sent to machines within the mill. In 1815, he replaced heavy wooden shafts with lighter wrought iron ones that worked faster and used less power.

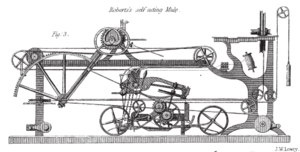

Roberts' Power Loom

In 1830, Richard Roberts made the first power loom with a cast-iron frame, called the Roberts Loom. In 1842, the Lancashire Loom was made. It was a semi-automatic power loom. It could work by itself, but had to be stopped to change empty shuttles. This loom was the main type used in the Lancashire cotton industry for 100 years. Then, the Northrop Loom, invented in 1894, took over because it could automatically refill the weft (crosswise threads).

| Year | 1803 | 1820 | 1829 | 1833 | 1857 |

| Looms | 2,400 | 14,650 | 55,500 | 100,000 | 250,000 |

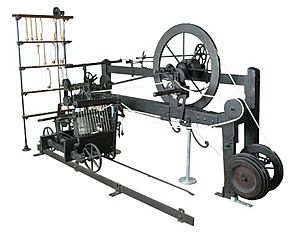

Roberts' Self-Acting Mule

Also in 1830, Richard Roberts patented the first self-acting mule. Before 1830, a spinner had to manually push the mule during part of its operation. After Roberts' invention, the mule could be operated by less skilled workers. Older mules had up to 400 spindles, but self-acting mules could have up to 1,300 spindles.

This new technology saved a lot of time. In the 1700s, a worker using a hand-powered spinning wheel would take over 50,000 hours to spin 100 pounds of cotton. By the 1790s, a mule could spin the same amount in 300 hours. With a self-acting mule, one worker could do it in just 135 hours!

Working in the Mills

Work changed a lot during the Industrial Revolution, moving from skilled craft work done at home to factory work. This shift happened between 1761 and 1850. Textile factories organized workers' lives very differently. Handloom weavers worked at their own speed, with their own tools, in their own homes. Factories, however, set strict work hours, and the machines controlled the pace of work. Factories brought many workers together in one building to work on machines they didn't own.

Factories also led to a greater "division of labor." This means workers did fewer, more specific tasks. Children and women also became part of the factory production process. Some people, like Friedrich Engels, a mill owner in Manchester, were upset by these changes. He wrote that family life was "turned upside down" because women's wages were lower than men's, sometimes forcing men to stay home with children while their wives worked long hours. Factories became more popular than manual craftsmanship because they produced more efficiently per worker, keeping prices low for the public, and had more consistent product quality. Factory owners forced strict work rules on their employees. Engels found working conditions were poor and poverty was very high. His research greatly influenced his and Marx's book, 'Das Kapital'.

Sometimes, workers protested against low wages. The first big strike in Scotland was by the Calton weavers in Glasgow in 1787. Soldiers were called in, and three weavers were killed. Protests continued. In Manchester in 1808, 15,000 protesters were fired on by soldiers, and one man died. A strike followed, which ended with a small wage increase.

In the 1842 General Strike, half a million workers demanded the "Charter" (a list of political demands) and an end to pay cuts. Again, soldiers were called in, and strike leaders were arrested. But some worker demands were met.

Early textile factories employed many children, but this number went down over time. In 1788, two-thirds of workers in 143 water-powered cotton mills in England and Scotland were children. Sir Robert Peel, a mill owner who became a reformer, helped pass the 1802 Health and Morals of Apprentices Act. This law aimed to stop poor children from working more than 12 hours a day in mills. Children started working in mills as young as four, cleaning under machines until they were eight. Then they became "little piecers" until they were 15. During this time, they worked 14 to 16 hours a day and were beaten if they fell asleep. These children were sent to mills in places like Derbyshire, Yorkshire, and Lancashire from workhouses in London and other southern towns. Litton Mill is a well-known example. More laws followed. By 1835, the number of workers under 18 in cotton mills in England and Scotland had dropped to 43%. Most adult cotton factory workers in the mid-1800s had started as child laborers. The growth of this experienced adult workforce helped reduce the need for child labor in textile factories.

A Look at an Early Spinning Mill (1771)

Cromford Mill was one of Arkwright's first mills and became a model for others. It had a constant supply of warm water from a sough (a drain from nearby lead mines) and another brook. It was a five-story mill. Starting in 1772, the mills ran day and night with two 12-hour shifts.

It began with 200 workers, more than the local area could provide. So Arkwright built houses for them nearby, making him one of the first manufacturers to do so. Most employees were women and children, some as young as 7. Later, the minimum age was raised to 10, and children were given 6 hours of education a week so they could keep records that their parents, who couldn't read or write, could not.

The first step in spinning is carding. At first, this was done by hand. But in 1775, Arkwright got a second patent for a water-powered carding machine, which greatly increased production. He soon built more mills on the site and eventually employed 1,000 workers at Cromford. By the time he died in 1792, he was the richest person in Britain who didn't have a noble title.

The gate to Cromford Mill was shut exactly at 6 AM and 6 PM every day. Any worker who didn't get through it not only lost a day's pay but was also fined another day's pay. In 1779, Arkwright put a cannon, loaded with grapeshot, just inside the factory gate. This was a warning to textile workers who might riot, as they had burned down another of his mills in Birkacre, Lancashire. The cannon was never used.

The mill building is a Grade I listed building, meaning it's very important historically. It was first listed in June 1950.

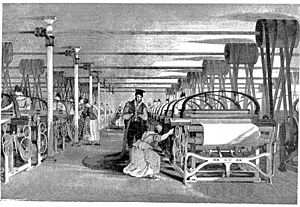

A Look at a Mid-Century Spinning Mill (1840)

Brunswick Mill, Ancoats is a cotton spinning mill in Ancoats, Manchester. It was built around 1840 as part of a group of mills along the Ashton Canal. At that time, it was one of the country's largest mills. It was built around a square courtyard, with a seven-story building facing the canal used for spinning. The preparation work was done on the second floor, and the self-acting mules with 400 spindles were placed across the floors above. Other parts of the mill held blowing rooms and other processes like winding. The four-story building facing Bradford Road was used for storage and offices.

The mill was built by David Bellhouse, and it's thought that William Fairbairn helped with the design. It's made of brick with slate roofs. Fireproof construction was standard by then. Brunswick Mill used cast iron columns and beams, and each floor had arched brick ceilings. There was no wood in the main structure. It was powered by a large double beam engine.

In 1850, the mill had about 276 carding machines and 77,000 mule spindles, plus many other machines for preparing cotton. The building was well-made and successfully switched to "ring spinning" in 1920. It was also the first mill to use mains electricity as its main power source. The mill building was listed as a Grade II listed building in June 1994.

How Technology Spread to Other Countries

While Britain learned from experts from other countries (like Lewis Paul), it was very protective of its own inventions. Engineers who knew how to build textile mills and machinery were not allowed to emigrate (move away), especially to the new America.

Early American Mills

- Horse Power (1780–1790): The first cotton mills in the United States used horses for power. The first one was the Beverly Cotton Manufactory in Beverly, Massachusetts, started in 1788. It used a spinning jenny, a carding machine, and other tools. The mill was built in a rural area with natural water, but this water was used for the horses and cleaning, not for powering machines.

The designs of the Beverly mill were kept secret to stop competitors from stealing ideas. All the early work was done behind closed doors, with owners even experimenting with equipment on their own properties. No detailed articles were published about how their process worked. Also, the mill's horse-powered technology was quickly replaced by newer water-powered methods.

- Samuel Slater: After the United States was formed, an engineer named Samuel Slater, who had worked for Arkwright's partner, managed to get around the ban. In 1789, he took his knowledge of designing and building factories to New England. He soon started building textile mills that helped America have its own industrial revolution.

Local inventions also helped. In 1793, Eli Whitney invented and patented the cotton gin, which made processing raw cotton over 50 times faster.

1800s: Technology Reaches Russia

In the mid-1800s, some of the technology and tools were sold and sent to Russia. The Morozovs family, a famous Russian merchant and textile family, started a private company in central Russia that made dyed fabrics on a large scale. Savva Morozov studied the process at the University of Cambridge in England. Later, with his family's help, he expanded their business, making it one of the most profitable in the Russian Empire.

Art and Literature About the Revolution

The Industrial Revolution and its impact on textile workers inspired many artists and writers:

- William Blake: "And did those feet in ancient time" (also known as "Jerusalem") (1804) and other works.

- Mrs Gaskell: Mary Barton (1848), North and South (1855).

- Charlotte Brontë: Shirley (1849).

- Cynthia Harrod-Eagles wrote fictional stories about the early factories and events of the Industrial Revolution in her The Morland Dynasty series (Volumes 8-13, 15 and 16).

- Textile workshops and the Calico Acts are featured in the board game John Company.

Images for kids

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |