History of photography facts for kids

The history of photography is all about how we learned to capture images using light. It started with two big ideas: how a camera obscura projects images, and how some materials change when light hits them. Before the 1700s, there's no record of anyone trying to capture pictures with light-sensitive stuff.

Around 1717, Johann Heinrich Schulze made shapes of letters appear on a bottle using a special liquid that reacted to light. But he didn't find a way to make them last. Then, around 1800, Thomas Wedgwood tried to capture camera images permanently. He made detailed pictures without a camera (called photograms), but he and his friend Humphry Davy couldn't make them stay.

In 1826, Nicéphore Niépce finally managed to fix a camera image. But it took many hours, or even days, of exposure. His first results were quite blurry. Niépce's partner, Louis Daguerre, then created the daguerreotype process. This was the first widely known and successful way to take photos. Daguerreotypes only needed a few minutes of exposure and made clear, detailed pictures. This amazing invention was shown to the world in 1839. Many people see this year as the start of practical photography.

Soon, the metal-based daguerreotype had a rival: the paper-based calotype negative and salt print processes. These were invented by William Henry Fox Talbot and shown in 1839. Later inventions made photography even easier and more flexible. New materials cut down exposure time from minutes to seconds, or even tiny fractions of a second. Also, new ways of making photos were cheaper, more sensitive, or simpler to use. From the 1850s, the collodion process used glass plates. It offered the high quality of daguerreotypes and the ability to make many copies like calotypes. This process was popular for decades. Later, Roll film made photography easy for everyday people. By the mid-1900s, amateurs could take pictures in natural color as well as black-and-white.

In the 1990s, electronic digital cameras changed photography forever. In the early 2000s, traditional film photography became less common. Digital cameras offered many benefits, and their picture quality kept getting better. Now, cameras are a standard part of smartphones. Taking pictures and sharing them online instantly has become a daily activity for billions of people worldwide.

Contents

- What Does "Photography" Mean?

- How the Camera Started

- Early Discoveries of Light-Sensitive Materials

- First Attempts at Capturing Images (1700-1802)

- Niépce's First Permanent Pictures (1816-1833)

- Early Black-and-White Photography (1832-1840)

- Photography in the Mid-to-Late 1800s

- Photography Becomes Popular

- Seeing in 3D: Stereoscopic Photography

- The Invention of Color Photography

- How Digital Photography Developed

- Gallery of Historical Photos

- See also

What Does "Photography" Mean?

The word "photography" was probably first used by Sir John Herschel in 1839. It comes from two Greek words: φῶς (phōs), which means "light," and γραφή (graphê), meaning "drawing" or "writing." So, photography means "drawing with light."

How the Camera Started

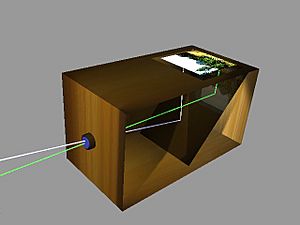

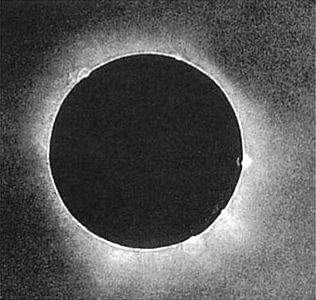

A natural event called a camera obscura, or pinhole image, can project a reversed image through a small hole onto a surface. People might have known about this even in ancient times. The oldest known written record of the camera obscura is from Chinese writings by Mozi in the 4th century BCE. Until the 1500s, the camera obscura was mainly used to study light and stars. It was especially useful for safely watching solar eclipses without hurting your eyes.

In the late 1500s, some improvements were made. A biconvex lens was added to the opening by Gerolamo Cardano in 1550. Also, a diaphragm was used to control the opening by Daniel Barbaro in 1568. These changes made the image brighter and sharper. In 1558, Giambattista della Porta suggested using the camera obscura to help artists draw. Artists widely adopted this idea. From the 1600s, portable camera obscuras became common. First, they were like tents, then they became boxes. These box cameras were the basis for the first photographic cameras in the early 1800s.

Early Discoveries of Light-Sensitive Materials

People have known for a very long time that light can change things. For example, sunlight can tan skin or fade clothes. People might have also thought about how to capture images seen in mirrors. However, there are no records of anyone thinking about photography before 1700. This is true even though people knew about light-sensitive materials and the camera obscura.

In 1614, Angelo Sala noticed that sunlight turned powdered silver nitrate black. He also saw that paper wrapped around silver nitrate for a year would turn black.

Wilhelm Homberg described how light darkened some chemicals in 1694.

First Attempts at Capturing Images (1700-1802)

Schulze's Fleeting Letter Pictures (around 1717)

Around 1717, a German scientist named Johann Heinrich Schulze accidentally found that a mix of chalk and nitric acid with some silver particles turned dark in sunlight. He experimented by placing stencils of words on a bottle filled with this mix. The stencils made copies of the text in dark red or violet colors on the white surface. These pictures lasted until the bottle was shaken or until all the contents were exposed to light. Schulze called his discovery "Scotophors" when he shared his findings in 1719. He thought it could help find silver in metals. Schulze's process was similar to later photogram techniques. Some people see it as the very first type of photography.

De la Roche's Fictional Image Capture (1760)

The early science fiction book Giphantie (1760) by Tiphaigne de la Roche described something like color photography. It talked about a process that fixed images made by light rays. The book said: "They coat a piece of canvas with this material, and place it in front of the object to capture. The first effect of this cloth is similar to that of a mirror... This impression of the image is instantaneous. The canvas is then removed and deposited in a dark place. An hour later the impression is dry, and you have a picture the more precious in that no art can imitate its truthfulness." De la Roche imagined a special material that worked with a mirror. The idea of drying the pictures in a dark place suggests he knew about light-sensitive materials.

Scheele's Forgotten Chemical Fixer (1777)

In 1777, chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele studied silver chloride, which is very sensitive to light. He found that light darkened it by breaking it down into tiny dark pieces of metallic silver. Even more useful, Scheele discovered that ammonia could dissolve the silver chloride but not the dark silver pieces. This discovery could have been used to make camera images permanent, or "fix" them. However, early photography experimenters didn't use this idea.

Scheele also noticed that red light didn't affect silver chloride much. This idea was later used in darkrooms. Red light allowed people to see black-and-white prints without ruining their development.

Wedgwood and Davy: Fleeting Detailed Photograms (1790s–1802)

English inventor Thomas Wedgwood is thought to be the first person to try making permanent pictures using a camera. He wanted to capture images from a camera obscura. But he found the images were too dim to affect the silver nitrate solution he used. Wedgwood did manage to copy painted glass plates and capture shadows on white leather and paper. He used paper wet with a silver nitrate solution. But he couldn't find a way to keep these pictures from fading.

It's not clear exactly when Wedgwood did these experiments. He might have started before 1790. In 1802, Humphry Davy published an article about Wedgwood's experiments. It was called An Account of a Method of Copying Paintings upon Glass, and of Making Profiles, by the Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver. Davy added that the method could copy things like leaves or insect wings. He also found that images from a solar microscope could be captured on prepared paper. Davy, perhaps forgetting Scheele's discovery, said that a way to make the pictures permanent was still needed. Wedgwood may have stopped his experiments because he was very sick. He died at age 34 in 1805.

Davy didn't continue the experiments. His article was read by many people, but it seemed to discourage them. They thought if a famous scientist like Davy couldn't find a way to fix images, it must be impossible.

Jacques Charles: Fleeting Silhouette Photograms (around 1801)

French inventor Jacques Charles is believed to have captured temporary negative pictures of silhouettes on light-sensitive paper. This was likely in the early 1800s, before Wedgwood's work was published. Charles died in 1823 without writing down his process. But he supposedly showed it in his lectures. It wasn't made public until François Arago mentioned it in 1839. Arago later said that Charles had the first idea of fixing camera images with chemicals.

Niépce's First Permanent Pictures (1816-1833)

In 1816, Nicéphore Niépce used paper coated with silver chloride. He managed to photograph images from a small camera. But these photos were negatives, meaning dark where the camera image was light. Also, they weren't permanent. Like earlier experimenters, Niépce couldn't stop the paper from turning completely dark when exposed to light for viewing. Disappointed with silver salts, he started looking at light-sensitive natural substances.

The oldest surviving photograph taken with a camera was made by Niépce in 1826 or 1827. He used a polished sheet of pewter. The light-sensitive material was a thin layer of bitumen, a natural tar. This bitumen was dissolved in lavender oil, spread on the pewter, and dried. After a very long exposure in the camera (thought to be eight hours, but maybe several days), the bitumen hardened where light hit it. The unhardened parts could then be washed away with a solvent. This left a positive image: light areas were hardened bitumen, and dark areas were bare pewter. To see the picture clearly, the plate had to be lit so the bare metal looked dark and the bitumen looked light.

Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône and Louis Daguerre in Paris worked together to improve the bitumen process. They used a more sensitive resin and a different way to treat the plate after exposure. This made better and easier-to-see images. Exposure times were still long, but much shorter than before.

Early Black-and-White Photography (1832-1840)

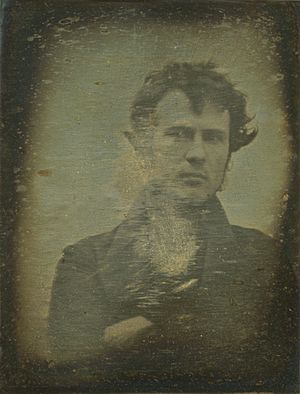

Niépce died suddenly in 1833, leaving his notes to Daguerre. Daguerre was more interested in silver-based methods. He experimented by photographing camera images directly onto a mirror-like silver plate. This plate was treated with iodine vapor, which reacted with the silver to form a layer of silver iodide. Like the bitumen process, the result looked positive when lit correctly. Exposure times were still too long until Daguerre made a key discovery. He found that a very faint, or "latent," image on the plate could be "developed" into a full picture using mercury fumes. This cut the exposure time to just a few minutes in good conditions. A strong, hot solution of common salt then "fixed" the image by removing the remaining silver iodide.

On January 7, 1839, this first complete practical photography process was announced. It happened at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences, and the news spread quickly. At first, all the details were kept secret. Pictures were only shown at Daguerre's studio to special guests. The French government bought the rights to the invention. They gave pensions to Niépce's son and Daguerre. Then, they shared the invention with the world as a free gift. The full instructions were made public on August 19, 1839. This process, called the daguerreotype, was the most common commercial method until the late 1850s. Then, the collodion process took its place.

Hércules Florence, born in France, developed his own photo technique in Brazil in 1832 or 1833. He used paper treated with silver nitrate to capture images. He couldn't properly fix his images. He stopped his project after hearing about the Daguerreotype in 1839. He reportedly called his technique "photographie" as early as 1833.

Henry Fox Talbot had already made stable photographic negatives on paper in 1835. But he worked to improve his process after hearing about Daguerre's invention. In early 1839, he got a key improvement from his friend John Herschel. Herschel, a scientist, had shown that "hypo" (now called sodium thiosulfate) could dissolve silver salts. This discovery also helped Daguerre, who soon used it instead of his original hot salt water method.

Talbot's early silver chloride experiments needed camera exposures of an hour or more. In 1841, Talbot invented the calotype process. Like Daguerre's method, it used chemical development of a faint image. This reduced exposure time to a few minutes. Paper with a silver iodide coating was exposed in the camera. It developed into a see-through negative image. Unlike a daguerreotype, which could only be copied by re-photographing it, a calotype negative could make many positive prints by simple contact printing. The calotype also looked softer than other early photos. This was good for portraits because it made faces look smoother. Talbot patented this process, which limited its use. He spent many years in lawsuits, trying to control his patent. But he was eventually defeated. Still, Talbot's negative process is the basic technology used by chemical film cameras today. Hippolyte Bayard also developed a photo method but announced it late, so he wasn't recognized as its inventor.

In 1839, John Herschel made the first glass negative. But his process was hard to repeat. Slovene Janez Puhar invented a way to make photos on glass in 1841. It was recognized in Paris in 1852. In 1847, Niépce's cousin, chemist Niépce St. Victor, published his invention of making glass plates with an albumen emulsion. Other inventors also created working negative-on-glass processes in the mid-1840s.

Photography in the Mid-to-Late 1800s

In 1851, English sculptor Frederick Scott Archer invented the collodion process. This process became very popular. Famous photographer and children's author Lewis Carroll used this process.

Herbert Bowyer Berkeley experimented with his own collodion emulsions. He found that adding sulfite to the pyrogallol developer worked well. In 1881, he shared his discovery. Berkeley's formula had pyrogallol, sulfite, and citric acid. Ammonia was added just before use to make it alkaline. This new formula was sold as Sulphur-Pyrogallol Developer.

Many photography processes in the 1800s were patented. Theodore Lilienthal, a photographer from New Orleans, successfully sued someone in 1881 for copying his "Lambert Process."

-

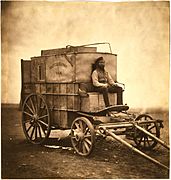

Roger Fenton's assistant on Fenton's photo van, Crimea, 1855

Photography Becomes Popular

The daguerreotype became very popular. This was because many middle-class people wanted portraits during the Industrial Revolution. Oil paintings were too expensive and slow to meet this demand. This helped push photography forward.

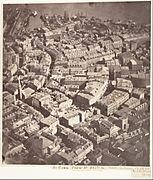

Roger Fenton and Philip Henry Delamotte helped make photography a popular way to record events. Fenton took pictures during the Crimean War. Delamotte recorded the taking apart and rebuilding of The Crystal Palace in London. Other photographers in the mid-1800s showed that photography was a more exact way to record landscapes and buildings than drawing. For example, Robert Macpherson's photos of Rome and the Vatican became a detailed visual record for tourists.

In 1839, François Arago announced the invention of photography. He showed the first photo taken in Egypt: a picture of Ras El Tin Palace.

In America, by 1851, a photographer named Augustus Washington advertised prices from 50 cents to $10 for daguerreotypes. However, daguerreotypes were fragile and hard to copy. Photographers wanted chemists to find ways to make many copies cheaply. This led them back to Talbot's process.

Over the first 20 years, photography improved a lot. In 1884, George Eastman from Rochester, New York, created dry gel on paper, or film. This replaced heavy photographic plates. Photographers no longer needed to carry boxes of plates and harmful chemicals. In July 1888, Eastman's Kodak camera went on sale with the slogan "You press the button, we do the rest." Now, anyone could take a photo and let others handle the difficult parts. Photography became available for everyone in 1901 with the Kodak Brownie.

-

General view of The Crystal Palace at Sydenham by Philip Henry Delamotte, 1854

-

An 1855 Punch cartoon. It made fun of problems with posing for Daguerreotypes.

-

The Market Square of Helsinki, in the 1890s

-

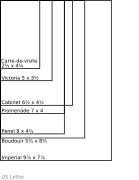

A comparison of common print sizes used in photo studios during the 19th century. Sizes are in inches.

Seeing in 3D: Stereoscopic Photography

Charles Wheatstone developed his mirror stereoscope around 1832. He showed his invention in June 1838. He quickly realized it could be combined with photography. He asked Henry Fox Talbot to make some calotype pairs for the stereoscope. He got the first results in October 1840. But he wasn't fully happy because the angle between the shots was too wide. Between 1841 and 1842, Henry Collen made calotypes of statues, buildings, and portraits. This included a portrait of Charles Babbage in August 1841. Wheatstone also got daguerreotype stereograms from other photographers in 1841 and 1842.

David Brewster developed a stereoscope with lenses and a special camera in 1844. He showed two stereoscopic self-portraits made by John Adamson in March 1849. A stereoscopic portrait of Adamson, dated "circa 1845," might be one of these. A stereoscopic daguerreotype portrait of Michael Faraday, dated "circa 1848," might be even older.

The Invention of Color Photography

People wanted a way to take color photos from the very beginning. Edmond Becquerel showed results as early as 1848. But his exposures took hours or days. Also, the colors were so sensitive to light that they could only be looked at briefly in dim light.

The first lasting color photograph was actually three black-and-white photos. They were taken through red, green, and blue color filters. Then, they were shown together using three projectors with similar filters. Thomas Sutton took this photo in 1861 for a lecture by Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell. Maxwell had suggested this method in 1855. The photo materials used then weren't sensitive to most colors, so the result wasn't perfect. This demonstration was soon forgotten. Maxwell's method is now best known through the work of Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii in the early 1900s. It became practical after Hermann Wilhelm Vogel discovered a way to make emulsions sensitive to more colors in 1873. This was slowly introduced into use starting in the mid-1880s.

Two French inventors, Louis Ducos du Hauron and Charles Cros, worked separately in the 1860s. They famously revealed their similar ideas on the same day in 1869. Their ideas included ways to view three color-filtered black-and-white photos in color without projecting them. They also found ways to make full-color prints on paper.

The first widely used color photography method was the Autochrome plate. Inventors and brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière started working on it in the 1890s. They sold it in 1907. It was based on one of Louis Duclos du Haroun's ideas. Instead of taking three separate photos through color filters, you took one through a mosaic of tiny color filters on the photo material. Then, you viewed the results through a similar mosaic. If the filter parts were small enough, the three main colors (red, blue, and green) would blend in your eye. This would create the same color mix as projecting three separate photos.

Autochrome plates had a built-in mosaic filter layer. It had about five million tiny, dyed potato grains per square inch. These grains were flattened with five tons of pressure. This allowed each grain to capture and absorb color. Their tiny size created the illusion that the colors merged. The last step was adding a layer of silver bromide, which captures light. After this, a color image could be made and developed. To see it, a special process called reversal processing was used. This turned each plate into a clear positive that could be viewed or projected. One problem was that it needed at least a second of exposure in bright daylight. In poor light, it took much longer. An indoor portrait needed several minutes, with the person staying still. This was because the grains absorbed color slowly. Also, a yellowish-orange filter was needed to keep the photo from looking too blue. This filter, though necessary, reduced the light absorbed. Another problem was that the image couldn't be enlarged too much. If it was, the many dots that made up the image would become visible.

Other similar products soon appeared. Film versions were also made. All were expensive. Until the 1930s, none were fast enough for quick snapshots. So, they were mostly used by wealthy hobbyists.

A new age in color photography began with Kodachrome film. It was available for 16 mm home movies in 1935 and 35 mm slides in 1936. It captured red, green, and blue colors in three layers of material. A complex process then created complementary cyan, magenta, and yellow dye images in those layers. This resulted in a subtractive color image. Maxwell's method of taking three separate filtered black-and-white photos was still used for special purposes into the 1950s. Polachrome, an "instant" slide film that used the Autochrome's idea, was available until 2003. But the few color print and slide films made today all use the multi-layer approach first used by Kodachrome.

-

The first lasting color photograph, taken by Thomas Sutton in 1861.

-

An 1877 color photo print on paper by Louis Ducos du Hauron, an early French pioneer of color photography.

-

Albert Bierstadt photographed by his brother Edward Bierstadt. This may be the oldest surviving color portrait photo.

-

Color photograph of Saas-Fee by Gabriel Lippmann, 1891-99.

-

Alim Khan photographed by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky using Maxwell's method, 1911

-

A color portrait of Mark Twain by Alvin Langdon Coburn, 1908, made with the new Autochrome process.

-

Kodachrome photo by Chalmers Butterfield of Shaftesbury Avenue from Piccadilly Circus, in London, around 1949.

How Digital Photography Developed

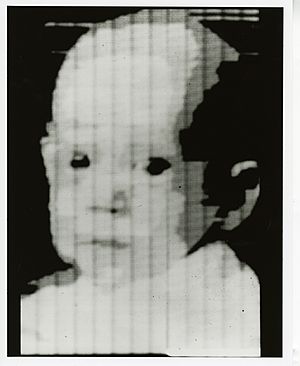

In 1957, a team led by Russell A. Kirsch at the National Institute of Standards and Technology created a binary digital version of an existing technology. This was a wirephoto drum scanner. It allowed letters, diagrams, photos, and other graphics to be put into digital computer memory. One of the first photos scanned was a picture of Kirsch's baby son Walden. The picture was 176x176 pixels. It had only one bit per pixel, meaning it was stark black and white with no gray tones. But by combining many scans of the photo with different black-white settings, grayscale information could also be captured.

The charge-coupled device (CCD) is the part that captures images in early digital cameras. It was invented in 1969 by Willard Boyle and George E. Smith at AT&T Bell Labs. They were working on memory devices. The lab was also working on the Picturephone and developing semiconductor bubble memory. By combining these ideas, Boyle and Smith designed what they called "Charge 'Bubble' Devices." The main idea was to move electrical charge along the surface of a semiconductor. However, Dr. Michael Tompsett from Bell Labs discovered that the CCD could be used as an imaging sensor. The CCD has increasingly been replaced by the active pixel sensor (APS). These are commonly used in cell phone cameras. Billions of people worldwide use these mobile phone cameras. This has greatly increased photo taking and sharing. It also helps with citizen journalism.

- 1973 – Fairchild Semiconductor releases the first large image-capturing CCD chip: 100 rows and 100 columns.

- 1975 – Bryce Bayer of Kodak develops the Bayer filter mosaic pattern for CCD color image sensors.

- 1986 – Kodak scientists develop the world's first megapixel sensor.

The web has been a popular place for storing and sharing photos. The first photo was put on the web by Tim Berners-Lee in 1992. It was an image of the CERN house band Les Horribles Cernettes. Since then, sites and apps like Facebook, Flickr, Instagram, Picasa (closed in 2016), Imgur, Photobucket, and Snapchat have been used by millions of people to share their pictures.

Gallery of Historical Photos

-

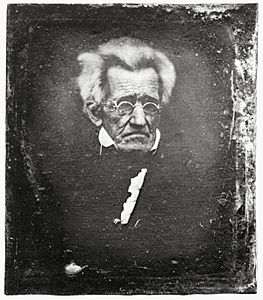

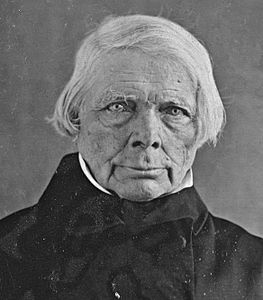

Andrew Jackson at age 78.

-

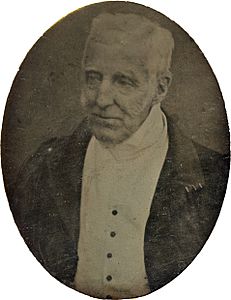

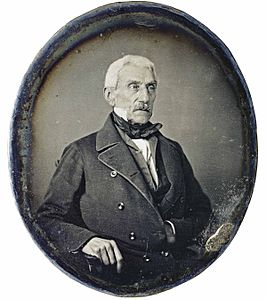

Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, aged 74 or 75, made by Antoine Claudet in 1844.

-

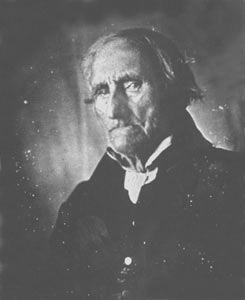

Philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, made by Hermann Biow in February 1848.

-

José de San Martín, made in Paris 1848.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la fotografía para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la fotografía para niños

- History of the camera

- History of Photography (academic journal)

- Albumen print

- History of photographic lens design

- Timeline of photography technology

- Outline of photography

- List of photographs considered the most important

- Photography by indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Women photographers

- Movie camera

- Instant film

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |