History of Poland in the early modern period (1569–1795) facts for kids

The early modern era of Polish history is a time that came after the Middle Ages. Historians usually say this period started around 1500 AD and lasted until about 1800.

In 1505, a special law called Nihil novi was passed by the Polish parliament, known as the diet. This law took power away from the king and gave it to the diet. This moment began a time called the "Nobles' Democracy" or "Nobles' Commonwealth." During this era, the country was mostly ruled by the "free and equal" Polish nobles, called szlachta. They often competed with the Jagiellon kings and later, kings who were chosen by election.

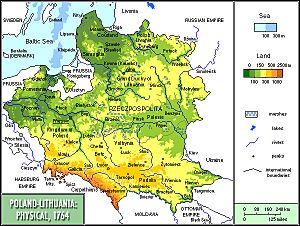

In 1569, the Union of Lublin created the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. This was a closer joining of the Crown of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which were already linked. The start of the Commonwealth was a time when Poland grew very large and powerful. It became an important player in Europe and helped spread Western culture to the east.

After the Reformation, there was a lot of religious freedom. But then the Catholic Church started a movement called the Counter-Reformation. This brought many people back to Catholicism from Protestant faiths. There were also problems with the eastern Ruthenian people in the Commonwealth. An attempt to solve this was made with the religious Union of Brest. On the military side, there were several Cossack uprisings.

The Commonwealth was strong militarily under King Stephen Báthory. But it faced problems with its rulers during the reigns of the Vasa kings Sigismund III and Władysław IV. The country also had internal fights between kings, powerful nobles (magnates), and different groups of nobility. The Commonwealth fought wars with Russia, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire.

However, things soon got much worse. From 1648, the Cossack Khmelnytsky Uprising spread across the south and east. This was quickly followed by a Swedish invasion that swept through Poland. Wars with the Cossacks and Russia left Ukraine divided. The eastern part was lost by the Commonwealth and became part of the Tsardom. John III Sobieski fought long wars with the Ottoman Empire. He helped Poland become strong again, and in 1683, he famously helped save Vienna from a Turkish attack.

The Commonwealth faced almost constant warfare until 1720. It lost many people and its economy and society were badly damaged. The government became weak because of big internal conflicts. For example, the Lubomirski's Rokosz against John II Casimir and other noble groups. Laws were also corrupted by the liberum veto system, and foreign countries started to control things. The "ruling" noble class fell under the control of a few very powerful families. The reigns of two kings from the Saxon Wettin dynasty, Augustus II and Augustus III, led to even more problems for the Commonwealth.

The Polish-Lithuanian state was controlled by the Russian Empire from the time of Peter the Great. This foreign control became strongest under Catherine the Great. At this time, the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Habsburg monarchy were also involved. In the late 1700s, the Commonwealth's economy got better, its culture grew, and it tried to make big changes inside the country. These reforms made the neighboring powers angry, and they responded with military action. The royal election of 1764 brought Stanisław August Poniatowski to the throne.

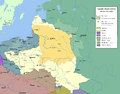

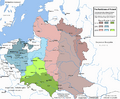

The Bar Confederation of 1768 was a rebellion by the nobles against Russia and the Polish king. It was put down, and in 1772, the First Partition of the Commonwealth happened. This meant Russia, Prussia, and Austria permanently took parts of the Commonwealth's outer lands.

The Great, or Four-Year Sejm was called by Stanisław August in 1788. Its most important achievement was passing the Constitution of May 3, 1791. This is seen as the first modern constitution in Europe. This constitutional reform caused strong opposition from conservative nobles in the Commonwealth and from Catherine II of Russia.

The nobles' Targowica Confederation asked Empress Catherine for help. In May 1792, the Russian army entered the Commonwealth. The defensive war fought by the Commonwealth ended when the King gave up. He believed resistance was useless and joined the Targowica Confederation. In 1793, Russia and Prussia arranged and carried out the Second Partition of the Commonwealth. This left the country with much less land and almost unable to exist on its own.

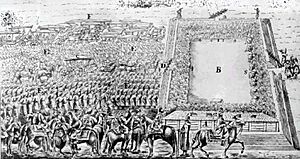

Reformers and patriots soon prepared for a national uprising. Tadeusz Kościuszko, a military leader, was chosen to lead it. On March 24, 1794, in Cracow (Kraków), he declared a national uprising. Kościuszko freed many peasants and let them join his army. But the hard-fought uprising was crushed by the forces of Russia and Prussia. The third and final partition of the Commonwealth was done again by all three powers. In 1795, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth stopped existing.

Contents

Electing New Kings

How Kings Were Chosen

When Sigismund II Augustus died in 1572, it ended almost 200 years of rule by the Jagiellon dynasty in Poland. For three years, there was no king. During this time, the Polish nobles (szlachta) worked out how to choose a new ruler. Even lower-ranking nobles were now part of the selection process. The king's power was further limited, giving more power to the growing noble class. They wanted to make sure they would stay in charge.

Each new king had to sign two important documents. One was the Henrician Articles, named after Henry of Valois, the first king after the Jagiellons. These were the basic rules of Poland's political system. The other was the pacta conventa, which were special promises the chosen king had to make. From then on, the king was like a partner with the nobility. He was a top member of the parliament (sejm) and was always watched by a group of high-ranking nobles, called senators.

Having kings who were chosen, instead of kings who inherited the throne, made the government less stable. With each election, the nobles who voted wanted more power for themselves and less for the king. This led to a constant power struggle. Powerful nobles (magnates) and lesser nobles also caused problems with their constant arguments. This made the government weaker. Eventually, foreign countries took advantage of this weakness. They started to control who became king and how Poland-Lithuania was run.

When it was time to choose a new king, the nobles often preferred foreign candidates. They hoped these kings would not start another powerful family line. But this often led to kings who were not effective or who constantly fought with the nobility. Foreign kings were often new to Poland's ways. They were also busy with their own countries' politics. They sometimes put their own country's interests before Poland's.

Henry of Valois (1573–1574)

In April 1573, Sigismund's sister Anna was the only heir to the throne. She convinced the Sejm to choose the French prince Henry of Valois as king. Henry's marriage to Anna was meant to make his rule more legitimate. But less than a year after he was crowned, Henry left Poland. He went back to France to become King after his brother Charles IX died.

Stephen Báthory (1576–1586)

Transylvanian Stephen Báthory (1576–1586) was a skilled and strong king. He was good at military matters and at ruling the country. He is considered one of the best elected kings.

During the Livonian War (1558–1582), Poland-Lithuania fought against Ivan the Terrible of Russia. Polish forces besieged the city of Pskov. The city was not captured, but Báthory, with his Chancellor Jan Zamoyski, led the Polish army to a big victory. They forced Russia to give back lands it had taken. Poland gained Livonia and Polotsk. In 1582, the war ended with the Truce of Jam Zapolski.

The Commonwealth's armies got back most of the lost areas. By the end of Báthory's reign, Poland controlled two main ports on the Baltic Sea: Danzig (Gdańsk) and Riga. Danzig controlled trade on the Vistula River, and Riga controlled trade on the Daugava River. Both cities were among the largest in the country.

Stephen Báthory wanted to create a Christian alliance against the Islamic Ottomans. He thought an alliance with Russia was needed for his plan. But Russia was heading into a difficult time called the Time of Troubles, so he couldn't find a partner there. When Báthory died, there was another year without a king. Emperor Mathias' brother, Archduke Maximilian III, tried to claim the Polish throne. But he was defeated at Byczyna during the War of the Polish Succession (1587–1588). Sigismund III Vasa became the next king. He was the first of three rulers from the Swedish House of Vasa.

Vasa Kings Rule Poland

Sigismund III Vasa (1587–1632)

Sigismund III Vasa was King of Poland from 1587 to 1632. He was also King of Sweden from 1592 to 1599. He was the son of John III Vasa of Sweden and Catherine, who was the daughter of Sigismund I the Old of Poland. Polish nobles were annoyed because he dressed in Spanish and other Western European styles. Sigismund III was a very strong Catholic. He wanted to win the Swedish crown and bring Sweden back to Catholicism. Because of this, Sigismund III got Poland involved in unnecessary and unpopular wars with Sweden. During these wars, the parliament refused to give him money and soldiers. Sweden then took Livonia and Prussia.

For the first few years of Sigismund's reign (until 1598), Poland and Sweden were joined under one ruler. This made the Baltic Sea like an internal lake. However, a rebellion in Sweden started a long period of wars with Sweden that lasted over a century.

The Catholic Church began a strong effort to win people back, called the Counter-Reformation. Many Protestants became Catholics. The Union of Brest caused a split among the Eastern Christians in the Commonwealth. To promote Catholicism, the Uniate Church was created at the Synod of Brest in 1596. This church accepted the Pope's authority but followed Eastern rituals. Many people in the Commonwealth's eastern lands left the Orthodox Church to join the Uniates.

Sigismund tried to bring in absolutism, a system where the king has total power, like in other parts of Europe. He also wanted to get his old Swedish throne back. This led to a rebellion by the szlachta (nobility). In 1607, the Polish nobles threatened to stop their agreements with the king, but they did not try to overthrow him.

For ten years, between 1619 and 1629, the Commonwealth was at its largest size ever. In 1619, the Russo-Polish Truce of Deulino took effect. Russia gave up control of Smolensk and other border areas to the Commonwealth. In 1629, the Swedish-Polish Truce of Altmark happened. The Commonwealth gave most of Livonia to Sweden, which the Swedes had invaded in 1626.

Sigismund III Vasa did not manage to make the Commonwealth stronger or solve its internal problems. He focused on trying to get his Swedish throne back, which was unsuccessful.

Wars with Sweden and Russia

Sigismund's wish to get the Swedish throne back led him into long wars against Sweden and later also Russia. In 1598, Sigismund tried to defeat Charles IX of Sweden with an army from both Sweden and Poland. But he was defeated in the Battle of Stångebro.

When the Tsardom of Russia went through its "Time of Troubles," Poland did not fully take advantage of the situation. Military campaigns sometimes brought Poland close to conquering Russia and the Baltic coast. But the ongoing wars with the Ottoman Empire and Sweden prevented this from happening. After a long war with Russia, Polish forces occupied Moscow in 1610. The position of tsar, which was empty in Russia, was offered to Sigismund's son, Władysław. However, Sigismund did not want his son to become tsar. He hoped to get the Russian throne for himself. Two years later, the Poles were driven out of Moscow. Poland lost a chance for a Polish-Russian union.

Poland avoided the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), which destroyed much of Western Europe, especially Prussia. In 1618, the Elector of Brandenburg became the ruler of the Duchy of Prussia on the Baltic coast. From then on, Poland's link to the Baltic Sea was surrounded by two parts of the same German state.

Wars in the South

The Commonwealth saw itself as the "protector of Christendom" against the Ottoman Empire's plans to conquer Europe. From the second half of the 16th century, relations between Poland and the Ottomans got worse. This was due to increasing border fights between Cossacks and Tatars. This turned the entire border region into a constant warzone. A constant threat from the Crimean Tatars led to the rise of Cossackdom.

In 1595, powerful nobles (magnates) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth got involved in the affairs of Moldavia. This started a series of conflicts that spread to Transylvania, Wallachia, and Hungary. The Polish magnates' forces clashed with forces supported by the Ottoman Empire and sometimes the Habsburgs. Everyone was competing for control over that region.

The Commonwealth was fighting almost constantly on its northern and eastern borders with Sweden and Russia. This meant its armies were spread thin. The wars in the south ended with a Polish defeat at the Battle of Cecora in 1620. The Commonwealth had to give up all its claims to Moldavia, Transylvania, Wallachia, and Hungary.

Religious and Social Issues

The people in Poland-Lithuania were not all Roman Catholic or Polish. This was because of the union with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In Lithuania, East Slavic Ruthenian people were the majority. During the "Republic of Nobles" era, being "Polish" was more about social rank than ethnicity. It mostly meant being a landed noble, whether you were of Polish origin or not. Generally, non-Polish noble families in Lithuania slowly adopted the Polish language and culture.

Because of this, in the eastern parts of the Kingdom, Polish-speaking nobles owned most of the land. But the peasants, who were the majority, were usually not Polish or Catholic. Also, decades of peace led to many people settling in Ukraine. This increased tensions between peasants, Jews, and nobles. The tensions got worse because of conflicts between the Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches after the Union of Brest. There were also several Cossack uprisings. In the west and north of the country, cities had many German people, who were often Protestant. In 1672, the Tatar subjects rebelled against the Commonwealth in the Lipka Rebellion.

Władysław IV Vasa (1632–1648)

During the reign of Sigismund's son, Władysław IV Vasa, the Cossacks in Ukraine revolted against Poland. Wars with Russia and Turkey weakened the country. The nobles (szlachta) gained new special rights, mainly being free from income tax.

Władysław IV wanted to achieve many military goals. These included conquering parts of Russia, Sweden, and Turkey. His reign had many small victories, but few brought lasting benefits to the Commonwealth. He was once chosen as a Russian tsar, but he never controlled Russian lands. Like his father, Władysław was involved in Swedish family ambitions. He failed to make the Commonwealth stronger or prevent the terrible events of the Khmelnytsky Uprising and the Deluge. These events devastated the Commonwealth from 1648 onwards.

John Casimir Vasa (1648–1668)

The reign of Władysław's brother, John Casimir, was the last of the Vasa kings. It was dominated by the peak of the war with Sweden. The two previous Vasa kings had set the stage for this conflict. In 1660, John Casimir had to give up his claims to the Swedish throne. He also had to accept Swedish control over Livonia and the city of Riga.

Under John Casimir, the Cossacks became more powerful. The Cossacks were sometimes able to defeat the Poles. The Swedes occupied much of Poland, including Warsaw, the capital. The King, abandoned by his people, had to temporarily hide in Silesia. As a result of the wars with the Cossacks and Russia, the Commonwealth lost Kiev, Smolensk, and all the areas east of the Dnieper River. This happened with the Treaty of Andrusovo in 1667. During John Casimir's reign, East Prussia officially stopped being a fief (land held under a lord) of Poland. Inside the country, things started to fall apart. Nobles made their own alliances with foreign powers and followed their own policies. The rebellion of Jerzy Lubomirski shook the king's power.

John Casimir was a broken and disappointed man. He gave up the Polish throne on September 16, 1668. This happened amid internal chaos and fighting. He returned to France, where he joined the Jesuit order and became a monk. He died in 1672.

Khmelnytsky Uprising (1648–1654)

The Khmelnytsky Uprising was the largest of the Cossack uprisings. It was terrible for the Commonwealth. The Cossacks, allied with the Tatars, defeated the Commonwealth's forces in several battles. The Commonwealth did win a big victory at Berestechko. But the Polish-Lithuanian state was "fatally wounded." The easternmost parts of its land were lost to Russia. This led to a long-term shift in who held power. In the short term, the country was weakened just as Sweden invaded.

The Deluge (1648–1667)

Even though Poland-Lithuania was not affected by the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), the next two decades brought one of its worst times ever. This difficult period became known as potop, or the Deluge. It was named for how sudden and huge the problems were. The crisis began when the Ukrainian Cossacks revolted. They declared an independent state near Kiev. They allied with the Crimean Tatars and the Ottoman Empire. Their leader, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, defeated Polish armies in 1648 and 1652. After the Cossacks made the Treaty of Pereyaslav with Russia in 1654, Tsar Alexis took over the entire eastern part of the Commonwealth (Ukraine) up to Lwów (Lviv).

Taking advantage of Poland's problems in the east, Charles X Gustav of Sweden intervened. Most of the Polish nobility and the Polish vassal Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia agreed to recognize him as king. He promised to drive out the Russians. However, the Swedish troops looted and destroyed the area. This caused the Polish people to revolt. The Swedes took over the rest of Poland, except for Lwów and Danzig (Gdańsk).

Poland-Lithuania fought back and got most of its lost lands from the Swedes. In return for breaking his alliance with Sweden, Frederick William, the ruler of Ducal Prussia, became an independent ruler. Much of the Polish Protestant nobility had sided with the Swedes. Under Hetman Stefan Czarniecki, the Poles and Lithuanians drove the Swedes out of the Commonwealth by 1657. Frederick William's armies also intervened but were defeated. Frederick William's rule over East Prussia was recognized, though Poland kept the right to inherit it until 1773.

The thirteen-year struggle over control of Ukraine included an attempted formal union of Ukraine with the Commonwealth as an equal partner (1658). Poland also had military successes in 1660–1662. But this was not enough to keep eastern Ukraine. Because of ongoing Ukrainian unrest and the threat of a Turkish-Tatar intervention, the Commonwealth and Russia signed an agreement in 1667. This agreement stated that eastern Ukraine (the left bank of the Dnieper River) now belonged to Russia. Kiev was also given to Russia for two years, but it was never returned. Eventually, Poland accepted Russian control of the city.

The potop wars caused huge damage and greatly contributed to the country's eventual downfall. John Casimir was blamed for the biggest disaster in Polish history and gave up his throne in 1668. The Commonwealth's population was reduced by a shocking one-third. This was due to war deaths, slave raids, plagues, and mass killings of civilians. Most Polish cities were destroyed, and the nation's economy was ruined. The war was paid for by printing worthless money, which caused huge inflation. Religious feelings also became stronger due to the conflict, ending the tolerance of non-Catholic beliefs. From then on, the Commonwealth would be on the defensive against hostile and increasingly powerful neighbors.

Commonwealth After the Deluge

In the Treaty of Oliva in 1660, John Casimir finally gave up his claims to the Swedish crown. This ended the long conflict between Sweden and the Commonwealth and the series of wars between them.

After the Truce of Andrusovo of 1667 and the Eternal Peace Treaty of 1686, the Commonwealth lost left-bank Ukraine to Russia.

Polish culture and the Uniate East Slavic Greek Catholic Church slowly grew. By the 18th century, the populations of Ducal Prussia and Royal Prussia were a mix of Catholics and Protestants. They spoke both German and Polish. The rest of Poland and most of Lithuania remained mostly Roman Catholic. Ukraine and some parts of Lithuania (Belarus) were Greek Orthodox and Greek Catholic. Society included nobles (8%), clergy (1%), townspeople, and mostly peasants. There were many different groups of people, including Poles, Germans, Jews, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Armenians, and Tatars.

Polish Kings and Ottoman Wars

Michael Korybut Wiśniowiecki (1669–1673)

After King John Casimir Vasa gave up his throne and the Deluge ended, the Polish nobles (szlachta) were unhappy with the Vasa dynasty kings. They chose Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki as king. They believed that as a Pole, he would better serve the Commonwealth's interests. He was the first Polish-born ruler since Sigismund II Augustus died in 1572. Michael was the son of Jeremi Wiśniowiecki, a military commander popular with the nobles.

His reign was not successful. Michael lost a war against the Ottoman Empire. The Turks occupied Podolia and most of Ukraine from 1672 to 1673. Wiśniowiecki was a weak king who was easily influenced by the Habsburgs. He could not handle his duties or the fighting groups within Poland.

John III Sobieski (1674–1696)

Hetman John Sobieski was the Commonwealth's last great military leader. He was active and effective in the ongoing wars with the Ottoman Empire. Sobieski was elected as another "Piast" king, meaning he was from a Polish family. John III's most famous achievement was his decisive help in defeating the Ottoman Empire's army in 1683, at the Battle of Vienna.

If the Ottomans had won, they likely would have threatened Western Europe. But the successful battle stopped that possibility. It marked a turning point in the 250-year struggle between Christian Europe and the Islamic Ottoman Empire. Over the next 16 years (the Great Turkish War), the Turks were permanently pushed south of the Danube River. They never threatened Central Europe again.

For the Commonwealth, there was no big reward for these victories against the Turks. The rescuer of Vienna had to give up lands to Russia. This was in return for promised help against the Crimean Tatars and Turks. Poland had already officially given up all claims to Kiev in 1686. On other fronts, John III was less successful. This included agreements with France and Sweden in a failed attempt to get back the Duchy of Prussia. Only when the Holy League made peace with the Ottomans in 1699, did Poland get back Podolia and parts of Ukraine.

Commonwealth's Decline

Starting in the 17th century, the nobles' democracy slowly turned into anarchy. This was due to worsening internal politics and destructive wars. The once powerful Commonwealth became easy for foreign countries to interfere with. By the late 17th century, Poland-Lithuania had almost stopped working as a truly independent state.

During the 18th century, the Polish-Lithuanian federation was controlled by Sweden, Russia, the Kingdom of Prussia, France, and Austria. Poland's weakness was made worse by a parliament that did not work well. Each deputy in the sejm could use his vetoing power to stop all further parliamentary work for that session. This greatly weakened Poland's central government and led to its destruction.

The decline that led to foreign control began seriously decades after the end of the Jagiellon dynasty. Not enough taxes were collected, and nobles (szlachta) strongly opposed any taxes that affected their interests. This also contributed to the downfall. There were two types of taxes: those collected by the Crown and those by local assemblies. The Crown collected customs duties and taxes on land, transport, salt, lead, and silver. The Sejm collected a land tax, a city tax, an alcohol tax, and a poll tax on Jews. Nobles did not pay taxes on their exports and imports. The disorganized way taxes were collected and the many exceptions meant the king and state did not have enough money for military or civilian needs. At one point, the king secretly and illegally sold crown jewels.

The nobles, or szlachta, became more focused on protecting their own "liberties." They blocked any policies meant to strengthen the nation or build a strong army. Starting in 1652, the harmful practice of liberum veto was their main tool. It required everyone in the sejm to agree. A single deputy could not only block any measure but also cause the entire sejm session to end. All measures already passed would have to wait for the next sejm. Foreign diplomats often used bribes or persuasion to cause inconvenient sejm sessions to be dissolved. Out of 37 sejms between 1674 and 1696, only 12 were able to pass any laws. The others were dissolved by the liberum veto of one person or another.

The Commonwealth's last military victory happened in 1683. King John III Sobieski drove the Turks away from Vienna with a powerful cavalry charge. Poland's important role in helping the European alliance push back the Ottoman Empire was rewarded with some land in Podolia by the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699). This partial success did little to hide the internal weakness and paralysis of Poland-Lithuania's political system.

For the next 25 years, Poland was often used by Russia in its campaigns against other powers. When John III died in 1697, 18 candidates wanted the throne. It eventually went to Frederick Augustus of Saxony, who then became Catholic. Ruling as Augustus II, his reign offered a chance to unite Saxony (an industrial area) with Poland, a country rich in resources. However, the King was not skilled in foreign policy. He got involved in a war with Sweden. His allies, the Russians and Danes, were pushed back by Charles XII of Sweden. This started the Great Northern War. Charles put a puppet ruler in Poland and marched on Saxony. He forced Augustus to give up his crown and turned Poland into a base for the Swedish army. Poland was again destroyed by the armies of Sweden, Russia, and Saxony. Its major cities were ruined, and one-third of the population died from the war and a plague outbreak in 1702-13. The Swedes finally left Poland and invaded Ukraine, where they were defeated by the Russians at Poltava. Augustus was able to get his throne back with Russian support. But Tsar Peter the Great decided to take Livonia in 1710. He also put down the Cossacks, who had been rebelling against Poland since 1699. Later, the Tsar stopped Prussia from gaining land from Poland, even though Augustus approved it. After the Great Northern War, Poland became a protectorate of Russia for the rest of the 18th century. The widespread European War of the Polish Succession, named after the conflict over who would succeed Augustus II, was fought from 1733–1735.

In the 18th century, the king's and central government's powers became mostly just on paper. Kings were not allowed to provide for basic defense or finances. Powerful aristocratic families made treaties directly with foreign rulers. Attempts to reform were stopped by the nobles' determination to keep their "golden freedoms," especially the liberum veto. Because of the chaos caused by the veto, under Augustus III (1733–63), only one of thirteen sejm sessions ended in an orderly way.

Unlike Spain and Sweden, which were great powers that peacefully became less important, Poland faced its decline at a key crossroads of the continent. Without strong central leadership and powerless in foreign relations, Poland-Lithuania became a tool for the ambitious kingdoms around it. It was a huge but weak buffer state. During the reign of Peter the Great (1682–1725), the Commonwealth fell under Russia's control. By the mid-18th century, Poland-Lithuania was practically a protectorate of its eastern neighbor. It kept only a theoretical right to rule itself.

By the 18th century, people outside Poland often made fun of how ineffective the sejms were. They blamed the liberum veto. Across Europe, political thinkers all agreed it was a terrible failure. Many Polish nobles saw the veto as a useful tool. They used it as a weapon against what they saw as the king's attempts to gain too much power. The long-term result was a weak state that could not compete with its neighbors, especially Prussia and Russia. Poland was eventually divided among them, and the nobles lost all their political rights and their country.

Several decades before Poland lost its independence, thinkers began to rethink the role of the veto and the meaning of Polish liberty. They argued that Poland had not progressed as fast as the rest of Europe because it lacked political stability. Exposure to Enlightenment ideas gave Poles more reasons to reconsider ideas like society and equality. This led to the idea of the naród, or nation. This was a nation where all people, not just the nobility, should have political freedom. The reform movement came too late to save the state. But it helped form a strong nation that could survive the long period of Partitioned Poland.

Polish-Saxon Kings

After John III Sobieski's death, the Polish-Lithuanian throne was held for seven decades by the German Prince-elector of Saxony, Augustus II the Strong, and his son, Augustus III. They were from the House of Wettin.

Augustus II the Strong (1697–1706, 1709–1733)

Augustus II the Strong, also known as Frederick Augustus I, was a very ambitious ruler. In the race for the Polish throne, he defeated his main rival, François Louis, Prince of Conti, who was supported by France. He also defeated King John III's son, Jakub. To make sure he became the Polish king, he changed from Lutheranism to Roman Catholicism. Augustus II practically bought the election. Augustus hoped to make the Polish throne hereditary for his family, the House of Wettin. He also wanted to use his power as Elector of Saxony to bring order to the chaotic Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. However, he soon got sidetracked from his reform plans. He became focused on the possibility of conquering other lands.

In alliance with Peter the Great of Russia, Augustus won back Podolia and western Ukraine. He ended the long series of Polish-Turkish wars with the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699). A Cossack revolt that began in 1699 was put down by the Russians. Augustus tried unsuccessfully to get the Baltic coast back from Charles XII of Sweden. He allied with Denmark and Russia, starting a war with Sweden. After Augustus' allies were defeated, Sweden's king Charles XII marched from Livonia into Poland. He then used Poland as his base. He put a puppet ruler (King Stanisław Leszczyński) in Warsaw. He occupied Saxony and drove Augustus II from the throne. Augustus was forced to give up the crown from 1704 to 1709. But he got it back when Tsar Peter defeated Charles XII at the Battle of Poltava (1709).

Poland had only recently recovered its population to 1650 levels after suffering huge war damages. Now, it was completely destroyed again by the armies of Sweden, Saxony, and Russia. Two million people died from the war and disease epidemics. Cities were ruined, and cultural losses were immense. After the Swedish defeat, Augustus II regained the throne with Russian support. But the Russians then took Livonia after driving the Swedes out.

Augustus II was helpless when, in 1701, the Elector of Brandenburg declared himself sovereign "King in Prussia," as Frederick I. This created the aggressive, militaristic Prussian state, which would later form the core of a united Germany. The winner of Poltava, Tsar Peter the Great, declared Russia to be the protector of the Polish-Lithuanian Republic's borders. This meant the Commonwealth became a Russian protectorate. It stayed in this condition until it ceased to exist in 1795. Russia's policy was to control Poland politically in cooperation with Austria and Prussia.

Stanisław Leszczyński (1706–1709, 1733–1736)

Stanisław Leszczyński was seen as a puppet of Sweden during his first time on the throne. He ruled during a time of chaos. Augustus II soon got the throne back, forcing him into exile. He was elected king again after Augustus died in 1733, with support from France and Polish nobles. But Poland's neighbors did not support him. After military action by Russian and Saxon troops, he was besieged in Danzig (Gdańsk). He was again forced to leave the country. For the rest of his life, Leszczyński became a successful and popular ruler in the Duchy of Lorraine.

August III (1733–1763)

Augustus III was also Elector of Saxony (as Frederick Augustus II). He inherited Saxony after his father's death. He was elected King of Poland by a minority of the sejm with the support of Russian troops. Augustus III was controlled by Russia. During his reign, foreign armies crossed the land many times. He was not interested in the affairs of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He saw it mostly as a way to get money and resources to strengthen his power in Saxony. During his 30-year reign, he spent less than 3 years in Poland. He gave most of his powers to Count Heinrich von Brühl. Augustus III's lack of involvement led to political chaos and further weakened the Commonwealth. Meanwhile, neighboring Prussia, Austria, and especially Russia became more and more powerful in its affairs.

Reforms and Partitions Under Stanisław August Poniatowski (1764–1795)

From the early years of Empress Catherine the Great's reign (1762–1796), Russia increased its control over Polish affairs. Prussia and Austria, the other powerful countries around Poland, also took advantage of internal religious and political arguments. The neighboring states divided up the country in three stages. The third one in 1795 removed Poland-Lithuania from the map of Europe.

-

Second Partition of Poland (1793)

Russian Control and First Partition

More educated Poles now realized that reforms were needed. One group, led by the Czartoryski family, wanted to get rid of the harmful liberum veto. They promoted a wide plan for reform. Their main rivals were the Potocki family. The Czartoryskis worked with the Russians. In 1764, Empress Catherine II of Russia forced the election of a member of the Czartoryski family, her former favorite, Stanisław August Poniatowski, as king of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He surprised some by encouraging changes to his country's broken political system. He also achieved a temporary stop to the use of the liberum veto in the sejm (1764–1766). This threatened to make the central government stronger. This made foreign capitals unhappy, as they preferred a weak, easily controlled Poland. Catherine, displeased, encouraged religious disagreements among Poland-Lithuania's large Eastern Orthodox population. These people had lost rights that were guaranteed to them in the 16th century.

Under strong Russian pressure, the unhappy sejm introduced religious tolerance. Orthodox and Protestant people were given equal rights with Catholics in 1767. Through the Polish nobles that Russia controlled (the Confederation of Radom) and Russian Minister to Warsaw Prince Nicholas Repnin, Catherine forced a sejm constitution (a set of laws). This undid Poniatowski's reforms of 1764. The liberum veto and other old abuses of noble (szlachta) power were guaranteed as unchangeable parts of this new constitution.

Poland was also forced to sign a treaty with Russia. In this treaty, Catherine was made the protector (guarantor) of the Polish political system. The system could not be changed without Russia's approval. So, the Commonwealth became, in reality, a Russian protectorate. The real power in Poland lay with the Russian ambassadors. The Polish king largely carried out their wishes.

This situation led to a Catholic uprising and civil war in 1768, known as the Confederation of Bar. This was a group of Polish nobles who fought against the King and Russian forces until 1772. They wanted to cancel the Empress's orders. The Confederation's war and defeat partly led to a partition of the Commonwealth. Its neighbors took parts of its outer territories. Although Catherine initially opposed partition, King Frederick II of Prussia wanted more land. He also wanted to balance Austria's military power. So, he promoted a partition plan that would benefit all three countries. Emperor Joseph II of the Habsburg monarchy and then Empress Catherine agreed. In 1772, Russia, Prussia, and Austria forced the partition terms on the helpless Commonwealth. They claimed they were stopping chaos and restoring order.

National Revival

The first partition in 1772 did not directly threaten the Polish-Lithuanian state's stability. Poland still had a lot of land, including its main Polish areas. Also, the shock of losing land made it clear how dangerous the decay in government was. This created a desire for reforms, following the ideas of the European Enlightenment. King Stanisław August supported the progressive people in the government. He promoted the ideas of foreign political figures like Edmund Burke and George Washington.

Polish thinkers studied and discussed Enlightenment philosophers like Montesquieu and Rousseau. During the Enlightenment in Poland, the idea of democratic institutions for all social classes was accepted by more progressive groups in Polish society. Education reform included creating the first ministry of education in Europe (the Commission of National Education). Taxes and the army were thoroughly reformed. A central executive government was created as the Permanent Council. Landowners freed many peasants, though there was no official government law. Polish cities and businesses, which had been declining for decades, were revived by the Industrial Revolution, especially in mining and textiles.

Stanisław August's reforms reached their peak after three years of intense debate. The "Great Sejm" produced the Constitution of May 3, 1791. Historian Norman Davies called it "the first constitution of its kind in Europe." It was inspired by the liberal spirit of the American constitution written at the same time. The constitution changed Poland-Lithuania into a hereditary monarchy. It got rid of many strange and old features of the old government system. The new constitution ended the individual veto in parliament. It separated powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. It also established "people's sovereignty" for the noble and bourgeois classes. Although it was never fully put into practice, the Constitution of May 3 became a cherished part of Polish political heritage. Its anniversary is marked as the country's most important civic holiday.

Poland-Lithuania's End

The passing of the constitution worried many nobles. Some of them would lose significant power under the new system. In countries with absolute rulers like Russia, the democratic ideas of the new constitution also threatened the existing order. The possibility of Poland becoming strong again threatened to end foreign control over Polish affairs. In 1792, Polish conservative groups formed the Confederation of Targowica. They asked Russia for help to restore the old ways. Empress Catherine was happy to use this chance. With Prussian support, she invaded Poland. She claimed she was defending Poland's old liberties. A defensive war against powerful Russian armies was fought in 1792 with some success. But the undecided Stanisław August did not believe it was possible to defeat the Russian Empire. He gave up and joined the Targowica Confederation. Arguing that Poland had fallen to radical ideas like those in France, Russia and Prussia canceled the Constitution of May 3. They carried out the Second Partition of Poland in 1793. The rest of the country was then occupied by Russian troops.

The Second Partition was much worse than the first. Russia received a huge area of eastern Poland, reaching almost to the Black Sea. To the west, Prussia received an area called South Prussia. This was almost twice the size of what it gained in the First Partition along the Baltic. It also got the port of Danzig (Gdańsk). Poland's neighbors thus reduced the Commonwealth to a small state. They showed their intention to get rid of it completely when it was convenient for them.

The Kościuszko Uprising, a big Polish revolt, broke out in 1794. It was led by Tadeusz Kościuszko, a military officer who had served well in the American Revolution. Kościuszko's rebel armies, made up of various groups, won some early successes. But they eventually fell to the stronger forces of Russian General Alexander Suvorov. After the uprising of 1794, Russia, Prussia, and Austria carried out the third and final partition of Poland-Lithuania in 1795. This erased the Commonwealth of Two Nations from the map. They promised never to allow it to return.

Much of Europe condemned this division as an international crime without equal in history. However, with the distractions of the French Revolution and its wars, no state actively opposed the final takeovers. In the long run, the breakup of Poland-Lithuania upset the traditional balance of power in Europe. It greatly increased Russia's influence. It also paved the way for the powerful Germany that would emerge in the 19th century, with Prussia at its core. For the Poles, the Third Partition began a period of continuous foreign rule that would last for well over a century.

See also

- History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1648)

- History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1648–1764)

- History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1764–1795)

- List of Polish rulers

- List of Polish nobles

- Ambassadors and envoys from Russia to Poland (1763–1794)