History of medieval Tunisia facts for kids

The medieval era of Tunisia began when the land, called Ifriqiya back then, returned to local Berber rule. This happened after the Shi'a Fatimid Caliphate moved to Egypt. They left the Zirid family in charge. The Zirids later broke away from the Fatimids and became Sunni Muslims.

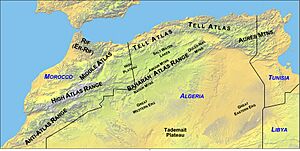

During this time, two strong movements appeared in the Maghreb (North Africa). They wanted to make sure Muslims practiced their faith purely. The Almoravids started in the far west (modern Morocco). They built an empire that reached Spain and Mauritania. However, their rule never included Ifriqiya. Later, a Berber religious leader named Ibn Tumart started the Almohad movement. They took over from the Almoravids and controlled much of North Africa and Spain. The Hafsids, a local Berber family from Tunis, then took over from the Almohads. They ruled with different levels of success until the Ottomans arrived in the western Mediterranean.

Contents

Berber Rule Returns to Tunisia

After the Fatimids, Ifriqiya (Tunisia) was ruled by local Berbers for over 500 years (1048−1574). The Fatimids were a special kind of Shi'a Muslim called Isma'ili. They came from lands far to the east. Today, most Tunisians are Sunni Muslims, who are different from the Shi'a.

At the time of the Fatimids, many people in Ifriqiya did not like being ruled by anyone from the east, whether Sunni or Shi'a. This feeling helped local Berber leaders rise to power. It marked a new time of Berber self-rule in medieval Tunisia.

At first, the Fatimids gained support from local Berber groups. They used the Berbers' dislike of eastern rule, like the Aghlabids. This helped the Fatimids gain power in Ifriqiya. However, once they were in charge, the Fatimids caused problems. They charged high, unusual taxes, which led to a Kharijite revolt.

Later, the Fatimids of Ifriqiya achieved their big goal: conquering Egypt. Their leaders then moved to Cairo. They left the Berber Zirids to govern the Maghrib as their local helpers. The Zirids were originally just clients of the Fatimid Shi'a Caliphate in Egypt. But they eventually kicked the Fatimids out of Ifriqiya. In return, the Fatimids sent the disruptive Banu Hilal tribes to Ifriqiya. This caused a time of chaos and economic problems.

The independent Zirid family was seen as a Berber kingdom. They were founded by a leader from the Sanhaja Berbers. At the same time, the Sunni Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba in Spain fought against the Shi'a Fatimids. Tunisians have long been Sunnis themselves, so they might feel some pride in the Fatimids' role in Islamic history. Besides the problems with the Banu Hilal, the Fatimid era also saw the cultural leadership of North Africa move away from Ifriqiya and towards al-Andalus (Spain).

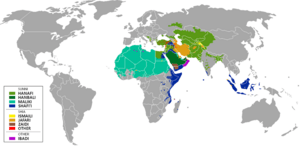

During the time of Shi'a rule, the Berber people seemed to change their views. They moved from being against the Islamic east to accepting its Sunni beliefs. This was done through their own Maliki school of law, which is one of the four main Sunni schools. Professor Abdallah Laroui notes that the Berber Maghrib tried different religious ideas from the 9th to the 13th centuries. These included Khariji, Zaydi, Shi'a, and Almohad beliefs. Finally, they settled on the Maliki Sunni teachings. This shows a great period of Berbers defining themselves.

Under the Almohads, Tunis became the permanent capital of Ifriqiya. The disagreements between Berbers and Arabs started to lessen. It could be said that the history of Ifriqiya before this time was just a warm-up. From then on, the important events shaped the history of Tunisia for its modern people. Professor Perkins mentions the earlier rule from the east. He says that after the Fatimids left, Tunisia aimed to create a "Muslim state focused on the interests of its Berber majority." This began the medieval era of their self-rule.

Berber Language History

How Migrations Changed Languages

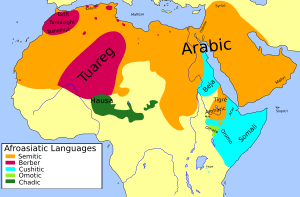

About twenty Berber languages (also called Tamazight) are spoken in North Africa. Berber speakers used to be found all over this large area. But because of Arabization (people adopting Arabic) and later migrations, today Berber languages are spoken in only a few large regions. These are mainly in Morocco, Algeria, and the central Sahara. There are also smaller areas where Berber is spoken. Some language experts say that Berber is one language with many different ways of speaking it, spread out in separate areas. There isn't one standard way of speaking it.

Here are some main Berber language groups:

- Guanche (now extinct) - spoken in the Canary Islands.

- Old Libyan (now extinct) - spoken west of ancient Egypt.

- Berber Proper:

It's important to know that how Berber languages are grouped and named can vary among experts.

Writing Systems and Old Texts

The Libyan Berbers created their own writing system around the 4th century BC. It came from the Phoenician alphabet. This writing was boustrophic, meaning it was written left-to-right, then right-to-left on the next line, or sometimes up and down in columns. Most of these early writings were short and found on tombs.

There are a few longer texts from Thugga, which is modern Dougga in Tunisia. These texts are bilingual, written in both Punic (with its letters) and Berber (with its letters). One text tells us about how the Berbers governed themselves in the 2nd century BC. Another text starts: "This temple the citizens of Thugga built for King Masinissa...." Today, a writing system called Tifinagh is still used, and it comes from this ancient Libyan script.

Berber is not widely spoken in Tunisia today. Centuries ago, many of its Zenata Berbers adopted Arabic. Today, the small number of people who speak Berber in Tunisia can be found on Jerba island, near the salt lakes, and close to the desert. It's also spoken along the mountainous border with Algeria. In contrast, Berber is quite common in Morocco, Algeria, and the remote central Sahara. Berber poetry and traditional Berber literature still exist.

Berber Tribal Groups

The main Berber tribal groups in ancient times were the Mauri, the Numidians, and the Gaetulians. The Mauri lived in the far west (modern Morocco and central Algeria). The Numidians were between the Mauri and the city of Carthage. Both had many people who lived in settled places. The Gaetulians moved around more, often with their animals, and lived in the southern areas near the Sahara.

The medieval historian of the Maghrib, Ibn Khaldun, wrote about how different tribal groups changed over time. There's a lot of discussion about how tribal economies and their influence worked. Some critics say this topic is overblown. Abdallah Laroui believes that focusing on tribes hides other issues, especially those linked to colonial ideas. While Berber tribal society did affect culture and government, their survival was mainly due to strong outside interference. This interference took over the main role of government institutions and stopped their natural political growth. Instead of being naturally inclined to tribal structures, Berbers used their strong tribal networks to survive foreign occupation. However, it's also true that tribal societies in the Middle East have existed for thousands of years and sometimes thrived.

Berber tribal identities stayed strong even during the long rule of Carthage and centuries of Roman rule. Their social customs helped them survive. These included: defending themselves as a group, group responsibility, marriage alliances, shared religious practices, giving gifts to each other, and family working together to create wealth. Abdallah Laroui sums up the lasting effects under foreign rule (Carthage and Rome) as: Social (assimilated, non-assimilated, free); Geographical (city, country, desert); Economic (trade, farming, nomadism); and, Linguistic (like Latin, Punico-Berber, Berber).

In the early centuries of the Islamic era, Berber tribes were said to be divided into two main groups: the Butr (Zanata and their allies) and the Baranis (Sanhaja, Masmuda, and others). The meaning of these names is not clear. They might come from clothing customs ("abtar" and "burnous"), or words used to tell nomads (Butr) from farmers (Baranis). The Arabs first recruited most of their soldiers from the Butr.

Later, stories appeared about an ancient invasion of North Africa by the Himyarite Arabs from Yemen. From this, a made-up history was created: that Berbers came from two brothers, Burnus and Abtar, who were sons of Barr. Barr was the grandson of Canaan (who was Noah's grandson through his son Ham). Both Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) and Ibn Hazm (994-1064), as well as Berber family historians, said this Himyarite Arab ancestry was completely false. However, this legendary ancestry played a part in the long process of Arabization that continued for centuries among the Berber peoples.

In their medieval Islamic history, the Berbers can be divided into three major tribal groups: the Zanata, the Sanhaja, and the Masmuda. These groups are mentioned by Ibn Khaldun. The Zanata allied more closely with the Arabs early on and became more Arabized. However, Znatiya Berber is still spoken in small areas across Algeria and northern Morocco. The Sanhaja are also spread widely throughout the Maghrib. This includes the settled Kabyle on the coast west of modern Algiers, the nomadic Zanaga of southern Morocco and the western Sahara, and the Tuareg, who are famous camel-herding nomads of the central Sahara. The descendants of the Masmuda are settled Berbers of Morocco, in the High Atlas mountains, and from Rabat inland. This is the most populated of the modern Berber regions.

Medieval events in Ifriqiya and al-Maghrib often involved these tribal groups. The Kutama tribes, linked to the Kabyle Sanhaja, helped establish the Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171). Their helpers and later rulers in Ifriqiya, the Zirids (973-1160), were also Sanhaja. The Almoravids (1056–1147) started far south of Morocco, among the Lamtuna Sanhaja. From the Masmuda came Ibn Tumart and the Almohad movement (1130–1269), who were later supported by the Sanhaja. The Hafsid dynasty (1227–1574) of Tunis also came from the Masmuda.

Zirid Berber Rule

Under Fatimid Influence

The Zirid dynasty (972-1148) started as helpers of the Shi'a Fatimids (909−1171). The Fatimids had conquered Egypt in 969. After moving their capital from Mahdiya in Ifriqiya to Cairo, the Fatimids stopped directly governing the Maghrib. They gave this job to a local helper. However, they didn't give power to a loyal Kotama Berber, even though this tribe had greatly helped the Fatimids rise to power. Instead, authority was given to a chief from the Sanhaja Berber group, Buluggin ibn Ziri (died 984). His father, Ziri, had been a loyal supporter and soldier for the Fatimids.

For a while, the region was very rich, and the early Zirid court was known for its luxury and arts. But political life was unstable. Buluggin's war against the Zenata Berbers to the west didn't achieve much. His son, al-Mansur (ruled 984-996), challenged the Fatimid Shi'a Caliphate in Cairo, but it didn't work as he planned. Instead, the Kotama Berbers rebelled, encouraged by the Fatimids. Al-Mansur managed to control the Kotama. The Fatimids continued to demand payments from the Zirids. After Buluggin's death, the Fatimid control was split between two families: the Zirids (972−1148) for Ifriqiya, and the Hammadids (1015–1152) for western lands (in modern Algeria). The Hammadids were named after Hammad, another descendant of Buluggin. Life became less safe because of constant political fights between the Zirids and Hammadids, including a civil war in 1016. There were also armed attacks from the Sunni Umayyads of al-Andalus and from other Berbers, like the Zanatas of Morocco.

Even though the Maghrib often faced conflict and political confusion during this time, the Fatimid province of Ifriqiya at first stayed relatively rich under the Zirid Berbers. Farming was strong (grains and olives), as were city artisans (weavers, metalworkers, potters), and trade across the Sahara. The holy city of Kairouan was also the main political and cultural center of the Zirid state. However, the Saharan trade soon began to decline. This was due to changing demand and competition from rival traders: from Fatimid Egypt to the east, and from the rising power of the al-Murabit Berber movement in Morocco to the west. This decline in Saharan trade quickly hurt Kairouan's economy. To make up for it, the Zirids encouraged sea trade from their coastal cities, which started to grow. But they faced tough competition from Mediterranean traders from the rising city-states of Genoa and Pisa.

Becoming Independent

In 1048, for both money and popular reasons, the Zirids completely broke away from the Shi'a Fatimid Caliphate, who ruled them from Cairo. Instead, the Zirids chose to become Sunni (which most Maghribi Muslims always preferred). They then declared their loyalty to the old Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad. As a result, many Shi'a were killed during unrest across Ifriqiya. The Zirid state took Fatimid wealth and coins. Sunni Maliki religious judges were brought back as the main legal authority.

In revenge, the Fatimid leaders sent an invasion of nomadic Arabians, the Banu Hilal, against the Zirids. These tribes had already moved into upper Egypt. The Fatimids convinced these warrior Bedouins to continue west into Ifriqiya. The entire Banu Hilal, along with the Banu Sulaym, both Arab tribes, left upper Egypt where they had been grazing their animals, and moved towards Zirid Ifriqiya.

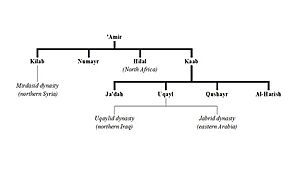

The arriving Bedouins of the Banu Hilal defeated the Zirid and Hammadid Berber armies in 1057. They then looted the Zirid capital, Kairouan. It has been said that many of the Maghrib's later problems came from the chaos and decline caused by their arrival, though not all historians agree. In Arab stories, the Banu Hilal's leader Abu Zayd al-Hilali is a hero. He has a victory parade in Tunis where he is made lord of al-Andalus, according to the folk epic Taghribat Bani Hilal. The Banu Hilal came from the tribal group Banu 'Amir, mostly from southwest Arabia.

In Tunisia, as the Banu Hilali tribes looted the countryside, local settled people had to find safety in the main coastal cities and fortified towns in northern Tunisia (like Tunis, Sfax, Mahdia, Bizerte). During this time, Tunisia quickly became more urban as famines emptied the countryside. Industry shifted from farming to making goods. The rich farming lands of central and northern Ifriqiya became grazing lands for a while. As a result, the economy went into a sharp decline.

Even after the Zirids fell, the Banu Hilal caused disorder, like in the 1184 uprising of the Banu Ghaniya. However, these new Arab arrivals brought a second large wave of Arab immigration into Ifriqiya. This sped up the process of Arabization. The use of Berber languages decreased in rural areas because of the Bedouin's power. Greatly weakened, Sanhaja Zirid rule continued, but society was disrupted, and the regional economy was in chaos.

Normans on Tunisia's Coast

Normans from Sicily first attacked the east coast of Ifriqiya in 1123. After several years of attacks, in 1148, Normans led by George of Antioch conquered all the coastal cities of Tunisia. These included Bona (Annaba), Mahdia, Sfax, Gabès, and Tunis.

The Norman king Roger II of Sicily managed to create a coastal kingdom between Bona and Tripoli. This lasted from 1135 to 1160. It was mainly supported by the last local Christian communities.

These Christian communities, usually North African people (Roman Africans) who had kept their religion since the Roman Empire, still spoke African Romance in a few places like Gabès and Gafsa. The most important proof of African Romance comes from the 12th-century Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi. He wrote that the people of Gafsa (in central-south Tunisia) used a language he called al-latini al-afriqi ("the Latin of Africa").

Berber Islamic Movements

In the medieval Maghrib, among the Berber tribes, two strong religious movements appeared one after the other: the Almoravids (1056–1147) and the Almohads (1130–1269). Professor Jamil Abun-Nasr compares these movements to the 8th and 9th-century Kharijites in the Maghrib. All were strong Berber movements with deep Muslim faith. They all rebelled against a relaxed way of practicing religion and wanted to create a state where "living a good Muslim life was the main goal of politics." These medieval Berber movements, the Almoravids and the Almohads, have been compared to the more recent Wahhabis, who are strict fundamentalists in Saudi Arabia.

The Almoravids (Arabic al-Murabitum, meaning "defenders") started as an Islamic movement of the Sanhaja Berbers. They came from the remote deserts of the southwest Maghrib. After a century, this movement lost its strength and became less strict. From their capital Marrakech, the Almoravids had once ruled a large empire. It stretched from Mauritania (south of Morocco) to al-Andalus (southern Spain). However, Almoravid rule never reached far enough east to include Ifriqiya.

The rival Almohads were also a Berber Islamic movement. Their founder came from the Masmuda tribe. They defeated and replaced the Almoravids. They then built a large empire that included the region of Ifriqiya, which the Zirids had ruled.

Almohads: The Unitarians

The Mahdi and His Teachings

The Almohad movement (Arabic al-Muwahhidun, meaning "the Unitarians") ruled in the Maghrib from about 1130 until 1248 (and locally in Morocco until 1275). This movement was founded by Ibn Tumart (1077–1130). He was a Masmuda Berber from the Atlas mountains of Morocco and became known as the mahdi. After going on a pilgrimage to Mecca and studying, he returned to the Maghrib around 1218. He was inspired by the teachings of al-Ash'ari and al-Ghazali.

Ibn Tumart was a powerful leader who taught about the deep meaning of God's Oneness. He was a strict reformer and gathered many followers among the Berbers in the Atlas mountains. He created a strong community and eventually started an armed challenge against the rulers at the time, the Almoravids (1056–1147).

Ibn Tumart, the Almohad founder, wrote down his ideas, which mixed religious beliefs with politics. In his writings, he claimed that the leader, the mahdi, could not make mistakes. Ibn Tumart set up a system of leaders among his followers that lasted long after the Almohad era. This system was based on ethnic loyalty, like the "Council of Fifty" and the assembly of "Seventy." But more importantly, he created a formal structure for an inner group of leaders that went beyond tribal loyalties. This included his "people of the house" (a private council), his "Ten" (his first ten strong followers), and various other roles.

Ibn Tumart trained his own talaba (ideologists) and huffaz (who had both religious and military duties). While some details are unclear, it's generally agreed that Ibn Tumart wanted to reduce the "influence of the traditional tribal framework." Later historical changes "were greatly helped by his original reorganization because it allowed tribes to work together" when they might not have otherwise. These organizing efforts by Ibn Tumart were "very careful and effective" and a "conscious copy" of how Medina was organized during the time of Muhammad.

The mahdi Ibn Tumart also strongly supported the idea that strict Islamic law and morals should replace unusual Berber customs. At his early base in Tinmal, Ibn Tumart acted as "the guardian of the faith, the judge of moral questions, and the chief judge." However, because of the strict legalism common among Maliki judges at the time and their influence in the rival Almoravid government, Ibn Tumart opposed the Maliki school of law. Instead, he preferred the Zahirite school.

Building a Unified Empire

After the Mahdi Ibn Tumart's death, Abd al-Mu'min al-Kumi (c. 1090 – 1163) became the Almohad caliph around 1130. He was the first non-Arab to take this title. Abd al-Mu'min was one of Ibn Tumart's original "Ten" followers. He immediately attacked the ruling Almoravids and took Morocco from them by 1147. He also put down later revolts there. Then he crossed the straits and took over al-Andalus (in southern Spain). However, Almohad rule there was not always stable. Abd al-Mu'min spent many years "organizing his state internally to establish the Almohad government in his family." He "tried to create a unified Muslim community in the Maghrib based on Ibn Tumart's teachings."

Meanwhile, the chaos in Zirid Ifriqiya (Tunisia) made it an easy target for the Norman kingdom in Sicily. Between 1134 and 1148, the Normans took control of Mahdia, Gabès, Sfax, and the island of Jerba. These were important centers for business and trade. The only strong Muslim power in the Maghreb at that time was the newly rising Almohads, led by their Berber caliph Abd al-Mu'min. He responded with several military campaigns into the eastern Maghrib. These campaigns took over the Hammadid and Zirid states and removed the Christians. In 1152, he first attacked and occupied Bougie (in eastern Algeria), which was ruled by the Sanhaja Hammadids. His armies then entered Zirid Ifriqiya, which was disorganized, and took Tunis. His armies also surrounded Mahdia, held by Normans from Sicily, forcing these Christians to agree to leave in 1160. However, Christian merchants, for example from Genoa and Pisa, had already arrived to stay in Ifriqiya. So, foreign merchants (Italian and Aragonese) continued to be present.

With the capture of Tunis, Mahdia, and later Tripoli, the Almohad state stretched from Morocco to Libya. "This was the first time that the Maghrib was united under one local political authority." "Abd al-Mu'min briefly led a unified North African empire—the first and last in its history under local rule." This would be the peak of political unity in the Maghrib. However, twenty years later, by 1184, a revolt in the Balearic Islands by the Banu Ghaniya (who claimed to be the heirs of the Almoravids) spread to Ifriqiya and other places. This caused serious problems for the Almohad government, on and off, for the next fifty years.

Culture and Ideas

Ibn Tumart had refused to accept the fiqh (Islamic law) of any established school. However, in practice, the Maliki school of law survived. Eventually, Maliki judges were officially recognized, except during the rule of Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur (1184–1199), who was loyal to Ibn Tumart's teachings. This unclear situation continued on and off, though it often didn't work well. After a century of this back and forth, the caliph Abu al-'Ala Idris al-Ma'mun broke with the strict ideas of the Almohad rulers. Around 1230, he brought back the Maliki rite, which was always popular in the Maghrib.

The Muslim philosophers Ibn Tufayl (known as Abubacer in Latin) from Granada (died 1185) and Ibn Rushd (Averroës) from Córdoba (1126–1198) were important figures. Ibn Rushd was also appointed a Maliki judge. Both were known at the Almohad court, whose capital became Marrakech. The Sufi master theologian Ibn 'Arabi was born in Murcia in 1165. Under the Almohads, architecture thrived. The Giralda tower was built in Seville, and the pointed arch was introduced.

"There is no better sign of the Almohad empire's importance than the fascination it held for all later rulers in the Maghrib." It was an empire inspired by Berbers, and its success was guided by Berber leaders. The Almohads gradually changed their original goal of strictly following their founder's plans. In this way, the Almohads were similar to the earlier Almoravids (also Berber). However, their movement probably helped deepen the religious awareness of Muslim people across the Maghrib. Still, it could not stop other traditions and teachings, and other ways of expressing Islam survived. These included the popular worship of saints, the sufis, and the Maliki judges.

The Almohad empire (like the Almoravid before it) eventually weakened and fell apart. Spain was lost, except for the Muslim Kingdom of Granada. In Morocco, the Almohads were followed by the Merinids. In Ifriqiya (Tunisia), they were followed by the Hafsids, who claimed to be the true heirs of the Almohad movement.

Hafsid Dynasty of Tunis

The Hafsid dynasty (1230–1574) took over from the Almohads in Ifriqiya. The Hafsids claimed to carry on the true spiritual legacy of the Almohad founder, the Mahdi Ibn Tumart (c. 1077 – 1130). For a short time, a Hafsid ruler was even recognized as the Caliph of Islam. Tunisia under the Hafsids would eventually regain its cultural importance in the Maghrib for a while.

How the Hafsids Ruled

Abu Hafs 'Umar Inti was one of the Ten, a very important group of early followers of the Almohad movement, around 1121. These Ten were companions of Ibn Tumart the Mahdi. They formed an inner circle that was consulted on all important matters. Abu Hafs 'Umar Inti, who was wounded in battle near Marrakesh in 1130, was a powerful figure within the Almohad movement for a long time. His son, 'Umar al-Hintati, was appointed governor of Ifriqiya by the Almohad caliph Muhammad an-Nasir in 1207 and served until his death in 1221. His son, Abu Zakariya, was the grandson of Abu Hafs.

Abu Zakariya (1203–1249) served the Almohads in Ifriqiya as governor of Gabès, then in 1226 as governor of Tunis. In 1229, during problems within the Almohad movement, Abu Zakariya declared his independence. He had the Mahdi's name announced at Friday prayers, but he took the title of Amir (prince). This marked the start of the Hafsid dynasty (1229–1574). In the next few years, he secured his control over the cities of Ifriqiya. Then he captured Tripolitania (1234) to the east, and to the west, Algiers (1235) and later Tlemcen (1242). He strengthened his rule among the Berber groups. The Hafsid government followed the Almohad model, which was a very strict and centralized system. Abu Zakariya's claim to continue the Almohad movement was accepted as the only state keeping Almohad traditions. Many states in Al-Andalus and Morocco (including the Merinids) recognized him in Friday prayers. Diplomatic relations were opened with Frederick II of Sicily, Venice, Genoa, and Aragon. Abu Zakariya, the founder of the Hafsids, became the most important ruler in the Maghrib.

For a historic moment, the son of Abu Zakariya and self-declared caliph of the Hafsids, al-Mustansir (ruled 1249-1277), was recognized as Caliph by Mecca and the Islamic world (1259–1261). This happened after the Abbasid caliphate was ended by the Mongols in 1258. However, this moment passed as a rival claimed the title. The Hafsids remained a local power.

Since their beginnings with Abu Zakariya, the Hafsids presented their rule as the heir to the Almohad movement founded by the Mahdi Ibn Tumart. His name was used during Friday prayers in the emirate's mosques until the 15th century. The Hafsid government was set up following the Almohad model created by the Mahdi. This meant it was a very strict hierarchy. The Amir held all power, with special rules of behavior around him, though he didn't always keep himself distant. The Amir's advisors were the Ten, made up of the chief Almohad shaiks. Next were the Fifty, gathered from smaller shaiks, with ordinary shaiks after them. The early Hafsids had a censor, the mazwar, who oversaw the ranking of the chosen shaiks and put them into specific groups.

Originally, there were three ministers (wazir, plural wuzara): one for the army (commander and supplies), one for finance (money and taxes), and one for the state (letters and police). Over the centuries, the role of Hajib became more important. At first, this person was the head of the palace, then a link between the Amir and his cabinet, and finally, effectively the first minister. The state's power was publicly shown through impressive processions. High officials on horseback paraded to the sound of kettledrums and tambourines, with colorful silk banners held high. All this was to create a grand display. In areas where the Amir had recognized authority, his governors were usually close family members, helped by an experienced official. Elsewhere, provincial appointees had to deal with strong local powerful families. For rural tribes, different methods were used. For those on good terms, their tribal shaik might work as a double agent, representing them to the government and also acting as a government agent to his tribe members.

In 1270, King Louis IX of France, whose brother was the king of Sicily, landed an army near Tunis. Disease badly affected their camp. Later, Hafsid influence was reduced by the rise of the Moroccan Marinids of Fez. They captured and lost Tunis twice (1347 and 1357). However, the Hafsids would recover. Two important rulers were Abu Faris (1394–1434) and his grandson Abu 'Amr 'Uthman (ruled 1435–1488).

Towards the end, internal problems within the Hafsid dynasty made them weak. At the same time, a big power struggle began between Spain and the Ottoman Turks over control of the Mediterranean. The Hafsid rulers became like pawns, caught between the plans of these two powerful sides. By 1574, Ifriqiya had become part of the Ottoman Empire.

Society and Culture Under the Hafsids

After a break under the Almohads, the Maliki madhhab (school of law) fully returned to its traditional role in the Maghrib. During the 13th century, the Maliki school changed quite a bit, becoming more flexible, partly due to influence from Iraq. Under Hafsid legal experts, the idea of maslahah or "public interest" developed in how their madhhab worked. This allowed Maliki fiqh (Islamic law) to consider what was needed and the circumstances for the general good of the community. This way, local custom was allowed into the Sharia of Malik, becoming a part of the legal system. Later, the Maliki religious scholar Muhammad ibn 'Arafa (1316–1401) of Tunis studied at the Zaituna library, which was said to have 60,000 books.

Bedouin Arabs continued to arrive into the 13th century. With their ability to raid and fight still strong, they remained a challenging and influential group. The Arabic language became dominant, except for a few Berber-speaking areas, like Kharijite Djerba and the desert south. An unfortunate division grew between the rule of the cities and that of the countryside. Sometimes, the city-based rulers would grant rural tribes independence in exchange for their support in fights within the Maghrib. However, this tribal independence from the central authority also meant that when the central government became weak, the outer areas might still remain strong and resilient.

From al-Andalus (Spain), Muslim and Jewish people continued to move to Ifriqiya, especially after the fall of Granada in 1492. Granada was the last Muslim state ruling on the Iberian peninsula. These new immigrants brought their highly developed arts. The well-regarded Andalusian traditions of music and poetry are discussed by Ahmad al-Tifashi (1184–1253) of Tunis. He wrote about them in his Muta'at al-Asma' fi 'ilm al-sama' (Pleasure to the Ears, on the Art of Music), in volume 41 of his encyclopedia.

Because of the initial wealth, Al-Mustansir (ruled 1249-1277) changed the capital city of Tunis. He built a palace and the Abu Fihr park. He also created an estate near Bizerte (which Ibn Khaldun said was unmatched in the world). Education improved with the creation of a system of madrasahs (schools). Sufism, for example, Sidi Bin 'Arus (died 1463 in Tunis), who founded the Arusiyya tariqah (Sufi order), became more and more important. It created social connections between the city and the countryside. The Sufi shaikhs began to take on the religious authority once held by the Almohads, according to Abun-Nasr. Poetry flourished, as did architecture. For a time, Tunisia had regained cultural leadership of the Maghrib.

Trade and Business

Tunisia under the early Hafsids, and the entire Maghrib, enjoyed general wealth because of the rise of the Saharan-Sudanese trade. Perhaps more important was the increase in Mediterranean trade, including trade with Europeans. Across the region, repeated buying and selling with Christians led to the development of trading practices and organized shipping. These were designed to ensure safety for both sides, customs revenue, and business profit. A ship could arrive, unload its goods, and pick up new cargo in just a few days. Christian merchants from the Mediterranean, usually organized by their home city, set up their own trading facilities (a funduq) in these North African ports. These facilities handled the flow of goods and marketing.

The main sea ports for customs were then: Tunis, Sfax, Mahdia, Jerba, and Gabés (all in Tunisia); Oran, Bougie (Béjaïa), and Bône (Annaba) (in Algeria); and Tripoli (in Libya). At these ports, imports were generally unloaded and moved to a customs area. From there, they were stored in a sealed warehouse, or funduq, until duties and fees were paid. The amount charged varied, usually five or ten percent. The Tunis customs service was a structured system with different levels of officials. At its head was often a member of the ruling nobility or musharif, called al-Caid. He not only managed the staff collecting duties but also might negotiate trade agreements, sign treaties, and act as a judge in legal disputes involving foreigners.

Tunis exported grains, dates, olive oil, wool and leather, wax, coral, salted fish, cloth, carpets, weapons, and possibly black slaves. Imports included furniture, weapons, hunting birds, wine, perfumes, spices, medicinal plants, hemp, linen, silk, cotton, many types of cloth, glass items, metals, hardware, and jewels.

Islamic law during this era developed a specific system to control community morals, called hisba. This included keeping order and safety in public markets, supervising market deals, and related matters. The city marketplace (Arabic souk, plural iswak) was usually a street with shops selling the same or similar goods (vegetables, cloth, metalware, wood, etc.). The city official in charge of these duties was called the muhtasib.

To keep public order in the city markets, the muhtasib would make sure trade was fair. This meant merchants truthfully quoted the local price to rural people and used honest weights and measures. However, they didn't control the quality of goods or the price itself. They also kept roads open, regulated the safety of building construction, and checked the metal value of existing coins and the making of new coins (gold dinars and silver dirhems were minted at Tunis). The authority of the muhtasib, with his group of helpers, was somewhere between a qadi (judge) and the police. Or sometimes, it was like a public prosecutor (or trade commissioner) and the mayor (or a high city official). Often, a leading judge or mufti held the position. The muhtasib did not hear legal arguments in court. However, he could order punishments like up to 40 lashes, send someone to debtor's prison, order a shop closed, or expel an offender from the city. But the muhtasib's power did not extend to the countryside.

Starting in the 13th century, Muslim and Jewish immigrants came from al-Andalus with valuable skills. These included trade connections, farming techniques, manufacturing, and arts. However, general wealth was not steady throughout the centuries of Hafsid rule. There was a sharp economic decline starting in the mid-14th century due to various reasons, such as problems with farming and the Sahara trade. Under the amir Abu al-'Abbas (1370–1394), Hafsid involvement in Mediterranean trade began to decline, while early corsair (pirate) raiding activity started.

Ibn Khaldun: A Great Thinker

His Life and Work

Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) was a major social philosopher. He is known as a pioneer in sociology, history writing, and related fields. Although his family came from Yemen, they had lived in al-Andalus (Spain) for centuries before moving to Ifriqiyah in the 13th century. As someone born in Tunis, he spent much of his life under the Hafsids. He sometimes worked for their government.

Ibn Khaldun started a political career early. He worked for different rulers of small states, whose plans changed with shifting rivalries and alliances. At one point, he became a vizier (a high official). However, he also spent a year in prison. His career required him to move several times, for example, to Fez, Granada, and eventually Cairo, where he died. To write his books, he took a break from active political life. Later, after his pilgrimage to Mecca, he served as the Grand Qadi (chief judge) of the Maliki rite in Egypt. He was appointed and dismissed several times. While he was visiting Damascus, Tamerlane took the city. This cruel conqueror interviewed the elderly judge and social philosopher. However, Ibn Khaldun managed to escape back to his life in Egypt.

His Ideas on Society

The history and history writing by Ibn Khaldun were shaped by his knowledge as a faylasuf (philosopher). But it was his involvement in the small, unstable governments of the region that gave him many of his key ideas. His history tries to explain the repeating pattern of historical states in the Maghrib. This pattern is: (a) a new ruling group comes to power with strong loyalties, (b) these loyalties fall apart over several generations, (c) leading to the collapse of the ruling group. The social cohesion needed for a group's initial rise to power, and for its ability to keep and use that power, Ibn Khaldun called Asabiyyah.

His seven-volume Kitab al-'Ibar (Book of Examples) is a shortened "universal" history. It focuses on the Persian, Arab, and Berber civilizations. Its long introduction, called the Muqaddimah (Introduction), describes the development of long-term political trends and events as something to study. He saw them as human phenomena, using ideas similar to sociology. It is widely considered a brilliant and deep analysis of culture. Unfortunately, Ibn Khaldun did not get enough interest from local scholars, and his studies were ignored in Ifriqiyah. However, in the Persian and Turkish worlds, he gained a lasting following.

In the later books of the Kitab al-'Ibar, he focuses especially on the history of the Berbers of the Maghrib. The insightful Ibn Khaldun eventually writes about historical events he himself saw or experienced. As an official of the Hafsids, Ibn Khaldun saw firsthand how troubled governments and the long-term decline in the region's fortunes affected the social structure.

Images for kids

See also