History of the Choctaw facts for kids

The Choctaw people, also known as Chahtas, are a Native American group. They originally lived in the southeastern part of what is now the United States. The Choctaw are famous for quickly learning to write after Europeans arrived. They also adopted new farming ways and some customs from other groups. Their story is full of changes, challenges, and strength.

Contents

- Early Choctaw History

- The Choctaw Nation Forms

- Relations with the United States

- American Revolutionary War

- After the American Revolution

- Hopewell Treaty (1786)

- War of 1812

- Doak's Stand Treaty (1820)

- Negotiations with the U.S. Government (1820s)

- The 1830 Election and Treaty

- Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830)

- The Removal Era

- Pre-Civil War (1840)

- 1853 World's Fair

- American Civil War (1861)

- After the Civil War: Reconstruction (1865)

- Mississippi Choctaw Delegation to Washington (1914)

- World War I (1918)

- Reorganization (1934)

- World War II (1941)

- After Reorganization

- Modern Choctaw History

- Choctaw Population History

Early Choctaw History

Ancient Mississippian Culture

From about 800 to 1500 CE, the ancestors of the Choctaw and Chickasaw people lived in the Mississippian era. They were likely connected to a large community around Moundville in Alabama. This Mississippian culture was a big network for religion, trade, and culture. It stretched along the Mississippi River valley across much of the eastern and southern United States.

When the Spanish first explored inland in the 1500s, they met some of these Mississippian groups. These groups were led by powerful chiefs.

First Contact with Europeans

After Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca returned to Spain, he told the King about the "richest country in the world." So, Spain sent Hernando de Soto to explore North America. De Soto believed the stories of riches. From 1540 to 1543, he traveled through what is now Florida, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. These areas would later become home to the Choctaw.

De Soto had a very strong army. But as his expedition became known for its harshness, the ancestors of the Choctaw fought back. The Battle of Mabila was a major event. Chief Tuskaloosa set up an ambush. This battle greatly weakened de Soto's journey, and his army never fully recovered.

Hernando de Soto, leading his well-equipped Spanish fortune hunters, made contact with the Choctaws in the year 1540. He had been one of a triumvirate which wrecked and plundered the Inca empire and, as a result, was one of the wealthiest men of his time. His invading army lacked nothing in equipage. In true conquistador style, he took as hostage a chief named Chief Tuskaloosa, demanding of him carriers and women. The carriers he got at once. The women, Tuscaloosa said, would be waiting in Mabila (Mobile). The chief neglected to mention that he had also summoned his warriors to be waiting in Mabila. On October 18, 1540, de Soto entered the town and received a gracious welcome. The Choctaws feasted with him, danced for him, then attacked him.

—Bob Ferguson-Choctaw Chronology

The Choctaw Nation Forms

How the Choctaw People Emerged

Not much is known about the time between 1567 and 1699. Many Mississippian settlements were left empty before the 1600s. But similar pottery and burial styles suggest how the Choctaw society came to be.

Some experts believe that people from the Bottle Creek Indian Mounds in Alabama moved west. They joined with groups from the collapsed Moundville chiefdom. These groups were facing a big drop in population. They also joined with the Plaquemine people and "prairie people." Over several generations, these different groups came together. They formed a new society known as the Choctaw.

Other scholars note that Choctaw oral history tells of a long journey. They migrated to Mississippi from west of the Mississippi River.

In 1718, the French renamed Bulbancha to New Orleans. Bulbancha means "place of many tongues" in the Choctaw language.

Sacred Homeland and Origin Stories

Historians believe the Choctaw did not exist as one unified culture before the 1600s. Instead, different groups from Mississippian cultures came together to form the Choctaw people. The Choctaw homeland was in Mississippi. It included Nanih Waiya, a sacred earthwork mound. This area was mostly empty during the Mississippian period.

Nanih Waiya mound remained a very important place. From the 1600s on, the Choctaw lived in this area. They honored Nanih Waiya as the place where their people began. Their stories tell of migrating to this site from west of the great river, believed to be the Mississippi River.

An early European writer, Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz, wrote about the Choctaw origin story in 1758. He said they told him they "had come out from under the earth." This was likely a way to explain their sudden appearance.

A people who by many peculiar customs, are very different from the other red men on the continent ... they are the Chactaws [sic], more commonly known by the name of the Flatheads. These people are the only nation from whom I [sic] could learn any idea of a traditional account of a first origin; and that is their coming out of a hole in the ground, which they shew between their nation and the Chicsaws [sic]; they tell us also that their neighbours were surprised at seeing a people rise at once out of the earth.

—Bernard Romans- Natural History of East and West Florida

Later Choctaw storytellers in the 1800s said the Choctaw people came from either Nanih Waiya mound or a cave. Another story tells of their migration from the west. Their leader used a sacred red pole to guide them.

The Choctaws, a great many winters ago, commenced moving from the country where they then lived, which was a great distance to the west of the great river and the mountains of snow, and they were a great many years on their way. A great medicine man led them the whole way, by going before with a red pole, which he stuck in the ground every night where they encamped. This pole was every morning found leaning to the east, and he told them that they must continue to travel to the east until the pole would stand upright in their encampment, and that there the Great Spirit had directed that they should live.

—George Catlin- Smithsonian Report

French Colonization and Alliances (1682)

In 1682, La Salle was the first French explorer to travel along the Mississippi River. He did not meet the Choctaw directly. But his expedition showed the English that France was serious about settling the South.

The first direct meeting between the Choctaw and the French was in 1699. This was with Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville. The Choctaw probably had indirect contact with English traders before this. The Choctaw and other tribes formed friendships with French settlers in New France and Louisiana. The Choctaw mainly allied with the French. This was to protect themselves from slave raids by tribes allied with English colonists.

The Choctaw developed three main political areas. During the colonial period, these areas sometimes allied with different European traders. This depended on who was closest: French, Spanish, or English. These divisions also showed up during and after the American Revolutionary War. Each area had a main chief and smaller chiefs for each town. The chiefs met on a National Council.

Before the Seven Years' War, the French were the main trading partners for the Choctaw. The British had settled along the Atlantic Coast. Trade disagreements between the eastern and western Choctaw led to the Choctaw Civil War. This war was fought from 1747 to 1750. The pro-French eastern division won.

After losing the Seven Years' War, France gave its land east of the Mississippi River to Britain. From 1763 to 1781, Britain was the Choctaw's main European trading partner. Spanish forces were in New Orleans after taking over French land west of the Mississippi. Some western Choctaw traded with them. Spain declared war on Britain in 1779 during the American Revolution.

Relations with the United States

American Revolutionary War

During the American Revolution, some Choctaw groups supported Britain, while others supported Spain. Some Choctaw warriors helped the British defend Mobile, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida. Chief Franchimastabé led a Choctaw war party with British forces against American rebels in Natchez.

Other Choctaw groups joined George Washington's army. They served throughout the war. A historian noted that "Choctaw scouts served under Washington, Morgan, Wayne and Sullivan."

More than 1,000 Choctaw fought for Britain. They mostly fought against Spain's campaigns along the Gulf Coast. At the same time, many Choctaw helped Spain.

After the American Revolution

After the Revolution, Chief Franchimastabé went to Savannah, Georgia, to get American trade. In the next few years, some Choctaw scouts helped U.S. General Anthony Wayne in the Northwest Indian War.

President George Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox wanted Native Americans to adopt European-American ways of life. Washington believed Native American society was different from European-American society. But he saw the Choctaw and other Five Civilized Tribes as equals. This was a rare view for leaders at that time. He created a plan to encourage "civilizing" Native Americans. Thomas Jefferson continued this plan.

Historian Robert Remini wrote that they believed "once the Indians adopted the practice of private property, built homes, farmed, educated their children, and embraced Christianity, these Native Americans would win acceptance from white Americans."

Washington's plan had six points:

- Fair treatment for Indians.

- Regulated buying of Indian lands.

- Promotion of trade.

- Encouraging experiments to improve Indian society.

- Presidential power to give gifts.

- Punishing those who violated Indian rights.

The government sent agents, like Benjamin Hawkins, to live among the Southeast Indians. These agents taught them how to live like white settlers. Hawkins lived among the Choctaw for almost 30 years. He married Lavinia Downs, a Choctaw woman.

The Choctaw had a matrilineal system. This meant property and leadership passed through the mother's family. Children were part of their mother's family and clan. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, many Scots-Irish traders lived among the Choctaw. They married high-status Choctaw women. Choctaw chiefs saw these marriages as smart alliances. They helped build stronger ties with Americans. The children of these marriages were Choctaw first. Some sons went to Anglo-American schools. They became important interpreters and negotiators for the Choctaw.

Whereas it hath at this time become peculiarly necessary to warn the citizens of the United States against a violation of the treaties made at Hopewell, on the Keowee, on the 28th day of November, 1785, and on the 3d and 10th days of January, 1786, between the United States and the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw nations of Indians ... I do by these presents require, all officers of the United States, as well civil as military, and all other citizens and inhabitants thereof, to govern themselves according to the treaties and act aforesaid, as they will answer the contrary at their peril.

—George Washington, Proclamation Regarding Treaties, Regarding Treaties with the Cherokee, Choctaw and Chickasaw, 1790.

Hopewell Treaty (1786)

In October 1785, Taboca, a Choctaw chief, led over 125 Choctaws to the Keowee River. This is near what is now Hopewell, South Carolina. After two months of travel, they met with U.S. representatives. They performed complex Choctaw ceremonies. One was the eagle tail dance. The Choctaw explained that the bald eagle is a symbol of peace. Choctaw women painted in white adopted the American commissioners as family. Smoking pipes sealed the agreements between the two nations.

After the rituals, the Choctaw asked John Woods to live with them. This would help improve communication with the U.S. In return, Taboca was allowed to visit the United States Congress. On January 3, 1786, the Treaty of Hopewell was signed. Article 11 stated that "the hatchet shall be forever buried." It also said peace and friendship would be re-established between the U.S. and the Choctaw nation.

The treaty required the Choctaw to return escaped enslaved Africans to colonists. They also had to turn over any Choctaw convicted of crimes by the U.S. It set borders between the U.S. and the Choctaw Nation. And it required returning any property taken from colonists during the Revolutionary War.

In the early 1800s, President Thomas Jefferson considered a Choctaw idea. They wanted to sell land to the United States to pay off debts to traders.

We have long heard of your nation as a numerous, peaceable, and friendly people; but this is the first visit we have had from its great men at the seat of our government. I welcome you here; am glad to take you by the hand, and to assure you, for your nation, that we are their friends. Born in the same land, we ought to live as brothers, doing to each other all the good we can, and not listening to wicked men, who may endeavor to make us enemies ... It is at the request which you sent me in September, signed by Puckshanublee and other chiefs, and which you now repeat, that I listen to your proposition to sell us lands. You say you owe a great debt to your merchants, that you have nothing to pay it with but lands, and you pray us to take lands, and pay your debt. The sum you have occasion for, brothers, is a very great one. We have never yet paid as much to any of our red brethren for the purchase of lands ...

—President Thomas Jefferson, Brothers of the Choctaw Nation, December 17, 1803

After the Revolutionary War, the Choctaw did not want to ally with countries against the United States. Historian John Swanton noted that "the Choctaw were never at war with the Americans." A few joined the hostile Creeks due to Tecumseh's influence. But the Choctaw Nation as a whole stayed out of anti-American alliances. This was thanks to the influence of Apushmataha, a great Choctaw chief.

War of 1812

In 1811, the Shawnee leader Tecumseh tried to unite Indian tribes. He wanted to expel U.S. settlers from the Northwest. Tecumseh met with Choctaw leaders to convince them to join. But Pushmataha, a very important Choctaw leader, spoke against Tecumseh. Pushmataha was chief for the Six Towns district. He argued that the Choctaw and Chickasaw had always lived peacefully with European Americans. They had learned valuable skills and traded fairly. The Choctaw-Chickasaw council voted against allying with Tecumseh. Pushmataha warned Tecumseh that he would fight against those who fought the United States.

Before the War of 1812, Louisiana Governor William C. C. Claiborne asked the Choctaws to stay out of the "white man's war." But the Choctaw did get involved. Pushmataha led the Choctaw in alliance with the U.S. He argued against the Creek Red Sticks' alliance with Britain. Pushmataha traveled to St. Stephens, Alabama, in 1813. He offered an alliance with U.S. forces and recruited Choctaw warriors.

Pushmataha raised a company of 125 Choctaw warriors. He was made a lieutenant colonel or brigadier general in the United States Army. He joined the U.S. Army under General Ferdinand Claiborne. About 125 Choctaw warriors helped attack Creek forces in December 1813. After this victory, more Choctaw volunteered. By February 1814, Pushmataha commanded a larger Choctaw force. They joined General Andrew Jackson to clear Creek territories near Pensacola, Florida. After the Creek were defeated at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814, many Choctaw left.

At the Battle of New Orleans, only a small group of Choctaw and Chickasaw warriors remained with Jackson. A mixed-ancestry warrior named Pierre Juzan led a group of Choctaw warriors. They supported Andrew Jackson and ambushed British forces. The Choctaw warriors were described as lurking "way out in the swamp, basking on logs, like so many alligators." One notable Choctaw warrior, Poindexter, killed five British sentries over three nights.

Doak's Stand Treaty (1820)

In October 1820, Andrew Jackson and Thomas Hinds met with Choctaw chiefs. They met at Doak's Stand on the Natchez Trace. The U.S. wanted the Choctaw to give up part of their land in Mississippi.

Finally Jackson resorted to threats and a temper tantrum to gain their consent. He warned them of the loss of American friendship; he promised to wage war against them and destroy the Nation; finally he shouted his determination to remove them whether they liked it or not.

—Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson

The meeting began on October 10. Jackson, known as "Sharp Knife," spoke to over 500 Choctaws. Pushmataha accused Jackson of lying about the land west of the Mississippi. Pushmataha said, "I know the country well ... The grass is everywhere very short ... There are but few beavers, and the honey and fruit are rare things." Jackson then used threats. This pressured the Choctaws to sign the Doak's Stand treaty. Pushmataha continued to argue about the treaty terms. He stated that "no alteration shall be made in the boundaries ... until the Choctaw people are sufficiently progressed in the arts of civilization to become citizens of the States." Jackson agreed to this. On October 18, the Treaty of Doak's Stand was signed.

Article 4 of the treaty prepared Choctaws to become U.S. citizens. It said they would become "civilized." This article later influenced Article 14 in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.

ARTICLE 4. The boundaries hereby established between the Choctaw Indians and the United States, on this side of the Mississippi river, shall remain without alteration until the period at which said nation shall become so civilized and enlightened as to be made citizens of the United States ...

—Treaty with the Choctaw, 1820

Negotiations with the U.S. Government (1820s)

Apuckshunubbee, Pushmataha, and Mosholatubbee were the main chiefs of the three Choctaw divisions. They led a group to Washington City (now Washington, D.C.). They wanted to discuss problems with European Americans settling on Choctaw lands. They wanted the settlers removed or money for the land. The group included other important Choctaw leaders and the U.S. interpreter, Major John Pitchlynn. Apuckshunubbee died in Maysville, Kentucky, before reaching Washington.

Pushmataha met with President James Monroe. He gave a speech to Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. He reminded them of the long friendship between the U.S. and the Choctaw. He said, "I can say and tell the truth that no Choctaw ever drew his bow against the United States ... My nation has given of their country until it is very small. We are in trouble." On January 20, 1825, Choctaw chiefs signed the Treaty of Washington City. This gave more land to the United States.

Pushmataha died in Washington from a lung illness. He was given full U.S. military burial honors.

The deaths of these two strong leaders were a big loss for the Choctaw Nation. But younger leaders were emerging. Some were educated in European-American schools. They helped the culture adapt. The Choctaw faced constant pressure to give up their lands. They continued to adopt useful European practices and accepted missionaries. They hoped to be accepted by the Mississippi and national governments. In 1825, the National Council approved starting the Choctaw Academy. This school would educate young Choctaw men. It was established in Kentucky. In 1842, it moved to the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory.

When Andrew Jackson became president in 1828, many Choctaw realized that moving was unavoidable. They kept adopting European practices. But they faced Jackson's and settlers' strong pressure to give up their lands.

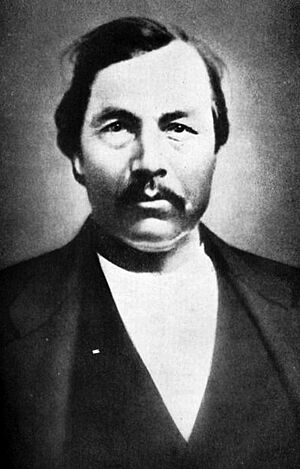

The 1830 Election and Treaty

In March 1830, the division chiefs resigned. The National Council elected Greenwood LeFlore as Principal Chief. He was to negotiate with the U.S. government. This was the first time such a position was authorized. LeFlore believed removal was inevitable. He hoped to protect rights for Choctaw people in Indian Territory and Mississippi. He wrote a treaty and sent it to Washington, D.C. There was much disagreement among the Choctaw. Some thought they could resist moving. But the chiefs agreed they could not fight back with weapons.

Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830)

At Andrew Jackson's request, the U.S. Congress debated an Indian Removal Bill. It passed by a very close vote. Jackson signed it into law on June 30, 1830. He then focused on the Choctaw in Mississippi.

To the voters of Mississippi. Fellow Citizens:-I have fought for you, I have been by your own act, made a citizen of your state; ... According to your laws I am an American citizen, ... I have always battled on the side of this republic ... I have been told by my white brethren, that the pen of history is impartial, and that in after years, our forlorn kindred will have justice and "mercy too" ... I wish you would elect me a member to the next Congress of the [United] States.

—Mushulatubba, Christian Mirror and N.H. Observer, July 1830.

On August 25, 1830, the Choctaw were supposed to meet Jackson in Tennessee. But Greenwood LeFlore told the Secretary of War that his warriors strongly opposed going. President Jackson was angry. But he sent Secretary of War Eaton and John Coffee to meet the Choctaws in their nation. They met at Dancing Rabbit Creek in Mississippi.

Say to them as friends and brothers to listen [to] the voice of their father, & friend. Where [they] now are, they and my white children are too near each other to live in harmony & peace ... It is their white brothers and my wishes for them to remove beyond the Mississippi, it [contains] the [best] advice to both the Choctaws and Chickasaws, whose happiness ... will certainly be promoted by removing ... There ... their children can live upon [it as] long as grass grows or water runs ... It shall be theirs forever ... and all who wish to remain as citizens [shall have] reservations laid out to cover [their improv]ements; and the justice due [from a] father to his red children will [be awarded to] them. [Again I] beg you, tell them to listen. [The plan proposed] is the only one by which [they can be] perpetuated as a nation ... I am very respectfully your friend, & the friend of my Choctaw and Chickasaw brethren. Andrew Jackson.

—Andrew Jackson to the Choctaw & Chickasaw Nations, 1829.

The commissioners met with the chiefs on September 15, 1830. About 6,000 Choctaw men, women, and children were there. The U.S. explained the removal policy. The Choctaws had to choose: move or become U.S. citizens under U.S. law. The treaty required them to give up their remaining homeland. But one part of the treaty made removal more acceptable.

ART. XIV. Each Choctaw head of a family being desirous to remain and become a citizen of the States, shall be permitted to do so, by signifying his intention to the Agent within six months from the ratification of this Treaty, and he or she shall thereupon be entitled to a reservation of one section of six hundred and forty acres of land ...

—Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, 1830

On September 27, 1830, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was signed. This was one of the largest land transfers between the U.S. and Native Americans not caused by war. The Choctaw gave up their traditional lands. This opened them up for European-American settlement. Article 14 allowed some Choctaw to stay in Mississippi. About 1,300 Choctaws chose to do so. They were one of the first major non-European groups to become U.S. citizens. Article 22 tried to put a Choctaw representative in the U.S. House of Representatives.

At this time, the Choctaw split into two groups. These were the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. The Oklahoma nation kept its self-governance. But the tribe in Mississippi followed state and federal laws.

The Removal Era

After giving up about 11 million acres (45,000 km2), the Choctaw moved in three stages. The first was in fall 1831, the second in 1832, and the last in 1833. Nearly 15,000 Choctaws moved to what would be called Indian Territory (later Oklahoma). About 2,500 died along the way. This journey became known as the Trail of Tears. The treaty was approved on February 25, 1831. President Jackson wanted it to be a model for future removals. Principal Chief George W. Harkins wrote a farewell letter to the American people. It was widely published.

It is with considerable diffidence that I attempt to address the American people, knowing and feeling sensibly my incompetency; and believing that your highly and well improved minds would not be well entertained by the address of a Choctaw ... We as Choctaws rather chose to suffer and be free ...

—George W. Harkins, George W. Harkins to the American People

Alexis de Tocqueville, a French thinker, saw the Choctaw removals in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1831.

In the whole scene there was an air of ruin and destruction, something which betrayed a final and irrevocable adieu; one couldn't watch without feeling one's heart wrung. The Indians were tranquil, but sombre and taciturn. There was one who could speak English and of whom I asked why the Chactas were leaving their country. "To be free," he answered, could never get any other reason out of him. We ... watch the expulsion ... of one of the most celebrated and ancient American peoples.

—Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America

About 4,000–6,000 Choctaw stayed in Mississippi after the first removals. The U.S. agent, William Ward, was against their treaty rights. Although many Choctaw stayed, only 143 families received land under the treaty. For the next ten years, the Choctaws in Mississippi faced increasing legal problems and threats. Removals continued throughout the 1800s and 1900s. In 1846, 1,000 Choctaw moved. In 1903, another 300 Mississippi Choctaw were persuaded to move to Oklahoma. By 1930, only 1,665 remained in Mississippi.

I do certify that the foregoing persons did apply to me as agent to have their names registered to remain five years and become citizens of the States before the 24th (August) 1831.

—William Ward, 1831, Col. William Wards Register

Pre-Civil War (1840)

Choctaw chief Greenwood LeFlore stayed in Mississippi after the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. He became a U.S. citizen and a successful businessman. He was elected as a Mississippi state representative and senator. He was a prominent figure in Mississippi society and a friend of Jefferson Davis.

During the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849), the Choctaw agency in Arkansas raised $170. They sent it to help starving Irish people. The Arkansas Intelligencer reported that "all subscribed, agents, missionaries, traders and Indians, a considerable portion of which fund was made up by the latter."

It had been just 16 years since the Choctaw people had experienced the Trail of Tears, and they had faced starvation ... It was an amazing gesture. By today's standards, it might be a million dollars", according to Judy Allen, editor of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma's newspaper, Bishinik, based at the Oklahoma Choctaw tribal headquarters in Durant, Oklahoma.

To honor this, eight Irish people retraced the Trail of Tears 150 years later. In the late 1900s, Irish President Mary Robinson praised the donation. On June 18, 2017, the Kindred Spirits memorial was unveiled in Midleton, Ireland. It is a circle of steel feathers. A Choctaw group, including Chief Gary Batton, attended the ceremony. On March 12, 2018, the Irish Prime Minister announced a scholarship program. It allows Choctaw students to study in Ireland. In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, an Irish charity raised over $1.8 million. This was to support the struggling Navajo and Hopi Nations. It was a repayment for the Choctaws' donation long ago.

For the Choctaw who stayed in Mississippi after 1855, life became harder. Many lost their lands and money to dishonest white people. Mississippi refused to let the Choctaw participate in government. Most were isolated because they spoke little English. This made it hard to work in mainstream society. Also, European Americans classified them as free people of color. This meant they were excluded from segregated white schools. The state had no public schools until after the Reconstruction era.

Choctaws ... were at the mercy of the whites who could commit crimes against them without fear of the law. Even black slaves had more legal rights than did the Choctaws during this period.

—Charles Hudson- The Southeastern Indians

1853 World's Fair

In May 1853, Choctaws traveled from Mobile, Alabama, to Boston and New York. They were going to participate in America's first world's fair. This was the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations.

CHOCTAW INDIANS FOR THE CRYSTAL PALACE.—Capt. Post, of the schooner J. S. Lane, who arrived on Sunday, from Mobile, states that on the 26th ultimo, off the Great Isaacs, he spoke the brig Pembroke, from, Mobile for New-York, having on board a company of Choctaw Indians, for exhibition at the Crystal Palace.

THE CHOCTAW INDIANS.—Each succeeding performance of these interesting aborigines prove. that they are increasing in popularity with our citizens. Their delineations of the "Great Ball Play," drew down the applauds of the house. They appear this evening and to-morrow, after which they quit Brooklyn, wending their way homewards. The Brooklyn Museum is not half large enough to contain the crowds that flock nightly to its doors. There will be afternoon performances this day and to-morrow, to accommodate the young folks.

CHOCTAW INDIANS.—These wonderful and thrilling Exhibitions are attracting intense interest. The crowds that see them, go away astonished and delighted with valuable information. Among the Company are Hoocha, their chief, aged 58 years; Teschu the Medicine man, aged 58; and Silver smith. This is the greatest opportunity ever given to the New-Yorkers to obtain a full idea of Indian life.

The GREAT BALL PLAY, and the grand exciting WAR DANCE, will be exhibited this Evening, with other Dances and Songs of great interest. At the Assembly Rooms, Broadway, above Howard-st. Doors open at 7. Exercises to commence at 8. Admission 25 cents. Reserved Seats 50 cents.

American Civil War (1861)

- Further information: Choctaw in the American Civil War

Both the Indian Territory and Mississippi Choctaws allied with the Confederate States of America. They signed a treaty in July 1861. This treaty promised the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations their own power. A historian wrote that the "United States abandoned the Choctaws and Chickasaws" when Confederate troops entered their nation. After the Confederacy lost, the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory signed a new treaty in 1866. They gave up the western part of their lands to the United States.

After the Civil War: Reconstruction (1865)

Mississippi Choctaw

From about 1865 to 1914, Mississippi Choctaws were mostly ignored. They received little government, health, or education services. Records about them during this time are few. They had no legal protection. Local white people often threatened them. The Choctaw chose to live separately and continued their traditional culture.

After the Reconstruction era, white state lawmakers passed Jim Crow laws. These laws created legal separation by race. They also prevented most African Americans and Native Americans from voting. The new Mississippi constitution of 1890 changed voting rules to discriminate against both groups. White lawmakers divided society into two groups: white and "colored." They put Mississippi Choctaw and other Native Americans into the "colored" group. This meant the Choctaw faced racial segregation. They were excluded from public places, just like African Americans. The Choctaw were not white, owned little land, and had minimal legal protection.

Most landless men became sharecroppers to earn a living. Women made and sold traditional hand-woven baskets. Choctaw sharecropping decreased after World War II. This was because large farms started using machines.

Choctaw Nation

The Confederacy's loss was also a loss for the Choctaw Nation. Before removal, the Choctaws had interacted with Africans. The wealthiest Choctaw had bought enslaved people. They adopted the practice of slavery, like European Americans, for labor. During this time, enslaved Black people had more legal protection under U.S. law than the Choctaw did. Many Choctaws, including chiefs, owned enslaved people. They took enslaved people with them to Indian Territory. Slavery continued until 1866. After the Civil War, a treaty with the U.S. required them to free the enslaved people in their Nation. Those who chose to stay were offered full citizenship and rights. These former enslaved people were called the Choctaw Freedmen. After much discussion, the Choctaw Nation granted them citizenship in 1885.

In post-war treaties, the U.S. government also gained land in the western part of the territory. They also got rights to build railroads across Indian Territory. Choctaw chief, Allen Wright, suggested Oklahoma as a name for a new territory. Oklahoma means "red man" in Choctaw.

The railroads brought more pressure on the Choctaw Nation. They attracted large mining and timber companies. This increased tribal income. But the railroads also brought many European-American settlers, including new immigrants.

The Curtis Act of 1898 aimed to make Native Americans adopt mainstream American culture. It ended tribal governments and proposed ending communal tribal lands. Instead, land would be given to individual tribal members. The U.S. declared any extra land "surplus." This land was then sold to new European-American settlers. Individual ownership also meant Native Americans could sell their land. The U.S. government set up the Dawes Commission to manage this. It registered tribal members and gave out land.

Starting in 1894, the Dawes Commission registered Choctaw families. This was so tribal lands could be given out. The final list included 18,981 citizens of the Choctaw Nation. It also had 1,639 Mississippi Choctaw and 5,994 former enslaved people (and their descendants). After land was given out, the U.S. wanted to end tribal governments. They wanted to admit the two territories as one state.

Oklahoma Statehood (1889)

After the Civil War, the Five Civilized Tribes had to give up land. This led to the creation of Oklahoma Territory. The government used railroad access to develop the territory. The Indian Appropriations Bill of 1889 allowed President Benjamin Harrison to open two million acres (8,000 km2) of Oklahoma Territory for settlement. This led to the Land Run of 1889. The Choctaw Nation was overwhelmed by new settlers. They could not control their activities.

In 1905, delegates from the Five Civilized Tribes met. They wrote a constitution for an Indian-controlled state. They wanted Indian Territory to become the State of Sequoyah. They took their plan to Washington, D.C. But representatives from eastern states opposed it. They did not want two new western states. President Theodore Roosevelt decided that Oklahoma and Indian territories had to become one state, Oklahoma. To do this, tribal governments had to end. All residents had to accept state government. Many Native American leaders from the Sequoyah Convention joined the new state convention. Oklahoma's constitution was based on many ideas from the State of Sequoyah.

In 1906, the U.S. ended the governments of the Five Civilized Tribes. This was part of ongoing talks about the future. The Choctaw Nation continued to protect resources not covered by treaties. On November 16, 1907, Oklahoma became the 46th state.

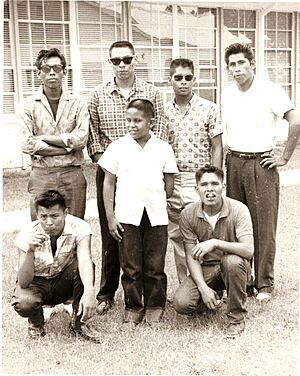

Mississippi Choctaw Delegation to Washington (1914)

By 1907, the Mississippi Choctaw were in danger of disappearing. The Dawes Commission had sent many to Indian Territory. Only 1,253 members remained. Meetings were held in 1913 to find a solution. Wesley Johnson was elected chief of the new Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana Choctaw Council. The council chose delegates to send to Washington, D.C. They wanted to bring attention to their difficult situation.

Historian Robert Bruce Ferguson wrote that in January 1914, Chief Wesley Johnson and his delegates traveled to Washington, D.C. They met with many senators and representatives. They convinced federal officials to bring the Choctaw case to Congress. On February 5th, they met President Woodrow Wilson. Culbertson Davis gave a beaded Choctaw belt to the President as a sign of friendship.

Almost two years after the trip, the Indian Appropriations Act of May 18, 1916, was passed. It allowed $1,000 for an investigation into the Mississippi Choctaws' condition. John R. T. Reeves was to "investigate the condition of the Indians living in Mississippi." He was to report on their needs for land and schools. Reeves submitted his report on November 6, 1916.

Hearing at Union, Mississippi

In March 1917, federal representatives held hearings. About 100 Choctaws attended. They discussed the needs of the Mississippi Choctaws. These hearings led to improvements. These included better access to health care, housing, and schools.

After Cato H. Sells investigated, the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) started the Choctaw Agency. This was on October 8, 1918. The agency was in Philadelphia, Mississippi, a center of Indian activity. Dr. Frank J. McKinley was its first superintendent and doctor.

Before 1916, six Indian schools operated in three counties. The agency established new schools in several Indian communities. Under segregation, few schools were open to Choctaw children. White southerners classified them as non-whites.

Improvements for the Mississippi Choctaws were slowed by world events. World War I shifted Washington's focus to the war. Some Mississippi Choctaws served in the war. The Spanish Flu also slowed progress. Many Choctaws died from the worldwide epidemic.

World War I (1918)

In the last days of World War I, a group of Oklahoma Choctaws served in the U.S. Army. They used their native language for secret communication. Germans could not understand it. These men are now called the Choctaw Code Talkers. Captain Lawrence heard Solomon Louis and Mitchell Bobb speaking Choctaw. He learned there were eight Choctaw men in the battalion.

Fourteen Choctaw men in the Army's 36th Division learned to use their language for military messages. Their communications helped the American army win key battles in France. Within 24 hours of using the Choctaw speakers, the U.S. Army gained control of their communications. In less than 72 hours, the Germans were retreating. The 14 Choctaw Code Talkers were: Albert Billy, Mitchell Bobb, Victor Brown, Ben Caterby, James Edwards, Tobias Frazer, Ben Hampton, Solomon Louis, Pete Maytubby, Jeff Nelson, Joseph Oklahombi, Robert Taylor, Calvin Wilson, and Captain Walter Veach.

It took over 70 years for the Choctaw Code Talkers to be fully recognized. On November 3, 1989, the French government honored them. They received the Chevalier de L'Ordre National du Mérite (Knight of the National Order of Merit).

The U.S. Army used Choctaw speakers again for coded language during World War II.

Reorganization (1934)

During the Great Depression and the Roosevelt Administration, new programs helped the South. A 1933 report described the poor conditions of Mississippi Choctaws. Their population had grown slightly to 1,665 people by 1930. John Collier, the U.S. Commissioner for Indian Affairs, used this report. He used it to support reorganizing the Mississippi Choctaw. This helped them form their own tribal government. It also gave them a better relationship with the federal government.

In 1934, President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Indian Reorganization Act. This law was very important for the survival of the Mississippi Choctaw. Baxter York, Emmett York, and Joe Chitto worked to gain recognition for the Choctaw. They realized that adopting a constitution was the only way. A rival group, the Mississippi Choctaw Indian Federation, opposed tribal recognition. They feared control by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). They later disbanded. The first Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians tribal council members were Baxter and Emmett York. Joe Chitto was the first chairperson.

With the tribe's new government, the Secretary of the Interior declared that 18,000 acres (73 km2) would be held in trust for the Choctaw of Mississippi. Land in Neshoba and nearby counties became a federal Indian reservation. Eight communities were included: Bogue Chitto, Bogue Homa, Conehatta, Crystal Ridge, Pearl River, Red Water, Tucker, and Standing Pine.

Under the Indian Reorganization Act, the Mississippi Choctaws reorganized on April 20, 1945. They became the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. This gave them some independence from the state government. The state still enforced racial segregation and discrimination.

World War II (1941)

World War II was a big turning point for Choctaws and Native Americans. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek said Mississippi Choctaws had U.S. citizenship. But they were seen as "colored people" in a state with Jim Crow laws. State services for Native Americans did not exist. The state was poor and relied on farming. Services for minorities were always underfunded. The state constitution and voting rules kept most Native Americans from voting. This meant they could not serve on juries or run for office. They had no political voice.

A Mississippi Choctaw veteran said, "Indians were not supposed to go in the military back then ... the military was mainly for whites. My category was white instead of Indian. I don't know why they did that. Even though Indians weren't citizens of this country, couldn't register to vote, didn't have a draft card or anything, they took us anyway."

Van Barfoot, a Choctaw from Mississippi, was a sergeant in the U.S. Army. He received the Medal of Honor. Barfoot was promoted to second lieutenant. He destroyed two German machine gun nests, captured 17 prisoners, and disabled an enemy tank. Lt. Colonel Edward E. McClish from Oklahoma was a guerrilla leader in the Philippines.

After Reorganization

The first Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians tribal council meeting was on July 10, 1945. The members included Joe Chitto (Chairman), J.C. Allen (Vice Chairman), and Nicholas Bell (Secretary Treasurer).

After World War II, Congress wanted to reduce federal power over Native American lands. In 1953, the House passed Resolution 108. It proposed ending federal services for 13 tribes. That same year, Public Law 280 gave states power over tribal lands in five states. Within ten years, Congress ended federal services for over sixty groups. This was despite strong opposition from Native Americans. Congress decided to end tribes' federal status quickly. The government also created programs to move Native Americans to cities. This was to help them find jobs. In 1959, the Choctaw Termination Act was passed. The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma would lose its status as a self-governing nation by August 25, 1970.

President John F. Kennedy stopped further terminations in 1961. Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon later rejected the policy of ending federal relationships with Native American tribes.

We must affirm the right of the first Americans to remain Indians while exercising their rights as Americans. We must affirm their right to freedom of choice and self-determination. We must seek new ways to provide Federal assistance to Indians-with new emphasis on Indian self-help and with respect for Indian culture. And we must assure the Indian people that it is our desire and intention that the special relationship between the Indian and his government grow and flourish. For, the first among us must be not be last.

—President Lyndon Johnson, Message to Congress "The Forgotten American", March 6, 1968.

Mississippi Choctaw Self-Determination Era

The Choctaw people continued to struggle economically. This was due to prejudice, cultural isolation, and lack of jobs. The Choctaw, who for 150 years were seen as neither white nor black, remained in poverty.

The civil rights movement brought big changes for the Choctaw in Mississippi. Their civil rights were improved. Before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, most jobs went to whites, then blacks. The end of legal racial segregation allowed the Choctaws to use public places and services. These had been only for white people before.

Phillip Martin served in the U.S. Army in Europe during World War II. He returned to his home in Neshoba County, Mississippi. After seeing his people's poverty, he decided to stay and help. Martin served as chairperson in various Choctaw committees until 1977.

Martin was elected as Chief of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. He served for 30 years, being re-elected until 2007. Martin died in Jackson, Mississippi, on February 4, 2010. He was remembered as a visionary leader. He lifted his people out of poverty with businesses and casinos built on tribal land.

Modern Choctaw History

From the 1960s to Today

During the civil rights era, between 1965 and 1982, many Choctaw Native Americans renewed their commitment to their heritage. They worked to celebrate their strengths and use their rights. This reversed the trend of abandoning Indian culture. In the 1960s, Community Action programs for Native Americans focused on citizen participation. In the 1970s, the Choctaw rejected extreme Indian activism. The Oklahoma Choctaw sought local solutions to regain their cultural identity and self-governance. The Mississippi Choctaw started new businesses.

Federal policy under President Richard M. Nixon encouraged tribes to have more self-determination. He ended the federal policy of ending tribes' recognized status.

Forced termination is wrong, in my judgment, for a number of reasons. First, the premises on which it rests are wrong ... The second reason for rejecting forced termination is that the practical results have been clearly harmful in the few instances in which termination actually has been tried ... The third argument I would make against forced termination concerns the effect it has had upon the overwhelming majority of tribes which still enjoy a special relationship with the Federal government ... The recommendations of this administration represent an historic step forward in Indian policy. We are proposing to break sharply with past approaches to Indian problems.

—President Richard Nixon, Special Message on Indian Affairs, July 8, 1970.

Soon after, Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This law allowed tribes to negotiate contracts with the BIA. They could directly manage more of their education and social service programs. It also gave grants to help tribes plan for this responsibility. It also allowed Indian parents to be on local school boards.

Starting in 1979, the Mississippi Choctaw tribal council worked on economic development. They first aimed to attract industries to the reservation. They had many people available to work, natural resources, and no state or federal taxes. Industries have included car parts, greeting cards, and plastic molding. The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians is one of the state's largest employers. They run 19 businesses and employ 7,800 people.

Starting with New Hampshire in 1963, many states began operating lotteries and other gambling. This was to raise money for government services. In 1987, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that federally recognized tribes could operate gaming facilities on reservations. This was because reservations are sovereign territory, free from state rules. As tribes started developing gambling, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) in 1988. It set rules for Native American tribes to operate casinos. They could only do so in states that already allowed private gambling. Since then, casino gaming has been a main source of new income for many tribes.

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma developed gaming operations and resorts. The Choctaw Casino Resort and Choctaw Casino Bingo are popular gaming spots in Durant. They are near the Oklahoma-Texas border. They attract people from Southern Oklahoma and North Texas.

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (MBCI) tried to get state agreement for gaming. But in 1992, Mississippi Governor Kirk Fordice allowed the MBCI to develop Class III gaming. They have built one of the largest casino resorts in the nation. It is in Philadelphia, Mississippi, near the Pearl River. The Silver Star Casino opened in 1994. The Golden Moon Casino opened in 2002. These casinos are known as the Pearl River Resort.

After almost 200 years, the Choctaw have regained control of the ancient sacred site of Nanih Waiya. Mississippi protected the site as a state park for years. In 2006, the state legislature passed a bill to return Nanih Waiya to the Choctaw.

State-Recognized Tribes

Two U.S. states recognize tribes that the federal government does not.

Alabama recognizes the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians. They have a 600-acre reservation in southwestern Alabama. They have about 3,600 enrolled members. This group is closely linked to Calcedeaver Elementary School.

Louisiana recognizes the Choctaw-Apache Tribe of Ebarb, Clifton Choctaw, and Louisiana Choctaw Tribe.

Choctaw Population History

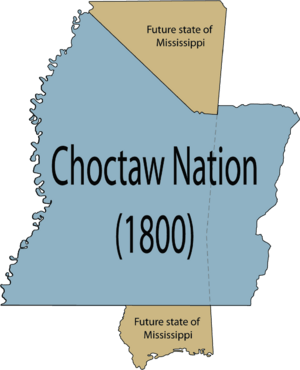

Early estimates suggest the Choctaw population may have been as high as 125,000 people in 1718. Other estimates from that time were lower. But they might have only counted part of the tribe. In 1775, one estimate put the Choctaw at 10,000 warriors, meaning about 50,000 people. Around 1800, they were estimated at 30,000 people. In 1820, before the Trail of Tears, the Choctaw were estimated at 25,000 people. A report from 1841 showed that 15,177 Choctaws had moved to Oklahoma. And 3,323 stayed in the east.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the Choctaw population has grown. In 2020, they numbered 254,154.

In the 2010 U.S. Census, people identifying as Choctaw lived in every state. The states with the largest Choctaw populations were:

- Oklahoma – 79,006

- Texas – 24,024

- California – 23,403

- Mississippi – 9,260

- Arkansas – 4,840

- Alabama – 4,513