Isobel Wylie Hutchison facts for kids

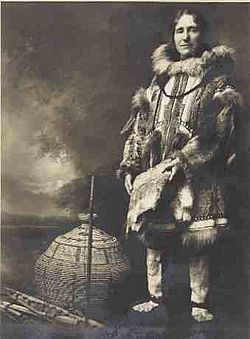

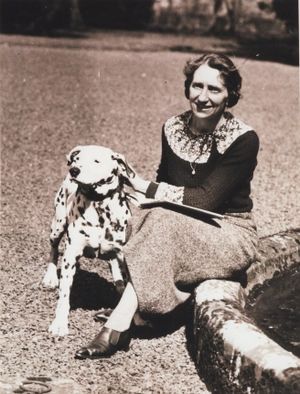

Isobel Wylie Hutchison (born May 30, 1889 – died February 20, 1982) was a brave Scottish explorer, filmmaker, and botanist. She loved to travel to cold places like Iceland, Greenland, Alaska, and the Aleutian Islands.

Isobel wrote many poems and books about her adventures. She also wrote articles for famous magazines like National Geographic. She often gave talks, showing her films, photos, and paintings to make her stories come alive.

Many of the plants Isobel collected are now kept in famous gardens like Kew Gardens and the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. In 1934, she became the first woman to win the Mungo Park Medal from the Royal Scottish Geographical Society. Later, in 1949, she received a special award from St. Andrews University. They honored her for her amazing work with plants and her "unbeatable spirit" that helped her face dangers and difficulties.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Isobel's Early Life and Education

Isobel was born at Carlowrie Castle in West Lothian, Scotland. She was the third of five children. Her father passed away when she was only ten years old. However, he made sure all his children had money for their future. This meant Isobel was financially independent throughout her life.

Her grandfather, a successful businessman, spent a lot of time with Isobel. He taught her about plants and gardening, which sparked her interest in botany early on. Isobel also had a private teacher at home. She was very active, enjoying sports like croquet, tennis, and skating. She also loved Scottish country dancing and long walks.

From 1900, she went to school in Edinburgh. She studied subjects that were common for young women of her time. After seeing her sister's husband, a naval officer, often away for long periods, Isobel decided that marriage might limit her own life and adventures.

Isobel loved writing from a young age. She started keeping a diary in 1899 and continued for most of her life. She even edited a family magazine called "The Scribbler." Isobel was also very good with languages. As an adult, she could speak Italian, Gaelic, Greek, Hebrew, Danish, Icelandic, Greenlandic, and some Inuit words.

She enjoyed long walks from her early years. She often walked eight miles from her home to Edinburgh, even though her family had a car. These walks grew longer as she got older, sometimes reaching 100 miles! She later wrote articles about these "strolls" for National Geographic Magazine.

Isobel faced sadness in her family. Her youngest brother, Frank, died in 1912 in a climbing accident. This deeply affected her, and she stopped writing in her diary for a while. Another brother, Walter, was killed in the First World War.

From 1917 to 1918, Isobel studied business, marketing, religion, and languages at Studley Horticultural College for Women. Life at the college was tough during the war, with little food and many men away. Influenza spread, making many students sick. Isobel, who was a bit shy, made lifelong friends there.

Life After the War

After finishing college, Isobel still felt a bit unsure about her path. In 1919, she started studying religious topics at King's College, University of London.

In 1920, after a busy and emotional time, Isobel faced a difficult period with her health. However, her writing continued to be successful. Her poetry was praised, and she started writing a novel. The money she earned from her writing helped her financially.

In 1924, Isobel was invited to travel to Spain, Morocco, Egypt, and Israel with a friend from Edinburgh. She found her friend to be too protective. This made Isobel decide that she would travel alone in the future. She traveled alone or with men later in life, but she never married.

When she returned to Scotland, she spent time walking around islands like Barra and Lewis. She completed a 150-mile hike! She wrote an article about it for National Geographic Magazine, which helped pay for her next big trip to Iceland.

Amazing Arctic Adventures

Exploring Iceland

Isobel first thought of visiting Iceland in 1924. At first, it was just a holiday. She spent about a month in Reykjavik, seeing famous sights like geysers. After hearing a lecture by an explorer, she decided to walk around the entire country!

Local guides thought this was impossible. But one guide finally gave her a route, though she often got lost. However, the people of Iceland were very kind. They helped her by lending her ponies and often refused payment. While she admired the flowers, she wasn't seriously collecting plants on this trip. After returning to Scotland, she wrote another article for National Geographic, which became a big 30-page story.

Adventures in Greenland

Visiting Greenland was harder than Iceland. The Danish government carefully watched who entered the country. But because Isobel had official permission to collect flowers for different organizations, she got a visa easily.

She traveled by sea in July 1927, spending much time on board while exploring the eastern coast. She met and got to know many Greenlanders. She was careful to get along with the Danish officials and their wives. Greenland had a strong Christian community, which Isobel, being a regular churchgoer, joined happily. This meant she often got rides with pastors in their boats to outlying villages. This allowed her to see many old churches and cathedrals. At each stop, she collected flowers and plants to send back home.

When Isobel arrived in Angmagssalik in 1927, it was still a very simple town. She stayed for four days, collecting flowers and visiting a traditional Greenlandic tent home. She bought special thigh-length boots called kamiker to protect herself from biting insects.

Her next visit was to Augpilagtok, where huge cliffs rise from the sea. Isobel was sad to see how poor some Greenlanders were. She gave one woman her last pair of spare socks. She also asked a carver to make a model of a kayak to give him some money. This model is now in the National Museum of Scotland.

When Isobel reached Julianehab, there were no hotels. She stayed with the district manager but ate on the ship. She joined in Scottish country dancing with Greenlanders and other passengers. Scottish whalers had brought this dancing style to Greenland.

Her next stop was Igaliko, where she met Hans Reynolds, a Norwegian scientist. He showed her ruins from the 10th century and parts of a cathedral from 1146. She found over 50 plants there, including some barley. She also visited several Danish settlements near Cape Farewell.

It was not possible to reach Cape Farewell itself. So, Isobel landed at Nanortalik. She stayed with the Danish manager, Mr. Mathieson. He helped her travel to an island of birch trees in an umiak (a type of boat) with six rowers. This five-day journey was one of the best times of her life.

Before leaving Greenland, Isobel met Dr. Knud Rasmussen, who became a good friend. She returned to Scotland on the ship Disko, arriving home on Christmas morning, 1927.

Isobel made many friends in Greenland. Dr. Rasmussen even came to stay at Carlowrie. In April 1928, she got permission to visit western Greenland and spent six months getting ready. In August, she sailed to Disko Island.

There, she met Dr. Morton Porsild, who directed the Arctic Research Station. He gave her advice on what seeds to collect and where to find them. She sent these seeds to the Royal Horticultural Society. She then moved to Umanak, where about ten Danes lived with many local people. She stayed in an empty three-bedroom house, and a housekeeper named Dorthe was found for her. Dorthe later became a close friend. At first, Isobel only spoke Danish, but she soon learned Greenlandic. She collected plants on Nugssuak and also sketched during this trip. Later, she went to Igdlorssuit (Unknown Island) and then to Upernivik, where she stayed in a very simple hut. By this time, she had filled 300 envelopes with seeds! During the winter, she showed films using the projector she had brought.

Isobel brought many books and lent them to her Danish friends. She also brought her steel skates (the locals only had wooden ones) and got a lot of exercise. She regularly went to church with Dorthe and often attended local coffee mornings. Living conditions could be tough, and illnesses like typhoid were common. At one point, her housekeeper Dorthe got sick, and Isobel had to manage everything herself.

Isobel spent seven months in the bay, learning a lot about the local way of life. The dark winter nights were filled with parties and coffee mornings. The winter of 1928 was very harsh, and the temperature dropped very low, freezing the bay solid. Isobel enjoyed fishing through the ice. Her experience even became the subject of a poem.

She was saddened by the harsh realities of Arctic life, where animals sometimes had to be used for survival. By April, there was enough daylight to turn off the constant oil lamps. When the ice began to melt, she could leave Disko Island. She went on tour with the pastor to visit other communities around Umanak Bay, which meant she could look for more plants and flowers. At each community, the pastor held church services, which impressed her greatly. This also became the subject of several poems. She got to know the eight rowers well, as she now spoke Greenlandic fluently. At the end of the trip, she landed on Unknown Island, staying for a month in a small Danish house. This was her happiest time in Greenland. She even said, "I am glad to be alone for a little."

She made several trips in the manager's motorboat to visit other nearby islands for botanical research. From here, Isobel could see the mountain on Nugsuuaq, which she decided to climb. With the help of two local men, she reached the top at 6,250 feet after twelve hours of climbing.

On a cold day in late August 1929, she left Umanak Bay. Her next book, On Greenland’s Closed Shore, was very popular. Over the next two years, she gave many lectures and talks on the BBC, and wrote articles and poems.

Journey to Alaska

Isobel was inspired to go to Alaska after reading a book about the American Arctic. She left Manchester by cargo boat on May 3, 1933. She crossed the Atlantic, went through the Panama Canal, and then traveled up the western coast of America. There were only six passengers, and she traveled quite comfortably.

After a short stop in Vancouver, she traveled up the Inside Passage to Ketchikan. Then she got off the ship at Skagway. From there, she took a train to Whitepass, where she caught a comfortable sternwheeler boat called the Casca down the Yukon. On the ship, she met people who gave her helpful tips about travel and where to spend the winter.

The boat was delayed in Dawson. Always ready to climb mountains, she hiked up the Dome (1,500 feet) with Harry Lester, a police officer she met on the Casca. She also met local botanists who told her which plants to collect and where to find them.

She was advised to send all her luggage to Aklavik. The ship she hoped to catch, the Anyox, had been damaged. She arrived at Fort Yukon at midnight and was met by friends of people she had met on board. She went to Tenana and then Nenana because the next boat was late. Vilhjalmur Stefansson, an Arctic explorer she already knew, told her she needed to fly to Nome to speed up her journey. She had over 360 kilograms (about 800 pounds) of luggage, so the flight cost her $250. She enjoyed the flight, her second ever, but had to land at Nulato overnight before reaching Nome the next day.

In a short time, Isobel made friends with important people in Nome. She ate in local restaurants and gathered much useful information. The repaired Anyox couldn't pick her up at Nome because of very thick ice. There were no other large ships, so she had to stay in Nome for five weeks. She met a local botanist, Charles Thornton, who helped her collect 200 of the 278 local plants.

She also met a Russian trader named Ira Rank, who had a small boat called the Trader. He told her that the journey from Nome to Point Barrow was 500 miles and could take five days if they were lucky. The boat was very small, and Isobel had to share a cabin with Rank. The other two crewmen slept by the engine. Isobel was very adaptable. She was happy to go from traveling in luxury to traveling with three Russians in a cramped and smelly boat. The Trader visited many Eskimo villages along the north coast. They entered the Bering Strait on August 2 but ran into a storm and thick ice. They had to shelter in Prince of Wales Bay for two days. During this time, Isobel went for walks and hunted for plants. Two tin miners fed and entertained them.

The next day was calm, and they reached Point Hope, an old Eskimo village. The people there lived on whales, walrus, and seals. Isobel collected flowers with the local teacher's wife. She also bought some Eskimo artifacts and wished she could have stayed longer.

They sailed past Port Lisburne and on to Cape Lay, then traveled inland through shallow lagoons. Isobel saw her first ice cake here. They anchored by one, but it drifted twelve miles back during the night.

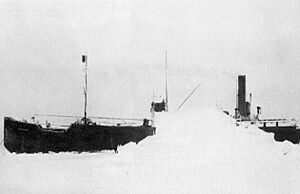

On August 11, they reached Wainwright, one of the largest Eskimo communities where they traded. They heard that the SS Baychimo, a "ghost ship" that had been trapped in ice and abandoned, was sighted only twelve miles away. The men wanted to go and see what they could save.

There was still much useful equipment on it, though Eskimos had already taken some things. The Trader's crew wanted to take the whole ship, but it was too big. So, they only took some valuable items. By this time, Isobel had fully adjusted to life on the Trader and had become friends with the crew.

The Trader slowly moved forward to Singet, which was only 25 miles from Barrow. Here, they stayed in an old Eskimo cabin that Isobel helped Ira Rank clean up. On September 1, a path opened in the ice, and they were able to reach Barrow.

The Trader could not go any further. So, Isobel was introduced to Gus Masik, who had a boat called the Hazel with two Eskimo crew members. After a sad goodbye to the Trader's crew, Isobel left on the Hazel on September 9. They crossed Smith Bay and anchored in fog at Thetis Island. At Beech Point, they met an old friend of Masik's, Aarnout Castel.

Isobel liked Mrs. Castel and talked to her in the kitchen while the men traded goods. They went on to Flaxman Island, where there was a trading post. She went ashore for a walk, enjoying the peace and beauty. The Hazel then crossed Camden Bay, passing Barter Island, and finally arrived at Martin Point on September 15.

There were now only 120 miles to Herschel Island, where Isobel wanted to spend the winter. However, the ice closed in four days later, trapping them for the winter. Isobel had to stay in Masik's one-room hut on Martin Point. She spent the time collecting flowers and having religious discussions with Masik. She wrote down his life story, which she later published.

At the end of October, she visited Tom Gordon, a tall Scotsman who had been a whaling ship captain. He had become a trader after his ship was destroyed by ice. He lived with his native wife and many children in a two-room cabin. Isobel described it as a Scottish-Eskimo home full of interesting people. She stayed there for seven weeks.

On November 3, she set out by sledge with Gus Masik for Herschel Island. They arrived on the fourth day, and Isobel was warmly welcomed by the local agent. The island, eight miles long and four miles wide, was usually busy with ships. But in winter, it only had four white people and two Eskimo families. Masik stayed two more days and then left. Isobel would see him again in Nome and later at her home in Carlowrie. A special police officer, Ethier, and his wife looked after her for two days. Then they arranged for a local guide to take her to Aklavik.

They left on November 10, in very cold weather (-20 degrees Fahrenheit), and arrived at Head Point at four o'clock. The next day, a young Inuk (Eskimo) named Isaac was paid to take her to Shingle Point. It was even colder than the day before, and Isobel had to run behind the sled to stay warm. When she arrived at Shingle Point, three English ladies and Mr. Webster, the Anglican minister, gave her a wonderful meal. There was a school here, and she started to think about how the white teachers were affecting the Eskimos. English was not useful to them when they returned to their families. Also, many illnesses were being brought in, and several Eskimos were sick or had died. She stayed here for thirteen days. On November 23, a group set off for Aklavik. It was so cold that they turned back after two hours. The next day was warmer, and two days later, they reached Aklavik.

Aklavik was a well-established town and the main center for the area. The church and police had bases there, and planes and ships arrived regularly. Isobel joined in the social life. She was a bit of a curiosity as a single woman. To avoid causing offense, she was very careful when writing about her stays with various traders and Eskimos.

She left the town by airplane on February 5. After several flights, she arrived in Winnipeg. From there, she caught the ship Alaunier and returned to Scotland in early March. News of her adventures had already reached Britain. The Times newspaper had reported on her activities on January 10.

Exploring the Aleutian Islands

In the last week of May 1936, Isobel left Scotland for Montreal. From there, she traveled to Winnipeg and finally to Seattle. In Seattle, she caught the ship Yukon for a journey along the coast to Seward. She found that the information she had been given about ships and sailing times in Washington was not always accurate, so she had to be flexible. She had booked a passage on the Starr, but it would be three weeks late. So, she also booked on the Curaçao. This ship took her overnight to Kodiak, Alaska, where she checked into the Sunbeam Hotel. In the two weeks she waited for the Starr to arrive, she explored the area and collected plant samples. The Starr turned out to be a bit messy, and there was limited room in the cabins. However, she met several old friends she had known from her time on the north coast of Alaska.

At Unalaska, she got off the ship, as this was the end of the Starr's journey. She knew she would have to rely on luck to get further west by small fishing and trading boats. She became well known in the area by joining the local church. Luckily, a small schooner called the Penguin was traveling to St. George Island, and she quickly booked a passage. She also managed to get further transport through her friend Commodore Ralf Dempwolf, who arranged for her to travel on a cutter called the Chelan.

She continued her journey on the Penguin to St. Paul Island. There, she collected more plant samples and took films of seals and their groups. She received a radio message that the Chelan could pick her up there. So, she found herself climbing up a rope ladder to get on board. Because of the articles she had written in National Geographic and other respected magazines, she was well-regarded by the navy. Once on board, she was treated very well and given a large cabin to herself. She dined with the officers, and the chef spent a lot of time preparing excellent meals for her. The ship had a duty to inspect Bogoslof Island each year because its shape was always changing. Isobel could not land there due to the rough sea, but she took films of it. They then passed Umnak Island and the Island of the Four Mountains. Their first stop was at At, where the Aleut people had lived for over two thousand years. Besides collecting plants, she was very interested in everything about the inhabitants' way of life. Often, a crew member was assigned to look after Isobel and help her collect samples.

The ship continued west to the island of Amchitka. A submerged mountain range had been discovered here, and the ship needed to map it. The Chelan spent a week charting the waters around this area. The depths varied greatly, and this area had caused several coastguard ships to be lost.

Isobel wanted to land on Attu if possible. For two days, this was impossible. But on the third day, it was safe to anchor, and she went ashore with two sailors. If the weather got worse, they would be left on shore until the ship could return. They worked very hard and found 69 plants.

The people of Attu were very friendly, and Isobel often photographed them. Sadly, years later, the people of Attu faced great hardship when their island was attacked, and many were taken away.

The ship then went on to Kiska, where there was an American naval base. They stayed there for several days, and Isobel was able to climb the mountain south of the harbor. There, she took photos, collected samples, and wrote a poem. The Chelan then sailed back east. She had spent three weeks on board with ninety sailors, traveling a thousand miles in some of the most dangerous seas in the world. The crew was clearly very impressed by her. They even made her an admiral's flag with "Isobel Hutchison, Admiral of the Bering" written on it. When she got back to Alaska, she managed to visit nearly all her old friends and show them photos of her latest adventures.

Later Travels and Activities

Isobel continued traveling for the rest of her life. She recorded many of her trips for National Geographic.

- 1936: Japan, China, Trans-Siberian Railway, Moscow, Poland, Berlin

- 1938: Estonia

- 1946: Denmark

- 1948: A long walk from Carlowrie to London

- 1950: A long walk from Innsbruck to Venice

- 1952: A long walk from Edinburgh to John o' Groats

In the late 1950s, she made only short trips to Europe. She also led a cruise for the National Trust to Fair Isle and St Kilda. By the 1960s, she had mostly stopped traveling far. However, she still cycled over 200 miles from Carlowrie to Bettyhill, riding 40 miles a day!

After the Japanese invasion of Attu Island in 1942, Isobel became a frequent speaker on the BBC. Her home, Carlowrie, was quite run down after being used by the RAF during the war. She needed money for repairs. They didn't even get electricity until 1951.

In her later years, Isobel suffered from arthritis, which eventually made it hard for her to move around. Isobel Wylie Hutchison passed away at her home in Carlowrie on February 20, 1982, at the age of 92. She is buried in the northern cemetery in Kirkliston, alongside her mother and eldest sister.

Awards and Recognition

Isobel Wylie Hutchison was a respected member of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society. She served on its Council from 1936-1940. She was also an honorary editor of the Scottish Geographical Magazine from 1944-1953. Later, she was the RSGS vice president from 1958-1970.

She received the RSGS's Fellowship Diploma in 1932. To her great surprise, she was awarded the Mungo Park Medal on October 24, 1934. She was only the third person and the first woman to receive this important award.

In 1936, she became a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society of London. The University of St Andrews gave her an honorary Doctor of Laws degree in 1949.

Isobel's Legacy

Even though she is not as famous as some male explorers and botanists of her time, Isobel Wylie Hutchison's achievements are truly amazing. She explored widely and mostly on her own. This was at a time when women were not expected to travel far from home. Their accomplishments were often ignored or made to seem less important. One reporter even wrote about her:

"Miss Hutchison is, you feel, much too fragile and gentle for the rigours of Arctic exploration. Dispensing tea in her sunlit sitting room, or sketching the glowing colours of her garden, she seems far more in her correct setting than battling against cold and hardship in half-civilised lands." The Scotsman, November 2, 1939.

Isobel gave over 500 lectures during her lifetime. The plant specimens she collected were sent to famous places like Kew Gardens, the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, and the British Museum.

Her diaries, papers, photographs, films, and other materials are kept in the collections of the National Library of Scotland, the Mitchell Library in Glasgow, and the Royal Scottish Geographical Society. Some of the items she collected are on display in the National Museum of Scotland and the Scott Polar Research Institute (University of Cambridge).

Her life is remembered at Carlowrie Castle, her family home. Isobel Wylie Hutchison is honored with a blue plaque there. Carlowrie Castle also worked with the Royal Scottish Geographical Society to launch "The Isobel Wylie Hutchison Collection" to celebrate her 130th birthday.

Books and Articles by Isobel

Isobel Hutchison wrote six books of poems, seven books about her travels, and twelve articles for National Geographic Magazine.

Poetry Books

- Lyrics from West Lothian. Private publication, 1916

- How Joy was found: A Fantasy in Verse in Five Acts. London: Blackie; New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1917

- The Calling of the Bride. Stirling: E. Mackay, 1926

- The Song of the Bride. London: De La More, 1927

- The Northern Gate. London: De La More, 1927

- Lyrics from Greenland. London: Blackie, 1935

Travel Books

- Original Companions. London: Bodley Head, 1929

- The Eagle's Gift: Alaska Eskimo Tales. New York: Doubleday Doran, 1932

- Flowers and Farming in Greenland. Edinburgh: T. A. Constable, 1930

- On Greenland’s Closed Shore: The Fairyland of the Arctic. Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1930

- North to the Rime-Ringed Sun: Being a Record of an Alaska-Canadian Journey Made in 1933-34. London: Blackie, 1934, 1935; New York: Hillman-Curl, 1937

- With August Masik: Arctic Nights Entertainment: Being the Narrative of an Alaskan Estonian Digger, August Masik, as told to Isobel Wylie Hutchison. Glasgow: Blackie, 1935

- Stepping Stones from Alaska to Asia. London: Blackie, 1937

National Geographic Articles

- "Walking Tour across Iceland", April 1928

- "Riddle of the Aleutians", December 1942

- "Scotland in Wartime", June 1943

- "Wales in Wartime", June 1944

- "Bonnie Scotland, Post-war Style", May 1946

- "2000 Miles through Europe’s Oldest Kingdom", February 1949

- "A Stroll to London", August 1950

- "A Stroll to Venice", September 1951

- "Shetland and Orkney, Britain’s Far North", October 1953

- "From Barra to Butt in the Hebrides", October 1954

- "A Stroll to John o' Groats", July 1956

- "Poets' Voices Linger in Scottish Shrines", October 1957

Isobel also had several other articles published in journals and newspapers.

|

See also

In Spanish: Isobel Wylie Hutchison para niños

In Spanish: Isobel Wylie Hutchison para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |