Kahoʻolawe facts for kids

|

Nickname: The Target Isle

|

|

|---|---|

Landsat satellite image of Kaho‘olawe

|

|

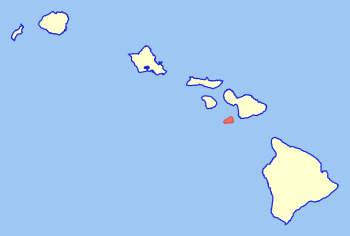

Location in the State of Hawaii

|

|

| Geography | |

| Location | North Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 20°33′N 156°36′W / 20.550°N 156.600°W |

| Area | 44.59 sq mi (115.5 km2) |

| Area rank | 8th largest Hawaiian Island |

| Highest elevation | 1,483 ft (452 m) |

| Highest point | Puʻu Moaulanui |

| Administration | |

|

United States

|

|

| Symbols | |

| Flower | Hinahina kū kahakai (Heliotropium anomalum var. argenteum) |

| Color | ʻĀhinahina (gray) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 (No permanent population) |

| Ethnic groups | Hawaiian |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

Kahoʻolawe (pronounced kah-HO-oh-LAH-vay) is the smallest of the eight main volcanic islands in Hawaii. It is located about 7 miles (11 km) southwest of Maui and southeast of Lānaʻi. Kahoʻolawe is 11 miles (18 km) long and 6 miles (10 km) wide. Its total land area is about 45 square miles (116 square km).

The highest point on Kahoʻolawe is the crater of Lua Makika. It is at the top of Puʻu Moaulanui, which is about 1,477 feet (450 meters) above sea level. Kahoʻolawe is a very dry island. It gets less than 26 inches (65 cm) of rain each year. This is because the island is not tall enough to catch much rain from the trade winds. Also, it sits in the rain shadow of Maui's tall volcano, Haleakalā. Over a quarter of Kahoʻolawe's soil has worn away, especially near the top.

Kahoʻolawe has always had very few people living on it because it lacks fresh water. During World War II and for many years after, the U.S. Armed Forces used it as a training and bombing range. After many years of protests, the U.S. Navy stopped live-fire training in 1990. The entire island was given back to the state of Hawaii in 1994.

The Hawaii State Legislature created the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve. This reserve helps to restore and look after the island and its surrounding waters. Today, Kahoʻolawe can only be used for native Hawaiian cultural, spiritual, and traditional purposes. The U.S. Census Bureau says Kahoʻolawe has no permanent residents.

Contents

The Island's Geology and Formation

Kahoʻolawe is an extinct shield volcano. This means it is a volcano that is no longer active. It formed during the Pleistocene epoch, a long time ago. The island was once connected to a larger island called Maui Nui. It separated about 300,000 years ago.

Most of Kahoʻolawe is covered by basaltic lava flows. A large caldera (a bowl-shaped hollow) is found in the eastern part of the island. The last confirmed volcanic activity on Kahoʻolawe happened about one million years ago. However, some eruptions might have occurred as recently as 10,000 years ago.

Kahoʻolawe's Climate

Kahoʻolawe has a semi-arid climate. This means it is very dry, like a desert, but not quite as extreme.

| Climate data for Kahoʻolawe | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 89 (32) |

92 (33) |

90 (32) |

89 (32) |

90 (32) |

91 (33) |

91 (33) |

92 (33) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

93 (34) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 78.2 (25.7) |

77.9 (25.5) |

78.1 (25.6) |

77.4 (25.2) |

79.3 (26.3) |

78.5 (25.8) |

80.5 (26.9) |

80.9 (27.2) |

81.6 (27.6) |

81.4 (27.4) |

79.6 (26.4) |

78.9 (26.1) |

82.8 (28.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 73.8 (23.2) |

73.6 (23.1) |

73.7 (23.2) |

74.3 (23.5) |

75.9 (24.4) |

75.9 (24.4) |

77.6 (25.3) |

77.6 (25.3) |

77.8 (25.4) |

77.5 (25.3) |

75.8 (24.3) |

74.4 (23.6) |

75.7 (24.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 64.9 (18.3) |

64.8 (18.2) |

65.2 (18.4) |

65.8 (18.8) |

66.5 (19.2) |

67.5 (19.7) |

69.2 (20.7) |

69.0 (20.6) |

69.0 (20.6) |

68.7 (20.4) |

67.6 (19.8) |

66.3 (19.1) |

67.0 (19.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 61.6 (16.4) |

59.9 (15.5) |

60.4 (15.8) |

61.8 (16.6) |

63.4 (17.4) |

65.3 (18.5) |

66.7 (19.3) |

67.0 (19.4) |

66.8 (19.3) |

66.5 (19.2) |

64.1 (17.8) |

62.7 (17.1) |

59.1 (15.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 59 (15) |

58 (14) |

56 (13) |

60 (16) |

60 (16) |

64 (18) |

65 (18) |

65 (18) |

64 (18) |

65 (18) |

62 (17) |

60 (16) |

56 (13) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.44 (62) |

1.19 (30) |

1.31 (33) |

0.90 (23) |

0.94 (24) |

0.67 (17) |

1.05 (27) |

0.76 (19) |

1.09 (28) |

1.58 (40) |

1.90 (48) |

2.00 (51) |

15.82 (402) |

History of Kahoʻolawe

Early Settlement

Around the year 1000, Polynesians settled on Kahoʻolawe. They set up small, temporary fishing villages along the coast. People also grew crops in some areas inland. Puʻu Moiwi, a leftover cinder cone, was home to the second-largest basalt quarry in Hawaiʻi. People mined this rock to make stone tools like koʻi (adzes).

Originally, Kahoʻolawe had dry forests and small streams. But as people cleared plants for firewood and agriculture, the land changed. It became an open savanna with grassland and scattered trees. Hawaiians built stone platforms for religious ceremonies. They also set up rocks as shrines for good fishing trips. They carved petroglyphs, or drawings, into flat rocks. These signs of earlier times can still be found on Kahoʻolawe. The island itself is seen as a kinolau, or body form, of the sea god Kanaloa.

We don't know exactly how many people lived on Kahoʻolawe. However, the lack of freshwater likely kept the population to only a few hundred. The largest settlement was Hakioawa, which faced Maui. Up to 120 people might have lived there at one time.

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1832 | 80 | — |

| 1836 | 80 | +0.0% |

| 1866 | 18 | −77.5% |

| 1910 | 2 | −88.9% |

| 1920 | 3 | +50.0% |

| 1930 | 2 | −33.3% |

| 1940 | 1 | −50.0% |

| 1950 | 0 | −100.0% |

| 1960 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1970 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1980 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1990 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2000 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2010 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2020 | 0 | 0.00% |

| U.S. Decennial Census; 1832, 1836, & 1866 Hawaiian Censuses Source: Manoa Library |

||

Times of Conflict

Fierce wars between powerful aliʻi (chiefs) damaged the land and caused the population to shrink. In the 18th century, during the War of Kamokuhi, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, the ruler of the Big Island of Hawaii, attacked Kahoʻolawe. He tried to take Maui from Kahekili II, the King of Maui, but he was not successful.

After European Contact

From 1778 to the early 1800s, sailors on passing ships said Kahoʻolawe was empty and dry. They reported it had no water or wood.

After missionaries arrived, King Kamehameha III of the Hawaiian Kingdom changed the death penalty to exile. Around 1830, Kahoʻolawe became a penal colony for men. Food and water were scarce, and some prisoners reportedly starved. Some even swam to Maui to find food. This law was ended in 1853.

A survey of Kahoʻolawe in 1857 found about 50 residents. About 5,000 acres (2,000 ha) were covered with shrubs. There was also a patch of sugarcane. Along the shore, tobacco, pineapple, gourds, pili grass, and scrub trees grew. Starting in 1858, the Hawaiian government leased Kahoʻolawe for ranching. Some ranches did better than others, but the lack of freshwater was always a problem. Over the next 80 years, the island's landscape changed a lot. Drought and uncontrolled overgrazing stripped away much of the plant life. Strong trade winds then blew away most of the rich topsoil, leaving behind hard, red dirt.

20th Century Changes

From 1910 to 1918, the Territory of Hawaii made Kahoʻolawe a forest reserve. They hoped to restore the island by planting new plants and removing livestock. This plan failed, and leases became available again. In 1918, a rancher named Angus MacPhee leased the island for 21 years. He planned to raise cattle there. By 1932, the ranch was doing fairly well. After heavy rains, native grasses and flowers would grow, but droughts always returned. In 1941, MacPhee rented part of the island to the U.S. Army. Later that year, due to ongoing drought, MacPhee took his cattle off the island.

Military Training Ground

On December 7, 1941, after the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Army declared martial law in Hawaii. They began using Kahoʻolawe to train American soldiers and Marines. These troops were heading west to fight in the Pacific War. Using Kahoʻolawe as a bombing range was seen as very important. The U.S. was fighting a new kind of war in the Pacific Islands. Success depended on accurate naval gunfire support to destroy enemy positions. This helped U.S. Marines and soldiers get ashore. Thousands of service members trained on Kahoʻolawe. They prepared for difficult battles on islands like the Gilbert and Marshall Islands and the Marianas.

Military training on Kahoʻolawe continued after World War II. During the Korean War, warplanes from aircraft carriers attacked enemy airfields and convoys. Fake airfields, military camps, and vehicles were built on Kahoʻolawe. Pilots trained at Barbers Point Naval Air Station on Oʻahu. They practiced finding and hitting these fake targets on Kahoʻolawe. Similar training happened during the Cold War and the Vietnam War. Fake aircraft, radar sites, and gun mounts were placed on the island for pilots and bombardiers to practice with.

In early 1965, the U.S. Navy conducted Operation Sailor Hat. This was to see how well ships could resist explosions. Three tests off Kahoʻolawe involved huge explosions. 500 tons of TNT were set off on the island near a target ship, the USS Atlanta (CL-104). The warship was damaged but did not sink. The blasts created a crater on the island called "Sailor Man's Cap." They might also have cracked the island's caprock, causing some groundwater to flow into the ocean.

Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) Movement

In 1976, a group called the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) filed a lawsuit. They wanted to stop the Navy from using Kahoʻolawe for bombing. They also wanted the Navy to follow new environmental laws and protect cultural sites. In 1977, a U.S. court allowed the Navy to continue using the island. However, the court told the Navy to study the environmental impact and list all historic sites.

The effort to get Kahoʻolawe back from the U.S. Navy grew from a new wave of awareness among Hawaiians. Charles Maxwell and other leaders planned to land on the island, which was still controlled by the Navy. The "first landing" began on Maui on January 5, 1976. Over 50 people from across Hawaii gathered to "invade" Kahoʻolawe on January 6, 1976. This date was chosen because it was close to the United States' 200th anniversary.

As the larger group headed to the island, military boats stopped them. But "The Kahoʻolawe Nine" kept going and successfully landed on the island. These brave people were Walter Ritte, Emmett Aluli, George Helm, Gail Kawaipuna Prejean, Stephen K. Morse, Kimo Aluli, Ellen Miles, Ian Lind, and Karla Villalba.

Sadly, the effort to retake Kahoʻolawe led to the loss of George Helm and Kimo Mitchell. They were trying to reach Kahoʻolawe with Billy Mitchell (no relation) when they faced bad weather. They could not reach the island and were never found, despite many rescue efforts. Walter Ritte became a leader in the Hawaiian community. He helped organize efforts for water rights, against land development, and to protect marine animals and ocean resources.

Kahoʻolawe Island Archeological District

|

Kahoʻolawe Island Archeological District

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| NRHP reference No. | 81000205 |

|---|---|

| Added to NRHP | March 18, 1981 |

On March 18, 1981, the entire island of Kahoʻolawe was added to the National Register of Historic Places. At that time, the Kahoʻolawe Archaeological District was found to have 544 recorded archaeological or historic sites. It also had over 2,000 individual features.

As part of efforts to save the soil, military personnel helped. They used explosives to break up the hard ground so that young trees could be planted. Used car tires were brought to Kahoʻolawe and placed in deep gullies. This helped slow down the red soil washing away from the bare uplands to the shores. Bombs and scrap metal were picked up by hand and taken by trucks to a collection site. Kahoʻolawe is also on the Hawaiʻi Register of Historic Places.

End of Live-Fire Training

In 1990, President George H. W. Bush ordered an end to live-fire training on the island. The U.S. Department of Defense then created a commission. This group was to suggest how Kahoʻolawe should be given from the U.S. government to the state of Hawaii.

Transfer and Cleanup Efforts

In 1993, Senator Daniel Inouye of Hawaii helped pass a law. This law directed the U.S. government to give Kahoʻolawe and its surrounding waters to the state of Hawaii. The law also aimed to clear or remove unexploded ordnance (UXO). UXO are bombs or shells that did not explode. The goal was also to restore the island's environment. This would allow the island to be used safely for cultural, historical, archaeological, and educational purposes.

In response, the Hawaii Legislature created the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission. This commission manages the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve. As the law required, the Navy officially transferred the island to Hawaii on May 9, 1994.

The U.S. Navy kept control of access to the island until the cleanup was done. This was set for November 11, 2003, at the latest. The state agreed to make a plan for Kahoʻolawe's use. The Navy agreed to create a cleanup plan based on this use plan. They would carry out the cleanup if Congress provided the money.

In July 1997, the Navy hired a company to clear unexploded ordnance. They started work in November 1998. From 1998 to 2003, the U.S. Navy carried out a large cleanup. They removed unexploded ordnance and other dangers from Kahoʻolawe. However, they could not remove all hazardous materials. Some danger still remains. The Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission has a plan to manage this risk for people using the reserve. They also have a safety program and work with stewardship groups.

Wildfire on Kahoʻolawe

In 2020, a wildfire burned over 30% of the island. Firefighters stopped trying to put out the fire on the first day. This was due to worries about unexploded ordnance on the island.

Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve

In 1993, the Hawaiian State Legislature created the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve. This reserve includes the entire island and its ocean waters for two miles (three km) around the shore. By state law, Kahoʻolawe and its waters can only be used for:

- Native Hawaiian cultural, spiritual, and traditional purposes

- Fishing

- Environmental restoration

- Historic preservation

- Education

All commercial uses are not allowed.

The legislature also created the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission. This commission manages the reserve. The island is held in trust for a future Native Hawaiian self-governing group. Restoring Kahoʻolawe will require a plan to control erosion, bring back plants, refill the water table, and slowly replace foreign plants with native ones. Plans will include building dams in gullies and reducing rainwater runoff. In some areas, non-native plants will be used temporarily to hold the soil. Then, permanent native species will be planted.

Plants used for bringing back vegetation include:

- ʻaʻaliʻi (Dodonaea viscosa)

- ʻāheahea (Chenopodium oahuense)

- kuluʻī (Nototrichium sandwicense)

- Achyranthes splendens

- ʻūlei (Osteomeles anthyllidifolia)

- kāmanomano (Cenchrus agrimonioides var. agrimonioides)

- koaiʻa (Acacia koaia)

- alaheʻe (Psydrax odorata)

In July 2015, a plan was suggested to restore Hawaiian bird life and native ecosystems on Kahoʻolawe. This plan was a partnership between KIRC and other groups. The plan aims to restore Kahoʻolawe Island by removing feral cats, rats, and mice. The document looks at the biological, cultural, financial, and legal parts of getting rid of these animals.

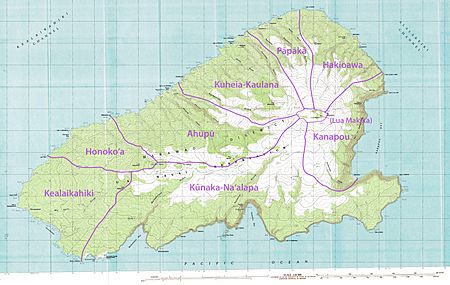

Traditional Land Divisions

Traditionally, Kahoʻolawe was an ahupuaʻa of Honuaʻula. This was one of the twelve moku (districts) of Maui. Kahoʻolawe was then divided into twelve smaller ʻili (land sections), which were later combined into eight. The eight ʻili are listed below, starting from the northeast and going counterclockwise:

|

The borders of most of these ʻili meet at the edge of the Lua Makika crater. However, the crater area itself is not part of any ʻili. Other sources say the island was divided into 16 ahupuaʻa. These belonged to three larger moku: Kona, Ko’olau, and Molokini.

See also

In Spanish: Kahoolawe para niños

In Spanish: Kahoolawe para niños

- ʻAlalakeiki Channel

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Hawaii - Kahoʻolawe

- Vieques, Puerto Rico - a smaller island that was also used for US Navy bombings and had protests against them.

- Desert island

- List of islands

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |