History of Spain (1808–1874) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Spain

España

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1813–1873 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Motto: Plus Ultra

("Further Beyond") |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Anthem: Marcha Real

("Royal March") (1813–1822; 1823–1873) Himno de Riego ("Anthem of Riego") (1822–1823) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

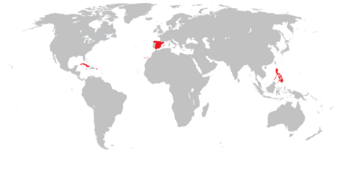

The Kingdom of Spain after the loss of its American territories.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Madrid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Catholicism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Spanish, Spaniard | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Cortes Generales | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congress of Deputies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 July 1813 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1822 territorial division of Spain

|

1822 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1833 territorial division of Spain

|

1833 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1873 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | ES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 19th century was a very difficult time for Spain. The country faced many challenges and changes. From 1808 to 1814, Napoleon's army occupied Spain. This led to a destructive war for freedom.

After the war, Spain struggled between new liberal ideas and the old system of absolute rule by kings. King Ferdinand VII often changed his mind about the country's laws. This caused a lot of political unrest.

Spain also lost most of its colonies in the Americas during this century. Only Cuba and Puerto Rico remained. The country also saw civil wars, known as the Carlist Wars. These wars were fought between government forces and those who wanted to keep the old ways.

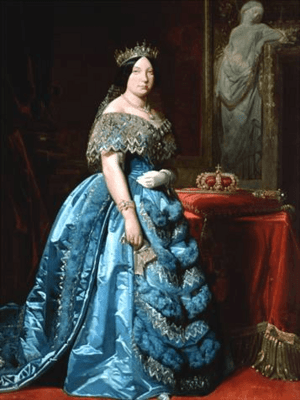

Many people were unhappy with Queen Isabella II's government. This led to military takeovers and attempts to overthrow the government. In 1868, a revolution removed Isabella from power. This led to a new constitution and a brief period with a new king, Amadeo of Savoy. After he left, Spain became the First Spanish Republic. However, this republic also ended with a military takeover. The old royal family, the Bourbons, returned to power in 1874.

Contents

- Changes in Power: Kings and Napoleon (1808)

- Fighting for Freedom: Napoleon's Invasion (1808–1814)

- Spain's First National Assembly (1810–1814)

- King Ferdinand VII Returns (1814–1820)

- The Three Liberal Years (1820–1823)

- The "Ominous Decade" (1823–1833)

- Spanish American Independence (1810–1833)

- The Carlist War and Regents (1833–1843)

- Moderate Rule (1843–1849)

- Rule by Military Leaders (1849–1856)

- The End of the Old Order (1856–1868)

- Democratic Period (1868–1874)

- Economic and Social Changes

- See also

Changes in Power: Kings and Napoleon (1808)

The reign of King Charles IV was not very strong. His wife, Maria Luisa, and his minister, Manuel de Godoy, made most of the decisions. Many people criticized Godoy. Charles's son, Ferdinand, gained support against his father.

A crowd supporting Ferdinand attacked Godoy and arrested him. Under pressure, Charles IV gave up his throne to his son, Ferdinand VII. Meanwhile, Napoleon had already sent troops into Spain. Napoleon called Ferdinand to meet him in France. Ferdinand went, thinking Napoleon would confirm him as king.

But Napoleon also called Charles IV. Napoleon then made Ferdinand give the throne back to his father. Charles IV, not wanting his son to be his heir, then gave the throne to Napoleon himself. Napoleon then made his older brother, Joseph Bonaparte, the new king of Spain.

A group of Spanish leaders approved the Bayonne Constitution. This was Spain's first constitution. It was important because it suggested that people from different regions of Spain and its colonies should have a say in government.

Fighting for Freedom: Napoleon's Invasion (1808–1814)

Some Spaniards supported Napoleon's takeover. However, many cities and regions in Spain resisted. They formed local governments called juntas to rule in the name of the old king, Ferdinand VII. Spanish colonies in America also formed juntas. They did not see Joseph I as a rightful king.

Bloody battles took place in Spain and Portugal during the Peninsular War. Much of the fighting involved guerrilla tactics, where small groups used surprise attacks.

Spain's First National Assembly (1810–1814)

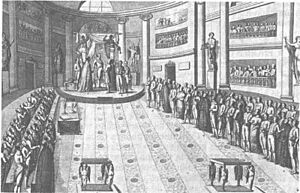

The Cortes of Cádiz was Spain's first national assembly. It claimed power over all of Spain and its empire. This was a big step, as it meant the end of the old kingdoms. It also recognized the colonies as part of the Spanish nation. The first meeting was on September 24, 1810.

French forces took control of southern Spain in 1809. The Central Junta, which was the main Spanish government, moved to Cádiz. The French tried to capture Cádiz for over two years, but they failed. The Central Junta then created a five-person Regency. This Regency called for the meeting of the Cortes of Cádiz.

The delegates were supposed to represent all provinces and colonies. However, elections could not be held in many areas. So, the Regency appointed temporary representatives. The Cortes declared that it represented the Spanish nation. This included Spain and the Americas.

The Cortes opened its session in September 1810. It had 97 deputies. Almost half of them were residents of Cádiz who served as stand-ins.

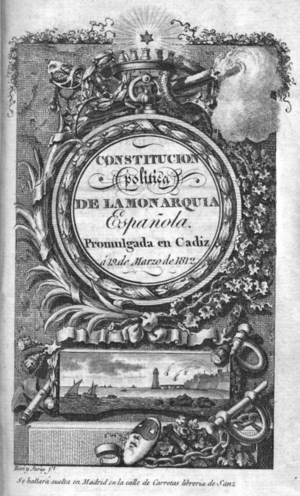

The Spanish Constitution of 1812 was created on March 19, 1812. It ended the Inquisition and absolute monarchy. It also introduced important ideas like voting rights for all men, national power, a king who followed a constitution, and freedom of the press. It also supported land reform and free markets.

King Ferdinand VII Returns (1814–1820)

On March 24, 1814, King Ferdinand VII returned to Spain. He immediately got rid of the 1812 Constitution. He had already agreed with the church and nobles to bring back the old system. Many liberals felt betrayed by the king they had supported.

The local juntas that had fought against Joseph I also lost faith in Ferdinand. Even the army, which had liberal ideas, was unhappy. At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, other European powers supported Spain's old absolute monarchy.

Meanwhile, the Spanish Empire in the Americas had largely supported Ferdinand VII against Napoleon's brother. However, they did not want absolute rule. They wanted to govern themselves. The juntas in the Americas did not accept either the French or Spanish governments.

The Three Liberal Years (1820–1823)

A group of liberal army officers rebelled in Cádiz. They were supposed to go to the Americas. Led by Rafael del Riego, they demanded that the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812 be brought back. Other army groups across Spain supported them.

King Ferdinand agreed to their demands and swore to uphold the constitution. A liberal government was appointed. However, the king was not happy with the new system.

For three years, Spain had liberal rule. The government tried to reorganize Spain into 52 provinces. This aimed to reduce the power of regions like Aragon, Navarre, and Catalonia. These regions, along with the king, disliked the liberal government.

The liberal government also clashed with the Roman Catholic Church. It tried to industrialize, which upset old trade groups. The Spanish Inquisition was ended again. This led to accusations that the liberals were too French-like. Some radical liberals even tried to get rid of the monarchy entirely in 1821. This showed how fragile the liberal government was.

In 1823, a more radical liberal government was elected. This made Spain even more unstable. The army, which had brought the liberals to power, started to lose faith. The economy was not improving. In 1823, a rebellion in Madrid had to be stopped. The Jesuits, who had been allowed back by Ferdinand, were banned again. King Ferdinand lived under house arrest during this time.

Other European powers were worried about Spain's liberal government. In 1822, the Congress of Verona allowed France to intervene. Louis XVIII of France, a very conservative king, was happy to end Spain's liberal experiment. A large French army, called the "100,000 Sons of Saint Louis", crossed the Pyrenees in April 1823. The Spanish army, divided by internal problems, offered little resistance. The French took Madrid and put Ferdinand back as an absolute monarch.

The "Ominous Decade" (1823–1833)

After becoming an absolute ruler again, King Ferdinand VII tried to bring back old conservative values. The Jesuit Order and the Spanish Inquisition were restored. Some power was given back to the provinces of Aragon, Navarre, and Catalonia.

Ferdinand did not want to accept the loss of the American colonies. However, the United Kingdom and the United States supported the new Latin American republics. They made it clear they would oppose any attempt to reconquer them. This led to the Monroe Doctrine. Ferdinand realized that keeping peace at home was more important than fighting for the empire abroad. Spain and its American colonies would now go their separate ways.

Ferdinand VII offered a general pardon to those involved in the 1820 coup. However, Rafael del Riego, who started the coup, was executed. He became a hero for the liberal cause. His anthem, El Himno de Riego, would be used by the Second Spanish Republic much later.

The rest of Ferdinand's rule focused on bringing stability to Spain. He also worked to fix the country's finances, which were ruined by the Napoleonic Wars. The end of the wars in the Americas helped the government's money situation. By the end of Ferdinand VII's reign, Spain's economy was getting better. A revolt in Catalonia was put down in 1827. Overall, this period was mostly peaceful.

Ferdinand's main concern after 1823 was who would rule after him. He had two daughters from his four marriages. However, the law from Philip V of Spain said women could not inherit the throne. By this law, his brother, Carlos, would be the next king.

Carlos was a very conservative person. He wanted to bring back traditional values and get rid of any constitutional ideas. He also wanted a very close relationship with the Roman Catholic Church. Ferdinand VII, though not a liberal, was worried about Carlos's extreme views.

In 1830, Ferdinand VII, advised by his wife Maria Christina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, issued a new law. This Pragmatic Sanction allowed women to become queen. This meant his infant daughter, Isabella, would be the next ruler, not his brother Carlos. Carlos disagreed with this law. He left Spain for Portugal.

Ferdinand VII died in 1833 at age 49. His daughter Isabella became queen, as the new law allowed. His wife, Maria Christina, became regent because Isabella was only three years old. Carlos claimed he was the rightful heir. This led to many years of civil war and unrest.

Spanish American Independence (1810–1833)

As early as 1810, cities like Caracas and Buenos Aires in the Americas declared independence from Napoleon's government in Spain. They sent ambassadors to the United Kingdom. Britain's alliance with Spain also shifted trade from Spain to Britain for many Latin American colonies.

When King Ferdinand VII returned to power, he got rid of the 1812 Constitution. Spanish liberals were against this. The new American states were careful not to lose their independence. Local leaders, merchants, and nationalists joined forces against Spain in the New World.

Ferdinand wanted to reconquer the colonies. However, the British government opposed this, as it would hurt their new trade interests. Many in Spain, especially liberal military officers, also opposed reconquest. They saw the empire as old-fashioned and sympathized with the liberal revolutions in the Americas.

Spanish forces arrived in the American colonies in 1814. They were briefly successful in regaining control. Simón Bolívar, a revolutionary leader, was forced into exile. But in 1816, Bolívar returned to South America. He defeated Spanish forces at the Battle of Boyacá in 1819, ending Spanish rule in Colombia. Venezuela was freed in 1821. Argentina declared independence in 1816. Chile was lost to Spain in 1814 but permanently freed in 1817 by an army led by José de San Martín.

Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, and Central America were still under Spanish control in 1820. King Ferdinand VII wanted to retake the lost parts of the empire. A large expedition was prepared in Cádiz. However, this army would cause political problems in Spain itself.

José de San Martín entered Peru in 1820. In 1821, the people of Lima invited him to their city. The Spanish viceroy fled. It was not until Simón Bolívar and Antonio José de Sucre arrived in 1823 that the Spanish forces were defeated. This happened at the battles of Junin and Ayacucho. The entire Spanish army in Peru was captured. The Battle of Ayacucho marked the end of the Spanish Empire on the American mainland.

Mexico had revolted in 1811 under Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. But resistance was mostly small guerrilla groups. In 1821, Mexico, led by Agustin de Iturbide and Vincente Guerrero, proposed the Plan de Iguala. This plan called for an independent Mexican monarchy. The liberal government in Spain showed less interest in military reconquest. However, it rejected Mexico's independence. Spain finally gave up all plans of military reconquest after King Ferdinand VII died in 1833.

The Carlist War and Regents (1833–1843)

After Ferdinand VII died, his wife Maria Cristina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies became regent for their young daughter, Isabella. She formed an alliance with liberals against the conservatives. These conservatives supported Ferdinand's brother, Infante Carlos.

Carlos supported the old regional privileges called fueros. He received strong support from the Basque country, Aragon, and Catalonia. At first, the Carlists faced many defeats. But Carlos appointed Tomás de Zumalacárregui, a veteran of the Peninsular War, as his commander. Zumalacárregui quickly turned the tide. By 1835, the Carlists controlled much of northern Spain.

The government was in a desperate situation. Rumors of a liberal coup against Maria Cristina spread in Madrid. France and Britain supported Maria Cristina's side. Carlos joined his troops on the battlefield. He ordered Zumalacárregui to take a port, but the general was wounded and died. Some suspected Carlos had him killed.

After failing to take Madrid and losing their popular general, the Carlist armies weakened. Isabella's forces, led by General Baldomero Espartero, gained strength. In 1836, Espartero won a key victory. Maria Cristina was forced to accept a new constitution in 1837. This constitution increased the power of the Spanish parliament, the cortes. It also made the state responsible for the church and led to the disbandment of some religious orders. The Jesuits were expelled again in 1835.

Spain's government was deep in debt because of the Carlist war. In 1836, the government president, Juan Álvarez Mendizábal, proposed selling church property. This process was called desamortización. Many liberals saw this as fair, as they believed the clergy had sided with the Carlists. Mendizábal also noted that the church owned vast amounts of unused land. The Mendizábal government also passed a law guaranteeing freedom of the press.

Espartero's forces pushed the Carlists back north. Espartero convinced the Queen-Regent to compromise with the regions on their autonomy. The Convention of Vergara in 1839 protected the regional privileges and recognized the Carlists' defeat. Don Carlos went into exile again.

After the Carlist threat ended, Maria Cristina tried to undo the 1837 Constitution. This angered the liberals. She then tried to weaken the power of local governments in 1840. This led to her downfall. She was forced to name General Baldomero Espartero, the hero of the Carlist War, as president of the government. Maria Cristina resigned as regent after Espartero tried to make reforms.

In May 1841, the cortes named Baldomero Espartero as regent. Espartero was a great commander but not good at politics. His rule was very strict. He clashed with the government over the choice of the young queen's tutor. Maria Cristina, from Paris, criticized his decisions.

In September 1841, some generals tried to overthrow Espartero. He crushed the rebellion harshly, making him unpopular. The cortes chose an old rival as chief minister. Another uprising in Barcelona in 1842, against his free trade policies, led him to bombard the city. This weakened his power. In 1843, generals Ramón Narváez and Francisco Serrano overthrew Espartero. He then fled to England.

Moderate Rule (1843–1849)

The cortes, tired of constant revolutions, decided not to name another regent. Instead, they declared that 13-year-old Isabella II was old enough to rule. Isabella was influenced by many different groups. This made it hard for her to make decisions and angered those who wanted progress.

Salustiano Olózaga became the first president of the Council of Ministers after Espartero's fall. However, he quickly lost support. He was accused of forcing the queen to sign an order. Olózaga had to resign after only fifteen days. He was replaced by Luis González Bravo, a moderate. This began a decade of "moderate" rule. Luis González Bravo was Isabella's first stable president. However, Isabella's reign was often unstable due to various opposition parties.

Luis González Bravo dissolved the cortes and ruled by royal order. He declared Spain to be in a state of emergency. He also removed some institutions set up by the liberals, like elected city councils. To prevent another Carlist uprising, he created the Guardia Civil. This force combined police and military roles to keep order.

A new constitution was written by the moderates in 1845. It was supported by the new government led by General Ramón María Narváez. Narváez's government made reforms to stabilize the country. The cortes wanted to centralize the government. A law in 1845 reduced local power, giving more control to Madrid. This contributed to a revolt in 1847 and a return of Carlism in the provinces. A law in 1846 limited voting rights to only the wealthy.

Narváez stopped the sale of church lands. This made things difficult, as the sales had helped Spain's finances. The Carlist War and previous governments had left Spain's money in a terrible state. Narváez put Alejandro Mon in charge of finances. Mon successfully reformed the tax system. With better finances, the government could rebuild the military. In the 1850s and 1860s, Spain made improvements in infrastructure and had successful campaigns in Africa.

Isabella was convinced to marry her cousin, Francis, Duke of Cádiz. Her younger sister was married to the French king's son. This "Affair of the Spanish Marriages" almost caused a war between Britain and France. The affair also made the queen unpopular in Spain.

In 1846, a major rebellion broke out in northern Catalonia, called the Second Carlist War. Rebels fought against government forces. The rebellion grew, and by 1848, Carlos supported it. He named Ramón Cabrera as commander. A force of 10,000 men was raised. Narváez was again named President of the Council of Ministers. The biggest battle was inconclusive. Cabrera was wounded, and the rebellion ended by May 1849.

Rule by Military Leaders (1849–1856)

Ramón Narváez was followed by Juan Bravo Murillo. Murillo was a practical politician. He tried to advance Spanish industry and trade. He surrounded himself with experts who worked to improve Spain's economy. He also started building a railway network in Spain.

Murillo signed an agreement with the Vatican about religion in Spain. It confirmed that Roman Catholicism was the state religion. It also said that the state would regulate the church's role in education. The state also stopped the sale of church lands.

Murillo tried to reduce the power of the cortes and allow the executive to make laws by decree. However, the cortes convinced the queen to fire him.

The next presidents of the Council of Ministers ruled briefly. The army often interfered in government affairs. In July 1854, a major rebellion broke out. This rebellion brought together many groups unhappy with the government. The Crimean War had caused grain prices to rise and led to a famine. Riots broke out in cities. Liberals, angry at the "moderate" dictatorship and corruption, joined the revolution.

General Leopoldo O'Donnell led the revolution. After a battle, he issued the Manifesto of Manzanares. This manifesto supported Spain's former liberal leader, Baldomero Espartero. The "moderate" government collapsed, and Espartero returned to politics.

Espartero became President of the Council of Ministers. He tried to rebuild the liberal government. He worked on a new constitution to replace the "moderate" constitution of 1845. However, the cortes resisted. Espartero's coalition included both liberals and moderates, who disagreed on the new constitution. Espartero's constitution included freedom of religion, freedom of the press, and more voting rights.

Espartero also supported selling communal lands. This was opposed by the moderates, the queen, and General O'Donnell. Espartero's alliance with O'Donnell broke down. The queen named Leopoldo O'Donnell as president. O'Donnell also struggled to work with the government. He tried to combine Espartero's constitution with the 1845 document. This led to O'Donnell's removal. The "Constitution of 1855" was never fully put into place.

The End of the Old Order (1856–1868)

Ramón María Narváez, a symbol of conservative rule, returned to power in 1856. Isabella II now favored the "moderates." Espartero, frustrated, retired from politics. Narváez's new government undid Espartero's reforms. The 1845 Constitution was fully restored.

Isabella grew tired of this constant back-and-forth. She replaced Narváez with Francisco Armero Peñaranda. However, Peñaranda found it hard to pass conservative laws. The "moderate" party was divided. Isabella then replaced Peñaranda with Francisco Javier Istúriz. Istúriz lacked support from conservatives. Isabella then gave O'Donnell's "Unión Liberal" another chance in 1858.

This government was the longest-lasting under Isabella. It lasted almost five years until 1863. O'Donnell tried to create a stable government by combining moderate and liberal ideas. His government successfully brought stability at home. They also projected power abroad. Spain supported French expeditions in Cochinchina (Vietnam) and Mexico. They also had a successful campaign in Morocco. O'Donnell personally led the army in Morocco and was named Duque de Tetuán. A new agreement with the Vatican in 1859 allowed for more sales of church property.

The coalition broke apart in 1863 over the issue of selling church property. The "moderates" attacked O'Donnell for being too liberal. His government collapsed in February 1863.

The "moderates" immediately tried to undo O'Donnell's laws. But Spain's economy worsened. Isabella turned to Ramón Narváez again in 1864 to control the situation. This angered the liberals. General Juan Prim launched a major uprising against the government. O'Donnell brutally crushed it. The queen again fired O'Donnell and replaced him with Narváez.

By this time, Narváez and many in the cortes doubted the queen's ability to rule. A Republican party had been growing stronger since 1854. This party sometimes worked with the "Unión Liberal" in the cortes.

Democratic Period (1868–1874)

The Glorious Revolution

A rebellion in 1866 led by Juan Prim showed that there was serious unrest in Spain. Liberals and republicans living in exile made agreements in 1866 and 1867. These agreements planned a major uprising. This time, the goal was not just to change the government leader. It was to overthrow Queen Isabella herself. Many saw her as the cause of Spain's problems.

Isabella's constant changes between liberal and conservative policies had angered many groups by 1868. Leopoldo O'Donnell's death in 1867 caused his "Unión Liberal" party to fall apart. Many of its supporters joined the movement to remove Isabella.

The revolution began in September 1868. Naval forces under Admiral Juan Bautista Topete rebelled in Cádiz. Generals Juan Prim and Francisco Serrano spoke out against the government. Much of the army joined the revolutionary generals. The queen's loyal generals were defeated at the Battle of Alcolea. Isabella then fled to France and lived in Paris until her death in 1904.

Provisional Government

The revolutionaries had overthrown the government, but they lacked a clear plan for what came next. The group of liberals, moderates, and republicans now had to find a new government. Control passed to Francisco Serrano. The cortes at first rejected the idea of a republic. Serrano was named regent while they searched for a suitable king. A truly liberal constitution was written and passed by the cortes in 1869. This was the first such constitution since 1812.

Finding a suitable king was very difficult. Juan Prim, the government chief, said it was "as hard as to find an atheist in Heaven!" The old Espartero was considered, but he refused. Many suggested Isabella's young son, Alfonso. But people worried he would be controlled by his mother. A proposal to Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen even led to the Franco-Prussian War.

In August 1870, an Italian prince, Amadeo of the House of Savoy, was chosen. He was the younger son of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy. Amadeo had fewer political problems than a German or French candidate. He also had strong liberal beliefs.

King Amadeo's Reign

Amadeo was officially elected King Amadeo I of Spain on November 3, 1870. He arrived in Cartagena on November 27. On the same day, Juan Prim, his main supporter, was assassinated. Amadeo swore to uphold Spain's constitution.

However, Amadeo had no experience as a king. Spain's politics were very unstable. Amadeo faced a cortes that saw him as an outsider. Politicians worked both with and against him. A Third Carlist War broke out in 1872. In February 1873, Amadeo declared that the people of Spain were "ungovernable" and gave up his throne.

First Spanish Republic (1873–1874)

After Amadeo left, the cortes declared the First Spanish Republic.

Economic and Social Changes

The Napoleonic Wars severely harmed Spain's economy. The Peninsular War destroyed towns and farmlands. The population declined sharply due to deaths, people moving away, and disrupted family life. Farmers lost crops and livestock. Widespread poverty reduced demand for goods.

Trade was disrupted, hurting industries and services. The loss of the vast colonial empire reduced Spain's wealth. By 1820, Spain was one of Europe's poorest and least developed countries. Three-fourths of the people could not read or write. Spain had natural resources like coal and iron. But its transportation system was very basic, with few canals or navigable rivers. Road travel was slow and costly. British railway builders did not invest, as they saw little potential. Eventually, a small railway system was built around Madrid.

The government used high tariffs, especially on grain. This further slowed economic development. For example, eastern Spain could not import cheap Italian wheat. It had to rely on expensive local products transported over poor roads. The export market collapsed, except for some farm products.

See also

- History of Spain (1700-1808)

- Spanish confiscation

- Mexican War of Independence

- Spanish American wars of independence

- Contemporary history of Spain

- Restoration (Spain)

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |