Paleontology in Pennsylvania facts for kids

Paleontology in Pennsylvania is all about studying ancient life in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. This includes fossils found there and research done by people from Pennsylvania. The state's rocks tell a story stretching from the very old Precambrian time to the recent Quaternary period.

Millions of years ago, during the early Paleozoic Era, Pennsylvania was covered by a warm, shallow sea. Many creatures lived in this sea. These included brachiopods (shellfish), bryozoans (tiny colonial animals), crinoids (sea lilies), graptolites (small colonial animals), and trilobites (ancient arthropods). An armored fish called Palaeaspis appeared during the Silurian Period. By the Devonian Period, other types of fish swam in the waters. On land, some of the world's oldest tetrapods (four-legged animals) left their footprints. These later turned into fossils. Some of Pennsylvania's most important fossil discoveries come from its Devonian rocks.

During the Carboniferous Period, Pennsylvania was a huge swamp. It was filled with many different kinds of plants. The second half of this period is even named the Pennsylvanian Period. This name honors Pennsylvania's rich fossil record from that time. By the end of the Paleozoic Era, the state was no longer swampy.

In the Mesozoic Era, Pennsylvania was home to dinosaurs and other reptiles. They left behind many fossil footprints. We don't know much about the early to middle Cenozoic Era in Pennsylvania. But during the Ice Age, the state looked like a cold, treeless tundra.

Long ago, local Delaware people used to smoke mixtures of fossil bones and tobacco. They believed this would bring them good luck and help their wishes come true. By the late 1800s, scientists began formally studying fossils in Pennsylvania. Around this time, a dinosaur skeleton from nearby New Jersey, Hadrosaurus foulkii, became the first dinosaur skeleton ever put on display. It was shown at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Today, the Devonian trilobite Phacops rana is Pennsylvania's official state fossil.

Contents

Ancient Life in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania has no known fossils from the very early Precambrian time. So, the state's fossil story begins in the Paleozoic Era. During the early Paleozoic, Pennsylvania was near the eastern coast of a large continent called Laurentia. Much of the state was covered by a nearby sea.

Life in Ancient Seas

During the Late Ordovician Period, Pennsylvania's seas were home to many creatures. These included brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, graptolites, mollusks, pelecypods (clams), starfish, and trilobites. In the next period, the Silurian, an ancient fish called Palaeapsis bitruncata left its remains in Perry County.

First Animals on Land

During the Devonian Period, early tetrapods (four-legged animals) left footprints near Warren. These were once thought to be the oldest evidence of land vertebrates. But even older footprints have since been found in Poland. Later Devonian rocks show primitive fish and more signs of early tetrapods.

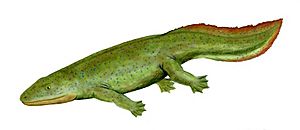

One important fossil site is called Red Hill. It is found along a road in Clinton County. This site shows what a floodplain environment was like. It was mostly covered by the plant Archaeopteris. An important early tetrapod, Hynerpeton, was found at Red Hill. This animal is a key transitional fossil, showing how life moved from water to land.

Swamps and Coal Forests

The next period, the Carboniferous, means "coal-bearing." This time is also called the "age of amphibians" or the "age of coal swamps." During the Carboniferous, Laurentia joined with another continent called Gondwana. Together, they formed the supercontinent Pangaea. At this time, the sea pulled back from Pennsylvania.

During the Mississippian Period, an early tetrapod left tracks in the Pottsville area. A series of swamps formed where the sea used to be. The plants of the late Carboniferous Pennsylvanian Period in Pennsylvania included many types of ferns and tree-like plants. Some examples are Annularia, Cordaites, Mariopteris, and Neuropteris. However, these swamps dried up before the end of the Paleozoic Era. There's a gap in the rock record after the Carboniferous. This is because old sediments were being worn away faster than new ones were laid down.

Dinosaurs and Ancient Reptiles

During the Mesozoic Era, Pangaea began to break apart. This breaking apart created large rift valleys in eastern Pennsylvania. These areas were covered by huge lakes during the Late Triassic Period.

Many dinosaur tracks have been found in Pennsylvania. Atreipus tracks are known from the Late Triassic Lockatong Formation in places like Arcola and Gwynned. Grallator tracks have been found in the Late Triassic Passaic Formation in Schwenksville. Ancient crocodile-like reptiles also left fossils. A type of reptile called Galtonia gibbidens left teeth in the Emigsville area. Rutiodon fossils were found in York County along the Little Conewago Creek. Also near Emigsville, two metoposaurs (ancient amphibians) were found in what is now a copper mine.

Ice Age Animals

There are very few rocks from the Tertiary Period of the Cenozoic Era in Pennsylvania. However, during the Pleistocene Ice Age, glaciers covered much of the state. Areas not covered by ice became a tundra, with sedges and willows. A nearly complete mastodon skeleton was found in Marshalls Creek. You can see it on display at the state museum.

Studying Pennsylvania's Fossils

Early Discoveries and Research

One of the first important events in Pennsylvania paleontology happened on October 5, 1787. Caspar Wistar and Timothy Matlack showed a possible dinosaur bone to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. This bone was found in New Jersey.

During the industrial revolution, coal mines in Pennsylvania led to accidental discoveries of early fossil footprints from tetrapods. These tracks often appeared on the ceilings of mine tunnels. Later, in the 1840s, Charles Lyell looked at some local tracks. People thought they were from ancient birds or mammals. But Lyell found they were actually petroglyphs (rock carvings) made by local Native American people.

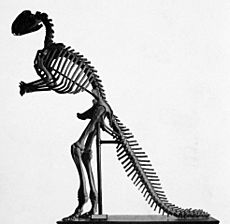

In 1868, Joseph Leidy worked with artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. They put together the skeleton of Hadrosaurus foulkii for the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. This was the first dinosaur skeleton ever put on public display anywhere in the world! It became one of the most popular exhibits at the academy. It even increased visitors by up to 50%.

In 1878, Edward Drinker Cope described two dinosaur teeth. He said they belonged to Thecodontosaurus gibbidens. These are the only known dinosaur skeletal remains from Pennsylvania. In 1889, dinosaur tracks were found at a small quarry near Goldsboro in York County. These prints were from the type of track called Atreipus. They were preserved in Late Triassic rocks. Near the end of the 19th century, in 1895, Andrew Carnegie gave money to create Pittsburgh's Carnegie Museum.

20th Century Discoveries

One of the first big fossil finds in the 20th century was in 1902. Dinosaur tracks were found at a quarry near Graterford in Montgomery County. Another important discovery in the early 1900s was a lower jaw from an amphibian called Calamops. It was found in Late Triassic rocks at Holicong. This is the oldest vertebrate fossil from the Hartford or Newark Basins.

In 1923, the Reading Railroad tunnel at Gwynned was opened up. This revealed many Late Triassic fossils. Later, in 1933, two Anchisauripus tracks were found near Yocumtown in York County. Dinosaur tracks from the Late Triassic were also found near the Gettysburg battle sites in 1933.

Bradford Willard of the Pennsylvania Topographic and Geologic Survey found a dinosaur footprint in 1934. This was near New Cumberland while a road was being made wider. The track was found with fern prints, mud cracks, and even raindrop marks. More Late Triassic dinosaur tracks were found near the Gettysburg battle sites in 1937. News reports from that time said the tracks were about six inches long. They were left by animals with a thirty-inch stride. Some tracks were from chicken-sized animals.

That same year, Elmer R. Haile Jr. collected Late Triassic fossil footprints from the Trostle Quarry near York Springs in Adams County. These included the dinosaur track type Atreipus and other reptile tracks like Brachychirotherium. Another big discovery in 1937 was more Atreipus prints found in Late Triassic rocks at York Springs.

One of the last major finds of the 1930s was in 1939. Earl L. Poole found many Late Triassic fossil reptile footprints near Perkiomen Creek. This was at a quarry where rock was being dug up for highway material. This site is now called the Squirrel Hill Quarry. A newspaper article from that time said the find included dozens of tracks from chicken-sized animals. There were also about six tracks from turkey-sized ones, and one single track from an animal as heavy as a horse.

In 1952, Whilhelm Bock said some of the Squirrel Hill footprints were from the dinosaur track type Grallator. He thought other reptile tracks were not from dinosaurs. That same year, Bock described a new track type called Anchisauripus gwynnedensis. These were found in Late Triassic rocks at the Reading Railroad in Gwynned.

In 1988, the Devonian trilobite Phacops rana was chosen as Pennsylvania's official state fossil. In 1994, the dinosaur teeth that Cope had called Thecodontosaurus gibbidens were renamed Galtonia gibbidens.

People Who Studied Fossils

Born in Pennsylvania

- Edward Drinker Cope was born in Philadelphia on July 28, 1840.

- Childs Frick was born in Pittsburgh in 1883.

- William More Gabb was born in Philadelphia on January 16, 1839.

- Joseph Leidy was born in Philadelphia on September 9, 1823.

- Paul S. Martin was born in Allentown in 1928.

Died in Pennsylvania

- Edward Drinker Cope died in Philadelphia on April 12, 1897.

- William More Gabb died in Philadelphia on May 30, 1878.

- Joseph Leidy died in Philadelphia on April 30, 1891.

- Charles M. Wheatley died in Phoenixville on May 6, 1882.

Museums with Fossils

- Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia

- Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh

- Delaware County Institute of Science, Media

- Earth & Mineral Sciences Museum and Art Gallery, University Park, State College

- Everhart Museum, Scranton

- North Museum of Natural History and Science, Lancaster

- State Museum of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg

- Reading Public Museum, West Reading

- Wagner Free Institute of Science, Philadelphia

Fossil Clubs and Groups

- Delaware Valley Paleontological Society