Reign of Alfonso XIII of Spain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Reign of Alfonso XIII of Spain

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1885–1931 | |||||||

|

Anthem: Marcha Real

|

|||||||

| Capital | Madrid | ||||||

| Recognised national languages | Spanish | ||||||

| Religion | Catholic church | ||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy (1885-1923) Dictatorship (1923-1931) |

||||||

| Alfonso XIII | |||||||

| President of the Spanish Council of Ministers | |||||||

|

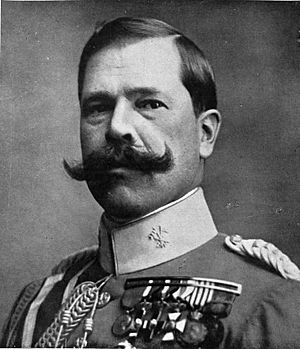

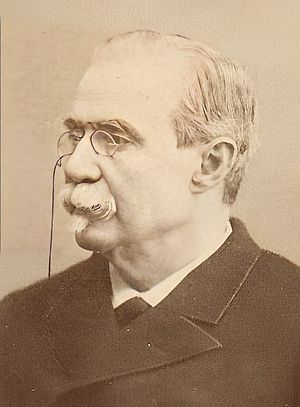

• 1885-1890

|

Práxedes Mateo Sagasta | ||||||

|

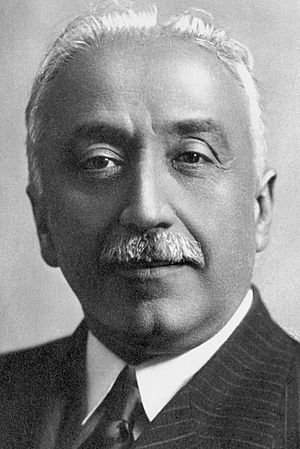

• 1931

|

Juan Bautista Aznar-Cabañas | ||||||

|

• Restoration Courts

|

Senate (Spain) | ||||||

| Congress of Deputies | |||||||

| History | |||||||

|

• Alfonso XII of Spain

|

November 15 1885 | ||||||

|

• Regency of Maria Christina of Habsburg

|

1885-1902 | ||||||

|

• Constitutional period of the reign of Alfonso XIII

|

1902-1923 | ||||||

|

• Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera

|

1923-1930 | ||||||

|

• Dictablanda of General Dámaso Berenguer

|

1930-1931 | ||||||

|

• Proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic

|

April 14 1931 | ||||||

| Currency | Peseta | ||||||

| ISO 3166 code | ES | ||||||

|

|||||||

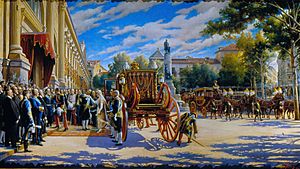

The reign of Alfonso XIII was a time in Spanish history when Alfonso XIII of Bourbon was king. He became king the moment he was born in May 1886. This was because his father, Alfonso XII, had passed away five months earlier.

While Alfonso XIII was a child, his mother, María Cristina de Habsburgo-Lorena, acted as the country's leader. She was the regent until May 1902. At age sixteen, Alfonso XIII officially became king. He took an oath under the Constitution of 1876. His personal rule lasted until April 14, 1931. On that day, he had to leave Spain after the Second Republic was declared.

His reign is usually divided into a few main parts:

- The regency of Maria Cristina of Habsburg (1885-1902) was a very important time. Spain's political system became stable. Liberal policies grew. But big problems also appeared. These included the loss of colonies after the Spanish-American War in 1898. Inside Spain, society changed a lot. New political ideas like regional nationalism and a strong workers' movement appeared.

- The constitutional period (1902-1923) was when Alfonso XIII ruled personally. He was supposed to follow the 1876 Constitution. But he often got involved in politics, especially military matters. This made it harder for Spain to become a true parliamentary monarchy.

- The dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (1923-1930) began when King Alfonso XIII allowed Primo de Rivera's coup d'état. This ended the liberal government. The king's future became tied to the dictatorship. When Primo de Rivera resigned in January 1930, the monarchy itself was in trouble.

- General Berenguer's dictablanda (1930-1931) could not stop the growing support for a republic. This led to the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic on April 14, 1931. Alfonso XIII had to go into exile. During his reign, Spain changed a lot. A strong workers' movement grew. Regional identities became more important. The economy became more protected. There were also attempts to modernize the political system.

Contents

- The Regency of Maria Christina (1885-1902)

- Alfonso XIII's Constitutional Reign (1902-1923)

- Early Years: Divided Parties and King's Influence (1902-1907)

- Antonio Maura's "Long Government" (1907-1909)

- Liberals in Power: Canalejas's Reforms (1909-1913)

- Conservatives Return: "Suitable" vs. "Maurists" (1913-1915)

- The Restoration Crisis (1914-1923)

- World War I's Impact on Spain

- Liberals Return and Social Conflict (1915-1917)

- The Crisis of 1917

- Escaping the 1917 Crisis: "Concentration Governments" (1917-1918)

- The "Regional Question"

- "Bolshevik Triennium" and "Social War" in Catalonia

- The "Annual Disaster" and Its Aftermath (1921-1922)

- Last Constitutional Government (December 1922-September 1923)

- The Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (1923-1930)

- General Berenguer's "Dictablanda"

- Responsibilities

- See also

The Regency of Maria Christina (1885-1902)

The "Pact of El Pardo" and Sagasta's Government (1885-1890)

King Alfonso XII died on November 25, 1885. His wife, María Cristina de Habsburgo-Lorena, became regent. The king had no sons, and his wife was pregnant. This caused much worry about the future of the Restoration government. Some feared that Carlists or Republicans might try to take power.

The leaders of the two main political groups, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo (Conservatives) and Práxedes Mateo Sagasta (Liberals), met. They agreed that Sagasta's party would take over the government. This agreement was called the "Pardo Pact." It helped keep the political system stable. The Conservatives agreed to let the Liberals introduce new laws. These laws would bring back freedoms from an earlier democratic period.

However, some Conservatives did not agree. They left their party to form a new one. They tried to create a middle ground between the two main parties.

In April 1886, the Liberals called for elections. They wanted to win a strong majority in Parliament. This period became known as Sagasta's Long Government or Long Parliament. It lasted almost five years. Many important reforms were made during this time. Some historians call it the "most fruitful period" of the Restoration.

The first big reform was the Law of Associations in June 1887. This law allowed people to form groups freely. It also made workers' organizations, like trade unions, legal. This greatly helped the workers' movement in Spain. Under this new law, anarchist and socialist groups grew. The socialist Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) was founded in 1888. The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) also held its first official meeting.

The second major reform was the law of the jury in April 1888. This law established trial by jury for certain crimes. These included crimes affecting social order or individual rights, like freedom of the press. The jury would decide the facts, and judges would apply the law.

The third big reform was universal (male) suffrage on June 30, 1890. This meant all men over twenty-five could vote, regardless of their income. This was a major political event. However, it did not make the system truly democratic. Electoral fraud continued. Local bosses, called caciques, still controlled elections. Governments were formed before elections, not after. The party in power always won. So, even with more people voting, the system did not change much. The Constitution was not fully reformed. Principles like national sovereignty and freedom of religion were still not fully recognized.

Electoral fraud continued because there were no rules to ensure fair voting. The Minister of the Interior, known as the "great elector," controlled the process. He made sure his party won. This political control from above was key to Spanish politics at the time.

Stability and New Challenges (1890-1895)

The early 1890s were a time of stability for the Restoration political system. The system of alternating power between Conservatives and Liberals worked well. But then, new problems appeared. These included issues with workers, the rise of regional nationalism, and the colonial question. These problems led to the Cuban War of Independence and later the Spanish–American War. This defeat marked a big crisis for Spain.

Cánovas del Castillo's Conservative Government (1890-1892)

After Sagasta's reforms, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo became prime minister in July 1890. His government kept the liberal reforms. This showed that the system was stable. The Conservatives respected the changes made by the Liberals. Cánovas's government oversaw the first elections with universal male suffrage in February 1891. The system of fraud still worked. The Conservatives won a large majority.

There were two main groups within the Conservative party. One group, led by Francisco Romero Robledo, focused on political control and winning elections. The other, led by Francisco Silvela, wanted reforms. Cánovas preferred Romero Robledo's approach. Silvela left the government in November 1891. His reform ideas would not be put into practice until after Cánovas's death and the "disaster of '98".

The most important action of this government was the Arancel Cánovas of 1891. This law ended free trade and put strong taxes on imported goods. This protected Spanish industries, like textile factories in Catalonia. It also followed a global trend towards protecting national economies. During this time, Spain celebrated 400 years since the discovery of America. Two other important events happened: the creation of the Unió Catalanista, a Catalan nationalist group, and the start of Basque nationalism with Sabino Arana's book.

Liberals Return and Anarchist Violence (1893-1895)

In December 1892, a corruption scandal in Madrid caused Cánovas's government to fall. The regent asked Sagasta to form a new liberal government. Sagasta called for new elections in March 1893. As expected, the Liberals won a huge victory.

Key figures in the new government were Germán Gamazo and his son-in-law Antonio Maura. Gamazo tried to balance the budget, but war spending in Melilla made it hard. Maura, as Minister of Overseas Territories, tried to give more self-rule to the Philippines. He also tried to do the same for Cuba. But his plans for Cuba failed. Some in Spain thought his ideas were unpatriotic. Maura and Gamazo resigned, causing a crisis in the government.

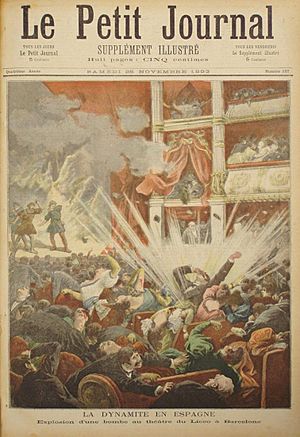

The government also faced "anarchist terrorism." This was a period of violence by anarchists. They believed it was a response to unfair society. Barcelona was a main target. On September 24, 1893, General Arsenio Martínez Campos was attacked. One person died. The attacker said it was revenge for harsh actions against workers in Jerez. In Jerez, workers were tortured and executed after an uprising. On November 7, a bomb was thrown into the Liceu Theatre in Barcelona. It killed 22 people and injured 35.

Crisis at the Turn of the Century (1895-1902)

The end of the 19th century brought a major crisis for the Restoration. The Cuban War of Independence started in February 1895. This led to Sagasta's liberal government falling. Antonio Cánovas del Castillo's conservative government took over. Anarchist violence also continued. On June 7, 1896, a bomb exploded during a procession in Barcelona. Six people died, and many were injured. The police response was very harsh. Many "suspects" were arrested and tortured in Montjuic Castle. This was known as the Montjuic trial. Many were sentenced to death or life in prison.

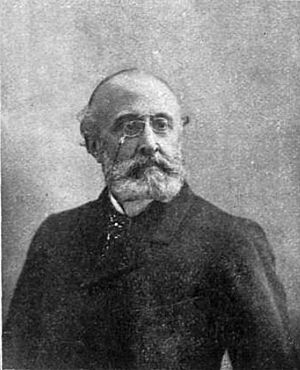

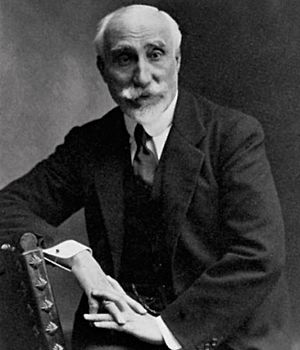

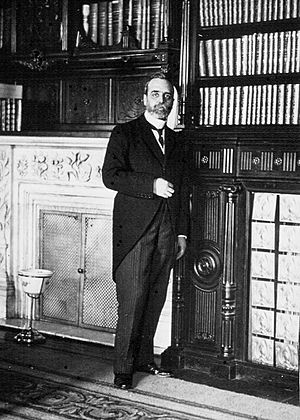

The Montjuic trial caused international outrage. There were doubts about the evidence, which came from confessions obtained through torture. A journalist named Alejandro Lerroux led a campaign against the government. In this tense atmosphere, the Prime Minister, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, was assassinated. An Italian anarchist killed him on August 8, 1897. Práxedes Mateo Sagasta then had to take over the government.

The Cuban War (1895-1898)

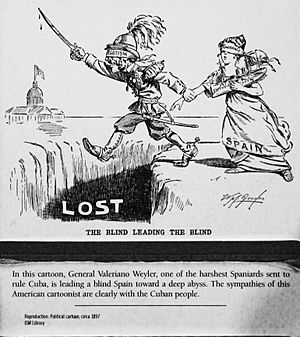

In February 1895, a new independence uprising began in Cuba. It was led by José Martí's Cuban Revolutionary Party. Spain sent many soldiers to the island. In January 1896, General Valeriano Weyler took command. He wanted to win the war at any cost. Weyler ordered Cuban villagers to move into areas controlled by Spanish forces. He also ordered the destruction of crops and livestock. This was to stop the independence fighters from getting supplies. These actions helped militarily but caused great human suffering. Many people died from disease and lack of food. Many peasants, with nothing left, joined the rebel army.

In 1896, another independence uprising began in the Philippines. It was led by the Katipunan group. This rebellion was stopped in 1897. General Polavieja used harsh methods, similar to Weyler's. José Rizal, a Filipino intellectual, was executed.

After Cánovas was killed in August 1897, Sagasta became prime minister in October. He dismissed General Weyler. He also tried to give Cuba more political self-rule. This was a last attempt to reduce support for the rebellion. But it was too late, and the war continued.

The Spanish-American War: The "Disaster of '98"

The United States had growing economic interests in Cuba. American public opinion also supported Cuban independence. The American press reported on Weyler's harsh actions. This led to an anti-Spanish campaign. The US wanted to intervene. American aid to Cuban rebels was crucial. In November 1896, Republican President William McKinley was elected. He wanted Cuba to be independent or annexed by the US. Spain refused to sell Cuba. So, the self-rule granted by Sagasta's government did not satisfy the US or the Cuban rebels.

In February 1898, the American battleship Maine sank in Havana harbor. An explosion killed many sailors. Two months later, the US Congress demanded Cuba's independence. President McKinley declared war on April 25.

The Spanish-American War was short and fought at sea. On May 1, 1898, Spain's fleet in the Philippines was destroyed. American troops then occupied Manila. On July 3, Spain's fleet near Santiago de Cuba was also sunk. A few days later, Santiago de Cuba fell to American troops. The Americans then occupied Puerto Rico.

Sagasta's government immediately sought peace talks. The Treaty of Paris was signed on December 10, 1898. Spain recognized Cuba's independence. It also gave Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam to the United States. The next year, Spain sold its remaining Pacific colonies to Germany.

Historians say the war was "absurd and useless." But Spanish leaders believed they had to fight to save the monarchy. They preferred losing Cuba in a war to losing the monarchy. After the defeat, Spanish pride turned into frustration. However, the political system managed to survive this crisis.

The "Regenerationist" Governments (1898-1902)

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were shaped by regenerationism. This idea called for Spain to "regenerate" itself. The goal was to prevent another "disaster of '98." Many writers explored why Spain was in such a "prostrate" state. They wondered what needed to be done. These writers included those of the Generation of '98.

Joaquín Costa was a very influential regenerationist writer. In 1901, he wrote Oligarquía y caciquismo. He argued that Spain's political system caused its "backwardness." To "regenerate" Spain, he said, an "iron surgeon" was needed. This person would end the corrupt system and focus on "school and pantry" (education and basic needs).

In March 1899, the new conservative leader, Francisco Silvela, became prime minister. He took over from Sagasta, who had led Spain during the "disaster." Silvela supported the calls for "regeneration." He described Spain as a country "without a pulse." He introduced reforms to address this. Silvela's plan was to use conservative reforms to protect national values during the crisis.

The most important reform was the tax reform by Finance Minister Raimundo Fernández-Villaverde. This reform aimed to fix the state's financial problems. The war had caused a huge increase in public spending. The reform tried to stop the value of the peseta from falling and prices from rising.

Silvela's government faced one major opposition movement. This was a "taxpayers' strike" in Catalonia in 1900. It was led by Joaquín Costa and business groups. They demanded political and economic changes. But the movement failed. Business leaders in the Basque Country and Catalonia ended up supporting Silvela's government.

Internal disagreements caused Silvela's government to fall in October 1900. General Marcelo Azcárraga Palmero succeeded him. His government lasted only five months. In March 1901, the liberal Sagasta returned as prime minister. This was the last government of María Cristina's Regency. It was also the first of Alfonso XIII's personal reign.

Alfonso XIII's Constitutional Reign (1902-1923)

Early Years: Divided Parties and King's Influence (1902-1907)

When Alfonso XIII became king in May 1902, he was sixteen. Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, the old leader of the Liberal Party, was prime minister. Sagasta left office in December and died a month later. Francisco Silvela, leader of the Conservative Party, took over. As was the custom, Silvela called for new elections in April 1903 to get a strong majority. Silvela promised fair elections, but still ensured a conservative win. Republicans did well in cities like Madrid and Barcelona. This caused more tension within the Conservative Party. Silvela, feeling tired, resigned.

After the old leaders were gone, different groups within the Liberal and Conservative parties fought for power. In the Conservative Party, Raimundo Fernández-Villaverde and Antonio Maura competed. Maura became prime minister in December 1903. The Liberal Party was even more divided, with five leaders wanting to replace Sagasta. This weakened both parties. The system of alternating power continued, but these years were very unstable. The Conservatives governed from 1903 to 1905, and the Liberals from 1905 to 1907. There were many government changes during this time.

The new king became more involved in politics. This caused problems between the Crown and the governments. Newspapers criticized the king's influence. In mid-1903, El Heraldo de Madrid wrote that it seemed the king's will was the only power. When Maura became prime minister, Republicans called it an "oriental crisis." They hinted that the queen mother, María Cristina de Habsburgo-Lorena, was involved.

Alfonso XIII's first major political intervention happened in December 1904. He refused to approve the appointment of the Army Chief of Staff. This forced Prime Minister Antonio Maura to resign.

The king's involvement became even clearer during the ¡Cu-Cut! incident. On November 25, 1905, army officers attacked the office of a Catalan satirical weekly, "¡Cu-Cut!". They were angry about a cartoon that made fun of the Spanish army's defeats. Another Catalan newspaper was also attacked. The liberal government of Eugenio Montero Ríos tried to control the military. But the king supported the army. This forced Montero Ríos to resign.

The new government, led by Segismundo Moret, was told by the king to prevent attacks on the army. Moret quickly passed a law called the "Law of Jurisdictions." This law gave military courts the power to judge crimes against the nation and the army.

Historians say this law gave the military too much power. It set a bad example of giving in to military demands. This greatly weakened civilian power. In response, a coalition of parties formed in Catalonia in May 1906. It was called Catalan Solidarity. It included Republicans and Catalan nationalists. This group had huge success. In the 1907 elections, they won 41 out of 44 seats in Catalonia. This showed that the "Catalan question" was a major problem for Spanish politics.

Antonio Maura's "Long Government" (1907-1909)

The Law of Jurisdictions caused a crisis in the Liberal Party. Segismundo Moret resigned in July 1906. After several unstable liberal governments, the King asked Antonio Maura, the Conservative leader, to form a government in January 1907. Maura, following tradition, dissolved Parliament and called new elections. The big news in these elections was the huge win for Catalan Solidarity in Catalonia.

From 1907 to 1909, Maura tried a "revolution from above." This meant reforming the political system from within the government. His main goal was to get popular support for the monarchy and end the cacique system (local boss rule). Maura believed that these reforms would help the monarchy, the Church, and the established social order.

His first reform was a new electoral law passed in August 1907. This law aimed to end electoral fraud. It put the Central Census Board in charge of elections. It also made voting compulsory. And if only one candidate ran in a district, they would automatically win.

However, Maura's goal of "honest" elections was not fully met. The system still allowed for fraud. For example, Article 29, which allowed automatic wins, was often used. In some elections, one-third of Parliament was chosen this way.

Maura also wanted to reform local government. He proposed giving more financial and administrative power to town councils and provincial councils. But he suggested a system where elections were based on groups, not individual votes. The Liberals opposed this, and the bill was not approved. Maura's government also promoted Spanish nationalism and protected national industries. He also introduced social laws, like Sunday rest and rules for women and child labor. He created the National Welfare Institute.

Public order was handled by the strict Minister of the Interior, Juan de la Cierva y Peñafiel. He proposed a law to stop terrorism. This law allowed the government to close newspapers and anarchist centers without a court order. Republicans and Socialists opposed this law. Liberals also joined the opposition. They formed a "Block of the Left" against Maura.

The event that finally brought down Maura's government was the Tragic Week in Barcelona. On July 9, 1909, workers building a railway in Melilla were attacked. The government sent army reinforcements, including reservists who were married and had children. This caused protests against the war in Morocco. On July 26, a general strike began in Barcelona. It spread to other Catalan cities. In Barcelona, there were anti-clerical riots. People blamed the Church for the country's problems.

During a week of riots, 104 civilians and 8 guards were killed. Many religious buildings were burned. The government's response was very harsh. 1700 people were arrested. Five people were executed, and many were imprisoned or exiled. The execution of anarchist teacher Francisco Ferrer Guardia on October 13 caused outrage across Europe.

The international protests were used by the Liberal Party and Republicans to campaign against Maura. The PSOE (Socialist Party) also joined this "Block of the Left." On October 18, 1909, a heated debate began in Parliament. The Minister of the Interior accused the Liberals of links to anarchists. Maura supported his minister. The liberal newspapers were furious. On October 22, Maura offered his resignation to the King, who accepted it. The King appointed Moret in his place.

Maura's removal was unusual. The opposition party had brought down the government using street protests and support from "anti-dynastic" parties. This broke the agreement that had kept the Restoration system working.

Liberals in Power: Canalejas's Reforms (1909-1913)

The government of the liberal Segismundo Moret did not last long. His attempts to work with Republicans caused a crisis in the Liberal Party. The King then appointed José Canalejas as the new prime minister in February 1910.

Canalejas wanted to "democratically regenerate" Spain. He believed the state should be the main force for modernization. He tackled many problems, including the "religious question." Canalejas, a Catholic himself, wanted a friendly separation of Church and State. He tried to reduce the power of religious orders. In December 1910, a temporary law called the Law of the Padlock was passed. It said no new religious orders could be established for two years. But this law had little effect. It was meant to be temporary until a new law on associations was passed, which never happened. Despite this, Canalejas was seen as an enemy of the Catholic religion.

The government was more successful with social reforms. Canalejas believed that labor conflicts should be solved through negotiation. He supported the Institute of Social Reforms, which mediated between workers and employers. He also passed laws to improve working conditions. He tried to pass a law on collective labor contracts, but it faced strong opposition.

During Canalejas's government, strikes increased. Workers' organizations grew stronger. Socialists, with Pablo Iglesias in Parliament, expanded rapidly. The UGT union grew, and the National Confederation of Labor (CNT) was founded in 1910. The government responded with a mix of negotiation and repression. For example, a revolutionary general strike in 1911 led to the CNT being dissolved.

Canalejas also addressed two long-standing popular demands. He abolished the "consumos" (taxes on basic goods), which made food more expensive. He also tackled military service inequality.

In 1912, compulsory military service was established for wartime. This ended the "redemption in cash" system, where wealthy families could pay to avoid service. In peacetime, a middle ground was found. "Quota soldiers" could pay to serve for a shorter time. Only sons of poor families were exempt.

Canalejas also addressed the Catalan question. He proposed creating a new regional body called the Commonwealth of Catalonia. This would unite the four Catalan provincial councils. It would be led by Enric Prat de la Riba. The project was approved by Parliament in June 1912. But Canalejas was assassinated before it was ratified by the Senate. It finally came into force in December 1913.

Canalejas successfully handled the Moroccan problem. In May 1911, Spain gained control of its "zone of influence." This allowed him to negotiate with France. The Spanish protectorate of Morocco was officially established. In November 1912, an agreement with France was reached. But on November 12, Canalejas was assassinated by an anarchist in Madrid.

Canalejas's death was very important for Spanish politics. It left the Liberal Party without a strong leader. The party became divided into factions. This contributed to the crisis of the Restoration political system.

Conservatives Return: "Suitable" vs. "Maurists" (1913-1915)

The Liberal Party's division led to the fall of the government led by the Count of Romanones. A group within his own party voted with the Conservatives to bring him down.

The King then appointed Eduardo Dato as prime minister. But Dato's Conservative Party was also divided. Its leader, Antonio Maura, no longer supported the system of alternating power. Maura believed that after Canalejas's assassination, the King should have appointed a Conservative government, not another Liberal one. In January 1913, Maura announced his resignation as head of the Conservative Party. He suggested forming a new "suitable" party to alternate with the Liberals.

Maura's criticism grew stronger. He attacked the Liberals. A part of his party, led by Eduardo Dato, disagreed with Maura. This split the party into "maurists" and "suitable ones." The "suitable ones" wanted to keep the system of alternating power with the Liberals. Maurism became a new Catholic and nationalist political movement. Dato managed to stay in power for two years. But Parliament was open for only seven months during this time.

Historians say that from 1913 to 1914, the parliamentary system entered a new crisis. The main parties were divided into factions. This made political rotation difficult. The system of alternating power, which had worked since 1885, was over. The King's role became more important. He acted as an "arbiter" between the factions. He also strengthened his ties with the army.

In this time of crisis, the Reformist Party appeared. It was led by Melquiades Álvarez. This party was made up of Republicans who were willing to accept the Monarchy if it became democratic. They wanted to be the new left-wing party in the system. Álvarez appealed to Republicans who believed that while a Republic was theoretically better, forms of government could change.

Young intellectuals joined the reformist movement. In October 1913, they launched the League of Political Education. Its manifesto was signed by important figures like José Ortega y Gasset. In March 1914, Ortega y Gasset gave a speech called Vieja y nueva política (Old and New Politics). He said the old system was exhausted and needed to be replaced. These intellectuals believed that renovation was possible without changing the regime. They hoped the Crown would use the crisis to open the door to new politics.

The Restoration Crisis (1914-1923)

World War I's Impact on Spain

World War I greatly affected Spain's political system. Food shortages, economic problems, poverty, and rising prices made people more politically active. The old system of local bosses and political control broke down. After the war, it was impossible to go back to the old ways. However, the war was not the direct cause of the two-party system's collapse. That system was already weakening.

When World War I began in August 1914, the conservative government of Eduardo Dato decided Spain would remain neutral. Most leaders agreed that Spain lacked reasons and resources to join the war. King Alfonso XIII also supported neutrality.

Neutrality had big economic and social effects. It boosted Spain's industrial production. New markets opened up in warring countries. But prices soared, and wages did not keep up. Basic goods, like bread, became scarce. This led to food riots and more labor conflicts. The two big unions, CNT and UGT, demanded higher wages.

Liberals Return and Social Conflict (1915-1917)

Following the system of alternating power, the liberal Count of Romanones replaced Eduardo Dato as prime minister in December 1915. He won a large majority in the next elections. His government faced growing social unrest led by the CNT and UGT. In May 1916, both unions agreed to work together. They called a general strike for December 18 to protest rising prices. The strike was successful. So, in March of the next year, they planned another, "revolutionary" strike. Its goal was to completely change Spain's economic and political system.

In April 1917, the liberal Romanones government fell. He was seen as too pro-Allies in the war. Manuel García Prieto replaced him. But his government lasted only three months. It faced a serious crisis caused by the new Defence Juntas.

The Crisis of 1917

The 1917 crisis was the worst for the Restoration's constitutional system. It started with the "Juntas de Defensa" (Defense Juntas). These were groups of army officers who formed in 1916. They demanded higher salaries because of inflation. They also protested against quick promotions for officers in Morocco.

The Juntas wanted to be legally recognized. The Romanones government opposed this. The next government, led by Manuel García Prieto, ordered the Juntas to dissolve. But the King sided with the Juntas. He forced García Prieto to resign. A conservative government under Eduardo Dato was formed. Dato quickly gave in to the Juntas' demands. This repeated what happened in 1905-1906 with the ¡Cu-Cut! incident. The military appealed to the King, and he again supported them. This led to the "Law of Jurisdictions." Dato's government suspended constitutional rights, censored the press, and accepted the Juntas' rules. He also closed Parliament.

In this political crisis, Catalan leader Francesc Cambó took action. On July 5, he gathered Catalan deputies and senators in Barcelona. They demanded that Catalonia become an autonomous region. They also wanted Parliament to reopen as a constituent assembly. If the government refused, they would call an Assembly of Parliamentarians on July 19. The government tried to discredit this meeting as "separatist." Only Catalanist, Republican, Reformist, and Socialist deputies attended. They agreed to form a government that would represent the country's will. This government would call elections for a constituent assembly. The Assembly was dissolved by the governor, and participants were briefly arrested.

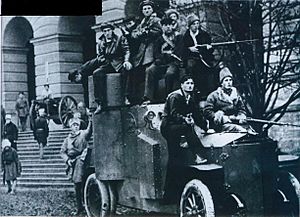

Meanwhile, workers' organizations prepared for a general strike. The Socialists decided to call it on their own. They wanted to overthrow the Monarchy and form a provisional government. The CNT, being "apolitical," stayed out.

The strike failed. It only had some support in major cities and industrial areas. It had no impact in the countryside. Catholic unions condemned the strike. Young monarchists volunteered to keep services running. The Defence Juntas, which Socialists thought would support them, sided with the government. They helped repress the strike.

The repression resulted in 71 deaths, 200 wounded, and over 2,000 arrests. Members of the strike committee were arrested. The 1917 crisis ended any further revolutionary attempts. Catalan nationalists, reformists, and even radicals backed down. The republican-socialist alliance broke apart. Socialism faced internal divisions. Anarcho-unionism became more anti-political. The Restoration regime, despite being thought dead, showed surprising strength. It lasted six more years.

Escaping the 1917 Crisis: "Concentration Governments" (1917-1918)

On October 30, the Assembly of Parliamentarians met in Madrid. Cambó, the leader, pushed for an end to the system of alternating power. The King met with Cambó. He proposed a broad government that would ensure fair elections. Cambó told the parliamentarians that the King agreed with their proposals.

On November 1, 1917, a "concentration government" was formed for the first time. It included conservatives, liberals, and the Catalan Lliga. Manuel García Prieto was prime minister. This government called the elections of February 1918. They were supposed to be "clean," but the old system of local bosses still worked. The elections showed the dynastic parties were still divided. No group had a clear majority. Cambó called the result "a disaster." He said it showed that the old parties could not create a strong Parliament.

The "concentration government" lasted only a few months. A strike by civil servants, who formed their own juntas, ended it. The King then asked the Count of Romanones to gather all the liberal and conservative leaders. On March 20, 1918, at the Royal Palace, Alfonso XIII threatened to abdicate if they did not form a "concentration government." This government would be led by Antonio Maura.

This led to the "National Government." It included all the leaders of the dynastic groups, plus Francesc Cambó. The new government pardoned the imprisoned Socialist leaders. They could now take their seats in Parliament. The government also passed a law about civil servants' jobs and promotions. This ended the practice of "cesante" (officials being dismissed when a new government came to power). However, the government failed to approve the state budget. Maura resigned in November 1918.

After the failure of these "concentration governments," the system of alternating power between conservatives and liberals resumed. But political stability was not achieved. Seven governments followed each other in two and a half years.

The "Regional Question"

Maura's "National Government" was followed by a liberal government on November 10, 1918. It was led by García Prieto, with Santiago Alba as Finance Minister. This government faced a serious food supply problem and rising prices. Alba's reforms met resistance from industries that had profited from Spain's neutrality in the war. Protests against high prices increased. The Lliga, demanding autonomy for Catalonia, brought down the government in just one month. The King then asked the Count of Romanones to form a government. His main task was to handle the autonomy issue smoothly.

Cambó and the Lliga launched a campaign for "full autonomy" for Catalonia. This shook Spanish politics. The King initially supported it. He hoped it would keep Catalan people from revolutionary ideas. Cambó believed "Catalonia's time had come."

The idea of a Statute of Autonomy for Catalonia caused a strong reaction from Spanish nationalists. They launched an anti-Catalan campaign. Thousands protested in Madrid and other cities.

On December 2, 1918, Castilian provincial councils met in Burgos. They issued the Message from Castile. They defended Spanish "national unity." They opposed any region getting autonomy that would weaken Spanish sovereignty. They even called for a boycott of Catalan businesses. They also opposed Catalan being an official language. Only the Basque Country and Galicia showed support for Catalan nationalists.

The King changed his mind. He supported the "patriotic gestures of the Castilian provinces." In Parliament, Niceto Alcalá Zamora accused Cambó of wanting to be both Catalonia's Simón Bolívar and Spain's Otto von Bismarck. Conservative leader Antonio Maura also opposed Catalan autonomy. He told Catalan deputies they were Spaniards whether they liked it or not. His speech was widely applauded. On December 12, 1918, Cambó wrote to the King. He explained why most Catalan deputies and senators left Parliament in protest. Back in Barcelona, Cambó declared, "Monarchy? Republic? Catalonia!"

Romanones formed a commission to draft an autonomy proposal. It was chaired by Antonio Maura. The draft was very limited. It even removed some powers the Mancomunitat de Cataluña already had. This was unacceptable to Catalan deputies. Cambó asked for a vote in Catalonia to see if citizens wanted autonomy. But the dynastic parties delayed the debate. The government closed Parliament on February 27, using the La Canadenca strike in Barcelona as an excuse.

The Catalan autonomy campaign found strong support from Basque nationalism. Basque nationalism was at its peak. In 1918, the PNV won elections in Biscay. They also demanded "integral autonomy" for the Basque Country. The three Basque provincial councils demanded a return to old rights or broad autonomy. This proposal was rejected in Parliament.

From 1920, the Basque Nationalist Communion lost electoral support. Monarchist parties formed an anti-nationalist front. This front won the 1920 and 1923 elections. Basque nationalists lost their majority in the Vizcaya Provincial Council and the mayoralty of Bilbao.

"Bolshevik Triennium" and "Social War" in Catalonia

In addition to regional issues, a serious social crisis erupted in Catalonia and rural Andalusia. A "social war" with anarchist attacks and employer-hired gunmen broke out in Catalonia. In Andalusia, there were three years of protests by farm laborers. They were inspired by the Russian revolution.

The triumph of the October Revolution in Russia had a big impact on the Spanish workers' movement. However, neither the CNT nor the PSOE joined the Communist International. Only a small group of socialists left in 1921 to form the Communist Party of Spain. But the October Revolution inspired workers in Spain. In Andalusia, from 1918 to 1920, farm laborers' protests intensified. This period is known as the "Bolshevik triennium." There were constant strikes. Employers and authorities responded very harshly. Workers demanded higher wages and jobs for the unemployed. Protests included rallies and pamphlets. During strikes, laborers occupied farms. They were violently removed by the civil guard and army. There were also acts of sabotage and attacks. The peasant unrest in Andalusia decreased by 1920 due to repression.

Meanwhile, Catalonia experienced a "social war." The conflict began in February 1919 with the La Canadenca strike. This left Barcelona without electricity, water, and streetcars. The Romanones government tried to negotiate. But employers demanded a tough response. They found allies in the Captain General of Catalonia, Joaquín Milans del Bosch, and King Alfonso XIII. Services were militarized, and Barcelona returned to normal. But prisons filled with striking workers.

An agreement was reached between the company and workers, thanks to CNT leader Salvador Seguí. But the imprisoned strikers, under military law, remained. Milans del Bosch refused to release them. So, the CNT declared a general strike. Employers responded with a lock-out, leaving workers without income. The government tried to dismiss Milans, but the King opposed it. Romanones resigned. The conservative Antonio Maura replaced him. Maura approved Milans del Bosch's policy. The CNT was dissolved, and its leaders were imprisoned. The Somatén (a local armed force) helped maintain order in Barcelona.

The Catalan workers' conflict turned into a "social war." Both sides used violence in Barcelona. Unionists and employer-hired gunmen clashed. The latter were led by Manuel Bravo Portillo, who formed a gang of criminals. They carried out the first assassinations of CNT members. Anarchist "action groups" also formed. Their members carried out attacks against businessmen, police, and other workers. Buenaventura Durruti was a notable figure among them.

Maura called elections in June 1919. But he did not win a majority. Other conservative groups refused to recognize him as leader. This led to Maura's fall. Joaquín Sánchez de Toca, another conservative, succeeded him in August 1919. He tried negotiation to end the "social war." But his government also fell. Manuel Allendesalazar Muñoz, a conservative, replaced him. He returned to a "tough hand" policy. Allendesalazar's government also did not last long. In May 1920, Eduardo Dato replaced him. Dato dissolved Parliament and called new elections for December 1920.

Dato initially promoted negotiation. But after the assassination of the Count of Salvatierra by anarchists, he returned to repression. He appointed General Severiano Martínez Anido as civil governor of Barcelona. Martínez Anido applied harsh anti-union repression. This included the "ley de fugas" (law of escape), where prisoners were shot while supposedly trying to escape. This decimated the CNT. But it also increased violence. "Free Trade Unions," made up of Catholic workers, grew. They were preferred by employers. This led to competition and shootouts between unions.

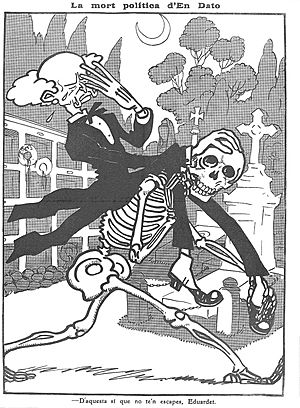

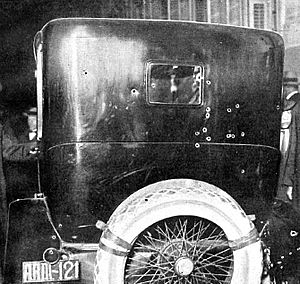

The violence escalated. On March 8, 1921, Eduardo Dato was assassinated in Madrid by anarchists. Dato's death led to more repression against the CNT. Violence between anarchists and "Free Trade Unions" continued. In 1923, Salvador Seguí, a CNT leader who opposed violence, was assassinated. The archbishop of Zaragoza, Juan Soldevilla, was also killed.

Attacks peaked in 1921. There were 87 attacks in 1919, 292 in 1920, 311 in 1921, 61 in 1922, and 117 in 1923. Fatalities included unionists, employers, police, and members of free unions.

The "Annual Disaster" and Its Aftermath (1921-1922)

After World War I, Spanish governments wanted to fully control the Moroccan protectorate. General Dámaso Berenguer was appointed High Commissioner in 1919. General Manuel Fernández Silvestre led the advance in the eastern zone from Melilla. He used small forts and met no resistance. In December 1920, he reached Annual. Berenguer and Silvestre met in March 1921 and decided to stop the advance. Spanish troops were spread out, with supply problems, and vulnerable to attack. Annual was the most advanced post.

After a leave in Madrid, Silvestre resumed the advance in May 1921. But this time, he met resistance from Rifian tribes led by Abd el-Krim. Silvestre asked for reinforcements, but they did not arrive. On July 19, he ordered to retake Annual. Silvestre arrived with 4,500 men but had to retreat from Annual. The High Commissioner promised reinforcements, but they were too late.

The "disaster of Annual" was a huge defeat. The Spanish army collapsed and retreated towards Melilla. Many soldiers died, including General Silvestre. Over 10,000 soldiers were killed.

This disaster shocked the public. People demanded accountability. King Alfonso XIII was accused of encouraging Silvestre's reckless actions. Socialist deputy Indalecio Prieto made a strong accusation in Parliament. He said that 8,000 dead soldiers demanded justice. The King turned to Antonio Maura to deal with the crisis. On August 3, 1921, Maura formed another "concentration government." It included conservatives, liberals, and Cambó. One of its first actions was to investigate the military responsibilities for the disaster. General Juan Picasso led the investigation. A military operation was also launched to retake lost territory in Morocco. Maura's government lasted only eight months. In March 1922, José Sánchez Guerra formed a new conservative government.

Sánchez Guerra tried to limit military involvement in politics. He wanted to put the Defence Juntas under civilian control. The King supported him. In June 1922, the King told military officers in Barcelona that they should not get involved in politics. In November 1922, Parliament passed a law dissolving the "informative commissions" (the Juntas). It also set strict rules for military promotions. This helped reunite the army. General Severiano Martínez Anido was removed from his post in Barcelona.

General Picasso's report on the "disaster of Annual" was devastating. It exposed fraud and corruption in Morocco. It also criticized the lack of preparation of military commanders. Based on the Picasso File, 36 officers and generals were prosecuted.

When the issue was debated in Parliament, socialist deputy Indalecio Prieto again made strong accusations. He blamed the Minister of War and especially the King for what happened. Prieto said that all parties had failed to keep the King within his constitutional duties. The debate on responsibilities showed the division among conservatives. This led to the fall of the government. In December 1922, a new "liberal concentration" government was formed. It was led by Manuel García Prieto. This would be the last constitutional government of the reign of Alfonso XIII.

Last Constitutional Government (December 1922-September 1923)

The "liberal concentration" government, led by Manuel García Prieto, wanted to continue the investigations into responsibilities. In July 1923, the Senate allowed General Berenguer to be prosecuted. The government also tried to strengthen civilian power over the military in Catalonia and Morocco. It proposed a big reform to create a true parliamentary monarchy. However, the elections in early 1923 still had widespread fraud. But anti-system parties, especially the PSOE, gained ground. The government could not carry out its reforms. On September 13, 1923, General Miguel Primo de Rivera, Captain General of Catalonia, led a coup d'état in Barcelona that put an end to the liberal regime of the Restoration. King Alfonso XIII did not oppose the coup.

The Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (1923-1930)

A "Dictatorship with a King"

On September 13, 1923, General Miguel Primo de Rivera led a coup d'état in Barcelona. This started the "dictatorship with a King." This term means that King Alfonso XIII allowed Primo de Rivera's military coup to succeed. He gave power to the general. This was similar to what happened in Italy a year earlier with Mussolini. Alfonso XIII even said he had "my Mussolini."

After accepting the coup, Alfonso XIII no longer acted as a constitutional monarch. He became the head of state for a new "dictatorship with a King." The presidents of the Senate and Congress reminded the King that the Constitution required him to call elections. But the King did not. Primo de Rivera dismissed them. He said the country wanted "order, work, and economy," not "liberal and democratic essences."

At first, the Dictatorship was supposed to be temporary. Primo de Rivera said it would last only "ninety days" to "regenerate" the country. But it lasted for six years and four months.

The Military Directory (1923-1925)

Restoring "Social Peace"

The first action of the Directory was to replace provincial and local officials with military officers. Their main job was to restore public order. They declared a state of war. This suspended constitutional rights like freedom of assembly. Military courts judged "political crimes." Another early decision was to extend the Catalan Somatén (a local armed force) to all of Spain.

The state of war brought "social peace." Violence almost disappeared. The number of strikes also decreased. This was helped by the economic growth of the "roaring twenties."

The Dictatorship treated the two large workers' organizations differently. Primo de Rivera tried to attract the Socialists. This caused a split within the Socialist Party. Some, like Julián Besteiro and Francisco Largo Caballero, favored working with the Dictatorship. Others, like Indalecio Prieto, opposed it. The pro-collaboration group won. Socialists joined the Labor Council. Largo Caballero even joined the Council of State. On the other hand, the Dictatorship repressed the CNT. The anarchist organization went underground.

Ending "Caciquismo"

Primo de Rivera saw himself as the "iron surgeon" who would end "caciquismo" (local boss rule). Besides restoring order, the military authorities were to "regenerate" public life. They would end the corrupt system of local bosses. New military civil governors investigated corruption. They even accepted anonymous complaints. Military delegates were appointed in each judicial district.

However, this measure was "not very effective." Some delegates were corrupt themselves. Many former local bosses joined the Dictatorship's party, the Patriotic Union. This allowed new forms of local boss rule to emerge.

Political reform at the local level ended with the Municipal Statute of 1924. This law stated that a democratic state needed free municipalities. But mayors were still appointed by the government, not elected.

Another step to end "caciquismo" was dissolving provincial councils in January 1924. The King's civil governors appointed new members. This angered the Regionalist League of Catalonia. They had initially supported Primo de Rivera. But the new appointees in Catalonia were "Spanishists" who opposed regionalism.

The Patriotic Union: An "Apolitical" Party

In early 1924, the idea grew that a "new politics" was needed. This new politics would rely on "people of solid ideas" to form a "political party, but apolitical." This party would focus on administration, not traditional politics.

This is how the Patriotic Union was born in April 1924. Primo de Rivera called it a "central, monarchical, temperate and serenely democratic party." Later, it adopted the motto: "Nation, Religion and Monarchy." One of its thinkers, José María Pemán, said it was different from fascism. He said it defended a "traditional social-Christian" state. He also rejected universal suffrage. The party was made up of traditional Catholics, "maurists," other conservatives, and opportunists.

The Patriotic Union was created and controlled by the government. It used funds from the government. Its newspaper, La Nación, helped bind the party.

However, the Patriotic Union did not effectively end "caciquismo." Many former local bosses joined its ranks. It even allowed new forms of local boss rule.

Spanish Nationalism and Fighting "Separatism"

Primo de Rivera's coup manifesto mentioned "shameless separatist propaganda" as a reason for his actions. Five days later, a decree was issued against "separatism." It punished "crimes against the security and unity of the Homeland" severely. Military courts judged these crimes. The Dictatorship promoted a strong Spanish nationalism. Symbols and groups related to other nationalisms were persecuted. Censorship limited publications in other languages. Political activities were restricted. Regional nationalisms were suppressed until 1929.

In Catalonia, it soon became clear that the Regionalist League had been wrong to support Primo de Rivera. He immediately began persecuting Catalan nationalism. Catalan was banned in official acts. Attempts were made to stop its use in sermons. Spanish was made the only administrative language. Catalan place names were changed to Spanish. The Jocs Florals were boycotted. Raising the Catalan flag was forbidden. Dancing sardanas (a Catalan dance) was limited. Professional and sports groups were persecuted for using Catalan. This caused many conflicts with Catalan institutions. Many were temporarily or permanently closed.

In January 1924, Primo de Rivera met with Catalan political leaders. Only the "Spanishist" National Monarchist Union supported him. Its leader, Alfonso Sala Argemí, became president of the Mancomunitat after Puig i Cadafalch resigned. But Sala eventually clashed with the military authorities. When the Provincial Statute was approved in March 1925, which effectively banned the Mancomunitat, Sala resigned.

After the Mancomunitat disappeared, Primo de Rivera's statements against Catalan culture and language became harsher. He completely opposed any regional autonomy. He offended not just political groups but all of Catalan society. This led to growing distance between Catalonia and the Dictatorship. Conflicts increased. Acció Catalana took the "Catalan case" to the League of Nations. Francesc Macià, a former military man and founder of Estat Catalá, became a symbol of Catalan resistance.

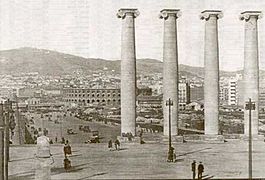

-

The four columns representing the four bars of the Catalan flag. Designed by Puig i Cadafalch for the International Exposition of Barcelona (1929).

-

The four columns today, seen from the National Palace of Montjuic.

Pacifying Morocco

General Primo de Rivera had always wanted to leave Morocco. He ordered troops to withdraw to the coastal area of the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco. This angered the "Africanist" sector of the Army. These officers had gained quick promotions for "war merits" in Africa. Lieutenant Colonel Francisco Franco was one of them. He had risen quickly from lieutenant to commander. He wrote articles defending Spanish colonialism. When Primo de Rivera decided to resume the war in Morocco, Franco and other "Africanist" officers became strong supporters of the Dictatorship. Franco was promoted to colonel and then general at age 33.

In March 1924, Primo de Rivera ordered a troop withdrawal from Yebala and Xauen. The withdrawal was difficult due to bad weather. Abd el-Krim, leader of the self-proclaimed Republic of the Rif, took advantage. He launched an offensive. The operation was a disaster. There were more casualties than in the Annual disaster three years earlier. Abd el-Krim seized much of the Spanish protectorate. Primo de Rivera hid the extent of the disaster using censorship. But in October 1924, he took personal command as Spanish High Commissioner in Morocco. The Rifian rebels made a mistake by attacking French positions in spring 1925. This allowed Primo de Rivera to save the situation.

Abd el-Krim's attack on French Morocco led France to cooperate with Spain. This led to the Al Hoceima landing in September 1925. It was a success. It caught the enemy from behind and split the rebel-controlled area. In April 1926, Abd el-Krim sought negotiations. The following year, Morocco was completely pacified. Abd el-Krim surrendered to the French and was exiled.

The victory in Morocco was a major triumph for Primo de Rivera's government. It set the stage for the Dictatorship's foreign policy. Primo de Rivera decided to stay in power after 1925. He had solved a problem that had plagued Spain since 1898. The issue of responsibilities for the Annual disaster was dropped.

The Civil Directory (1925-1930)

The Birth of the Civil Directory

The success in Morocco made Primo de Rivera popular. This allowed him to continue his regime. He returned the army to the barracks and began a civilian phase of the Directory. On December 13, 1925, Primo de Rivera formed his first civilian government. However, key positions were still held by military personnel. Primo de Rivera announced his intention to keep the Constitution suspended. He would not call elections.

With the Civil Directory, Primo de Rivera brought back the Council of Ministers. It had traditional roles and was half civilian, half military. Civilians belonged to the Patriotic Union. Key ministers included José Calvo Sotelo (Finance), Eduardo Aunós (Labor), and the Count of Guadalhorce (Public Works). Another important minister was the conservative José Yanguas Messía.

Historians note that Primo de Rivera showed his will to stay in power. He did not set a clear path for ending the dictatorship.

Failed Institutionalization

The first step to making the regime permanent was founding the "single party," the Patriotic Union, in April 1924. The second was forming the "Civil Directory" in December 1925. Next steps included creating the National Corporate Organization and calling the National Consultative Assembly. This Assembly was supposed to draft a new Constitution.

Primo de Rivera promised to improve workers' conditions. In November 1926, he created the National Corporate Organization (OCN). This body would regulate relations between workers and employers, supervised by the State. It was promoted by Labor Minister Eduardo Aunós. The OCN was inspired by Catholic social teachings and Fascist corporate models. Its goal was to ensure social peace.

The OCN had three levels: joint committees, provincial mixed commissions, and corporation councils. Employers and workers had equal representation. A government representative led each level. Primo de Rivera offered the socialist union, the UGT, a role in the OCN. The UGT accepted, which caused a major split among socialists. Some leaders, like Indalecio Prieto, opposed this collaboration.

On September 13, 1926, the third anniversary of his coup, Primo de Rivera held an informal plebiscite. He wanted to show popular support. This would pressure the King to accept his plan for an unelected Consultative Assembly. For a year, Alfonso XIII resisted. But in September 1927, he signed the call for the National Consultative Assembly. This Assembly was to prepare a new general legislation. It was not meant to be a Parliament or to legislate. It was a "body of information, controversy and advice." Most of its nearly 400 members were appointed by the government.

A setback for Primo de Rivera was the socialists' refusal to join the Assembly. They opposed it because posts were assigned, not elected. Even when Primo de Rivera allowed UGT elections, they still refused. Universities, increasingly against the regime, also did not send representatives.

The Assembly's first section presented a draft "Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy" in summer 1928. It was very authoritarian. It limited rights and did not separate powers. Only half of the single chamber was elected by universal suffrage. The other half was appointed by "corporations" and the King. The draft did not satisfy anyone, not even Primo de Rivera. It gave too much power to the Crown. A year later, the draft was stalled. The political debate shifted to creating a true "constituent period."

The Dictatorship failed to find a new institutional form. This ultimately led to its downfall.

Foreign Policy

The success in pacifying Morocco encouraged a more "aggressive" foreign policy. Primo de Rivera demanded that Tangier, a Moroccan city with many Spanish residents, be part of the Spanish Protectorate. Mussolini supported him. This made France and Great Britain suspicious. Primo de Rivera also demanded a permanent seat on the League of Nations Council. He threatened to withdraw if he didn't get it. But he achieved neither goal. Tangier kept its international status, and Spain did not get a permanent seat.

These failures led Primo de Rivera to focus on Portugal and Hispanic America. The Dictatorship sponsored the flight of the Plus Ultra seaplane. It flew from Spain to Buenos Aires in January 1926. The Ibero-American Exposition of Seville in 1929 also aimed to strengthen ties with American republics.

Economic Policy

The Dictatorship highlighted its economic achievements. The "Roaring Twenties" (a time of global economic growth) contributed to Spain's growth. Primo de Rivera's economic policy involved more state control. The Council of National Economy, created in 1924, regulated new industries. The government also protected "national production." Two important achievements were the creation of CAMPSA (oil monopoly) in June 1927 and the Compañía Telefónica Nacional de España (national telephone company). The Dictatorship's intervention was most visible in public works. This included hydraulic works, roads, and railroads. Electricity was also brought to rural areas. This economic nationalism and interventionism were traditional in Spain. Primo de Rivera simply took them to their extreme.

To pay for the increased public spending, the Dictatorship did not raise taxes. Instead, it issued Debt. This led to heavy foreign and domestic debt. It put the stability of the peseta at risk.

The Fall of the Dictatorship

The Dictatorship began to decline in mid-1928. Primo de Rivera's diabetes worsened. The regime failed to establish a new system. Opposition grew, including from parts of the Army. The Dictatorship had presented itself as "temporary." But by late 1927, it was clear Primo de Rivera intended to stay.

Social and political groups that had supported the Dictatorship gradually withdrew their support. Peripheral nationalisms were disappointed by the failure of "decentralization." Business organizations were unhappy with the UGT's "interference." Intellectuals and university students became disillusioned. Various liberal groups saw the Dictatorship trying to stay in power permanently. The King began to worry that his Crown was at risk if he remained tied to the dictator.

The conflict between the Dictatorship and intellectuals began in 1924. Primo de Rivera punished professors who supported Miguel de Unamuno. Unamuno had been dismissed and exiled for criticizing the regime. Student protests grew. The Dictatorship responded by expelling and exiling students. These student movements were led by the Federación Universitaria Escolar (FUE), founded in 1929.

In the Army, the main conflict was with the Artillery Corps. They disagreed with the Dictatorship's promotion system. Primo de Rivera suspended and then dissolved the Artillery Corps. Alfonso XIII tried to mediate, but Primo de Rivera refused. The King's final acceptance of the disbandment was seen by artillerymen as cooperation between Alfonso XIII and Primo de Rivera. This led to many in the army becoming republican. It also increased the distance between the army and the King.

There were also attempted coups. The Prats de Molló plot was a failed invasion of Spain from France. It was led by Francesc Macià and his party Estat Catalá, with help from Catalan anarcho-syndicalist groups.

As the Dictatorship lost support, opposition groups grew. Some members of the old parties, like the conservative José Sánchez Guerra, opposed the Dictatorship. Sánchez Guerra went into exile and later participated in a failed coup in January 1929. The old Conservative Party and Liberal Party had almost disappeared. Some joined the Unión Patriótica. Others, like Sánchez Guerra, joined the Constitutional Bloc, which called for the King's abdication. Some, like Niceto Alcalá-Zamora and Miguel Maura Gamazo, openly joined the Republican side.

Republicans gained strength with Manuel Azaña's new Republican Action Group. They formed the "Republican Alliance" in February 1926. This alliance included old parties like Alejandro Lerroux's Radical Republican Party and new ones. The Alliance helped renew republicanism. It attracted urban middle and lower-middle classes, as well as workers.

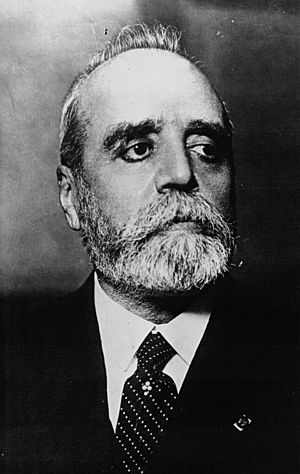

Facing declining support, Primo de Rivera tried to strengthen his position with the Crown and the Army. But the generals' response was lukewarm. He resigned to the King in January 1930, and his resignation was accepted. Alfonso XIII, who had been a King without a Constitution for six years, appointed General Dámaso Berenguer as prime minister. His goal was to return to constitutional rule. Primo de Rivera left Spain and died shortly after in Paris.

General Berenguer's "Dictablanda"

The King asked General Berenguer to return to "constitutional normality." But this was difficult. The King and his government made a mistake by trying to go back to the situation before Primo de Rivera's coup. Since 1923, Alfonso XIII had been a King without a Constitution. His power had come from the coup, not the Constitution. The Monarchy was now linked to the Dictatorship. It tried to survive after the Dictatorship fell.

General Berenguer struggled to form a government. The old dynastic parties had almost disappeared after six years of dictatorship. Most politicians refused to cooperate. So, Berenguer could only rely on the most conservative group. The Monarchy had no political organization to lead the transition.

Berenguer's policies also did not help save the Monarchy. The slow pace of reforms made people doubt if the government truly wanted to restore constitutional rule. The press started calling the new government a "dictablanda" (soft dictatorship). Some politicians called themselves "monarchists without a king." Others, like Niceto Alcalá-Zamora and Miguel Maura, joined the republican side.

Throughout 1930, it became clear that returning to the pre-1923 situation was impossible. The Monarchy was isolated. Its traditional supporters, like employers, began to abandon it. The Monarchy also lost the support of the middle class. Intellectuals and university students openly rejected the King.

The Catholic Church was one of the few remaining supporters. It was grateful for its restored position in society. But it was on the defensive against the rising tide of republicanism and democracy. The Army, too, had internal divisions. Loyalty to the King was cracking in some parts.

Social changes over the past thirty years were not favorable to restoring the old system. The link between the Dictatorship and the Monarchy led to a rapid rise of republicanism in cities. People concluded that Monarchy meant despotism, and democracy meant Republic. In 1930, hostility to the Monarchy spread. People cheered for the Republic in rallies. Intellectuals also joined the republican cause.

On August 17, 1930, the Pact of San Sebastián took place. Republican leaders met to plan how to end the Monarchy and proclaim the Second Spanish Republic. The meeting included leaders from various republican parties. Indalecio Prieto and other socialists also attended.

In October 1930, the two socialist organizations, the PSOE and the UGT, joined the Pact in Madrid. They planned a general strike and a military insurrection to overthrow the Monarchy. A "revolutionary committee" was formed to lead the action. The CNT, with its anti-political ideology, did not join.

The revolutionary committee prepared the military uprising and general strike. They believed that the Dictatorship had legitimized using force to change a regime.

However, the general strike was never declared. The military uprising failed because captains Fermín Galán and Ángel García Hernández revolted in Jaca three days early, on December 12. These events are known as the Jaca Uprising. The two captains were shot. This event greatly moved public opinion. They became "martyrs" for the future Republic.

Admiral Aznar's Government and the Monarchy's Fall

Despite the failure of the republican movement, General Berenguer had to act. He restored public freedoms and called general elections for March 1, 1931. The goal was to restore the constitutional system. But this was not a call for a constituent assembly to reform the Constitution. So, the call found no support, not even among monarchists.

On February 13, 1931, King Alfonso XIII ended Berenguer's "dictablanda." He appointed Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar as the new prime minister. Aznar formed a "monarchist concentration" government. It included old leaders from liberal and conservative parties. The government proposed new elections: municipal elections on April 12, followed by elections for a Constituent Parliament. This Parliament would revise the powers of the state and address the problem of Catalonia.

On March 20, during the election campaign, the "revolutionary committee" leaders were tried by court martial. The trial became a public display of republican support. The accused were released.

Everyone saw the municipal elections of April 12, 1931 as a vote on the Monarchy. The republican-socialist candidates won in 41 of the 50 provincial capitals. This was the first time a government was defeated in an election in Spain. Although monarchists won in rural areas due to the old system of local bosses, the revolutionary committee declared the results "unfavorable to the Monarchy" and "favorable to the Republic." They announced their intention to establish the Republic. On Tuesday, April 14, the Republic was proclaimed from city hall balconies. King Alfonso XIII was forced to leave the country. That same day, the revolutionary committee became the First Provisional Government of the Second Spanish Republic.

Responsibilities

One of the first decisions of the Constituent Courts, formed after the June 1931 elections, was to create a Commission of Responsibilities. This commission would continue the work of the one stopped by Primo de Rivera's coup in 1923. It would also investigate the responsibilities of the Dictatorship and the deposed King Alfonso XIII. The commission's powers were debated in August 1931. A law was passed defining its scope. It would investigate "high political or ministerial management responsibilities" that harmed the nation. This included the Annual Disaster, social policy in Catalonia, the 1923 coup, the Dictatorship's actions, and the Jaca Process. The commission would propose who was responsible and which court should punish them.

In the early morning of November 20, 1931, Parliament declared the "former King of Spain" guilty of "high treason." They said he had violated the Constitution. The "sovereign Court of the Nation" declared D. Alfonso de Borbón y Habsburgo-Lorena "out of the Law." This meant any Spanish citizen could arrest him if he entered Spain. He was stripped of all his titles and rights. All his property in Spain would be seized by the State. The prime minister, Manuel Azaña, said this vote was the "second proclamation of the Republic in Spain."

About a year later, on December 7, 1932, the former ministers of the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera were sentenced. They received sentences of twelve to eight years of confinement and twenty years of disqualification. However, none of them served their sentences because they were abroad. On May 2, 1934, the government pardoned them, allowing them to return to Spain.

See also

In Spanish: Reinado de Alfonso XIII de España para niños

In Spanish: Reinado de Alfonso XIII de España para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |