Warfare in early modern Scotland facts for kids

This article is about how people fought wars in Scotland from the early 1500s to the mid-1700s. This time is called the "early modern" period. It covers everything from how armies were put together to the weapons they used and how castles changed.

In the past, Scottish armies were formed in different ways. Sometimes, all men had to serve. Other times, lords had to provide soldiers because of old agreements. People also signed contracts called bonds or manrent to join. By 1513, these methods created a very strong army. But by the mid-1500s, it became harder to find enough soldiers.

Soldiers usually brought their own gear. This included axes and long pole weapons. Highland fighters often used bows and big two-handed swords. After a big battle called Flodden, heavy armor was not used as much. Highland lords still wore lighter chainmail. Regular Highlanders wore a plaid, which was a large piece of cloth. The king and queen started to help more with providing weapons. Long spears, called pikes, replaced shorter ones. Scots also began to use guns instead of bows. Heavy cavalry (soldiers on horses with lots of armor) were replaced by lighter horsemen. These often came from the Borders area.

King James IV even started a gun factory in 1511. Guns changed how castles were built. In the 1540s and 1550s, Scotland built new forts and added defenses to old castles. These helped protect the border.

Scotland also tried to create a royal navy in the 1400s. King James IV built a harbor at Newhaven and a shipyard at Airth. He got 38 ships, including the Great Michael, which was huge for its time. Scottish ships fought against pirates and helped the king explore the islands. They even sailed to Scandinavia. But after the Flodden battle, many ships were sold. Later, Scotland's navy often relied on private ships and hired merchant ships. These ships sometimes attacked enemy vessels, even during peace times. King James V built a new harbor at Burntisland in 1542. His ships were mostly used for trips to the Scottish islands and France.

When Scotland and England joined under one king in 1603 (the Union of Crowns), fighting between them stopped. But Scotland's ships now faced attacks because of England's wars. In 1626, Scotland bought three ships to protect its trade. Private ships with special permission also joined the fight. In 1627, the Scottish navy helped in a big battle in France. Scots also sailed to the West Indies and helped capture Quebec in 1629.

In the early 1600s, many Scots joined armies in other countries, especially during the Thirty Years' War. When Scotland and King Charles I started to fight (the Bishops' Wars), many experienced Scottish soldiers came home. Leaders like Alexander and David Leslie trained new soldiers. Scottish armies then fought in the Civil Wars in England and Ireland.

Scottish foot soldiers usually used pikes and muskets. But some also had bows or other pole weapons. Most cavalry had pistols and swords. Royalist armies, like those led by Montrose, also used pikes and muskets. But they often lacked heavy cannons and had few cavalry. During the Bishops' Wars, Scottish private ships captured English ships. Later, the Scots joined with the English Parliament. They set up two groups of patrol ships called the "Scotch Guard." These ships protected the coasts. However, the Scottish navy could not stop the English fleet led by Cromwell when he conquered Scotland in 1649–51. Scottish ships were then taken by the English fleet. During the English rule, more strong forts were built.

After the king returned to power (the Restoration), new army groups were formed. There were also attempts to create a national militia (citizen army). The army mostly put down rebellions by a group called the Covenanters. Pikemen became less important. After the socket bayonet was invented, which attached to a musket, pikes were no longer used. Older muskets were replaced by more reliable flintlock guns. Before the Glorious Revolution, Scotland's army had about 3,250 men. Scots soldiers then fought in King William II's wars in Europe. Scottish sailors were protected from being forced into the navy, but a certain number of men from coastal towns had to join the Royal Navy. Royal Navy ships also patrolled Scottish waters. Scottish privateers played a big part in the Second Anglo-Dutch War. In the 1690s, a group of five ships was created for the Darien Scheme, a plan to start a Scottish colony. A small navy of three warships was also built to protect local ships. After Scotland and England officially united in 1707 (the Act of Union), these ships joined the Royal Navy.

At the time of the Union, Scotland's army had seven groups of foot soldiers, two of horse soldiers, and one group of Horse Guards. They also had cannons in castles. As part of the British Army, Scottish regiments fought in many wars in Europe. The first official Highland regiment (a group of soldiers from the Highlands) was the Black Watch, formed in 1740. This was the start of Highlanders playing a big role in the British army. But the growth of Highland regiments was slowed down by the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion. Most Jacobite armies were made up of Highlanders, fighting in clan groups. Jacobite soldiers often started campaigns with poor weapons. But as the rebellions went on, they got more regular weapons.

Contents

Sixteenth Century Warfare

How Royal Armies Were Formed

In the later Middle Ages, Scottish armies were still mostly gathered based on old traditions. Men had to serve the king, or lords had to provide soldiers because of feudal agreements. Sometimes, soldiers were hired using money contracts called bonds or bands of manrent.

Common service meant that all men aged 16 to 60 could be called to fight. They would serve for up to 40 days a year. These soldiers had to pay for their own food and supplies. This made it hard for Scottish armies to fight long wars.

Feudalism came to Scotland in the 1100s. This meant knights held land in exchange for military service. They provided soldiers for 40 days, especially heavily armored cavalry. Bonds of manrent were like contracts to hire more professional soldiers, such as men-at-arms and archers. Scotland used these old systems longer than England did. In reality, these different ways of getting soldiers often mixed together. Important Scottish lords still brought groups of fighters from their own families.

In 1513, for the Flodden campaign, these systems worked well. They created a large and strong army. But in the mid-1500s, Scotland was divided by religion and politics. It became harder for leaders to find enough people to join the army.

Soldiers' Gear and Weapons

Soldiers had to show their equipment several times a year at events called wapenshaws. This was to make sure they had the right gear for war. People were expected to equip themselves based on their social standing. In 1513, gentlemen were told to wear plate armour. Regular soldiers were to wear padded jackets called jacks and helmets called sallets.

After the terrible defeat at Flodden, noblemen seemed to stop wearing heavy plate armor. Maybe it was too hard to use with the long pikes. By 1547, many noblemen looked almost the same as regular soldiers. Highland lords still wore lighter chainmail. Regular Highlanders wore the plaid and left their lower legs bare. Instead of a jack, they often wore a linen garment covered with wax or pitch.

A clan leader, like John Grant of Freuchie in 1596, could gather 500 men from his family and friends. These men could fight for King James VI. Of these, 40 had habergeons (chainmail shirts), two-handed swords, and helmets. Another 40 were armed "Highland style" with bows, helmets, swords, and small shields called targes.

Weapons included different kinds of axes and long pole weapons. These were spears, the Lochaber axe, Leith axe, and Jedburgh stave. Highland soldiers often brought bows, two-handed swords (claidheamh mór), and axes. The king and queen started to play a bigger role in providing equipment.

There were attempts to replace shorter polearms with longer pikes, about 15 to 18 feet long. This was to copy the success of armies in the Netherlands and Switzerland against horse soldiers. But it didn't really work until just before the Flodden campaign in the early 1500s. By the mid-1500s, the pike was the most important weapon for Scottish foot soldiers. Scottish tactics were like those of Swiss and German infantry. They focused on quickly attacking the enemy. This was important to counter the English, who had better long-range weapons.

Like most European countries, the Scots started to use guns instead of bows during this time. Handguns were used in small numbers in Scottish armies from the 1400s. Records show more and more mentions of handguns and arquebuses. A report from the Haddon Rig in 1542 suggests that half of the Scottish soldiers used long-range weapons, and half of those used arquebuses. Scottish commanders aimed to have equal numbers of long-range and close-combat soldiers. But this was not always possible in battles. France was the main source of firearms for Scotland. The French seemed to rearm the Scots a lot after the English invasions during the Rough Wooing.

The English had a much stronger cavalry than the Scots. This was especially true with their use of demi-lancers (heavily armed horsemen). The old feudal heavy cavalry had started to disappear from Scottish armies after the Bannockburn in 1314. This was because there weren't enough suitable horses. King James V brought in large horses from Denmark to try and improve Scottish horse breeding. In the mid-1500s, the Scots still didn't have enough heavy cavalry. Instead, they used many light horsemen, often from the Borders. These riders usually wore leather or chainmail jackets. They rode small horses and used light lances. As guns became available, they started to use many mounted arquebusiers (horsemen with guns).

Cannons and Castle Defenses

King James IV brought in experts from France, Germany, and the Netherlands. He set up a gun factory in 1511. Edinburgh Castle had a special building where visitors could see cannons being made. This created a very strong collection of cannons. It allowed him to send cannons to France and Ireland. He could also quickly capture Norham Castle in the Flodden campaign. However, his 18 heavy cannons needed 400 oxen to pull them. This slowed down the Scottish army. These cannons were not effective against the English guns, which had a longer range and smaller size, at the Battle of Flodden Field.

Gunpowder weapons completely changed how castles were built from the mid-1400s. Old castles were changed to use guns. They added "keyhole" gun ports, platforms for cannons, and stronger walls to resist cannon fire. Ravenscraig, built around 1460, was probably the first castle in Britain designed as a fort for cannons. It had "D-shaped" towers that could better resist cannon fire and hold cannons.

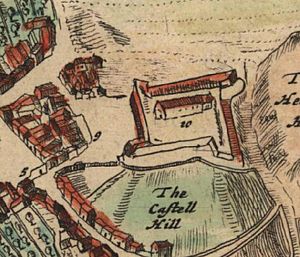

In the 1540s and 1550s, when France helped Scotland during the Rough Wooing wars, Scotland got a defended border. This included a series of earth forts and additions to existing castles. For example, single strong points called bastions were built at Edinburgh, Stirling, and Dunbar. The Scots' Dike was built on the western border. New forts with angled walls (called trace italienne) were built at Leith, Inchkeith, and Langholm. Work also started at Jedburgh, and plans were made for forts at Kelso. The most daring move was a fortified cannon park at Eyemouth. This was only 6 miles (10 km) from the English stronghold of Berwick.

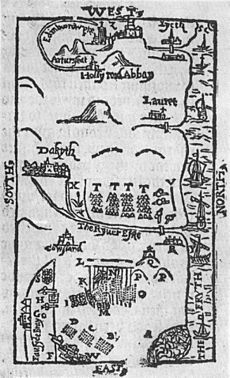

There were several attempts to create a royal navy in the 1400s. King James IV put a new focus on it. He founded a harbor at Newhaven in 1504. Two years later, he ordered a shipyard built at the Pools of Airth. New forts on Inchgarvie protected the upper parts of the Forth River. The king got 38 ships for the Royal Scottish Navy. These included the Margaret and the large Michael or Great Michael. The Great Michael was built at Newhaven and launched in 1511. It was 240 feet (73 meters) long, weighed 1,000 tons, and had 24 cannons. At that time, it was the largest ship in Europe.

Scottish ships had some success against privateers (private ships allowed to attack enemy ships). They went with the king on his trips to the islands. They also got involved in fights in Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea. In the Flodden campaign, the fleet had 16 large and 10 smaller ships. After attacking Carrickfergus in Ireland, it joined the French fleet. But it didn't have much impact on the war. After the disaster at Flodden, the Great Michael and maybe other ships were sold to the French. The king's ships are not mentioned in records after 1516. Scotland's navy then relied on privateer captains and hired merchant ships while James V was a child.

In the Italian War of 1521–26, England and Scotland were on opposite sides. The Scots had six men-of-war (warships) attacking English and Imperial ships. They blocked the Humber River in 1523. Although Robert Barton and other captains captured enemy ships, the naval campaign was not very organized or decisive.

King James V became an adult in 1524. He wasn't as interested in building a navy as his father. He relied on gifts from France, like the Salamander, or captured ships, like the English Mary Willoughby. Scotland's shipbuilding mostly stayed at the level of building small boats and repairing ships. It fell behind countries like the Netherlands, which were becoming leaders in shipbuilding.

Even though England and Scotland had truces, there were regular attacks on merchant ships in the 1530s. At least four of Scotland's six known warships were royal navy vessels. King James V built a new harbor at Burntisland in 1542. It was called 'Our Lady Port' or 'New Haven'. In 1544, it was described as having three blockhouses with guns and a pier for large ships.

The main use of naval power during his reign was a series of trips to the Scottish Isles and France. In 1536, the king sailed around the Isles. He started at Pittenween in Fife and landed at Whithorn in Galloway. Later that year, he sailed from Kirkcaldy with six ships, including the 600-ton Mary Willoughby. He arrived at Dieppe to meet his first wife, Madeleine of Valois. After his marriage, he sailed from Le Havre in the Mary Willoughby to Leith. He had four large Scottish ships and ten French ones with him. After Queen Madeleine died, John Barton, in the Salamander, went back to France in 1538. He picked up the new queen, Mary of Guise, with the Moriset and Mary Willoughby.

In 1538, King James V boarded the newly equipped Salamander at Leith. Accompanied by the Mary Willoughby, the Great Unicorn, the Little Unicorn, the Lion, and twelve other ships, he sailed to Kirkwall on Orkney. Then he went to Lewis in the West. He might have used the new maps from his first voyage, known as Alexander Lindsay's Rutter.

Scottish privateers and pirates attacked ships in the North Sea and off the French Atlantic coast. Scotland's Admiralty court decided if a captured ship was a legal prize. It also handled getting goods back. The court got a tenth of the value of a captured ship, so it was a good business for the admiral. The privateers Andrew and Robert Barton were still using their special permissions from 1506 against the Portuguese in 1561. The Bartons operated along the east coast of Britain from Leven and the Firth of Forth. Others used French Channel ports like Rouen and Dieppe, or the Atlantic port of Brest as their bases.

During the Rough Wooing in 1542, the Mary Willoughby, the Lion, and the Salamander (led by John Barton, Robert Barton's son) attacked merchants and fishermen near Whitby. They later trapped a London merchant ship called the Antony of Bruges in a small bay on the coast of Brittany. In 1544, Edinburgh was attacked and burned by an English naval force. The Salamander and the Scottish-built Unicorn were captured at Leith. The Scots still had two royal navy ships and many smaller private vessels. But they had to rely on privateers until a royal fleet was re-established in the 1620s.

When Emperor Charles V declared war on Scotland in 1544 (because of a series of international treaties), the Scots started a very profitable privateering campaign. It lasted six years. The money they gained probably made up for the losses in trade with the Netherlands. They also operated in the West Indies from the 1540s. They joined the French in capturing Burburuta in 1567. English and Scottish naval warfare and privateering broke out now and then in the 1550s. In 1559, English captain William Winter was sent north with 34 ships. He scattered and captured the Scottish and French fleets. This led to the French leaving Scotland. It also helped the Protestant Lords of the Congregation take power. Scottish and English interests then aligned, and the naval conflict calmed down.

Early Seventeenth Century Warfare

Royal and Private Fleets

After the Union of Crowns in 1603, fighting between Scotland and England stopped. But Scotland became involved in England's foreign policy. This meant Scottish ships were now open to attack. In the 1620s, Scotland found itself fighting a naval war as England's ally. First, it was against Spain, then against France. At the same time, Scotland was involved in undeclared conflicts in the North Sea during the Danish part of the Thirty Years' War.

In 1626, three ships were bought and equipped for at least £5,200. These were to guard against privateers from Spanish-controlled Dunkirk. Other ships were also armed. The acting High Admiral, John Gordon of Lochinvar, organized at least three groups of privateers with special permissions (called marque fleets). It was probably one of Lochinvar's fleets that helped the English Royal Navy protect Irish waters in 1626. In 1627, the Royal Scots Navy and privateers from towns took part in a major expedition to Biscay.

The Scots also returned to the West Indies. Lochinvar captured French ships and started a colony called Charles Island. In 1629, two groups of privateers, led by Lochinvar and William Lord Alexander, sailed to Canada. They helped in the campaign that captured Quebec from the French. Quebec was later given back after peace was made.

Covenanter Armies

In the early 1600s, many Scots joined foreign armies during the Thirty Years' War. About 20,000 to 30,000 Scots served in the Swedish army. There was a Scottish group in the Netherlands. Between 1626 and 1627, 5,000 to 6,000 Scots joined the Danish army. Another 11,000 went to France. Many also served in armies in Eastern Europe, including German states, Poland, and Russia.

As fighting between Scotland and King Charles I seemed more likely from 1637, a group called the Standing Committee of the Tables started acting as a war council. It appointed two lairds (landowners) in every parish. Their job was to list men suitable for military service, available weapons, and the names of Scots serving abroad so they could be called home. Three commissioners were appointed in each shire (county). Two stayed in Edinburgh, and one stayed in the local area. Local church groups (presbyteries) appointed commissioners to pass on instructions to the parishes.

Hundreds of Scottish soldiers who had been fighting abroad came home. These included experienced leaders like Alexander and David Leslie. These veterans were very important in training the new recruits from the parishes. Nobles could raise their own regiments, which were usually named after them. They could appoint company commanders. But the second-in-command (lieutenant colonel) and the main sergeant (sergeant major) of the regiment, and the lieutenant and sergeant of each company, had to be professional soldiers. The returning soldiers also brought knowledge of building forts. New forts with angled walls (trace italienne) were added at Leith, Burntisland, and Greenock. These would be very important during the siege of Edinburgh in 1650.

Leslie's appointment as field marshal prevented inexperienced nobles from fighting over leadership. His good reputation made it more likely for Scottish soldiers to join the Covenanter armies. He became a member of the Tables, which allowed him to influence decisions and send out orders. Even though it created a relatively large and well-organized army, it was put together quickly. It also lacked money and supplies. The Covenanter government had to collect money from parishes and relied on loans from Edinburgh merchants. This made it hard to keep a long campaign going. According to historian James Scott Wheeler, the first Covenanter army was "marginally trained, irregularly armed, poorly paid and badly supplied." But it was good enough for the job.

Between the two Bishops' Wars, the Covenanters kept one regiment of foot soldiers. Many of their officers, who had trained the local militias, were on half pay. The militias now had firearms bought from the Netherlands. The Tables were replaced by a committee of estates, which had wide powers. It kept the same system of commissioners. One in four able-bodied men could be called to fight when mobilization started again in 1640. The army was paid for by more loans and a new national tax called the "tenth" or "tenth penny." These systems would be the basis for the Covenanter armies that fought in Ireland. They also joined the First Civil War (1642–46) in England on the side of Parliament. Later, and less successfully, they fought on the king's side in the Second (1648–49) and Third Civil Wars (1649–51).

Scottish foot soldiers usually used a combination of pikes and muskets, which was common in Western Europe. Pikes were supposed to be 16 feet (4.9 meters) long. But they were often shortened by a foot or two to make them easier to handle. This had terrible results at the Battle of Benburb (1646). There, the Confederate Irish defeated the Scots because they had longer pikes. Musketeers mainly used matchlock muskets. Some had firelocks (probably saved for soldiers guarding supplies). A few troops had more accurate rifled guns. Experience from Europe showed that firepower was becoming more important than close combat. This was seen in the higher number of muskets compared to pikes, usually three muskets for every two pikes. Scottish armies might also have had individuals with bows, Lochaber axes, and halberds. Recruits who didn't have pikes or muskets were told to bring these weapons. Most cavalry probably had pistols and swords. But there is some evidence that they included lancers (soldiers with long spears).

Royalist armies, like those led by James Graham, Marquis of Montrose (1643–44) and in Glencairn's rising (1653–54), mostly had foot soldiers with pikes and muskets. Montrose's army also included Irish soldiers and Scottish recruits from Highland clans who were against the Clan Campbell. These were led by Alasdair Mac Colla. Glencairn's rising got some support from Lowland Scottish lords. At its peak, it had 3,500 foot soldiers and 1,500 cavalry. Montrose's forces had about the same number of foot soldiers. But they lacked heavy cannons for sieges and had only a small group of cavalry, about 300, provided by the Earls of Huntly.

During the Bishops' Wars, the king tried to block Scotland. This stopped trade and the movement of soldiers returning from Europe. The king planned attacks by sea from England on the east coast and from Ireland to the west. But these attacks never happened. Scottish privateers captured English ships. The Covenanters planned to equip Dutch ships with Scottish and Dutch crews to help in the naval war.

After the Covenanters allied with the English Parliament, they set up two patrol groups for the Atlantic and North Sea coasts. These were known as the "Scotch Guard." These patrols guarded against Royalist attempts to move men, money, and weapons. They also protected Scottish shipping, especially from ships based in Wexford and Dunkirk. These patrols mainly used small English warships. They were controlled by the Commissioners of the Navy in London. But they always relied heavily on Scottish officers and money. After 1646, the West Coast group became much more a Scottish force. The Scottish navy could not stop the English fleet that came with Cromwell's army. Cromwell conquered Scotland in 1649–51. The Scottish ships and crews were then divided among the English fleet.

Fortifications and Defenses

During the English occupation of Scotland under the Commonwealth, new forts were built. These were in the style of the trace italienne, which had angled walls. Examples were at Ayr, Inverness, and Leith. Twenty smaller forts were built as far away as Orkney and Stornoway. Control of the Highlands was secured by strong points at Inverlocky and Inverness.

These forts cost a huge amount of money and manpower. The fort at Inverness, started in 1652, used stone shipped from as far away as Aberdeen. It had cost £50,000 by 1655, even though it was still unfinished. Inverlochy had 1,000 soldiers. From 1654, it became the center for a new administrative region called Lochaber. This area included three of the most remote and lawless shires.

Later Seventeenth Century Warfare

The Restoration Army

When the king returned to power (the Restoration), the Privy Council (a group of advisors) created an unknown number of foot soldier regiments and a few groups of horse soldiers. The forts built by the Commonwealth were abandoned. But soldiers were placed in Edinburgh, Stirling, Dumbarton, and Blackness castles. There were attempts to create a national militia (citizen army) like the English one.

The standing army was mainly used to put down rebellions by the Covenanters. It also fought a guerrilla war (small, surprise attacks) by the Cameronians in the East. Groups included a regiment of foot guards, later known as the Scots Guards. Another group, Le Regiment of Douglas, had been formed and serving in France since 1633. It returned and eventually became the Royal Regiment of Foot.

Pikemen became less important in the late 1600s. After the socket bayonet was invented, which attached to a musket, pikes disappeared completely by 1702. Older matchlock muskets were replaced by the more reliable flintlock muskets. Three groups of Scots Dragoons (horse soldiers who could also fight on foot) were raised in 1678. Another three were added to create The Royal Regiment of Scots Dragoons in 1681.

Before the Glorious Revolution, the standing army in Scotland had about 3,000 men in different regiments. Another 268 experienced soldiers were in the main garrison towns. This cost about £80,000 a year. After the Glorious Revolution, the Scots were drawn into King William II's wars in Europe. This started with the Nine Years' War in Flanders (1689–97).

Under King Charles II, Scottish sailors were protected from being forced into English warships. However, a fixed number of men from coastal towns had to join the Royal Navy during the second half of the 1600s. Royal Navy ships now patrolled Scottish waters even in peacetime. For example, the small warship HMS Kingfisher attacked Carrick Castle during the Earl of Argyll's rebellion in 1685.

Scotland fought against the Dutch and their allies in the Second (1665–67) and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars (1672–74) as an independent kingdom. Scottish captains, at least 80 and perhaps 120, got special permissions (letters of marque). Privateers played a major part in the naval fighting during these wars.

By 1697, the English Royal Navy had 323 warships. Scotland still relied on merchant ships and privateers. In the 1690s, two separate plans for larger naval forces were started. As usual, private merchants played a bigger part than the government. The first was the Darien Scheme to start a Scottish colony in Spanish-controlled America. This was done by the Company of Scotland. They created a fleet of five ships, including the Caledonia and the St. Andrew. These were built or rented in Holland and Hamburg. The fleet sailed to the Isthmus of Darien in 1698. But the plan failed, and only one ship returned to Scotland.

At the same time, it was decided to create a professional navy to protect trade in Scottish waters during the Nine Years' War. Three warships were bought from English shipbuilders in 1696. These were the Royal William, a 32-gun ship, and two smaller ships, the Royal Mary and the Dumbarton Castle, each with 24 guns. These were usually called frigates. After the Act of Union in 1707, the Scottish Navy joined with England's. The three ships of the small Royal Scottish Navy were transferred to the Royal Navy.

Early Eighteenth Century Warfare

The Royal Army

By the time of the Act of Union, Scotland had a standing army of seven groups of foot soldiers, two groups of horse soldiers, and one group of Horse Guards. They also had cannons in the garrison castles of Edinburgh, Dumbarton, and Stirling. Their role was so important that the Scottish Parliament made Queen Anne agree to the controversial 1704 Act of Security. They threatened to pull Scottish forces out of the allied armies if she didn't.

The new British Army, created by the Act of Union in 1707, included existing Scottish regiments. These were groups like the Scots Guards, The Royal Scots 1st of Foot, King's Own Scottish Borderers 25th of Foot, The Cameronians 26th of Foot, Scots Greys, and the Royal Scots Fusiliers 21st of Foot. The new armed forces were controlled by the War Office and Admiralty from London.

During this time, Scottish soldiers and sailors were very important in helping the British Empire grow. They also got involved in international conflicts. These included the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–13), the Quadruple Alliance (1718–20), wars with Spain (1727–29) and (1738–48), and the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48).

The first official Highland regiment to be raised for the British army was the Black Watch. This was the 43rd (later 42nd) regiment, formed in 1740. It marked the beginning of Highlanders playing a major role in the British military. But the growth of Highland regiments was delayed by the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion. It didn't really begin until the late 1750s.

Jacobite Armies

Most Jacobite armies were made up of Highlanders. They served in clan regiments. They made up 70 percent of the forces in the 1715 rebellion and over 90 percent in 1745. Most were forced to join by their clan chiefs, landlords, or feudal superiors. Soldiers leaving without permission was a big problem during campaigns. The Jacobites also lacked trained officers.

A typical clan regiment had a small number of gentlemen (called tacksmen) who shared the clan name. These clan gentlemen formed the front ranks of the unit. They were more heavily armed than their poorer tenants, who made up most of the regiment. Because they fought in the front ranks, the gentlemen suffered more casualties than the common clansmen.

The Jacobites often started campaigns with poor weapons. In the 1745 rising, at the Battle of Prestonpans, some soldiers only had swords, Lochaber axes, pitchforks, and scythes. But as the campaigns went on, their weapons became more conventional. Only officers and gentlemen had a broadsword, a targe (small shield), and a pistol. After the Battle of Culloden in 1746, the Hanoverian commander, the Duke of Cumberland, reported that 2,320 muskets were found on the battlefield, but only 190 broadswords.

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |