History of Montenegro facts for kids

The early history of Montenegro starts with the Illyrians, who lived in this area. Later, the Roman Republic took control of the region, making it part of their provinces like Illyricum.

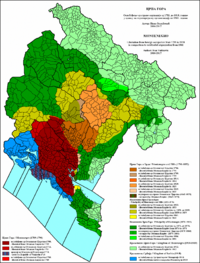

In the Early Middle Ages, many Slavic people moved into the area. By the 9th century, there were three main Slavic states in what is now Montenegro: Duklja in the south, Travunia in the west, and Rascia in the north. In 1042, a leader named Stefan Vojislav led a rebellion that made Duklja independent. His family, the Vojislavljević dynasty, ruled for a long time. Duklja became very strong under Vojislav's son, Mihailo, and his grandson Bodin. By the 13th century, people started calling the area Zeta instead of Duklja.

Later, in the late 1300s, southern Montenegro (Zeta) was ruled by the Balšić noble family, and then the Crnojević noble family. By the 15th century, Zeta was often called Crna Gora, which means "Black Mountain" in Venetian.

From 1496 to 1878, large parts of Montenegro were controlled by the Ottoman Empire. Some coastal areas were controlled by the Republic of Venice. For a long time, from 1516 to 1852, the country was led by religious leaders called prince-bishops (vladikas). The House of Petrović-Njegoš family then ruled until 1918. After that, Montenegro became part of Yugoslavia. In 2006, after a special vote, Montenegro became an independent country again on June 3.

Contents

Early History of Montenegro

Before the Slavs arrived in the Balkans around the 6th century AD, the area of Montenegro was mostly home to the Illyrians.

During the Bronze Age, a group called the Illirii lived near Skadar lake, close to the border of Albania and Montenegro. They were neighbors with Greek tribes to the south. Along the Adriatic coast, many different people settled, including colonists, traders, and those looking for new lands. Important Greek colonies were set up in the 6th and 7th centuries BC. Celts also settled there in the 4th century BC.

In the 3rd century BC, an Illyrian kingdom grew, with its capital at Scutari. The Romans fought against local pirates and eventually conquered the Illyrian kingdom in the 2nd century BC. They added it to their province called Illyricum.

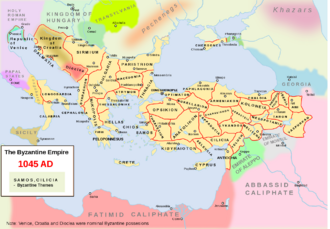

The Roman Empire later split into Western and Eastern (Byzantine) parts. This division, and the split between the Latin (Catholic) and Greek churches, created a border through modern Montenegro. This showed that the region was always a meeting point between different cultures and powers. As Roman power weakened, this part of the Dalmatian coast was attacked by groups like the Goths in the late 5th century and the Avars in the 6th century.

Soon, the Slavs arrived and settled widely in Dalmatia by the mid-7th century. Because the land was very rugged and didn't have much wealth like minerals, the area that is now Montenegro became a safe place for smaller groups of earlier settlers. This included some tribes who had not been fully influenced by Roman culture.

Middle Ages in Montenegro

In the late 6th century, Slavs moved from the Bay of Kotor to the Bojana River and around Skadar Lake. They formed a state called the Principality of Doclea. With the help of Cyril and Methodius, the people became Christian. By the 9th century, the Slavic tribes had organized into a semi-independent dukedom of Duklja.

After a period under Bulgarian rule, the people of Doclea faced new challenges. In the 10th century, Prince Časlav Klonimirović of the Serbian Vlastimirović dynasty extended his power over Doclea. After the Serbian Realm fell in 960, the Byzantines took control of Doclea again until the 11th century. The local ruler, Jovan Vladimir Dukljanski, tried to keep his land independent.

Stefan Vojislav led an uprising against Byzantine rule. In 1042, he won a big victory against the Byzantine army in Tudjemili (Bar), ending their influence over Doclea. In the Great Schism of 1054, Doclea sided with the Catholic Church. Bar became a Bishopric in 1067. In 1077, Pope Gregory VII recognized Duklja as an independent state. He also recognized its King Mihailo (of the Vojislavljević dynasty) as the King of Duklja. Mihailo later sent his troops, led by his son Bodin, to help a Slavic uprising in Macedonia in 1072. In 1082, the Bishopric of Bar was made an Archbishopric.

The Vojislavljević kings expanded their control over other Slavic lands, including Zahumlje, Bosnia, and Rascia. However, the power of Doclea declined, and by the 12th century, they generally came under the rule of the Grand Princes of Rascia. Stefan Nemanja was born in 1117 in Ribnica (today Podgorica). In 1168, as the Serbian Grand Zhupan, Stefan Nemanja took Doclea. Records from the 14th century mention different groups living there, including Albanians, Vlahs, Latins (Catholic citizens), and Serbs.

Zeta within the Nemanjić State (1186–1360)

The region of Duklja, also known as Zeta, was ruled by the Nemanjić family from about 1186 to 1360. During this time, Zeta was managed by members of the Serbian royal family as a special territory.

Zeta under the Balšići (1360–1421)

The Principality of Zeta was ruled by the house of Balšić from about 1356 until 1421.

Zeta under the Crnojevići (1451–1496)

The Principality of Zeta was ruled by the Crnojević Dynasty from about 1451 until 1496. It is believed that the name Crna Gora (Montenegro) came about during their rule. The Crnojevići were pushed out of Zeta by the Ottomans. They had to move above the Gulf of Kotor where they built a monastery and a royal court in Cetinje. Cetinje later became the capital of Montenegro. Eventually, they fled to Venice. In 1496, the Ottomans conquered Zeta and made it part of their new Sanjak of Montenegro, ending its time as a principality.

The Venetian Coastal Montenegro

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, the Romanized Illyrians living on the coast of Dalmatia survived attacks by groups like the Avars in the 6th century. They were only slightly influenced by the Slavs in the 7th and 8th centuries. In the last centuries of the first millennium, these Romanized Illyrians started to develop their own language, called Dalmatian language, in their small coastal villages that grew with sea trade.

Venice began to take control of southern Dalmatia around the 10th century. They quickly blended the Dalmatian language with the Venetian language. By the 14th century, the Republic of Venice had continuous control around the Bay of Kotor (Cattaro).

Early Modern Period

The Republic of Venice controlled the coasts of modern-day Montenegro from 1420 to 1797. During these four centuries, the area around Cattaro (Kotor) became part of Venetian Albania.

Struggle for Independence (1496–1878)

A part of modern-day Montenegro, called Sandžak, was directly controlled by the Ottoman Empire from 1498 to 1912. The westernmost part of coastal Montenegro was under Venetian control. The rest of Montenegro became mostly self-governing from 1516. In that year, Vladika Vavila was chosen as the ruler by the Montenegrin clans. He was also recognized by the Ottoman Empire. This made Montenegro a religious state, not a secular one.

Only small towns like Cetinje and Njegusi were controlled by the Ottomans. However, the mountains and rural areas were self-governing and controlled by several Montenegrin clans. These clans were warrior societies, but they paid a special tax to the Ottoman Empire.

In 1514, the Ottoman territory of Montenegro was declared a separate Sanjak of Montenegro by Sultan Beyazid II. The first governor, or Sanjak-beg, was Ivan Crnojević's son, Staniša (Skenderbeg Crnojević). He converted to Islam and ruled until 1528. Even though Skenderbeg was known for his cruelty, the Ottomans did not have strong control over Montenegro. Vladika Vavil was chosen in 1516 as the Montenegrin prince-bishop by the Montenegrin people and the patriarch of Belgrade.

Elective Vladikas (1516–1696)

For 180 years, the Vladikas were chosen by the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć and the clans. This system changed to a hereditary one in 1696. During most of this time, the Montenegrin people were constantly fighting for their freedom within the Ottoman Empire.

Another person from the Crnojević noble family who had converted to Islam tried to take over Montenegro, just like Staniša had done earlier. But the civil governor, Vukotić, pushed back the Turkish attack. The Montenegrins, feeling strong after this victory, surrounded Jajce in modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Turks were too busy fighting the Hungarian war to get revenge. The next Ottoman invasion of Montenegro happened in 1570.

Historians don't say much about the Haraç (a tax in the Ottoman Empire) that the invaders supposedly collected from the people in the free mountains. The proud Montenegrin clans refused to pay this tax any longer. This led to an invasion by the Pasha during the time of the Hadjuk Bishop Rufim. The Turks were driven back with heavy losses in the Battle of Lješkopolje in 1604. About 1500 Montenegrin warriors attacked the Turkish camp of 10,000 Ottoman soldiers at night and won.

In 1613, Arslan Pasha gathered an army of over 40,000 men to attack part of Old Montenegro. This Ottoman army was twice as large as the entire population of Old Montenegro. On September 10, the Montenegrins met the Turkish army in the same place where Skenderbeg Crnojević had been defeated almost a century before. The Montenegrins, even with help from some neighboring tribes, had only 4000 fighters and were greatly outnumbered. However, the Montenegrins managed to defeat the Turks. Arslan Pasha was wounded, and the heads of his second-in-command and a hundred other Turkish officers were displayed on the walls of Cetinje. The Ottoman troops retreated in chaos; many drowned in the waters of the Morača River. Others were killed by Montenegrin fighters chasing them.

A writer named Mariano Bolizza, a Venetian nobleman living in Kotor in the early 17th century, described Montenegro at this time. He explained why they were so successful in war, even against much larger forces. In 1614, he published a description of Cetinje. At that time, the total male population of Cetinje available for war was 8,027 people, spread across ninety-three villages.

Life in the country was naturally unsettled during this period. War was the main activity for the people out of necessity, and peaceful arts suffered. The printing-press, which had been active a century earlier, no longer existed. The Prince-Bishop had weak control over the five nahije (districts) that made up the principality. The capital itself had only a few houses. Still, there was a system of local government. Each nahija was divided into tribes, each led by a chief (knez), who acted as a judge for disputes among the tribesmen.

Modern History of Montenegro

Petar Petrović Njegoš, an important vladika, ruled in the first half of the 19th century. In 1851, Danilo Petrović Njegoš became vladika. But in 1852, he got married and gave up his religious role. He took the title of knjaz (Prince) Danilo I, and changed his land into a secular principality.

After Danilo was assassinated in Kotor in 1860, the Montenegrins declared Nicholas I as his successor on August 14 of that year. In 1861–1862, Nicholas fought an unsuccessful war against the Ottoman Empire.

After the Herzegovinian Uprising, which he partly encouraged, he again declared war on Turkey. Serbia joined Montenegro, but was defeated by Turkish forces that same year. Russia then joined in and decisively defeated the Turks in 1877–78. The Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878) was very good for Montenegro, as well as Russia, Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria. However, some of these gains were reduced by the Treaty of Berlin (1878). In the end, Montenegro was recognized internationally as an independent state. Its territory effectively doubled, gaining about 1900 square miles (4900 km²). The port of Bar and all Montenegrin waters were closed to warships of all nations. The management of maritime and health police on the coast was given to Austria.

Under Nicholas I, the country also received its first constitution in 1905 and became a kingdom in 1910.

In the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), Montenegro gained more territory by sharing the Sanjak region with Serbia. However, the captured city of Skadar had to be given to the new state of Albania. This was insisted upon by the Great Powers, even though Montenegrins had lost 10,000 lives to conquer the town from Ottoman-Albanian forces.

World War I

Montenegro suffered greatly in World War I. Soon after Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia (July 28, 1914), Montenegro quickly declared war on the Central Powers – first on Austria-Hungary – on August 6, 1914. This was despite Austrian offers to give Shkoder to Montenegro if it stayed neutral. To coordinate the fight, Serbian General Božidar Janković was made head of the High Command for both Serbian and Montenegrin armies. Montenegro received 30 artillery pieces and financial help from Serbia. France sent a small group of 200 soldiers to Cetinje at the start of the war, as well as two radio stations. Until 1915, France supplied Montenegro with war materials and food through the port of Bar, which was blocked by Austrian warships. In 1915, Italy took over this role, but supplies were irregular due to attacks by Albanian groups. A lack of vital materials eventually led Montenegro to surrender.

Austria-Hungary sent a separate army to invade Montenegro in January 1916. This was to prevent the Serbian and Montenegrin armies from joining forces. However, this force was pushed back. From the strong forts on Mount Lovćen, the Montenegrins bombed Kotor, which was held by the enemy. The Austro-Hungarian army managed to capture Pljevlja, while the Montenegrins took Budva, which was then under Austrian control. The Serbian victory at the Battle of Cer (August 15–24, 1914) moved enemy forces away from Sandžak, and Pljevlja returned to Montenegrin hands. On August 10, 1914, the Montenegrin infantry strongly attacked the Austrian garrisons, but they couldn't hold their initial gains. They successfully resisted the Austrians in the second invasion of Serbia (September 1914) and almost took Sarajevo. However, with the start of the third Austro-Hungarian invasion, the Montenegrin army had to retreat against much larger numbers. Austro-Hungarian, Bulgarian, and German armies finally took over Serbia (December 1915).

However, the Serbian army survived and, led by King Peter I of Serbia, began retreating across Albania. To support the Serbian retreat, the Montenegrin army, led by Janko Vukotić, fought in the Battle of Mojkovac (January 6–7, 1916). Montenegro also faced a large invasion in January 1916 and remained under the control of the Central Powers for the rest of the war. The Austrian officer Viktor Weber Edler von Webenau was the military governor of Montenegro from 1916 to 1917, followed by Heinrich Clam-Martinic.

King Nicholas fled to Italy in January 1916 and then to France. The government moved its operations to Bordeaux. Eventually, the Allies freed Montenegro from the Austrians. A new assembly in Podgorica, called the National Assembly of Podgorica, accused the King of trying to make a separate peace with the enemy. They removed him from power, banned his return, and decided that Montenegro should join the Kingdom of Serbia on December 1, 1918. Some former Montenegrin soldiers who were still loyal to the King started a rebellion against this merger, known as the Christmas Uprising (January 7, 1919).

Yugoslavia

Between the two World Wars, Nikola's grandson, King Alexander I, was a powerful figure in the Yugoslav government. In 1922, Montenegro became part of the Zeta area and later the Zeta Banate. The main city of this region became the former Montenegrin capital, Cetinje. During this time, Montenegrin people were still divided between the "Greens" and "Whites" political groups.

The main political parties in Montenegro included the Democratic Party, People's Radical Party, Communist Party of Yugoslavia, Alliance of Agrarians, Montenegrin Federalist Party, and the Yugoslav Republican Party. During this period, two big problems in Montenegro were the loss of its independence and a difficult economic situation. All parties except the Federalists agreed on the first issue, preferring a strong central government. The economic situation was more complex, but all parties agreed it was not good and the government wasn't doing enough to help. Montenegro was badly damaged by the war but never received the payments it was owed as an Ally. Most people lived in rural areas, but city dwellers had a better standard of living. There was little infrastructure, and industry was made up of only a few companies.

World War II and the Puppet "Kingdom of Montenegro"

During World War II, Italy, led by Benito Mussolini, occupied Montenegro in 1941. They added the area of Kotor (Cattaro) to the Kingdom of Italy. The Queen of Italy, Elena of Montenegro, was the daughter of the former King of Montenegro and was born in Cetinje.

The English historian Denis Mack Smith wrote that the Queen of Italy convinced her husband, King Victor Emmanuel III, to push Mussolini to create an independent Montenegro. This was against the wishes of fascist Croats and Albanians who wanted to expand their own countries into Montenegrin areas. Her nephew, Prince Michael of Montenegro, never accepted the offer to become king. He remained loyal to his nephew, King Peter II of Yugoslavia.

A puppet state called the Kingdom of Montenegro was set up under fascist control. Krsto Zrnov Popović returned from his exile in Rome in 1941 to try and lead the Zelenaši ("Green" party), who wanted the Montenegrin monarchy to be restored. This group was called the Lovćen Brigade. Montenegro was badly affected by a terrible guerrilla war, especially after Nazi Germany replaced the defeated Italians in September 1943.

During World War II, like in many parts of Yugoslavia, Montenegro experienced a kind of civil war. Besides the Montenegrin Greens, the two main groups were the Chetnik Yugoslav army and the Yugoslav Partisans. The Chetniks were loyal to the government in exile and mostly consisted of Montenegrins who saw themselves as Serbs. The Partisans wanted to create a Socialist Yugoslavia after the war. Both groups had some similar goals, especially wanting a united Yugoslavia and resisting the Axis powers. So, in 1941, they joined forces and started the 13th July uprising. This was the first organized uprising in occupied Europe. It happened just two months after Yugoslavia surrendered and freed most of Montenegrin territory. However, the rebels could not take control of major towns. After failing to free Pljevlja and Kolasin, the Italians, with German help, recaptured all the rebel territory.

At the leadership level, disagreements about how the state should be run (a central monarchy versus a federal socialist republic) eventually caused the two sides to split. They then became enemies. Both groups constantly tried to gain support from the people. The Chetniks lost support among the population, as did other Chetnik groups in Yugoslavia. Their idea of a unified Serbia within Yugoslavia made it hard to get support from people who saw Montenegro as its own nation. These factors, plus the fact that some Chetniks were talking with the Axis, led to the Chetnik Yugoslav army losing support from the Allies in 1943. In the same year, Italy, which had been in charge of the occupied zone, surrendered and was replaced by Germany. The fighting continued.

Podgorica was freed by the socialist Partisans on December 19, 1944, and the war of liberation was won. Josip Broz Tito recognized Montenegro's big contribution to the war against the Axis powers by making it one of the six republics of Yugoslavia.

Montenegro within Socialist Yugoslavia

From 1945 to 1992, Montenegro was one of the republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It was the smallest republic and had the fewest people. Montenegro became economically stronger than ever. It received help from federal funds because it was considered an under-developed Republic, and it also became a popular place for tourists. The years after the war were difficult and involved political changes. Krsto Zrnov Popović, the leader of the Greens, was killed in 1947. Ten years later, in 1957, the last Montenegrin Chetnik, Vladimir Šipčić, was also killed. During this time, Montenegrin Communists like Veljko Vlahović and Svetozar Vukmanović-Tempo held important positions in the Yugoslav federal government.

In 1948, Yugoslavia faced the Tito–Stalin split, a time of high tension between Yugoslavia and the USSR. This was caused by disagreements about each country's influence on its neighbors. Political unrest began within both the communist party and the nation. Communists who supported the Soviet Union faced punishment and imprisonment in various prisons, notably Goli Otok. Many Montenegrins, because of their traditional loyalty to Russia, sided with the Soviet Union. This political split led to the downfall of many important communist leaders. Many people imprisoned during this time were innocent, which the Yugoslav government later admitted. In 1954, a well-known Montenegrin politician, Milovan Đilas, was removed from the communist party for criticizing party leaders.

Through the late 1940s and all of the 1950s, the country's infrastructure was rebuilt thanks to federal money. Montenegro's historic capital, Cetinje, was replaced by Podgorica. Podgorica had become the biggest city in the Republic between the wars, even though it was mostly in ruins from heavy bombing in World War II. Podgorica had a better geographical location within Montenegro. In 1947, the capital of the Republic was moved to the city, which was then named Titograd in honor of Marshal Tito. Cetinje received the title of 'hero city' within Yugoslavia. Youth work actions built a railway between the two biggest cities, Titograd and Nikšić. They also built an embankment over Skadar lake connecting the capital with the major port of Bar. The port of Bar was also rebuilt after being damaged during the German retreat in 1944. Other ports that were improved included Kotor, Risan, and Tivat. In 1947, Jugopetrol Kotor was founded. Montenegro's industrial growth was shown by the founding of the electronic company Obod in Cetinje, a steel mill and Trebjesa brewery in Nikšić, and the Podgorica Aluminium Plant in 1969.

Breakup of Yugoslavia and the Yugoslav Wars

The breakup of communist Yugoslavia (1991–1992) and the start of a multi-party political system found Montenegro with young leaders who had come to power only a few years earlier.

Three men effectively led the republic: Milo Đukanović, Momir Bulatović, and Svetozar Marović. They all rose to power during a political shift within the Yugoslav Communist party. All three seemed like devoted communists at first, but they were also smart enough to understand the dangers of sticking to old ways in changing times. So, when the old Yugoslavia ended and the multi-party system began, they quickly changed the Montenegrin branch of the old Communist party. They renamed it the Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro (DPS).

Having all the resources and members of the old Communist party gave the DPS a big advantage over new parties. This allowed them to win the first multi-party elections in December 1990. The party has ruled Montenegro ever since, either alone or as a main part of different ruling groups.

During the early to mid-1990s, Montenegro's leaders supported the war efforts of Slobodan Milošević. Montenegrin reserve soldiers fought on the Dubrovnik front line in Croatia.

In April 1992, after a vote, Montenegro decided to join Serbia in forming the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY). This officially ended the Second Yugoslavia.

During the 1991–1995 Bosnian War and Croatian War, Montenegro's police and military forces were involved in actions in Dubrovnik, Croatia, and Bosnian towns alongside Serbian troops. These actions aimed to gain more territory.

In May 1992, the United Nations placed an embargo on FRY, which affected many parts of life in the country.

Because of its good location (access to the Adriatic Sea and a water link to Albania across Lake Skadar), Montenegro became a center for certain activities. All of Montenegro's industrial production had stopped. The main economic activity became the movement of goods that were in short supply, like petrol and cigarettes, which became very expensive. This became a common practice for years. The Montenegrin government either ignored these activities or sometimes took an active part in them.

Recent History (1996–Present)

In 1997, there was a strong disagreement over the presidential election results. It ended with Milo Đukanović winning against Momir Bulatović in a second round. There were some issues with the voting, but the results were allowed to stand. Former close friends became strong rivals, leading to a tense atmosphere in Montenegro in late 1997. This also split the Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro. Bulatović and his supporters left to form the Socialist People's Party of Montenegro (SNP), staying loyal to Milošević. Đukanović, however, started to distance himself from Serbia. This distance from Milošević's policies helped spare Montenegro from the heavy bombing that Serbia experienced in spring 1999 during the NATO air-campaign.

Đukanović clearly won this political struggle and remained in power. Bulatović, on the other hand, never held office in Montenegro again after 1997 and eventually left politics in 2001.

During the Kosovo War, many ethnic Albanians sought safety in Montenegro.

During the war, Montenegro was bombed as part of NATO operations against Yugoslavia, though not as heavily as Serbia. The targets were mostly military sites like Golubovci Airbase.

In 2003, after years of discussion and outside help, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia changed its name to "Serbia and Montenegro" and became a loose union. This union had a shared parliament and army. For three years (until 2006), neither Serbia nor Montenegro held a vote on breaking up the union. However, a vote was announced in Montenegro to decide the republic's future. The votes in the 2006 independence referendum resulted in 55.5% for independence, just above the 55% limit set by the EU. Montenegro declared independence on June 3, 2006.

Independent Montenegro

On June 28, 2006, Montenegro joined the United Nations as its 192nd member state.

For October 16, 2016, the day of the parliamentary election, a plan to overthrow the government of Milo Đukanović had been prepared, according to the Montenegrin Special Prosecutor. Fourteen people, including two Russian citizens and two Montenegrin opposition leaders, were accused of being involved in the plan.

In June 2017, Montenegro officially became a member of NATO. This decision was not supported by about half of the country's population and led to promises of strong reactions from Russia's government.

In April 2018, Đukanović, the leader of the ruling Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), won Montenegro’s presidential election. This experienced politician had served as Prime Minister six times and as President once before. He had been a dominant figure in Montenegrin politics since 1991.

In September 2020, Đukanović's pro-Western Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS) narrowly lost the parliamentary election after leading the country for 30 years. The opposition, For the Future of Montenegro (ZBCG) group, was mostly made up of Serb nationalist parties. A new government, which supported Serbia, was formed by Prime Minister Zdravko Krivokapić. However, Prime Minister Krivokapic's government was removed by a no-confidence vote after only 14 months. In April 2022, a new minority government was formed. It included moderate parties that are both pro-European and pro-Serb. The new government was led by Prime Minister Dritan Abazovic.

In March 2023, Jakov Milatović, a pro-Western candidate from the Europe Now movement, won the presidential election against the current president, Milo Đukanović. On May 20, 2023, Milatović became the President of Montenegro. In June 2023, the Europe Now movement won a quick parliamentary election. On October 31, 2023, Milojko Spajić of the Europe Now Movement became Montenegro's new prime minister, leading a group of both pro-European and pro-Serb parties.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Montenegro para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Montenegro para niños

- Demographic history of Montenegro

- Military history of Montenegro

- Tribes of Montenegro

Images for kids