History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1764–1795) facts for kids

The History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1764–1795) covers the last years of this large European country. During this time, the Commonwealth tried to make big changes to improve itself. However, its powerful neighbors divided its land in three parts, known as the Partitions of Poland. This period happened during the rule of the last king, Stanisław August Poniatowski.

In the late 1700s, the Commonwealth worked hard on important internal reforms. But these changes made its neighbors angry, leading to military actions against it. The economy got better, and the population grew a lot. Warsaw became the main trade city, taking over from Gdańsk. City people became more important and richer. The last years of the Commonwealth were full of reforms in education, thinking, arts, and sciences. The political system also started to change.

In 1764, Stanisław August Poniatowski was chosen as king. He was a smart and cultured nobleman. Empress Catherine II of Russia picked him, expecting him to obey her. The King wanted to make reforms to save his country. But he also felt he had to stay loyal to his Russian supporters.

The Bar Confederation of 1768 was a rebellion by Polish nobles (called szlachta). They fought against Russia and the Polish king. They wanted to keep Poland independent and protect their traditional rights. This rebellion was put down. In 1772, the First Partition happened. Russia, Prussia, and Austria took parts of the Commonwealth's land. The "Partition Sejm" (parliament) was forced to agree to this. In 1773, the Sejm created the Commission of National Education. This was a new government group for education, one of the first in Europe.

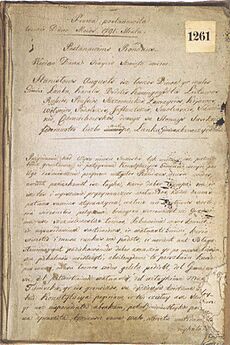

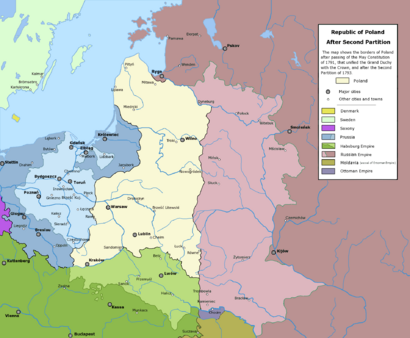

The Great Sejm, also called the Four-Year Sejm, started in 1788. Its biggest achievement was creating the Constitution of May 3, 1791. This was the first modern constitution in Europe. It was a moderate reform document. But some conservative nobles and Catherine II didn't like it. They feared a strong Commonwealth. The nobles formed the Targowica Confederation and asked the Empress for help. In May 1792, the Russian army entered the Commonwealth. The war ended when King Stanisław August Poniatowski joined the Targowica Confederation. He believed resistance was useless. The Confederation took control. But in 1793, Russia and Prussia arranged the Second Partition. This left the country much smaller and almost unable to exist on its own.

After these events, reformers wanted to start a national uprising. Tadeusz Kościuszko was chosen as the leader. He was a popular general. On March 24, 1794, in Kraków, he declared a national uprising. Kościuszko freed many peasants and let them join his army. City people also strongly supported the uprising. But it couldn't get enough foreign help. Russian and Prussian forces crushed it, capturing Warsaw in November. The third and final partition happened in 1795. All three powers took more land. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth officially ended.

Contents

Economy and Business Changes

New Business Ideas and Farming

Starting in the mid-1700s, the Commonwealth's economy began to change. It slowly moved towards a capitalist system. Countries in Western Europe were already more advanced. Their ideas from the Enlightenment helped Poland. Factories grew, populations increased, and wars were frequent in the West. This meant more demand for farm and forest products from the East. From the 1760s, prices for these goods went up. Poland's grain exports reached high levels again.

The local market also improved. More people lived in towns, and fewer worked on farms. Farmers could now invest more in their work. However, the Commonwealth started from a very low point in the early 1700s. Its growth was slower than countries like Great Britain or France. This economic weakness was a reason for its political and military problems.

Changes in farming were slow because people resisted new ideas. Growing potatoes became more common, especially in western areas. But overall, grain production wasn't as good as it had been during the Renaissance. Thinkers of the Enlightenment wanted to change how farms were run. They especially focused on serfdom, where peasants were tied to the land. Landowners found that forced labor by serfs wasn't very productive. They started to use hired workers or rent out land to peasants.

Hired farm workers were in demand, and wages were offered. Renting land gave peasants more freedom if the fees were fair. These new ways of farming were used in only a few places, mostly in the western parts of the Commonwealth. But forced labor by serfs remained the main way of farming in most of Poland and Lithuania.

Factories and Trade

The Commonwealth's wealth mostly came from farming. But changes in cities and factories were very important in the late 1700s. At first, factories and crafts were not well developed compared to Prussia, Austria, and Russia. The Commonwealth tried to catch up quickly in the last 30 years of its existence, but only partly succeeded.

Rich noble families started factories in the early 1700s. This grew even more in the second half of the century, with city business owners also playing a big role. King Stanisław August Poniatowski helped a lot with factories, mining, and business funding from the start of his rule. Workshops were most common in western Poland, Danzig, Warsaw, and Kraków. Iron production was the most important heavy industry. The late 1700s also saw heavy industry grow in Upper Silesia.

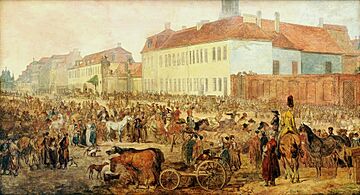

City business owners became stronger because trade improved. The King helped end the nobles' control over trade. This allowed city merchants to gather more money. However, Prussia, Austria, and Russia made trade difficult for the Commonwealth. They charged high taxes and fees. To help trade, the state built or improved roads and waterways. Lending money, once centered in Danzig, now happened mainly in Warsaw and Poznań. The huge wealth of banker Piotr Fergusson Tepper, who was not a noble, showed how times were changing.

The Commonwealth bought more goods than it sold until the 1780s. Danzig's role in trade decreased partly because Prussia bothered the city. Prussian policies also hurt trade between Silesia and the Commonwealth. Warsaw became the new main trade center, boosting trade within the country. Other regional centers like Cracow served western Poland. The First Partition reduced trade with southern Poland and Pomerelia, which were taken by Austria and Prussia.

Society Changes and a New Nation

Population Shifts and Peasants

Society in the Commonwealth began to change during the three partitions. These changes affected peasants, city dwellers, and nobles. The country's ethnic makeup also changed as its territory shrank.

The population was about 7 million in the early 1700s. It grew by a few million by the time of the First Partition. Western Poland was much more crowded than the eastern areas. After the Second Partition, the country was much smaller (from 730,000 km² to 200,000 km²). It had only 4 million people. Before the partitions, peasants made up three-quarters of the population. City people were 17-20%, and nobles and clergy were 8-10%. Two-thirds of the people were Polish or had adopted Polish culture. Minorities were mostly non-nobles.

Many Poles also lived outside the Commonwealth's borders, in areas like Upper Silesia and parts of East Prussia. Germans were a minority in western and northern Poland, except in some specific areas. Jews were spread throughout the country, especially in cities, where they were active in trade. The First Partition meant that just over half of the Commonwealth's population was Polish. Half of all Poles now lived in Prussia and Austria. These countries tried to make Poles adopt German culture.

Improving the lives of peasants became a main goal for reformers, including the King. In 1768, the sejm stopped feudal lords from executing their serfs. But an attempt to give peasants more rights in the 1780 Zamoyski Code failed. Only in 1791 did the May 3 Constitution protect peasants by law. A stronger, but short-lived, effort to help peasants was the Proclamation of Połaniec in 1794.

About 64% of peasants lived on private noble estates, where conditions varied. Peasants on royal lands (19%) and Church lands (17%) saw more improvements. The late 1700s saw some peasants become very poor, while others became wealthy. Education for rural serfs improved slowly, despite efforts by the Commission of National Education. When the country was in danger, some peasants helped defend it during the Bar Confederation and even more during the Kościuszko Uprising.

City Dwellers and Nobles

Like in other European countries, the Enlightenment helped the city dwellers (burghers) in Poland. The richest of them were business and professional people. Their economic power grew, and they wanted more political power. In the mid-1700s, towns were in bad shape, especially in Lithuania. In western Poland, about 30% of people lived in cities. In eastern areas, it was less than 10%. Danzig, the biggest city, had fewer than 50,000 people. Warsaw had less than 30,000.

Thanks to state protection and a better economy, things improved in the last decades of the Commonwealth. Warsaw grew to over 100,000 people by 1790. Other cities like Cracow and Poznań reached 20,000.

In 1764, commissions were set up to improve city economies. But real changes came during the Great Sejm. From 1775, nobles could work in "city professions." In 1791, city dwellers in royal cities could buy rural land. They also gained court rights and access to state jobs and the sejm. Nobles were now allowed to hold city government jobs. City self-governing groups were protected by law. This was better for Polish city dwellers than for those in areas taken by Prussia, who faced Germanization.

Early capitalist growth created new social groups in cities. These included the rising intelligentsia (educated people), rich bankers, and factory owners. There were also many poor people, the beginning of the working class. The laws of 1764, 1791, and 1793 mostly helped rich and educated city people.

City dwellers became more important in culture. This started with German-influenced thinkers in Danzig and Toruń in the mid-1700s. It ended with wealthy Warsaw citizens who built palaces and supported arts. The scientist and writer Stanisław Staszic, a key figure in the Polish Enlightenment, was the most famous non-noble intellectual. City intellectuals, often from poor noble families or city families, spread Enlightenment ideas. Many strong supporters of reform and leaders of the Kościuszko Uprising came from this group. Many city sons went to top schools in Poland and abroad. Radical ideas were popular among Warsaw's lower classes. This group strongly supported the Great Sejm's reforms and French Revolution ideals. They became very important during the Uprising.

Most nobles (szlachta) wanted to keep their special rights. They opposed reforms in King Stanisław August's early years and rejected the Zamoyski Code. Many joined the anti-reform Targowica Confederation in 1792. The richest nobles (magnates) were very different from regular gentry. Their lands were often split by the partitions. Many magnates served foreign interests, though some, like Andrzej Zamoyski and Ignacy Potocki, were reformers. The middle nobility suffered more from the First Partition in Prussian and Austrian areas. They also lost a lot during the Bar Confederation revolt. Most older gentry followed traditional ways. But younger nobles, closer to Warsaw, were inspired by foreign styles, especially French fashion and Enlightenment ideas.

After the First Partition, out of 700,000 nobles, 400,000 were poor nobles. They owned little or no land and were losing their status. The work they used to do for the rich (like serving in private armies) was no longer needed. These poor nobles held onto their noble rights as long as possible. But they often had to become hired workers or move to cities. In 1791, the Great Sejm required a minimum yearly income from rural property to vote in local assemblies.

Society became more equal in some ways. New laws made it easier for rich city dwellers to become nobles. Now, social status depended more on wealth. The growing Freemasonry movement in the late 1700s, which included important people of all classes, helped spread ideas of equality. The idea of a nation as a community of all social classes began to take hold, even among noble thinkers.

New Ideas and Arts

Education and Science Progress

Major education reforms aimed to create educated citizens who cared about public matters. These reforms greatly helped the Polish Enlightenment. The Commonwealth became an active center of European culture again. As Poland's existence was threatened, education was seen as a way to change the thinking of the ruling nobles. It aimed to teach them civic duties and help them make necessary reforms.

Important reforms in Jesuit and Piarist schools began in the 1740s. Before the First Partition, there were about 104 church-run colleges. 30 to 35 thousand students attended classes nationwide. But the Church's power was weakening as French Enlightenment ideas spread. It was time for the state to take over and make schooling secular, like in other European countries.

The first non-religious school in Poland was the "School of Knighthood" in 1765. It trained military officers and was led by the enlightened nobleman Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski. Many future military leaders, including Tadeusz Kościuszko, studied there.

A big education reform became possible after the Jesuits were suppressed. They ran most colleges at the time. In 1773, the sejm created the Commission of National Education to lead this reform. The Commission took over Jesuit schools, property, and money. Members included Andrzej Zamoyski and Ignacy Potocki. Educators like Hugo Kołłątaj also helped. The Commission reformed all levels of education, from elementary to higher. It introduced new, secular teaching programs.

The two main universities, Kraków Academy and Wilno Academy, supervised secondary education. Both were undergoing big reforms. In Cracow, Kołłątaj led the reform. He added departments, especially in math and science. He focused on practical uses of subjects and made Polish the main teaching language. The "Main School of the Crown" became a creative science center again. Marcin Odlanicki Poczobutt successfully reformed the university in Vilnius. Former Jesuit teachers mostly cooperated with the new rules in secondary schools.

Many other schools were directly under the Education Commission. Their approved programs focused on exact sciences, the national language, history, and geography. Latin was limited, and theology was removed. "Moral science," which aimed to create responsible citizens, was no longer based on Catholic religion. There were also many parish schools, influenced by the Commission's work. The Society for Elementary Books, founded in 1775, produced 27 modern textbooks.

Education for peasants improved very slowly. There were about 1600 parish schools in 1772, half of what they used to be. More rural schools were opened during the Great Sejm era, and more girls attended.

The Commission of National Education's work was the greatest cultural achievement of the Polish Enlightenment. Conservatives criticized the reforms, but the new policies stayed in place. Poland became one of the leading European countries in education quality at the university and secondary levels. The Commission greatly influenced society's attitudes for many years.

Education also improved in lands taken by Prussia and Austria after the First Partition. General education became more available for non-nobles. But knowing German was needed for more than basic education.

Science, based on rationalism and empiricism, became less dependent on religion. It sought to understand nature and society better. The goal was to rebuild society and use natural resources through knowledge. This meant a strong focus on practical science. Modern science had developed in Western Europe since the late 1600s, when the Commonwealth was falling behind. So, Poland had to catch up in the late 1700s.

Marcin Poczobutt in Vilnius and Jan Śniadecki in Cracow did advanced astronomy research. Mathematicians included these two and Michał Hube. Jan Jaśkiewicz and Józef Osiński were chemists interested in industry.

Among naturalists, Jan Krzysztof Kluk was outstanding. He studied and described Poland's flora and fauna and applied his knowledge to farming. Mapping the Commonwealth was a big project with military uses, led by the King. Karol de Perthées only finished maps of the western part. Jan Potocki traveled widely and wrote great travel stories. Medical knowledge grew mainly at the two universities, which were modernized. Key figures were Andrzej Badurski and Rafał Czerniakowski in Cracow.

Antoni Popławski and Hieronim Stroynowski were economists who believed in physiocracy (the idea that wealth comes from land). Leading thinkers Hugo Kołłątaj and Stanisław Staszic also supported physiocracy. But they also favored state protection for industry and trade. The state was supposed to protect peasants, who created farm wealth, and help industry and trade grow.

Modern history was developed by Feliks Łojko-Rędziejowski, who used statistics, and especially Bishop Adam Naruszewicz. Naruszewicz wrote a History of the Polish Nation up to 1386. He also collected valuable historical materials and criticized the destructive politics of the nobles.

The Polish Enlightenment's science contributions were smaller than during the Renaissance. But efforts to spread science and knowledge showed its new social role. Many textbooks, translations, and magazines were published. The Historical-Political Diary by Piotr Świtkowski was a good example.

Literature and Arts

Polish literature during the Enlightenment mostly aimed to teach. Its main style was classicistic and rationalistic. There were many strong debates, often using satire. Franciszek Bohomolec and Adam Naruszewicz wrote satires. Bishop Ignacy Krasicki wrote the best ones. Krasicki, called the "Prince of the Poets," also wrote early Polish novels like The Adventures of Nicholas the Experienced. These books were meant to teach. He was a major writer and part of King Stanisław August Poniatowski's inner circle. Krasicki's satires Monachomachia and Antymonachomachia made fun of Catholic monks. Another poet from the King's circle was Stanisław Trembecki.

Bohomolec edited the magazine Monitor for a long time. It criticized social and political issues in the Commonwealth. It promoted good citizenship. Nobles dominated Polish society and culture. Reformers realized that a model citizen in Poland had to be an "enlightened Sarmatian" (a modern, progressive nobleman). Krasicki explored this idea in his works. It fully developed during the Great Sejm era.

Much of the intellectual life happened around the royal court. Leading writers, artists, and scientists attended the Thursday Dinners at the Royal Castle in Warsaw. The King hosted these dinners. He generously supported intellectuals. They discussed their interests and important state matters. The King's involvement helped spread European Enlightenment ideas in the Commonwealth.

Other centers of art and politics became important as public feelings grew more radical. Foreign control and the partitions were very upsetting. New places for creative work appeared. Hugo Kołłątaj's Kuźnica (Kołłątaj's Forge) during the Great Sejm was one such group. They wanted to be separate from the royal court. Other new writers were supported by rich city dwellers. They became very influential among enlightened nobles and the public in Warsaw. They often came from poor noble families. Their writings mixed literature and political journalism, published in many pamphlets. Franciszek Salezy Jezierski was a leading critic of the noble government and a defender of the lower classes. Jakub Jasiński was a poet and general during the Kościuszko Uprising. He was a leader of the leftist Polish Jacobins. More radical political writers rejected the idea of a "noble nation." They appealed to all people, stressing the importance of peasants and city workers in the fight for independence.

Another literary style was influenced by French Rococo and sentimentalism. This style became popular in Europe after Jean-Jacques Rousseau's novels. In Poland, folk elements and peasant creativity were used in sentimentalist works. The most successful lyrical poets were Franciszek Dionizy Kniaźnin and Franciszek Karpiński. They later influenced Polish Romantic writers.

The Czartoryski noble family supported sentimentalist writers and artists. They were related to the King but kept their distance. In the 1780s, they created a major cultural center at their home in Puławy. Izabela Czartoryska's English garden there was designed to look like wild nature. The Czartoryskis wanted to influence and reform the nobles, but in a different way than the King. They focused on Poland's history and the need for it to become a modern state.

The Enlightenment also brought back Polish national theater. Polish language plays started in Warsaw's main theater in 1765, thanks to Stanisław August. The first full Polish plays were the patriotic The Return of the Deputy by Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz (1790) and the folk-inspired Krakowiacy and Górale by Wojciech Bogusławski. The latter was an innovative opera staged just before the Kościuszko Uprising.

In music and visual arts, there was a link to the earlier period. Kings and nobles supported painters, sculptors, architects, and musicians of various nationalities.

The Ogiński noble family loved music. Two famous composers came from this family: Michał Kazimierz Ogiński and Michał Kleofas Ogiński. Maciej Kamieński, a Slovak living in Poland, wrote the first Polish opera, Misery Contented, in 1778. The Czech Jan Stefani wrote the music for Krakowiacy and Górale. Besides operas, instrumental music became more popular. This showed a general shift towards secular artistic tastes.

In architecture and painting, classicism was the main style. But other styles were also present. Baroque and Rococo works continued in the late 1700s. Styles similar to literary sentimentalism appeared later.

Churches and monasteries were mostly built in the Baroque style until the late 1700s. Rococo architecture appeared at the start of the Polish Enlightenment. It created finely decorated, more private rooms. Rococo is seen in the Mniszech family complex in Dukla and the Ujazdów Castle in Warsaw, rebuilt by Efraim Szreger.

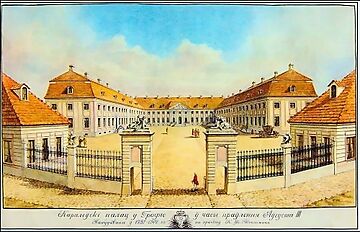

French-influenced classicistic buildings were symmetrical, single structures. They often had columns and central domes. King Stanisław August's artistic taste led to these buildings in the 1760s. He had the Royal Castle interior redone. After 1783, the summer Łazienki Palace was rebuilt in classicism by Domenico Merlini. Łazienki park had sculptures by André Le Brun. The Protestant Holy Trinity Church in Warsaw was modeled after the Pantheon in Rome. The classical style was copied in many city homes and noble palaces. The typical noble manor house, with a triangular roof over the entrance, was created then.

The Warsaw castle and Łazienki Palace were decorated with paintings by Marcello Bacciarelli. He also painted many portraits, including Polish historical ones. He inspired many talented young Polish artists. Jean-Pierre Norblin, a French painter brought to Puławy by the Czartoryskis, created many unique and realistic scenes of current events, history, and landscapes. His art greatly influenced the 1800s. Among Polish painters, Franciszek Smuglewicz and Józef Peszka, professors in Vilnius and Cracow, were key figures. Tadeusz Kuntze worked mostly in Rome, and Daniel Chodowiecki in Berlin.

First Reforms and First Partition

Bar Confederation and First Partition

The laws passed by the Repnin Sejm ended the reforms attempted by the Familia (a powerful noble family). But they didn't bring peace. Repnin's harsh rule angered both powerful nobles and regular gentry. They felt their "freedoms" were under attack. While the Sejm was still meeting, the Bar Confederation formed on February 29, 1768, in Bar. Its goals were to protect the Catholic religion, noble privileges, and state independence. The local nobles were soon joined by others and some military forces. Józef Pułaski, the Confederation's Marshal, had only 5,000 poorly equipped men. They were quickly defeated by Russian and Polish royal forces. The confederates surrendered in Berdychiv and Bar. Their leaders and remaining army found refuge in Moldavia (Ottoman Empire). But unrest continued for several more years (1768–1772).

A pamphlet called Suplika of Torczyn spread in Volhynia in 1767. It asked for help and rights for peasants. This added to tensions among rural people. It led to the Koliyivshchyna, a Ukrainian peasant revolt in 1768. This revolt started as the noble uprising in Podolia was ending. Peasants were restless due to rumors about the Uniate Church taking over the Eastern Orthodox Church. They also heard that Empress Catherine supported a war against Polish landowners. The Confederation forces also committed abuses. Peasants were also burdened by the expansion of large farms (folwark) eastward. They violently attacked nobles and their Jewish managers. The worst losses happened in Uman. The Ukrainian uprising, led by Cossack commanders Ivan Gonta and Maksym Zalizniak, was brutally put down by Polish and Russian forces. But it caused unrest elsewhere and stopped the confederates from getting large-scale peasant support.

Meanwhile, the noble challenges grew stronger. New confederations formed in western Poland and Lithuania. A rebellion in Kraków ended after a month-long siege. But it was clear the fighting would continue. The Russo-Turkish War in October 1768 gave the confederates new hope. France, wanting to weaken Russia, encouraged the Ottoman Empire to fight Russia. France also supported the confederates with money, weapons, and soldiers. Austria gave refuge to the confederate leaders.

However, the confederates had different goals. The powerful nobles wanted to remove Stanisław August and replace him with a Wettin ruler. The leaders declared the King's dethronement in 1770. The middle nobility fought for national independence. But they also wanted to keep their own privileges and those of the Catholic Church. This limited the appeal of their cause. About 200,000 people served in the uprising, but only 10,000 to 20,000 at any time. The cavalry lacked equipment and training. The army lacked unified command and enough foot soldiers. The confederates, though willing to sacrifice, were no match for the Russian army. Their strategy of small, scattered attacks ruined the country without a real chance of victory.

In late 1770, the confederates, led by French adviser General Charles François Dumouriez and commander Kazimierz Pułaski, tried to set up a defense line along the upper Vistula River. But they only held Lanckorona and Tyniec for a while. Attempts to restart fighting in Lithuania failed. Józef Zaremba had only temporary success in western Poland. The failed kidnapping of the King in 1771 reduced support for the Confederation. In 1772, foreign armies entered the country for the partition. The movement was ending. The Wawel Castle garrison resisted, and then the Częstochowa fortress under Kazimierz Pułaski held out until August 18. The uprising ended, and the confederate leaders left the country.

The Bar Confederation forced Russia to rethink its strategy. Russia, busy with its war against Turkey, agreed to reduce its Polish ally's territory. This was pushed by Frederick II of Prussia. This led to the First Partition.

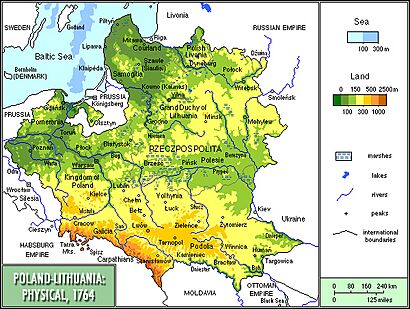

Prussia, having conquered Silesia, wanted to expand towards the Vistula River mouth and Royal Prussia. But Austria took the first steps. In 1769, Austria took Spiš, and in 1770, other counties. Frederick then took his own lands. When Catherine II was ready, the three powers started partition talks. The Russian-Prussian agreement was signed in early 1772, and Austria joined. The new borders were set on August 5, 1772. The agreement said the Commonwealth was decaying, with anarchy and factions. This was used to justify taking its lands. Austria and Prussia eagerly took large parts of Polish lands. The eastern parts of Lithuania taken by Russia were less important.

Prussia gained Warmia, Pomerelia, Malbork Voivodeship, Chełmno Land, and the middle-upper Noteć River basin. This was 36,000 km² with 580,000 people, but without Gdańsk and Toruń. Austria took southern parts of the Kraków and Sandomierz Voivodeships and the Ruthenian Voivodeship. This was 83,000 km² and 2.65 million people. Vienna called this area Galicia and Lodomeria. The Russian partition was 92,000 km² and 1.3 million people. The Commonwealth's army, at most 10,000 men, did not resist.

The first partition left a still existing Poland-Lithuania. It became a buffer state. But its economic power was greatly reduced. Prussia controlled the lower Vistula, meaning Polish farm exports. Austria took the salt mines. Many Poles now lived in Prussian and Austrian states. They faced pressure to adopt German culture. This lowered the percentage of Poles in the remaining Commonwealth.

The partitioning powers demanded that the Commonwealth officially approve the partition. They threatened more land grabs if it refused. King Stanisław August appealed to European courts. But only a few people, like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, condemned the partition. The "Partition Sejm" was called in 1773. Despite objections from some deputies, it was forced to approve the partition. Unfair trade agreements, especially with Prussia, were also imposed. The partitioning powers clearly intended to interfere in Polish affairs. The future of the Commonwealth looked bad.

The Partition Sejm of 1773-1775 also made some limited but important improvements to the state's political system. Frederick II and Russian leader Nikita Ivanovich Panin had already decided not to allow big changes to the "cardinal laws." Their view was represented by Gédéon Benoît and the new Russian ambassador Otto Magnus von Stackelberg. The Polish opposition and reform groups were exhausted. Bar Confederation activists had left or were exiled. The Familia and the King lacked popular support and Catherine's trust. So, less important people took the lead, like Marshal Adam Poniński.

To prevent disruptions from the liberum veto, the Sejm was set up as a confederation. A special group was formed to prepare new laws. The main debate was about creating a Permanent Council (Rada Nieustająca), an executive government. This was clearly needed. A group of powerful nobles wanted to limit the King's power. But Stanisław August convinced Russia that an efficient government was needed. He created a council that limited some of his powers, but even more so the power of the very strong noble ministers. The Council, set up in 1775, was led by the King. It had 36 elected members and made decisions by majority vote. The King decided in case of a tie. Ministers were supervised by five departments: Foreign Interests, Police, Military, Justice, and Treasury. The Council also suggested three candidates to the King for Senate and other main offices.

The army was to be increased to 30,000 men and funded by new taxes. But economic problems prevented this. The state could only keep half the planned army.

The one clear achievement of the 1773-1775 sejm was the creation of the Commission of National Education. This modernized the country's education system. Nobles were allowed to work in "city" professions. Improvements for peasants were discussed but not acted upon. The cardinal laws were re-established. Foreigners and children of a ruler were forbidden from becoming king. The new laws were guaranteed by all three partitioning powers.

The Rada Nieustająca (Permanent Council) was challenged by noble opposition led by Franciszek Ksawery Branicki. They tried to discredit the new power structure (King, Council, Ambassador Stackelberg) to the Empress. Their efforts failed. In 1776, the Military Department of the Council took control of the army. The power of the traditional military commanders (hetmans) was greatly reduced. The King would nominate officers and command the Guard. The goal of increasing the military size was eventually dropped.

The reforms of the Partition Sejm, though hindered by plots and never fully implemented, became the necessary base for the "Republic Enlightened" movement. This was true even though this sejm lacked enlightened leaders, unlike those who would soon appear during the Great Sejm reforms.

Great Sejm and May 3, 1791 Constitution

Reform Efforts and Proposals

Attempts to reform and save the Commonwealth had only partly succeeded. The country had lost land. It became clear that bigger changes needed younger, enlightened nobles and more middle nobility to support them. This was hard, as most powerful nobles still opposed the King. And the lower nobility tended to be conservative.

A big fight happened over the Zamoyski Code. Andrzej Zamoyski, a former high official, was asked by the 1776 sejm to create a unified law code. Reformers like Józef Wybicki helped him. Wybicki wrote Patriotic Letters in 1777. He explained the main ideas: strengthening the central government and improving relations between social classes, especially for city dwellers and peasants.

The proposed code dealt with some of these issues. It didn't remove the nobles' basic privileges. For example, larger cities could send a few representatives to sejm meetings. And, what critics found very offensive, mixed noble-peasant marriages would be allowed. Papal orders could only be published with state permission. This led the Papal Nuncio to strongly oppose the laws. Propaganda easily convinced the noble deputies, and the 1780 sejm rejected the Code loudly.

In the 1780s, the noble ruling class became more divided. But the reform group grew stronger. Many people saw that changes were needed. The most conservative nobles wanted to completely break up centers of power. But their progressive young generation increasingly supported real reform. Political unrest also grew among other social classes. This led to many published debates. Informal groups, like the salons led by Izabela Czartoryska or Katarzyna Kossakowska, and Freemasonry, were active.

Before the Great Sejm, the writings of independent scientists and reformers Stanisław Staszic and Hugo Kołłątaj were very important. Both were Catholic clergy. But they sometimes took radical social positions.

Stanisław Staszic (1755–1826) came from a city family in Piła. He studied a lot abroad, especially in Paris. He became a teacher for Andrzej Zamoyski's children. He published two important works: Remarks on the Life of Jan Zamoyski (1785) and Warnings for Poland (1787). Staszic wanted a stronger king, hereditary succession, majority voting in the sejm, and equal representation for city dwellers and nobles. The army needed to be bigger. Social and economic policies were most important to him. He wanted to protect local trade and crafts. The oppressed peasants needed state protection and reform of their labor. He saw their condition as the main reason for the Commonwealth's weakness. Staszic blamed the powerful nobles for the country's bad state.

Hugo Kołłątaj (1750–1812) was more of a political activist. He came from middle nobility in Volhynia. Kołłątaj studied in Rome. He then worked actively for the Commission of National Education, especially reforming the Kraków Academy. He wrote Anonymous Letters to Stanisław Małachowski and Political Right of the Polish Nation (both by 1790). Kołłątaj's views were similar to Staszic's. He was more flexible in his tactics. During the Great Sejm era, he became the main leader of the Patriotic Party. He was less radical than Staszic on social issues. But Kołłątaj said, "the land where man is a slave cannot claim freedom." His main concern was reforming the national government. Some of his ideas were included in the Constitution of May 3, 1791, which he helped write.

The young Józef Pawlikowski strongly defended the serfs. He wrote On Polish Subjects (1788) and Political Thoughts for Poland (1790). He also supported a strong king, limiting noble excesses, and political rights for city dwellers.

The Kołłątaj's Forge group strongly expressed anti-noble feelings. They condemned the near-anarchy caused by noble privileges. They often used ideas from the early French Revolution. Franciszek Salezy Jezierski published Sieyès' What Is the Third Estate? in Polish in 1790. The French bourgeois program was adopted and adapted to the Commonwealth's situation. It was used as another argument for improving the Republic.

Great Sejm and May 3, 1791 Constitution

The success of the reform program depended on enough support at home. It also needed a good international situation in central-eastern Europe. Breaking the Russian-Prussian alliance was very important. The War of the Bavarian Succession (1778–1779) and the Austro-Prussian conflict didn't improve the Commonwealth's situation. The United States War of Independence then became a global issue. It drew attention away from West European interests. Many Poles, including Tadeusz Kościuszko and Casimir Pulaski, fought for the American colonists.

A new situation in Europe arose after Russia took Crimea and Frederick II died. Prussia, allied with Britain and the Netherlands, became hostile to Russia. Russia and Austria seemed to threaten the Ottoman Empire. Amidst military and diplomatic moves, Poland was encouraged to work with Prussia and oppose Russia. Some Polish circles were interested in this.

There was a self-proclaimed Patriotic Party. It was led by nobles who liked Britain and Prussia. They were annoyed by Russian interference in the Commonwealth. They opposed King Stanisław August and his pro-Russian policies. This group included members of the Puławy group: Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski, Ignacy and Stanisław Potocki, and their associate Scipione Piattoli. They hoped a Polish-Prussian alliance would help them regain lands lost to other powers, especially Austria. Another group of influential nobles was led by Seweryn Rzewuski, Franciszek Ksawery Branicki, and Szczęsny Potocki. They wanted to overthrow the King with Russian help and create a decentralized republic ruled by nobles.

Stanisław August himself went to Kaniv in Ukraine in 1787 to meet Empress Catherine. He hoped she would agree to a larger Polish army and more power for him. In return, he offered help in Russia's war with the Ottoman Empire. The Empress wasn't ready to make concessions then. But the next year, due to war difficulties, Russia proposed a defense treaty. It suggested Polish troops join the war. To formalize the alliance and strengthen the army, the King called a sejm in Warsaw in the fall of 1788.

A confederation was set up. It was led by the marshals, Stanisław Małachowski and Kazimierz Nestor Sapieha. Unexpectedly, the Great Sejm lasted four years.

The pro-Russian group, meant to achieve these goals, was ineffective. It included a divided, conservative anti-King faction (like Branicki and Rzewuski) and the King with his "court party." The King's supporters, like Chancellor Jacek Małachowski, saw an alliance with Russia as necessary.

The lack of unity in the pro-Russian group was used by the patriotic group. They were likely more numerous. They wanted reforms and independence from Russia with Prussia's help. The Puławy group and Stanisław Małachowski belonged here. They were often guided by Hugo Kołłątaj, who wasn't a sejm deputy. The patriotic group became dominant in the Sejm. They eventually convinced the King to join them and passed most of their laws.

The early events of the French Revolution happened while the Great Sejm was meeting. As feudal interests in Europe were threatened, Poland paid close attention to city writers. City leaders wanted to use the situation. Advised by Kołłątaj, Jan Dekert, President of Warsaw, called representatives from 141 royal cities to Warsaw in November 1789. They signed the "Act of Unification of the Cities." They formed the Black Procession, which marched to the Royal Castle. They gave their demands for more political and economic rights for city residents to the King and the Sejm. Peasant unrest in 1789 also added to fears of revolution spreading to the Commonwealth. The sejm debate, against this background, soon led to big decisions.

Prussian ambassador Ludwig Heinrich Buchholtz suggested replacing the Polish-Russian alliance with a Polish–Prussian alliance. Many sejm deputies saw this as a good chance to get rid of Russian control. The Prussian offer was accepted, despite opposition from the King and Ambassador Otto Magnus von Stackelberg. Anti-Russian laws were passed. The army would be greatly enlarged to 100,000 men. Control over the military was taken from the military commanders and the Permanent Council. A new Military Commission was created. The Permanent Council, seen as a tool for Russian interference, was then removed. Strict neutrality was to be observed in Russia's war with the Ottoman Empire. Foreign forces were to leave the Commonwealth.

The general excitement for reform wasn't matched by a readiness to provide resources. The partly reformed military had only 18,500 soldiers in 1788. To enlarge it, much better finances and conscription were needed. After a delay, in 1789, the Sejm passed a permanent 10% tax on noble profits, 20% on Church income, and other tax reforms. City taxes were increased. But many rural landowners refused to pay. The Sejm had to reduce the army goal to 65,000. Anachronistically small numbers were planned for foot soldiers (about 50%). This was to provide jobs for noble volunteers in the cavalry.

Negotiations with Prussia continued under the new envoy Girolamo Lucchesini. The treaty was signed on March 29, 1790. This was despite disagreements over Gdańsk and Toruń, which Prussia demanded but the Sejm wouldn't give up. However, Prussia soon lost interest in the alliance. The international situation changed, including Austria withdrawing its threat to the Ottoman Empire. For Prussian politicians, working with Russia again seemed best for gaining more Polish land.

The "patriots" in the Sejm went ahead with reform plans anyway. The Deputation for the Betterment of the Form of the Government was appointed in 1789 to speed up preparations. The King now joined the patriotic group and participated. The Sejm was not dissolved after its two-year term. Elections were held in fall 1790 to add more deputies. The planned reforms had generally gained popularity. Nearly two-thirds of the new deputies joined the reform process. It seemed to have broad support.

Local assemblies (sejmiks) were reformed first. Only propertied nobles could vote there. This took away much of the powerful nobles' traditional control. But it also violated the formal equality of nobles. The Free Royal Cities Act, passed on April 21, 1791, was very important. It met the demands of the Black Procession. City dwellers gained personal legal protection, access to offices, the right to buy rural land, independent self-government, and limited representation in the sejm. It became easier for city dwellers to become nobles. Nobles were allowed to trade and work in cities or hold city offices. Private towns were not included. Full equality of the two classes wasn't achieved. But this breakthrough law made clear progress in politics, society, and economy. Much of the conservative opposition no longer participated in the sejm debate. The laws passed with little resistance.

The most important reform was done by the patriots and the King on May 3, 1791. It was like a quick takeover. The main government law was prepared in secret. Only a few deputies knew its details. It was written mainly by Stanisław August, Scipione Piattoli, Ignacy Potocki, and Hugo Kołłątaj. Against parliamentary rules, the assembly wasn't told about the proposal in advance. The law was rushed through before many deputies could arrive (only about one-third were present). The session happened under pressure from many Warsaw residents. Alarmist reports from abroad were read. The King declared the law needed immediate acceptance. One deputy protested dramatically. But then the Constitution was accepted and sworn in among a cheering crowd. The next day, a small group of deputies protested. But on May 5, the matter was officially closed, and protests were ignored. This whole event happened, for the first time in the 1700s, without foreign military forces or pressure.

The main document was called the Government Statute (Ustawa Rządowa). It is often called the second oldest constitution of its kind, after the United States Constitution. It spoke of the country's "citizens." For the first time in Polish law, this included city dwellers and peasants, not just nobles. Nobility remained the privileged class. But this privilege was now mostly limited to those with land. Their power over peasants was somewhat reduced. Peasants were declared to be under the protection of the law and government. New settlers from abroad would have personal freedom. Landlords were encouraged to make contracts with their rural tenants, specifying obligations. The state could now intervene in the lord-serf relationship by enforcing contracts.

Government reform included further uniting the Crown of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Separate central institutions were removed. A common military and treasury were created. But legal differences remained. Lithuanian nobles would fill half of the central government offices. Ideas of Montesquieu's separation of powers were used as much as practical. The reformed sejm, still dominated by nobles, remained the main power. It had to be ready to meet every two years if called by the king or marshal. Decisions would be by majority vote. The liberum veto and confederations were removed. The senate's power was reduced to a temporary veto of laws passed by the main chamber. The king was no longer a separate "estate" of the sejm. Besides making laws and setting taxes, the sejm supervised other government parts. Local assemblies (sejmiks) became advisory. They couldn't force their delegates to do anything specific. A special constitutional sejm would meet every 25 years. It would have unique power to change the basic laws in the "National Constitution."

After over two centuries of elected kings, the new constitutional monarchy would become hereditary again. After Stanisław August's death, the Wettin family from Saxony would take the throne. The Henrician Articles would no longer bind the king or give nobles an excuse for rebellions. Government ministers answered to the sejm. They were members of the new central government body, the Guardians of the Laws (Straż Praw). This new council included the king as its head, the primate (a high church official), five ministers (police, internal affairs, foreign interests, war, and treasury). The marshal of the sejm and the heir to the throne also had advisory votes. Ministers were nominated by the king during a sejm session. The sejm could remove them with a no-confidence vote. The Guardians would supervise all other offices, working with sejm committees (police, military, treasury, and national education). Provincial civil-military commissions would continue. Courts were reformed and mostly became group decision-making bodies.

The Government Statute was influenced by Western thinkers like Montesquieu and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It also used British and American examples. But it was written specifically for the needs of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The "Enlightened Republic" was created. It could have been a good model for government and social reform in central and eastern Europe, if it had been allowed to continue.

Efforts to Defend Reforms and Independence

War with Russia and Second Partition

The Constitution's adoption was mostly welcomed in Poland and abroad. Most middle nobles and city dwellers supported it. Many peasants took the promise of state protection seriously. They were more willing to reject some unfair feudal duties. Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine praised the law. The Vienna court also supported the reform.

The conservative noble group, led by Stanisław Szczęsny Potocki, Seweryn Rzewuski, and Franciszek Ksawery Branicki, strongly opposed it. They got support from Empress Catherine. She was already worried about the French Revolution spreading to central and eastern Europe. She also worried the Commonwealth might become an ally of revolutionary France. The Empress, done with the Turkish war, wanted to stop the Polish "revolutionary disease" before moving against France. Prussia also wanted to prevent a stronger Commonwealth. Frederick Augustus I of Saxony was pressured to reject his claim to the Polish throne.

Branicki, Potocki, and Rzewuski prepared an act of confederation in April 1792 in St. Petersburg. It would cancel the May Constitution and bring back the old laws. Catherine ordered their confederation to be formed at Targowica in Ukraine. The Targowica Confederation then asked Russia for military help. On May 18, nearly 100,000 Russian soldiers entered the Commonwealth.

After recent partial military reforms, the King had 57,000 soldiers. More recruitment during the war increased this to 70,000. But new recruits were not well-armed or trained. 40,000 faced the Russians at the front. The rest were reserves. There were a few good commanders, but not enough mid-level officers. The Crown army was led by Prince Józef Poniatowski, the King's nephew. The Lithuanian force was led by Duke Louis of Württemberg. Stanisław August didn't believe Poland could win militarily. He wanted a show of force to improve his negotiating position. The armies were expected to delay the enemy and protect Warsaw.

Lithuania was lost first. Louis of Württemberg betrayed them and wouldn't fight. Other leaders were also ineffective. The unsuccessful Battle of Mir on June 11 effectively ended the campaign there.

The outnumbered Crown army avoided defeat. It retreated in order from the southeastern borderlands to the Bug River. On June 18, Prince Poniatowski led his soldiers to a victory at Zieleńce. This made the King create the Virtuti Militari medal for bravery. In mid-July, they tried to hold a defense line at the Bug River. Tadeusz Kościuszko bravely defended it at the Battle of Dubienka. Afterward, the army continued retreating towards the Vistula River.

The war was not lost. The young army fought bravely. Prince Poniatowski and his generals suggested a nationwide mobilization to stop the Russians and save independence. Austria and Prussia were fighting revolutionary France. Russia was the only enemy. However, Catherine II gave the King an ultimatum: join the Targowica Confederation. He agreed on July 24 and ordered an immediate stop to military action. Poniatowski, Kościuszko, and other officers resigned in protest. But the King's surrender wasn't strongly opposed by the nobles' "patriotic camp." Many patriots then left the country. The work of the Great Sejm was undone. The Commonwealth was now ruled by Empress Catherine and the Targowica alliance.

The King hoped joining Targowica would save some reforms and protect the state's land. But this hope was false. Targowica leaders created a dictatorship. They ignored the King and his supporters. They destroyed many achievements of the Polish Enlightenment and reform era. Disoriented nobles joined the perceived victors in large numbers.

That victory was also an illusion. Prussia, defeated at Valmy by revolutionary France, demanded compensation. The defenseless Commonwealth's lands seemed available. Catherine II's advisers also thought it good to further reduce the Polish state. When the new Emperor Francis II opted out, expecting to gain Bavaria, a new partitioning treaty was signed on January 23, 1793, between Russia and Prussia.

Prussia received Gdańsk and Toruń, along with Greater Poland and western Mazovia. These lands had never been under German rule before (58,000 km² and over 1 million people). Russia gained most of Belarus, Dnieper Ukraine, and Podolia (280,000 km² and 3 million residents). Some Targowica leaders formally protested and left the country for a while. Others stayed to rule Lithuania under Russian authority. Danzig and Toruń militarily resisted the Prussian takeover.

The remaining Commonwealth was only 227,000 km² with 4.4 million people. It functioned as a Russian protectorate. The King had to arrange formalities to legalize the situation. A sejm was called to Grodno to do this and organize the smaller state. Deputies were chosen to be obedient. But strong protests still happened. Catherine's new ambassador, Jacob Sievers, responded with military force and punishment. The deputies eventually approved giving lands to Russia. But they wouldn't agree to a similar deal with Prussia. Sejm Marshal Stanisław Bieliński took their night-long silence as agreement. The treaty with Prussia was also officially announced.

The legal system returned to what it was after the First Partition. But majority voting in the sejm was kept, and city dwellers kept some of their new rights. The Cardinal Laws were back in force. The army was limited to 15,000. The Permanent Council was brought back for administration. But it was now under the Russian ambassador's direction.

Kościuszko Uprising and Third Partition

Uprising Preparations

After the Second Partition, patriotic Poles who wanted independence had only one choice: organize a broad national uprising. They hoped to ally with revolutionary forces in Europe.

The Second Partition brought not only political but also economic disaster. Land reductions disrupted markets, hurt industries, and caused a banking system crash. The state treasury was empty. This caused economic problems and social unrest. News of social uprisings came from France and also from Silesia in 1793.

The planned uprising had to be prepared carefully. They couldn't provoke the partitioning powers too early. But they also couldn't wait too long. Some foreign groups, including Austria from late 1793, wanted a final partition. Austria was unhappy about missing the chance to expand its territory earlier.

A radical conspiracy group, aiming for broad popular support, grew within the Commonwealth. It was led by former activists of Kołłątaj's Forge. Their goals included removing the King and creating a republic. Moderate elements, led by Ignacy Działyński and Warsaw banker Andrzej Kapostas, favored a carefully planned uprising based on the existing military. Their goal was to bring back the May 3 Constitution.

Leaders who left the country were also divided. Hugo Kołłątaj, helped by Franciszek Ksawery Dmochowski and Ignacy Potocki, published On the establishment and fall of the May 3 Constitution in Dresden. In it, they blamed the King, preparing for his overthrow. The main radical group of exiles hoped for quick social reforms. This would involve many people in a national uprising. They also counted on foreign help, especially from revolutionary France.

However, the international situation wasn't good. The Girondists and then the Jacobins in France were trying to get Prussia out of the war with France. Tadeusz Kościuszko, expected to lead the uprising, tried to get promises of aid. But he received no specific assurances during his stay in Paris in early 1793. Even during the uprising, its representative in Paris was denied help.

General Kościuszko attended the Polish reformist Corps of Cadets. He studied military engineering in Paris. He had already served with distinction in the American Revolutionary War and the recent Polish war with Russia. He wanted to use his American experience. He planned to combine regular army operations with informal popular forces, like peasants and city dwellers. He hoped their large numbers and motivation would make up for lack of equipment and training.

Early Uprising and Successes

During advanced preparations, the uprising plot was discovered in Warsaw by Russian ambassador Iosif Igelström. He arrested activists and sped up the reduction of the Commonwealth's armed forces. Some Polish forces were disbanded, others joined the Russian army. Brigadier Antoni Madaliński, stationed in Ostrołęka, refused to cooperate. He marched his unit towards Kraków to join Kościuszko, who was already there. Igelström ordered a pursuit. He also evacuated Kraków to concentrate Russian forces in Warsaw. Kościuszko arrived in Kraków. On March 24, 1794, he officially declared the act of the uprising in the main town square.

Tadeusz Kościuszko took on dictatorial powers. He promised to use them to regain national independence, defend borders, and promote freedom. He put off big system reforms for later. His main goal was military fight for "freedom, land, and independence." All men aged 18 to 28 were urged to join the insurgent army. Towns and villages were to get weapons for self-defense. Within a week, 4,000 soldiers and 2,000 kosynierzy (peasant fighters with scythes) gathered.

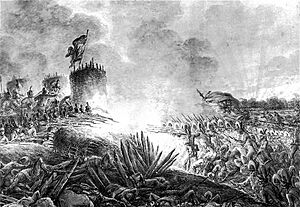

Kościuszko tried to move his forces to Warsaw. But a strong Russian force blocked him. Trying to go around that army, Kościuszko met a smaller Russian group. The Battle of Racławice happened. It was won with a brave charge by the kosynierzy. It didn't open the way to Warsaw. But it lifted the spirits of the insurgents. A Polish legend was born. Kościuszko showed his support for peasants. He became a symbol of their cause and national unity.

Meanwhile, the uprising spread to other regions. A division in Lublin and Volhynia joined in late March. An uprising happened in Warsaw on April 17. Russian authorities tried to disarm the Polish garrison there. Heavy fighting broke out with Warsaw residents, led by Jan Kiliński, a shoemaker. The Russian garrison was mostly destroyed. Ambassador Igelström barely escaped with his remaining forces. He found refuge with Prussian units outside the capital. With the victory in Warsaw, the military balance changed. The uprising spread to Mazovia and Podlasie.

Lithuania responded similarly from April 16. Fighting in Vilnius began on April 23. Russian units were also defeated there with popular help. The Lithuanian Highest Council was formed in Vilnius. It chose Jakub Jasiński, a "Jacobin" and successful military commander, as the leader in Lithuania. Targowica participants were dealt with harshly. Military commander Szymon Marcin Kossakowski was tried and executed.

Kościuszko was still in the Kraków region. He couldn't leave because of the Russian army. On May 5, he fortified a camp near Połaniec. He sought help from Warsaw and Lublin. The Russian general attacked Połaniec. But threatened with being surrounded, he withdrew on May 17 towards Silesia. Kościuszko could now communicate with Warsaw and influence events there more.

Social Basis and Insurgent Forces

The uprising leaders had to get the most social support possible. But they couldn't alienate the important noble class. The compromises they made didn't fully satisfy anyone. The Proclamation of Połaniec, issued by Kościuszko on May 7, set rules for serfdom and government protection for peasant workers. Peasants gained personal freedom to move. They couldn't be forced off their land. Their required labor was greatly reduced. This reform significantly improved peasants' lives. But its success depended on the goodwill of noble landowners, who often ignored it. Still, the contribution of kosynierzy units was very important. For example, 6,000 participated in the Battle of Szczekociny. About 800 peasant groups fought during the whole uprising. The slogan "they feed and defend" promoted the peasant cause.

Many nobles were suspicious about the uprising's social goals. Warsaw became a scene of sharp conflict between conservatives and revolutionaries. The Provisional Council was formed by moderates and people linked to the royal court. But they soon faced strong opposition from Warsaw crowds. These crowds were led by the Jacobin Club, formed on April 24. The Club's radicals wanted a popular revolution and harsh punishment for traitors. The "Jacobins" created a far-reaching plan for social and political reform. Riots happened on May 9. The Criminal Court was pressured to sentence four powerful nobles—Targowica participants, including Bishop Józef Kossakowski—to death.

At the end of May, Kościuszko replaced the Provisional Council with the new Supreme National Council. This council also included representatives from the left. Hugo Kołłątaj led the Treasury Department. Franciszek Ksawery Dmochowski took over schooling and propaganda. Revolutionary pamphlets were widely spread. Kołłątaj introduced long-overdue financial measures. The Commonwealth's goal of forming a 100,000-man military finally became real. The regular army reached only 55,000. The rest were auxiliary and volunteer groups, like general conscription and city militia. These were often poorly armed and trained. Efforts to develop an arms industry were only partly successful. But the insurgents' motivation was expected to make up for their lack of equipment. Kościuszko's non-traditional strategy of intense, rapid attacks aimed to harass the enemy and force hand-to-hand combat. This sometimes exceeded his forces' abilities.

Struggle for Warsaw and Defeat

As the Russians struggled to regain control and bring reinforcements, the insurgents were surprised by a Prussian intervention. Kościuszko, strengthened by units from the Lublin province, had 15,000 men. He tried to destroy the Russian force before it could join the Prussian army, but failed. He then decided to face the stronger combined enemy at the Battle of Szczekociny on June 6. The Poles were defeated and forced to retreat. The peasant hero of Racławice, Wojciech Bartosz Głowacki, died at Szczekociny. As a result, Kraków surrendered to the Prussians. General Józef Zajączek was also defeated at Chełm on June 8. He tried to stop a Russian force advancing from Volhynia. The insurgent armies retreated towards Warsaw.

Alarmed by these events, radical groups in Warsaw seized power. The Jacobins demanded strong action from the Supreme Council. The mob broke into prisons. Suspected traitors were killed without trials, and the King was threatened. Kościuszko reacted negatively. The riot leaders were severely punished. The left's attempt ended without a clear outcome.

Facing Prussian and Russian armies approaching the capital, Kościuszko led efforts to strengthen defenses. He actively involved Warsaw's population. The siege of the city and related skirmishes happened in July and August. From August 20, the uprising spread to the Prussian Partition, including Greater Poland, parts of Pomerania, and Silesia. As a result, Frederick II of Prussia, ready to storm Warsaw, withdrew on September 6. The Russians also lifted the siege. Jan Henryk Dąbrowski led a force to support the Greater Poland uprising. He took Bydgoszcz before having to return to the Bzura area. There, a division led by Józef Poniatowski also fought the Prussians.

In the east, the situation was less favorable for the insurgents. In June, fighting included Courland, and Liepāja was taken. But the Russians soon launched an offensive towards Vilnius. The Lithuanian capital surrendered on August 12. The army of Alexander Suvorov, stationed in Ukraine, was free to act. Suvorov moved west and destroyed Polish outer defense units at the Battle of Brest. The force of Ivan Fersen, previously withdrawn from the siege of Warsaw, crossed the Vistula to join Suvorov. They planned to attack the capital from the east. Kościuszko tried to prevent this joining of enemy forces. He decided to fight a defensive battle at Maciejowice against Fersen. Outnumbered two to one in men and cannons, Kościuszko counted on the timely arrival of Adam Poniński's force, which was nearby. Fersen attacked the insurgents on October 10, before Poniński could arrive. He defeated them and captured the wounded Kościuszko.

Kościuszko's capture caused a morale breakdown among leaders and fighters in Warsaw. Tomasz Wawrzecki, chosen as the new supreme commander, was not a military man. Suvorov stormed Praga (Warsaw's right bank district) on November 4. He killed all defenders and residents he could find. Warsaw surrendered, with King Stanisław August's help. The chaotic retreat of the insurgent army ended in surrender near Radoszyce on November 16.

Final Partition

After the Second Partition, the end of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was only a matter of time. The 1794 uprising was the last attempt to save the state. A huge military effort was made. But the nobles' resistance to fully implementing Kościuszko's social reforms left some human resources unused. The Kościuszko Uprising was dominated by the May 3 Constitution reformers. For most nobles, the Constitution's reforms were the most they would accept.

The uprising failed because Russia and Prussia had overwhelming military advantage. Possible outside support, from the Ottoman Empire or revolutionary France, never happened. Russia ended up settling partition disagreements between Prussia and Austria, which almost led to war. As Prussia left the anti-French alliance, Austria received Russian support. The Third Partition borders were agreed upon on October 24, 1795.

Prussia took most of Mazovia and Lithuanian lands up to the Neman River (48,000 km² and about 1 million people). Austria gained Lesser Poland up to the Bug River and parts of Podlasie and Mazovia (47,000 km² and 1.5 million). The rest, the remaining eastern and northern parts of the Commonwealth, went to Russia (120,000 km² and 1.2 million).

King Stanisław August Poniatowski gave up his throne. He had negotiated for his debts to be paid by the partitioning powers. He went to St. Petersburg, where he died in 1798. In St. Petersburg, the final agreement to formally eliminate the Kingdom of Poland, whose name was to be permanently erased, was reached on January 26, 1797.

The Third Partition happened without much European opposition. This was because the political situation was unfavorable for the Commonwealth. It was seen as linked to the French Revolution during its final years. A complete military takeover and end of a large state was a unique act of political violence in 18th-century Europe. But it meant that Poland's independence became a main problem in European politics during the 19th century.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la Mancomunidad polaco-lituana (1764–1795) para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la Mancomunidad polaco-lituana (1764–1795) para niños

- Ambassadors and envoys from Russia to Poland (1763–1794)

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |