Science in the medieval Islamic world facts for kids

During the Islamic Golden Age, roughly from 786 to 1258, amazing scientific discoveries happened in the Islamic world. This period saw great advancements in places like Baghdad, Córdoba, Seville, and Persia. Scientists made big leaps in many fields.

The most important areas were astronomy (the study of space), mathematics (numbers and shapes), and medicine (healing and health). But they also explored chemistry, botany (plants), agronomy (farming), geography (maps), eye care, pharmacology (drugs), physics (how things work), and zoology (animals).

Islamic science wasn't just about understanding the world; it also had many practical uses. For example, astronomers helped find the Qibla, the direction Muslims pray towards. Botanists like Ibn Bassal and Ibn al-'Awwam improved farming. Geographers like Abu Zayd al-Balkhi created accurate maps.

Mathematicians such as Al-Khwarizmi and Avicenna developed algebra, trigonometry, geometry, and Arabic numerals. Doctors like Abu Bakr al-Razi described diseases like smallpox and measles. They also challenged older Greek medical ideas. Scientists like Al-Biruni and Avicenna wrote about how to prepare hundreds of drugs from medicinal plants and chemicals. Physicists like Ibn Al-Haytham studied light (optics) and motion (mechanics). They even questioned Aristotle's ideas about how things move.

For several centuries, Islamic science thrived across a large area, from the Mediterranean Sea to further east. Many different schools, hospitals, and observatories supported this growth.

Contents

- A Look Back: History of Islamic Science

- Amazing Discoveries in Science

- Alchemy and Chemistry: Early Experiments

- Astronomy and Cosmology: Stargazing and Maps

- Botany and Agronomy: Plants and Farming

- Geography and Cartography: Mapping the World

- Mathematics: Numbers and Equations

- Medicine: Healing and Health

- Optics and Ophthalmology: The Science of Light and Eyes

- Pharmacology: The Art of Making Medicines

- Physics: How Things Move

- Zoology: The Study of Animals

- Why Islamic Science Was Important

- See also

A Look Back: History of Islamic Science

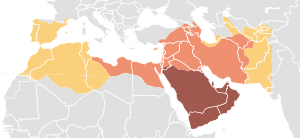

The Islamic era began in 622 CE. Over a short time, Islamic armies expanded across Arabia, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. They also took over lands from the Persian and Byzantine Empires. Within a hundred years, Islam reached as far as present-day Portugal in the west and Central Asia in the east.

The Islamic Golden Age (around 786 to 1258) happened during the Abbasid Caliphate. This was a time of stable governments and busy trade. Important religious and cultural books were translated into Arabic and sometimes Persian. Islamic culture blended ideas from Greek, Indian, Assyrian, and Persian traditions.

A new civilization grew, based on Islam. This led to a period of great learning and new ideas. Cities grew quickly, and the population increased. The Arab Agricultural Revolution brought new crops and better farming methods, like advanced irrigation. This helped feed more people and allowed culture and science to flourish.

Starting in the 800s, scholars like Al-Kindi translated knowledge from India, Assyria, Persia, and Ancient Greece. This included the works of Aristotle. These translations helped scientists across the Islamic world make new discoveries.

Islamic science continued even after Christian armies began to retake parts of Spain. Work still went on in eastern centers like Persia. After Spain was fully retaken in 1492, the Islamic world faced some economic and cultural challenges. However, scientific and artistic work continued under later empires like the Ottoman Empire and the Safavid Empire.

Amazing Discoveries in Science

Medieval Islamic scientists explored many different areas. The most important were mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. Other key fields included physics, chemistry, eye care, and map-making.

Alchemy and Chemistry: Early Experiments

The early Islamic period was important for setting up the basic ideas in alchemy and chemistry. One key idea was the sulfur-mercury theory of metals. This theory, found in texts from the 800s, suggested that all metals were made of sulfur and mercury. It was believed for centuries!

Writings linked to Jabir ibn Hayyan (around 850–950) and Abu Bakr al-Razi (around 865–925) gave the first organized ways to classify chemical substances. Alchemists also tried to create new substances. Jabir described how to make ammonium chloride from natural materials. Al-Razi experimented with heating different salts. These experiments later helped in discovering important mineral acids in the 1200s.

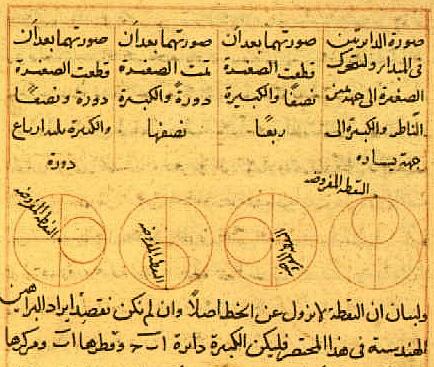

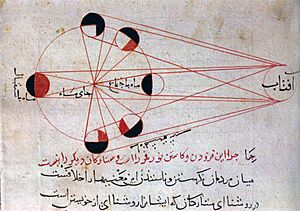

Astronomy and Cosmology: Stargazing and Maps

Astronomy became a very important science in the Islamic world. Astronomers wanted to understand the universe. They also used their knowledge for practical things. For example, they used astronomy to find the Qibla, the direction for prayer. They also used astrology to predict events or choose good times for actions.

Al-Battani (850–922) accurately figured out the length of the solar year. His work helped create the Tables of Toledo, which astronomers used to predict the movements of the sun, moon, and planets. Even Copernicus, a famous European astronomer, used some of Al-Battani's tables much later.

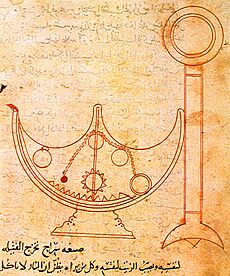

Al-Zarqali (1028–1087) made a much better astrolabe, a tool used to measure the positions of stars and planets. He also built a water clock in Toledo. He discovered that the Sun's highest point in the sky moves slowly, and he estimated how fast it moved.

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274) improved on Ptolemy's old model of the sky. He was given an observatory and learned from Chinese methods. He also developed trigonometry as its own field of study. He created the most accurate astronomical tables of his time.

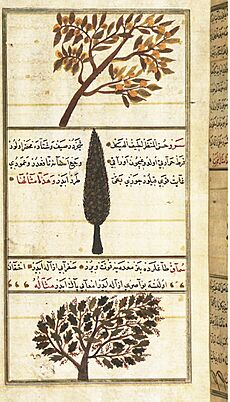

Botany and Agronomy: Plants and Farming

Scientists also carefully studied plants. This work was very helpful for the growth of pharmacology (the study of drugs) across the Islamic world.

Al-Dinawari (815–896) made botany popular with his six-volume Kitab al-Nabat (Book of Plants). Only parts of it survive, but it described hundreds of plants in alphabetical order. He also explained how plants grow, flower, and produce fruit.

Zakariya al-Qazwini (1203–1283) wrote an encyclopedia called ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt (The Wonders of Creation). It included both real plant descriptions and some imaginative stories.

The use and growing of plants were also well-documented. Muhammad bin Ibrāhīm Ibn Bassāl of Toledo wrote Dīwān al-filāha (The Court of Agriculture) in the 1000s. Ibn al-'Awwam al-Ishbīlī of Seville wrote Kitāb al-Filāha (Treatise on Agriculture) in the 1100s. Ibn Bassāl traveled widely, bringing back detailed knowledge of agronomy (the science of soil management and crop production). His book described over 180 plants and how to grow and care for them.

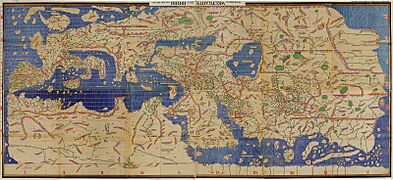

Geography and Cartography: Mapping the World

The spread of Islam led to a huge increase in trade and travel. People traveled by land and sea to places like Southeast Asia, China, Africa, Scandinavia, and even Iceland. Geographers worked to create more and more accurate maps of the known world.

Abu Zayd al-Balkhi (850–934) started a school of map-making in Baghdad. He wrote an atlas called Figures of the Regions.

Al-Biruni (973–1048) measured the Earth's radius using a new method. He did this by observing the height of a mountain in what is now Pakistan.

Al-Idrisi (1100–1166) drew a world map for King Roger II of Sicily. He also wrote the Tabula Rogeriana (Book of Roger). This book described the people, climates, resources, and industries of the entire known world at that time.

The Ottoman admiral Piri Reis (around 1470–1553) made a map of the New World and West Africa in 1513. He used maps from Greece, Portugal, Muslim sources, and possibly even one by Christopher Columbus.

-

A modern copy of al-Idrisi's 1154 Tabula Rogeriana, shown upside-down (north is at the top in this image).

Mathematics: Numbers and Equations

Islamic mathematicians collected, organized, and improved mathematical ideas from ancient Egypt, Greece, India, Mesopotamia, and Persia. Then, they made their own new discoveries. Islamic mathematics included algebra, geometry, and arithmetic.

Algebra was mostly used for fun puzzles back then, with few practical uses. Geometry was studied at different levels. Some texts had practical rules for surveying land. Deeper geometry was needed to understand astronomy and optics.

Early in the Abbasid Caliphate, around 762, scientists learned math from Persian astronomy. Indian astronomers were also invited to the court, sharing their basic trigonometry techniques. Ancient Greek works like Ptolemy's Almagest and Euclid's Elements were translated into Arabic. By the late 800s, Islamic mathematicians were already adding to complex Greek geometry. Islamic math reached its peak in the eastern Islamic world between the 900s and 1100s. Most medieval Islamic mathematicians wrote in Arabic, but some wrote in Persian.

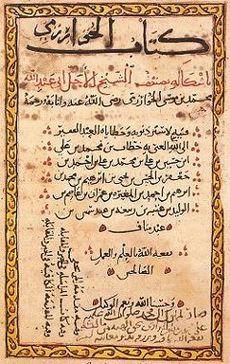

Al-Khwarizmi (700s–800s) was key in adopting the Hindu–Arabic numeral system (the numbers we use today). He also developed algebra and showed how to simplify equations. He was the first to treat algebra as its own subject. He also gave the first organized way to solve linear and quadratic equations.

Ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (801–873) worked on secret codes for the Abbasid Caliphate. He gave the first known explanation of how to break codes using frequency analysis.

Avicenna (around 980–1037) contributed to math techniques like casting out nines. Thābit ibn Qurra (835–901) solved a chessboard problem using a type of math series.

Al-Farabi (around 870–950) tried to explain the repeating patterns seen in Islamic art using geometry. Omar Khayyam (1048–1131), also known as a poet, calculated the length of the year very accurately. He also found geometric ways to solve all 13 types of cubic equations. Jamshīd al-Kāshī (around 1380–1429) is known for several trigonometry rules, including the law of cosines. He is also credited with inventing decimal fractions and a method to calculate roots. He calculated π (pi) with amazing accuracy.

Around the 600s, Islamic scholars adopted the Hindu–Arabic numeral system. They wrote books explaining how to use "Indian numbers." A special Western Arabic version of these numbers appeared around the 900s in North Africa and Spain. These are the direct ancestors of the Arabic numerals used worldwide today.

Medicine: Healing and Health

Islamic society cared deeply about medicine, following a religious teaching to stay healthy. Doctors learned from the knowledge and traditions of ancient Greece, Rome, Syria, Persia, and India. This included ideas from Hippocrates (like the theory of the four humours) and Galen.

Al-Razi (around 865–925) was the first to identify smallpox and measles. He also realized that fever is part of the body's defense. He wrote a huge 23-volume book combining Chinese, Indian, Persian, Syriac, and Greek medicine. Al-Razi even questioned Galen's ideas on how the four humours control body processes. He argued that bloodletting (a common treatment then) was effective.

Al-Zahrawi (936–1013) was a surgeon. His most important book, al-Tasrif (Medical Knowledge), has 30 volumes. It talks about medical symptoms, treatments, and drugs. The last volume, on surgery, describes surgical tools and new procedures.

Avicenna (around 980–1037) wrote a major medical textbook called The Canon of Medicine. This book was used for centuries. Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288) wrote an important medical book that largely replaced Avicenna's Canon in the Islamic world. He wrote comments on Galen's and Avicenna's works. In one of these, found in 1924, he described how blood circulates through the lungs, known as pulmonary circulation.

Optics and Ophthalmology: The Science of Light and Eyes

The study of optics (light) grew quickly during this time. By the 800s, there were books on how the eye works, how light travels, and how mirrors reflect light.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873) wrote Ten Treatises on the Eye. This book was very important in the Western world until the 1600s.

Abbas ibn Firnas (810–887) developed lenses to magnify things and improve vision.

Ibn Sahl (around 940–1000) discovered the law of light bending, known as Snell's law. He used this law to create the first Aspheric lenses, which could focus light perfectly without distortions.

In the 1000s, Ibn al-Haytham (also known as Alhazen, 965–1040) disagreed with older Greek ideas about vision. The Greeks thought either that objects sent their "form" into the eye, or that the eye sent out rays to see. Al-Haytham, in his Book of Optics, suggested that vision happens when light rays form a cone with its point at the center of the eye. He said that light reflects from different surfaces in different ways, making objects look different. He also argued that the math of reflection and refraction (light bending) must match the eye's anatomy. He was also an early supporter of the scientific method. He believed that ideas must be proven by experiments that can be repeated or by mathematical proof. This was five centuries before Renaissance scientists emphasized it.

Pharmacology: The Art of Making Medicines

New ideas in botany and chemistry in the Islamic world led to big steps forward in pharmacology (the study of drugs and medicines).

Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi (Rhazes) (865–915) encouraged using chemical compounds in medicine. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (Abulcasis) (936–1013) was a pioneer in preparing medicines using methods like sublimation and distillation. His book Liber servitoris gave instructions for preparing simple ingredients that were then mixed into complex drugs.

Sabur Ibn Sahl (died 869) was the first doctor to describe many different drugs and remedies for illnesses. Al-Muwaffaq, in the 900s, wrote The foundations of the true properties of Remedies. He described chemicals like arsenious oxide and silicic acid. He also told the difference between sodium carbonate and potassium carbonate. He warned about the poisonous nature of copper and lead compounds.

Al-Biruni (973–1050) wrote Kitab al-Saydalah (The Book of Drugs). It described the properties of drugs, the role of pharmacy, and what a pharmacist should do. Ibn Sina described 700 drug preparations, their properties, how they work, and when to use them. He dedicated a whole volume to simple ingredients in The Canon of Medicine.

Works by Masawaih al-Mardini (around 925–1015) and Ibn al-Wafid (1008–1074) were printed many times in Latin in Europe. Ibn al-Baytar (1197–1248), in his Al-Jami fi al-Tibb, described a thousand simple ingredients and drugs. He based this on plants he collected along the coast between Syria and Spain. This was more plants than even the classical Greek writer Dioscorides had covered. Islamic doctors like Ibn Sina also described clinical trials. These were experiments to figure out if medical drugs and substances actually worked.

Physics: How Things Move

Besides optics and astronomy, physicists in this period studied mechanics. This included statics (objects at rest), dynamics (objects in motion), and kinematics (describing motion).

In the 500s, John Philoponus disagreed with Aristotle's idea of motion. He argued that an object moves because it gets a push or "inclination" to move. In the 1000s, Ibn Sina had a similar idea. He said a moving object has a "force" that slowly goes away due to things like air resistance. Ibn Sina called this "inclination" (mayl). He believed an object keeps moving as long as this mayl lasts. He also said that an object in a vacuum would never stop unless something acted on it. This idea is very similar to Newton's first law of motion about inertia. This non-Aristotelian idea was later called "impetus" by Jean Buridan in the 1200s, who was likely influenced by Ibn Sina's The Book of Healing.

In his book Shadows, Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī (973–1048) described how uneven motion happens because of acceleration. Ibn Sina's theory of mayl tried to connect the speed and weight of a moving object, which was an early step towards the idea of momentum. Aristotle's theory said a constant force makes an object move at a constant speed. Abu'l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī (around 1080 – 1164/5) disagreed. He argued that speed and acceleration are different. He said that force is linked to acceleration, not to speed.

The Banu Musa brothers (early 800s) invented automated devices. They described these in their Book of Ingenious Devices. Other scientists like al-Jazari also made advances in mechanical devices.

Zoology: The Study of Animals

Many important classical Greek works, including those by Aristotle, were translated into Syriac, then Arabic, and later Latin. Aristotle's zoology (study of animals) was the main source of knowledge in this field for 2,000 years.

The Kitāb al-Hayawān (Book of Animals) is an Arabic translation from the 800s. It includes parts of Aristotle's works like History of Animals, On the Parts of Animals, and Generation of Animals.

Al-Kindī (died 850) mentioned this book, and Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā) wrote comments on it in his The Book of Healing. Other scholars like Avempace (Ibn Bājja) and Averroes (Ibn Rushd) also commented on and discussed Aristotle's works on animals.

Why Islamic Science Was Important

Muslim scientists helped create the basis for experimental science. They contributed to the scientific method by using empirical (based on observation) and quantitative (using measurements) approaches to scientific study.

More generally, Islamic science was successful because it thrived for centuries. It grew in many different places, from observatories and libraries to schools (madrasas), hospitals, and royal courts. This happened both during the peak of the Islamic Golden Age and for several centuries afterward. While it didn't lead to a "scientific revolution" like the one in Early modern Europe, it was a very successful period of learning and innovation in its own right.

See also

- Continuity thesis

- Indian influence on Islamic science

- History of scientific method

- History of Islamic economics

- Islamic philosophy

- Islamic attitudes towards science

- Scholasticism

- Timeline of science and engineering in the Muslim world