Mustang facts for kids

Mustang adopted from the Bureau of Land Management

|

|

| Distinguishing features | Small, compact, good bone, very hardy |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | North America |

| Horse (Equus ferus caballus) | |

A mustang is a free-roaming horse found in the Western United States. These horses are descendants of horses first brought to the Americas by the Spanish. People often call mustangs "wild horses." However, because their ancestors were once domesticated (tamed by humans), mustangs are actually feral horses. This means they were once tame but now live in the wild.

The first mustangs were Colonial Spanish horses. Over time, many other types of horses mixed with them. This means modern mustangs can look very different from each other. Some free-roaming horses still look a lot like the original Spanish horses. These are usually found in very isolated areas.

In 1971, the United States Congress officially recognized that "wild free-roaming horses and burros are living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West." They said these animals add to the diversity of life in the country and make people's lives better. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) now manages and protects these free-roaming horse populations.

There is some disagreement about how mustangs share land and resources with livestock raised by ranching businesses. There are also debates about how the BLM manages the number of mustangs. The most common way to control their population is to gather extra horses. These horses are then offered for adoption to people who want them. But not enough people adopt them. So, many mustangs end up in temporary or long-term holding areas. There are worries that these horses might be sold for purposes they shouldn't be. People also debate if mustangs are a native species (originally from here) or an invasive species (introduced and causing problems) in the lands where they live.

Contents

Understanding the Name "Mustang"

Although free-roaming mustangs are called "wild" horses, they come from horses that were once tamed.

Where the Word "Mustang" Comes From

The English word mustang probably came from two similar Spanish words: mestengo and mesteño. These words meant 'strayer' or 'wild, having no master'. The word mostrenco was used since the 1200s, and mesteño appeared in the late 1400s.

Mesteño first referred to animals whose owners were unknown. These animals were given out by a powerful group of merino sheep ranchers in medieval Spain called the Mesta. The Mesta's name came from a Latin word meaning 'mixed'. This referred to the animals being commonly owned by many people. In Spanish, mustangs are called mesteños. By 1936, the English word 'mustang' was even borrowed back into Spanish as mustango.

Who Were the Mustangers?

"Mustangers" were cowboys (called vaqueros in Spanish). They caught, trained, and moved free-ranging horses to markets. This happened in Spanish and later American lands, including what is now northern Mexico, Texas, New Mexico, and California. They caught horses that roamed the Great Plains, the San Joaquin Valley of California, and later the Great Basin. This practice lasted from the 1700s to the early 1900s.

Mustang Characteristics and Family History

The first mustangs were Colonial Spanish horses. But many other types of horses have contributed to modern mustangs. This means they can have different looks, or phenotypes. Mustangs of all body types are known for being surefooted (good at walking on tricky ground) and having good endurance. They can be any color.

Most mustangs managed by the Bureau of Land Management are light riding horses. However, some horses with draft horse (heavy work horse) features also exist. These are usually kept separate from other mustangs in specific areas. Some herds show signs of having Thoroughbred or other light racehorse types in their family history. This mixing also helped create the American Quarter Horse.

Different Mustang Herds Today

Today's free-roaming mustang herds have different groups that are genetically separate. This means they have unique traits that come from specific herds. For example, some herds in Idaho have horses known to be descendants of Thoroughbred and Quarter Horse stallions that were released with wild herds. Herds in central Nevada produce Curly Horses, which have curly coats. Other herds, like some in Wyoming, have traits similar to gaited horse breeds (horses that move in special ways).

Scientists have studied the genes of many herds. They found that the Pryor Mountain Mustang has Spanish ancestors. Horses in other areas also show Spanish horse traits. These include dun coloration (a specific coat color) and primitive markings (like stripes on legs). Genetic studies of other herds show a mix of Spanish, gaited horse, draft horse, and pony influences.

Size and Quality

Mustangs vary in height across the West. Most are small, usually 14 to 15 hands tall. They are rarely taller than 16 hands, even those with draft or Thoroughbred ancestors.

Some people who breed domestic horses think mustangs are inbred and not as good quality. However, mustang supporters say the animals are only small because of their tough living conditions. They argue that natural selection (where nature chooses the strongest traits) has removed traits that lead to weakness.

The American Mustang Association, which no longer exists, created a standard for mustangs that look like early Spanish horses. These horses have well-proportioned bodies with a clean, refined head, a wide forehead, and a small muzzle. Their face can be straight or slightly curved. They have moderate Withers (the highest part of the back at the base of the neck) and a long, sloping shoulder. A very short back, deep chest, and muscular loins are also desired. The rump is rounded, and the tail is set low. Their legs should be straight and strong. Their hooves are round and dense. Dun color and primitive markings are common in Spanish-type horses.

Mustang History

Early Horses in the Americas (1493–1600)

Modern horses first came to the Americas with the conquistadors (Spanish explorers and conquerors). This started with Christopher Columbus on his second voyage in 1493. Horses arrived on the mainland with Hernán Cortés in 1519. By 1525, Cortés had brought enough horses to start horse breeding in Mexico.

It was once thought that horse populations north of Mexico began in the mid-1500s with expeditions like those of Narváez or Francisco Vázquez de Coronado. However, this idea has been disproven. A large enough horse population to survive on its own began in what is now the southwestern United States in 1598. This was when Juan de Oñate founded Santa Fe de Nuevo México. He started with 75 horses and grew his herd to 800. From there, the horse population grew very quickly.

The Spanish also brought horses to Florida in the 1500s. But the Choctaw and Chickasaw horses of the southeastern United States are thought to be descendants of western mustangs that moved east. So, the Spanish horses in Florida did not affect the mustang population.

Horses Spread Across the Land (17th and 18th Centuries)

Native American people quickly started using horses in their daily lives. Horses became a main way to travel. They replaced dogs as pack animals (animals that carry things). Horses also changed Native cultures in terms of warfare, trade, and even food. Being able to chase bison on horseback allowed some people to stop farming and focus on hunting.

Santa Fe became a big trading center in the 1600s. Spanish laws did not allow Native Americans to ride horses. But the Spanish used Native people as servants, and some cared for livestock. This is how they learned horse-handling skills. Oñate's settlers also lost many horses. Some wandered off because the Spanish did not keep them in fenced areas. Native people in the area captured some of these estrays (stray animals). Other horses were traded by Oñate's settlers for food or other goods. At first, Native people just ate the horses they got. But as individuals who knew how to handle horses escaped Spanish control, sometimes with a few trained horses, local tribes began using horses for riding and carrying things. By 1659, settlements reported being raided for horses. In the 1660s, the "Apache" traded human captives for horses. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 also led to many horses falling into Native people's hands. This was the largest single event of horses spreading in history.

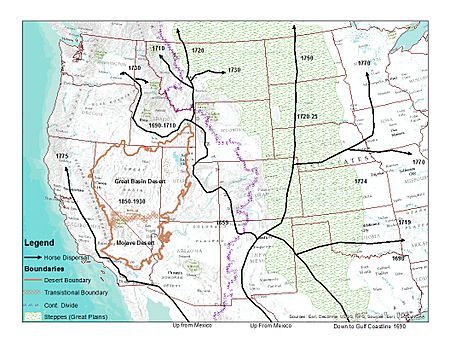

From the Pueblo people, horses were traded to the Apache, Navajo, and Utes. The Comanche got horses and gave them to the Shoshone. The Eastern Shoshone and Southern Utes became traders. They spread horses and horse culture from New Mexico to the northern plains. West of the Continental Divide, horses spread north quickly along the western Rocky Mountains. They avoided desert areas like the Great Basin. Horses reached what is now southern Idaho by 1690. The Northern Shoshone people in the Snake River valley had horses by 1700. By 1730, horses reached the Columbia Basin and were east of the Continental Divide in the northern Great Plains. The Blackfeet people of Alberta had horses by 1750. The Nez Perce people became expert horse breeders. They developed one of the first truly American breeds, the Appaloosa. Most other tribes did not do much selective breeding. However, they looked for good horses and quickly removed those with bad traits. By 1769, most Plains Indians had horses.

During this time, Spanish missions were also a source of stray and stolen livestock. This was especially true in what is now Texas and California. The Spanish brought horses to California for their missions and ranches. Permanent settlements were set up there in 1769. Horse numbers grew fast, with 24,000 horses reported by 1800. By 1805, there were so many horses in California that people started killing unwanted animals to reduce overpopulation. However, because of mountains and deserts, the California horse population did not greatly affect horse numbers elsewhere at that time. Horses in California were described as being of "exceptional quality."

In the upper Mississippi basin and Great Lakes regions, the French were another source of horses. Trading horses with Native people was forbidden. But some individuals did illegal trading. As early as 1675, the Illinois people had horses. Animals called "Canadian," "French," or "Norman" were found in the Great Lakes region. A 1782 count at Fort Detroit listed over 1000 animals. By 1770, Spanish horses were in that area. There was a clear zone from Ontario and Saskatchewan to St. Louis where Canadian-type horses mixed with mustangs of Spanish ancestry. French-Canadian horses were also allowed to roam freely. They moved west, especially influencing horse herds in the northern plains.

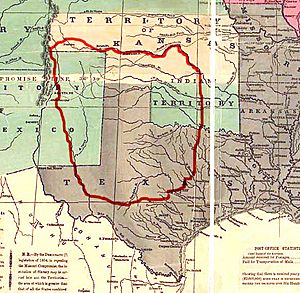

Although horses came from Mexico to Texas as early as 1542, a stable population did not exist until 1686. That's when Alonso de León's expedition arrived with 700 horses. From there, later groups brought thousands more. They sometimes deliberately left horses and cattle to roam free. Others simply strayed. By 1787, these animals had multiplied so much that a roundup gathered nearly 8,000 "free-roaming mustangs and cattle." West-central Texas, between the Rio Grande and Palo Duro Canyon, was said to have the most concentrated population of feral horses in the Americas. Across the West, horses escaped human control and formed wild herds. By the late 1700s, the largest numbers were in what are now Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, and New Mexico.

Mustangs in the 1800s

One of the first times Americans wrote about mustangs was in 1808. Zebulon Pike mentioned seeing herds of "mustangs or wild horses." In 1821, Stephen F. Austin wrote in his journal that he had seen about 150 mustangs.

No one knows exactly when the mustang population was at its highest or how many there were. No full count of wild horses was done until the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971. Any earlier numbers are just guesses. Some sources say "millions" of mustangs once roamed western North America. In 1959, a geographer named Tom L. McKnight thought the population peaked in the late 1700s or early 1800s. He guessed there were "between two and five million." Historian J. Frank Dobie thought the population peaked around 1848, after the Mexican–American War. He guessed: "My own guess is that at no time were there more than a million mustangs in Texas and no more than a million others scattered over the remainder of the West."

In 1839, the number of mustangs in Texas grew. This was because Mexican settlers left animals behind when they were told to leave the Nueces Strip. Ulysses S. Grant, in his memoir, remembered seeing a huge herd in 1846. It was between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande in Texas. He wrote: "As far as the eye could reach to our right, the herd extended. To the left, it extended equally. There was no estimating the number of animals in it." When this area became part of the U.S. in 1848, these horses were rounded up. This almost completely removed mustangs from that area by 1860.

Farther west, the first known sighting of a free-roaming horse in the Great Basin was by John Bidwell in 1841. Although John C. Frémont saw thousands of horses in California, he only mentioned horse tracks around Pyramid Lake in the Great Basin. The Native people he met there did not have horses. In 1861, another group saw seven free-roaming horses near the Stillwater Range. Most free-roaming horse herds in Nevada's interior were formed later in the 1800s from settlers' escaped horses.

Mustangs in the 20th Century and Today

Early 1900s to Mid-Century

In the early 1900s, thousands of free-roaming horses were rounded up. They were used in the Spanish–American War and World War I.

By 1920, Bob Brislawn, who worked for the U.S. government, realized that the original mustangs were disappearing. He worked to save them and started the Spanish Mustang Registry. In 1934, J. Frank Dobie said there were only "a few wild [feral] horses in Nevada, Wyoming and other Western states." He also said that "only a trace of Spanish blood is left in most of them." Other sources agree that by then, only small groups of mustangs still looked like the Colonial Spanish Horse type.

By 1930, most free-roaming horses were found west of the Continental Divide. Their population was estimated to be between 50,000 and 150,000. They were almost entirely on public lands managed by the General Land Office (GLO) and National Forest rangelands in the 11 Western States. In 1934, the Taylor Grazing Act created the United States Grazing Service to manage livestock grazing on public lands. In 1946, the GLO and Grazing Service combined to form the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The BLM, along with the Forest Service, was committed to removing wild horses from the lands they managed.

Protecting Mustangs

By the 1950s, the mustang population dropped to about 25,000 horses. People were concerned about how horses were being captured. Some methods included hunting from airplanes and poisoning water holes. These abuses led to the first federal law protecting free-roaming horses in 1959. This law, known as the "Wild Horse Annie Act," stopped the use of motor vehicles for capturing free-roaming horses and burros. Protection increased even more with the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 (WFRHABA).

The Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 protected certain existing herds of horses and burros. It told the BLM to protect and manage free-roaming herds on its lands. The U.S. Forest Service got similar power on National Forest lands. A few free-ranging horses are also managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Park Service. But most are not under the 1971 Act. A count done with the Act's passage found about 17,300 horses (and 25,300 total horses and burros) on BLM lands. There were 2,039 on National Forests.

Mustangs Today

The BLM has set up Herd Management Areas (HMAs). These are places where horses will live as free-roaming populations. The BLM has set "Appropriate Management Levels" (AML) for each HMA, totaling 26,000 horses across all areas. However, in August 2017, the actual mustang population on the range was estimated to be over 72,000 horses. More than half of all free-roaming mustangs in North America are in Nevada. Nevada even features horses on its State Quarter. Other large populations are in California, Oregon, Utah, Montana, and Wyoming. Another 45,000 horses are in holding facilities.

Prehistoric Horses in North America

The horse family, called Equidae, first appeared in North America 55 million years ago. By the end of the Late Pleistocene (a long time ago), two types of horses lived in North America. One was the "caballine" or "stout-legged horse," which is the ancestor of the modern horse. The other was the "stilt-legged horse." Recent studies of ancient DNA show that the North American caballine horses included the ancestor of the modern horse. At the end of the Last Glacial Period (Ice Age), the "stilt-legged horses" died out. The "caballine" horses disappeared from the Americas. This might have been due to changing climate and the impact of early human hunters. So, before Christopher Columbus came, the last physical evidence of horses in the Americas dates back about 10,500 to 7,600 years ago.

Modern Debates About Mustangs

Because of the horse's long history, there's a debate about what role mustangs play in the environment. There's also discussion about how important they are compared to other uses of public lands, especially for livestock.

Some people who support mustangs on public lands say that even though mustangs are not native, they are a "culturally significant" part of the American West. They agree that some population control is needed. Another idea is that mustangs returned to an ecological niche (a role in the environment) that was empty when horses died out in North America. This idea says horses are a reintroduced native species and should be called "wild" instead of "feral." They should be managed like other wildlife. This "native species" argument focuses on whether the horses that disappeared 10,000 years ago are closely related to modern horses.

The Wildlife Society sees mustangs as an introduced species. They say: "Since native North American horses went extinct, the western United States has become more arid... changing the ecosystem and the roles horses and burros play." They also believe mustangs take resources and attention away from truly native species. A 2013 report by the National Research Council disagreed with the idea of horses being a reintroduced native species. It said that "the complex of animals and vegetation has changed since horses were extirpated from North America." It also stated that whether horses are native or not isn't the main issue. Instead, the debate is about how much priority the BLM gives to free-ranging horses and burros on federal lands compared to other uses.

Mustang supporters want the BLM to give mustangs higher priority. They argue that too little food is given to mustangs compared to cattle and sheep. Ranchers and others in the livestock industry want a lower priority for mustangs. They argue that their businesses and rural economies depend on public land for their livestock.

The debate about how much mustangs and cattle compete for food is complex. Horses have evolved to live in places with poor quality plants. Supporters say that most mustang herds live in dry areas that cattle cannot fully use because there isn't enough water. Mustangs can travel long distances to find food and water. Supporters say horses travel 5–10 times farther than cattle to find food, even in hard-to-reach areas. Also, horses are "hindgut fermenters." This means they digest food in their cecum rather than a multi-chambered stomach. While this means they get less energy from the same amount of food, they can digest food faster. They make up for it by eating more. So, by eating larger amounts, horses can get enough nutrition from poorer food than ruminants like cattle. This means they can survive in areas where cattle would starve.

However, the BLM counts horses as eating the same amount of food as a cow–calf pair (1.0 animal unit (AUM)). But studies show that horses probably eat closer to 1.5 AUM. Modern rangeland management also suggests removing all livestock during the growing season. This helps plants grow back as much as possible. Grazing all year by any non-native ungulate (hoofed animal) will damage the land. This is especially true for horses. Their incisors (front teeth) allow them to graze plants very close to the ground, which makes it harder for the plants to recover.

Managing and Adopting Mustangs

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) was given the job by Congress to protect, manage, and control free-roaming horses and burros. This is under the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971. The goal is to make sure healthy herds live on healthy rangelands, as stated in the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act. It's hard to manage them because mustang herd sizes can grow very quickly, possibly by over 20% each year. If not managed, the population can become too large for the available food, leading to starvation.

Controlling Mustang Populations

In modern times, few predators can hunt healthy adult mustangs. Most predators that could limit the growth of wild mustang herds do not live in the same areas as most modern wild herds. While wolves and mountain lions are known to hunt horses, they usually don't control the population much. Wolves were rare in the Great Basin, where most mustangs live, and are not there now. While wolves hunt wild horses in Canada, there's no record of them hunting free-roaming horses in the United States. Mountain lions do hunt wild horses in the U.S., but only in small areas and in small numbers, mostly hunting foals (baby horses).

One of the BLM's main jobs under the 1971 law is to keep the number of wild horses and burros within the "Appropriate Management Level" (AML). This is for public rangelands managed by the federal government. To control the population, the BLM uses a capture program. There are no specific rules for how to round up mustangs. Most methods are very stressful for the animals, and can even be deadly. The BLM allows the use of trucks, ATVs, helicopters, and firearms to chase horses into holding pens or "traps." These methods have often caused extreme tiredness, serious injuries, or even death to the horses. "Bait" traps are another common way to gather mustangs. Hay or water is left in a hidden pen, and different trigger systems close gates behind the horses. Another, less harmful method uses a tamed horse, called a "Judas horse." This horse is trained to lead wild horses into a pen or corral. Once the mustangs are near the holding pen, the Judas horse is released. Its job is to go to the front of the herd and lead them into the confined area.

Adoption and Sales

Since 1978, captured horses have been offered for adoption. Individuals or groups can adopt them if they are willing and able to provide good, long-term care after paying an adoption fee, which is usually $125. Adopted horses are still protected by the Act for one year after adoption. After that year, the adopter can get full ownership of the horse. Horses that could not be adopted were supposed to be humanely put down. Instead of doing this, the BLM started keeping them in "long term holding" facilities. This is a very expensive choice, costing taxpayers up to $50,000 per horse over its lifetime.

On December 8, 2004, a change was added to the Wild and Free Roaming Horse and Burro Act by former Senator Conrad Burns. This change allowed the unlimited sale of captured horses that are "more than 10 years of age" or that were "offered unsuccessfully for adoption at least three times." Since 1978, the Act had specific language stopping the BLM from selling horses to people who would take them to be processed for other purposes. But the Burns Amendment removed that language. To prevent horses from being sold for those purposes, the BLM has put in place rules that limit sales. Buyers must also promise they will not sell the horses for such uses. In 2017, the Trump administration started asking Congress to remove rules that stopped them from putting down or selling extra horses.

Despite efforts to increase adoptions, like the Extreme Mustang Makeover (a competition where trainers have 100 days to gentle and train mustangs for auction), not enough homes are found for the extra horses. In 2017, 10,000 foals were expected to be born in the wild, but only 2,500 horses were expected to be adopted. Other ways to control the population in the wild, besides roundups, include fertility control (like injections or spaying mares), removing weaker animals, and letting nature control the numbers.

Mustang Identification

Captured horses are freeze branded on the left side of their neck by the BLM. They use a special system of angles and symbols that cannot be changed. The brands start with a symbol for the registering organization (the U.S. Government). Then, two numbers show the horse's birth year, followed by its individual registration number. Captured horses kept in sanctuaries are also marked on their left hip with four-inch-high numbers. These numbers are the last four digits of the freeze brand on their neck.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Mustang (caballo) para niños

In Spanish: Mustang (caballo) para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |