Afro–Puerto Ricans facts for kids

| AfroPuertorriqueños • Afroborincanos | |

|---|---|

Afro–Puerto Rican women in Bomba dance wear

|

|

| Total population | |

| 435,676-1,000,000 (32.8%) (Includes Afro–Puerto Ricans living outside of Puerto Rico) |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Puerto Rico (more heavily concentrated in coastal Northeast regions of the island) |

|

| Languages | |

|

|

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Catholicism; Protestantism; Rastafari and other Afro-diasporic religion (mainly Santería) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Afro-Latin American and Afro-Caribbean ethnic groups |

Afro–Puerto Ricans are people from Puerto Rico who have mostly African ancestors. Many also identify as Black. Most Puerto Ricans today have at least some African heritage. The story of Afro–Puerto Ricans began with free African men. They were called libertos. These men came with the Spanish Conquistadors, who were explorers and conquerors.

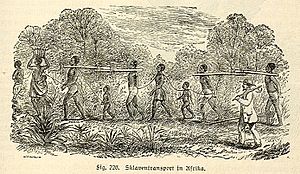

The Spanish first enslaved the Taíno people. They were the native people of the island. Many Taíno died from new diseases and harsh treatment. The Spanish government needed more workers. So, they started bringing enslaved people from West Africa. These people were part of the Atlantic slave trade. They came from many different cultures across Africa.

When the gold mines in Puerto Rico ran out, Spain didn't see the island as important. Its main ports were used to support navy ships. Spain encouraged free people of color from other Caribbean islands to move to Puerto Rico. This helped grow the island's population. In 1789, a Spanish rule allowed enslaved people to earn or buy their freedom. But this didn't help much at first. More sugar cane farms meant more demand for workers. So, more enslaved people were brought in.

Over the years, there were many slave revolts. Enslaved people who were promised freedom joined a big uprising in 1868. This event was called the Grito de Lares. On March 22, 1873, slavery was officially ended in Puerto Rico. African people have greatly shaped Puerto Rican culture. Their influence is seen in music, art, language, and traditions.

Contents

First Africans Arrive in Puerto Rico

When Spanish explorers like Juan Ponce de León arrived in Puerto Rico, the native Taíno people welcomed them. The Taíno leader was Cacique Agüeybaná. He tried to keep peace between his people and the Spanish. In 1509, a free African man named Juan Garrido came to the island. He was a conquistador with Ponce de León. Garrido was born in West Africa and was the son of an African king. He helped explore Puerto Rico and look for gold. He also fought with Ponce de León against the Taíno and Carib people in 1511.

Another free African man was Pedro Mejías. He married a Taíno woman chief named Yuisa. She was baptized as Catholic to marry him. The town of Loíza, Puerto Rico is named after her.

The peace between the Spanish and Taíno didn't last. The Spanish enslaved the Taíno. They forced them to work in gold mines and build forts. Many Taíno died from diseases like smallpox. They had no natural protection against these new sicknesses.

A priest named Friar Bartolomé de las Casas was upset by how the Spanish treated the Taíno. In 1512, he spoke out against it. He fought for the Taínos' rights. But the Spanish colonists worried about losing their workers. They needed people for mines, forts, and sugar cane farms. So, Las Casas suggested bringing enslaved people from Africa instead. In 1517, the Spanish King allowed people to bring twelve enslaved Africans each. This started the African slave trade in their colonies.

Most enslaved Africans came from areas like present-day Gold Coast, Nigeria, and Dahomey. These areas were known as the Slave Coast. Many were Yorubas and Igbos from Nigeria. Others were Bantus from the Guineas. The number of enslaved people in Puerto Rico grew from 1,500 in 1530 to 15,000 by 1555. Enslaved people were branded on their foreheads with a hot iron. This showed they were brought in legally.

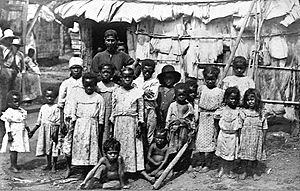

African enslaved people worked in gold mines or on farms. They grew ginger and sugar. They could live with their families in a small hut on their master's land. They also got a small plot to grow food. Enslaved Africans faced unfair treatment. They learned Spanish from their masters and taught it to their children. They also added African words to the "Puerto Rican Spanish" language. Many were forced to become Christian and were given Spanish last names.

In 1527, the first big slave rebellion happened in Puerto Rico. Some enslaved people escaped to the mountains. They lived there as maroons with surviving Taínos. Over the next centuries, there were more than twenty revolts.

By 1570, the gold mines were empty. Spain then focused on richer colonies like Mexico. Puerto Rico became a military base for passing ships. Growing crops like tobacco and sugar became important. As sugar demand grew, more enslaved people were needed for the hard work on sugar plantations. Spain even gave loans and tax breaks to plantation owners.

To get more workers, Spain offered freedom and land in 1664. This was for people of African descent from British and French colonies. Many of these free people had mixed African and European backgrounds. They helped support the military base in Puerto Rico. These freedmen adopted Spanish ways. Some joined the local army and fought against British attacks. Many still have non-Spanish last names today.

After 1784, Spain stopped branding enslaved people. They also offered ways for enslaved people to gain freedom:

- Masters could free enslaved people in a church or in front of a judge.

- Enslaved people could gain freedom by reporting crimes against the king or their master.

- If an enslaved person received part of their master's property in a will, they were freed. This sometimes happened for mixed-race children of masters.

- If an enslaved person was made a guardian for their master's children, they were freed.

- If enslaved parents had ten children, their whole family was freed.

Royal Decree of Graces of 1789

In 1789, the Spanish King made a new rule called the "Royal Decree of Graces." It changed how enslaved people were traded and freed. It allowed people to buy enslaved people and join the slave trade in the Caribbean. Later that year, a new slave code, called El Código Negro (The Black Code), was introduced.

Under "El Código Negro," an enslaved person could buy their freedom. They had to pay the price their master asked. Enslaved people could earn money in their free time. They worked as shoemakers, cleaned clothes, or sold food from their own small farms. They could pay for their freedom in parts. They could even pay half price for a newborn child's freedom before baptism. Many freed people started new communities. These areas became known as Cangrejos (Santurce), Carolina, Canóvanas, Loíza, and Luquillo. Some even became slave owners themselves.

Puerto Ricans born on the island wanted to join the Spanish army. In 1741, Spain created the Regimiento Fijo de Puerto Rico. Many former enslaved people, now freed, joined this army or the local militia. Afro–Puerto Ricans helped defeat the British in 1797 when they tried to invade the island.

Even with ways to gain freedom, the number of enslaved people more than doubled after 1790. This was because the sugar industry grew so much. Sugar farming was very hard work. Many enslaved people died on the sugar plantations.

The 1800s: Changes and Freedom

New Rules and Rebellions

| Year | White | Mixed | Free Blacks | Slaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1827 | 163 | 100 | 27 | 34 |

| 1834 | 189 | 101 | 25 | 42 |

| 1847 | 618 | 329 | 258 | 32 |

The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 encouraged people from Spain and other European countries to move to Cuba and Puerto Rico. This rule also promoted using enslaved labor to boost farming. New farmers from Europe used many enslaved people. They often treated them very harshly.

Enslaved people fought back. From the 1820s to 1868, there were many uprisings. The last one was the Grito de Lares. In 1821, an enslaved man named Marcos Xiorro planned a revolt against sugar plantation owners. Even though his plan was stopped, Xiorro became a legend among enslaved people.

In 1834, a census showed that 11% of Puerto Rico's population were enslaved. 35% were free people of color, and 54% were white. In the next ten years, the number of enslaved people grew a lot. This was because more were brought in for sugar plantations.

In 1836, newspapers like the Gaceta de Puerto Rico published names and descriptions of escaped enslaved people. If a Black person was caught and thought to be enslaved, their information was published.

Plantation owners became worried because there were so many enslaved people. They put limits on their movement. A Black Puerto Rican writer, Rose Clemente, said that until 1846, Black people on the island had to carry a notebook to move around. This was similar to the passbook system in apartheid South Africa.

After enslaved people in Haiti successfully rebelled against the French in 1803, Spain became afraid. They worried that Puerto Rico and Cuba, their last colonies, might do the same. The Spanish government then issued the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815. This was to bring European immigrants to the island. Spain thought these new immigrants would be more loyal. However, these immigrants often married local people. They also started to feel a strong connection to their new home.

In 1848, Governor Juan Prim created strict laws. These laws, called "El Bando contra La Raza Africana", controlled all Black Puerto Ricans, whether free or enslaved. This was because he feared revolts.

On September 23, 1868, enslaved people who were promised freedom joined a short revolt against Spain. It was called "El Grito de Lares." Many who took part were jailed or killed.

During this time, Puerto Rico had a unique way for people to change their racial status. Under laws like Regla del Sacar or Gracias al Sacar, a person with African ancestors could be considered legally white. They just had to prove they had white ancestors in their family for four generations. This was different from the "one-drop rule" in the United States. There, any known African ancestry meant a person was classified as Black.

Fighting for Freedom

In the mid-1800s, a group of people who wanted to end slavery formed in Puerto Rico. They were called abolitionists. Dr. Ramón Emeterio Betances and Segundo Ruiz Belvis were two important Puerto Rican abolitionists. They started a secret group called "The Secret Abolitionist Society." Their goal was to free enslaved children. They did this by paying for the children's freedom when they were baptized. This event was known as "aguas de libertad" (waters of liberty). It happened at the Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria Cathedral in Mayagüez. Betances would give money to the parents. They used it to buy their child's freedom from the master.

José Julián Acosta was also part of a Puerto Rican group that went to Madrid, Spain. There, Acosta argued for ending slavery in Puerto Rico. On November 19, 1872, Román Baldorioty de Castro and others also proposed ending slavery.

On March 22, 1873, the Spanish government approved the Moret Law. This law slowly ended slavery. It freed enslaved people over 60 years old. It also freed those owned by the state and children born to enslaved people after September 17, 1868.

The Moret Law created the Central Slave Registrar. This office collected information about enslaved people. This included their name, origin, where they lived, parents' names, age, and master's name. This information is very helpful for historians today.

Slavery Ends

On March 22, 1873, slavery was ended in Puerto Rico. But there was a catch. Enslaved people were not simply set free. They had to buy their own freedom. The price was set by their former masters. The law also said that former enslaved people had to work for three more years. They could work for their former masters, other people, or the government. This was to pay some money to their former owners.

Former enslaved people earned money in different ways. Some worked as shoemakers or cleaned clothes. Others sold food they grew on small plots of land. This was similar to sharecroppers in the southern United States after the American Civil War. The government created the Protector's Office. This office helped manage the change. It also paid any money still owed to former masters after the work contract ended.

Most freed people continued to work for their former masters. But now they were free and earned wages. If a freed person chose not to work for their former master, the Protector's Office would pay the master a part of the person's value.

Freed enslaved people became part of Puerto Rican society. Racism has existed in Puerto Rico. But it is often seen as less harsh than in other places. This might be for a few reasons:

- In the 700s, the Arab-Berber/African Moors conquered Spain. The first African enslaved people came to Spain with North African traders. By the 1200s, Christians took back Spain. Many Africans became free after becoming Christian. They lived alongside Spanish people. Spanish men often married African women. Spain's long history with people of color may have led to more open attitudes about race in the New World.

- The Catholic Church helped protect the dignity of African people in Puerto Rico. The church said every enslaved person must be baptized. It taught that masters and enslaved people were equal before God. Cruel punishment was seen as wrong.

- When gold mines ran out in 1570, many white Spanish settlers left Puerto Rico. They went to richer colonies like Mexico. Most people who stayed were African or mulattoes (of mixed race). By the time Spain reconnected with Puerto Rico, the island had many mixed-race people. The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 brought many European immigrants. This made the island seem "whiter" by the 1850s. But these new arrivals also married local islanders, adding to the mixed population.

Two Puerto Rican writers, Abelardo Díaz Alfaro and Luis Palés Matos, wrote about racism. Palés Matos created a type of poetry called Afro-Antillano.

Puerto Rico and the United States

The Treaty of Paris in 1898 ended the Spanish–American War. This meant Spain no longer controlled Puerto Rico. The island now belonged to the United States. With US control, Puerto Ricans had less say in their own government. This was different from the political freedom they had been working towards with Spain.

Afro–Puerto Ricans knew about the challenges and opportunities for Black people in the United States. The strict Jim Crow Laws in the US were very different from the growing Black culture of the Harlem Renaissance.

One important Afro–Puerto Rican politician was Dr. José Celso Barbosa (1857–1921). In 1899, he started the Puerto Rican Republican Party. He is known as the "Father of the Statehood for Puerto Rico" movement. Another important Afro–Puerto Rican was Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (1874–1938). He wanted Puerto Rico to be independent. He moved to New York City. There, he collected many old papers and items about Black Americans and the African diaspora. He is sometimes called the "Father of Black History" in the United States. A large research center in New York is named after him. He also created the term Afroborincano, meaning African-Puerto Rican.

Facing Unfair Treatment

After the United States Congress passed the Jones Act in 1917, Puerto Ricans became US citizens. As citizens, they could be drafted into the military during World War I. But the US armed forces were separated by race until after World War II. Afro–Puerto Ricans faced unfair treatment in the military and the US.

Black Puerto Ricans living in the US were put into all-Black units. Rafael Hernández and his brother Jesus, along with 16 other Puerto Ricans, joined a jazz band led by James Reese Europe. They were part of the 369th Infantry Regiment, an African-American unit. This unit became famous in World War I and was called "The Harlem Hell Fighters" by the Germans.

The US also separated military units in Puerto Rico. Pedro Albizu Campos (1891–1965), who later led the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, was a lieutenant. He started the "Home Guard" unit in Ponce. He was later assigned to the 375th Infantry Regiment, an all-Black Puerto Rican unit. This unit stayed in Puerto Rico and did not fight in the war. Albizu Campos later said that the unfair treatment he saw in the military shaped his political beliefs.

Afro–Puerto Ricans also faced unfair treatment in sports. Dark-skinned Puerto Ricans were not allowed to play Major League Baseball in the United States. In 1892, baseball created a "color line." This stopped African-American players and any dark-skinned player from any country from playing.

But Afro–Puerto Ricans kept playing baseball. In 1928, Emilio "Millito" Navarro went to New York City. He became the first Puerto Rican to play in the Negro leagues. He joined the Cuban Stars. Others followed, like Francisco Coimbre.

These players helped open the way for stars like Roberto Clemente and Orlando Cepeda. They played in the Major Leagues after the color line was broken in 1947 by Jackie Robinson. Clemente and Cepeda are now in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Cepeda's father, Pedro Cepeda, was a great player. But he could not play in the major leagues because of his skin color. He refused to play in the Negro leagues because he hated the unfair treatment in the US.

Black Puerto Ricans also competed in other international sports. In 1917, Nero Chen became the first Puerto Rican boxer to gain international fame. In the 1948 Summer Olympics in London, boxer Juan Evangelista Venegas made history. He won Puerto Rico's first Olympic medal, a bronze, in boxing. This was also the first time Puerto Rico competed as its own nation in an international sports event. Many poor Puerto Ricans used boxing to earn money.

On March 30, 1965, José "Chegui" Torres won the World Boxing Council and World Boxing Association light heavyweight boxing titles. He was the third Puerto Rican and the first Afro–Puerto Rican to win a professional world championship.

Jesús Colón was one of the people who spoke out about unfair treatment in the US. He is seen as the "Father of the Nuyorican movement." He wrote about his experiences as a Black Puerto Rican in New York in his book Lo que el pueblo me dice.

Some people say that most Puerto Ricans are of mixed race. But they don't always feel the need to say so. They believe that Puerto Ricans generally think they have Black African, American Indian, and European ancestors. They only identify as "mixed" if their parents look very different in race. Puerto Rico went through a "whitening" process under US rule. The number of people called "Black" in the 1920 census dropped sharply from 1910. Historians think more Puerto Ricans were classified as white because it was helpful at that time. Census takers often decided a person's race back then. The US Census stopped using the "mulatto" or mixed-race category in 1930. This forced people into being either Black or white. People could not choose their own race on the census until much later. It was thought that being "white" would make it easier to get ahead in the US.

African Culture in Puerto Rico

The descendants of former enslaved people helped shape Puerto Rico's government, economy, and culture. They faced many challenges. But they contributed to the island's entertainment, sports, writing, and science. Their contributions are still seen today in Puerto Rican art, music, food, and religious beliefs. In Puerto Rico, March 22 is "Abolition Day," a holiday celebrating the end of slavery.

The first Black people on the island came with European settlers. They were workers from Spain and Portugal called Ladinos. In the 1500s, Spain brought most enslaved people to Puerto Rico from the Upper Guinea region. But in the 1600s and 1700s, many came from Lower Guinea and the Congo. DNA studies show that most African ancestry in Puerto Ricans comes from tribes like the Wolof, Mandinka, Dahomey, Yoruba, Igbo, and Congolese. These groups are from countries like Senegal, Mali, Benin, Nigeria, and Angola today. The Yoruba and Congolese people had the biggest impact on Puerto Rican culture.

Language

Many enslaved Africans brought to Cuba and Puerto Rico spoke "Bozal" Spanish. This was a mix of Spanish, Congolese, and Portuguese. Even though Bozal Spanish is no longer spoken, African influence is still in Puerto Rican Spanish. Many Kongo words are now a permanent part of the language.

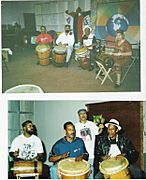

Music and Dance

Puerto Rican musical instruments like barriles (drums made with animal skin) have African roots. Music and dance styles like Bomba and Plena also come from Africa. Bomba shows the strong African influence in Puerto Rico. It is a music, rhythm, and dance style brought by West African enslaved people.

Plena is another type of folk music with African origins. It came to Ponce from Black people who moved from English-speaking islands south of Puerto Rico. Plena has a clear African rhythm. It is very similar to Calypso, Soca, and Dancehall music from Trinidad and Jamaica.

Bomba and Plena were played during the festival of Santiago (St. James). Enslaved people were not allowed to worship their own gods. Bomba and Plena grew into many styles. These included leró, yubá, cunyá, babú, and belén. Enslaved people celebrated baptisms, weddings, and births with "bailes de bomba." Slave owners allowed these dances on Sundays, fearing rebellions. Women dancers would make fun of the slave owners. Masks were, and still are, worn to scare away evil spirits. One popular masked character is the Vejigante. The Vejigante is a playful character and a main part of Puerto Rico's Carnivals.

Until 1953, Bomba and Plena were not well known outside Puerto Rico. Musicians Rafael Cortijo and Ismael Rivera introduced them to the world. Rafael Cortijo modernized these rhythms. He added piano, bass, saxophones, trumpets, and other drums like timbales and congas.

Food

Puerto Rican food also has strong African influences. The mix of flavors in typical Puerto Rican dishes includes an African touch. Pasteles are small bundles of meat wrapped in a dough made from grated green banana. They are wrapped in plantain leaves. African women on the island created them using foods from Africa.

The salmorejo, a local crab dish, tastes similar to Southern cooking in the United States. Mofongo, a famous island dish, is a ball of fried mashed plantain. It is stuffed with pork, crab, lobster, or shrimp. Puerto Rico's food celebrates its African roots. It blends them with Indian and Spanish influences.

Religion

In 1478, the Catholic rulers of Spain created the Spanish Inquisition. This was to keep Catholic beliefs strong. The Inquisition did not have a court in Puerto Rico. But people accused of not following Catholic rules could be sent to courts in Spain. Africans were not allowed to practice their traditional religions. No single African religion from slavery times survived completely in Puerto Rico. But many African spiritual beliefs mixed with other ideas and practices.

Santería is a mix of Yoruba and Catholic beliefs. Palo Mayombe comes from Kongolese traditions. Both are practiced in Puerto Rico. A smaller number of people practice Vudú, which comes from Dahomey beliefs.

Palo Mayombe existed for centuries before Santería. The town of Guayama was even called "the city of witches" because this religion was common there. Santería is believed to have started in Cuba among enslaved people. Yoruba people were brought to many places in the Caribbean and Latin America. They kept some of their traditions. In Puerto Rico, Christianity was dominant. But even though they became Christian, Africans did not completely give up their old religious practices. Santería mixes images from the Catholic Church with gods from the African Yoruba people of Nigeria. Santería is widely practiced in the town of Loíza.

Santería has many gods called "Orishas." These gods are believed to come from heaven to help their followers. The Orishas choose which person they will watch over.

In Santería, not everyone who worships is a "Santero." Santeros are the priests and official practitioners. (These "Santeros" are different from Puerto Rican artists who carve religious statues from wood, who are also called Santeros). A person becomes a Santero after passing certain tests and being chosen by the Orishas.

Afro–Puerto Ricans Today

The 2020 Census was the first to let people choose more than one race. This shows Puerto Rico's mixed history. In 2020, 17.5% of Puerto Ricans identified as white. 17.5% identified as Black or Black mixed with another race. 2.3% identified as American Indian. 0.3% as Asian. And 74% as "Some Other Race Alone or in Combination." Most sources believe about 60% of Puerto Ricans have a lot of African ancestry. Most Black people in Puerto Rico are Afro–Puerto Rican. This means their families have been there for generations, often since the slave trade. They are a big part of Puerto Rican culture.

Recently, more Black immigrants have come to Puerto Rico. They are mainly from the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and other Latin American and Caribbean countries. Some also come directly from Africa. Many Black migrants from the United States and the Virgin Islands have also moved to Puerto Rico. Also, many Afro–Puerto Ricans have moved out of Puerto Rico, especially to the United States.

Under Spanish and American rule, Puerto Rico went through a "whitening" process. In the early 1800s, about 50% of the population was Black or mixed-race. By the mid-1900s, nearly 80% were classified as white. Under Spanish rule, laws like Regla del Sacar allowed people with mixed African-European ancestry to be considered white. This was the opposite of the "one-drop rule" in the US. The Spanish government's Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 also encouraged Europeans to move to the island. This increased Puerto Rico's population to about one million by the late 1800s. In the early 1900s, US census takers started classifying more people as "white." This led to a "whitening" process from the 1910 to 1920 census.

Afro–Puerto Rican youth are learning more about their history. Textbooks now include more Afro–Puerto Rican history. The 2010 US census showed the first drop in the percentage of white people in Puerto Rico in over a century. It also showed the first rise in the Black percentage. This trend might continue because more Puerto Ricans are identifying as Black. This is due to growing Black pride and African cultural awareness. Also, more Black immigrants are coming, and more white Puerto Ricans are moving to the US.

The following list shows the towns with the highest percentages of residents who identify as Black in 2020:

- Loiza: 64.7%

- Canóvanas: 33.4%

- Maunabo: 32.7%

- Rio Grande: 32%

- Culebra: 27.7%

- Carolina: 27.3%

- Vieques: 26%

- Arroyo: 25.8%

- Luquillo: 25.7%

- Patillas: 24.1%

- Ceiba: 23.8%

- Juncos: 22.9%

- San Juan: 22.2%

- Toa Baja: 22.1%

- Salinas: 22.1%

- Cataño: 21.8%

Famous Afro–Puerto Ricans

- Rafael Cordero (1790–1868) was born free in San Juan, Puerto Rico. He was known as "The Father of Public Education in Puerto Rico." Cordero taught himself and gave free schooling to children of all races. Some of his students became important abolitionists. Cordero showed that people of different races and backgrounds could learn together. In 2004, the Catholic Church began the process to make him a saint. His older sister, Celestina Cordero, also started the first school for girls in San Juan in 1820.

- José Campeche (1751–1809) was a free man who greatly contributed to the island's culture. His father was a freed enslaved person, and his mother was from the Canary Islands. Because his mother was considered white, her children were born free. Campeche was of mixed race and was called a mulatto in his time. He is considered the most important Puerto Rican painter of religious art from his era.

- Capt. Miguel Henriquez (c. 1680–17??) was a former pirate. He became Puerto Rico's first Black military hero. He led a group that defeated the British in Vieques. He was welcomed as a national hero and given a special medal. The Spanish King named him "Captain of the Seas."

- Rafael Cepeda (1910–1996), known as "The Patriarch of Bomba and Plena," led the Cepeda family. This family is famous for Puerto Rican folk music. Generations of musicians have worked to keep African heritage alive in Puerto Rican music. They are seen as the guardians of Bomba and Plena.

- Sylvia del Villard (1928–1990) was part of the Afro-Boricua Ballet. She performed in Afro–Puerto Rican shows. In 1968, she started the Afro-Boricua El Coqui Theater. This group was recognized for its work in Black Puerto Rican culture. They performed in other countries and at universities in the United States. In 1981, del Villard became the first director of the Office of Afro–Puerto Rican Affairs. She was a strong activist who fought for equal rights for Black Puerto Rican artists.

In Stories

- The Marvel superhero Spider-Man in the alternate Ultimate Marvel universe is of African American and Puerto Rican descent. Miles Morales, the current Spider-Man, has an African American father and a Puerto Rican mother.

Images for kids

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |