History of Minneapolis facts for kids

Minneapolis is the biggest city in Minnesota, a state in the United States. It's the main city of Hennepin County. Minneapolis grew because of two main things: Fort Snelling, an early U.S. military base, and Saint Anthony Falls. The falls provided powerful water to run sawmills and flour mills.

Fort Snelling was built in 1819 where the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers meet. Soldiers there used the falls for power. When land became available, two towns started on opposite sides of the falls: Saint Anthony on the east and Minneapolis on the west. These two towns joined together in 1872. At first, sawmills were important, but flour mills soon took over. This led to the growth of railroads, banks, and the Minneapolis Grain Exchange. Thanks to new ways of milling, Minneapolis became a world leader in making flour, earning it the nickname "Mill City." As the city grew, its culture developed with churches, art places, the University of Minnesota, and a famous park system.

Even though the old sawmills and flour mills are gone, Minneapolis is still a big center for banking and industry. The two largest milling companies, General Mills and the Pillsbury Company (now part of General Mills), are still important in the area. The city has also made its riverfront beautiful again, with parks, the Mill City Museum, and the Guthrie Theater.

Contents

Exploring the Early Days of Minneapolis

First European Visits to the Falls

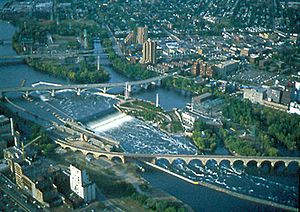

Minneapolis grew around Saint Anthony Falls. This is the only waterfall on the Mississippi River. For a long time, boats couldn't go past it until locks were built in the 1960s.

A French explorer named Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut came to Minnesota in 1680. He wanted to expand French control. While exploring the St. Croix River, he heard that some other explorers were captured. He helped free them. Among them was Father Louis Hennepin, a Catholic priest. Father Hennepin explored the falls and named them after his favorite saint, Anthony of Padua. He wrote a book in 1683 called Description of Louisiana, telling Europeans about the area. He sometimes made things sound bigger than they were. For example, he said the falls were fifty or sixty feet high, but they were only about 16 feet (4.9 m).

How the Land Became Part of the U.S.

The land where Minneapolis is now was bought by the United States through agreements with the Mdewakanton Dakota people and European countries. England claimed the land east of the Mississippi. France, then Spain, and then France again claimed the land west of the river. In 1787, the east side became part of the Northwest Territory. In 1803, the west side became part of the Louisiana Purchase. Both were claimed by the United States.

In 1805, Zebulon Pike bought two areas of land from the Dakota people. One was at the mouth of the St. Croix River. The other, larger area, went from where the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers meet up to St. Anthony Falls. It was nine miles (14 km) wide on both sides of the river. In return, he gave about $200 worth of goods and some liquor. He also promised more payment from the U.S. government. The United States Senate later approved a payment of $2,000.

Fort Snelling and the Mills

Building Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling was built in 1819. Its purpose was to extend U.S. control over the area. Soldiers first camped on the south side of the Minnesota River. It was a tough winter, and many soldiers got sick. They moved their camp to Camp Coldwater in May 1820. This spring was important to the native Dakota people.

The soldiers needed supplies for the fort. They built roads, grew vegetables and wheat, and raised cattle. They also started keeping weather records. In 1822, a lumber mill and a grist mill were built at the falls to help supply the fort.

Claiming Land and Building Mills

In the 1830s, Joseph Plympton, a commander at Fort Snelling, wanted to start a settlement on the east bank of the Mississippi near St. Anthony Falls. He mapped out the fort's land, but made sure to leave out some parts of the east bank. He planned to claim land at the falls. However, Franklin Steele also had plans.

On July 15, 1838, news arrived that a treaty between the U.S. and the Dakota and Ojibwa people was approved. This treaty gave land between the St. Croix River and the Mississippi to the U.S. Steele quickly went to the falls, built a small shelter, and marked his land. Plympton's group arrived the next morning, but they were too late for the best land. Steele then built a dam at the falls and a sawmill.

The Dakota people were hunters and gatherers. They soon owed money to fur traders. Because of sickness, less wildlife, and forests being cut down, the Mdewakanton Dakota sold the rest of their land west of the river in 1851. This allowed more people to settle there in 1852.

Franklin Steele also found a way to get land on the west side of the falls. He suggested that his friend, Colonel John H. Stevens, should ask the War Department for some land. Stevens agreed to run a ferry service across the Mississippi. In return, he got 160 acres (0.6 km2) of land just above the government mills. This deal was approved. Stevens built his house in the winter of 1849–1850. It was the first permanent home on the west bank in what became Minneapolis. Later, the amount of land controlled by the fort was reduced by U.S. President Millard Fillmore. Soon, the village of Minneapolis quickly grew on the southwest bank of the river.

City Pioneers and Growth

Starting St. Anthony

After Franklin Steele officially owned his land, he focused on building a sawmill at St. Anthony Falls. He got money and built a dam on the east side of the river. His partner, Daniel Stanchfield, sent crews up the Mississippi to start cutting lumber. The sawmill began cutting wood in September 1848. In October 1848, Steele hired Ard Godfrey to manage the mill.

Steele planned a town in 1849 and named it "St. Anthony." The town grew fast with workers. Besides the first sawmill, other sawmills and a grist mill were built in 1851. By 1855, about 3,000 people lived there, and it became a city. Godfrey's house, built in 1848, was later moved to Chute Square and is now a historic site.

Naming Minneapolis

On the west side of the river, John H. Stevens planned a town in 1854. He laid out Washington Avenue parallel to the river. Other streets ran parallel and perpendicular to Washington. The streets were wide and straight, much wider than those in Saint Paul.

The early community tried several names, but none stuck. Minneapolis has many small lakes. This led Charles Hoag, the first schoolmaster, to suggest Minnehapolis. This name came from "Minnehaha" and mni, a Dakota word for water, and polis, a Greek word for city.

The Minnesota government recognized Saint Anthony as a town in 1855 and Minneapolis in 1856. Minneapolis became a city in 1867. Minneapolis and Saint Anthony joined together in 1872. In 1873, Minneapolis changed over 100 road names to avoid confusion with the former Saint Anthony.

Transportation Develops

The Hennepin Avenue Bridge was the first bridge built across the entire Mississippi River. It was a suspension bridge built in 1854 and opened on January 23, 1855. It was 620 feet (190 m) long and 17 feet (5.2 m) wide. It cost $36,000 to build. People paid five cents to walk across and twenty-five cents for horse-drawn wagons.

Early settlers wanted railroads, but there wasn't enough money after a financial crisis in 1857. Rails were finally built in Minnesota in 1862. The St. Paul and Pacific Railroad built its first ten miles (16 km) of track from St. Paul to near St. Anthony Falls. The railroad kept building tracks to places like Elk River and St. Cloud. Another railroad, the Minnesota Central, built a line from Minneapolis to Fort Snelling in 1865. This line eventually connected Minneapolis to Milwaukee in 1867.

A streetcar system started in Minneapolis in 1875. The Minneapolis Street Railway company began with horse-drawn cars. Under Thomas Lowry, the company merged and became Twin City Rapid Transit. By 1889, when electric streetcars began, the system had grown to 115 miles (185 km) of track.

Cultural Growth in Minneapolis

Education in the City

The University of Minnesota was founded in 1851, seven years before Minnesota became a state. It started as a school to prepare students for college. The school closed during the American Civil War due to money problems. But with help from John S. Pillsbury, it reopened in 1867. William Watts Folwell became the first president in 1869. The university gave its first degrees in 1873. It grew from the St. Anthony area to a large campus on the east bank of the Mississippi. It also added a campus in St. Paul and a West Bank campus in the 1960s.

DeLaSalle High School was started by Archbishop John Ireland in 1900. It was a Catholic high school. At first, it focused on business skills. But by 1920, parents wanted a school that prepared students for college. The school has been open for over 100 years on Nicollet Island.

Minneapolis Parks

The first park in Minneapolis was land given to the city in 1857. But it took about 25 years for people to really care about parks. City leaders asked the Minnesota government for help. On February 27, 1883, the government allowed the city to create a park district and collect taxes for parks. The idea was to build many boulevards (wide streets with trees) that would connect parks. These ideas came from Frederick Law Olmsted.

Landscape architect Horace Cleveland was hired to create a system of parks called the "Grand Rounds." Lake Harriet was given to the city in 1885. The first bandshell (a stage for music) on the lake was built in 1888. The current bandshell, built in 1985, is the fifth one there.

Minnehaha Falls was bought as a park in 1889. The park was named after a character in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's famous poem, The Song of Hiawatha.

In 1906, Theodore Wirth became the parks superintendent in Minneapolis. During his time, the park system grew a lot. It went from 1,810 acres (7.3 km²) to 5,421 acres (21.9 km²). The park system, built around Minneapolis's chain of lakes (like Cedar Lake, Lake of the Isles, Lake Calhoun, and Lake Harriet), became a model for park planners worldwide. He also encouraged people to be active in the parks, not just look at them.

Arts and Culture

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts was started in 1883 by twenty-five citizens. They wanted to bring fine arts to Minneapolis. The main building, a neoclassical style, opened in 1915. It later had additions in 1974 and 2006.

The Minnesota Orchestra began in 1903 as the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. It changed its name in 1968 and moved into its own building, Orchestra Hall, in 1974.

The Walker Art Center opened in 1927. It was the first public art gallery in the Upper Midwest. In the 1940s, the museum started focusing on modern art. This was thanks to a gift that allowed them to buy works by artists like Pablo Picasso and Henry Moore. The museum is now one of the "big five" modern art museums in the U.S.

Historic Churches

Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church was founded in 1854. It is the oldest church in Minneapolis that has been used continuously. The church was first built by the First Universalist Society. It became a Catholic church in 1877.

The Basilica of Saint Mary was built between 1907 and 1915. Archbishop John Ireland oversaw the planning of this church, along with the Cathedral of St. Paul in Saint Paul. He chose architect Emmanuel Masqueray, who studied in Paris. The first Mass was held on May 31, 1914. Church leaders wanted to build the best altar in America. It became the first basilica in the United States in 1926. The building is famous for its Beaux-Arts architecture.

Minneapolis Changes Over Time

The Decline of Flour Mills

In the early 1900s, Minneapolis started to lose its top spot in the flour milling industry. This happened after its peak in 1915–1916. Steam power and later electric power meant that water power from St. Anthony Falls was no longer such a big advantage. Also, the wheat fields in the Dakotas and Minnesota started having problems with soil and plant diseases. Farmers in the southern plains grew a new type of wheat good for bread flour, and the Kansas City area became important for milling. Changes in train shipping costs also made it cheaper for mills in Buffalo, New York to send their flour.

In response, companies like Washburn-Crosby Company and Pillsbury started selling their flour directly to people. Washburn-Crosby named their flour "Gold Medal" and used the slogan "Eventually – Why Not Now?" Pillsbury used "Because Pillsbury's Best." Washburn-Crosby created the character Betty Crocker to answer customer questions. They also bought a radio station in 1924 and named it WCCO, which stood for "Washburn Crosby Company."

In 1928, Washburn-Crosby merged with other milling companies and became General Mills. Both General Mills and Pillsbury started making other products besides flour. They held baking contests and published recipes. They also developed easy-to-make foods like Bisquick and ready-to-eat cereals like Wheaties.

After 1930, the flour mills slowly closed down. Their buildings were left empty or torn down. The train tracks that served the mills were removed. The old mill canals were filled in. The last two mills at the falls were the Washburn "A" Mill and the Pillsbury "A" Mill. In 1965, General Mills closed the Washburn "A" Mill and other old mills. All milling in the city stopped by the early 20th century.

To keep using the river for business, city leaders wanted to build locks and dams. This would allow boats to travel above Saint Anthony Falls for the first time. Congress approved the project in 1937. From 1950 to 1963, the United States Army Corps of Engineers built two sets of locks at the lower dam and the falls. They also covered the falls with a concrete layer. This project also changed the Stone Arch Bridge, replacing two of its arches with a steel truss.

Changes in Politics and Society

Hubert Humphrey started his political career in Minnesota in the early 1940s. He helped the Democratic Party merge with the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party. This new party was called the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party.

Humphrey first ran for mayor of Minneapolis in 1943 but lost. He ran again in 1945. He had support from labor leaders and the city's African-American community. He promised to create a city civil rights commission. He also appealed to the middle class by talking about good citizenship. He won the election by a large margin.

As mayor, Humphrey immediately suggested a city law to fine employers who discriminated based on race. After much discussion, the Minneapolis City Council approved the law on January 31, 1947. This was the nation's first Fair Employment Practices Ordinance. It made Minneapolis a leader in fighting job discrimination. The law gave the new Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) the power to fine and even imprison employers who discriminated. Larger banks and stores started hiring more African-Americans. Humphrey also told the police chief to have officers in minority neighborhoods talk to community leaders. This helped solve problems of prejudice.

Humphrey's work on civil rights in Minneapolis got national attention. Many cities asked how they could set up their own civil rights commissions. In 1947, he was reelected mayor by a huge margin. At the 1948 Democratic National Convention, he pushed for strong civil rights. He said, "There are those who say to you – we are rushing this issue of civil rights. I say we are 172 years late." Humphrey was elected to the United States Senate in 1948. He served many years as a major Minnesota politician, including Vice President of the U.S. from 1965–1969.

W. Harry Davis ran for mayor in 1971. He was the city's first black mayoral candidate supported by a major political party. He and his family faced threats during the campaign. The police and FBI protected them. Davis also got support from white politicians like Humphrey. Twenty years later, Minneapolis elected its first African American mayor, Sharon Sayles Belton. She is still the city's only non-white mayor.

In 1968, Dennis Banks and Clyde Bellecourt helped start the American Indian Movement. This group worked for civil rights for Native Americans.

A Growing City and Its Transportation

Minneapolis's population grew from about 200,000 in 1900 to over 521,000 in 1950. This growth was partly due to an organized private streetcar system. By 1920, 140 million passengers used the streetcars. They ran on important roads from Downtown Minneapolis. Neighborhoods outside the city center grew around the turn of the century because of this system. This growth also allowed Minneapolis to add land from nearby villages.

The streetcar system was built by Twin City Rapid Transit. It ran well until 1949. The company used its profits to improve the system. However, in 1949, a New York investor named Charles Green took control. He stopped the improvements and announced he wanted to switch completely to buses by 1958. People didn't like these changes, and he was removed in 1951. But his replacement, Fred Ossanna, continued to cut service and replace streetcars with buses. On June 19, 1954, the last streetcar ran. Later, it was found that Ossanna and others had misused money from the streetcar system for themselves. A small part of the old streetcar line between Lake Calhoun and Lake Harriet is now run by the Minnesota Streetcar Museum.

Reshaping Downtown Minneapolis

Downtown Minneapolis was the center of business and finance. The Minneapolis City Hall was the tallest building from 1888 until 1929. A city rule in 1890 limited buildings to 100 feet (30 m) tall, later raised to 125 feet (38 m). The First National – Soo Line Building was built in 1915 and was 252 feet (77 m) tall. This worried the real estate industry, so the 125 feet (38 m) limit was put back.

The twenty-seven story Rand Tower, built in 1929, was the next tall building. The thirty-two story Foshay Tower, also built in 1929, was the tallest building in Minneapolis until 1971. Its builder, Wilbur Foshay, wanted a tower like the Washington Monument. He had a big opening ceremony with music by John Philip Sousa. About six weeks later, Foshay lost all his money in the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Foshay's check to Sousa bounced, and Sousa said no one could play his music until the debt was paid.

During the Great Depression, buildings were not well cared for. Writer Sinclair Lewis said Minneapolis looked "ugly" with "parking lots like scars." After World War II, businesses and people started moving to the suburbs. Downtown Minneapolis, like other downtowns, seemed to be dying. City planners wanted to rebuild downtowns completely. The Federal Housing Act of 1949 gave money to clear "blighted" (run-down) areas. The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 provided money for interstate highways, which also changed Minneapolis.

The Gateway district, near Hennepin Avenue and Nicollet Avenue west of the Mississippi River, was greatly changed by urban renewal. This area was known for cheap hotels. When General Mills announced in 1955 they were moving their headquarters, city planners decided to tear down many buildings in the Gateway district. Between 1957 and 1965, one-third of downtown Minneapolis was leveled, including the Metropolitan Building.

Building freeways also changed the city. Neighborhoods were broken up, and homes were lost. From 1963 to 1975, Interstate 35W and Interstate 94 were built. Some planned highways were never built because people in the neighborhoods opposed them.

Modern Minneapolis

Changing the Skyline

Even though the Gateway district was destroyed, other projects changed downtown Minneapolis and its skyline. One big change was the Nicollet Mall in 1968. This part of Nicollet Avenue became a tree-lined area for people walking and public transport. It's like a long park with trees and fountains. It also helped the city's stores. The biggest change to the skyline came in 1974 when the IDS Center opened. At 775 feet 6 inches (236.37 m) tall, it was much taller than the Foshay Tower. Other tall buildings added to downtown included 33 South Sixth (1983), the Wells Fargo Center (1988), and Capella Tower (1992).

The Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome, opened in 1982 and torn down in 2014, was home to the Minnesota Vikings football team. The site is now being rebuilt as a new stadium. In the 1990s, more towers were built downtown, including buildings for Target and Ameriprise Financial.

Tall residential buildings also followed. In the 1970s, many high-rise condos were built in the old milling areas and Downtown West. Riverside Plaza, finished in 1973, was a group of six towers for different income levels. More modern residential towers with different colors and styles were built in the late 1990s and 2000s. The Carlyle residence, built in art deco style, is 41 stories tall.

Light rail trains started in Minneapolis with the Blue Line on June 26, 2004. This line goes from downtown Minneapolis southeast, past Minnehaha Park, and serves the Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport. It ends at the Mall of America in Bloomington. In 2014, the Green Line opened, connecting downtown with the University of Minnesota and downtown St. Paul.

Rediscovering the Riverfront

As factories and railroads left the Mississippi riverfront, people realized the riverfront could be a great place to live, work, and shop. The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board bought land along the river, including much of Nicollet Island and Boom Island. These areas were developed with trails and parkways. This encouraged private companies to build homes and businesses next to the river, creating the new Mill District neighborhood.

The Stone Arch Bridge opened for people walking in 1994. It became part of the trail system and offers great views of Saint Anthony Falls. Some old commercial buildings were given new uses. The Whitney Hotel is in what used to be the Standard Mill. The North Star Lofts used to be the North Star Woolen Mills building. Other projects, like Saint Anthony Main and many condos, let people live with views of Saint Anthony Falls.

Digging up old sites along the riverfront has found parts of the flour mills built in the 1860s and 1870s. They also found the tailrace canal that once supplied water to the mills and the supports for the Minnesota Eastern Railroad. These old ruins, which were once buried, are now open to the public as Mill Ruins Park. The park has signs explaining the history of the area.

The Washburn "A" Mill, badly damaged by a fire in 1991, is now the Mill City Museum. It opened in 2003. The museum tells the story of flour milling and industry along the river. An eight-story elevator ride shows how wheat was turned into flour. The Guthrie Theater moved to a new building along the riverfront in 2006, near the Mill City Museum.

Images for kids

-

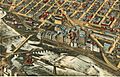

A lithograph from 1895 showing how important the Mills District was.