History of Provence facts for kids

Provence is a historic region in the southeast of France. It sits between the Alps mountains, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Rhône River. People have lived here for a very long time. First, there were the Ligures in the Stone Age. Then came the Celts around 900 BC, and Greeks around 600 BC. The Romans conquered Provence in the late 2nd century BC. For many centuries, from 879 to 1486, Provence was a state ruled by its own Counts of Provence. In 1486, Provence officially became part of France. Even after hundreds of years, people in Provence still have a strong cultural identity.

Contents

- Why is it Called Provence?

- Ancient Times in Provence

- Ligures and Celts: Early Tribes

- The Greeks Settle in Provence

- Roman Provence: A New Era

- Christianity Arrives in Provence

- Barbarians and Merovingians

- Franks and Arabs in Provence

- The Counts of Provence

- Expelling the Saracens

- Catalan Dynasty and Growing Cities

- Cathedrals and Monasteries

- Battles for Provence

- Popes in Avignon

- Good King René: The Last Ruler

- Provence Becomes French

- The French Revolution

- Provence Under Napoleon and Beyond

- Provence in the 19th Century

- Provence in the 20th Century

- See also

Why is it Called Provence?

The name "Provence" comes from Roman times. The Romans called this area Provincia Romana, which simply meant "the Roman province." Over time, this name became shorter, just "Provincia." As the language changed from Latin to Provençal, the name also changed to what we know today as Provence.

Ancient Times in Provence

The coast of Provence has some of the oldest places where humans lived in Europe. Very old stone tools, dating back over a million years, have been found near Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. At Terra Amata in Nice, scientists found signs of an ancient camp on a beach. There were even traces of some of the earliest fireplaces in Europe, from about 400,000 BC.

During the paleolithic age, people in Provence lived in caves or simple huts. They used tools to get meat from animals killed by predators like saber-toothed tigers. They lived through two ice ages, which changed the climate and even the sea level.

In 1985, a diver found a cave entrance 37 meters (121 feet) under the sea near Marseille. Inside, the Cosquer Cave has amazing drawings of animals like bison, seals, and penguins. There are also outlines of human hands. These drawings are between 27,000 and 19,000 years old.

Around 8,500 BC, the climate warmed up. The sea rose, and forests grew. People had to find new ways to survive, eating smaller animals like rabbits and snails. Around 6000 BC, the Castelnovien people were among the first in Europe to tame wild sheep. This allowed them to stay in one place and create the first pottery in France. Later, new groups of farmers and warriors, like the Chasséens and Courronniens, arrived and settled in Provence.

Ligures and Celts: Early Tribes

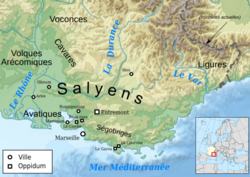

Around the 4th century BC, the Ligures lived in Provence, from the Alps to the Rhône River. They were likely descendants of the Stone Age people. They didn't have their own alphabet, but their language is still seen in some place names today. They were known for being tough and warlike.

Later, between the 8th and 5th centuries BC, Celts arrived from Central Europe. They had iron weapons, which were better than the bronze weapons of the Ligures. The Celts and Ligures eventually shared the land. They built forts on hilltops, called oppida. Today, we can still find traces of hundreds of these forts. They worshipped nature, like sacred woods and healing springs. Over time, different tribes formed larger groups, like the Salyens.

The Celto-Ligures traded iron, silver, and other goods using the Rhône River. Etruscan traders from Italy also visited the coast. You can still see traces of these ancient people in the ruins of their forts, in large stone monuments called dolmens, and in rock carvings.

The Greeks Settle in Provence

Traders from the Greek island of Rhodes visited the coast of Provence in the 7th century BC. They even gave their name to the Rhône River.

The first permanent Greek settlement was Massalia, founded around 600 BC by colonists from Phocaea (in modern Turkey). Massalia grew into a major trading port. It had about 6,000 people and was surrounded by a wall. It was run by an assembly of its wealthiest citizens. Massalia minted its own coins, which were found all over Gaul (ancient France). They traded wine, salted fish, and other goods far into Europe.

The Massalians also founded smaller colonies along the coast, which later became towns like Antibes and Nice. Their culture influenced the people living inland.

One famous person from Massalia was Pytheas, a mathematician and explorer. He was the first scientist to notice that tides were connected to the moon. Between 330 and 320 BC, he sailed into the Atlantic, reaching places like England and Norway. He was the first to describe drift ice and the midnight sun.

Roman Provence: A New Era

How Rome Conquered Provence

In 218 BC, when Hannibal marched his army through Provence to attack Rome, Massalia and Rome became allies. The Romans helped Massalia against local tribes. However, Rome wanted to control the region, not just be an ally.

In 125 BC, a group of Celtic people called the Salyes threatened Massalia. Rome sent an army, led by Marcus Fulvius Flaccus, who defeated them. Another Roman general, Gaius Sextius Calvinus, destroyed the Salyes' main fort and founded a new Roman town called Aquae Sextiae, which later became Aix-en-Provence.

More battles followed, with Roman generals like Domitius Ahenobarbus and Quintus Fabius Maximus defeating large Gallic armies. In 118 BC, the Romans founded their first colony outside Italy, Narbo Martius (now Narbonne). This whole area became a Roman province.

Around 109 BC, huge Germanic tribes, the Teutons and Cimbri, moved south into Gaul. The Romans sent their best general, Gaius Marius, to Provence. He waited patiently, then defeated the Teutons near Aix in 102 BC. This made Provence safe from invasion for a long time.

Julius Caesar governed this Roman province from 58 to 49 BC. He used it as a base for his famous wars in Gaul.

In 49 BC, Massalia made a big mistake by supporting Pompey against Julius Caesar in a Roman civil war. Caesar besieged the city and captured it. Massalia lost its independence and most of its lands. The final Roman conquest of the mountain tribes happened between 24 BC and 14 BC under Emperor Augustus Caesar. He built a monument at La Turbie to celebrate this victory.

The Roman Peace in Provence

The Pax Romana, or Roman Peace, lasted for almost 300 years in Provence. During this time, Provence had the same language, government, money, and culture. People felt safe enough to move from their hilltop forts to towns in the plains. Pliny the Elder even said Provence was "more than a province, it was another Italy."

The Romans built many towns and a system of roads. Julius Caesar founded three colonies for his army veterans: Fréjus, Arles, and Orange, Vaucluse. These citizens had full Roman rights. Other towns were also founded or transformed from Gallic villages.

Roman engineers built strong, well-maintained roads. The Via Domitia connected Italy to Spain through Provence. The Via Aurelia ran along the coast, and the Via Agrippa went up the Rhône Valley.

After Massalia lost its power, Arles became the most important economic center. It had a key bridge over the Rhône and was a meeting point for trade routes. Provence produced wheat, oil, and various meats.

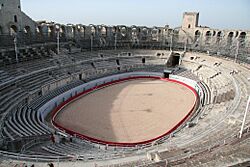

Roman wealth and culture were visible everywhere. The Roman amphitheater at Arles could hold 20,000 people. Romans built monuments, theaters, baths, and aqueducts throughout Provence. Many of these still exist today.

The Roman Peace ended in the middle of the 3rd century. Germanic tribes invaded in 257 and 275 AD. By the end of the 5th century, Roman rule in Provence was gone, leading to a time of invasions and chaos.

Christianity Arrives in Provence

In the late Roman Empire, Provence was mostly spared from invasions that hit other parts of Gaul. Its ports, like Marseille, continued to trade with the Mediterranean world.

People in Roman Provence worshipped many gods and religions. They worshipped local goddesses, nature gods, and traditional Roman gods like Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. They also worshipped the Roman emperors. Later, Eastern religions like the cult of Mithra and the Egyptian goddess Isis became popular.

There are many legends about early Christians in Provence. Some say that Lazarus, healed by Jesus, became a bishop in Arles. Another legend says his sister Martha came to Tarascon. Others claim Mary Magdalene, Mary Salome, and Mary Jacobe arrived by boat at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. While these legends are popular, there is no historical proof for them.

The Christian Church began sending missionaries to Provence in the 3rd century. By the 4th century, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. Churches were built in all major cities, often using parts of old Roman temples. The oldest Christian building still standing in Provence is the baptistery of the cathedral in Fréjus, from the 5th century.

Around the same time, the first two monasteries were founded: Lérins Abbey near Cannes and Saint-Victor in Marseille. These monasteries became important centers for learning and religious teaching.

Barbarians and Merovingians

In 412 AD, the Visigoths passed through Provence after capturing Rome. They tried to attack Arles several times. Roman power could no longer defend Provence. Other tribes, like the Burgundians, also moved into the region. In 476, the last Western Roman Emperor was removed, and the Visigoths entered Arles and Marseille without a fight.

The Visigoths and Burgundians divided Provence. They took land and slaves for themselves. Each city was ruled by a count, and groups of cities by a duke. Marseille's trade with the Mediterranean helped it grow again.

The Visigoths' rule was short. Their king was defeated by Clovis I, King of the Franks, in 507. Another group, the Ostrogoths, then took control of parts of Provence. Under their rule, Provence was loosely connected to the Eastern Roman Empire.

After about 30 years, the Merovingian kings of the Franks took over Provence. These kings lived far to the north and rarely visited. Provence suffered from constant conflicts, attacks by other raiders, and diseases. Roman buildings and irrigation systems fell apart. People left the cities and moved to fortified villages on hilltops. Only Marseille, with its trade, continued to do well.

The Merovingian rule also set the northern border of Provence, which is still roughly the same today.

Franks and Arabs in Provence

Starting in the 8th century, Provence became a battleground between the Frankish kings and the expanding Arab power from the Mediterranean. Charles Martel, a Frankish leader, defeated the Arabs at the Battle of Tours in 732, stopping their advance north. But the Arabs remained strong on the coast.

Some towns in Provence rebelled against Charles Martel, even asking the Arabs for help. Charles Martel invaded Provence several times to regain control, often with harsh punishments.

The reign of Charlemagne (768-814) brought some peace to Provence, but the region remained very poor. Trade had stopped, and people lived mostly from farming.

After Charlemagne's death, his empire broke apart, and Provence faced new troubles. Arab pirates attacked Marseille in 838, destroying the Abbey of Saint Victor. Other pirates and Normans also raided the coast and the Rhône Valley.

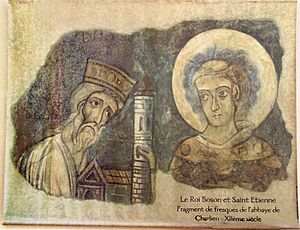

In 855, a short-lived Kingdom of Provence was created. Later, in 879, Boso of Provence declared himself King of Provence. After some conflict, his son Louis became King of an independent Provence in 890.

The Counts of Provence

For four centuries, Provence was ruled by Counts or Marquises. They were mostly independent, even though they were technically under larger empires.

One of these rulers, Louis the Blind, tried to become King of Italy and Emperor. He was crowned Emperor in Rome in 901, but was later defeated and blinded. He returned to Provence and ruled until his death in 928.

His cousin, Hugh of Italy, then effectively governed Provence, moving the capital to Arles. Hugh also became King of Italy. He eventually returned to Arles and became a monk. After Hugh's death, the title of Count of Provence passed to Conrad of Burgundy. A new dynasty of Counts of Provence began with Rotbald of Arles.

Expelling the Saracens

While the Counts were busy in Italy, Muslim Saracens had set up a base near modern-day Saint-Tropez. From there, they raided Provence, attacking isolated villages and monasteries. They even raided as far as the Italian Riviera and the Alps.

Louis the Blind and Hugh of Italy tried to expel the Saracens but failed. In 973, the Saracens captured the abbot of Cluny monastery and held him for ransom. This angered Count William I, who organized an army. He defeated the Saracens at the Battle of Tourtour. The Saracens who were not killed were forced to convert or flee.

This victory became a famous event in Provence. William became known as "William the Liberator." He gave the lands taken from the Saracens to his followers. His family became the main leaders of Provence.

During these wars, trade was rare, and little new art or buildings were created. However, the Provençal language, based on Latin, developed during this time.

Catalan Dynasty and Growing Cities

In 1112, Douce I, Countess of Provence, married Ramon Berenguer III, Count of Barcelona. This brought Provence under the rule of the Catalan Dynasty, who ruled until 1246. In 1125, Provence was divided. The capital moved from Arles to Aix-en-Provence.

After the Crusades, international trade started again in Mediterranean ports and along the Rhône. Marseille's port became busy once more. Towns like Saint-Gilles, Tarascon, and Avignon became important trading centers.

During the 12th century, some cities in Provence gained a lot of freedom. They were ruled by elected officials called consuls. Marseille even created its own rules for justice and city management. Some Provençal cities made their own trade deals with Italian cities. However, the Counts of Provence later reduced the power of most of these city governments.

Cathedrals and Monasteries

The 12th century saw the building of beautiful new cathedrals and abbeys in Provence. This new style, called romanesque architecture, blended local Roman styles with styles from the Alps. Aix Cathedral was built on an old Roman site. The Church of St. Trophime in Arles is a famous example of Romanesque architecture. A large, fortress-like monastery, Montmajour Abbey, was built near Arles and became a popular place for medieval pilgrims.

Three Cistercian monasteries were built in remote areas of Provence: Sénanque Abbey (1148-1178), Le Thoronet Abbey (1160), and Silvacane Abbey (1175). These monasteries were far from city politics and focused on religious life.

Battles for Provence

In the early 13th century, a religious conflict in nearby Languedoc affected Provence. The Pope sent soldiers to fight the Cathar religious movement. This led to a war between French knights and the Counts of Toulouse, who had lands in Provence.

Soldiers from Provence joined the fight against the French. The French eventually captured Avignon. By a treaty in 1229, the part of Provence west of the Rhône became part of France.

Meanwhile, Ramon Berenguer IV ruled eastern Provence. He was the first Count to live permanently in Provence, usually in Aix. He worked to bring all the cities under his control.

Ramon Berenguer faced resistance from the Count of Toulouse, Raymond VII, who had lost land to France. Raymond VII allied with Marseille and Avignon against Ramon Berenguer. Ramon Berenguer strengthened his alliance with France, marrying his daughter Marguerite to King Louis IX of France. The French army helped Ramon Berenguer, and he gained control of most of Provence.

Ramon Berenguer had no sons, only four daughters. After his death in 1245, his youngest daughter, Beatrice, married Charles, Count of Anjou, the youngest son of the French king. This tied Provence even more closely to the French royal family.

Popes in Avignon

In 1309, Pope Clement V moved the Roman Catholic Papacy from Rome to Avignon. Seven Popes lived in Avignon until 1377. After that, there was a split in the Church, with rival popes in Rome and Avignon. Three more "antipopes" reigned in Avignon until 1423, when the Papacy finally returned to Rome. Between 1334 and 1363, the Popes built the Palais des Papes (Papal Palace) in Avignon, which is the largest gothic palace in Europe.

The 14th century was a difficult time for Provence. The Black Death (1348–1350) killed a huge number of people, cutting the population of cities like Arles in half. Wars also forced cities to build walls to defend themselves.

The rulers of Provence also faced challenges. Queen Joan I of Naples was murdered in 1382, leading to a new war. This resulted in Nice and some other areas separating from Provence in 1388 and joining the territories of Savoy.

Good King René: The Last Ruler

The 15th century brought more wars. In 1423, the King of Aragon captured Marseille. In 1443, he captured Naples, forcing its ruler, King René I of Naples, to flee. René eventually settled in Provence, one of his remaining lands.

History calls him "Good King René of Provence," even though he only lived there for the last ten years of his life (1470-1480). Provence grew economically during his rule. René was a generous supporter of the arts, helping painters like Nicolas Froment. He also finished building one of the finest castles in Provence, at Tarascon.

When René died in 1480, his title passed to his nephew. One year later, in 1481, the title went to Louis XI of France. In 1486, Provence officially became part of the French kingdom.

Provence Becomes French

Soon after joining France, Provence became involved in the French Wars of Religion in the 16th century. Many Jews were expelled from their homes and found safety in Avignon, which was still ruled by the Pope. In 1545, some villages in the Luberon were destroyed because their inhabitants were Waldensians, a group not considered Catholic enough. Most of Provence remained strongly Catholic.

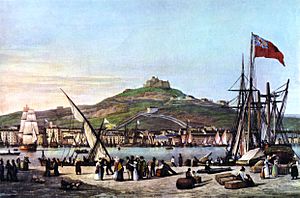

Some parts of Provence, especially Marseille, continued to rebel against the French king. After uprisings, King Louis XIV had two large forts built at Marseille's harbor to control the city.

In the early 17th century, a naval base and shipyard were built at Toulon for the French Mediterranean fleet. This base was greatly expanded later.

Provence was mostly rural, growing wheat, wine, and olives. It also had small industries like tanning and perfume-making. Cities like Marseille and Toulon saw new boulevards and fancy houses built.

In the early 18th century, Provence suffered from economic problems. The plague hit Marseille between 1720 and 1722, killing about 40,000 people. However, by the end of the century, many small industries began to thrive, like perfumes in Grasse and pottery in Marseille. Many immigrants came from Italy. By the late 18th century, Marseille was the third-largest city in France.

The French Revolution

Provence played a part in the French Revolution. Some important figures came from Provence, like Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau, who wanted France to become a constitutional monarchy.

Provence also gave the world La Marseillaise, France's national anthem. It was originally a war song written in 1792. It became famous when volunteers from Marseille sang it as they marched to Paris.

The Revolution was violent in Provence. In Marseille, a fort was attacked, and soldiers were killed. In Avignon, royalists were massacred. When radical revolutionaries took power, a counter-revolution broke out in Marseille and Toulon. A revolutionary army recaptured Marseille. In Toulon, opponents of the Revolution handed the city to the British and Spanish. A young artillery commander, Napoleon Bonaparte, helped defeat the British and drive them out in December 1793. Many royalists were killed.

After the radicals lost power, there was a "White Terror" against revolutionaries. Peace returned only when Napoleon came to power in 1795.

Provence Under Napoleon and Beyond

Napoleon restored power to the old noble families in Provence. The British fleet blocked Toulon, stopping almost all sea trade and causing poverty. When Napoleon was defeated, Provence celebrated. When he escaped from Elba in 1815, he avoided Provence because the people were against him.

Provence in the 19th Century

Provence became prosperous in the 19th century. The ports of Marseille and Toulon connected Provence to the growing French Empire in North Africa and the East, especially after the Suez Canal opened in 1869.

In 1860, Nice and its surrounding area, which had been separate for nearly 500 years, returned to France. This happened after France helped Italy in a war.

The railroad connected Paris to Marseille in 1848, and then to Toulon and Nice in 1864. Nice, Antibes, and Hyères became popular winter resorts for European royalty, including Queen Victoria. Marseille grew to a population of 250,000. Large cities built new churches, opera houses, and grand boulevards.

After the fall of Emperor Napoleon III, there were uprisings in Marseille in 1871, similar to the Paris Commune. The army crushed these uprisings.

The second half of the 19th century saw a revival of the Provençal language and culture. A group of writers and poets called the Félibrige, led by Frédéric Mistral, promoted traditional rural values. Mistral won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1904.

Provence in the 20th Century

Between World War I and World War II, Provence was divided between conservative rural areas and more radical cities. There were strikes in Marseille and riots in Toulon.

After France's defeat by Germany in June 1940, Provence was in the unoccupied zone. Parts of eastern Provence were occupied by Italian soldiers. Resistance against the Germans grew stronger, especially after Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Jean Moulin, a key leader of the French Resistance, parachuted into Provence in 1942 to unite the different resistance groups.

In November 1942, the Germans occupied all of Provence. The French fleet at Toulon sank its own ships to prevent them from falling into German hands. The Germans rounded up Jews and refugees, sending many to concentration camps. A large part of Marseille's port area was destroyed to prevent it from being used by the resistance.

On August 15, 1944, Allied forces landed on the Var coast (Operation Dragoon). American forces moved north, while French forces liberated towns like Brignoles, Salon, Arles, and Avignon. Toulon and Marseille were liberated by late August.

After the war, Provence faced a huge task of rebuilding. The first modern concrete apartment block, the Unité d'Habitation by Corbusier, was built in Marseille. In 1962, many French citizens from Algeria settled in Provence after Algeria gained independence. Large North African communities now live in and around major cities.

In the 1940s, Provence experienced a cultural rebirth with the founding of the Avignon Festival of theatre and the reopening of the Cannes Film Festival. New highways, like the Paris-Marseille autoroute (opened in 1970), made Provence a popular tourist destination. The TGV high-speed trains shortened the trip from Paris to Marseille to less than four hours.

At the end of the 20th century and into the 21st century, people in Provence have been working to balance economic growth and population increase with their desire to protect the unique landscape and culture of the region.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Provenza para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Provenza para niños

- Timeline of Provence

- Cities in Provence

- Timeline of Aix-en-Provence

- Timeline of Marseille

- Timeline of Toulon

- Castellane

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |