History of the horse in Britain facts for kids

The story of horses in Britain is a very long one! We know about it from horse bones found in places like Pakefield, Suffolk, which are 700,000 years old. Other bones from Boxgrove, West Sussex, are 500,000 years old. Early humans hunted horses for food during the Ice Age. Back then, Britain was connected to Europe by a land bridge called "Doggerland". This meant animals, including horses, could walk freely between the two areas.

People started taming horses in Britain around 2500 BC. They used them to pull carts and other vehicles. By the time the Romans invaded Britain, local tribes had huge armies with thousands of chariots! Over time, people worked to make horses better for different jobs. Kings like King John and Edward III brought in strong stallions from other countries. Laws were even made to control horse breeding and stop bad horses from being used.

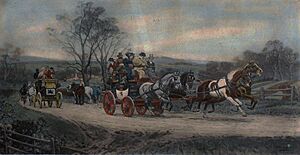

By the 1600s, different horse breeds were known for specific tasks. New farm machines were designed to be pulled by horses. Fast coaches, pulled by speedy Thoroughbred horses, used improved roads to travel quickly. But in the mid-1800s, steam power started replacing horses on farms. Horses were still used in wars for almost another 100 years because they were fast and could move easily over rough ground. By the 1980s, most working horses had disappeared from Britain. Today, horses in Britain are mostly kept for fun, like riding and sports.

Contents

Ancient Horses in Britain: The Ice Age

The very first horse remains found in Britain and Ireland are from a time called the Middle Pleistocene. Scientists found bones of two horse types at Pakefield, East Anglia, dating back 700,000 years. At Eartham Pit, Boxgrove, a horse shoulder bone from 500,000 BC showed spear marks. This means early humans were hunting horses there.

Britain was often connected to Europe by a land bridge. This bridge stretched from North Yorkshire to the English Channel. It allowed humans and animals, like horses, to move between these areas. As the climate changed, hunters followed their prey.

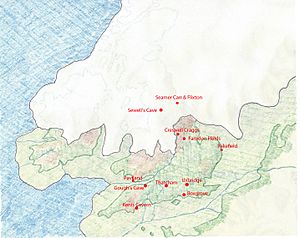

Even though much of ancient Britain is now under the sea, we've found many horse remains on land. For example, a horse tooth from 55,000 to 47,000 BC was found in Pin Hole Cave. More horse bones from the same time were found at Kent's Cavern. In Robin Hood Cave, also in Creswell Crags, a horse tooth from 32,000 to 24,000 BC was found. This cave also has one of Britain's oldest artworks: a horse carving on a horse bone! A small statue of a goddess, made from horse bone, was found in Paviland Cave in South Wales. It dates from about 23,000 BC.

Later Ice Age horse remains, from around 12,000 BC, were found in Nottinghamshire. At Mother Grundy's Parlour, horse bones show cut marks from hunting around 10,000 BC. A horse bone with cut marks from the same time was also found in Victoria Cave in North Yorkshire.

Horses After the Ice Age: The Holocene Period

The Holocene period began about 11,700 years ago and continues today. This is our current warm period. Horse remains from the Middle Stone Age, early in the Holocene, have been found in Britain. However, much of Mesolithic Britain is now under the North Sea and English Channel. Rivers and coastal erosion continue to uncover old evidence.

During the last Ice Age, northern Britain was covered by ice. Sea levels were much lower. What is now the North Sea and English Channel was a huge, flat area of tundra. Around 12,000 BC, this land stretched north to Scotland. In 1998, an archaeologist named B.J. Coles called this area "Doggerland". The River Thames flowed through it, joining the Rhine river. This formed a rich hunting, bird-watching, and fishing ground for people in Europe.

Horse remains from 10,500–8,000 BC have been found in places like Sewell's Cave and Thatcham. Remains from around 7,000 BC were found in Gough's Cave.

Even though there's a gap in horse remains between 7000 BC and 3500 BC, wild horses likely stayed in Britain after it became an island around 5,500 BC. Wild horse bones have been found in Neolithic tombs from about 3500 BC.

Taming Horses Before the Romans Arrived

Domesticated horses were in Britain by about 2000 BC, during the Bronze Age. Horse gear like snaffle bits, used to harness horses to vehicles, have been found. Bronze Age cart wheels were also discovered. These might have been pulled by horses or oxen. We don't have much proof of early Bronze Age horse riding. But by the late Bronze Age, horses were ridden in battles. Small, tamed ponies lived on Dartmoor by 1500 BC.

During the Iron Age, horse bones were found in special pits at a temple site near Cambridge. About twenty Iron Age chariot burials have been found. One famous burial was of a woman with a chariot at Wetwang Slack. Most chariots were taken apart before burial. But the Ferrybridge and Newbridge chariots were buried whole. The Newbridge burial dates from 520–370 BC.

By the end of the Iron Age, horses were widely used for travel and fighting. There was also a lot of trade. A large collection of horse gear was found in Somerset. A rare copper alloy cheekpiece for a horse's bit was found in St Ewe, Cornwall. The horse was very important in ancient Celtic religion and myths. This is shown by the Uffington White Horse hill figure in Oxfordshire.

Horses from Roman Britain to the Norman Conquest

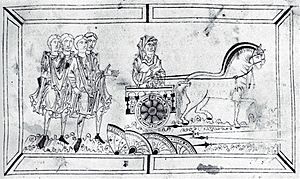

When Julius Caesar tried to invade Britain in 55 BC, the Britons were skilled horsemen. Caesar's soldiers faced British horsemen and war chariots. The chariots were even better than the Gaulish horsemen who came with Caesar. Later, Caesar fought against Cassivellaunus, who had over 4,000 war chariots. In other parts of Britain, the Romans met the "Gabrantovici," or "horse-riding warriors."

A lot of horse manure was found in a well at a Roman fort in Lancaster. This fort was a base for cavalry (soldiers on horseback). Bones of 28 horses were found in a Roman well at Dunstable, Bedfordshire. These horses were kept at a Roman stopping-station. Some were butchered for meat. But other horses were buried whole at Dunstable with special care. This might be linked to the Celtic goddess Epona, who protected horses. These burials show a belief that Epona protected the dead.

British horses were known for their quality even in Roman times. Many were taken to Italy to improve local horses there. Some of the earliest evidence of horse sports in Britain also comes from Roman times. A chariot-racing arena was found in Colchester, Essex.

From the 400s, horses were very important in Anglo-Saxon culture. Old English had many words for "horse." These words described horses for carts, pack horses, riding horses, and warhorses. Horses were mainly used for moving goods and people. Many English place names, like Stadhampton, refer to places where "studs," or herds, of horses were kept. Anglo-Saxon stirrups and spurs have been found. Horses were also raced for sport. A "race-course" in Kent is mentioned in a document from 949.

Sometimes, horses were eaten, maybe in very hard winters. But medieval writings show that Anglo-Saxons valued horses highly. Horses were often part of payments for land or gifts. Kings even had servants called horse-thegns, or marshals. The Domesday Book from 1086 recorded many horses and horse-breeding places. Six smiths in Hereford had to provide 120 horseshoes each year for warriors' horses.

Horses had religious meaning in Anglo-Saxon paganism. The historian Bede wrote that the first Anglo-Saxon leaders were Hengist and Horsa. These are Old English words for "stallion" and "horse." Scholars believe they were horse gods worshipped by pagans.

Horses also appear in stories about miracles in Anglo-Saxon Christianity. In the 600s, a horse supposedly found food for St Cuthbert. An angel on horseback helped him heal his knee. In the 700s, a horse's hooves reportedly revealed a spring of water for a monastery. In the 900s, King Edmund I was saved from falling off a cliff when his horse stopped. This happened after he prayed for forgiveness.

Vikings used horses for fast travel in Britain. They captured some horses and brought others with them. Horses were very important for Anglo-Saxon warfare. Armies traveled long distances. For example, King Penda of Mercia took his army far north to Bamburgh. Anglo-Saxon kings required many landowners to keep horses. In the 600s, an Anglo-Saxon warrior was buried with his horse at Sutton Hoo. Carvings on stone crosses show warriors on horseback. The Domesday Book recorded 62 "warhorses." In the 1000s, Anglo-Saxon horsemen fought successfully against Viking, Welsh, and Scottish armies.

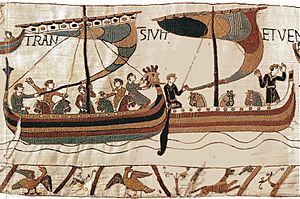

Duke William of Normandy brought horses across the English Channel for his invasion in 1066. The Battle of Hastings is often described as a victory for his cavalry. King Harold of England's army had just fought a battle in the north. His forces were smaller at Hastings. No English cavalry was used there.

The English troops at Hastings bravely faced four Norman cavalry charges. They only broke when their commanders were killed. The Norman mounted troops were called cavalry. But their weapons and armor were like foot soldiers. They didn't fight as an organized cavalry unit usually would.

Horses from Medieval Times to the Industrial Age

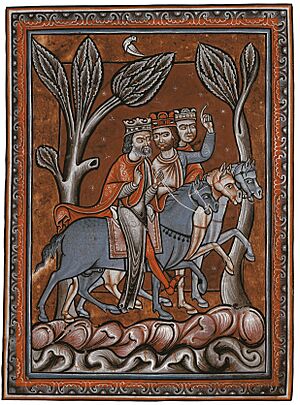

Improving horses for different jobs really took off during the Middle Ages. King Alexander I of Scotland brought two horses from the East to Britain. This was the first recorded import of oriental horses. King John (1199–1216) imported 100 strong Flemish stallions. He wanted to improve the "great horse" for tournaments and breeding. At the coronation of Edward I of England in 1274, royal guests gave away hundreds of their horses to anyone who could catch them!

King Edward III (1312–1377) imported 50 Spanish stallions. He also brought three "great horses" from France. He loved hunting, tournaments, and horse racing. Spanish horses were often used in races back then.

By the 1100s, many people owned horses. Farmers used horses to prepare land for crops. Horses and carts were increasingly used to move farm goods. Even poor farmers might have relied on one horse for all their work. Horse breeding continued to grow. In the 1300s, Hexham Priory had 80 broodmares. Other abbeys and nobles also owned horse farms.

Four-wheeled wagons were introduced in Britain by the early 1400s. This meant much heavier loads could be pulled. But it also meant horses needed to be stronger to pull these loads on bad roads. For very poor ground, pack horses were better than wagons. They were faster and could travel over rougher land. By this time, "post-horses" could be hired in towns along main routes. These were used by royal messengers.

In 1482, King Edward IV set up a temporary relay of riders between London and Berwick-upon-Tweed. Messages could be sent in two days. London merchants also set up a private horse system for mail to France in 1496. Henry VIII appointed the first British Master of the Post in 1512. He set up local postmasters whose boys would carry royal mail on horseback.

By the early 1500s, horses started replacing oxen for ploughing. Horses were faster, stronger, and more agile, especially on lighter soils. Oxen were still better on heavier soils because they pulled more steadily. The horse collar, which helps horses pull heavy loads, had been used in Europe for centuries. The use of horse teams in Britain was helped by more oats being farmed. Oats are a main food for hard-working horses.

During the Hundred Years' War (1300s-1400s), the English government banned horse exports. In the 1500s, Henry VII made laws to improve British horses. They had to be "kept within bounds." This led to many horses being gelded. In 1535, Henry VIII passed the Breed of Horses Act. It aimed to make horses taller and stronger. No stallion under 15 hands (152 cm) and no mare under 13 hands (132 cm) could run free on common land. Any small stallion or "unlikely" small horses were ordered to be destroyed. Henry VIII also started a stud farm to breed imported horses like Spanish Jennets and Flemish draught horses. However, this didn't have much effect. Later, in Queen Elizabeth I's reign, Nicholas Arnold was said to breed "the best horses in England."

During the reigns of queens Mary I and Elizabeth I, laws were made to stop horse theft. All horse sales had to be recorded. Laws about destroying small horses were partly removed by Elizabeth I in 1566. Some poor quality land couldn't support Henry VIII's desired large horses. This saved many of Britain's mountain and moorland pony breeds from being killed. As Britain's population grew, better transport was needed, increasing demand for good horses. Horse travel was so common that one morning, 2,200 horses were counted on the road between Shoreditch and Enfield.

During the Tudor and Stuart periods, more people owned horses in Britain than in Europe. But this declined in the late 1500s and early 1600s due to economic problems. When the economy recovered, horse ownership grew again. Travel became more popular. People often bought a horse for a journey and then sold it at their destination. Horse racing had been around for hundreds of years. But King James VI (1567–1625) brought the sport as we know it today from Scotland to England. He organized public races and imported quality animals to create a new, faster horse type.

When Gervase Markham published his book Cavalarice, or the English Horseman in 1617, farmers used many types of horses. They had pack horses, farm horses, and cart horses. They also bred horses for riding and driving. Markham suggested mixing native horses with other breeds for specific purposes. For example, he suggested Turks or Irish Hobbies for riding horses. He suggested Friesland and Flanders horses for light driving. He also suggested German heavy draught horses for heavy hauling. Horse fairs were common. Some of the first mentions of specific breeds, like Cleveland horses and Suffolk Punch horses, are from this time. Large Dutch horses were imported by King William III (1650–1702). He found that existing cart horses weren't strong enough to drain the Fens. These horses became known as Lincolnshire Blacks. Today's English heavy draught horses are their descendants. By the mid-1600s, British horses were famous in Europe. Sir Jonas Moore wrote in 1703 that Frenchmen offered three times the usual price for British horses.

During the reign of Charles I (1625–1649), people loved racing and fast hunting horses so much that there weren't enough heavy horses for tournaments and war. This caused problems because stronger horses were still needed. The English Civil War (1642–1651) stopped horse racing. Oliver Cromwell banned races and ordered racehorses to be seized. He focused on breeding cavalry horses by mixing light racing horses with heavier working horses. This created a new type of horse called the warmblood. Exporting any horse except geldings was forbidden. When the war ended, horse breeders faced hardship because demand for their horses dropped. But a secret trade in horses grew with wealthy Europeans. They wanted to buy the much-improved British horses. In 1656, laws on horse exports were finally removed. When the monarchy was restored in 1660, breeding quality horses started again "from scratch."

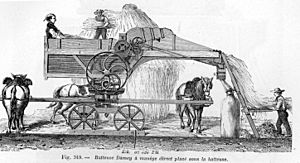

Horse-powered farm tools improved during this time. By 1600, a lighter plough called the "Dutch plough" was used in eastern England. It could be pulled by two horses. In 1730, the lightweight Rotherham plough was invented. It was said to reduce ploughing time by a third. The improved seed drill and horse-hoe were invented by Jethro Tull in 1731. But it took over 100 years for these designs to be widely used. The first horse-powered threshing machines were developed in the late 1700s.

Fast horse-drawn coaches, called 'Flying Coaches', started in 1669. A trip between London and Oxford used to take overnight. But Oxford University organized a project to complete the journey between sunrise and sunset. It worked, and Cambridge University quickly copied it. By 1685, Flying Coaches ran three times a week from London to all major towns. They could cover about fifty miles a day in good conditions. The Thoroughbred horse was developed around this time. Native mares were bred with Arab, Turk, and Barb horses to create excellent racehorses. The General Stud Book, which lists horse family trees, was first published in the 1790s. Today's Thoroughbred horses can be traced back to 1791. Horses in races sponsored by the monarchy carried heavy weights. This showed that horse racing and hunting also helped train horses for military use.

The Mail coach service began in the late 1700s, adding to the fast coach use. Horses for fast coaches were usually a mix of heavy farm mares and lighter racing horses. This gave them speed, agility, endurance, and strength. Rich people paid high prices for matching teams of quality horses. Farmers sold their best horses for good money. They kept lower-quality animals for themselves or sold them as saddle horses. The coaching business grew from carrying goods. Some public transport was provided by farmers. They could keep many horses cheaply on their farms. However, most of the trade was run by owners of coaching inns. Many inn owners only worked their horses locally. But some owned many inns and could provide transport over long distances. A benefit for inn owners was that coach passengers also used their inns, often staying overnight. Some inn owners had hundreds of horses.

Horses in the 1800s and 1900s

Horses were the main source of power for farming, mining, transport, and war until the steam engine arrived. The Middleton Railway was set up for industry in 1785. Parliament also allowed the building of the Surrey Iron Railway in 1801 and the Oystermouth Railway (later Swansea and Mumbles Railway) in 1804. These railways first used horse-drawn vehicles. But steam engines became cheaper and better for trains. The Swansea and Mumbles Railway was the first to carry paying passengers from 1807. Many others followed. By 1840, many railway lines were built. The number of rail miles grew from 1,497 in 1840 to 6,084 by 1850. Horse-drawn passenger coaches became almost useless for long journeys.

Steam engines also started replacing horses on farms. In 1849, Alderman Kell wrote that horses were very expensive compared to a steam engine, which "eats only when it works." Portable steam engines were invented in the 1840s. These allowed steam-powered machines to be used on small farms. One person could buy a portable machine and rent it out for haymaking and harvest. The only use for horses then was to move the machine. In the late Victorian era, Britain had about 3.3 million horses. In 1900, about a million were working horses. In 1914, 20,000 to 25,000 horses were used as cavalry in World War I.

Horses and ponies started working in British mines in the 1700s. They pulled coal and ore from the mine face to lifts or to the surface. Many of these were Shetlands because they were small but very strong. A stud farm just for breeding ponies for the pits was set up in 1870. The Shetland Pony Stud Book Society was formed in 1890 to stop the best stallions from being used in the pits. By 1984, only 55 pit ponies were still used in Britain. A horse named "Robbie," probably the last to work underground in a British coal mine, retired in May 1999.

In the First World War, horses were used in cavalry charges. They were also the best way to move scouts, messengers, supply wagons, ambulances, and artillery quickly. Horses could find their own food by grazing. They could also handle rough ground that machines couldn't. However, this war greatly harmed the British horse population. Thousands of animals were sent to war. Some breeds became so few in number that they were in danger of disappearing. Many breeds were saved by dedicated breeders who formed societies to track down and register the remaining animals.

Horses in the 21st Century

Working horses mostly disappeared from Britain's streets by the 2000s. A few exceptions are heavy horses pulling brewers' wagons, called drays. For example, when Young's Brewery stopped brewing in London in 2006, it ended over 300 years of using dray horses. Their team of Shire horses retired from delivery work. They now offer heavy horse team driving as a fun activity. They still appear at events for new Young's pubs. Other breweries, like Wadworth Brewery in Devizes, Wiltshire, still use Shire horses. But working teams are becoming very rare. In some areas, like the New Forest, farmers use horses to round up thousands of semi-feral ponies. Britain's mounted police use horses for crowd control. But apart from these special uses, horses in Britain today are almost entirely kept for fun. They compete in all equestrian sports. They carry riders on trekking and trail-riding holidays. They work in riding schools. They provide therapy for the disabled. And they are much-loved companions and hacks. British horses and riders have won many medals in equestrian sports at the Summer Olympic Games.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del caballo en Gran Bretaña para niños

In Spanish: Historia del caballo en Gran Bretaña para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |