Henry II of England facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Henry II |

|

|---|---|

Contemporary depiction of Henry from the Gospels of Henry the Lion, c. 1175–1188

|

|

| King of England (more...) | |

| Reign | 19 December 1154 – 6 July 1189 |

| Coronation | 19 December 1154 |

| Predecessor | Stephen |

| Successor | Richard I |

| Junior king | Henry (1170–1183) |

| Duke of Normandy | |

| Reign | 1150 – 6 July 1189 |

| Predecessor | Geoffrey Plantagenet |

| Successor | Richard I |

| Born | 5 March 1133 Le Mans, Maine, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 6 July 1189 (aged 56) Chinon Castle, Chinon, Touraine, Kingdom of France |

| Burial | Fontevraud Abbey, Anjou, France |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Plantagenet/Angevin |

| Father | Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou |

| Mother | Empress Matilda |

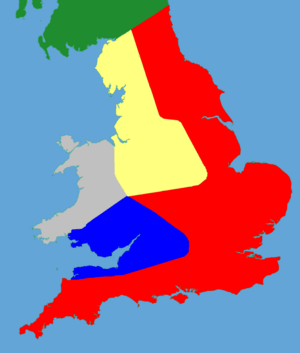

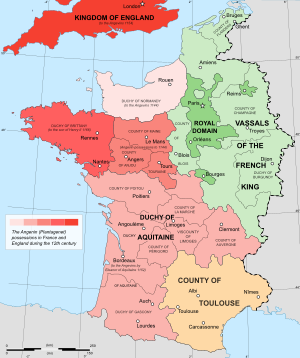

Henry II (born March 5, 1133 – died July 6, 1189) was the King of England from 1154 until his death. He was also known as Henry Curtmantle or Henry Plantagenet. During his rule, he controlled a huge area. This included England, parts of Wales, eastern Ireland, and a large part of western France. This area was later called the Angevin Empire. Henry also had a strong influence over Scotland and Brittany.

Henry became involved in politics at age 14. He helped his mother, Empress Matilda, try to claim the English throne. The throne was held by Stephen of Blois. In 1153, Stephen agreed to make Henry his heir. Henry became king when Stephen died a year later.

Henry was a very active and strong ruler. He wanted to bring back the royal lands and powers his grandfather, Henry I, had. Early in his reign, Henry fixed the royal government in England, which had almost fallen apart during Stephen's rule. He also took back control of Wales and his lands in France. Henry wanted to change the English Church. This led to a big conflict with his former friend, Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury. This argument lasted for many years and led to Becket's tragic death in 1170.

Henry also had conflicts with King Louis VII of France. They had a long "cold war" for decades. Henry made his empire bigger at Louis's expense. He took Brittany and moved into central and southern France. Even with many peace talks, they never reached a lasting agreement.

Henry and his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, had eight children. Eleanor brought control of the French Duchy of Aquitaine to Henry. Two of their sons became king. As his sons grew up, Henry found it hard to give them enough land and power. This caused tension, encouraged by Louis and his son King Philip II. In 1173, Henry's oldest son, "Young Henry," rebelled. His brothers Richard and Geoffrey joined him, as did their mother, Eleanor. Many European countries supported the rebels. Henry defeated this "Great Revolt" with strong military action.

Young Henry and Geoffrey rebelled again in 1183. Young Henry died during this time. The Norman invasion of Ireland gave lands for his youngest son, John. By 1189, Young Henry and Geoffrey were dead. Philip convinced Richard to join him, leading to a final rebellion. Henry was defeated by Philip and Richard. He was also very sick. Henry went to Chinon Castle in Anjou. He died soon after and Richard became king.

Henry's empire quickly fell apart when his son John became king in 1199. However, many of Henry's changes had long-lasting effects. His legal changes are seen as the basis for English Common Law. His actions in Brittany, Wales, and Scotland also shaped their societies and governments. Historians have seen Henry's reign in different ways over time. Many praised his achievements. Later, scholars looked at his personal life and the conflict with Becket. Today, historians combine British and French views to understand his rule.

Contents

Early Life (1133–1149)

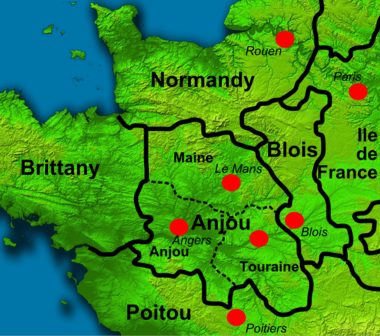

Henry was born in Maine, at Le Mans, on March 5, 1133. He was the first child of Empress Matilda and her second husband, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou. The French county of Anjou was created in the 900s. Its rulers, the Angevins, tried to expand their power in France. They did this through smart marriages and alliances. Anjou was supposed to answer to the French king. But the king's power over Anjou became weaker over time.

Henry's mother, Matilda, was the oldest daughter of Henry I, the King of England and Duke of Normandy. She came from a powerful Norman family. They owned large estates in both England and Normandy. Before he died, Henry I made his nobles promise to support Matilda's claim to the throne. This included his nephew, Stephen of Blois. After her father died in 1135, Matilda hoped to become queen. But Stephen was crowned king instead. This led to a civil war between their supporters, known as the Anarchy. Geoffrey, Henry's father, attacked Normandy. But he left the fight in England to Matilda and her half-brother, Robert, Earl of Gloucester. The war went on for a long time.

Henry likely spent his early years with his mother. He went with Matilda to Normandy in the late 1130s. From about age seven, Henry lived in Anjou. There, he was taught by Peter of Saintes, a famous grammarian. In 1142, Geoffrey sent nine-year-old Henry to Bristol. This city was a center for Matilda's supporters in England. Henry went with Robert of Gloucester, Matilda's powerful half-brother. It was common for noble children to be educated by relatives. Sending Henry to England also helped Geoffrey, who was criticized for not joining the war there.

For about a year, Henry lived with Robert's son, Roger of Worcester. He was taught by Master Matthew. Robert's household was known for its learning. The canons of St Augustine's in Bristol also helped Henry's education. He remembered them fondly later. Henry returned to Anjou in 1143 or 1144. He continued his education with William of Conches, another famous scholar.

Henry returned to England in 1147, when he was fourteen. He brought his household and some mercenaries. He landed in England and went into Wiltshire. His trip caused panic, but it did not succeed. Henry could not pay his soldiers and could not return to Normandy. His mother and uncle would not help him. Surprisingly, Henry asked King Stephen for help. Stephen paid Henry's soldiers, allowing him to leave. Stephen's reasons are not clear. He might have been polite to a family member. Or he might have wanted to end the war peacefully.

Henry tried again in 1149. This time, he planned to join forces with King David I of Scotland, his great-uncle. He also allied with Ranulf of Chester. Ranulf was a powerful leader in northwest England. They planned to attack York, possibly with Scottish help. But Stephen quickly marched north to York. Henry's plan fell apart, and he went back to Normandy.

Appearance and Personality

Chroniclers said Henry was good-looking. He had red hair, freckles, and a large head. His body was short and strong. He was bow-legged from riding horses. He often dressed simply. Henry was known for his energy and drive. He was strong-willed but not cruel. He was also famous for his intense stare, his forceful manner, and sudden bursts of anger. Sometimes, he would refuse to speak at all. Some of these outbursts might have been for show.

Henry was said to understand many languages, including English. But he only spoke Latin and French. When he was young, Henry loved fighting, hunting, and adventures. As he got older, he focused more on justice and government. He became more careful. But throughout his life, he was energetic and often acted on impulse. Despite his anger, he was usually not overly bossy. He was witty in conversation and good at arguments. He had an intellectual mind and an amazing memory. He preferred hunting or reading in his room to tournaments or music. Henry also cared for ordinary people. Early in his reign, he ordered that shipwrecked people should be treated well. He set harsh punishments for anyone who stole their goods. When a famine hit Anjou and Maine in 1176, Henry used his own food stores to help the poor.

Henry strongly wanted to regain control of the lands his grandfather, Henry I, once ruled. His mother, Matilda, likely influenced him. She also had a strong sense of old rights and powers. Henry took back lands, regained estates, and brought smaller lords back under his influence. These lords had once formed a "protective ring" around his main territories. He was probably the first English king to use a heraldic design. This was a signet ring with a leopard or lion on it. This design later became the Royal Arms of England.

Early Reign (1150–1162)

Gaining Lands in France

By the late 1140s, the civil war in England was mostly over. Many nobles were making their own peace deals. The English church also seemed to want a peace treaty. When Louis VII returned from the Second Crusade in 1149, he worried about Geoffrey's growing power. He was especially concerned if Henry became King of England. In 1150, Geoffrey made Henry the Duke of Normandy. Louis reacted by supporting Stephen's son, Eustace, as the rightful duke. Louis launched a military campaign to remove Henry from Normandy. Henry's father told him to make peace with Louis. They made peace in August 1151. Henry gave homage to Louis for Normandy, accepting Louis as his lord. He also gave Louis the disputed lands of the Norman Vexin. In return, Louis recognized Henry as duke.

Geoffrey died in September 1151. Henry delayed his return to England. He first needed to secure his lands, especially Anjou. Around this time, he was also planning his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. Eleanor was the Duchess of Aquitaine, a land in southern France. She was known for being beautiful and lively. She had been married to Louis but had not had any sons. Louis had their marriage ended. Eight weeks later, on May 18, the nineteen-year-old Henry married Eleanor, who was eleven years older.

This marriage immediately caused new tensions with Louis. It was seen as an insult. It also went against feudal rules because Eleanor married without Louis's permission. Also, Henry and Eleanor were related, just as she and Louis had been. Henry gaining Aquitaine also threatened the inheritance of Louis and Eleanor's two daughters. With his new lands, Henry now controlled much more of France than Louis. Louis formed an alliance against Henry. This included Stephen, Eustace, Henry I, Count of Champagne, and Robert, Count of Perche. Henry's younger brother, Geoffrey, also joined Louis. Geoffrey rebelled, saying Henry had taken his inheritance. Their father's plans for his lands were unclear.

Fighting started again along the Normandy borders. Henry of Champagne and Robert captured Neufmarché-sur-Epte. Louis's forces attacked Aquitaine. Stephen besieged Wallingford Castle, a key fortress loyal to Henry in England. He hoped to end the English conflict while Henry was busy in France. Henry moved quickly. He avoided open battle with Louis in Aquitaine. He stabilized the Norman border, raiding the Vexin. Then he attacked south into Anjou against Geoffrey, capturing Montsoreau Castle. Louis became sick and left the campaign. Geoffrey was forced to make peace with Henry.

Becoming King of England

In response to Stephen's siege, Henry returned to England in early 1153. He brought a small army of mercenaries. He was supported by Ranulf of Chester and Hugh Bigod in northern and eastern England. He hoped for a military victory. A group of senior English church leaders met with Henry in April. They wanted a peaceful end to the war. Henry promised to avoid attacking English cathedrals.

To draw Stephen's forces away from Wallingford, Henry besieged Stephen's castle at Malmesbury. Stephen marched west with an army to help it. Henry avoided Stephen's larger army along the River Avon. He prevented Stephen from forcing a big battle. As winter approached, they agreed to a temporary truce. Henry then traveled north through the Midlands. There, the powerful Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, supported him. Henry then turned his forces south against the besiegers at Wallingford. He and his allies now controlled the southwest, Midlands, and much of northern England. Henry tried to act like a legitimate king. He witnessed marriages and held court.

Over the next summer, Stephen gathered troops to besiege Wallingford Castle again. The castle seemed about to fall. Henry marched south to help, arriving with a small army. He then besieged Stephen's forces. When Stephen heard this, he returned with a large army. The two sides faced each other across the River Thames at Wallingford in July. By this point, nobles on both sides wanted to avoid a big battle. So, church leaders arranged a truce. Henry and Stephen spoke privately about ending the war. Luckily for Henry, Stephen's son Eustace became sick and died soon after. This removed the main rival for the throne. Stephen had another son, William, but he was not interested in becoming king. Fighting continued after Wallingford, but not with full effort. The English Church tried to make a lasting peace.

In November, the two leaders agreed to a permanent peace. Stephen announced the Treaty of Winchester in Winchester Cathedral. He recognized Henry as his adopted son and successor. In return, Henry gave homage to Stephen. Stephen promised to listen to Henry's advice but kept his royal powers. Stephen's son William would give homage to Henry and give up his claim to the throne. In exchange, his lands would be safe. Key royal castles would be held for Henry. Stephen would have access to Henry's castles. Foreign soldiers would be sent home. Henry and Stephen sealed the treaty with a kiss of peace in the cathedral.

The peace was fragile. Stephen's son William remained a possible rival. Rumors of a plot to kill Henry spread. Henry decided to return to Normandy for a while. Stephen became sick with a stomach disorder and died on October 25, 1154. This allowed Henry to become king sooner than expected.

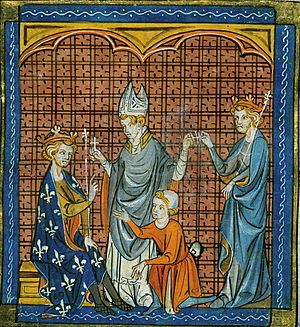

Rebuilding Royal Government

Henry landed in England on December 8, 1154. He quickly received loyalty oaths from some nobles. He was crowned with Eleanor at Westminster Abbey on December 19. The royal court met in April 1155. There, the nobles swore loyalty to the King and his sons. Several potential rivals still existed, including Stephen's son William and Henry's brothers Geoffrey and William. But they all died in the next few years, making Henry's position secure.

Henry faced a difficult situation in England. The kingdom had suffered greatly during the civil war. Many areas were devastated. Many "unauthorized" castles had been built by local lords. The royal forest law had broken down. The King's income had dropped a lot. Royal control over the coin mints was limited.

Henry presented himself as the rightful heir to Henry I. He began rebuilding the kingdom. Stephen had tried to continue Henry I's government. But Henry's new government described Stephen's nineteen years as chaotic. Henry was also careful to show that he would listen to advice, unlike his mother. Several actions were taken right away. Henry spent six and a half years out of his first eight years in France. So, much work was done from a distance. The unauthorized castles from the war were torn down. Efforts were made to restore royal justice and finances. Henry also spent a lot on building and fixing royal buildings.

The King of Scotland and Welsh rulers had taken advantage of the civil war. They seized disputed lands. Henry worked to get these lands back. In 1157, Henry pressured King Malcolm of Scotland to return lands in northern England. Henry then refortified the northern border. Restoring Anglo-Norman power in Wales was harder. Henry had to fight two campaigns in north and south Wales in 1157 and 1158. After this, the Welsh princes Owain Gwynedd and Rhys ap Gruffydd submitted to his rule. They agreed to the borders that existed before the civil war.

Campaigns in France

Henry had problems with Louis VII of France throughout the 1150s. They had already clashed over Henry becoming Duke of Normandy and Eleanor's remarriage. Louis always tried to seem morally superior to Henry. He used his reputation as a crusader and spread rumors about Henry. Henry had more resources than Louis, especially after taking England. Louis was less active in fighting Angevin power than he had been earlier. The disputes between them involved other powers. Thierry, Count of Flanders, signed a military alliance with Henry. Further south, Theobald V, Count of Blois, an enemy of Louis, became Henry's ally. The military tensions and frequent meetings to solve them were like the Cold War in the 20th century.

When Henry returned to France from England, he wanted to secure his French lands. He also wanted to stop any rebellions. In 1154, Henry and Louis agreed to a peace treaty. Henry bought back the Vernon and the Neuf-Marché from Louis. The treaty seemed unstable, and tensions remained. Henry had not given homage to Louis for his French lands. They met in Paris and Mont-Saint-Michel in 1158. They agreed to marry Henry's oldest living son, Young Henry, to Louis's daughter Margaret. This marriage deal would give Henry the disputed Vexin region. This would eventually give Henry the lands he wanted. But it also suggested that the Vexin belonged to Louis to give away, which was a political win for Louis. For a short time, a lasting peace between Henry and Louis seemed possible.

Meanwhile, Henry started to change his policy in the Duchy of Brittany. He began to take more direct control. Brittany was next to his lands and was usually independent. In 1164, Henry took lands along the border of Brittany and Normandy. In 1166, he invaded Brittany to punish local nobles. Henry then forced Duke Conan III to step down. He gave Brittany to Conan's daughter Constance. Constance was given to Henry and engaged to his son Geoffrey. This was unusual because Conan might have had sons who could have inherited the duchy. Elsewhere in France, Henry tried to seize the Auvergne. This angered the French king. Further south, Henry continued to pressure Raymond of Toulouse. Henry campaigned there in 1161. He sent the Archbishop of Bordeaux against Raymond in 1164. He also encouraged Alfonso II of Aragon in his attacks. In 1165, Raymond divorced Louis's sister and tried to ally with Henry.

These growing tensions between Henry and Louis led to open war in 1167. It started over a small argument about collecting money for the Crusader states in the Levant. Louis allied with the Welsh, Scots, and Bretons. He attacked Normandy. Henry responded by attacking Chaumont-sur-Epte, where Louis kept his main military supplies. He burned the town. This forced Louis to leave his allies and make a private truce. Henry was then free to move against the rebellious nobles in Brittany.

As the decade went on, Henry wanted to settle the issue of who would inherit his lands. He decided to divide his empire after his death. Young Henry would get England and Normandy. Richard would get the Duchy of Aquitaine. Geoffrey would get Brittany. This needed Louis's approval. So, the kings held new peace talks in 1169 at Montmirail. The talks were broad. Henry's sons gave homage to Louis for their future lands in France. Richard was also engaged to Louis's young daughter Alys.

If the agreements at Montmirail had been followed, they could have confirmed Louis's position as king. They also could have weakened any rebellious nobles in Henry's lands. But Louis felt he had gained an advantage. He immediately started to encourage tensions between Henry's sons. Meanwhile, Henry's position in southern France continued to improve. By 1173, he allied with Humbert III, Count of Savoy. This engaged Henry's son John to Humbert's daughter Alicia. Henry's daughter Eleanor married Alfonso VIII of Castile in 1170. This brought another ally in the south. In February 1173, Raymond finally gave homage for Toulouse to Henry and his heirs.

Intervention in Ireland

In the mid-1100s, Ireland was ruled by local kings. Their power was more limited than rulers in other parts of western Europe. In the 1160s, the King of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, was removed from power by the High King of Ireland, Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair. Diarmait asked Henry for help in 1167. Henry allowed Diarmait to hire soldiers from his empire. Diarmait gathered Anglo-Norman and Flemish soldiers from the Welsh Marches. This included Richard de Clare, Earl of Pembroke. With his new supporters, he took back Leinster. But he died soon after in 1171. De Clare then claimed Leinster for himself. The situation in Ireland was tense. The Anglo-Normans were greatly outnumbered.

Henry saw this as a chance to get involved in Ireland himself. He took a large army into south Wales. He forced the rebels there to surrender. Then he sailed from Pembroke, Pembrokeshire, and landed in Ireland in October 1171. Some Irish lords asked Henry to protect them from the Anglo-Norman invaders. De Clare offered to submit to Henry if he could keep his new lands. Henry's timing was influenced by several things. Pope Alexander encouraged him, seeing a chance to establish papal power over the Irish church. But the main reason seemed to be Henry's worry. He feared his nobles in Wales would gain independent lands in Ireland, beyond his control. Henry's intervention worked. Both the Irish and Anglo-Normans in southern and eastern Ireland accepted his rule.

Henry started building many castles during his visit in 1171. This was to protect his new territories. The Anglo-Normans had better military technology than the Irish. Castles gave them a big advantage. Henry hoped for a long-term political solution, like his approach in Wales and Scotland. In 1175, he agreed to the Treaty of Windsor. Under this treaty, Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair would be recognized as the High King of Ireland. He would give homage to Henry and keep peace on the ground for him. This policy did not work. Ua Conchobair could not control areas like Munster. So, Henry got more directly involved. He set up a system of local fiefs through a meeting in Oxford in 1177.

The Great Revolt (1173–1174)

In 1173, Henry faced the Great Revolt. This was an uprising by his oldest sons and rebellious nobles. France, Scotland, and Flanders supported them. Several reasons caused the revolt. Young Henry was unhappy. Even though he was called king, he made no real decisions. His father also kept him short of money. He had been close to Thomas Becket, his former teacher. He might have blamed his father for Becket's death. Geoffrey faced similar problems. Duke Conan of Brittany died in 1171. But Geoffrey and Constance were still unmarried. This left Geoffrey without his own lands. Richard was encouraged to join the revolt by Eleanor. Her relationship with Henry had broken down. Local nobles, unhappy with Henry's rule, saw a chance to regain power by allying with his sons.

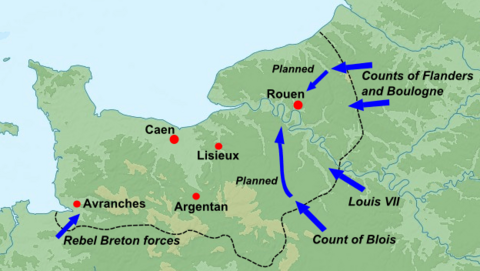

The final trigger was Henry's decision to give his youngest son John three important castles that belonged to Young Henry. Young Henry protested, then fled to Paris. His brothers Richard and Geoffrey followed him. Eleanor tried to join them but was captured by Henry's forces in November. Louis supported Young Henry, and war was about to begin. Young Henry wrote to the pope, complaining about his father. He started gaining allies, including King William of Scotland and the Counts of Boulogne, Flanders, and Blois. All were promised lands if Young Henry won. Major noble revolts broke out in England, Brittany, Maine, Poitou, and Angoulême. In Normandy, some border nobles rebelled. Most of the duchy stayed loyal, but there was general unhappiness. Only Anjou remained fairly secure. Despite the large crisis, Henry had advantages. He controlled many strong royal castles in key areas. He controlled most English ports. He was still popular in towns across his empire.

In May 1173, Louis and Young Henry tested the defenses of the Vexin. This was the main route to Rouen, the Norman capital. Armies invaded from Flanders and Blois, trying to attack from two sides. Rebels from Brittany invaded from the west. Henry secretly went back to England to order an attack on the rebels there. When he returned, he counter-attacked Louis's army. He defeated many of them and pushed them back across the border. An army was sent to push back the Brittany rebels. Henry then pursued, surprised, and captured them. Henry offered to negotiate with his sons. But these talks at Gisors soon failed. Meanwhile, the fighting in England was balanced. Then a royal army defeated a larger force of rebel and Flemish soldiers in September. This was at the Battle of Fornham near Fornham All Saints in Suffolk. Henry used this break to crush rebel strongholds in Touraine. This secured the important route through his empire. In January 1174, Young Henry and Louis attacked again. They threatened to push into central Normandy. The attack failed, and fighting stopped for the winter.

In early 1174, Henry's enemies seemed to try to lure him back to England. This would let them attack Normandy in his absence. As part of this plan, William of Scotland attacked southern England. Northern English rebels supported him. More Scottish forces went into the Midlands, where rebel nobles were doing well. Henry did not fall for the trap. Instead, he focused on crushing opposition in southwest France. William's campaign began to fail. The Scots could not take the key northern royal castles. This was partly due to Henry's illegitimate son, Geoffrey. To restart the plan, Philip, the Count of Flanders, announced he would invade England. He sent an advance force into East Anglia. The possible Flemish invasion forced Henry to return to England in early July. Louis and Philip could now move overland into eastern Normandy and reached Rouen.

Henry traveled to Becket's tomb in Canterbury. He said the rebellion was a divine punishment on him. He performed penance. This greatly helped restore his royal authority at a critical time. Then Henry heard that King William had been defeated and captured. This happened at Alnwick in Northumberland, by local forces. This crushed the rebel cause in the north. The remaining English rebel strongholds collapsed. In August, Henry returned to Normandy. Louis had not yet taken Rouen. Henry's forces attacked the French army just before their final assault on the city began. Pushed back into France, Louis asked for peace talks. This ended the conflict.

Final Years (1175–1189)

After the Great Revolt

After the Great Revolt, Henry held talks at Montlouis. He offered a mild peace based on how things were before the war. Henry and Young Henry promised not to seek revenge on each other's followers. Young Henry agreed to give the disputed castles to John. In return, the elder Henry gave Young Henry two castles in Normandy and 15,000 Angevin pounds. Richard and Geoffrey received half the income from Aquitaine and Brittany, respectively. Eleanor was kept under house arrest until the 1180s. The rebellious nobles were imprisoned for a short time and sometimes fined. Then they got their lands back. Rebel castles in England and Aquitaine were destroyed.

Henry was less generous to William of Scotland. William was not released until he agreed to the Treaty of Falaise in December 1174. Under this treaty, he publicly gave homage to Henry. He also gave five key Scottish castles to Henry's men. Philip of Flanders declared he would be neutral towards Henry. In return, Henry agreed to give him regular financial support.

Henry now seemed stronger than ever to people at the time. Many European leaders sought him as an ally. They asked him to settle international disputes in Spain and Germany. But he was busy fixing weaknesses that he believed made the revolt worse. Henry expanded royal justice in England to strengthen his power. He spent time in Normandy building support among the nobles. The King also used the growing popularity of Becket to increase his own prestige. He said the saint's power explained his victory in 1174, especially capturing William.

The 1174 peace did not solve the long-standing tensions between Henry and Louis. These tensions reappeared in the late 1170s. The two kings began to compete for control of Berry. This was a rich region important to both kings. Henry had some rights to western Berry. But in 1176, he made an unusual claim. He said he had agreed in 1169 to give Richard's fiancée Alys the whole province. If Louis accepted this, it would mean Berry was Henry's to give away. This would give Henry the right to occupy it for Richard. To pressure Louis, Henry prepared his armies for war. The pope intervened. As Henry likely planned, the two kings were encouraged to sign a non-aggression treaty in September 1177. They promised to go on a joint crusade. The ownership of Auvergne and parts of Berry was decided by a panel. The panel ruled in Henry's favor. Henry then bought La Marche from the local count. This expansion of Henry's empire again threatened French security. It quickly put the new peace at risk.

Family Tensions

In the late 1170s, Henry focused on creating a stable government. He increasingly ruled through his family. But tensions over who would inherit his lands were always present. This eventually led to a new revolt. After putting down the remaining rebels from the Great Revolt, Henry recognized Richard as the Duke of Aquitaine in 1179. In 1181, Geoffrey finally married Constance of Brittany and became Duke of Brittany. By then, most of Brittany accepted Angevin rule. Geoffrey could handle the remaining problems on his own. John had traveled with his father during the Great Revolt. Most people now saw John as Henry's favorite child. Henry began to give John more lands, often at other nobles' expense. In 1177, he made John the Lord of Ireland. Meanwhile, Young Henry spent the end of the decade traveling in Europe. He took part in tournaments and played only a small role in government or military campaigns. He was increasingly unhappy with his position and lack of power.

By 1182, Young Henry repeated his earlier demands. He wanted lands, like the Duchy of Normandy. This would allow him to support himself and his household with dignity. Henry refused but agreed to increase his son's allowance. This was not enough for Young Henry. With trouble brewing, Henry tried to calm things. He insisted that Richard and Geoffrey give homage to Young Henry for their lands. Richard did not believe Young Henry had any claim over Aquitaine and refused. Henry forced Richard to give homage. But Young Henry angrily refused to accept it. He allied with some unhappy nobles in Aquitaine who disliked Richard's rule. Geoffrey sided with him. He raised an army in Brittany to threaten Poitou. Open war broke out in 1183. Henry and Richard led a joint campaign into Aquitaine. Before they could finish, Young Henry caught a fever and died. This brought a sudden end to the rebellion.

With his oldest son dead, Henry changed his plans for who would inherit. Richard was to be made King of England. But he would have no real power until his father died. Geoffrey had to keep Brittany, as he held it through marriage. So, Henry's favorite son John would become the Duke of Aquitaine instead of Richard. Richard refused to give up Aquitaine. He loved the duchy. He did not want to trade this role for the meaningless one of being the junior King of England. Henry was furious. He ordered John and Geoffrey to march south and take back the duchy by force. The short war ended in a stalemate. There was a tense family reconciliation in Westminster, England, at the end of 1184. Henry finally got his way in early 1185. He brought Eleanor to Normandy to tell Richard to obey his father. At the same time, he threatened to give Normandy, and possibly England, to Geoffrey. This was enough. Richard finally handed over the ducal castles in Aquitaine to Henry.

Meanwhile, John's first expedition to Ireland in 1185 was not successful. Ireland had only recently been conquered by Anglo-Norman forces. Tensions were high between Henry's representatives, the new settlers, and the existing inhabitants. John offended the local Irish rulers. He failed to make allies among the Anglo-Norman settlers. He began to lose ground militarily against the Irish. Finally, he returned to England. In 1186, Henry was about to send John back to Ireland. Then news came that Geoffrey had died in a tournament in Paris. He left two young children. This event again changed the balance of power between Henry and his remaining sons.

Henry and Philip Augustus

Henry's relationship with his two remaining sons was difficult. The King loved his youngest son John very much. But he showed little affection for Richard. He seemed to hold a grudge against him after their argument in 1184. The arguments and growing tensions between Henry and Richard were cleverly used by the new French King, Philip II Augustus. Philip came to power in 1180. He quickly showed he was a strong, calculating, and clever political leader.

At first, Henry and Philip Augustus had a good relationship. Despite attempts to divide them, Henry and Philip Augustus agreed to an alliance. This cost the French King the support of Flanders and Champagne. Philip Augustus saw Geoffrey as a close friend. He would have welcomed him as Henry's successor. With Geoffrey's death, the relationship between Henry and Philip broke down.

In 1186, Philip Augustus demanded custody of Geoffrey's children and Brittany. He insisted that Henry order Richard to leave Toulouse. Richard had been sent there with an army to pressure Philip's uncle, Raymond. Philip threatened to invade Normandy if this did not happen. He also brought up the Vexin issue again. This region was part of Margaret's dowry years before. Henry still occupied the region. Now Philip insisted that Henry either complete the long-agreed Richard-Alys marriage or return Margaret's dowry. Philip invaded Berry. Henry gathered a large army. They faced the French at Châteauroux. Papal intervention then brought a truce. During the talks, Philip suggested to Richard that they should ally against Henry. This marked the start of a new plan to divide the father and son.

Philip's offer came during a crisis in the Levant. In 1187, Jerusalem surrendered to Saladin. Calls for a new crusade spread across Europe. Richard was excited and announced he would join the crusade. Henry and Philip announced their similar intent in early 1188. Taxes were raised, and plans were made for supplies and transport. Richard was eager to start his crusade. But he had to wait for Henry to make his arrangements. Meanwhile, Richard crushed some of his enemies in Aquitaine in 1188. Then he attacked the Count of Toulouse again. Richard's campaign broke the truce between Henry and Philip. Both sides again gathered large forces for war. This time, Henry refused Philip's offers for a short truce. He hoped to convince the French King to agree to a long-term peace deal. Philip refused Henry's ideas. A furious Richard believed Henry was delaying and holding up the crusade.

Death of a King

The relationship between Henry and Richard finally became violent just before Henry's death. Philip held a peace meeting in November 1188. He publicly offered a generous, long-term peace settlement with Henry. He would agree to Henry's land demands. But only if Henry would finally marry Richard and Alys. And if he would announce Richard as his recognized heir. Henry refused. Richard then spoke up himself. He demanded to be recognized as Henry's successor. Henry stayed silent. Richard then publicly changed sides at the meeting. He gave formal homage to Philip in front of all the nobles.

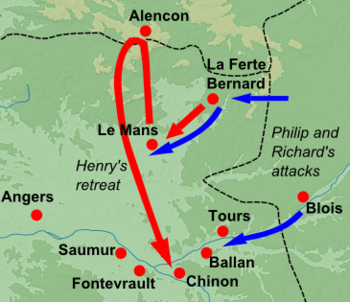

The pope intervened again to try to make a last-minute peace deal. This led to a new meeting at La Ferté-Bernard in 1189. By now, Henry was suffering from a bleeding ulcer. This sickness eventually killed him. The discussions achieved little. Henry is said to have offered Philip that John, not Richard, could marry Alys. This reflected rumors that Henry was thinking of openly disinheriting Richard. The meeting ended with war seeming likely. But Philip and Richard launched a surprise attack right after, during what was usually a truce.

Henry was caught by surprise at Le Mans. But he made a fast march north to Alençon. From there, he could escape to safety in Normandy. Suddenly, Henry turned back south towards Anjou. This was against his officials' advice. The weather was very hot. The King was getting sicker. He seemed to want to die peacefully in Anjou rather than fight another campaign. Henry avoided the enemy forces on his way south. He collapsed in his castle at Chinon. Philip and Richard were making good progress. It was clear Henry was dying and Richard would be the next king. The two offered negotiations. They met at Ballan. Henry, barely able to stay on his horse, agreed to surrender completely. He would pay homage to Philip. He would give Alys to a guardian, and she would marry Richard after the coming crusade. He would recognize Richard as his heir. He would pay Philip compensation. Key castles would be given to Philip as a guarantee. Henry had been defeated and forced to negotiate. But the terms were not extreme. Nothing much changed from Henry's surrender, except the humiliation of a dying man.

Henry was carried back to Chinon on a litter. There, he was told that John had publicly sided with Richard in the conflict. This betrayal was the final shock. The King finally collapsed into a fever. He regained consciousness only for a few moments. During this time, he made a religious confession. He died on July 6, 1189, at age 56. He had wanted to be buried at Grandmont Abbey in the Limousin. But the hot weather made moving his body difficult. So, he was buried at the nearby Fontevraud Abbey.

Henry's Legacy

Right after Henry's death, Richard successfully claimed his father's lands. He later left on the Third Crusade. But he never married Alys as he had agreed with Philip Augustus. Eleanor was released from house arrest. She regained control of Aquitaine, where she ruled for Richard. Henry's empire did not last long. It fell apart during the reign of his youngest son John. Philip captured almost all of Henry's lands in France, except Gascony. This collapse had many reasons. These included long-term changes in money and trade. Also, there were growing cultural differences between England and Normandy. But especially, Henry's empire was fragile because it was based on family connections.

Henry was often criticized by people living at his time, even in his own court. Despite this, Gerald of Wales, a writer who usually did not like the Angevins, wrote nicely about Henry. He called Henry "our Alexander of the West." He said Henry "extended your [Henry] hand from the Pyrenees to the westernmost limits of the Ocean." William of Newburgh, writing in the next generation, said that "the experience of present evils has revived the memory of his good deeds." He added that "the man who in his own time was hated by all men, is now declared to have been an excellent and beneficent prince."

Many of the changes Henry made during his long rule had big, lasting effects. His legal changes are generally seen as the foundation for English Common Law. The Exchequer court was an early version of the later Common Bench at Westminster. Henry's traveling judges also influenced legal changes by other rulers. For example, Philip Augustus's creation of traveling bailli clearly copied Henry's model. Henry's actions in Brittany, Wales, and Scotland also had a big, long-term impact. They shaped how those societies and governments developed.

How Historians See Henry

Henry and his reign have interested historians for many years. A detailed book by W. L. Warren says Henry was a genius at good, efficient government. In the 1700s, historian David Hume said Henry's reign was key to creating a truly English monarchy. And eventually, a united Britain. Hume called Henry "the greatest prince of his time for wisdom, virtue, and abilities." He also said Henry was "the most powerful in extent of dominion of all those who had ever filled the throne of England." Henry's role in the Becket conflict was seen as good by Protestant historians then. His arguments with the French King, Louis, also got positive, patriotic comments.

In the Victorian period, people became interested in the personal behavior of historical figures. Scholars started to worry more about parts of Henry's behavior. This included how he acted as a parent and husband. The King's role in Becket's death received special criticism. Late-Victorian historians had more access to old documents. They emphasized Henry's role in developing key English institutions. This included the law and the exchequer. William Stubbs' analysis led him to call Henry a "legislator king." He said Henry was responsible for major, lasting reforms in England. Influenced by the growing British Empire, historians like Kate Norgate researched Henry's lands in Europe. She created the term "the Angevin Empire" in the 1880s.

Historians in the 1900s questioned many of these ideas. In the 1950s, Jacques Boussard and John Jolliffe, among others, looked at Henry's "empire." French scholars especially studied how royal power worked during this time. The English-focused views of many Henry histories were challenged from the 1980s onward. Efforts were made to combine British and French historical analysis. More detailed study of Henry's written records has raised doubts about some earlier ideas. For example, Robert Eyton's 1878 work traced Henry's travels using financial records. But this method has been criticized as not always accurate for determining location or court attendance. Many more of Henry's royal charters have been found. But understanding these records, financial information, and wider economic data is harder than once thought. Big gaps in historical analysis of Henry remain. Especially about his rule in Anjou and southern France.

Still, Henry has generally received praise from popular historians in the 20th century. The Canadian-American historian and medievalist Norman Cantor called Henry a "remarkable man." He said Henry was "undoubtedly the greatest of all Medieval English kings." Winston Churchill said Henry had vision and ability. He called him England’s first great lawgiver. Churchill noted Henry left a uniquely deep mark on English institutions. He said Henry's instinct for government and law created the English Common Law. This is seen as his greatest achievement.

Genealogical table

: Bold borders indicate legitimate children of English monarchs

| Baldwin II King of Jerusalem |

Fulk IV Count of Anjou |

Bertrade of Montfort | Philip I King of France |

William the Conqueror King of England r. 1066–1087 |

Saint Margaret of Scotland | Malcolm III King of Scotland |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melisende Queen of Jerusalem |

Fulk V King of Jerusalem |

Eremburga of Maine | Robert Curthose | William II King of England r. 1087–1100 |

Adela of Normandy | Henry I King of England r. 1100–1135 |

Matilda of Scotland | Duncan II King of Scotland |

Edgar King of Scotland |

Alexander I King of Scotland |

David I King of Scotland |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sibylla of Anjou | William Clito | Stephen King of England r. 1135–1154 |

Geoffrey Plantagenet Count of Anjou |

Empress Matilda | William Adelin | Matilda of Anjou | Henry of Scotland |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Margaret I | Philip of Alsace Count of Flanders |

Louis VII King of France |

Eleanor of Aquitaine | Henry II King of England r. 1154–1189 |

Geoffrey Count of Nantes |

William FitzEmpress | Malcolm IV King of Scotland |

William the Lion King of Scotland |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baldwin I Latin Emperor |

Isabella of Hainault | Philip II King of France |

Henry the Young King | Matilda Duchess of Saxony |

Richard I King of England r. 1189–1199 |

Geoffrey II Duke of Brittany |

Eleanor | Alfonso VIII King of Castile |

Joan | William II King of Sicily |

John King of England r. 1199–1216 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Louis VIII King of France |

Otto IV Holy Roman Emperor |

Arthur I Duke of Brittany and Eleanor Fair Maid of Brittany |

Blanche of Castile Queen of France |

Henry III King of England r. 1216–1272 |

Richard of Cornwall King of the Romans |

Joan Queen of Scotland |

Alexander II King of Scotland |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

In Spanish: Enrique II de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Enrique II de Inglaterra para niños