Bronislava Nijinska facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bronislawa Nijinska

|

|

|---|---|

| Бронисла́ва Фоми́нична Нижи́нская | |

|

|

| Born |

Bronisława Niżyńska

January 8, 1891 |

| Died | February 21, 1972 (aged 81) Pacific Palisades, California, U.S.

|

| Occupation | Ballet dancer, choreographer, ballet teacher |

| Spouse(s) | Alexandre Kochetovsky Nicholas Singaevsky |

| Children | Leo Kochetovsky, Irina Nijinska |

| Relatives | Vaslav Nijinsky (brother) Kyra Nijinsky (niece) |

| Awards | National Museum of Dance's Mr. & Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney Hall of Fame, 1994 |

Bronislava Nijinska (born January 8, 1891 – died February 21, 1972) was a famous ballet dancer and a super creative choreographer from Russia. She was of Polish background. Bronislava grew up in a family of dancers who traveled a lot.

Her own dance career started in Saint Petersburg. Soon, she joined the Ballets Russes, a ballet company that became very successful in Paris. She faced tough times during wars and revolutions in Russia. But in France, people quickly loved her work, especially in the 1920s. After that, she continued to succeed in Europe and the Americas. Nijinska helped change ballet from old styles to more modern ones. She brought in new moves and simpler stories, paving the way for future ballet.

After serious training at home, she joined the state ballet school in Russia when she was nine. In 1908, she graduated as a top artist for the Imperial Theatres. A big moment came in Paris in 1910 when she joined Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. For her solo dance, Nijinska created the role of Papillon in Carnaval.

She helped her famous brother Vaslav Nijinsky create his new and sometimes surprising dances. These included L'Après-midi d'un faune (1912) and The Rite of Spring (1913).

She developed her own art in Russia during the Great War and the Russian Revolution. While performing, she also started designing her own dances. Nijinska opened a ballet school in Kiev with new ideas. She also wrote about the art of movement. In 1921, she left Russia because of the authorities.

When she rejoined the Ballets Russes, Diaghilev made her the main choreographer for the famous ballet company in France. Nijinska did great, creating several popular and modern ballets with new music. In 1923, she choreographed her famous ballet Les noces (The Wedding) with music by Igor Stravinsky.

From 1925 onwards, she designed and staged ballets for many different companies and places in Europe and the Americas. These included Teatro Colón, Ida Rubinstein, Opéra Russe à Paris, and her own companies.

Because of the war in 1939, she moved from Paris to Los Angeles. Nijinska kept working as a choreographer and artistic director. She also taught at her own studio. In the 1960s, she brought back her old ballets from the Ballets Russes days for The Royal Ballet in London. Her book, Early Memoirs, was published after she passed away.

Contents

- Early Life

- Her Career as a Dancer

- As a Choreographer

- In 'the Russias' During War and Revolution

- Diaghilev's 'Ballets Russes' in Paris and Monte Carlo 1921–1925

- Her Initial Choreographic Work

- Her Own Ballet Creations

- Le Renard (The Fox) (1922)

- Mavra (1922)

- Les noces (The Wedding) (1923)

- Les Tentations de la Bergère (Temptations of the shepherdess) (1924)

- Les Biches (The Does or 'the girls') (1924), also called The House Party

- Les Fâcheux (The Mad, or The Bores) (1924)

- La Nuit sur le Mont chauve (Night on Bald Mountain) (1924)

- Le Train Bleu (The Blue Train) (1924)

- 'Théâtre Chorégraphiques Nijinska', England & Paris 1925

- Companies and Exemplary Ballets 1926–1930

- 'Théâtre de l'Opéra' in Paris: Bien Aimée (or Beloved)

- Diaghilev's 'Ballets Russes' in Monte Carlo: Romeo and Juliet

- 'Teatro Colón' in Buenos Aires: Estudio Religioso, Choreographies for Opera

- 'Ida Rubinstein Ballet' in Paris: Boléro, La Valse, Le Baiser de la Fée

- 'Opéra Russe à Paris': Capriccio Espagnol [Rimsky-Korsakov]

- Her Dance Companies 1931–1932, 1932–1934

- Companies and Ballets 1935–1938

- Max Reinhardt's Hollywood Film: A Midsummer Night's Dream

- de Basil's 'Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo': Les Cent Baisers

- Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires: Le Baiser de la Fée, Opera Choreographies

- 'Markova-Dolin Ballet' in London, & Jamaica

- 'Ballet Polonais' in Warsaw: Concerto de Chopin, La Légende de Cracovie

- Ballet Companies and Exemplary Ballets 1939–1950s

- Ballet Companies: Revivals of Her Early Choreographies 1960–1971

- Based in Los Angeles, from 1940

- As Described by Others

- Personal and Family Life

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life

Bronislava Nijinska was the third child of Polish dancers Tomasz and Eleonora Nijinsky. Her parents were traveling performers in Russia. Bronislava was born in Minsk, but all three kids were baptized in Warsaw. She was the younger sister of Vaslav Nijinsky, a world-famous ballet star.

A Family of Dancers

Both of her parents started dancing in Warsaw at the Grand Theater. They later met as professional dancers with the Setov troupe in Kiev. They performed in cities across the Russian Empire. Her father, Tomasz Nijinsky, became a top dancer and ballet master. Her mother, Eleonora Bareda, was a main dancer.

Tomasz Nijinsky formed and led his own small dance group. He created silent plays and performed in circus-theaters. In 1896, he staged The Fountain of Bakhchisarai. Her mother Eleonora danced the princess, and Bronislava and her brother Vaslav watched. Tomasz also choreographed other successful ballets. Their family life was full of artists. Two African-American tap dancers, Jackson and Johnson, even visited their home and gave Nijinska her first lessons.

and Bronislava Nijinska,

sculpture by Giennadij Jerszow,

the Grand Theatre, Warsaw

Her father later left the family and traveled alone as a dancer. This led to a permanent separation from his wife. He saw his children less often.

Eleonora then settled the family in Saint Petersburg. She rented a large apartment and opened a guesthouse. Bronislava wrote that her brother Vaslav became upset with their father because of their mother's struggles.

Her Brother Vaslav

"By nature Vaslav was a very lively and adventurous boy." In her book Early Memoirs, Nijinska wrote about young Vaslav's adventures. Living with parents who danced and toured, the children became brave and physically strong. Their parents encouraged their athletic side. Vaslav loved exploring new places and testing his physical limits. This helped him become an amazing dancer. He quickly became famous at the Mariinsky Theater and then with Ballets Russes.

She described how Vaslav changed the Blue Bird role in The Sleeping Princess in 1907. He changed the costume and made the movements more energetic. When Nijinsky created L'Après-midi d'un Faune in 1912, he used Nijinska to practice it in secret. She followed his steps one by one. She also helped him create The Rite of Spring. However, she had to stop dancing the role of the Chosen Maiden because she was pregnant.

When her brother suddenly got married, Diaghilev ended his job at Ballets Russes. Bronislava Nijinska left the company to support him.

Vaslav Nijinsky married Romola de Pulszky during a 1913 tour in South America. This caused problems in the company. Nijinska explained that Vaslav was very private and didn't have many close friends in the dance world. He was alone on the tour when he married because her pregnancy kept her in Europe.

Nijinska thought that business reasons might have been behind Diaghilev's decision. By letting Nijinsky go, Diaghilev could get money and bring back the choreographer Fokine. This break was emotionally painful for her.

Her Childhood Dance Skills

Her parents not only danced on stage but also taught dance classes for adults and children. Early on, they taught Bronislava folk dances from different countries. She learned ballet and various dance steps. She even learned some acrobatic moves from her father. This rich experience helped her later in her own choreographies.

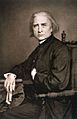

Bronislava was almost four when she first performed in a Christmas show with her brothers. She was always comfortable on stage. Her aunt Stepha, her mother's older sister, also helped her. Other dancers gave her lessons and tips. After her parents separated, her brother Vaslav Nijinsky joined the Imperial Theatrical School. When Bronislava was about nine, she started ballet lessons with the famous Enrico Cecchetti. He quickly saw her talent.

Imperial Theatrical School

In 1900, Bronislava was accepted into the state-supported school for performing arts. Her brother Vaslav had joined two years earlier. The school in Saint Petersburg had a long program. Her mother got help from people in the ballet world, like Stanislav Gillert and Cecchetti, for her to get in. At the entrance exam, 214 candidates showed their dance skills. Famous ballet master Marius Petipa and Cecchetti were there. Only twelve girls were accepted.

Bronislava graduated in 1908 with the 'First Award' for both dance and school subjects. Seven women graduated that year. She also became an 'Artist of the Imperial Theatre'. This gave her financial security and a special life as a professional dancer.

Her Career as a Dancer

Imperial Ballet in Saint Petersburg: 1908–1911

In 1908, Nijinska joined the Imperial Ballet (also known as the Mariinsky Ballet). She followed her brother's path. In her first year, she danced in the group in Michel Fokine's Les Sylphides. She learned a lot from Fokine's modern ideas. Both she and her brother Nijinsky left Russia in the summers of 1909 and 1910 to dance for Diaghilev's company in Paris.

Nijinska danced with the Mariinsky Ballet for three years. But the Ballets Russes in Paris was changing the ballet world. She felt she had to leave the Mariinsky after her brother Vaslav was dismissed. This meant she lost her special title and income as an 'Artist of the Imperial Theaters'.

Diaghilev & Ballets Russes in Paris: 1909–1913

Nijinska performed in Sergei Diaghilev's first two Paris seasons in 1909 and 1910. After leaving the Mariinsky, she became a full member of his new company, Ballets Russes. In 1912, she married fellow dancer Aleksander Kochetowsky. Their daughter Irina was born in 1913.

At first, Nijinska danced in the group, for example, in Swan Lake and Les Sylphides. As she improved, she got bigger roles. Her brother helped her prepare for the role of Papillon (the butterfly) in Michel Fokine's Carnaval (1909). She also changed the role of the Ballerina Doll in Petruchka (1912). She made the doll more realistic by wearing street clothes instead of a traditional tutu. She also stayed in character, which was new for classical ballet.

In the 1912 show Cléopâtre, she first danced the Bacchanale. Then she took over Tamara Karsavina's role of Ta-Hor. "Karsavina danced the role on toe, but I would dance it in my bare feet." She received many compliments for her dancing and acting in this role. The next year, she performed in her brother's Jeux (Games). Nijinska helped her brother Vaslav create The Rite of Spring, which premiered in 1913. She carefully followed his instructions for the Chosen Maiden role. But when she found out she was pregnant, she told him she couldn't perform, which made her brother angry.

In 1914, she danced for Saison Nijinsky (see section below).

In Petrograd with Sasha & in Kiev: 1915–1921

After Saison Nijinsky, Bronislava returned to Russia. She continued her ballet career as a dancer, with her husband Sasha as the male dancer. During the war and revolution, she performed in new and classic ballets. In Petrograd in 1915, she was listed as "the prima ballerina-artist of the State Ballet Bronislava Nijinska". She performed her own choreographed solos, Le Poupee and Autumn Song.

In Kiev, besides dancing, she started her ballet school and began choreographing. She danced solos in tunics, like Etudes and Nocturnes. In 1921, she left Russia and never returned.

Diaghilev's Ballets Russes: 1921–1925, and 1926

When she rejoined Ballets Russes in Paris, Nijinska first worked on Diaghilev's 1921 London revival of Marius Petipa's classic The Sleeping Princess. Even though it lost money, it was popular and well-designed. Nijinska danced the roles of the Hummingbird Fairy and Pierette, earning "high critical praise".

In 1922, Diaghilev asked her to perform the main role in Vaslav Nijinsky's L'Après-midi d'un Faune during its Paris revival. She had helped her brother with its choreography in 1912. "Vaslav is creating his Faune by using me as his model. I am like a piece of clay that he is molding..." But these performances were less important than her new job as the main choreographer.

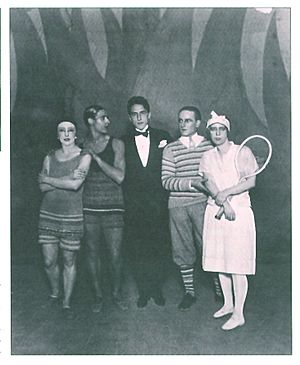

From 1921 to 1924, and in 1926, Nijinska also took important roles in many of her own ballets for Ballets Russes. She performed as the Lilac Fairy in The Sleeping Beauty (1921), the Fox in Le Renard (1922), the Hostess in Les Biches (1924), Lysandre in Les Fâcheux (1924), and the Tennis Player in Le Train Bleu (1924).

In Europe & the Americas: 1925–1934

Later, for her own ballet companies and others, she danced in roles she created. These included Holy Etudes, Touring, Le Guignol, and Night on Bald Mountain (all 1925). She also danced for Teatro Colón in Estudios religiosos (1926), in her Capricio Espagnole (1931), and the title role in Hamlet (1934). She performed into the 1930s in Europe and the Americas.

As Nijinska reached her forties, her performing career ended. An injury to her Achilles tendon in 1933 in Buenos Aires caused her to stop dancing.

Appraisals, Critiques

Her skills as a dancer are different from her more famous choreography. Lynn Garafola, a ballet critic, collected comments from her colleagues:

"She was a very strong dancer, and danced very athletically for a lady, and had a big jump," said Frederic Franklin. Anatole Vilzak remembered, "She had incredible endurance, and seemed never to be tired." English dancer Lydia Sokolova noted her "iron muscles in her arms and legs, and her highly developed calf muscles resembled Vaslav's." Alicia Markova, a top British ballerina, said Nijinska "was a strange combination, this terrific strength, and yet there was a softness."

The composer Igor Stravinsky said that "Bronislava Nijinska, sister of the famous dancer [is] herself an excellent dancer endowed with a profoundly artistic nature." After helping her brother Vaslav for months with The Rite of Spring, she found she was pregnant. She couldn't perform the main role. Vaslav then yelled at her, "There is no one to replace you. You are the only one who can perform this dance, only you, Bronia, and no one else!"

Nancy Van Norman Baer wrote that "Between 1911 and 1913, while [her brother] Vaslav Nijinsky's fame continued to soar, Nijinska emerged as a strong and talented dancer." Critic Robert Greskovic said that while she wasn't as beautiful as other famous dancers, "Bronislava Nijinska... began to make her mark as a choreographer."

Still, Nijinska must have been an excellent dancer. Even as a young student, top professionals recognized her talent. "If Marius Petipa patted her approvingly on the head and Enrico Cecchetti placed her, at age eight, front and center in his class... she must have been good." But before 1914, her brother's legendary dancing often overshadowed her own.

Her early style was known for its tough "virility." "Her own roles were packed with jumps and beats." Later, she combined her strength with an "unexpectedly poignant" emotional touch. She loved the flow of movement on stage.

As a Choreographer

"In her lifetime Nijinska choreographed over seventy ballets, as well as dance scenes for many films, operas, and other stage shows." She first helped her brother Vaslav Nijinsky with his choreographies for Ballets Russes. She would try out his new steps and ideas.

In 'the Russias' During War and Revolution

When World War I started, Nijinska, her husband, daughter, and mother were in Eastern Europe. Her brother Vaslav was in Austria. 'The Russias' here includes Ukraine and its capital, Kiev.

Russian art in the early 1900s was often new and experimental. After the 1917 revolution, Russia was chaotic. Many artists worked somewhat freely from Soviet politicians.

Petrograd, Her First Choreographies 1914–1915

When World War I began, Nijinska, her husband Aleksandr Kochtovsky ('Sasha'), and their baby daughter Nina returned to Petrograd. Nijinska had always thought of it as home. She taught ballet to Enrico Cecchetti's students. Newspapers reported that Bronislava and Aleksandr danced with former Ballets Russes colleagues like Michel Fokine and Tamara Karsavina.

Both became leading dancers at the Petrograd Private Opera Theatre. In 1915, Nijinska created her first choreographies: Le Poupée (The Doll) and Autumn Song. These were for her solo performances.

She was twenty-five. The 1915 program called her "the celebrated prima ballerina-artist of the State Ballet". Her Autumn Song used music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and The Doll by Anatoly Liadov. Fokine's ballets were also on that program. Her choreography for Autumn Song was "the more important" of her two solos and "owed a debt to Fokine".

Kiev 1915–1921, Her 'Ecole de Mouvement'

In August 1915, the family moved to Kiev. Nijinska's husband Sasha became ballet master at the State Opera Theater. They both worked on ballet scenes for operas and staged dance shows. In 1917, Nijinska started teaching at several places. In 1919, after their son Leon was born and her School of Movement opened, Sasha left the family and went to Odessa.

Treatise on Choreography

Nijinska's ideas about modern ballet began to take shape. In Moscow after the 1917 October Revolution, she started her book: The School of Movement (Theory of Choreography). It was published in 1920 but is now lost. Only a 100-page manuscript remains.

In a short essay from 1930, she summarized her main ideas: "On movement and the school of movement". Nijinska wrote:

Just as 1. Sound is the material of music; and 2. Colour is the material of painting; so 3. Movement constitutes the material of dance. ... The action of movement should be continuous, otherwise its life is interrupted. ... In choreography, transition should be movement. ... [T]he position of the body [a] result created by movement. ... [C]horeographic movement must have its own organic being (different in each composition), its own breathe and rhythm. ...

[The artist] sings the movement of his dance [so that] the spectator ... hears with his eyes the melody of [its] movement ... The artist [of dance] must perfectly see and know movement in its entire nature, must work the movement as the material of his art. ... [C]lassical dance teaches only separate pas--movements. The secret of thinking and acting between positions [is] Movement ...

N. V. N. Baer noted that Nijinska's theory of dance, 'the school of movement', aimed to add new ways of moving to classical ballet. "It is in this essay that she documents her search for a new means of expression based on the extension of the classical vocabulary of dance steps."

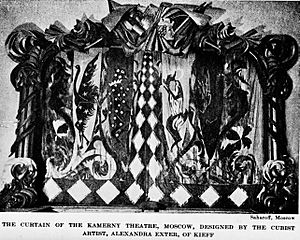

Collaboration with Designer Exter

In 1917, Nijinska met the artist Alexandra Exter in Moskva. Exter's designs used constructivist ideas. They shared their views on modern art and theater. This began a long and successful partnership, with Exter designing sets and costumes. Their work together continued into the 1920s, even after they both moved to Paris.

Before the war, Exter lived in Western Europe and joined "cubist and futurist circles." Returning to Russia, Exter settled in Moscow. She aimed to create "synthetic theater" with Alexander Tairov. In 1918, Exter moved to Kiev and opened an art studio, which was also a meeting place for artists.

Art discussions were held at Nijinska's dance school, where Exter joined in. Their ideas matched well. Curator Nancy Van Norman Baer wrote that they became "close artistic associates" and "fast friends".

Les Kurbas also worked with Nijinska. He was a Ukrainian theater producer and film director. They had a "complementary and deep" collaboration, sharing studio space and discussions.

Her Ballet School and its Productions

In February 1919 in Kiev, she opened her dance school called L'Ecole de Mouvement (School of Movement). This was shortly after her son Léon was born. Her school's goal was to prepare dancers to work with new choreographers. She taught her students about flowing movement, free use of the torso, and quick linking of steps. She wanted them ready for modern ballets, like those she helped her brother design.

At this school, she staged concerts with her own solo dances. These included "her first plotless ballet compositions": Mephisto Valse (1919), Twelfth Rhapsody (1920) by Liszt, and Nocturne (1919) and Marche Funèbre (1920) by Chopin. These solo dances might be "the first abstract ballets" of the 20th century.

Many of her students danced for the public, and Serge Lifar was the most outstanding. She began to be recognized as a choreographer. The Ministry of Arts then invited Nijinska to stage a full production of Tchaikovsky's ballet Swan Lake. She changed the classic Petipa and Ivanov choreography from 1895. She made it easier for her less experienced students. The show was at Kiev's State Opera Theater.

Reasons for Leaving Kiev

It was thought that Nijinska left Kiev in 1921 to visit her brother Vaslav Nijinsky in Vienna because of his health. But she learned about her brother in 1920, when the Russian civil war prevented travel.

Recent research by Prof. Garafola shows a different reason. The Cheka, the Soviet security police, started harassing her and her students in early 1921. Her artistic freedom was challenged, and by April, L'Ecole de Mouvement was closed.

She left Kiev secretly, helped by other dancers. She took her two children, Irina (seven) and Leon (two), and her mother (sixty-four). After bribing border guards, they crossed the Bug River into Poland in May 1921.

Weeks later in Vienna, they visited her brother Vaslav, his wife Romola, and their children Kyra and Tamara. His health had worsened since 1914. He had not performed since 1917. Despite the sadness, the family was reunited. Bronislava earned money by working at a cabaret in Vienna. Then Diaghilev invited her to Paris, paying for her train ticket. She left her children with her mother and went to rejoin Ballets Russes.

Diaghilev's 'Ballets Russes' in Paris and Monte Carlo 1921–1925

The company staged ballets for twenty years, from its opening in 1909 to its founder Sergei Diaghilev's death in 1929. He managed everything: business, music, choreography, dance, and costumes. He worked mainly with five choreographers: Fokine, Nijinsky, Massine, Nijinska, and Balanchine. The early 1920s were Nijinska's time as the main choreographer.

The company started in Russia to "export Imperial culture" but never performed in Russia. By 1918, less than half its dancers were Russian. The company's link to Russia weakened after the wars and revolutions. In 1922, it moved its base from Paris to Monte Carlo for financial reasons.

Her Initial Choreographic Work

In 1921, Diaghilev asked Nijinska to return to Ballets Russes mainly for her choreography. He knew about her recent work in Kiev, especially how she staged Petipa-Ivanov's classic Swan Lake. He hired her "because" of her abilities. She was to be ballet mistress, a principal dancer, and the company's first and only female choreographer. Diaghilev was careful. To test her work, and because of the company's money problems, he first gave Nijinska big tasks in his current ballet shows.

The Sleeping Princess, originally La Belle au bois dormant (1921)

In late 1921, Ballets Russes faced a big money crisis. This was because of its expensive London production of The Sleeping Beauty. The 1921 version was renamed The Sleeping Princess.

The ballet was "one of the great Petipa classics from the old Imperial Russian repertory". La Belle au bois dormant (The beauty in woods asleep) came from a French fairy tale by Charles Perrault. Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed the music. Diaghilev brought back the entire three-act ballet. Léon Bakst designed the very grand sets.

Nijinska was recognized for "Additional choreography". Her most famous part was adding the lively hopak for the 'Three Ivans' in Act III. It "became one of the most popular numbers". Nijinska designed several other pieces and led rehearsals. As a principal dancer, she played the Hummingbird Fairy, the Lilac Fairy, and Pierrette. She choreographed a new "finger" variation for herself as the Hummingbird Fairy.

In 1921 London, Nijinska showed her mastery of dance, staging, and design. The Sleeping Princess production "became a proving ground of Nijinska's choreographic talent. She acquitted herself admirably."

Diaghilev's decision to revive the 1890 Russian classic was risky. He wanted excellence, no matter the cost. Many critics were disappointed by the traditional approach, as Ballets Russes was known for experiments. However, Diaghilev's classic was very popular with London's growing ballet audience. But in late 1921, there weren't enough ticket sales to cover the huge costs. The brilliant production became a huge financial disaster.

Nijinska arrived at Ballets Russes in mid-1921, coming from the creative chaos of 'Russia in revolution'. Her artistic taste favored the experimental Ballets Russes of before the war. Yet The Sleeping Princess was her first job. She later wrote that Diaghilev's grand revival "seemed to me an absurdity, a dropping into the past". Nijinska felt the stress of this artistic difference: "I started my first work full of protest against myself."

Throughout her career, Nijinska didn't stay a radical experimenter, nor did she fully accept old ballet traditions. She liked new ideas about movement but chose a middle path: mixing traditional art with new ideas.

Aurora's Wedding, or Le Mariage de la Belle au bois dormant (1922)

After months, money problems forced the closure of The Sleeping Princess. To get some money back, Diaghilev asked Stravinsky and Nijinsky to create a shorter version. They reworked the dance and music into "a one-act ballet, which he called Aurora's Wedding." It became very popular and a commercial success, staying in Ballets Russes' shows for decades.

Aurora's Wedding premiered in Paris in May 1922. Since the London costumes were taken by creditors, they used old ones and new ones by Gontcharova. The main dancers were Vera Trefilova and Pierre Vladimirov. Nijinska shared the choreography credit with Petipa.

La Fête Merveilleuse (The Marvelous Festival) (1923)

This show was mostly taken from Aurora's Wedding. La Fête was performed by Ballets Russes in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles. It appealed to the French love for old 18th-century shows. Rich audiences from all over Europe and America came. Nijinska staged it, Stravinsky re-arranged Tchaikovsky's music, and Juan Gris designed the costumes.

Les Contes de Fées (Stories of the fairies) (1925)

Les Contes de Fées was another spin-off from The Sleeping Princess, taken from fairy tales in Aurora's Wedding. It premiered in Monte Carlo in February 1925. Diaghilev produced it and other ballets without scenery that winter.

Her Own Ballet Creations

Nijinska was the sole choreographer for nine works at Ballets Russes in the 1920s. All but one used modern music: three by Igor Stravinsky (two ballets, Renard, Noces, and an opera, Mavra); three by French composers; one by an English composer; and one by Modest Mussorgsky. One work used baroque music.

Le Renard (The Fox) (1922)

Nijinska's first ballet as choreographer for Ballets Russes was Le Renard, a "burlesque ballet with song". Igor Stravinsky composed the music and wrote the lyrics. It was first performed in 1922.

The main dancers were Nijinska (as the Fox), Stanislas Idzikowski (as the Cock), Jean Jazvinsky and Micel Federov (as the Cat and the Goat). Costumes and sets by Michel Larionov were in a modern, "primitive" style.

The story comes from old Russian folk tales about a trickster fox. The Fox tries to trick the Cock to eat him, but the Cock is saved by the Cat and Goat. The Fox disguises himself as a nun and a beggar.

Nijinska's choreography was modern. She mixed animal-like grace with strange and funny poses. Singers off stage told the story. Larionov's designs included simple animal masks and character names written on the costumes.

Nijinska discussed Fokine's "Dance of the Fauns" (1905), where fauns looked like animals. The young boys dancing them "tumbled head over heels," which wasn't classical ballet. But Fokine said it fit the "animal characteristics."

Even though Le Renard was not well-received, Diaghilev and Stravinsky were happy with Nijinska's work. Diaghilev hired her as the permanent choreographer.

The premiere of this ballet also inspired a special dinner party. It was a "modernist summit" with famous artists like Proust, Joyce, Stravinsky, and Picasso. This shows how close ballet was to the avant-garde (new and experimental art) in those years.

Mavra (1922)

This was an "opéra bouffe" with music by Stravinsky, first performed in Paris in June 1922. The story by Boris Kochno was based on a poem by Alexander Pushkin. The one-act opera didn't need dances, but Diaghilev asked Nijinska to stage the movements of the four singers.

Les noces (The Wedding) (1923)

Nijinska created the ballet Les noces (The Wedding) from music and story by Igor Stravinsky. The 24-minute ballet shows events around a peasant wedding in an abstract way. Dancers found the intense group movements difficult at first. "When you are truly moving together your individuality is really evident." It moved away from light folk dance. Nijinska showed a serious view of folk society, but also a lively vision. The heavy, collective mood was balanced by hints of peasant wit and survival.

Stravinsky's music for Les noces uses sharp rhythms and voices. It doesn't show the wedding as a joyful ritual. The ballet has a darker, more anxious mood, showing a "deeply moving evocation" of the ceremony. Nijinska translated this into dance, showing the fate of tradition and revolution. The lyrics came from Russian folk songs.

Stravinsky said his text for Les noces was like "overhearing scraps of conversation without the connecting thread of discourse." The singers' voices seem separate from their characters. Stravinsky's music is fluid and layered, but sometimes jarring. It uses percussion and four pianos.

Dance writer Robert Johnson said Stravinsky's text showed his interest in psychology and a collective unconscious. The contrast in the music represents a dialogue between everyday time and sacred time. However, Stravinsky described the ballet as a "masquerade" or "divertissement," meant to be funny. Nijinska disagreed, and her serious vision of the ballet won.

The simple costumes and sets were by Natalia Goncharova. She first suggested bright, colorful designs, but Nijinska thought they were wrong. Goncharova then changed her designs to look like rehearsal clothes. George Balanchine's practical dance clothes for performances "can trace precedents back to Noces." Goncharova's simple sets and costumes are now "inseparable from the ballet's musical and movement elements."

Nijinska researched Russian peasant customs. But she mostly followed Stravinsky's modern music. She made the women dance en pointe (on their toes) to make them look taller and like Russian icons. The sound of their pointes hitting the floor showed strength. The women often moved together. The group often faced the audience directly, which was different from classical ballet. Towards the end, the women handled very long, thick braids of the bride's hair, like "sailors taking up the mooring lines of a boat." The whole piece, linked to old folk traditions, had a strong sense of controlled conformity.

Her choreography showed Nijinska's interest in modern abstract art. Forms like the "cart" taking the Bride from home and the "cathedral" grouping at the end were abstract. Gestures like braiding hair and sobbing were also abstract. Pyramidal and triangular shapes represented "spiritual striving," possibly influenced by painter Wassily Kandinsky.

A famous pose from Les noces shows the heads of the bridesmaids stacked up.

Dance critic Janice Berman wrote that Nijinska saw the wedding from a woman's view: "Nijinska was obviously a feminist; the solemnity of the nuptials derives not only from the sanctity of married love, but from its downside---a loss of freedom, particularly for the bride." The critic Johnson also noted that Les noces is full of images of dreamers.

"Les noces was Nijinska's answer to The Rite," continuing her brother's work. It was "a reenactment of a Russian peasant wedding." The ballet showed the ceremony as "not a joyous occasion but a foreboding social ritual." Critic André Levinson called her choreography "Marxist" because the individual was lost in the crowd. But Nijinska escaped her brother's dark ideas by following Stravinsky's lead through the beauty of the Orthodox liturgy. Still, the ballet was "a modern tragedy... that celebrated authority" but also showed its "brutal effect on the lives of individuals."

Lynn Garafola noted that Ballets suédois (Swedish ballet) was a big competitor to Diaghilev's Ballets Russes in the early 1920s. But Garafola admired Nijinska's 1922 ballet Le Renard.

"Bronislava Nijinska's Les noces [grew] out of boldness of conception without regard for precedent or consequences," wrote John Martin, dance critic for The New York Times. Nijinska herself wrote about Noces: "I was informed as a choreographer [by my brother's ballets] Jeux and The Rite of Spring. The unconscious art of those ballets inspired my initial work."

Les Tentations de la Bergère (Temptations of the shepherdess) (1924)

This one-act ballet used baroque music by Michel de Montéclair, arranged by Henri Casadesus. The sets, costumes, and curtain were by Juan Gris. It was also called L'Amour Vainqueur (Love Victorious). It opened in Monte Carlo.

In the mid-1920s, Ballets Russes started moving away from modernism. This included Les Tentations de la Bergère and Les Fâcheux, also by Nijinska. These two works focused on 18th-century France, reflecting France's post-war interest in old monarchies.

Les Biches (The Does or 'the girls') (1924), also called The House Party

Les Biches (The Girls) is a one-act ballet about a house party for single people. It has music by Francis Poulenc. The sets and costumes were by cubist painter Marie Laurencin. Poulenc's music was "mischievous, mysterious, now sentimental, now jazzy."

Dance writer Robert Johnson said that beneath the sunny setting of this ballet were "shadowy scenes painted by Watteau." Poulenc described a section as "a kind of hunting game, very Louis Quatorze."

It opened in January 1924 in Monte Carlo. "La Nijinska herself" was in the cast, along with Ninette de Valois. The French title Les Biches means "the girls" or female deer, and was "1920s terminology for young women." Some English companies changed the title to The House Party or The Gazelles.

Diaghilev praised Nijinska to Poulenc, but feared she might not like the music. However, "Poulenc and Nijinska had taken to each other enormously." During rehearsals, Poulenc said, "Nijinska is really a genius" and her choreography's "pas de deux is so beautiful that all the dancers insist on watching it."

The ballet's story is not clear. Poulenc said it had an atmosphere of "wantonness." Richard Buckle asked, "Have the three athletes... just dropped in from the beach, or are they customers?...It is so delightful not to know." Les Biches was meant to be a modern "fête galante," and a comment on Fokine's Les Sylphides.

Nijinska played the hostess of the house party. She was "a lady no longer young, but very wealthy and elegant."

Dance writer Richard Shead called Les Biches "a perfect synthesis of music, dance, and design."

After World War I, Diaghilev wanted a French-themed, neo-classical work. But Nijinska's dance in Les Biches was not entirely traditional. It mixed difficult classical steps with athletic poses and popular dance moves. In this way, Les Biches is "the fountainhead of neoclassicism in dance." According to Irina Nijinska, the choreographer's daughter, some gestures in the ballet are military salutes that Nijinska made abstract, like Cubism.

Garafola said Diaghilev disliked the ballet's sad view of gender relations. It showed femininity as "only skin-deep, a subterfuge applied like make-up." The usual "male bravura dance" was shown as fake. The ballet "divorces the appearance of love from its reality." Garafola suggested Les Biches might show Nijinska's "unease with traditional representations of femininity."

George Balanchine, Nijinska's successor, praised Les Biches as a "popular ballet of the Diaghilev era". It was brought back many times and was very popular. "Monte Carlo and Paris audiences... loved it."

Les Fâcheux (The Mad, or The Bores) (1924)

Les Fâcheux was originally a three-act comedy ballet by French playwright Molière (1622–1673). It opened in 1661. In the Ballets Russes version, the music was by Georges Auric, sets by Georges Braque, and choreography by Nijinska.

Nijinska danced the male role of Lysandre, wearing a wig and 17th-century clothes. Anton Dolin as L'Elégant danced on point, which was a sensation. "Her choreography incorporates mannerisms and poses from the period that she modernized by stylization." Braque's costumes were 'Louis XIV'. The original music was lost, so Auric created new music that sounded old but was modern.

Georges Auric was part of a group called Les Six with other French composers. Jean Cocteau liked this group's new approach to arts. Ballets Russes also started using their music. Some critics called their music musiquette. But critic Lynn Garafola sees "gaiety and freshness" in these ballets. Garafola also likes "the independence of the music in relation to the choreography."

However, Ballets Russes dancer Lydia Lopokova felt that Nijinska's Les Fâcheux was smooth but didn't move her. She preferred old-fashioned ballets with simplicity and poetry. She felt that Massine and Nijinska's choreography had "too much intellect."

La Nuit sur le Mont chauve (Night on Bald Mountain) (1924)

The ballet premiered in April 1924 in Monte Carlo. Nijinska's choreography used music by Modest Mussorgsky. Some ballet designs experimented with costumes that changed the body's natural shape. For Night on Bald Mountain, Nijinska's sketches showed "elongated, arc-like forms." The costumes by Alexandra Exter "played with shape" and "played with gender".

Nijinska focused on the group rather than individual dancers. She used the main group of dancers as the central figure, which was unusual. This made the "movement of the dancers to blend... they became a sculpted entity." Exter also "depersonalized the dancers, clothing them in identical gray costumes." But it was "the architectural poses of Nijinska's choreography that gave the costumes their distinctive shape".

Mussorgsky's 1867 'symphonic poem' was inspired by a witches' sabbath story by Nikolai Gogol. The composer revised it and put it into his unfinished opera. The music was re-arranged by Rimsky-Korsakov.

Le Train Bleu (The Blue Train) (1924)

The ballet Le train blue was called a 'danced operetta'. Darius Milhaud composed the music, and Jean Cocteau wrote the story. The dancers' costumes were designed by 'Coco' Chanel, including "bathing costumes of the period". The scenery was by sculptor Henri Laurens. The cast included a handsome kid (Anton Dolin), a bathing belle (Lydia Sokolova), a golfer (Leon Woizikowski), and a tennis player (Nijinska).

Cocteau's story was simple. The title refers to the actual Train Bleu, which went to the Côte d'Azur, a fashionable resort. Diaghilev joked, "The first point about Le train bleu is that there is no Blue Train in it." The story "took place on a beach, where pleasure-seekers disported themselves." Inspired by young people "showing off" with "acrobatic stunts," the ballet was "a smart piece about a fashionable plage" (beach).

People's love for sports made Cocteau think of a 'beach ballet'. It also gave a great role to the athletic Anton Dolin, whose "acrobatics astonished and delighted the audience." When he left the company, no one could replace him, so the ballet was stopped.

The ballet likely suffered when Nijinska and Cocteau's collaboration broke down. Garafola wrote that they disagreed on: (a) gender roles; (b) Cocteau's story and gesture approach versus 'abstract ballet'; and (c) the changing look of dance. Last-minute changes were made. Nijinska's choreography presented a sophisticated view of the beach ballet. Garafola suggested that "Only Nijinska had the technical wherewithal... to wrest irony from the language and traditions of [classical dance]."

Le train bleu was similar to the 1933 ballet Beach. Massine's choreography, like Nijinska's, used stylized sport moves and different dance styles within ballet. Both included jazz movements. Fifty years later, Nijinska's 1924 choreography was brought back.

'Théâtre Chorégraphiques Nijinska', England & Paris 1925

Leaving Diaghilev, Start of Her Dance Company

Nijinska left Ballets Russes in January 1925. She left partly because of her sadness when Diaghilev sided with Cocteau over Le Train Bleu. She wanted to lead her own company. Another reason was the arrival of George Balanchine in 1924, who came with an experimental dance group from the Soviet Union. Diaghilev saw his talent and hired him for Ballets Russes. Balanchine took over Nijinska's choreographer position.

In 1925, Nijinska found enough money to start her ballet company: Théâtre Chorégraphiques Nijinska. It was a small group with eleven dancers. The Russian artist Alexandra Exter designed the costumes and sets. Nijinska had met Exter in Kiev during the war. Their professional relationship continued when Nijinska choreographed for Ballets Russes. Nancy Van Doren Baer highly praised their teamwork, calling it "a most dramatic synthesis of the visual and the kinetic".

For her company, Nijinska choreographed six short ballets and danced in five. She also staged four shorter dance pieces, dancing one solo. For the 1925 summer season, her ballet company toured fifteen English towns. Then it performed in Paris at an exhibition and a gala. "Judged by any standard, the Théâtre Chorégraphiques offered dancing, choreography, music, and costume design of the highest order."

Holy Etudes, an Abstract Ballet [Bach]

Her first abstract ballet seen outside Russia, set to J. S. Bach's First and Fifth Brandenberg Concertos, was also the first ballet made to his music. The dancers wore identical silk tunics and capes with halo-like headgear. "Exter's 'uni-sex' costumes were revolutionary." Their simple design "added immeasurably to the broad flowing movement and stately rhythms of the choreography, suggesting androgynous beings moving in heavenly harmony."

Silk "enhanced the ethereal quality of the ballet. The brilliant pink and bright orange capes hung straight from bamboo rods." Baer also noted, "By varying the levels, groupings, and facings of the dancers, Nijinska created a pictorial composition made up of moving and intersecting planes of color." As in Les noces, Nijinska used dancing en pointe "to elongate and stylize the line of the body".

Her short, abstract Bach ballet was one of the creations "she cared most about." She kept changing its choreography and presented it in different forms and titles.

Five Short Modern Pieces, Four Divertissements

- i. Touring (or The Sports and Touring Ballet Revue).

Nijinska "took contemporary forms of locomotion as her theme", with music by Francis Poulenc, costumes and set by Exter. "Cycling, flying, horse-riding, carriage driving... were all reduced to dancing." It showed how ballet could connect to modern life, following her brother Vaslav Nijinsky's Jeux and her Les Biches and Le Train Bleu of 1924.

- ii. Jazz.

The music was Igor Stravinsky's 1918 composition Ragtime. Stravinsky wrote it "was indicative of the passion I felt at that time for jazz... enchanting me by its truly popular appeal, its freshness, and the novel rhythm." Exter's costumes were inspired by an 1897 Russian show. Nijinska's choreography is lost. As children, she and her brother Vaslav had befriended two African-American tap dancers who stayed at their parents' home.

- iii. On the Road. A Japanese pantomime.

Based on a Kabuki story, with music by Leighton Lucas, and costumes by Exter. Nancy Van Norman Baer thought it came from a solo called Fear that Nijinsky designed and danced in Kiev in 1919, inspired by a Samurai warrior. Nijinska mentioned a Japanese influence on her early works, from prints she bought in 1911.

- iv. Le Guignol

The title character is from a French puppet show. Music by Joseph Lanner. It was later performed in 1926 in Buenos Aires.

- v. Night on Bald Mountain.

An shorter version of her 1924 work for Ballets Russes. "As in Holy Etudes and Les noces, Nijinska relied on the ensemble instead of using individual dancers to express the ballet-action."

- Four divertissements.

The Musical Snuff Box was a new version of the solo La Poupée first danced by Nijinska in Kiev. Trepak was her The Three Ivans that she choreographed for Diaghilev's The Sleeping Princess in London. The Mazurka to Chopin was from Les Sylphides. Polovetsian Dances was a group dance for the whole company.

Companies and Exemplary Ballets 1926–1930

During these years, Nijinska continued to choreograph, direct, and dance for various ballet companies, including Diaghilev's in 1926 and Teatro Colón in Argentina.

'Théâtre de l'Opéra' in Paris: Bien Aimée (or Beloved)

At the Paris Opera, Nijinska choreographed the ballet La Rencontres (The Encounters). In 1927, she presented another new ballet, Impressions de Music-Hall. She also choreographed dances for several operas.

Bien Aimée, a one-act ballet in 1928, was choreographed by Nijinska. It used music from Franz Schubert and Franz Liszt, and sets by Alexandre Benois. The dancers included Ida Rubinstein. Its simple story features a poet remembering his lost Muse and his youth. The ballet was brought back by the Markova-Dolan company in 1937. Ballet Theatre in New York City arranged for Nijinska to stage its American premiere in 1941/1942.

Diaghilev's 'Ballets Russes' in Monte Carlo: Romeo and Juliet

A new version of Romeo and Juliet with music by Constant Lambert premiered in 1926. Leonide Massine was impressed by it. "Nijinska's choreography was an admirable attempt to express the poignancy of Shakespeare's play in the most modern terms." At the end, the main dancers Tamara Karsavina and Serge Lifar, who were lovers in real life, "eloped in an aeroplane". Max Ernst did design work, Georges Balanchine an entr'acte. Massine later wrote, "It seemed to me that this ballet was far in advance of its time."

'Teatro Colón' in Buenos Aires: Estudio Religioso, Choreographies for Opera

In 1926, Nijinska became choreographic director and principal dancer with Teatro Colón (Columbus Theater). She worked with the Buenos Aires company until 1946. In 1926, she found "an inexperienced but enthusiastic group of dancers" there.

Nijinska staged Un Estudio Religioso to music by J. S. Bach in 1926, which she developed from her 1925 Holy Etudes. At Teatro Colón, she expanded the work for a full company. She used new ideas she first developed in Kiev. Both these Bach ballets had no story.

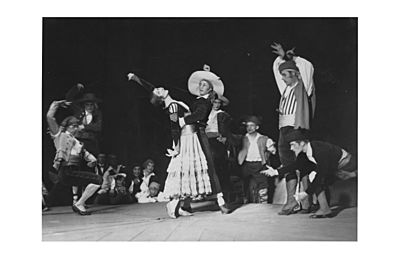

In 1926 and 1927, Nijinska created dance scenes for fifteen operas in Buenos Aires, including Bizet's Carmen and Wagner's Tannhäuser. In 1927, she directed Fokine's ballet choreography for Ballets Russes: Ravel's Daphnis et Chloë and Stravinsky's Petrouchka.

'Ida Rubinstein Ballet' in Paris: Boléro, La Valse, Le Baiser de la Fée

The dancer Ida Rubinstein started a ballet company in 1928, with Bronislava Nijinska as its choreographer. Rubinstein quickly asked Maurice Ravel to compose music. One of Ravel's pieces, his Boléro, became popular and famous right away.

For Rubinstein, Nijinska choreographed the original Boléro ballet. She created a scene around a large circular platform, with individual dancers. The ballet always returned to the center. The dramatic movements were inspired by Spanish dance but were simplified.

Rubinstein had danced for Diaghilev in the early years of Ballets Russes. In the 1910 ballet Scheherazade, she and Vaslav Nijinsky had main roles. They also danced together in Cléopâtre.

After Bolero, Rubinstein had her company prepare another ballet choreographed by Nijinska, with music by Ravel: his La valse. It opened in Monte Carlo in 1929. The ballet was often brought back, most famously by Balanchine in 1951.

A ballet called Le Baiser de la Fée (Kiss of the Fairy) started when Ida Rubinstein asked Igor Stravinsky to compose music for Bronislava Nijinska to choreograph. It would be staged in Paris in 1928. Stravinsky chose Hans Christian Andersen's tale of The Ice-Maiden as inspiration, but he changed the story. He saw the fairy as Tchaikovsky's Muse whose kiss inspired his music.

Stravinsky conducted the orchestra for the ballet's first performance in Paris in 1928. The dancers included Rubinstein. Le Baiser de la Fée played in other European cities and in Buenos Aires. In 1935, Frederick Ashton choreographed a new version, and in 1937, George Balanchine did one for New York.

'Opéra Russe à Paris': Capriccio Espagnol [Rimsky-Korsakov]

This ballet company was founded in 1925. A main figure was Wassily de Basil. After Sergei Diaghilev's death in 1929, there was a gap in European ballet.

Nijinska joined 'Opèra Russe à Paris' in 1930. She was "to choreograph the ballet sequences" in several famous operas. She also "to create works for the all-ballet evenings." She created the ballet for Capriccio Espagnol by Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. She also staged some of her previous ballets (Les noces and Les Biches) and other Ballets Russes shows.

In 1931, she turned down a good offer from de Basil to start her own company, 'Ballets Nijinska'. She wanted to work independently. Later in 1934 and 1935, she worked with de Basil's company again.

René Blum was "organizing the ballet seasons at the Casino de Monte Carlo." In 1931, he started talks with de Basil about combining ballet operations, leading to 'Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo'. De Basil would provide dancers, shows, sets, and costumes, and Blum the theater and money. A contract was signed in January 1932. Soon, Blum and de Basil disagreed and split in 1936. Later in the 1940s, Nijinska staged works for a successor to Blum's company.

Her Dance Companies 1931–1932, 1932–1934

In the early 1930s, Nijinska formed and led several of her own ballet companies. In 1934, a mistake led to her theater equipment being taken. This forced her to cancel her autumn shows. She then accepted an offer to choreograph for films and returned to working for other companies.

'Ballets Nijinska' in Paris: Etude-Bach, Choreographies for Opéra-Comique

In 1931, while still staging dance for 'Opera Russe à Paris', Nijinska started working independently under her own name: 'Ballets Nijinska'. She choreographed ballets for operas at the Opéra-Comique of Paris and the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées.

In 1931, her company staged Etude-Bach with new decor and costumes. This was a new version of her 1925 Holy Etudes and her 1926 Un Estudio Religioso.

'Théâtre de la Danse Nijinska' in Paris: Variations [Beethoven], Hamlet [Liszt]

From 1932 to 1934, Nijinska led her Paris-based company, 'Théâtre de la Danse Nijinska'. A new ballet Variations was staged in 1932, inspired by Beethoven. The dancers followed a difficult theme: the changing fate of nations. The costumes and decor were by Georges Annenkov.

In 1934, she designed a ballet Hamlet, based on Shakespeare's play, with music by Hungarian composer Franz Liszt. Nijinska played the main role. "Her choreography... emphasized the feelings of the tragedy's tormented characters." Nijinska created "three aspects for each of the protagonists": the real character, his soul, and his fate, played by different groups of dancers like "a Greek chorus." A similar Hamlet ballet was later staged in London.

Her company performed two of her famous ballets from the mid-1920s: Les Biches in 1932 and Les noces in 1933. Nijinska's Théâtre de la Danse had ballet seasons in Paris and Barcelona and toured France and Italy. The company's 1934 season featured several ballets.

In 1934, Nijinska joined her dance company with Wassily de Basil's company Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. For the 1934 Opera and Ballet seasons, she directed the combined companies' shows in Monte Carlo.

Later in 1934, 'Théâtre de la Danse Nijinska' lost its costumes and sets. They were mistakenly taken to pay artists from another company. Nijinska was not at fault, but she didn't get them back until 1937.

This forced her to cancel all her company's shows for the autumn tour. Her dancers then found other work. Nijinska was offered a choreography contract by a film producer, so she left Paris for Hollywood.

Companies and Ballets 1935–1938

Max Reinhardt's Hollywood Film: A Midsummer Night's Dream

In 1934, Max Reinhardt asked Nijinska to go to Los Angeles and choreograph the dance scenes for his 1935 film A Midsummer Night's Dream. It was a Hollywood version of the William Shakespeare comedy, with music by Felix Mendelssohn. Much of the music came from Mendelssohn's two compositions about this play. Los Angeles seemed to suit Nijinska, as she later made it her home.

A Midsummer Night's Dream had been choreographed as a one-act ballet in Saint Petersburg by Marius Petipa in 1876 and by Mikhail Fokine in 1902. A performance of Fokine's choreography in 1906 was special for Nijinska. She danced in it, and it was the first time her father visited after a long absence.

This 1935 film was not Nijinska's first time working for Max Reinhardt. In 1931, she had created ballet scenes for Offenbach's opera The Tales of Hoffmann for a Reinhardt production in Berlin.

de Basil's 'Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo': Les Cent Baisers

Nijinska choreographed Les Cent Baisers (The hundred kisses) in 1935 for de Basil's company. This one-act ballet used music by Frédéric Alfred d'Erlanger. It opened in London at Covent Garden.

The story by Boris Kochno followed the fairy tale "The swineherd and the princess" by Hans Christian Andersen. In it, a disguised prince tries to win over an arrogant princess. Nijinska's choreography is seen as one of her more classical works. But she added subtle changes to the usual steps, giving it a special Eastern feel, according to Irina Baronova, who danced the princess.

Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires: Le Baiser de la Fée, Opera Choreographies

Nijinska had presented her ballet Le Baiser de la Fée (Kiss of the fairy) at Teatro Colón in 1933. She first staged it for Ida Rubinstein's Company in 1928. It was based on Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale The Ice-Maiden. But Igor Stravinsky changed the eerie maiden into a helpful Muse.

In 1937, Nijinska returned to Buenos Aires for a repeat performance of Le Baiser de la Fée. She also created ballet choreography for dance scenes in operas at Teatro Colón, using music by composers like Mussorgsky, Verdi, and Wagner.

'Markova-Dolin Ballet' in London, & Jamaica

In 1937, Nijinska brought back her 1924 Les Biches for a performance by the Markova-Dolin troupe. "For six months during 1937, the troupe was creatively bolstered by the presence of Nijinska, who took charge of rehearsals and classes."

Alicia Markova was a leading ballerina in London. In 1935, she left the Vic-Wells ballet company to "form the Markova-Dolin Company (1935–1938), with Bronislava Nijinsky as chief choreographer." Irish dancer Anton Dolin had worked with Ballets Russes since 1921. He often danced with Markova in the 1930s.

After the war, Nijinska choreographed Fantasia for the Markova-Dolin company, with music by Schubert and Liszt. It opened in 1947 in Kingston, Jamaica.

In the 1930s, Nijinska gave Alicia Markova special ballet lessons, including for her own choreographies. She taught Markova an early work from Kiev: Autumn Song by Tchaikovsky. Nijinska had originally danced it barefoot in a tunic. In 1953, Markova performed this solo ballet on television.

'Ballet Polonais' in Warsaw: Concerto de Chopin, La Légende de Cracovie

In 1937, Nijinska was asked to be the artistic director and choreographer for the new Balet Polski (The Polish Ballet). Its goals were to promote Polish dance, train new dancers, and perform internationally. She signed a 3-year contract. For the company's 1937-1938 debut season, she created five new ballets.

For the Exposition Internationale in Paris, the five ballets opened in November 1937. They were well received. Ballet Polonais won the Grand Prix for performance, and Nijinska won the Grand Prix for choreography. The company then toured London, Berlin, and Warsaw.

For Le Chant de la Terre (Song of the Earth), Nijinska used inspiration from a folk festival and drawings by Polish artist Zofja Stryjenska.

Le Rappel (The recall) "begins in a Viennese ballroom... A young Pole is enjoying society. But the young woman he meets is Polish. She reminds him of the simpler dances of their home country."

The Concerto de Chopin "follows no plot but tries to reflect the shifting moods of the music." Baer suggested it showed Nijinska's "feeling of longing, farewell, and sorrow that she had experienced on leaving Russia" in 1921. Critic Edward Denby called it "oddly beautiful... because it is clear and classic to the eye but tense and romantic in its emotion."

Nijinska also staged La Légend de Cracovie, "a new ballet of high merit." Its story was a "medieval Polish variation of the Faust story." She used her "celebrated group architecture" but also created roles for character dance.

After Balet Polski's 1937-1938 tour, Nijinska was "abruptly released" from her position. Most likely, it was because she "insistence upon a full disclosure of the troupe's financial records." The Polish government might have been secretly moving funds. "Characteristically, Nijinska would have refused to become involved with politics or intrigue." She was replaced by Léon Wójcikowski.

Leon Woizikovsky had prominent roles in Nijinska's ballets. In 1939, he led the Ballet Polonais to the World's Fair in New York. "The company returned to Warsaw one day before the German invasion of Poland... and was never heard from again." Woizikovsky worked in the Americas during the war. He later helped reconstruct Nijinska's 1920s choreographies.

For Nijinska in 1938, the "shock of her dismissal" and "the impending war caused a profound depression."

Ballet Companies and Exemplary Ballets 1939–1950s

Nijinska and her family were in London when World War II started in September 1939. She had a contract for a new film, but it was canceled due to the war. Luckily, an offer from promoter Wassily de Basil allowed them to go to the United States. She eventually made Los Angeles her new home.

'Ballet Theatre' in New York: La Fille Mal Gardée of Dauberval

Nijinska began choreographing a "rustic and comic" two-act ballet from the 18th century, Jean Dauberval's La fille mal gardée (The ill-watched Daughter). For the first season of Ballet Theatre (now ABT), it opened in January 1940 in New York City.

La Fille Mal Gardée is perhaps "the oldest ballet in the contemporary repertory" whose "comic situations are no doubt responsible for its survival." Jean Dauberval wrote the story and first choreography. It premiered in 1789 and quickly became popular. Later versions used music by Peter Ludwig Hertel.

Dauberval's story is about a lively country romance between Lise and Colas. Lise's mother, widow Simone, wants her to marry the rich but boring Allain.

"In America, the most important production was Nijinska's for Ballet Theatre in 1940." Lucia Chase invited her to stage her own version, which included decor from Mikhail Mordkin. Nijinska revised Petipa's Russian version and staged it with Irina Baronova and Dimitri Romanoff. This 1940 staging was brought back, and later versions were created. It eventually joined the shows of the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas.

Twenty years later in London, Nijinska's former student Frederick Ashton of The Royal Ballet staged it. He rewrote the story, choreographed to Hertel's music, and provided new decor. The result was popular and "a substantial work".

Also for Ballet Theatre, in 1951 Nijinska choreographed and staged the Schumann Concerto, with music by Robert Schumann. Alicia Alonso and Igor Youskevitch were the main dancers. The romantic music frames the abstract ballet in three parts. In 1945, Nijinska choreographed Rendezvous with music by Sergei Rachmaninoff. Both were staged for Ballet Theatre in New York City.

'Hollywood Bowl': Boléro, Chopin Concerto, Etude-Bach; and Jacob's Pillow

Later in 1940, she staged three short ballets for a performance at the Hollywood Bowl. For the show with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, she chose favorites from her previous choreographies: Ravel's Boléro (revised), the Chopin Concerto (from 1937), and Etude-Bach (originally 'Holy Etudes' from 1925, revised). The event drew 22,000 people and featured dancers Maria Tallchief and Cyd Charisse.

Nijinska brought back Etude-Bach and Chopin Concerto again in 1942, at the Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival. The cast included dancers Nina Youshkevitch and Marina Svetlova.

'Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo' under Denham in New York: Snow Maiden.

Nijinska choreographed Snow Maiden in 1942 with music by Alexander Glazunov, for 'Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo'. Snow Maiden was based on Russian folklore. The maiden, the Frost King's daughter, would melt if she fell in love with a human. The choreography "did not open any new avenues of artistic exploration." But critic Edwin Denby noted that her groupings and dance phrases kept "a certain acid edge" against the sweet music.

A revised Chopin Concerto was also staged by Nijinska in 1942. The New York Times critic John Martin highly praised it. In 1943, Nijinska choreographed the Ancient Russia ballet, music by Tchaikovsky, with designs by Nathalie Gontcharova.

For Denham's company, Nijinska and George Balanchine "were well-known choreographers." However, "not Nijinska but another woman-an American-who revitalized the Ballets Russes in 1942. Agnes de Mille [did it with her] Rodeo ..."

'Ballet International' in New York: Pictures at an Exhibition

During the 1940s and 1950s, Nijinska was the ballet mistress for the International Ballet, later known as the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas. The company performed mainly in Europe until 1961.

In 1944, for an opening in New York, she choreographed Pictures at an Exhibition, a suite of piano pieces by Modest Mussorgsky. Mussorgsky wrote no ballet music, but two of his works inspired Nijinska: Night on Bald Mountain (1924) and Pictures.

Costumes and decor were by Boris Aronson. Aronson was a student of Aleksandra Ekster, Nijinska's designer in Kiev and Paris. Nijinska was the first to choreograph Pictures.

In 1952, for Marquis de Cuevas' Grand Ballet de Monte Carlo, Nijinska choreographed Rondo Capriccioso. It opened in Paris, with Rosella Hightower and George Skibine as main dancers.

Ballet Companies: Revivals of Her Early Choreographies 1960–1971

'Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas' in New York: The Sleeping Beauty

In 1960, the Cuevas Ballet produced a revised The Sleeping Beauty, which Nijinska was supposed to stage. She knew the ballet from Diaghilev's 1921 production. She had created several popular dances for it. In 1922, she and Igor Stravinsky shortened it into the successful one-act ballet Aurora's Wedding.

Nijinska began to create her revised choreography. However, a conflict arose over artistic issues. She refused to compromise and left the company. Robert Helpmann then joined the project. In the end, the Cuevas company gave choreographic credit to both, as Nijinska-Helpmann.

'The Royal Ballet' of London: Les Biches and Les noces

In 1964, Frederick Ashton of The Royal Ballet asked Nijinska to stage a revival of her ballet Les Biches (1924) at Covent Gardens. Ashton had been a choreographer for The Royal Ballet since 1935 and became its director in 1963.

Nijinska had mentored Ashton's career when he was a young student. In 1928 in Paris, she was the choreographer for Ida Rubenstein, where he danced. He performed in several of her choreographed works. Ashton saw her as a positive influence on ballet. The staging of the revived Les Biches went well. Two years later, Ashton asked her to return to London and stage her Les noces (1923) with his company.

These 1964 London productions, according to dance critic Horst Koegler, "confirmed her reputation as one of the formative choreographers of the 20th century."

Other Stagings: Brahms Variations, Le Marriage d'Aurore, Chopin Concerto

After these London events, Nijinska "was repeatedly invited to revive several of her ballets". She staged Les Biches in Rome in 1969, and in Florence and Washington in 1970. Also Les Biches, and a revised version of Chopin Concerto and Brahms Variations, for the Center Ballet of Buffalo in 1969.

Les noces was staged in 1971 in Venice. During a rehearsal, she celebrated her eightieth birthday on stage. "Between 1968 and 1972, Nijinska saw performances of Les Biches, Les noces, Brahms Variations, Le Marriage d'Aurore, and Chopin Concerto for ballet companies in the United States and in Europe."

Irina Nijinska's Further Revivals, and Others

After Bronislava's death in 1972, her daughter Irina Nijinska (1913-1991) continued her work. More performances of her mother's early ballets were staged. Several became part of current dance companies' shows.

Irina, a dancer herself, had helped her mother for many years. In the 1970s and 1980s, Irina promoted her mother's legacy. She edited and translated Early Memoirs, which was published. Irina Nijinska worked with ballet companies to help revive the choreographies. Les noces and Les Biches appeared on stage more often.

Among others, Irina brought Les noces to The Paris Opera Ballet and "Rondo Capriccioso" to the Dance Theater of Harlem. Le Train Bleu was reconstructed and staged by the Oakland Ballet. In 1981, the Dance Theatre of Harlem "produced an entire Nijinska evening". After Irina's passing in 1991, the Nijinska revivals continued.

Ballerina Nina Youshkevitch, a Nijinska dancer, revived Bolero for the Oakland Ballet in 1995. She also staged Chopin Concerto for students that same year.

Based in Los Angeles, from 1940

After World War II started in Europe in 1939, Nijinska and her family moved to New York, then to Los Angeles in 1940. "Bronislava Nijinska did not understand Americans, or they her. She was almost deaf by the time she reached the United States, and life (exile, her brother's madness, her son's death) had let her down badly."

But she continued as a ballet mistress and guest choreographer into the 1960s. In Los Angeles, she started teaching ballet in a private studio and opened her own school in 1941. Her daughter Irina Nijinska would run the school when she was away. Bronislava became a U.S. citizen in 1949.

Teaching Dance

Throughout her career, starting before her 1919 'L'Ecolé de Mouvement' in Kiev, Nijinska had taught dance. She would show ballet roles to her colleagues or new choreographies to the cast. In 1922, she started teaching at Ballets Russes, taking over from Enrico Cecchetti. Her early students included Serge Lifar in Kiev, Anton Dolin, Lydia Sokolova, Frederick Ashton, Alicia Markova, and Irina Baronova in Europe. Her auditions in the 1930s were short classes.

In 1935, choreographer Nijinska coached the young Irina Baronova for her main role as the Princess in Les Cent Baisers. Baronova was already experienced but was quickly becoming a modern classical ballerina. According to author Vicente García-Márquez, Nijinska was key to her development.

In New York, Nijinska was invited to teach in Hollywood. She opened her own ballet studio there in 1941. She often left her daughter Irina Nijinska in charge when she traveled for work. At her Hollywood studio (later in Beverly Hills), students included the prima ballerinas Maria Tallchief and Marjorie Tallchief (sisters), as well as Cyd Charisse, and later Allegra Kent.

Maria Tallchief (1925-2013) studied with Nijinska "all through my high school years". Tallchief remembered that everyone was in awe of her. "She jumped and flashed around the studio. I was under her spell." Despite "luminous green eyes," she dressed simply. Her husband translated for her. "Madame say when you sleep, sleep like a ballerina. Even on street waiting for bus, stand like a ballerina." But "Madame Nijinska rarely spoke. She didn't have to. She had incredible personal magnetism." From her, "I first learned that the dancer's soul is in the middle of the body." When Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo performed in Los Angeles, their dancers came to Madame for lessons. "And the biggest star of all, Alexandra Danilova, gave Nijinska roses when she entered the studio."

Allegra Kent (born 1937) remembered starting ballet lessons in 1949 when she was twelve. Madame Nijinska was a "nice-looking woman in black lounge pajamas with a long cigarette holder". She counted time "ras, va, tri" in Russian. "Her husband was simultaneously translating everything she said into English." Because of her powerful presence, "The world began and ended right there in that moment." After a year with her daughter Irina, Kent studied with 'Madame' herself. She learned "not to fear competing with men" and that "the light look of dance was merely the surface of a sculpture-there was a mixture of steel and quicksilver at the heart."

Work on Her Memoirs

In the last year of her life, Nijinska finished her memoirs about her early life. She had notebooks and kept theater programs. She completed a manuscript of 180,000 words. After her death in early 1972, her daughter Irina Nijinska was in charge of her writings. Irina and Jean Rawlingson edited and translated the Russian manuscript into English. The book Early Memoirs was published in 1981. These writings describe her early years traveling with her dancer parents, her brother Vaslav's development, her schooling, and her first years as a professional dancer. She also wrote about helping her brother with his choreography. During her life, she published a book and several articles on ballet.

"The full autobiographical story of her own career... is contained in another set of her memoirs, continuing from the 1914 close of [her Early Memoirs]." She also left notebooks on ballet and other writings that are still unpublished. Dance historian and critic Lynn Garafola is working on a biography of Bronislava Nijinska.

As Described by Others

Margaret Severn, a dancer, was a leading dancer in Nijinska's Paris-based company in 1931. She sometimes called Nijinska "Nij".

Lydia Sokolova, an English ballerina, performed in Ballets Russes from 1913 to 1929. Her memoirs were published in 1960.

Irina Baronova, one of the three Russian "Baby Ballerinas," worked with Nijinska in the mid-1930s. She later described the experience.

Personal and Family Life

Mother and Father

After her parents separated, Vaslav turned against his father Tomasz. Bronislava, however, remained close to her absent father, who visited sometimes. She followed his career and celebrated his successes. Her mother eventually understood Tomasz better. In 1912, her father died in Russia. Her oldest brother Stanislav died in Russia in 1918.

In 1921, Nijinska, her mother Eleanora, and her two children left Russia. It was a dangerous journey. They went to Austria to meet her brother, his wife, and children. Nijinska then rejoined Ballets Russes until 1925. After that, she worked independently. Bronislava remained close to her mother, whom she called "Mamusia". She wrote to her when away and shared her thoughts when near. She cared for her mother until she died in 1932.

Her Brother Vaslav

In her early years, Bronislava Nijinsky was greatly influenced by her older brother Vaslav Nijinsky, who was very famous. Both Vaslav and Bronislava were trained by their dancer parents from a young age. She learned from her brother's example in their childhood adventures, ballet school, and on stage. When Nijinsky started creating his first choreographies, Nijinska helped him as a dancer, following his detailed instructions. Her marriage in 1912 affected the artistic "bond between the brother and sister." But Bronislava remained loyal to her brother. She supported his career, especially during his 1914 production of Season Nijinsky in London.

In 1913, Vaslav suddenly married Romola de Pulszky in Argentina. This surprised his mother and sister. In 1917, his ballet career ended. He then lived with Romola and their children in Switzerland for many years. He died in Sussex, UK, in 1950. Vaslav was survived by his wife and their two daughters, Kyra and Tamara. In 1931, Kyra danced in her aunt Bronislava's company 'Ballets Nijinska'.

Marriages, Children

Nijinska married twice. Her first husband, Alexandre Kochetovsky, was a fellow dancer for Ballets Russes. She called him 'Sasha'. They married in London in 1912 and soon moved to Russia. She gave birth to two children: their daughter Irina Nijinska in 1913 in Saint Petersburg, and Leon Kochetovsky, their son in 1919 in Kiev. Their marriage became difficult during the war and revolution. They had always worked together in dance. After Leon was born, Bronislava and Sasha separated. He moved to Odessa. In 1921, Nijinska left Soviet Russia with her children and mother. After meeting briefly in 1921, they divorced in 1924. Their son Leon was killed in a traffic accident in 1935. Their daughter Irina, who became a ballet dancer, was seriously injured in that accident. In 1946, Irina married Gibbs S. Raetz, and they had two children. After her mother's death in 1972, she edited her Memoirs and managed revivals of her ballets. Irina died in 1991.

A love of her life, but whom she did not marry, was the famous Russian opera singer Feodor Chaliapin (1873–1938). Their paths crossed several times, but their circumstances prevented a romance. Still, their strong artistic connection and admiration continued. He remained a treasured source of her musical and theatrical inspiration.

Nijinska's second marriage in 1924 was to Nicholas Singaevsky (called 'Kolya'). He was a former student and dancer at her 'Ecole de Mouvement' in Kiev. He also left Russia. They met again as exiles in Monte Carlo. He became a dancer with Ballets Russes. They married in 1924. For four decades, he often worked in production and management, acting as her business partner. In America, he also translated for her when she taught ballet. He died in Los Angeles, California, in 1968, four years before her.

Bronislava Nijinska died on February 21, 1972, in Pacific Palisades, California, after a heart attack. She was 81. She was survived by her daughter, son-in-law, and two grandchildren.

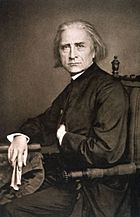

In Fine Arts

On June 11, 2011, a sculpture of Polish/Russian dancers Vaslav Nijinsky and his sister Bronislava Nijinska was unveiled at the Teatr Wielki. See the photograph at the start of this article. They are shown in their roles as Faun and Nymph from the ballet L’après-midi d’un faune. The sculpture was made in bronze by Ukrainian sculptor Giennadij Jerszow.

Images for kids

-

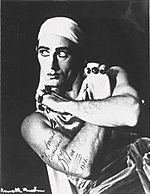

Her brother Vaslav Nijinsky

and Bronislava Nijinska,

sculpture by Giennadij Jerszow,

the Grand Theatre, Warsaw -

Enrico Cecchetti,

St. Petersburg, c.1900 -

'Ballets Russes' by August Macke, 1912

-

Nijinska in Petrouchka, Fokine's choreography. Ballets Russes, 1913

-

Choreographer Fokine in pre-war ballet costume

-

Exter's 1921 curtain design, Moscow.

-

Marius Petipa in 1887

-

The wicked fairy Carabosse by Léon Bakst, who created 300 costume designs for Diaghilev's lavish 1921 London production of The Sleeping Beauty.

-

Igor Stravinsky in Paris,

by Picasso, 1920. -

"For Les noces Natalia Goncharova initially proposed a bright, richly colored decor in the old Ballets Russes manner. Nijinska, however, would have none of it." After war and revolution, she saw in "a Russian peasant wedding: not a joyous occasion but a foreboding social ritual in which feelings were strictly contained and limited by ceremonial forms." The ballet must tell this truth and invoke such a "timeless peasant world." Goncharova "immediately took the cue and responded with earthy brown and white costumes cut to simple peasant lines, severe in their simplicity and lack of color. The sets were equally stark." Stravinsky and Diaghilev agreed.

-

Marie Laurencin (1912)

-

Playwright Molière

by Mignard (ca. 1658). -

Cast of Midsummer Night's Dream: Ross Alexander, Dick Powell,

Jean Muir and Olivia de Havilland. -

Dame Alicia Markova

-

Mussorgsky's 1881 portrait by Ilya Repin, a few days before his death

See also

In Spanish: Bronislava Nijinska para niños

In Spanish: Bronislava Nijinska para niños

- Buffalo Ballet Theater

- Category:Ballets by Bronislava Nijinska

- List of Russian ballet dancers

- Polish National Ballet

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |